Introduction

This article re-examines the history of the sect of Dādū Dayāl (1544–1603), a saint-poet of Muslim cotton-carder caste (dhuniyā) origins who lived in modern-day Rajasthan and whose discipleship grew in the heyday of the Mughal-Rajput multicultural courtly milieu. Dādū and his disciples, known as Dādū Panthīs, hold a revered place in a branch of Hindi literature we typically designate as sant (that is, associated with communities of practitioners who favour a non-imagistic approach to the religious life). In principle, the sants indulge in the formless and interior god who is identical to the Supreme Self. Yet, Dādū's disciples did not constitute a typical sant-bhakti movement with monastic followers found only in small towns, among the lower classes and common folk; rather they participated in the urban intellectual and literary cultures of courtly places like Banaras, Fatehpur-Sikri, Amber, and Marwar. With their networks in such places, Dādū Panthī religious professionals interacted with scholars, poets, and administrators of different religious commitments and caste backgrounds as they aspired to form an influential community in the diverse yet competitive religious landscape of seventeenth-century North India. The Mughal emperor's patronage of the holy men and the works of intellectuals of various faiths and knowledge systems inspired their hagiographies. They also engaged in Vedānta discussions that were prominent among Brahman intellectual and courtly circles of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Furthermore, the Dādū Panthīs partook in the growing literary culture of ornate ‘Hindi’ that emerged in the Rajput Mansabdārī settings of Mughal imperial ranking. As such, this development was influenced by the new culture of literary, religious, and philosophical exchange encouraged by the Mughal policy of sulh-i kull or ‘peace with all’ religions. Thus religious communities such as the Dādū Panth should not be understood as having only operated within bhakti circles; rather, they were also shaped by their interactions with the intellectual and literary cultures connected with new centres of imperial and sub-imperial powers in early modern North India.

The article is divided into six sections. The first three show that the Dādū Panth was part of a major shift in the history of the sant-bhakti tradition. This change is demonstrated in two ways. First, the Dādū Panth's identity was formed through engagement with the new Mughal-Rajput imperial model. Second, it participated in the discourses of this new model, which was marked by the concept of sulh-i kull. The last three sections show that the Dādū Panthīs flourished in the Marwar kingdom, where they built networks with the local Rajput royal polity and other influential castes of bardic heritage, such as the Cāraṇs. The Dādū Panthīs shared with the regional courts an interest in aestheticized Hindi literature, and this, as well as their training in Banaras and expertise on Vedānta, contributed to their establishment as a culturally important religious community in the region.

Mughal-Rajput imperial paradigm and the sants

The political alliances between the Mughals and the Hindu Rajput kings of Rajasthan, which began in the age of the emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), developed a patronage network conducive to the flourishing of major centres of Vaiṣṇava bhakti in North India. Akbar's imperial self-fashioning as saintly and divine in the 1580s resonated with the ideology of devotion to the Hindu god Viṣṇu and his incarnations Rāma and Kṛṣṇa. For the Rajput kings in the growing Mughal imperium, patronizing new Vaiṣṇava bhakti institutions was a way to assert their rising royal status in the new imperial paradigm and a means to cultivate relations with a growing bhakti ‘public’.Footnote 2 This developing patronage network and the ‘new world’ under Akbar witnessed both the merging of the Sanskrit and Persianate cosmopolis and an explosion of vernacular Hindavi (Bhāṣā/Bhākhā) manuscript production and circulation. These late sixteenth-century developments under Akbar, which continued into the seventeenth century, underpinned the abundance of bhakti literature in North India and enhanced the prestige of the more classically oriented Brajbhāṣā poetry in court settings.Footnote 3

Although current historiography demonstrates that the overall historical framework of the Mughal and Rajput alliances were supportive of the growth of bhakti communities (and particularly Vaiṣṇava bhakti communities), little scholarly attention has been given to the question of how the traditions of North Indian sants responded to the imperial dispensation. The sants were the holy men who were not Vaiṣṇava in the strict sense, since they were devoted to the formless and all-pervading godhead (nirguṇ brahma) rather than to an anthropomorphic deity. In Hindi-language scholarship, the bhakti traditions are often presented as hostile to the Mughal-Rajput ‘feudal culture’, and the sants, in particular, as only supporting the concerns of the subaltern masses.Footnote 4 Even in recent studies, sants like Kabīr (fifteenth century) and many others have been largely depicted as active in the realm of the ‘folk’ or public (lok) sphere, while reluctant to engage in courtly affairs.Footnote 5 Yet, as will be discussed, this so-called ‘feudal-culture’ was not really antagonistic to the ‘public sphere’ of bhakti. Sant movements like the Dādū Panth, which had a wider social base in Rajput, merchant, and landholding pastoral castes, imagined themselves precisely within the new Mughal-Rajput imperial paradigm and modelled their tradition on similar ideals by participating in the literary and intellectual cultures of the time.

Some of the large studies as well as essays in volumes such as the Idea of Rajasthan have explored the first two centuries of the Dādū Panth's existence—the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—within two frameworks.Footnote 6 They discuss how the community was scattered across several places in the seventeenth century, with each group making their own sense of what it meant to be a follower of the guru, Dādū. During the seventeenth century, the Dādū Panthīs saw themselves as being devoted to the formless divine, and hence linked with other prominent sant figures like Nāmdev, Guru Nānak, and Kabīr, or with the Nāth-Yogī tradition, which had long been prominent in North India. The Dādū Panth is naturally grouped with the Kabīr Panth (‘Kabīr's path’), assuming that it has the same ‘non-caste Hinduism’ character with ‘an ideological content that is in direct opposition to basic socio-religious values characteristic of caste Hinduism’.Footnote 7 These studies observe that the devotional message of inclusivity in terms of caste and Hindu-Turk affiliations, so prominent in Dādū's compositions and apparent in the wider social backgrounds of Dādū's disciples, was changing towards the end of the seventeenth century. The eighteenth century saw the formal organization of the Dādū Panth's branch of warrior ascetic (nāgā sādhus), whose membership was dominated by Rajputs and which developed close affinities with the Jaipur state.

Monika Horstmann's sustained engagement with the Dādū Panth, including its history, devotional practices, manuscript culture, and networks in eastern Rajasthan, has brought a nuanced understanding of the tradition.Footnote 8 In contrast with previous studies, Horstmann demonstrates that the nāgā branch was already developing in the second half of the seventeenth century. During this time, the Dādū Panthī nāgās were not fully armed, but they cultivated a taste for high literature that was often modelled on the literary innovations happening at the Amber (Amer/Jaipur) court. This is made evident by Rāghavdās, the celebrated author of the Bhaktamāl (1660), who hailed from a nāgā background.Footnote 9 Rāghavdās composed his hagiography in the quatrain (kavitt-savaiyā) style that was more popular among the courtly Brajbhāṣā poets of the time. Additionally, Horstmann demonstrates that from the late sixteenth century, the Dādū Panthīs developed networks with local ruling elites in the Amber area and cultivated a sophisticated tradition of homiletics centred on Dādū's poetry as well as that of other sants like Kabīr. Recently, the community has received extensive scholarly attention for its vernacular treatises on theology, metaphysics, and liturgy, and for its construction of support networks with the merchant castes in Rajasthan.Footnote 10 From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, the Dādū Panthīs produced major works of Advaita Vedānta (non-dualist thought) in the vernacular. These were prominent enough to receive high praise from the nineteenth-century reformer and monk Svami Vivekananda.Footnote 11

Engaging with the growing scholarship on the Dādū Panth, I demonstrate how the new Mughal-Rajput imperial paradigm, which generated the idea of sulh-i kull (peace with all or universal civility), became a new way for Dādū's disciples to make claims to high status among other religious communities within their ambit. For instance, Dādū's hagiography, the Dādū janma līlā paracī (DJLP, or The Divine Acts of Dādū),Footnote 12 which was written by his Fatehpur Sikri-based merchant disciple Jangopāl in circa 1610–20, evinces a competitive tone towards the Jains, who engaged with and received high imperial honours from Akbar and Jahangir. The hagiography draws on networks similar to those of the Jain monks who were brought to the Mughal court by Jain ministers. The Dādū Panthīs presented the Rajput king of Amber as being instrumental in bringing Dādū to the Mughal capital for discussions with Akbar.Footnote 13 The idea of self-realization (ātam khabar) and the equality of all humans (sab jīvani suṃ samitā) are specifically highlighted in those discussions in the shorter recensions of the hagiography's manuscript. Highlighting the characteristics of Dādū's teachings as being beyond religious and caste boundaries, and against Brahman supremacy also ran parallel to Jain thought. In the larger recensions of Dādū's hagiography, the result of these discussions was precisely connected with Akbar's proclamations (hadīs, Hadith) that the slaughter of all animals should be banned. The Dādū Panthīs did indeed give credit to Dādū himself for such laws that honoured the Jain monks and community. Nonetheless, such hagiographic imaginations mark a new imperial paradigm at work that provides equal protections for all religions.

