Research on the history of Allahabad during the period of colonial modernity has tended to focus on either the anti-colonial nationalist politics championed by the Indian National Congress, or the status of the city as a centre of Hindi and the conservative Hindu nationalist movement.Footnote 1 This article draws attention to another defining aspect of the city’s identity: its significance as the site of a prolific and multilingual print culture that was shaped by the intertwined histories of political culture and the cultural politics of Allahabad, but also responded to these in ways that remain unexamined. Taking the Indian Press—established in 1884 and arguably the city’s most important multilingual publishing house—as a case study, I analyse the entanglements between print culture and debates on the contentious issues of languages and identities in a divided public sphere.Footnote 2 In so doing, I investigate the cultural trends prevalent in colonial Allahabad where liberal claims and aspirations of gaṅgā jamunī tahẓīb (the syncretic culture of the Indo-Gangetic plains) dwelled side-by-side with conservative norms, but were ultimately undercut.

My analysis also presents a fresh perspective on multilingualism as a cultural value during the period of colonial modernity. In a departure from the popular belief that mutlilingualism necessarily implies multiculturalism and tolerance of difference, I argue that the simultaneous thriving of several languages cannot be read simply as evidence that syncretism was the norm in the early decades of the twentieth century. During this period, many public intellectuals wrote and published journals in Hindi, English, Bengali, and Urdu. In the process, they shaped these languages as the vehicles of modernity and contributed to a flourishing multilingual public sphere in north India. Yet, the opinions promoted in some of these journals often pushed readers towards narrow cultural ideals. Thus, in mapping the print culture in the city, my article demonstrates a previously unexamined divergence between the trends in publishing and the opinions disseminated through journals. I demonstrate that while several publishers, most prominently the Indian Press, continued to invest in books in several scripts and languages yet Indian Press journals such as Saraswatī in Hindi, Prabāsī in Bengali, and The Modern Review in English, which dominated Allahabad and north India’s public sphere, vociferously advocated for Hindi as the national language and in general, pushed a Hindu majoritarian cultural vision. The Urdu Adīb was something of an exception as it proposed that Urdu could be the national language but also encouraged the coexistence of other languages and promoted multilingualism as a cosmopolitan civilizational ideal. Through a detailed reading of this complex field of cultural production of these journals over a period of several decades, I show that in the era of colonial modernity, while on the ground, publishers and presumably, readers, continued with their diverse reading practices, multilingualism as a core tenet of syncreticism was undermined by several prominent intellectuals. In explaining this divergence and mapping the decline of multilingualism, my article traces a major cultural shift in north India. I demonstrate that public discourse led by middle-classes and elite intellectuals was becoming increasingly homogeneous and insular, pushing a milieu of multilingual readers and publishers towards conservative ideals.

The article is divided into two parts. The first sketches out the divisions within the public sphere in colonial Allahabad. The efforts of Madan Mohan Malviya and other cultural leaders ensured that Hindi-Hindu nationalism thrived in the city under the auspices of the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan and the provincial Hindu Mahasabha. Even while the activities of Malviya and others gained ground, I show through my examination of the history of publishing in Allahabad (with a special focus on the period between 1890 and 1920 when the Indian Press was at its peak), that a number of presses continued to publish in more than one language and script until the end of the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, the number of Hindi Presses were slowly increasing in number and Indian Press remained the most committed multilingual publisher of the city. Against this background, the second part examines the history of the Indian Press and its enterprising founder, Chintamoni Ghosh. In the absence of personal correspondence or publishers’ records, I reconstruct the press and its owner’s intellectual and socio-cultural commitments by collating data from colonial records and pages of the journals printed or published by the Indian Press. Finally, I analyse the rich archive of public discourse which appeared in four of the most prominent general interest journals that this press produced as either a printer or publisher: Saraswatī in Hindi, Prabāsī in Bengali, The Modern Review in English, and Adīb in Urdu. These journals provide an unparalleled insight into the complex cultural trends of the city that take us beyond publishing data.

A caveat is important here. My article does not engage with the reception history of the four journals but rather, looks at their role in opinion building. In addition, this article is by no means an exhaustive analysis of the journals, three of which have received some scholarly attention.Footnote 3 Rather, I reconstruct the history of the Indian Press and adapt a comparative multilingual method that focuses on a discourse analysis of the four journals. The aim is to present an overview of the general cultural politics of these journals to reveal the divided nature of the public sphere in colonial north India. Each journal catered to a different linguistic group and attempted to shape public opinion, especially on the contentious issues of language and identity. Consequently, a monolingual focus would only provide access to the opinions of some sections of the reading public and not a wide cross-section of the city, thereby obscuring the contestations that I highlight here.

A divided public sphere

Multilingualism in the colonial provincial capital

A number of scholars have drawn attention to the practice of multilingualism in the era of colonial modernity in India. For instance, Ulrike Stark’s work focuses on the multilingual publications of the Naval Kishore Press of Lucknow in the nineteenth century, Francesca Orsini discusses the multilingual publishing phenomenon of popular and commercial works which she calls ‘texts of pleasure’, and Rochelle Pinto examines the Konkani, Marathi, and Portuguese print and political cultures of Goa.Footnote 4

Similarly, multilingualism in the early modern period, especially, its prevalence in courtly milieus has been extensively discussed. Exploring the various instantiations of multilingualism in north India, Orsini suggests that adopting a multilingual perspective means ‘taking a circumstantial and historicized approach to multilingualism that rejects the opposite poles of claiming that mixing languages and tastes was the cultural norm (“composite culture”) and surprise at any instance of mixing of Perso–Urdu and Hindi demotic or Sanskritic traditions’.Footnote 5 Thibaut d’Hubert’s work depicts the flourishing of a ‘multilingual adab (Islamicate cultural ethos)’ at the court of the coastal kingdom of Arakan in the seventeenth century, best exemplified in the works of the poet alaol.Footnote 6 I contribute to this growing field through my case study of Allahabad and the Indian Press. In particular, my discussion highlights the fate of significance and the limits of multilingualism as a cultural value in the period of colonial modernity after avenues of court patronage had dried up and at a time when literary cultures had to contend with the conditions of print capitalism and contentious cultural politics that were shaping the discourse on languages.

