Introduction

Between 1899 and 1943, British consuls were stationed in the seemingly remote Burma-China frontier region. From the perspective of British officials, the region was far removed from the bustling ports on the east coast of China and the towns and cities in lowland Burma. Between the winding hills and the valleys of the frontier, consuls represented British interests. But whose interests were they protecting, and how? Why did this matter, and to whom? This article examines the legal role of consuls stationed at Tengyue close to the Burma-China border. It argues that consular legal mediation on behalf of British subjects—including local ethnic populations claimed by British Burmese authorities as British subjects—became a central reason for the continued stationing of these frontier consuls. Consuls therefore not only promoted British consular interests in China, they also supported colonial Burmese authority and its claims to people, land, and resources across the Burma-China frontier, which were often politically contested by China.

The establishment of British consular authority in China—as has been extensively documented in the historiography of modern Chinese history—stemmed from the Sino-British and Sino-Foreign treaties. From 1842 onwards, the Qing empire conceded legal, commercial, and residence privileges to Britain and thereafter various other foreign nations. These rights formed a central part of British imperialism in China. Although all of these privileges were collectively referred to as ‘extraterritoriality’, its strict definition pertained to law: the right to exercise a nation's law in a foreign land. By and large, this right was entrusted to British consuls. They often lauded extraterritoriality as both a symbolic and real freedom from a supposedly corrupt, arbitrary, and very alien Chinese legal system, which allowed them to adjudicate when British subjects were defendants in any suit or case. Among other advantages, this enabled British consuls to help protect and support rights relating to British commerce and determine the fate of British subjects who were accused of criminal offences. This was of particular importance on the east coast where treaty ports were opened for a community of foreign sojourners, residents, and businesses with strong connections to maritime trade.

However, by the early twentieth century, the exercise of British extraterritoriality also spread inland and west, converging with British colonial expansion from British India. This meeting of different forms of British authority came together at the frontiers of Xinjian, Tibet and the Burma-Yunnan frontier.Footnote 1 In the latter case, as the Burmese monarchy paid tribute to China, Britain secured formal recognition from China over what Britain called ‘Upper Burma’ through the Sino-British treaty of 1886, followed by the Sino-British convention in 1894. This geographic area referred to the large central and northern parts of what is roughly understood as the contours of present-day Myanmar, including the northeastern mountainous regions incorporating the semi-autonomous Kachin hills and Shan States on the Burma-China frontier.Footnote 2 Following an amendment to the convention in 1897, consulates were established in the neighbouring Chinese province of Yunnan. One of these consulates near the frontier—Tengyue—remained open until 1942 despite its seemingly remote position. This article uncovers its importance for both consular and colonial interests across this frontier.

Examining the role of the Tengyue consuls sheds light on a largely neglected yet important part of British imperialism in Southeast Asia. Although histories of the frontier have received greater scholarly attention in recent years, the British presence in Yunnan and the Burma-China frontier in the colonial and imperial historiography of the British empire are still often forgotten or marginalized.Footnote 3 The most common references made to British activity in the region are to the murder of the British diplomat and explorer Augustus Margary in 1875, which led to the Sino-British Chefoo Convention (1876); the highly anticipated Mandalay-Yunnan railway, which was not constructed; the work of the small numbers of missionaries and travellers; and, more prominently, Sino-British border disputes.Footnote 4 This article therefore disrupts the popular narrative of extraterritoriality being exercised largely in relation to the east coast treaty ports with its larger foreign population and maritime trade.Footnote 5 It argues that the British imperial presence at the fringes of China were important for Burmese sovereign claims over people, resources, and lands in the frontier.

This article brings together renewed scholarly interest in the function of law in the British empire and the role of intermediaries in facilitating transnational connections more broadly. Outside of Shanghai, British consuls were the key agents administering law and negotiating legal issues with Chinese officials. However, little research has been done on their duties.Footnote 6 The legal functions of the consuls also add a different perspective on the already popular theme on ‘borderlands’ in historiography on China which has focused overwhelmingly on the social, cultural, political, and economic aspects of Chinese relations between state and society.Footnote 7 This article underlines how consuls were enactors and mediators of law at the frontier. It emphasizes the necessity of examining trans-regional and trans-imperial perspectives that reflect the realities of how everyday lifestyles that transcended political borders shaped the imperial jurisdiction and sovereignty claims in the frontier.

The article is split into two parts. The first shows how British economic and political aims faded after the establishment of the consulate. Consular case reports are used to demonstrate the nature and continued importance of the consul's representation of British and other foreign subjects. The second section demonstrates how the consuls were also mediators between Burmese and Chinese authorities in trans-frontier cases. The majority of the sources forming the archival basis for this article date from 1909–1931, when the British consuls and Burmese officers produced more regular and detailed reports. Though a consular presence remained between 1932 and 1943, consular activities were disrupted by war and political instability in west Yunnan until the abolition of consular jurisdiction in 1943. As well as using travelogues, customs returns, and administrative reports of both colonial British Burma and British consular records from China, this article also draws on the rich records of the Sino-British ‘frontier meetings’ on trans-frontier cases as well as local consular correspondence.Footnote 8 The focus is upon the British consuls’ aims and actions rather than on an attempt to illuminate the actions or perceptions of the local population or Chinese authorities. It has therefore relied upon British reports, adding Chinese perspectives as they appeared in the British reports and were connected to how the British consuls understood their roles. Using such colonial documents requires a cautious analysis. As Patterson Giersch has warned regarding those reading Chinese imperial sources on the southwestern frontier, colonial documents tend to overstate the reach of the state and its agents over local populations on the frontier.Footnote 9 The article is therefore careful to avoid claims about the extent or effectiveness of consular authority, but instead outlines how the British consuls and Burmese officers near the frontier understood their own roles and objectives.Footnote 10