Drawing on the Sufi idea of cillā (from Persian cihil, 40 days of contemplation and austerities), the hagiography states that Dādū's interactions with Akbar and Mughal intellectuals like Abu'l Fazl lasted 40 days, and presents Dādū as the master, a pīr of both Hindu and Turks.Footnote 14 In much the same way that the Andalusian mystic Ibn ‘Arabi's (d. 1240) non-dualistic thought was politicized in the Mughal sulh-i kull, Dādū's hagiography politicizes sant-devotional ideas for ideal kingship.Footnote 15 It bestows Akbar with the same spiritual epithets that were common for great sants like Kabīr. The Dādū Panthī attributes are in keeping with the sulh-i kull paradigm in which Akbar was considered the ‘saint of the age’, demonstrating that spiritual ability and intellectual discernment are linked with kingship and thus politicized as a hallmark of sovereignty.

Jangopāl was an early disciple of Dādū who clearly applied the ideals of Advaita Vedānta to sant devotion and whose works became popular in Agra-based Jain intellectual circles—confirming the existence of interactions between Dādū Panthīs and Jains. This was, however, only the beginning of a long history of profound Dādū Panthī engagements with Vedānta. Dādū's prime disciples, like the Banaras-trained Sundardās (1596–1689), made non-dualist thought a primary intellectual position of sant devotion. Similar to Dādū Panthīs’ earlier associations with the Mughal imperial paradigm, it is Sundardās and his fellow Dādū Panthīs’ profound engagements with Vedānta and aestheticized Brajbhāṣā poetry that solidifies their relationship to the Rajput kings. This was the case, for example, with Marwar's Jaswant Singh (r. 1638–1678), who politicized Vedānta with the notion of ideal kingship in his Brajbhāṣā works. The Marwar kingdom's patronage of Dādū Panthī individuals remained strong until the late nineteenth century, a fact corroborated by land grants and hagiography. With such a significant Dādū Panthī presence in Marwar, the widely circulating bhakti poetry takes a regionally specific form: it is now presented in Marwari language (later called Rajasthani) and incorporates the specific poetic style that was cultivated by local bardic poets. Teaching and composing works on non-dualistic thought, however, remained current among the Dādū Panth until the nineteenth century. In the later period, the Dādū Panth's networks grew among the Rajput courts of not only Rajasthan but also of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh to such an extent that they were able to train major court poets of bardic heritage.

The hagiography of Dādū in context

Dādū's hagiography registers the changes in sant-tradition that were occurring in the Mughal-Rajput imperial milieu. Heidi Pauwels has helpfully laid out some methodological aspects for reading hagiography, a genre that became central to the formation of religious communities in the early modern era.Footnote 16 At first glance, the hagiographies contain generic topoi such as stories and conflicts between asceticism and worldly responsibilities, orthodoxy and bhakti, spiritual and mundane power, and so on. However, upon closer inspection, these topoi consist of complex layers of meaning and processes which can only be explored by situating the poems in the composer's context and investigating why certain aspects of the poem are elaborated upon, explained, or changed in the later circulation of a hagiography. Most importantly, Pauwels writes, it is necessary to read how the lives of holy men are perceived and how the devotional communities are ‘imagined’ in the image of the holy man, whose ideals the community want to emulate and record in such texts.Footnote 17

Dādū's hagiography is composed in Marwari-influenced Brajbhāṣā, and it narrates the sant's life from birth to death.Footnote 18 The poem says that Dādū was born in Ahmedabad in 1544 (vs 1601) in the house of a cotton carder. He arrived in Sambhar (Rajasthan) in 1573 (vs 1630) where his son Garībdās was born in 1575 (vs 1632). A few years later, he went to live in Amber, where he spent almost 14 years during the late sixteenth century.Footnote 19 During his stay in Amber, Dādū is said to have met with Akbar in Fatehpur Sikri in 1585 (vs 1642). His interactions with Akbar, his courtiers, and the Amber ruler are expanded in the larger manuscript versions of the hagiography but are nonetheless presented in great detail in the shorter versions as well, both of which start a year apart.Footnote 20 According to the hagiography, Dādū left Amber a few years after his meeting with Akbar and for the next ten years he travelled to various places such as Kalyanpur in 1593 (vs 1650) and to Sambhar once again. Dādū arrived in Naraina in 1602 (vs 1659), where in the following year he died on a nearby hill. After that Naraina became an important centre for the Dādū Panthīs.

Jangopāl's hagiography is surprising for the readers of bhakti hagiographies due to the emphasis it puts on dating the events of Dādū's life. In this regard, the mid-seventeenth-century Sikh janam-sākhīs (hagiographies of Guru Nanak) are somewhat closer to Jangopāl as they note Nānak's dates of birth and death.Footnote 21 This alludes to a parallel process at the Mughal court whereby the imperial reign of Akbar was chronicled and the composition of genealogies was gaining strength. The Rajputs took part in these practices with great fervour a little later in the seventeenth century.Footnote 22 It is not clear in the hagiography why Dādū went to live near Amber; there is only a statement that he found the area a potent location to practise devotion, thereby evidencing Amber's growing importance in patronizing bhakti sects.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, Amber's ties with the Mughals form the base through which Dādū's visit to the Mughal court is portrayed in Jangopal's hagiography. Just as Emperor Akbar exemplifies how discussions and debates on faiths (dīn kī goṣṭhī) bring together kings and holy men, a large portion of Dādū's hagiography roots itself in this developing political milieu.

Scholars agree that Jangopāl composed Dādū's hagiography somewhere between 1610 and 1620 ce.Footnote 24 Its last two chapters concentrate heavily on establishing and celebrating the authority of the next abbot of the sect—Dādū's son and disciple Garībdās (d. 1636).Footnote 25 There are instances of tension between Garībdās and Rajab, the foremost sant of the sect after Dādū.Footnote 26 This tension is obliquely reflected in the verse with which this article starts, in which Rajab is portrayed as the foremost disciple of Dādū, from a song written later than Jangopāl's hagiography and by a disciple of Rajab. These instances of tension between Dādū's prominent disciples might have propelled Jangopāl to strongly support Garībdās's position in order to encourage Dādū's followers to be a unified community. The hagiography makes it clear not only that ‘all sants’ made Garībdās the rightful heir to the community during a grand festival but also that Dādū actually spoke with Garībdās on the matter of whether the latter should lead the community further.Footnote 27 Such transmission of authority and divine truth from Guru to a worthy disciple—not merely monetary support or patronage—is essential to the formation of a religious community, and Pauwels has superbly studied a reverse case of such a phenomenon which illuminates the mechanics of such transitions.Footnote 28 Besides establishing Garībdās's authority, the hagiography institutes the geography of the Dādū Panthī community by mapping out the wanderings (rāmat) of Dādū. It notes towns and villages in the areas of Sambhar-Shekhawati, Amber, and Marwar, relating them to Dādū's visits. Jangopāl names Dādū's various adherents: people from royal to pastoral communities, Rajputs and Pathans to merchant followers, men as well as women, and his mighty disciples to lay followers.Footnote 29

Five chapters of the hagiography are devoted to Dādū's meeting with Akbar. This is the largest hagiographical account of the imagined event, as other disciples of Dādū also mention it in their poetry.Footnote 30 The grand portrayal of the episode known as ‘Dādū meets Akbar’ can be understood as Jangopāl competing with the Jain communities of the time, one of the few groups to receive high honours from both Akbar and his successor Jahangir (r. 1605–27). Most communities are neither mentioned in Mughal courtly literature nor given the importance accorded to them in their own written traditions. The Brahmans’ attempt, in a bid to curry imperial favour, to get the Jains of the Tapa Gaccha branch prosecuted at court in the early 1590s for ‘atheism’ is a significant example of such competition for imperial patronage.Footnote 31 There might have been, however, some events close in time to the composition of Dādū's hagiography which inspired Jangopāl to allude to the Jains. Rajiv Kinra notes that in 1610, ‘Jahangir prohibited the slaughter of all animals throughout the Mughal dominion for 12 days out of deference to the Jain community in Agra, who were observing a sacred fast—a proclamation commemorated in two vivid paintings by the artist Ustad Salivahana.’Footnote 32 Jangopāl, who was living in Fatehpur Sikri, must have been aware of these events. Significantly, Jahangir had already made donations in 1605 to the Dādū Panthī centre in Naraina in the form of a well and two residential buildings, as an inscriptional record preserved at the centre shows.Footnote 33 On his way to Ajmer, Jahangir's stop at Naraina and his meeting with Garībdās are depicted in vivid terms by Rāghavdās's later Bhaktamāl (1660 ce). Jangopāl, however, ‘imagines’ such imperial favours from Jahangir to have occurred earlier at the will of Akbar and in the more prestigious Mughal court itself.