Multilingualism had flourished in Allahabad since the sixteenth century after the Mughal Emperor Akbar made the city capital of his newly established ṣubah (province). The presence of the governor’s (subedār) court in the city ensured that Persian—then a significant cosmopolitan language of the Indo-Islamic world, and the main medium of administration and literary expression —found patronage. The city’s cultural growth could also be attributed in large part to the arrival of Sufis who went on to establish 12 prominent dāʼiras (circles, centres) in Allahabad. From the eighteenth century onwards, Rekhta/Urdu poetry developed. With the arrival of the East India Company, Urdu received a further boost when it became the administrative language of the region, replacing Persian in 1837.Footnote 7 Beginning in the nineteenth century, the influx of many migrants from neighbouring mofussils and qaṣbas (towns) as well as from other regions of India brought Bengali, Kashmiri, Kumaoni, and other languages to Allahabad, changing the linguistic landscape and increasing the diversity of its inhabitants. The presence of a significant number of professional migrants who were interested in opinion-building activities and participation in public discourse had a major impact on book publishing and journalism. Allahabad’s literate classes were largely comprised of these professional migrants and locals drawn from mercantile and scribal castes such as the Kayasthas, Khatris, Agarwals, and Kashmiri Brahmins.Footnote 8 Contrary to what Christopher Bayly suggests in his work on Allahabadi politics, the socio-political investment and range of intellectual opinions among this group was not exhausted by their participation in anti-colonial nationalist activities. Furthermore, economic motivations do not sufficiently explain the interest of the Allahabadi corporate elites in politics.Footnote 9 Rather, as my discussion here demonstrates, they were keen to shape the cultural discourse on identarian issues that was emerging in the public sphere. It was this investment in determining public opinion that led several Allahabadis to write and publish, becoming agents in the world of words and texts. As a result, some Allahabadis were engaged in stridently championing the cause of Hindi in public discourse, such as the prominent nationalist leaders Madan Mohan Malviya and Purushottam Das Tandon. Meanwhile publishers, such as the Indian Press among others, continued to publish in a variety of languages, including Urdu. In scrutinizing the socio-political trends in all the major languages prevalent in the city, I show that both these aspects—the conservative and liberal instincts, simultaneously remained in a state of tense contestation in the public sphere of Allahabad of the late nineteenth and early twentietch century.

The Hindi-Hindu Camp and the Effects on Multilingualism in Allahabad

Under conditions of colonial modernity, multilingualism of the pre-colonial variety experienced a steady decline in practice as well as in cultural value. For instance, Braj Bhasha and Awadhi, traditional literary registers of the region were waning and set aside by the incessant fracturing of Hindi and Urdu into two different languages.Footnote 10 Scripts such as Kaithi and Mahajani were also side-lined by the dominance of Nagari.Footnote 11 This loss of linguistic diversity in north India was a direct result of what came to be known as the Hindi-Urdu controversy, a ground-altering, decades-long conflict between the Hindi and Urdu languages and their counterpart scripts, Nagari and Perso-Arabic.Footnote 12

Madan Mohan Malviya, the Hindi publicist and Hindu nationalist leader, and other prominent Allahabadis like him, were often active in both Hindi literary-cultural networks as well as right-wing politics in Allahabad.Footnote 13 In 1900, in response to an extended campaign led by Malviya, who compiled a crucial memorandum entitled Court Character and Primary Education in the N. W. Provinces and Oudh,Footnote 14 a landmark ruling was passed by the provincial Lieutenant Governor, Antony MacDonnell, granting Nagari and Perso-Arabic equal status for administrative and judicial purposes in the North-Western Provinces. Alok Rai refers to this momentous decision as the ‘MacDonnell moment’.Footnote 15 Malviya played a leading role in shaping the course of events and it was largely due to his initiatives that the cause of Hindi language and Hindu nationalism became twin causes in Allahabad.

In the wake of the 1900 ruling, the next step in the consolidation of Hindi as the dominant language of cultural expression in the region came with the establishment of the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan (Hindi Literary Association). The Nagari Pracharini Sabha (Organisation for the Promotion of Nagari, established 1893) of Banaras, the foremost formal platform for the promotion of the language-script, passed a resolution on 1 May 1910 proposing the establishment of an institution that would function as an umbrella organisation for all bodies involved in the promotion of Hindi.Footnote 16 The first session of the Sammelan was held in Banaras in the same year on 10 October 1910, presided over by Malviya who delivered the keynote speech.Footnote 17 The second session was held in Allahabad in 1911 and it was decided that the institution would have its permanent home there. Purushottam Das Tandon, also an Allahabadi citizen and a staunch advocate of Hindi, played an important role in ensuring that the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan stayed in Allahabad.Footnote 18

In this regard, the close association between the Indian National Congress and the Mahasabha at the turn of the century is also worth noting. Malviya continued to actively champion the cause of Hindi and the activities of the Hindu Mahasabha in Allahabad. In fact, the formal move to establish an All-India Hindu Sabha was made at the annual session of the Indian National Congress held in Allahabad in 1910. This initiative failed but the Hindu Mahasabha was formed five years later, on 13 February 1915, in Haridwar, with Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in attendance. Meanwhile, the uneasy relationship between one faction of the Congress and the Hindu movement continued until the Mahasabha emerged as a separate organisation under the leadership of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, and there was a decisive break between the Congress and Mahasabha in 1926.Footnote 19 These developments demonstrate two notable aspects of the movement in Allahabad: that the Hindi language lobby had a small but strong urban base among the social elite, and that to a large extent, they found a favourable breeding ground among the Hindu professional classes. As result, the last decades of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth witnessed the formation of Hindi-Hindu nexus in Allahabad led by Malviya.