Establishing consulates and the importance of law: mediating and representing British and European subjects

British extraterritoriality was reliant on consular officers as the key agents of administering its authority. In theory, extraterritoriality could be exercised anywhere within the territory of China from 1833, following metropolitan enactment of the China Order in Council of that year. However, Chinese sanction was necessary for the stationing of a consulate over which locality a consul could exercise his powers. Until the 1890s, these consulates were nearly all located on the east coast or inland where there were short waterway links to the coast, reflecting the importance of maritime trade. By the turn of the twentieth century, consulates were being opened further inland—the upper reaches of the Yangzi in central China, such as Hankou (Hankow), and further west in the Chinese province of Sichuan, such as Chongqing (Chungking).

In the case of Yunnan, British officials and merchants aimed to facilitate trade to and from both India and Burma to inland China, developing both terrestrial and inland riverine trade routes for the transit of commodities to the east coast. They also hoped that the market for local products such as regional teas could be developed and also transported eastwards. These economic aims were also tied up with concerns over European geopolitical competition. In Tibet and northwestern China, Anglo-Russian rivalry had resulted in the stationing of a British agent from the Indian civil service in Kashgar following the economic privileges granted to Russia in the region and the stationing of a Russian consul. Likewise in southwestern China, a French presence in Southeast Asia and the accompanying economic privileges impelled the British to contest control over river trade to the interior of China, the railways, and mining rights. For Britain, these concerns were exacerbated by French influence in the wider region to the south; by 1890, following the conclusion of the Sino-French war and Tianjin Accord (1884–1885), France's sphere of influence included Cochin China (present-day South Vietnam) as a French colony, and Annam, Laos, and Tonkin in the north (bordering Yunnan) as French protectorates. A French presence also extended into China, with a consulate in Longzhou (Lungchou) in 1889, in the southwest province of Guangxi (Kwanghsi), and the leased territory of Guangzhouwan (Kwangchowan) on the south coast of Guangdong following the Franco-Chinese agreement of 1892 (enforced from 1898). France had also obtained rights to build a railroad from Tonkin to Kunming as well as mining rights. The British presence in Hong Kong and Burma, and the French presence in Guangxi and Indochina, therefore left the province of Yunnan as a contested zone for Anglo-French interests. Britain not only wanted to check French influence, but also keep its policymakers informed about French designs in the area. For this reason, the stationing of British consulates was seen as a marker of imperial presence against increasing French influence and an important listening post for intelligence on French activities—from political designs to scientific and religious missions—which formed a central impetus for the opening the consulates.Footnote 11

From the turn of the century, two consulates and a consulate-general were subsequently opened. They were located in Simao (Ssumao/Szemao),Footnote 12 Kunming (Yunnanfu), and Tengyue (Tengyueh) (see Figure 1, below). The consulate-general in Kunming, established in 1902, oversaw British interests in the more prosperous central and eastern parts of the province. The consul-general also represented British interests in the neighbouring province of Guizhou and resolved issues arising on the provincial borders between Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guangxi to the north and west. The consul-general supported the Tengyue consuls, using his elevated status to relay information and negotiate on behalf of the consuls on questions that required the consent or acknowledgement of the provincial Yunnan authorities in Kunming. The consulate in Simao, south Yunnan, was intended primarily as a lookout post near the Sino-Indochina border, but its location was deemed unsuitable for information-gathering about French activities and it quickly closed, maintaining only a customs officer. However, even British economic prospects in Simao remained limited. Although located on the long, main caravan route between Yunnan and Burma, it remained largely inaccessible for interlinking with the east coast trade routes, functioning instead as a local and regional distribution centre for frontier transit goods.Footnote 13 Hopes for Simao being a part of a transit route for goods to and from Indochina and Yunnan were also dashed from 1910, when the French Hanoi-Kunming railway became the main transit route for trans-frontier goods to and from this region.Footnote 14 In the end, despite some increases in trans-frontier trade in the first two decades after its opening, Simao was regarded as a ‘failure’.Footnote 15

Figure 1. Location in the early twentieth century of and the consulates of Tengyue and Simao, and the consulate-general of Kunming, with approximate Sino-Burmese borders. Source: Cartographic credit to Laura Vann.

The consulate at Tengyue in western Yunnan opened in 1899. Today the city is known as Tengchong, situated in Baoshan prefecture. It stands at an altitude of 5,400 feet (approximately 1,645 metres) at the edge of the Yunnan plateau; to the west and southwest, there are a series of valleys that constitute the Burma-China frontier.Footnote 16 At the turn of the twentieth century, the frontier incorporated areas ruled by local headmen, some of whom owed political alliance to Chinese authority. A large section of this was Shan territory, with Kachin groups inhabiting the encircling hills. Although the Sino-British convention (1894) and its amendment (1897) had attempted to draw a boundary between Burma and China, the Chinese authorities and local people often did not acknowledge such delimitations. Rigid political and jurisdictional demarcations did not sit well with frontier lifestyles and commerce; fields were located across desired markers, winding tracks ran through multiple hills and valleys, and merchants, migrants, farmers, families, and goods regularly moved from place to place. Despite this, one of the priorities of the British Burmese government, with the help of the Tengyue consuls, was to reinforce and draw boundaries to assert British sovereignty. This was an ongoing mission that had varied success. This assistance on frontier matters also included reporting on the local politics of the valley and hills populations. Economically speaking, Tengyue, like Simao, was a distribution centre rather than a production town, with imported goods (principally Burmese cotton from the Shan States) heading to the bigger regional town of Dali (Talifu) and tea and metals exported to Burma.Footnote 17 In turn, these items were distributed beyond Yunnan to other parts of inland China. As well as salt, this included the illegal production of trade in opium transported from fields in the Shan States.Footnote 18