The later hagiographer Rāghavdās adds a new aspect to this meeting between Dādū and Akbar. He mentions that Dādū revealed the throne of light (tejmaya takhat) to Akbar during the same meeting. The commentator on Rāghavdās's hagiography, Caturdās (fl. 1800), calls it the hidden throne (ghaibī takhat).Footnote 34 This might refer to the divine throne mentioned in the Quranic ‘ayat al-Kursi’ (the throne verse).Footnote 35 It could also refer to the well-known miracle in which the Prophet Muhammad goes on his ascension journey (mi'raj). He is the only one who can reach the final stage of the ‘arsh (‘throne’) and witness Allah sitting on his throne. This would imply that Dādū had the same ability as Muhammad or any accomplished saint. Therefore, the ‘Dādū-meets-Akbar’ legend was growing ever larger within Dādū Panthī circles. As new identities emerged in the community, such as the warrior ascetic branch from which Rāghavdās hailed, such imagined interactions gave Dādū's disciples a sense of the mystical power and authority of their guru.

Hagiographic display of a Mughal goṣṭhī

In 1679, the Maratha king Shivaji Bhonsle (r. 1674–1680) reportedly wrote a persuasive and poetic letter to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir (r. 1659–1707), requesting him to rescind the poll tax on non-Muslims (jaziyā) that had been implemented in the same year.Footnote 36 The Mughal monarch is reminded of the policy of ‘universal peace’ (sulh-i kull) in the letter, which was developed under the reign of his great grandfather, emperor Akbar.Footnote 37 What concerns us here is the following section of Shivaji's letter which mentions several sects that benefited from this policy:

That architect of the fabric of empire, [Jalaluddin] Akbar Padishah, reigned with full power for 52 [lunar] years. He adopted the admirable policy of perfect harmony (sulh-i kull) in relation to all the various sects, such as Christians, Jews, Muslims, Dadu's followers, sky-worshippers (falakia), malakias, materialists (ansaria), atheists (daharia), Brahman and Jain priests. The aim of his liberal heart was to cherish and protect all the people. So, he became famous under the title of ‘the World's spiritual Guide’ (Jagat Guru).Footnote 38

Among the several religious communities and sects mentioned, the reference to Dādū and his disciples is particularly significant, since they are the only new community in Akbar's era that are clearly named with reference to their founder. Dādū's initial followership undoubtedly grew during Akbar's reign. While other communities, such as the Jains, received attention in Akbar's court histories, no such contemporary accounts exist for Dādū or his followers.Footnote 39 The opinion in the letter attributed to Shivaji, however, is very much in line with outsider perceptions of the Dādū Panth. The bhakti sants of Shivaji's own Maratha region give one of the earliest testimonies of Dādū's social background—his dhuniyā/pinjārā (cotton-carder) origin—as his caste was later Brahmanized in the sect.Footnote 40 Also, the famous encyclopedia of religions written in Persian by the Azar Kayvanis, Dabistān-i Mazāhīb (School of Religions, circa 1650), notes several of the Dādū Panth's non-conformist practices.Footnote 41 It calls Dādū a dervish (charismatic holy man, often a Muslim Sufi) and mentions his origin as a cotton-carder.Footnote 42 While there are possibly no existing historical records of Akbar's favour to Dādū's followers, the sulh-i kull paradigm and the spirit of religious innovation, accommodation, and renewal it generated are precisely that which inspires the Dādū Panthī hagiography.

Azfar Moin demonstrates that ‘Total Peace’ (sulh-i kull) ‘was a radically accommodative stance for its day, especially when compared to the intolerant manner in which other Muslim and Christian polities of the early modern world dealt with religious difference’.Footnote 43 He persuasively argues that the paradigm was meant to solve a long-standing problem created by the monotheistic ban on oaths sworn on non-biblical deities. Such a ban restricted the ability of Muslim kings to ‘solemnize peace treaties with their non-monotheist rivals and subjects’.Footnote 44 By explicitly and unapologetically overturning this ban and declaring an age of religious freedom, Akbar unleashed new imperial rationalities that inspired a host of inter-religious engagement, the rethinking of religious identities, and the emergence of new religious movements. Other Mughal emperors continued Akbar's open-minded policy towards managing religious difference in the seventeenth century because it had, in Rajiv Kinra's words, ‘the balance and compromise necessary to maintain the stability and peaceableness of the social order within a ruler's dominion’.Footnote 45

This bold new policy of the Mughals resonated with emerging religious communities such as the Dādū Panth. Hints of the new Mughal imperial rationality and religion-making impulse entered their hagiographical discourses. The most noteworthy aspect of this imperial rationality is the idea of discussion and debate itself: the goṣṭhī of Dādū with Akbar and his courtly intellectuals and noblemen for 40 days. These discussions are based in an exchange of ideas and significantly tend to avoid miracles—a ubiquitous feature of the genre. More important than miracles is the fact that Dādū is presented to Akbar and his courtly elites as ‘Kabīr embodied’—as possessing the jñāna (gnosis) of Kabīr.Footnote 46 In other words, Akbar wanted to speak with Dādū because he had heard that the latter was the true embodiment of Kabīr. Indeed, presenting Dādū as such was not Jangopāl's innovation. The fifteenth-century sant Kabīr is, apart from Dādū himself, the most important figure for the Dādū Panthī community. Kabīr's poetry is thoroughly preserved in Dādū Panthī anthologies and evidently Dādū himself remembered Kabīr as the one who established the ideals of nirguṇ bhakti. Jangopāl, however, shows members of the Mughal court, including Akbar, talking about Kabīr and seeing his image in Dādū:

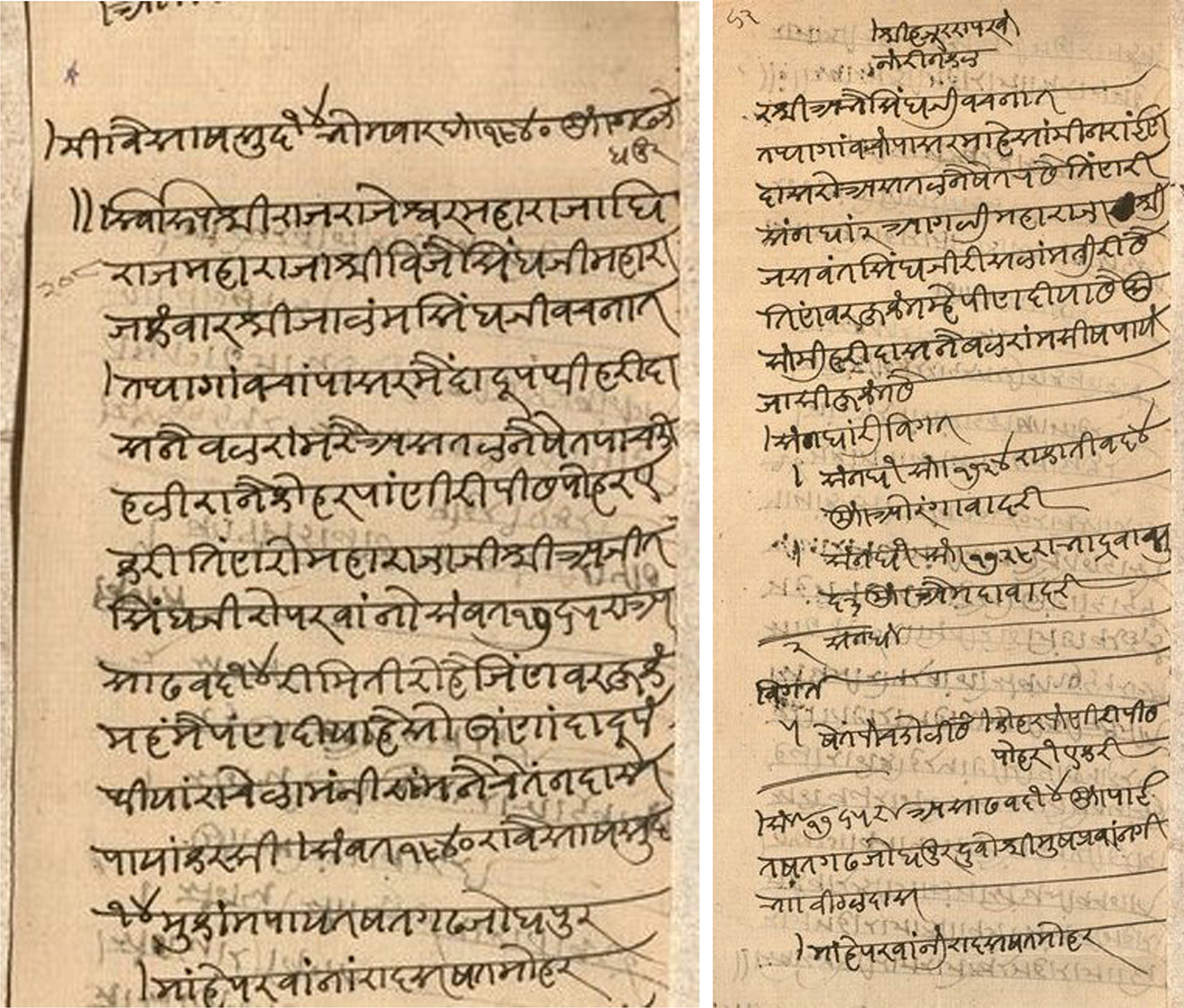

![]()

Then [Akbar] told king Bhagvantdās, ‘your lord is the joy-giver to all,

I have heard the glory of his name in many ways, as if Kabīr is residing in him’.Footnote 47

It appears from such descriptions as if Jangopāl was aware of the popularity of Kabīr in Mughal courtly circles. Akbar's main intellectual, Abu'l Fazl, remembers Kabīr as ‘the assertor of the unity of god’, a muwāhid, in his Persian accounts.Footnote 48 The muwāhid idea is used by Abu'l Fazl to refer to followers of Ibn ‘Arabi's doctrine of wahdat al-wujud (the Unity of Existence). In other words, these are the categories into which the Dādū Panthīs may be assimilated. By the time of Akbar's reign, several traditions, such as the Vaiṣṇavas in Vrindavan, the Rāmānandīs, the courtly anthology traditions of Jaipur, Sikhs, as well the Dādū Panthīs, were remembering Kabīr and giving him an important position in their textual traditions. There may be several reasons why Kabīr was known in Mughal courtly circles, but Jangopāl constructed his account to suggest that it was Kabīr's popularity that brought Dādū to Fatehpur Sikri. It is then Dādū who conveyed Kabīr's poetry to the Mughal court. In order to do so, Jangopāl imaginatively moved Dādū from Amber to Fatehpur Sikri.