Trends in the print culture of Allahabad: Multilingual publishers and journals

How were these trends reflected in the city’s textual and journalistic culture, which were related to the political domain but also maintained a certain degree of distinction and autonomy? Christopher King’s analysis of publishing figures for the cities of the North-Western Provinces shows that between 1868 and 1925, Allahabad published more books in Hindi than in Urdu, with a steady decline in the share of Urdu over the years. To cite one set of statistics, in 1900 63 per cent of the publications were in Hindi and 15.7 per cent were in Urdu.Footnote 20 However, Ulrike Stark cautions against drawing conclusions about the domination of Hindi texts based on King’s otherwise comprehensive and informative data. She states that due to lack of information on the particulars of publications, educational and non-educational titles were not segregated in this data set, nor were reprints separated from originals. The higher numbers for Hindi titles could reflect the large number of Hindi textbooks published by commercial publishing houses under lucrative government contracts.Footnote 21 Stark argues that the data are especially fluid when original titles in Hindi and Urdu are taken into consideration. For instance, she shows that 560 Urdu titles were registered in the North-Western Provinces during the year 1895, compared with 354 in Hindi. These figures do not quite support the proposition of Hindi dominance in the region.Footnote 22 Furthermore, if we follow King in focusing only on statistics and the tussle between ‘Hindu-heritage’ and ‘Muslim-heritage’ languages, we overlook the other languages of Allahabad, such as Bengali and English which also featured in the public sphere.Footnote 23 My analysis of the print culture in the city with a focus on Indian Press’s publication history takes this analysis one step further and complicates the portrait. While some multilingual publishers continued to publish in many languages, the number of Hindi presses also grew after 1900. The fractures, in fact, showed up more clearly in cultural discourse and rhetoric than in publishing figures. It is here that turning to the content of the journals that shaped public opinions plays an illuminating role.

From the 1840s onwards, several developments took place in Allahabad’s print culture; in chronological order, these were: the establishment of the Allahabad Presbyterian Mission Press in 1840, the shift of the Government Press to Allahabad in 1858, and the emergence of private printing and publishing firms from the 1860s onwards.Footnote 24 These milestones transformed Allahabad into a major publishing hub. Publishers’ catalogues and records from this period have not been preserved. Consequently, Quarterly Lists—records created by the colonial government in order to regulate, control, and censor publications— despite their various shortcomings—are the best sources for an overview of the Indian publishing market in this period.Footnote 25

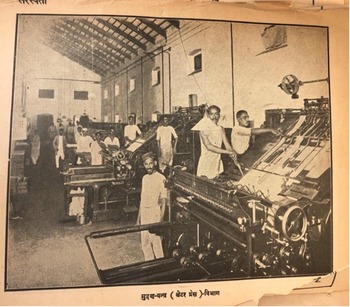

My examination of nearly 60 years of publishing data on Allahabad shows that around 1900, there were nearly 40 presses active in the city. Some catered to a specific linguistic audience. For instance, among the English presses, the Pioneer Press (established in 1864) functioned as the voice of the European population in Allahabad and published only English-language titles. It also published the foremost English newspaper of the region, The Pioneer. The Queen’s Press and Vidya Dharma Vardhak only published in Hindi. Urdu publishing continued to flourish in the city with both publishers and writers representing various religious communities. As Table 1 charting bilingual and multilingual publishers shows, several presses published in two or more languages, though some were far more prolific and prominent. It was not unusual for Hindi presses to publish in Sanskrit, or presses which published in Urdu to publish in Persian and Arabic. Several presses that published in the Perso-Arabic script were owned by Hindus, such as Zubdat-un-Nazair by Awadh Bihari Lala and Star Press by K. C. Bhalla.