This cross-border trade with Burma appealed to British officials who hoped to increase the flow of commerce and strengthen ties with the Burmese town of Bhamo and its resident deputy commissioner, stationed around seven days’ travel from Tengyue. However, Tengyue and its trade prospects immediately disappointed the consuls and foreign visitors. Shortly after its opening in 1902, the Australian traveller George Morrison scathingly described the town as ‘more a park than a town’, with the space within the city walls consisting largely of ‘waste land or gardens’.Footnote 19 Travelling to and from Tengyue was time consuming and sometimes hazardous. To the west, the Burma trade routes were mostly pony tracks in hilly terrain, and to the east, towards the Yunnan capital of Kunming, were a series of steep ascents reaching to 8,000 feet (approximately 2,438 metres). The British official and traveller Edward Colborne Baber summarized the difficulties of travel with reference to a traditional Chinese proverb: travelling across Yunnan was described as ‘chi Yunnan ku’ (‘eating the bitterness of Yunnan’).Footnote 20 British officials soon discovered that the prospects for trans-frontier trade were also too limited for British interests. Hill tracks were only serviceable for the smaller scale transit of goods via mules. The rainy season from June–September rendered some of these tracks unserviceable and the transit of goods on others slowed considerably during these months.Footnote 21 It was also difficult to monopolize trade given the reliance on local Chinese trading networks and their hostility to the presence of foreigners. This was similar to other inland cities in neighbouring Sichuan province opened to a consular presence. There, local anti-foreign sentiment had often turned violent, scaring away foreign merchants and allowing Chinese capital and businesses to strong-arm foreign interests out. A British consular presence therefore initially appeared to be of very limited use to British interests. The overall disappointment was best reflected by the proposed Mandalay to Yunnan railway. The highly anticipated railway, aiming to obviate all these difficulties for trade and to compete with France, greatly excited British merchants and officials, but it was eventually deemed unviable and the plans were dropped.Footnote 22

Despite the disappointment over economic and political prospects, not only did the consulate-general at Kunming remain open, but so did the consulate at Tengyue. For Kunming, there was an obvious explanation: the consulate-general could oversee and monitor foreign and Chinese trade in the more prosperous part of the province with stronger trade links to other cities. A consulate-general could also continue to report to the British consular authorities on the changes and developments of the Yunnan provincial government in Kunming, as well as keep an eye on the construction of the French Hanoi-Kunming railway and, later, its transported goods. However, for Tengyue, as a seemingly lonely outpost, it was the consul's frontier duties, specifically his legal role, that kept the consulate open. Unlike on the east coast, inland consuls had more responsibility for keeping the peace in places that were more hostile to the foreign presence than bustling ports. Although legal advice and oversight were provided by the chief judge of Her Majesty's Supreme Court for China (HMSC) who acted as a higher and appellate court judge in Shanghai, consuls were often left to their own devices. Untrained in law and with delayed communication to the east coast, they relied on their local knowledge—their understanding of the environment and local populations, and their relationship with Chinese officials—when they responded to legal issues.

For the consular district of Tengyue in western Yunnan, the distance from the east coast and the composition of the foreign community magnified the importance of this legal role and shaped the nature of its legal representation and mediation. Unlike many consular districts, the British and foreign population living in Tengyue and its close vicinity was particularly small. A decade after the opening of the consulate, there were just seven foreign subjects out of an estimated total population of 10,000 people in Tengyue.Footnote 23 Few British merchants ever made their way to the region. For example, at the end of 1917 in the western Yunnan district incorporating Tengyue, there was only one British merchant working as a sales agent for the British-American Tobacco Company at Dali (Talifu).Footnote 24 Without economic incentives, foreign subjects were usually drawn to western China to preach, venturing to the hills and valleys often untouched by European influence. By 1922, at least 75 foreign missionaries were resident in the whole province.Footnote 25 A number of these missionaries would have toured temporarily in the western region, although their exact numbers are hard to ascertain. They would have been joined by a number of expeditionary men and scientists who also made their way to the remote parts of Yunnan—such as the botanist George Forrest—intrigued by the flora and fauna of the region.

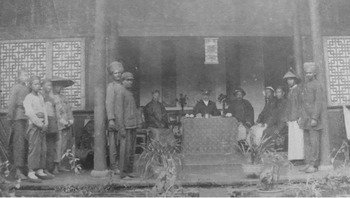

The composition of this foreign presence is reflected in the numbers and nature of consular legal issues in the returns of court statistics. The Tengyue consuls submitted only a handful of official reports of consular court hearings to Shanghai. Therefore although the first hearing was photographed and is memorialized in archive documents (see Figure 2), the image of holding court was more of a symbolic representation and display of power.

Figure 2. First consular court held at Tengyue, 1909. The British consul (centre) with local Chinese officials (immediate left and right) surrounded by British Sikh and Chinese court assistants (outer right and left). Source: TNA: FO 228/1733.