The philosophical discussions of holy men with courtly elites was not a readily available model for Jangopāl to draw from, at least not in the Indic-language hagiographical tradition. Devotional poets and figures are said to have avoided courts and courtly affairs, as reflected in both devotional hagiography and the Chishti Sufi tradition.Footnote 49 But as we will see in the next section, the reality of land grants demonstrates that this model had it limits. Jangopāl indeed evinces some of this earlier ambivalence about the court, but he adopts new strategies in order to make the meeting happen. His model was actually Akbar's discussions with individuals representing various religious traditions reported to have occurred at the Ibādat Khānā. Jangopāl calls such conversations ‘discussions on faiths’ (dīn kī goṣṭhī), and they happened in Fatehpur Sikri earlier than the hagiography places them. A somewhat earlier idea, displayed elaborately in the hagiography of Kabīr composed by the Rāmānandī Anantdās around circa 1600, is that the power of bhakti (bhagati pratāp) makes the sants superior to worldly rulers.Footnote 50 The sants also perform miracles (karāmāt) which exhibit their divine power. In Kabīr's hagiography, fierce contestations are depicted between him and the current rulers. The Delhi sultan Sikandar Lodi is often referred to as demonic (asura), and other ruling elites are mostly rejected by Kabīr.Footnote 51 The rulers only accept Kabīr as a great saint after he shows his divine might. Such contestations are not entirely absent in the hagiography, but during Dādū's interactions with the Mughal emperor and Rajput kings, discussions and debates take the place of such miracles.

The hagiography also exhibits a tension fundamental to such discussions. On the one hand, Dādū reformulates Kabīr's ideals as being totally dependent on an orientation towards the divine, a renunciation of wealth, and a rejection of the favour of worldly authority. Yet, on the other hand, the newly arising political formations and opportunities for patronage in Mughal-Rajput settings lead Jangopāl to portray Dādū following the orders of the worldly rulers. The situation arises when Dādū simply rejects Akbar's notifications (parwānā) to go to Fatehpur Sikri:

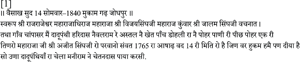

![]()

Emperor Akbar heard about him and sent summons day and night.

Akbar lamented that if Swami (Dādū) wouldn't come then he [Akbar] wouldn't be happy.

Dādū's repeated rejections of Akbar's invitation posed an even bigger challenge to Akbar's mansabdar (rank-holder) and Amber's Rajput king Bhagwant Dās (r. 1574–89).Footnote 52 The king promises Akbar that he will bring the sant, who resides in his political territory, to the Mughal court, or else he will face the emperor's wrath. The pressure increases further upon Dādū too when he receives a letter from king Bhagwant Dās. Dādū finds himself in a dilemma. He is apprehensive that the king may force him to go to the Mughal court.Footnote 53 The hagiography therefore adopts a strategy to resolve such dilemmas and contestations, which brings the sants and the kings into an amicable relationship. Unlike the life narratives of previous sants, in Dādū's hagiography, the God (Hari/Ram) plays the role of an intermediary. With Dādū facing such pressure from the king, it is Ram, dwelling within him, who appears in Dādū's meditation and permits him to visit the emperor:

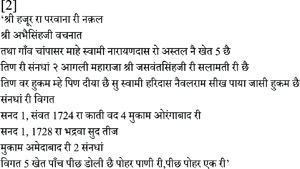

![]()

The lord (Dādū) left it to Ram, who indicated in [Dādū's] meditation his call to go!

There is, in essence, a new religious worldview at work here, one in which saints are being redirected to engage with the world rather than renounce it. While resolving the initial dilemma of bringing Dādū to the Mughal court, the hagiography finds occasion to place sant poetry in courtly contexts by highlighting Dādū's interactions with other religious scholars (paṇḍits and shaikhs) and courtly intellectuals. The popular sant genre of couplets (sākhī) becomes the medium through which Dādū engages in such discussions. Themes like ‘the greatness of reciting the name’ (nām pratāp/mahimā), the ‘formless god’ (nirguṇ Rām), and ‘allegiance to the inner dwelling supreme’ (ghāṭ maiṁ niranjan), contentment (santoṣa), controlling the senses, and so on emerge in the discussions led by Dādū. Before such discussions happened, however, Akbar and his courtly intellectuals Abu'l Fazl and Bīrbal closely examined Dādū.Footnote 54 The way in which the court assembly's first discussion on the question of the inner-dwelling and ‘abstract’ supreme self (iṣṭa) is portrayed has a parallel on the Mughal side with sulh-i kull, an abstraction of the supreme truth. Jangopāl makes Dādū explain the meaning of several names for the Creator which were popular in Hinduism and Islam, among them Rām, Alah/Alakh, Rahīm, Gopāl, or Sirjanhār. This was done to reach a higher level of abstraction in which the truth of diverse religious traditions becomes translatable across different faiths. The hagiography also brings forth a performative aspect of sant poetry to the Persophone audience. The contextual performative space makes Dādū's language Persianized with a Sufi tone. Responding to Akbar's call of describing the ‘state of being/mind’, Dādū recites:

![]()

Dādū says one should remain intoxicated in passion and one's heart should yearn for the vision of the beloved.

Every moment one should remain absorbed in the presence of god, and be mindful and alert.Footnote 55

At the end of the discussions Akbar offers Dādū villages and wealth. The guru rejects the offer, contextualizing his response within themes of bhakti poetry further along in the narrative. Here Jangopāl has Dādū recite Kabīr's verses which proclaim some of the prime philosophical positions of the sants, such as ‘total allegiance to the one and only lord’ (pativrat) and ‘poverty as spiritual strength’ (dīn gharībī laghutā). Akbar recognizes Dādū as a master of both Hindus and Turks. Here, when the discussions ends, Akbar is described with an important attribute that was previously reserved for sants, namely having ‘the power of discernment or verification’ or ‘the consciousness of oneness/equanimity’ (bamek or bamek samitā). Kabīr is described as having this power in his hagiography.Footnote 56 Dādū's hagiography confers upon Akbar the same virtue of being discriminating (bamekī/vivekī):

![]()

Emperor Akbar is very discriminating, [he] has examined good and evil with truth.

By bestowing upon Akbar the attribute of discernment, Jangopāl brings the sant-bhakti ideals to the political realm. Here spiritual ability and intellectual discernment are equated and politicized. A similar process had already taken place in the extensive writing of Abu'l Fazl who, in his preface to the Persian translation of the Mahabharata, politicized Ibn ‘Arabi's mystical method of tahqiq (‘realization’ or ‘verification’ of divine truth)—a key Neo-Platonic principle behind sulh-i kull—for managing religious difference.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, the hagiography implies that Akbar obtained his discerning qualities and discriminating nature only after hearing the poetry of Kabīr and engaging in conversation with Dādū. Jangopāl completely abstains from showing any kind of miracle, but the divine glory of Dādū lies in him, satisfying the elite audience with his answers to their questions and in his apt presentation of sant poetry and philosophy in courtly contexts. This is a key shift that conforms to the new culture of rational debate among religions at the court. Only through such discussions did Akbar recognize that Dādū was not just an ordinary cotton-carder wandering on the streets of Fatehpur Sikri but a true holy man. He says, according to the hagiography:

![]()

If you have not found the lord, then for what reason have I called you here?

Many cotton-carders (pinjārās) keep wandering in the city of Sikri doing hard labor.

While Akbar is described as the man with discerning qualities (vivekī), the Amber king too is portrayed as a benefactor of the sants. It is the Amber king Bhagwantdās who first greets Dādū in Fatehpur Sikri, serves him at his residence, and arranges his meetings with several others.Footnote 58 The hagiography demonstrates that in addition to bringing the sants to the Mughal court, these Rajput kings also established the holy man in their own region's public as well. This developing scenario is given great importance in the hagiography:

![]()

And if the king establishes the honor of Dādū,

Then all naturally become Dādū's followers.