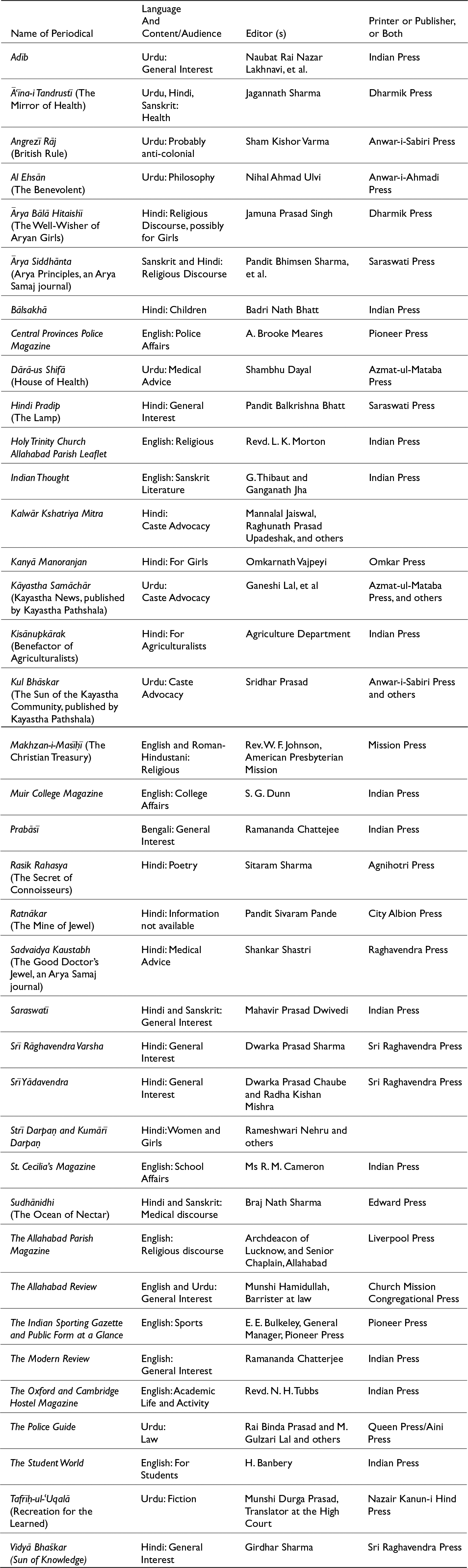

Table 1: Some Bilingual and Multilingual Publishers of Allahabad, 1890–1920

Source: Compiled on the basis of Quarterly list of publications, United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, 1890–1920.

However, there were only a handful of presses which invested in languages across the divide of scripts and languages and were truly multilingual. Apart from the Indian Press, these were: Allahabad Press run by Sen and Co., National Press by Ramzan Ali Shah, Nazair-i-Qanun Press by Keshav Chandra and later N. B. Mathur, Star Press by K. C. Bhalla, and Naval Kishore Press of Lucknow which maintained a branch in Allahabad. The missionary organizations were also part of this multilingual trend. The North Indian Christian Tract and Book Society, North Indian Bible Society, and Christian Literary Society all ran their own presses, as did the Allahabad Presbyterian Mission Press and the Indian Christian Press. They adopted the approach of publishing educational as well as religious titles in many languages in order to reach a wide variety of socio-linguistic audiences who also held varying degrees of literacy.

After 1900 and the MacDonnell moment, many new Hindi language presses opened such as Mishra Press and Sudarshan Press; or some, such as Standard Press, published in both the two new languages of the market, Hindi and English. Meanwhile, smaller presses such as Exchange Press, Namwar Press, Nisar Press, and Satyahitaishi Press which had thrived in the 1890s by publishing in Urdu and at least another language, disappear from the records after 1900, suggesting that they had folded up.

Table 2 shows that Allahabad was also one of the foremost centres in the publication of periodicals. Between 1890 and 1920, there were approximately 40 periodicals in the city that published in the various languages of the region.Footnote 26 Several were published by book publishing houses which shows that investing simultaneously in books and periodicals seems to have been a rewarding commercial strategy, as is borne out by the case of the Indian Press which I discuss in the next section.

Table 2: Periodicals Published in Allahabad between 1890 and 1920

Source: Compiled on the basis of Quarterly list of publications, United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, 1890 –1920 and available copies of journals.

Alongside the publication of texts, a vibrant culture of journal publication, especially in Urdu and Hindi, thrived in the North-Western Provinces with Allahabad again playing a leading role. Maḵẖzan-i Masīḥī (founded 1868) was one of the first journals published in the city in any language and possibly the first Urdu journal. Under the editorship of Rev. W. F. Johnson of the American Presbyterian Mission, it went on to become one of the foremost Christian publications in the region. In the 1890s, the journal was published by the Mission Press, a pioneer in the use of the Hindustani-Roman script.Footnote 27 The Allahabad Review (established 1890), a general-interest bilingual journal which carried articles in Urdu and English, was edited by a barrister, Hamidullah Khan, who was evidently proficient in both languages. The articles were not translations: the Urdu and English sections published separate content but both focused on poetry, philosophy, contemporary affairs, and local concerns. Āʿīna-i Tandrustī (date of establishment not available), edited by Jagannath Sharma, focused on health and was trilingual (Urdu, Hindi, and Sanskrit) and its editors and publishers were Hindu. In fact, the editors of many Urdu journals such as Angrezī Rāj, Dārā-us Shifā, Kāyastha Samāchār, Kul Bhāskar, Tafrīḥ-ul-ʿUqalā, and The Police Guide were identifiably Hindu.

Banaras is renowned as the seat of famed Hindi journals with Bharatendu Harishchandra’s Kavivachansudhā (1868–1885) and Harishchandra’s Magazine (1873–1885, initially a Hindi journal with some English language content, later renamed Harishchandrikā), as the two pioneers in the field. But Allahabad was not far behind. Two Hindi periodicals, Vrittānt Darpaṇ and Prayāg Dūt, were launched in Allahabad in 1868 and 1871, respectively.Footnote 28 The first Hindi journal to attract a significant readership in Allahabad was Pandit Balkrishna Bhatt’s Hindī Pradīp (1877–1910), followed by Pratapnarayan Mishra’s Brāhmaṇ (1883–1895).Footnote 29 Both were vociferous advocates of the Hindi-Nagari campaign. Publishing in Hindi, including translation from Sanskrit, was in line with Bhatt’s politico-cultural ideology and promoted the beliefs that Sanskrit and Hindi in the Nagari script were the true representatives of the cultural heritage of north India.Footnote 30

This brief overview of publishing houses and journals in Allahabad demonstrates that despite the strident steps taken by the Hindi campaign, many languages co-existed, competed, and thrived to some degree even in the early decades of the twentieth century. Older cosmopolitan languages like Persian and Sanskrit survived but publications in the literary registers of the pre-colonial period such as Braj Bhasha and Awadhi were few and far between. But English, Urdu, Hindi, and other modern languages continued to be used simultaneously by a wide user base despite the controversies surrounding Hindi and Urdu. It is noteworthy that even in the 1890s, as the names and identities of authors and publishers in Tables 1 and 2 show, the presses showed no marked preference for Urdu or Hindi, Perso-Arabic or Nagari. A fair number of users from different religious backgrounds employed Urdu for literary, pedagogical, religious, and quotidian purposes. Consequently, publishing figures suggest that at least in pockets, publishers and readers continued to be multilingual.