Of the cases that are listed in the consular court case returns and reports, most involved missionaries, travellers, and residents with names and affiliations that suggest a European racial heritage. Despite the small numbers, these cases often required a speedy resolution and could be sensitive when they arose. For both the Tengyue consul and Kunming consulate-general, these cases tended to involve two interrelated matters reflecting the perils of life in the southwestern province: inheritance and violent death. First, probate matters needed swift action. If the subject was male, often his wife, children, or other family members who depended on his income required speedy acquisition of the inheritance. This could allow them to move away from a place that afforded few opportunities for work or to a community of people to help them in their time of need. To dependent family members of the deceased in this region the consul's role was therefore of added importance. Second, although some of these deaths were attributed to disease or accident, there were several instances of murder. Such cases are not perhaps too surprising; the local population tended to be more suspicious of, and resistant to, foreigners than people on the east coast. Local grievances and anti-Qing protests could also turn into general anti-foreign action aimed at French and British subjects, and there were many anti-Christian and anti-missionary riots in parts of the Chinese interior.Footnote 26 The Tengyue consuls felt keenly the sentiments of local residents towards missionaries, who spent their time proselytizing not only to Han Chinese but also local ethnic groups who were usually even more wary of foreign people, customs, and beliefs. This meant there were plenty of opportunities for cultural and linguistic misunderstandings and offence to local customs. Foreigners could also be easy targets for robbers and kidnappers, who preyed on individuals who were less familiar with the area and were assumed to be wealthy. In these cases, the consul investigated or pressed the Chinese authorities to examine the case. As a result, in the early twentieth century the consuls negotiated with several tiers of Chinese administration regarding investigations into an attack or murder: frontier officials (mostly ‘administrative deputies’); district magistrates; district provincial officials sitting in Tengyue (until 1911, a daotai, and afterwards, usually a daoyin); provincial officials in Kunming; and, far less occasionally, the Chinese central government.

Three prominent cases in Yunnan that were recorded in detail reflect the consul's various roles. One was the suspected kidnapping and murder of D. F. Pike in 1929.Footnote 27 Pike was a missionary for the China Inland Mission and resident in southwest Guizhou province bordering Yunnan in 1929. He was presumed to have been kidnapped in the southwest of the province, but after no groups called for his ransom and no trace of him was found, Pike was believed to have been murdered. The Kunming consul-general followed up on the investigation, pressing both the local Yunnan and Guizhou officials for further enquiries, but ultimately, he felt that the Chinese authorities did not try hard enough to ascertain what had transpired and the case seems to have remained unresolved. In Simao, another case of murder was noteworthy as the victim was A. H. H. Abel, acting commissioner of the Simao customs.Footnote 28 It was believed that Abel had had a heated argument with his Chinese chef, who had subsequently stabbed the commissioner. Abel was found dead on the dining room floor of his home with the knife lodged in his left shoulder. Both cases suggest that although the population of British residents was small, criminal incidents involving British subjects were prominent because the consul needed to use his authority to help facilitate the resolution of Sino-British cases. The consul played a role in the initial investigation, the collection of evidence, and in pressing local Chinese authorities to pursue further enquiries. This latter role appears to have been a negotiating one as the consul often reported the need to pressurize the Chinese authorities into investigating criminal issues involving British subjects, reflecting the importance of the consul outside of the courtroom. Although there are just a few reported incidents in the records, it is likely that there were far more. In the Pike case, the incident only came to light because the consul required advice from HMSC on the issue of probate and special instructions: it was not possible to ascertain that Pike was indeed dead and Pike's widow had requested a settlement of his estate. Had the issue of his uncertain whereabouts and probate not occurred, the case may not have been recorded in the legal correspondence papers.

For the Tengyue station, one prominent murder case likewise stood out in the consular reports, and further demonstrates that British nationals were not the only subjects whom consuls represented. Owing to the remote location of the region, many foreign subjects had little or no locally stationed national representative to help them or represent them in legal matters. In 1909, reports came through to consul Archibald Rose of two murdered Germans in the Salween Valley frontier region. Local ‘Lutzu’ men were suspected of murdering Dr Brunhuber and Mr Schmitz who had made their way through their lands on an expedition and stopped at the village of ‘O-ma-ti’. The circumstances of their death were gathered from the Indian servant who was taken prisoner by the Lutzu.Footnote 29 The reason for the attack was not clear, but it was noted that the two Germans spoke neither Chinese nor the language of the attackers, and that a misunderstanding might have resulted which angered the local community.Footnote 30 The Tengyue consul was at hand to facilitate the arrest of the men by the local Chinese authorities, and a number of suspects were subsequently taken to Tengyue and imprisoned under Chinese guard (see Figure 3). The consul also relayed communication in Chinese of the Indian servant's eyewitness evidence, and other particulars of the case, to the daotai and prepared for the arrangement of the Germans’ estates.Footnote 31

Figure 3. Nine O-ma-ti villagers arrested and detained in Tengyue for the murder of two Germans in the frontier. Source: TNA: FO228/1733.

Although British consuls also helped European subjects without representation in the early period of the eastern treaty ports, providing assistance to other nationalities who had consular representatives elsewhere in China demonstrates the wider legal scope of the frontier consuls than those on the coast. The distance of the frontier from the bigger cities with stationed consuls from other nations made this a necessity. The Tengyue consul's pressure upon the Chinese authorities expedited the arrest and detention of suspects, and his linguistic and mediation skills helped to bring eyewitness testimony to the attention of the daotai (the local Chinese administrative superior official). Nor were the consuls only involved in cases concerning European subjects. At times they also became involved in matters relating to Japanese subjects in the frontier. Shortly before the German murder case, the Tengyue daotai communicated with consul Rose over the desired removal of Lieutenant-Colonel Hanasaka in the frontier, with Rose appearing to represent his interests and preparing a passage for him away from the frontier.Footnote 32 Although the British were suspicious towards Germans in the region during the Great War (and seemingly did not represent any during this period), consuls continued to record the movements of German and other foreign subjects in the region. This general representation and tracking of foreign subjects marked their frontier legal roles as more distinct from that of the consuls in the treaty ports of the east coast.