While kings are described as supporting the sants in this new historical context, the idea that kings are, and should be, discriminating (bamekī/vivekī) is further emphasized. During the latter part of Dādū's stay in Amber, religious authorities complained to the then king Man Singh (r. 1589–1614) about Dādū's rejection of caste norms and religious boundaries, his opposition to child marriage, his censure of the hardships and taboos imposed on Hindu child widows, and his support for celibacy.Footnote 59 Some of these descriptions are classic topoi of hagiography but the way in which the age of marriage is so specifically discussed and child marriage is contested by Dādū again resonates with Akbar's censure of child marriages in his ordinances regarding the same issue in 1585–86.Footnote 60 The hagiography notes that the Brahmans and Baniyās (merchants) of Amber were angry, and the king acted upon their complaints. Yet Man Singh faces the dilemma that any action taken against the saint could cause Dādū to leave Amber. Dādū does leave Amber, but through Jangopāl's strategy, he departs from the king's domain rather amicably.Footnote 61 This episode may be interpreted as Dādū falling out of the Jaipur king's favour after living there for 14 years, and Jangopāl's description could be a form of ‘damage control’ in which the Dādū Panthī community sought new ties with the Amber king.

This hagiographical narration of Dādū's encounters with Mughal-Rajput courtly patronage closely resembles the literature that emerged in similar political settings. The way in which the Dādū Panthīs describe local kings forming networks to bring holy men to the Mughal court, as well as supporting them in their respective regions, bears striking similarities to how the Jains described such events. Amber's king convinces Dādū to meet Akbar in Fatehpur Sikri, and the Jain minister Karmacandra Bacchāwat of Bikaner is the facilitator in bringing Jinacandra Sūri from Khambhat (Cambay) to Lahore in 1591. The Jain side of the episode is described in short hagiographical poems in Gujarati and Brajbhāṣā by the Jain monk and polyglot Samaysundar (1563–1646), a śvetābmar Jain monk-intellectual with multilingual talents from the Kharatara Gaccha branch who was active in Rajasthan and Gujarat. Samaysundar was also one of the monks who accompanied Jinacandra Sūri on their journey to meet Akbar in Lahore. In his accounts, the Jain minister Karmacandra Bacchāwat assumes the same role that Bhagwantdās is portrayed to have played for Dādū:

One day Akbar says to the minister Karmachandra,

‘I have heard about your Guru in Gujarat, an expert man with endless grandeur.

Invite him soon with an edict, giving him enormous reverence and respect.’

Jain sources broadly depict the monks conversing with Abu'l Fazl in the manner we have noted in Dādū's hagiography above.Footnote 63 Both traditions praise Akbar for his ability to recognize true holy men. The Jain monk Samaysundar extols the emperor for the gesture of honouring the Jain monk Jinacandra Sūri.Footnote 64 Dādū Panthīs shared a common habitus with the Jains, and these similarities show how the Dādū Panthīs were aware of the activities of the Jain monks at the Mughal court. Dādū had a strong merchant following that put this sect in conversation with the Jain tradition. Take, for example, Samaysundar's description of the Jain congregation that stopped at the town of Didvana in Rajasthan on their way to Lahore to meet Akbar.

![]()

He bowed to Shri Śāntināth, the guru placed hand on head, Samaysundar accompanied, set off in grandeur.

Gradually [we] moved, Sirohi was pleasant, the Sultan was pleased, seeing [Jinacandra] in front of him.

Around Jalore, his arrival was revealed, he conquered the opponents in Didvana, and obtained victory.Footnote 65

Didvana was the primary town from which Dādū's merchant followers originated. Samaysundar describes Didvana as a place of debates and discussions (dinḍvāṇai jīte bhaṭ).Footnote 66 It was actually a few years after this Jain congregation passed through the town that Dādū visited Didvana on the invitation of his merchant disciples.Footnote 67 This suggests the awareness of Dādū Panthīs, and possibly Jangopāl, of the Jain's activities at the Mughal court, some of which might have inspired him to present his own tradition—in competition with the Jains—as one honoured by the same highest authority.

With these similarities being noted, there are differences between the Jain hagiographical poems and Dādū's hagiography, which lie in their acceptance of elite patronage. Dādū's hagiography still presents a tension with accepting royal favours. By contrast, the Jain literature in Gujarati, Marwari, and early Hindi thoroughly celebrates the edicts received from the Mughal emperor on behalf of the Jain monks. The Jain minister Karmacandra Bacchāwat is remembered for his magnificent display of wealth in celebrating the success of Jain monks in the Mughal court.Footnote 68 The disregard for royal favour prevalent in North Indian sant hagiographies is still present in the hagiography of Dādū. Additionally, in the context of Akbar's favouring of diverse religious communities, the Dādū Panthīs’ competition with the Jains, who evidently received high royal honours, cannot be ignored as a possible motivation for the hagiography.Footnote 69 Declaring that Dādū was honoured by Akbar and his intellectuals, Jangopāl's work implies that elite circles viewed the sant tradition as desirable; by building the whole account on Kabīr’ legends and poems, the hagiography aspires to bridge elite and popular cultural arenas.

Networks of Banaras-trained Dādū Panthīs in Marwar

Rāghavdās's Bhaktamāl, which comes later than Jangopāl, highlights a different phenomenon that was nonetheless related to the sulh-i kull paradigm: the Dādū Panthīs’ strong engagement with Vedānta and non-dualist thought. The hagiography mentions 52 disciples of Dādū but only describes 16 of them in detail. While all of these sants are lauded for their realization of the ultimate truth through Dādū, they are extolled for self-realization and perfection by the means of bhakti and yoga. A few of them are singled out for their translations and poetry, as well as their expertise on Sanskrit texts popular among the Advaitins like Yogavāśiṣta, Prabodha Candrodya, Bhagvatgītā, and the Upaniṣads. Then the Bhaktamāl goes on to give accounts of a few of Dādū's third-generation disciples. In this context of describing those Dādū Panthīs, who were also contemporaries of the author Rāghavdās, the Bhaktamāl mentions a connection between the Marwar royal polity and the Dādū Panthī community. The Marwar kingdom may have been patronizing the Dādū Panthīs from an earlier period than that of Rāghavdās. However, it is during King Jaswant Singh's time that the Bhaktamāl descriptions are corroborated by land-grant records. The Banaras-educated Dādū Panthīs emerge as the prime beneficiaries in such land deeds. Jaswant Singh's land grants to the Dādū Panthīs set a model for the later kings of Marwar, because almost all kings of Jodhpur until Man Singh (d. 1843) refer to the earlier example set by Jaswant Singh when they gave or reinstated grants and concessions to their contemporary Dādū Panthīs. Therefore, Jaswant Singh's land grants will be the subject of close study in this section. Through this exposition, we will see that the community's presence in Marwar was strong and enduring.

Themes in the works of Jaswant Singh on Vedānta and Brajbhāṣā aesthetics overlap with the works of Dādū's foremost scholarly disciple Sundardās, a contemporary of the Marwar king. Besides Jaswant Singh, the Maratha king Shivaji's court poet Bhūṣaṇ Tripāṭhī adopted, or rather politicized, Vedānta ideals for ideal kingship. A prominent Mughal example of the Vedānta paradigm's usage for the purposes of kingship is that of Prince Dara Shukoh. Therefore, we see that the Dādū Panthī case in Marwar of the 1660–70s is part of a wider phenomenon wherein the Mughal and Rajput kings were drawn towards the Vedānta paradigm for kingly self-fashioning.

The renewed prominence of Vedānta, especially Advaita Vedānta, in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is associated with the growing participation of Banaras-based Sanskrit Pandits (Brahman scholars) in major theological discussions.Footnote 70 Describing a process that helped Banaras re-emerge as a major city in Mughal India, Rosalind O'Hanlon writes that Banaras was an unrivalled centre of education where the learned could benefit from the well-connected networks of sponsors and the pious could find wealthy patrons.Footnote 71 The Pandit communities of Banaras supplied the moral and judicial authority over matters pertaining to ‘Hindus’ that Muslim state officials did not have. Due to these opportunities in the Mughal setting, the Brahman Pandits in Banaras could invest authority in themselves in matters of religious law. Similarly, in mapping the social history of Advaita Vedānta in early modern India, Christopher Minkowski remarks on the importance of Banaras from a theological point of view. Banaras became a major centre of the production of Sanskrit works on Advaita Vedānta, and the city became connected to South India through the networks of Pandits. Eminent Vedāntins of the period lived in the city, and Advaita Vedānta became the most common intellectual idiom for theological debates happening in Banaras.Footnote 72 These Pandits represented Advaita philosophy as a broad concept within Hinduism, under which the different and contesting belief systems of the time could function.Footnote 73 The Sanskrit Vedāntic texts that were vernacularized in this period include the eleventh/twelfth-century Sanskrit allegorical drama Prabodha Candrodaya (The Moonrise of Realization), which extolled Banaras as a place for not only seeking liberation (moksha)—as the Hindu traditions believe—but also as a place for gaining discrimination (vivek). It is in the city of Banaras that the Upaniṣads are studied. By contemplating the knowledge of these texts, the attachment (moha) is destroyed. Take, for example, how Jaswant Singh, the king of Marwar, praises Banaras in his Prabodh Nāṭak (drama of enlightenment), a Brajbhāṣā prose and poetic adaptation of the Prabodha Candrodaya:

Seeing it, sorrow is erased, and joy arises constantly,

The one that undoubtedly attracts the heart that is the city of Shiva.