However, in order to examine the fractures within multilingualism that were visible in the divergence between publishing figures and elite cultural discourse, we turn to the history of the Indian Press, in particular its journals. While the Indian Press continued to invest in books in all the languages prevalent in the region and produced journals in four languages between 1900 and 1915, the opinions expressed in the journals mirror the divided nature of the public sphere.

The Indian Press and its world of journals

The rise of the Indian Press under Chintamoni Ghosh

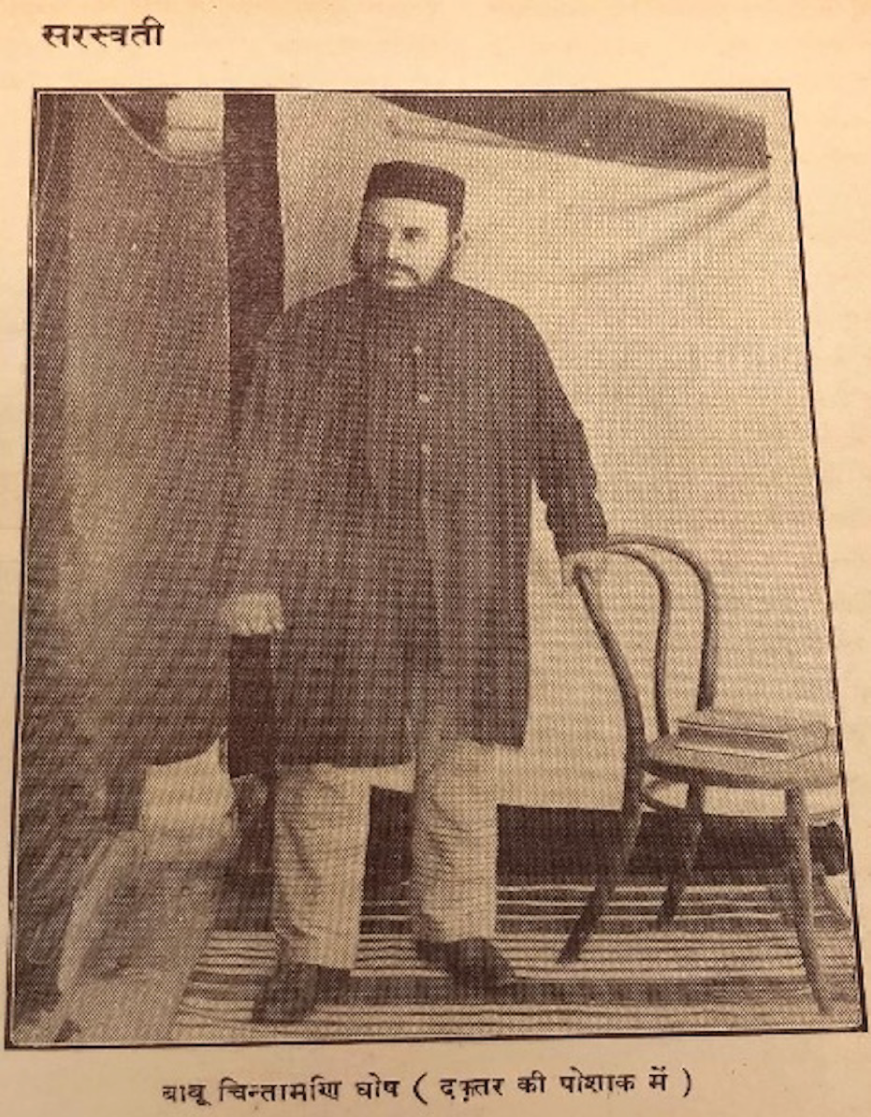

The rise of the Indian Press occurred against the background of the shifting socio-political and linguistic situation that I outline above. It was established in 1884 by Chintamoni Ghosh (1854–1928), a print capitalist whose life is a classic rags-to-riches tale (see Figure 1). His father had migrated from the Hooghly district of Bengal to take up a clerical job in the administration of the North-Western Provinces possibly around the early 1860s.Footnote 31 Orphaned at the age of 10, Ghosh received no formal education beyond middle school. Consequently, his life trajectory differed significantly from that of the elite migrants mentioned earlier. In contrast with other men of letters, Ghosh was a self-taught entrepreneur who was first exposed to the world of print as a 13-year-old apprentice in the offices of the Pioneer Press, where he worked on a monthly salary of 10 rupees, a meagre amount even by the standards of those times.Footnote 32 As the son of migrants, Ghosh essentially grew up bilingual and matured into a multilingual intellectual. His natural talents were possibly encouraged by the environment in which he found himself: Ghosh learned English while he was employed at the Pioneer Press by reading the Pioneer, the press’s hallmark publication and Allahabad’s leading English-language newspaper which had once employed Rudyard Kipling. Given his association with the Urdu journal, Adīb, it is likely that he learned Urdu at some point.Footnote 33 His next job was as a clerk in the Meteorological Department. As a young man in his 20s and in collaboration with a friend, Ghosh used his small savings of Rs 250 to establish a new publishing house in a humble building on Kachhari Road.Footnote 34 After that building was destroyed in a fire, the press moved to the neighbourhood of Katra, by which time Ghosh had bought over his friend’s investment in their business. The growing success of the press was in fact mirrored in the subsequent shifts of premises. By the 1910s, the Indian Press occupied an impressive building at 3, Pioneer Road (see Figure 2).Footnote 35 At the time of his death in 1928, Ghosh had built up one of the province’s finest publishing houses, an intellectual powerhouse in the city’s cultural landscape.Footnote 36

Figure 1. Chintamoni Ghosh, founder of the Indian Press as a young man, 1928.