Mediation in Sino-British frontier meetings

Distinguishing the duties of frontier consulates even more sharply from other inland consuls was the role Tengyue consuls played in the mediation of Sino-British ‘trans-frontier’ cases. These were heard at so-called ‘frontier meetings’ or joint Sino-British courts. They involved an injured party who was a subject claimed by one side and a perpetrator claimed by the other. The people involved were local ethnic frontier groups, mainly Shans, Lisus, and Kachins, who populated each side of the frontier. Meetings heard criminal cases, involving anything from cattle thefts and petty assaults to raids and murders. The meetings were intended as a means to negotiate the payment of compensation according to a mutually agreed scale by the Chinese and Burmese frontier officers.Footnote 33 This method of resolving cases was based on local custom where, traditionally, wrongs were often righted by a form of payment in blood or kind. When compensation was agreed in the meetings, either the Chinese or Burmese government footed the bill for a monetary payment. Although some of the cases were seemingly of little importance, they had the potential to disturb the peace on the frontier. Feuds and riots could make the administration of both China and Burma more difficult, or spiral into general anti-Chinese or anti-British uprisings. In other cases, incidents could trigger sensitive territorial claims between Burma and China (as will be explored below).

Annual meetings were established after the Manai Agreement of 1902 in Nawngma (or Namhkam), with two courts of the first instance usually sitting simultaneously.Footnote 34 Another meeting was held at Sima from 1909, with a court of first instance. Unresolved cases could be sent to the appeal court, heard by the Chinese daotai or daoyin of Tengyue or a district magistrate, with a Burmese superintendent or deputy commissioner. The meetings continued to take place almost every year until 1925–1926, and then sporadically owing largely to political disturbances in Yunnan. A sawbwa or fuyi—a local headman with hereditary royal titles who ruled over his semi-autonomous region—gave advice to Burmese and Chinese officials on local customs and could also sit as an assessor.Footnote 35 In the courts of first instance, a Burmese assistant superintendent sat together with a Chinese district magistrate or an administrative deputy. The Tengyue consuls were involved in most of these meetings and played no small role in the duties performed by the consul. Indeed, as early as 1910, Archibald Rose remarked that ‘… the major portion of the work … [of the Tengyue consuls] … has been in connection with cases arising between the tribesmen subject to Great Britain and China’.Footnote 36

A consul's aim in these meetings was framed by British political policy pertaining to the frontier. As outlined by the ambassador at Beijing in 1909, British interests demanded the preservation of peace on the frontier. This was imperative for boundary marking, for administering frontier regions, and for preserving friendly Sino-British relations. As such, consuls could intervene or assert claims in cases where there was reason to believe that an unresolved case would lead to the security of the frontier being threatened.Footnote 37 This general principle shaped three main efforts and concerns of the consuls throughout successive meetings. First, they strove to resolve outstanding cases, even if this required them being heard again in the successive year's set of meetings, or rolled over again to the year after. Second, a ‘successful’ meeting was considered to be one that resolved as many cases as possible that were thought to be easily resolvable. Finally, when considering what claims to put forward, consuls tried to avoid exacerbating either local or broader Sino-British tensions. This meant that some cases were chosen carefully, unless it was considered that inaction or a failure to put it forward to a meeting would further disrupt frontier peace or undermine important British sovereignty claims. As such, firm assertions in these instances were deemed necessary.

With these aims, the consul played three roles in the meetings. First, with the status of an official to whom the British thought the Chinese authorities would give due respect, he acted as a linguistic translator and communicative intermediary. In this regard, the consuls were ably equipped. Consuls from the China Service were ‘China hands’ who understood Chinese language and culture, and therefore the customs and decorum necessary for successful engagement with the local Chinese authorities. They were also familiar with the formal and informal operation of the Chinese administrative system. The men chosen to staff the Tengyue consulate often had similar backgrounds that demonstrate these skills. One of the first permanent consuls was George John L'Establere Litton. Born in Ireland and educated at Eton school and the University of Oxford, he first became a cadet in the Straits Settlements in 1891. He entered the China Consular Service as a student interpreter in Beijing and then served as acting consul in Chongqing. Afterwards he was involved with the southwest frontier through his role in the Burma-China Frontier Delimitation Commission in 1899–1900, and became acting consul at Simao in 1900. He served as a consul for Tengyue in 1901–1902, at Kunming in 1902–1903, and again for Tengyue during 1904–1906. The next longer term consul serving Tengyue was Archibald Rose (1909–1911), who also started his career in China as a student interpreter at the British Legation in Beijing in 1897. Like Litton, he was appointed as a British consul at Chongqing in 1903, and subsequently served as a consul at Yantai (Chefoo), Ningbo (Ningpo), and Hangzhou (Hangchow), before arriving at Tengyue in 1908. He also travelled extensively around China, Mongolia, and Central Asia both before and after his Tengyue appointment. Later consuls, such as Arthur Ernest Eastes (1915–1917) and John Barr Affleck (1919–1921), also started as junior staff members in Beijing and found consular posts both before and after being stationed in Tengyue. Their shared background of Chinese language skills, understanding of Chinese culture, knowledge derived from travelling across China, and experience of representing British subjects made the Tengyue consuls suitable mediators between Burma and China in criminal cases. Although they were mediators, they were not impartial; their experience prepared them for understanding the Chinese standpoints, but with a view to how to use this knowledge to help them negotiate for British interests in Sino-British disputes.