Jaswant Singh's use of Vedāntic themes shows that, in addition to being widespread among the Sanskrit Pandits of Banaras, Vedānta philosophy was gaining prominence in the discourse of Mughal kingship—as shown by Munis Faruqi and Supriya Gandhi in the case of Dara Shikoh.Footnote 75 Additionally, it was finding relevance in the models of Rajput kingship in North India. With the rising status of Vedānta, the Brajbhāṣā courtly kāvya (poetics) tradition presented their patron kings with the title of an enlightened individual. With such epithets, the kings were now presented as those who bring together various religious traditions or transcend them. Take, for example, how the Maratha king Shivaji's court poet, Bhūṣaṇ Tripāṭhī, presents the king with the epithet of jñānī in his śivrāj bhūṣaṇ (Ornaments for King śivājī, 1673):

Loving both the nirguṇa and saguṇa [forms of the godhead] is the nature of an enlightened one,

Revealing who is virtuous and who is not, Shivaji then bestows charity.

Using the art of the pun, the text ‘adorns’ Shivaji with several epithets/ornaments, ‘bhūṣaṇ’, as its title suggests. The particular bhakti modes described in the first line of the verse above (nirguṇ and saguṇ) are taken literally in the second line by saying: after seeing who is good and who is bad, then Shivaji bestows charity (on the good people). The verse suggests that the true virtue of being a jñānī is actually exhibited by kings like Shivaji.

There is evidence that some bhakti communities, by the seventeenth century, show a trend of both participating in the Vedānta-related discourses and going to Banaras for training. The Marathi poet-saint Eknāth (d. 1599), who was well-positioned in the Brahman migration pattern from northern Deccan to Banaras, set an example of going to Banaras.Footnote 77 The nirguṇ bhakti sects like the Dādū Panth and Niranjanī Sampradāya became increasingly involved with Vedānta learning both by translating Vedānta works and by giving the philosophy a place in their poetic anthologies.Footnote 78 The Dādū Panthīs started participating in Vedānta-related intellectual discourses in order to bestow high philosophical ideals on their community and devotional practices. It is no coincidence that one of the three major Brajbhāṣā adaptations of the Sanskrit drama Prabodha Candrodaya was authored by Jangopāl, the author of Dādū's hagiography discussed in the first section of the article. The other two major adaptations were from the Brajbhāṣā court poet Keśavdās (fl. sixteenth century) and the Marwar king Jaswant Singh.

In his Brajbhāṣā rendering, known as the moha vivek granth or moha vivek yuddh, Jangopāl first claims Dādū's philosophy to be representative of nirguṇ bhakti and then goes on to tell the allegorical story of the war between the armies of discrimination/discretion (viveka) and attachment/delusion (moha), as depicted in the Sanskrit drama.Footnote 79 The success of Jangopāl's text, in comparison to the courtly adaptations, lies in its fame among the Jain intellectuals circles of Agra, who not only named Jangopāl's poem as their source of inspiration but reshaped the text according to Jain beliefs.Footnote 80 There is a debate about the possibility of attributing the Jain version of moha viveka yoddh to the merchant Banārasīdās—author of the famous autobiography Ardhakathānaka (A Half Story, 1641 ce). Jangopāl's Brajbhāṣā rendering of the Prabodha Candrodaya, however, was not exceptional in terms of the Dādū Panthīs’ engagement with Vedānta. From the first decade of the seventeenth century, a few Dādū Panthīs went to Banaras to study and compose scholarly Brajbhāṣā works on Vedānta. The tradition of Dādū Panthīs going to Banaras would only flourish in the coming centuries. Before we proceed to discuss the content of the works of Banaras-trained Dādū Panthīs, we should first situate them within the archive of land deeds and hagiographies.

The Bhaktamāl of Rāghavdās narrates the life events of two disciples of Dādū, Sundardās and Nārāyaṇdās (seventeenth century). The Bhaktamāl precisely notes that Sundardās's knowledge of Vedānta was learned while in Banaras.Footnote 81 Sundardās spent almost two decades in Banaras and returned to Rajasthan in 1625. A satirical couplet attributed to Sundardās mentions Nārāyaṇdās accompanying him during their study in Banaras:

[You] studied in Banaras, [now] residing at the [village] Virāvā,

Remained engrossed in the desert region, well done, Nārāyaṇdās!

Sundardās mentions Marwar's desert geography in his other verses on the region. He mostly lived in Fatehpur-Shekhawati, which is linguistically a Marwari-speaking area but politically a semi-autonomous region of its own. Sundardās's companion Nārāyaṇdās, on the other hand, was based in the Marwar kingdom. The abovementioned couplet and other examples suggest that both Sundardās and Nārāyaṇdās kept visiting each other. Evidence of possible interactions between the two is also found in a record of donations at Sundardās's monastery in Fatehpur-Shekhawati.Footnote 83 It is this Nārāyaṇdās, a Dādū Panthī of landholding pastoral community origin, who was honoured by King Jaswant Singh, as Rāghavdās's Bhaktamāl mentions:

Narayaṇ, subsisting on milk, had Ghaṛsīdās as a mighty guru,

King Jaswant invited [him], sending conveyance.

The above hagiographic description of Nārāyaṇdās is corroborated by the courtly records of Jodhpur. A special edict mentions that Jaswant Singh gave a land grant to Nārāyaṇdās to build a monastery, together with five tax-free farms, a public watering place, and a well for public use in the village of Cāmpāsar, north of Jodhpur. These deeds were issued while the king was in Aurangabad and Ahmedabad in 1667 and 1671 respectively. Relevant portions from the courtly register are given here with translations:

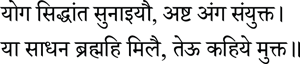

Figures 1 and 2. Khās rukkā –1 (Special edict–1), pp. 208–209. Source: Courtesy of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur (hereafter MMT).

On Monday, the fourteenth of the light-half of the lunar month Vaiśākh, at the fort location of Jodhpur. From the order of himself Shri Jalam Singhji, the son of the lord of the kings the great monarch Shri Vijay Singhji. And in the village Cāmpāsar where lies Dādū Panthī Haridās and Nevalrām's abode, five tax-free farms of irrigated land with one public watering place including a well for public use. An edict regarding these places was issued by King Ajit Singhji in 1708 (vs 1765) on the fourteenth of the dark-half of the month of Aṣāṛh. Based on that donation an order is given even now that these places will be held by the posterity of the Dādū Panthī's disciples Manīrām and Cetandās.

A copy of the edict of his highness. From the order of Shri Abhay Singhji

And in the village Cāmpāsar where there is the abode of Swami Nārāyaṇdās with five farms

For those [farms] there are two earlier deeds which were issued under the protection of King Jaswant Singhji.

Based on that donation an order is issued even now that these places will be given to Swami Haridās and Nevalrām.

A description of two deeds:

Deed 1, 1667 (vs 1724) on the fourth of dark-half of the month Kārtik from Aurangabad.

Deed 1, 1671 (vs 1728) on the third of light-half of the month Bhādrapad from Ahmedabad's two deeds.

Record of five tax-free farms of irrigated land with one public watering place and a well for public use.

The edict notes that the land grant that Jaswant Singh gave to Nārāyaṇdās was first recorded in 1708 in a notification during the time of King Ajit Singh. While issuing the notification about the Dādū Panthīs’ rights on the same land, Ajit Singh relied on the written deeds from the time of his father Jaswant Singh.Footnote 85 When we read the Bhaktamāl description, which was written in 1660, alongside the courtly edicts issued to Nārāyaṇdās by Jaswant Singh a few years later in 1667 and 1671, we see that the interactions between the sant and the king went on for a longer period. Notably, the support that was initially established by Jaswant Singh forms a long history of patronage of Dādū Panthī individuals by this Rajput state. As the edict shows, later kings of Jodhpur, namely Ajit Singh, Abhay Singh, and Vijay Singh, all accepted Jaswant Singh's earlier deed and recognized the rights of the contemporaneous Dādū Panthīs to the monastery.Footnote 86 This is, of course, just one early example of several land grants, concessions, and donations that the Dādū Panthīs received from Marwar kings, particularly in the eighteenth century. This courtly patronage played a big role in establishing the Dādū Panth in Marwar, thereby forming the influential presence that the sect enjoyed until the late nineteenth century.Footnote 87

The patronage networks of the Dādū Panth in Marwar show that, in addition to the warrior ascetics among the Dādū Panthīs, several individuals and their respective institutions received handsome financial support in Marwar throughout the eighteenth century. As evidenced by the land grants of Jaswant Singh to Nārāyaṇdās, future kings followed that example. Abhay Singh (r. 1724–1749) not only renewed contemporaneous Dādū Panthīs’ rights over Nārāyaṇdās's monastery but also gave protection to mahant Kṛṣṇadev who fled from the Dādū Panthī centre in Naraina to avoid pressures from the Jaipur king Sawai Jai Singh's statecraft policies.Footnote 88 Kṛṣṇadev lived in Merta (a major town of the Marwar kingdom) for many years. Court chronicles note that the Dādū Panthīs’ place in Merta was one of the prominent religious locations in the town, and King Abhay Singh awarded land grants to it:

Half of the property of the Dādū Panthī saint was given during the reign of King Abhai Singh.