Figure 2. The Indian Press, 3 Pioneer Road, Allahabad, 1928.

In tracing the history of the Indian Press, it is noticeable that it inherited Allahabad’s multilingual milieu and in return, left its own distinct signature upon the city. The press flourished by publishing in both English and vernacular languages, which were emerging in this period as the languages of the market, of creative expression, social life, and political affairs. Meanwhile, even though Persian was fading in popularity, the press decided to continue publishing in this language. Nothing remains of the Indian Press’s records,Footnote 37 but a special issue of Saraswatī titled ‘Śrāddhaṅka’ (obituary issue) published in September 1928 following Ghosh’s death in August, functions as an important archive of the history of the Press and its proprietor’s life, as well as the textual and journalistic culture of Allahabad. The articles and photographs included in this special issue, along with the journals of the Indian Press and records available in the Quarterly List, give a sense of his legacy but paint a partial picture by only emphasizing the association with Hindi.

Among its many notable features, ‘Śrāddhaṅka’ carried photographs of writers, editors, and intellectuals associated with Ghosh and the Indian Press. These portraits of eminent Allahabadis furnish a glimpse into the city’s hall of literary and political fame, including Ganganath Jha (scholar and Vice-Chancellor), Ramananda Chatterjee (journalist), Sir Sundarlal Dave (lawyer), and Major Baman Das Basu (military officer and author), among others. They also provide an overview of the network of intellectuals who had contributed to the press’s success. The existence of such a network explains to some degree why a cultural site like the Indian Press was able to flourish in Allahabad more than in any other city as there was a ready pool of multilingual talent that was easy to draw upon. Relying on this eclectic mix of migrants and locals, top-notch politicians and ordinary people, intellectuals as well as professionals employed in the city who had coalesced around some key institutions such as the administration of the North-Western Provinces, the High Court, and the University, the Indian Press emerged as the leading publisher of the region.

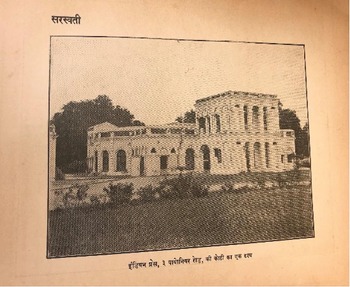

The ‘Śrāddhaṅka’ also featured photographs of the pressroom, machinery, and workers who fuelled this efflorescence in print (Figure 3). The visual evidence combined with the articles demonstrate that the press envisioned itself as a modern, corporate firm with regional branches and a large-scale industrial operation. For instance, the press created a wide distribution network beyond Allahabad by establishing an office in Banaras and outside the North-Western Provinces in Calcutta. Photographs titled ‘The Power-House’, ‘Hindi and English Composing Division’, ‘Letter Press Division’, ‘The Offset Machine Division’, ‘Linotype Division’, and ‘Lithography Division’ attest to an expanding and efficiently run business enterprise. The articles in the special issue narrate how the press built a reputation for itself not just based on its sophisticated content but also for its excellence in producing fine artefacts by focusing on the quality of paper, ink, and even typefaces. In fact, the Indian Press was one of the earliest publishers to publish impressive photographs and colour images of artwork by important contemporary artists in the pages of its journals. The existence of departments like the ‘Camera Division’, ‘Photo Etching Division’, and ‘Fine Arts Division’ are further testimony to how seriously the press regarded its aesthetic role as a purveyor of art. The storage, distribution, and sale of printed items were handled by the ‘Godown Division’ and ‘Book Depot Division’. There was even a post office on the premises.Footnote 38 Taken together, these photographs provide a rare behind-the-scenes portrait of the daily operations of an Indian printing and publishing house in the early decades of the twentieth century. They also establish the fact that within 40 years, Chintamoni Ghosh had built up another ‘empire of books’.Footnote 39

Figure 3. View from inside the Indian Press, 1928—the Letter Press Section.

These obituaries and photographs memorializing the Indian Press and Ghosh appeared in the Hindi journal, Saraswatī, which followed a specific Hindi-centric agenda that I discuss below. As a result, the connection between Ghosh, the Indian Press, and the Hindi language is the only aspect of publishing history highlighted in this source, with almost no mention of their contribution to other languages. In contrast, a sample of the non-Hindi titles of the Indian Press extrapolated from the Quarterly List and presented here shows that the range of publications went far beyond this limited monolingual portrayal. For example, within a sample period of just five years between 1894 and 1899, the Indian Press published and printed some 75 titles in languages other than Hindi, with several titles in Urdu and some in Persian. The mention in the list of Kumaoni, Gujarati, Arabic, and German book titles, all of which could be printed using typefaces already available for Nagari, Perso-Arabic, and Roman scripts, could possibly indicate another interesting phenomenon. It is possible that the demands of the market and the ready availability of technology allowed a profit-minded entrepreneur to venture into publication in these languages too, albeit in a limited way. The richness of the Indian Press’s multilingual book list and the institution’s phenomenal success were surely connected; a multilingual repertoire and investment in diversity made good commercial sense.

Thus far, I have demonstrated that the Indian Press and its entrepreneurial proprietor, Chintamoni Ghosh, operated much like the print capitalist of Lucknow, Naval Kishore, in not taking sides with any linguistic or political camp but adapting according to the direction in which the market was moving. As a result, the Indian Press’s book list reflects the multilingual tastes of the demographic constituents of the city and its intellectual life. But the opinions disseminated by the journals of the Indian Press shore up a more conservative facet of the city’s public sphere and complicates our understanding of multilingual practices in Allahabad.