The need for mediators was apparent from the opening of the consulate. Before 1899 the British Burmese authorities’ initial attempts to communicate with Chinese officials on trans-frontier issues were woefully inadequate. As the historian P. D. Coates has highlighted with regard to the establishment of the Yunnan consulates, letters sent in English from Burma lacked decorum and could be insulting to their intended Chinese recipients.Footnote 38 As a result, the first Tengyue consul, J. W. Jamieson, insisted that Tengyue consuls should become an intermediary for correspondence between Burmese and Chinese authorities. Although the Burmese authorities later used Chinese translators, the Tengyue consul and his Chinese staff helped to interpret the language and intentions of various Chinese officials in return letters addressed to the British Burmese officials. Consuls also forwarded petitions to the Chinese authorities from Burmese officials and helped argue the case for compensation deals made with Burma. For example, when a Chinese local frontier deputy did not appear at the annual meetings or order that a replacement officer attended instead, such as happened at Sima during the 1925–1926 meeting, the Burmese authorities asked the Tengyue consul to petition the Chinese authorities.Footnote 39 The replacement of Chinese officials was of no small importance: those without frontier experience and rank were seen as less inclined to British interests, unable to take decisions on important matters, and therefore likely to leave more cases unresolved. Similarly, when the Chinese authorities initiated a request on adjustments to the rules for compensation and format changes to the meetings, the Tengyue consul relayed the proposals and took up the issue on behalf of Burmese officials, negotiating first-hand with his Chinese counterparts.

Second, consuls were negotiators. They offered advice to their Burmese counterparts on how to resolve cases and were tactful in court with Chinese officials. Advice on how to present cases could be ‘invaluable’ to the Burmese officers tasked with resolving as many cases as possible in the meeting.Footnote 40 The consul also helped smooth over differences of opinion and methods of adjudication between Chinese and Burmese officials. This skill and their ability to provide useful advice to their Burmese counterparts can be attributed to the consuls’ better understanding of Chinese methods and practices of adjudication and jurisprudence, which often appeared arbitrary, coercive, and retributive to Burmese officers.Footnote 41 Although resolutions were reached, annual meetings were often fractious. They were more akin to advocates trying to compromise with one another, rather than a presiding and deciding judge. This meant that tactful negotiators who were patient and persuasive were more likely to attain the resolution of cases that appeared a ‘success’ to the British authorities. An indication of this was relayed in the report of the 1914 meeting by the deputy commissioner of Myitkyina.Footnote 42 The case involved a Chinese defendant living on the British side of the frontier and therefore claimed as a British Burmese subject. The Burmese authorities took particular issue with the perceived uncompromising attitude of the Chinese deputy and the ‘bullying’ nature of his cross-examination of the defendant. The Tengyue consul, C. D. Smith, was asked by the Burmese authorities to protest against these methods on both their behalf and that of the Burmese defendant. These criticisms can be read not just as individual idiosyncrasies of the Chinese deputy, but perhaps as a reflection of the nature and custom of Chinese cross-examination, which sought a confession as a chief standard of evidence and pressed the defendant accordingly for an admission. Bridging this legal-cultural gap—and personal confrontations between Burmese and Chinese frontier officers—would have been a difficult task requiring a sensitive mediation technique. Although the details of how this was done are not recorded, this achievement was evident. At the next meeting it was remarked by the Burmese authorities that ‘the success of the Meeting as usual pivoted on the consul and it is solely due to Mr Smith's untiring patience and courtesy in rather difficult circumstances, and to his intimate acquaintance with [the] Chinese character and language that so many cases were settled’.Footnote 43

Consuls also thought strategically about how to present cases in ways that would be likely engender an outcome that was favourable to British interests. Theoretically the British and Chinese officers in court were two impartial judges endeavouring to reach a joint decision and common judgment. However, in practice, the two officials tended to act more like two barristers pleading their suits in a court without a judge, bargaining for a favourable outcome. Frequently, cases were carefully arranged to maximize the probability of compromise on both sides. As consul Hall noted,

if Burma has a sound case where it is felt that China ought to pay compensation, it is as well to place such a case immediately after a strong Chinese case where Burma has already paid, or decided that it will have to pay, compensation of at least an equal amount. Where China has a palpably weak case it is as well to slip in before it a weak Burma case which can, after a few minutes, be withdrawn as a generous gesture. Not infrequently the Chinese will reciprocate, yet without such a gesture they might have argued their case for hours and eventually sent it to the Court of Appeal. Nor are these more or less innocuous methods all. Tactics further demand acceptance of the distasteful curios shop procedure of prior over or under statement according as to whether one will receive, or will pay, compensation.Footnote 44

The consul was therefore skilful in his goal of resolving disputes, complying with a Chinese method of negotiation in order to settle cases.