Several court edicts of Marwar show an increase in patronage of the Dādū Panthīs in the region during the mid-eighteenth century. It was in Vijay Singh's reign (1752–93) that the Dādū Panthīs built their first monastery in the city of Jodhpur.Footnote 90 The kings Vijay Singh and Bhim Singh (r. 1793–1803) are noteworthy for having given immense support and recognition to the Dādū Panthīs in the sub-districts of Nagaur and Merta.Footnote 91 Dādū Panthī individuals were given one rupee from each village in Merta.Footnote 92 Because of this royal patronage, the centre in Merta rose in importance to become second only to the Dādū Panthīs’ main shrine in Naraina.Footnote 93 Man Singh helped the Dādū Panthīs with their temple-building project in 1827–8 in Naraina.Footnote 94 The Dādū Panthīs enjoyed high power in Marwar at least until the late nineteenth century, as noted in the Hindi Census Report of Marwar in 1891:

There is such a high level of honor (kurab) of the [Dādū Panthī] mahants of Naraina in Jaipur and Jodhpur. They only come with an invitation sending special notifications (khās rukkā). Chieftains (sardār) and ministers (dīwān) go all the way to the entrance of the capital-city (rājdhānī) to greet them. Even the kings (Maharaja Sahib) go to meet them in their camps.Footnote 95

The Vedānta of Sundardās and King Jaswant Singh

Sundardās's and Jaswant Singh's texts share themes in that they both describe the omnipresent supreme in purely nirguṇ devotional terms.Footnote 96 Jaswant Singh goes a step further, however, in not giving Vaiṣṇava devotion any significant place in his works on Vedānta. Therefore this section demonstrates that there is evidence for intellectual exchanges that happened between the Dādū Panthīs and the Marwar king. The works of Nārāyaṇdās, the sant who received land grants from Jaswant Singh, are unfortunately not well preserved, but one of his scholarly texts, the brahmaguṇa (Virtues of the Brahman), shows that he composed poetry on philosophical topics such as Sāṁkhya.Footnote 97 The works of Sundardās, however, were circulated widely, and surprisingly were commissioned by the poet himself to be compiled into a single manuscript, completed in 1685 ce. This kind of care for writing and compiling one's own work is rarely observed among sants.Footnote 98 I have explored elsewhere Sundardās's engagements with the aesthetic tradition of Brajbhāṣā courtly poetry, of which Jaswant Singh is known to be a master.Footnote 99 A brief overview of Sundardās's corpus, however, is warranted to give an idea of how aesthetically skilful his poetry is. Sundardās is very critical of poetry that doesn't follow the rules of poetics, namely prosody and rhetorical theory, because he wants sant poetry to be pleasurable for both the ‘assembly of poets’ and for the connoisseurs (as well as for devotees). His 13 octaves—verse sets of eight or more lines—show not only his philosophical expositions on Vedānta, Sufism, and bhakti but also his multilingual talents. These octaves are written in a Brajbhāṣā template with registers of Purabi (eastern Hindi), Punjabi, Rekhta, Persian, and Sanskrit.Footnote 100 His shorter works include philosophical poetry on the 52 letters of the Nāgarī alphabet and riddles on literary conventions, and some allude to the practice of writing dictionaries. It would not be an exaggeration to call Sundardās one of the first and foremost poets of early modern Hindi who used many proverbs of various North Indian dialects and philosophical maxims of Sanskrit for didactic purposes. He not only presented himself as learned in the classical tradition of Sanskrit but also as conversant with the newly emerging Brajbhāṣā courtly poetry by composing in the style of extemporaneous compositions as well as complex pictorial poetry on theological topics.

A comparison of Sundardas's major scholarly works, the Jñāna-Samudra (The Ocean of Knowledge, 1653) and a collection of quatrains (savaiyās), with Jaswant Singh's key Advaita Vedānta work Siddhānta-Sāra (Essence of Philosophies) reveals their distinct positions on bhakti and Advaita Vedānta. Both Jaswant Singh and Sundardās predominantly used quatrain meters, which was a prominent style of courtly Brajbhāṣā poetry.Footnote 101 Additionally, the fact that manuscripts of Jaswant Singh's texts on Vedānta are found in Dādū Panthī collections and that Sundardās's texts are preserved in the Jodhpur palace's manuscript collection—started by none other than Jaswant Singh himself—also confirms exchanges between these traditions and institutions that kept their works and memories alive.Footnote 102 The Advaita theme is widely present in Jaswant Singh's less-studied and shorter texts. This is evident in his Prabodh Nāṭak, which is an adaptation of the eleventh/twelfth-century Sanskrit drama discussed earlier, the Prabodha Candrodaya. In this adapted Brajbhāṣā prose drama, all characters are translated according to the Sanskrit original, except for one major character: viṣṇūbhakti (‘devotion to Vishnu’). Jaswant Singh translates viṣṇūbhakti simply as āstikatā, which is comparatively a more open-ended term meaning belief or piety. Jaswant Singh disregarded Vaiṣṇava bhakti and took a purely Advaita stand in his Siddhānta-Sāra as well. In this text, he presents each of the philosophies in a gradual progression, with Sāmkhya and yoga as subsidiary to Advaita Vedānta. Jaswant Singh describes a practitioner's gradual progression in Vedānta thoughts while integrating them with the four life stages (aśrama) of Hindus. Being less interested in presenting the intricacies of bhakti and yoga, Jaswant Singh rejects all of these philosophies, calling them ‘mistaken’ (bhram), and attempts to assert his uncompromising Advaita position:

By miscognition different types of Ishwara are created from the Brahman .

Then considering them to be nirguṇ and saguṇ, worldly practices went on in illusion.

There is a pun in the three underlined words above, which aver that the supreme brahmn is true and other ‘manifestations’ are false or mere ignorance, that is, bhram. By negating Vaiṣṇava devotion and only validating Advaita thought, Jaswant Singh was also making a ‘doctrinal’ position. This agrees with the abstraction of the supreme truth rather than the absorption of all religious forms into a cosmic whole via embodied and ritual means which is the realm of Vaiṣṇava devotion. The above description is very much in harmony with the new culture of debate introduced at the Mughal court, as discussed in previous sections. Jaswant Singh's interests in Vedānta are concurrent with Dara Shukoh's positions on Vedānta whose claim for imperial succession Jaswant Singh supported. In the Jñāna-Samudra, on the other hand, Sundardās takes a great interest in describing bhakti, yoga, and Advaita Vedānta equally in order to abstract each of the knowledge systems. Sundardās uses Advaita Vedānta philosophy to reformulate earlier debates on nirguṇ versus saguṇ modes of devotion, where he stratifies various bhakti(s) such as the nine-fold (navadhā), and supreme love (prema) by placing the qualified non-dualist devotion (parā-bhakti) at the top. Under the wide umbrella of jñāna (gnosis) and overarching Advaita Vedānta, he asserts that bhakti and yoga (of contemplation) are also liberating theologies in their own right:

[I have] narrated the theory of Yoga, integrated with its eight parts (aṣṭa anga),

Through this practice those who unite with the Brahman, are called liberated (mukta).Footnote 104

Non-dualist thought forms the central theme in Sundardās's corpus, and he self-identifies with the jñānīs of the non-dualist sort. In his ‘collection of quatrains’, Sundardās integrates ‘knowing with experience’ (ātmānubhava) into his main philosophical position. By doing so, Sundardās not only juxtaposes his nirguṇ devotion to the Vedāntic idea of gnosis but also downplays the importance of the six philosophies.Footnote 105

Dādū Panthī networks expand among the bardic poets

The Dādū Panthīs successfully spread to Marwar the seventeenth-century literary culture which formed in Banaras, Fatehpur Sikri, and Amber, and which resonated with the new Mughal imperial paradigm. The ever-growing prominence of Vedānta reveals that this expansion was related to the spread of a new imperial culture as well as the predominance of abstract and intellectualized manifestations of religion over the felt and embodied forms of temple Hinduism. This state patronage intensified interactions among the Dādū Panthīs and members of the Cāraṇ community, literary composers, and performers who are now referred to as ‘bards’ but were actually much more, being expert poets. By tracing Dādū Panthī networks in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh through the literary community of the Cāraṇs, we can see that ornate courtly literature and Vedānta had sustained purchase in such exchanges. Examples of this change include the presence of Sundardās's scholarly texts in the syllabus of the court poetry school of Bhuj, Gujarat, in the mid-eighteenth century and the Dādū Panthīs’ composition of hagiography in Marwari and their influential presence in the court of Bundi.