Divergence of opinions among the journals of the Indian Press, 1900–1920

The Indian Press ventured into journal publication a few years after its establishment in 1884. It printed the short-lived Allahabad Review, a bilingual Urdu-English periodical which was edited and published by Hamidullah Khan from 1890 until possibly 1894. It was only from 1900 onwards that the Indian Press decided to invest heavily in journals, functioning as the printer for several journals and as both printer and publisher for a few (see Table 2). These journals contributed in no small measure to its reputation as a serious and highbrow publishing house. In chronological order of appearance, the general interest journals produced (i.e., either published or printed) by the Indian Press in the first two decades of the twentieth century that I discuss here are: Saraswatī (Hindi, 1900); Prabāsī (Bengali, 1901); The Modern Review (English, 1907); Adīb (Urdu, 1909/1910).

Unlike textbook publication, journals were not always profitable ventures and often had to be bankrolled by publishers in the initial years.Footnote 40 In the absence of any personal correspondence, diaries or publications by Ghosh—an ironic situation for an agent of print—it is not possible to definitively pin down the motivations for his heavy investment in the world of journals, but the fact that he adopted a similar multilingual publishing strategy for books reflects that probably in the long term, periodicals were sound commercial investments. In addition, Ghosh was likely interested in intervening in the public discourse by establishing the Indian Press not just as a competent press but rather, as an intellectually vibrant institution.

By promoting a number of journals, the Indian Press created a formal discursive space in Allahabad for the discussion of current socio-political ideas. An analysis of the cultural policies of four general-interest journals in four languages gives us an insight that goes further than the history of the press. Read in this way, the journals function as a crucial archive and documentation of the cultural contestations that characterized the public sphere in Allahabad.Footnote 41 In my examination of the journals in this article, the focus is on the content (including the genres and scope of articles), the editors and editorial policy, and the ideological inclinations reflected in the pages especially on the fraught issues of language policy and culture. The decision by the Indian Press to publish journals coincided with a crucial shift in the linguistic and socio-political history of the North-Western Provinces—the arrival of Hindi as the language of primary education and administration as a result of the sustained campaign that I discuss above. Therefore, the four journals, with their differing ideologies, marked important moments of intervention in this debate and on the larger question of cultural identity that was germane to the issue, whether it would be Hindi and a Hindu cultural vision that would define the nascent nation, or a syncretic, cosmopolitan ideal that would accommodate all linguistic and religious identities.

Saraswatī

The Indian Press created a firm foothold in the world of journals at the beginning of the twentieth century with the inauguration of Saraswatī in 1900, which went on to become the foremost Hindi journal in the country. Ghosh’s decision to invest in a Hindi journal before journals in any other language indicates that he had observed the success of previous Hindi periodicals and astutely gauged the increasing popularity of Hindi in north India. To a large extent, the journal’s success depended on Ghosh’s connections with the network of Hindi litterateurs and publicists in the city and region. For example, it was initially edited by Babu Shyam Sundar Das (ed. 1900–1902), the founding secretary of the Nagari Pracharini Sabha of Banaras—the foremost organization for the promotion of Hindi language and Nagari script in the region. Two years later, the editorship was passed down to Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi on Das’s recommendation.Footnote 42 Dwivedi steered Saraswatī for the next 20 years (1903–1920). In the early years of publication, Saraswatī published between five and eight articles covering about 35 pages per issue, which gradually increased to about 40–50 pages by 1905.Footnote 43 The elevation of Hindi/Nagari to official status in 1900 had a robust effect leading to an increase in readers. For instance, initially, Saraswatī had a modest circulation of 600; by 1911 it had increased substantially to 1700.Footnote 44

During this time, Dwivedi shaped both the journal and through it, the Hindi literary scene. Before taking over as the editor of Saraswatī, he had already published several authoritative works on the history of Hindi literature and translated Sanskrit classics for the Indian Press. Through his close association with the Press and Saraswatī, Dwivedi rose to the highest echelons of the Hindi literary establishment. So powerful was his influence that the early years of the twentieth century were subsequently classified by Hindi scholars as the ‘Dwivedi Yuga’ (Dwivedi era). Thanks to the efforts of Dwivedi and Saraswatī, the Hindi language and Nagari script achieved success on the regional stage and emerged as the prime contenders for the status of ‘national’ language. Mody comments on the seminal role Dwivedi played in cementing the future of Hindi:

In 1900 then, the very idea of a “Hindi literature” was still in the process of radical transformation. Its political import as a means of laying claim to a modern, national identity was just gaining ground and its conceptual boundaries were as yet un-theorized in public discourse. Though Harishchandra had undoubtedly initiated the process, Hindi literature would emerge as a modern category with clearly defined boundaries only after the turn of the century, in the period between 1900 and 1920.Footnote 45

Furthermore, Dwivedi ensured that only one register, Khari Boli, ‘the upright tongue’, could pass muster as modern Hindi. Allison Busch writes in this regard: ‘He implemented a draconian editorial policy for Saraswatī magazine, accepting only Khari Boli poetry submissions. He generally frowned upon dialectical variants, promoting a new kind of standardized, and frequently Sanskritized Hindi.’Footnote 46 The vicious tone adopted by Saraswatī’on the matter of languages is further visible in a series of well-known caricatures on the Hindi-Urdu controversy published by the journal which depicted Hindi as a chaste, elderly lady harangued by Urdu, portrayed as a beautiful harlot and an immoral upstart.Footnote 47 This straitjacketing of Hindi under nationalist conventions was also reflected in the narrow base of authors, most of whom were drawn from the upper-caste Hindu-Hindi male establishment of the city. The names of only one or two women appeared as contributors in the early years, and even then, at least one wrote under a pseudonym—‘Ek Baṅgamahilā’ (A Bengali Lady).