Alongside communication and negotiation, the third role of the consuls was to attempt to strike up a personal relationship with Chinese officials to gain better leverage over them. This was essential as, despite the consuls’ linguistic skills and efforts towards cultural sensitivity, not all meetings ran smoothly. In 1915, for example, consul C. D. Smith protested that the Chinese authorities had failed to secure witnesses for cases and should therefore pay compensation for the omissions. He claimed that ‘with no inconsiderable heat, but in language in which there was no impropriety’, he had put across his point; nonetheless, the Chinese frontier deputy had called the consul Smith a ‘savage’ (yeman ren) and had sarcastically referred to him as being from ‘a [so-called] civilized country’ (wenming guo). Following the exchange, the meeting came to an abrupt halt.Footnote 45 The daotai had a different version of the events, stating that while they were ‘… amicably talking things over suddenly the Consul jumped up waving his fists and shouting. Chou Wei-Yuan [the frontier deputy] could not do otherwise than call him to order, and there was nothing improper in his doing so’.Footnote 46 Whereas this incident had stopped proceedings for the year, on the whole, the relationship between Tengyue consuls and Chinese officials was more cordial, and a personal relationship was vital to the resolution of cases. On reviewing the history of the meetings, Kunming consul-general Hall stated that ‘In the haggling, which takes place in these courts rather after the manner of a bazaar, only the British Consul has any influence with the Chinese, and that because he is known personally to them.’Footnote 47 Social events organized by the British frontier officers and consul after the meetings also helped build personal relations. These social events usually consisted of a dinner, marches, and various sporting activities. For example, in 1936, a military band consisting of Kachins dressed in kilts and playing the bagpipes accompanied the dinner at the frontier meeting at Nawngma.Footnote 48 Dressing the Kachins in kilts could be construed as a symbolic display of British power, but also pointed to the atmosphere of entertainment and festive occasion. The social gathering at the 1931 Sima meeting was considered ‘exceptionally successful’, with Chinese officials competing with the British officials in a rifle shooting competition, while ‘messrs. Carr [assistant superintendent of Sadon] and Liu [Liu Guoshu, administrative deputy of Chanta] entered together in a three-legged race against the Chinese, Indian and Kachin police and soldiers’.Footnote 49 In the 1921 meeting at Nawngma, ‘Chinese officials had paper crowns out of crackers at the official dinner and all pulled in a tug-of-war … whilst the Chanta deputy gave us a song … [and] … the Lungling Magistrate composed a poem on the spot to celebrate the occasion’.Footnote 50 Certainly, sports and performances were all part of the effort to engender a friendly relationship with the Chinese officials.

As well as the resolution of cases for the preservation of peace on the frontier and to maintain amicable Sino-British relations, consuls tactfully asserted and protected British sovereign claims to land, people, and resources in certain disputed areas. One of the most pertinent examples of the role of the consul as adviser, negotiator, and personable intermediary in cases were those arising in the region known as ‘Pi'enma’ (Pianma) to the Chinese and as ‘Hpimaw’ to the Burmese. Lying between the N'Maikha and Upper Salween rivers, it was a place described in the first decade of the twentieth century by Burmese authorities as an ‘unadministered’ region of the northeast part of the Myitkyina District. China claimed sovereignty over the region through a local fuyi further east, who had jurisdiction over the lands and paid allegiance to China. The British policy for the area was to assert that the boundary of the Sino-Burmese frontier was the river Salween rather than the N'Maikha river. After the fuyi attempted to collect tax on the Chinese authorities’ behalf, the British Burmese authorities decided to press forward with their claim to the disputed land. On sensing that the Yunnan provincial authorities had diminishing military power following the increasing political instability in Yunnan, the British Burmese military police occupied Pianma in 1910. The Chinese authorities protested, arguing that the boundary should be the N'Maikha, but they were powerless to stop the British occupation. As Britain refused to withdraw its claim, when cases arose over the disputed region, the Chinese authorities’ policy was to refuse to hear them in the frontier meetings as they did not regard them as ‘trans-frontier’. Outside the meetings, the Chinese authorities attempted to assert their sovereignty through legal claims arising in the region. For example, in the ‘Luktaw Housebreaking’ case in May 1916, it was alleged that a Chinese subject, who was temporarily residing in the jurisdiction of Burma, hired six ‘ruffians’—three from Burma and three from the Chinese territory—to tie up and beat an old enemy in the Htawgaw area.Footnote 51 British military police arrested the ringleader in the disputed territory. The daotai asked for his extradition, and in doing so, attempted to claim authority over the place where the crime took place. This was nevertheless rejected by the British frontier officer, demonstrating that the Burmese frontier officers were aware of the importance of legal cases for asserting claims to people, resources, or, indeed, land in the frontier.

The political sensitivity of disputes over territory in trans-frontier cases meant the Tengyue consul acted as a helping hand to the Burmese authorities to aid them in British sovereignty claims over Pianma even while deflecting political tensions. In 1917–1918, the Burma authorities decided to push for a resolution to three cases from the region. Eastes, the Tengyue consul, recognized the need to resolve the outstanding cases and speak to the Chinese officials in a way that preserved British sovereignty. On raising the possibility of hearing the cases at the next meeting, the consul reported that the Chinese authorities had renewed their claim against British sovereignty of the Pianma region. Two of the cases involved petty crime, but the third was of a more serious nature. It involved a party of villagers from the village of Chikgaw and its district, claimed by Burmese officials as their territory. The villagers went across the frontier to a market at Gutanhe (Ku-T'an-Ho) in China.Footnote 52 There, they were attacked, stoned, and robbed of property valued at Rs 96 by a band of seven or eight Lisu (‘Lisaw’) men, about two miles within the Chinese side of the Hpimaw pass. Eastes knew that the Chinese authorities would refuse to hear the cases, so he tactfully referred to common ground and international norms to try to convince the Chinese authorities to resolve the case. In his own words:

[I] talked the matter over with Mr. Chang [Chang Qiyin, Tengyue district magistrate and Appellate officer of Sima meeting] on the evening of his arrival at Sima, I put it to him that in all these cases certain persons had been wronged or injured by Chinese citizens hailing from what was indisputably Chinese territory, and that by universal law in every civilized country wrong-doers should be punished and innocent sufferers at their hands should have their wrongs as far as possible redressed.Footnote 53