Michael Allen has studied a great example wherein the Bundi king invited the Dādū Panthī, Banaras-trained Advaitin Niścaldās (d. 1863) to his court.Footnote 106 Niścaldās's Vedānta text Vicār Sāgar (The Ocean of Inquiry) was highly praised, including by the later monk Svami Vivekananda. What is of concern here, however, is the growing tradition and culture of exchange between Dādū Panthīs and courtly Cāraṇ poets, the well-honoured guides of Rajput kings. An example of this exchange is the multilingual poet and last great master of Marwari at the Bundi court, Suryamall Misan (1815–68), who precisely notes that he learned Advait Vedānta from a fellow Cāraṇ, Svarūpdās Dethā (d. 1863).Footnote 107 The latter was a Dādū Panthī sant in the disciple tradition of Rajab. At the beginning of his magnum opus, the Vamsh Bhaskar (The Sun Clan, circa 1841–57), Suryamall pays tribute to his mentor Svarūpdās in Sanskrit:

In brief, I was taught the treatise of Pantañjali together with the commentary of King Bhoja, the unassailable (dustarkyā) manual for poets by Mammaṭa, the shorter works of Advaita, and the science of categories (tattva) in Nyāya and Kaṇāda (Vaiśeṣika). I bow deeply (bāḍham) to that teacher of generous mind (udāracetana) who taught these to me—the Abode of Pure Form, Svarūpa.Footnote 108

This verse exemplifies the knowledge systems that were important for the training of a Dādū Panthī sant like Svarūpdās Dethā at this time. It is arguably the culmination of the process we see, beginning with the training of Sundardās mentioned in the previous sections of this article. This exchange between two intellectuals of the same caste background tells us the importance of the Cāraṇ community networks across regional courts.

The growing contact between the Cāraṇ community and the Dādū Panth goes back to Dādū himself. During his visit to the Marwar region, Dursā Āṛhā—who is revered as one of the finest poets of Marwari and was greatly honoured by the kings of the Marwar, Mewar, and Sirohi states—is said to have met with Dādū.Footnote 109 In this interaction, Dādū confirms the Cāraṇ Dursā Āṛhā's firm devotion to the formless godhead (who resides within) rather than to incarnations of Vishnu which were becoming popular among bards at this time. Another interaction with Dursā Āṛhā that is famous in Dādū Panthī hagiography was that of Rajab, an expert poet and the foremost disciple of Dādū. In the Bhaktamāl of Rāghavdās, Rajab is said to have defeated Dursā Āṛhā in a literary feat, thus making Rajab a better poet than the accomplished local bard.Footnote 110 Beyond hagiography, the Dādū Panthīs took an interest in the poetry of the Cāraṇs, including Dursā Āṛhā, as their poetry is evidently preserved in the Dādū Panthī manuscripts.Footnote 111 An interesting case of how the bardic community turned towards composing devotional poetry, in which the Dādū Panthīs were already outshining locals, is the poet-saint Brahmadās. Brahmadās was a Dādū Panthī who composed a Bhagatmāl (or rather six shorter ones) in Marwari during King Vijay Singh's reign in the eighteenth century.Footnote 112 With this Bhagatmāl(s), Brahmadās recontextualized the widely circulating Brajbhāṣā Bhaktamāl tradition, started by Rāmānandī Nābhādās (fl. 1600), for a Marwari literary milieu. Composed in one of the most difficult literary styles of bards (in vayaṇ sagāī alliteration), which was highly regarded among the bardic poets of Marwar, this Bhagatmāl gives considerable space to regional holy men and devotional communities. It also blends Vaiṣṇava traditions with sant bhakti.

The Cāraṇ caste was widespread in northwestern India. Two larger sub-groups of Cāraṇs—those who had origins in Marwar and those who hailed from Kutch in Gujarat—were spread out in the states known today as Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan.Footnote 113 Through the use of the shared literary idiom of Marwari, the Cāraṇ poets brought these regions together. A prominent example of this process was the Cāraṇ poet Hammīrdān Ratnu of Marwar, who became the mentor to Kutch's King Rao Desal (r. 1718–41). Networks of Cāraṇ poets like Hammīrdān Ratnu were arguably the reason why the Dādū Panthī Sundardās's poetry reached from Marwar to Kutch, Gujarat. The Kutch state's manuscript collection in Bhuj shows that Sundardās's Jñāna-Samudra was prepared for Rao Desal's own study, and his texts were included on the syllabus of the unique Brajbhāṣā poetry school run by the state.Footnote 114 It is in the same bardic tradition in which Mangaldās (late nineteenth century), with his expertise in composing genealogies, presents the history of the warrior-ascetic branch of Dādū Panth.Footnote 115 Foremost among those members of the Cāraṇ community trained by Dādū Panthī monks is actually Swarūpdās Dethā, mentioned above, who later became the guru of kings in Sitamau and Ratlam in Madhya Pradesh. In addition to short texts on Vedānta themes, Swarūpdās Dethā composed the Rajasthani version of the epic Mahabharata—the Pāṇḍav Yaśendu Candrikā (The Moonrise of Fame of the Pāṇḍavas, 1839) which gained popularity in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh.

This is not an exhaustive account, but the examples above do show that the Dādū Panth had a defining impact on the literary and religious culture of the Marwar region and beyond. Through this influence not only did major genres like Bhaktamāl take new shape in Marwari but the history of the sect's warrior branch itself was narrated in the regional tradition of martial narrative composition. The tradition of learning, as well as the engagements with elite cultural discussions started by Dādū Panthīs like Jangopāl and Sundardās, came full circle in the nineteenth century when the community built networks with the foremost court poets and intellectuals in Marwar.

Conclusion

Jack Hawley has convincingly argued that bhakti, of which the Dādū Panthīs were a part, should be understood in its plural manifestations instead of a singular unified ‘movement’ or āndolan as it is called in Indian languages. Bhakti traditions were individually constituted yet formed networks with each other by participating in a shared religiosity through music, hagiographic narratives, literary genres, and tropes in several languages over centuries.Footnote 116 The long-held view that the sants worked in the realm of the public and were unconcerned with or mostly against political authority appear to be only fragmented understandings of bhakti.Footnote 117 We now know that agents like Brahmans, courtly elites, pastoral communities, artisans, and merchant communities, among many others, developed the bhakti networks connecting religious locations and trade centres in the early modern era.Footnote 118 The growth of the Dādū Panthī community over the course of three centuries fits this interpretation in terms of its spatial, caste, literary, and courtly networks. The example of the Dādū Panth outright contradicts the notion of those historians who presented the idea of the North Indian ‘Nirgun School’ that sants like Kabīr were ‘as a rule illiterate or very superficially read’.Footnote 119

In the article we have discussed that the Dādū Panth was part of a major shift in the history of the sant-bhakti tradition as its identity was formed in engagement with the new Mughal-Rajput imperial model. The community also participated in the discourses of this new model that was marked by the concept of sulh-i kull. What is important in this imperial model is that all religious communities, large and small, old and new, engaged with the Mughal court in order to justify their existence and establish their legitimacy. This shows the new imperial rationality at work that encouraged all communities to rethink and articulate anew their religious identity with reference to one another and to the empire. This kind of ‘registering’ is manifested not only in hagiographical and other literary forms discussed in the article but also in the memories and rhetoric that the inscriptions of Dādū Panthī monastic centres present. Such discourse depicts Dādū's disciples as existing side-by side with the Mughals and their noblemen or alongside Rajput Mansabdārs in their monastic centres of Rajasthan. The way in which the disciples are related to Dādū in such inscriptions displays a genealogical stability and empire-building order. Take, for example, this pillar inscription of Sundardās's monastery in Fatehpur of Shekhawati:

The inscription takes us back to the verse we read at the beginning of the article which showed a kind of ‘registering’ strategy on the part of Dādū and his disciple Rajab towards models of Mughal-Rajput ruling. The way in which the Dādū Panthīs relate to their guru equates with how noblemen relate to their emperor—that is, Dādū gives authority to his disciples, who take his message further, by creating a realm of spiritual rule. This was precisely the spirit in which Abu'l Fazl called the new era under Akbar the ‘caliphate of tahqiq’, that is, the empire of ‘verification’ and ‘realization’ of divine truth.Footnote 121

First growing out from the Amber region and then developing their main centre in Naraina during the later years of Dādū's lifetime, the seventeenth century saw Dādū's disciples expand their networks in Banaras, Fatehpur Sikari, Amber, and Marwar. In later centuries, this expansion of networks also included the bardic court poets. This process demonstrates that the Dādū Panthīs’ expertise, which included everything from skill in major intellectual discourses and knowledge system like Vedānta to command over ornate literary tradition and high skills in bhakti homiletics, was a major factor in their ascendancy.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the two anonymous readers, to the editor of Modern Asian Studies Norbert Peabody, to Azfar Moin who is the editor of this special issue, as well as to John (Jack) Hawley, David Lorenzen, Monika Horstmann, Cynthia Talbot, Andrew Ollett, Tyler Williams, and Sohini Pillai for their excellent feedback on an earlier draft of this article. I am thankful to Donald Davis for helping me understand a Sanskrit verse, and to Mahendra Singh Tanwar, Vikram Singh Bhati, and Prem Singh for their assistance with the archival records at the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur.

Competing interests

None.