Though Eastes persuaded the district magistrate to let the Chinese and British frontier officers hear the case, the Chinese frontier officers prevented it from being discussed at the frontier meeting. However, Eastes tried again, this time appealing to the daoyin, as the higher regional representative of the district of Tengyue offered a better chance of the case being heard. In fact, as the provincial officials in Kunming refused to entertain his petition, and given the devolved nature of political authority of Yunnan from the central Chinese government in Beijing, appealing to the daoyin was his only option. After pressing the issue with him, Eastes remarked:

… I decided to adopt different tactics. I therefore expressed my appreciation of his admission in previous similar cases of the duty of government to redress the wrongs of all victims of oppression, irrespective of their place of origin; and I requested the issue of strict orders to effect [sic] the arrest of the guilty parties and to afford compensation for the losses suffered by the complainants. This had the desired effect of staving off any fatuous repetition of the denial of the British status of Hpimaw and neighbourhood; Mr. Yu [Yu Renlong, Tengyue daoyin] replied five days later that he had issued orders to secure the arrest of the Lisaw gang of the strict enquiry into their conduct, and to deal with them; in accordance with the custom of the locality.Footnote 54

Although the question of sovereignty over Pianma was not settled—and, in fact, continued and intensified throughout the 1920s—Eastes found a temporary solution to the impasse created by the cases. He tactfully reinforced British sovereignty by circumventing the question of the occupation and thereby avoided damaging Sino-British relations. The handling of the case was careful; instead of asserting sovereignty claims, as pursued by Burmese officers in the meetings, Eastes appealed to the daoyin by using rhetoric that he felt would speak to Chinese notions of universal justice. Moreover, Eastes chose to raise the issue outside of the frontier meeting hearings, allowing for a less confrontational style in a more informal setting. The tactic was successful and set a precedent that was pursued by Eastes’ successor, J. B. Affleck. At the Nawngma meeting in 1920, Affleck sought an early interview with the Chinese official before the meeting and persuaded him agree to write to the local frontier deputy in Lushui to summon headmen of the village concerned and settle the case by arbitration.Footnote 55

From the consul's point of view, his role appeared important for negotiating with Chinese officials over trans-frontier cases. To the Burmese authorities, the consul's role of protecting and promoting their sovereign claims, maintaining an amicable relationship with the Chinese authorities, and helping to resolve cases was repeatedly emphasized as crucial to the successful resolution of outstanding cases and to the protection of British interests. In 1904, the Burmese authorities stated that they were ‘indebted for the cordial assistance’ of both the Kunming and Tengyue consuls for the resolution of cases.Footnote 56 In 1906, there was ‘amicable settlement’ of many pending cases, where the Tengyue consul ‘contributed not a little to the maintenance of harmonious relations’.Footnote 57 In 1909, 12 frontier cases were resolved at the first frontier meeting between Chinese authorities and Burma authorities of Myitkyina held at Sima. The Burmese authorities attributed the high number of resolutions and success in persuading the Chinese to police a valley associated with crime as ‘chiefly’ due to the efforts of the Tengyue consul Archibald Rose.Footnote 58 The success of consecutive meetings in the late 1910s and 1920s continued to be attributed by the Burmese authorities to the Tengyue consuls. H. A. Thornton, the superintendent of the Northern Shan States, noted at the 1919 meeting at Nawngma (when 58 cases were heard) that ‘the thanks of all British Officers are due to Mr A. E. Eastes for the ready assistance and unfailing courtesy which in five successive Meetings have contributed so largely to such success as has been obtained’.Footnote 59 A year later, the officiating superintendent of the Northern Shan States, Major E. Butterfield, was clear on the consul's role in both the meetings and appeal hearings, claiming that ‘too much credit cannot be awarded to Mr Affleck the consul, Têngyüeh for the patience and skills with which he assisted at the meetings of the Appellate Court and at all deliberations’.Footnote 60 Likewise at Sima in 1930, the Burmese official noted that ‘such success as has been attained is due to Mr Wyatt-Smith. A breakdown on the last day would have left several old and five new Santa [Chanta] cases untouched and this breakdown was averted only by the consul's tact and patience.’Footnote 61 Finally, in a review of the history of annual meetings, the Kunming consul-general, R. A. Hall noted that:

If no British consul from China were present at the Courts it would be likely to be a very serious disadvantage from Burma's point of view … All the reports from the Burma officers pay a high tribute to the work of the Consuls and the Consular clerk in producing friendly relations and helping to reach a solution, after a deadlock has been reached.Footnote 62

The consul was therefore a key mediator, and one whom the colonial Burmese authorities felt played a significant role in pursuing their aims both within the courts and outside of them, whether for the general resolution of cases, the maintenance of friendly Sino-British relations, or for promoting and protecting British Burmese sovereignty claims.

Conclusion

The stationing of consuls with legal powers in Yunnan ended with the Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights, which came into effect on 1 January 1943. This concluded the short, but nevertheless important, legal role of the Tengyue consuls in western Yunnan and on the Burma-China frontier. Consuls represented British subjects and mediated legal cases. Stationed on the fringes of the Chinese and British empires, their duty was closely tied to the Burma-China frontier where sovereignty claims arose and where they were the only person to represent British (and sometimes other foreign) subjects who required legal assistance or representation. Consuls were active outside of the consular courtroom, acting as a communicative intermediary and following up investigations of Sino-British cases. Although the role of the Tengyue consuls had much in common with other inland consuls, their frontier role marked them as distinctly different. On the Burma-China frontier, consuls worked as mediators in frontier meetings: as translators, advisers, petitioners, and as advocates for Burmese interests. Far from the treaty ports of the east coast, the Yunnan hills and valleys were not home to merely marginal consular outposts. This was also a place where consuls played an integral part in British trans-frontier governance, mediating key legal disputes between Burma and China, and helping to protect and buttress colonial Burmese authority.