For our purposes, two important shifts were brought about by the success of Saraswatī. One is summarized in Orsini’s observation that Saraswatī emerged as the first ‘commercially viable miscellaneous journal’ in Hindi and ‘helped move the center of Hindi journalism from Calcutta to the United Provinces’.Footnote 48 Second, after the ascent of Hindi in this region, the language moved forward with its attempts to claim the spot as the national language. From the time of Saraswatī’s establishment, Dwivedi and the journal were closely aligned with the Khari Boli Hindi project and played a seminal role in the campaign to establish Hindi as the representative language of north India, and subsequently, of the nation. It was through its association with Saraswatī that the Indian Press, together with the city of Allahabad, gained a reputation as the centre of a nationalist, authoritarian version of modern Hindi. However, this portrait of the press and the city becomes complicated when Saraswatī is viewed alongside the other journals produced by the Indian Press.

Prabāsī

In 1901, one year after the launch of Saraswatī, the Indian Press and Ghosh collaborated with Ramananda Chatterjee (1865–1943) to publish Prabāsī, a periodical for the Bengali community in Allahabad. Bengalis were one of the earliest communities to migrate to the North-Western Provinces after the colonial administration moved to Allahabad, creating new jobs. As an educated and professional community, they were a significant and powerful presence.Footnote 49 Chatterjee himself had moved from Calcutta to Allahabad in 1895 to become Principal of the Kayastha Pathshala Intermediate College, run by the powerful Kayastha community. Existing scholarship on Prabāsī has highlighted how the journal was crucial for the formation and consolidation of a middle-class bhadralok (literally, genteel folk, gentlemen, civilized people) nationalist identity within Bengal in the twentieth century.Footnote 50 By paying attention to the nascent, formative stage of Prabāsī in north India, this discussion highlights an unexamined aspect of the journal. Viewed from the prism of its origins outside Bengal, I show that Prabāsī represents one of the earliest instances of the discursive formation of a migrant regional identity.

The title of the journal, Prabāsī translates as ‘one who lives outside of one’s home’. The word Prabāsī (Hindi, pravāsī) also implies that such a person maintains a connection with their homeland.Footnote 51 The journal emphasized both these experiential aspects from the very outset. Today, Prabāsī bāṅgālī is the common term for any Bengali who lives away from Bengal. By giving voice to the experience of Prabāsī life, the journal and the coinage borrowed from each other and reified the concept further in the public imagination. Many of the contributors were from the migrant Bengali community of Allahabad and neighbouring cities of the North-Western Provinces and wrote about their experiences. At the same time, the journal published poems, articles, and advertisements from Bengal which provided an important connection to the ‘homeland’ left behind and brought the public sphere of home closer to the migrant. Alongside Prabāsī authors, the list of contributors featured many well-known intellectuals from Bengal.

In its first year, Prabāsī comprised an average of 38 pages per month, totalling 466 pages per year.Footnote 52 Discussion of the migrant condition was distributed across many genres such as poetry, prose, and satire. In fact, the genres seemingly performed an affective division of labour, wherein poetry was the medium of choice for expressing the affective facets of the migrant’s experiences while prose was used to explore the socio-cultural and political aspects. For instance, the inaugural issue of the journal featured a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, also titled ‘Prabāsī’. The poem speaks in the first-person, self-reflective voice of a migrant addressing himself and emphasizes a liberal humanistic view of placelessness, not as dislocation but as a cosmopolitan celebration of being at home in the universe. The poet’s advocacy of humanistic universalism over narrow nationalism became more pronounced over time and is reflected in this poem. Quotidian concerns of the migrant Bengali community found expression in prose columns such as ‘Bengalis Outside Bengal’ (Bonger Bāhire Bāngālī) and a satirical column—‘Kamalakanta in Prayag [Allahabad]’ (Proyāge Komolākānto)—presumably written by the editor in his guise as a well-known fictional character from Bengali literature. One of the recurring themes in the journal were pleas for Bengali-medium education for the children of Bengali government employees who lived in north India, instead of education in the local vernacular which was the norm.Footnote 53 Next in frequency of occurrence were discussions on Bengali literature, language, and culture, including the growth of Bengali literature outside Bengal. Therefore, in its initial years of existence, the journal gave prominent voice to the affective condition of this migrant community as well as their material concerns.

For a journal that opened with a cosmopolitan statement of purpose conveyed in the words of Tagore, the situation had changed with the onset of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal in 1905–06, and its subsequent spread to the rest of the country. Presumably, Chatterjee’s own political and intellectual position had also evolved between 1901 and 1906. As a result, by 1906, the national or jātiẏo perspective became the prime lens for the journal.Footnote 54 While Prabāsī maintained its strident anti-colonial stance, a comparison of the themes of articles published in 1901, the first year of publication, with those published in 1906, shows the dwindling focus on the local. The initial aim of giving voice to the migrant community in the region took a backseat. Instead, there was growing support for a nationalist position. For instance, during 1906–1907, a majority of the articles explored themes such as ‘The Foundation of National Education’ (Jātiyo Shikkhār Bhitti), ‘The Responsibility of Educated People in the National Effort’ (Swodesh Prochestāy Shikkhito Loker Kortobya), ‘National Art’ (Swodeshī Chitra), (Janasādhāroṇer Shikkhā o Jātiyo Sompod o Unnoti), and ‘Nationalism’ (Swodeshī). The authors were largely upper-caste Bengalis; the names of women writers (Hemlata Debi, Priyalata Debi, Sister Nivedita) appeared more frequently than Muslims and there are no identifiable lower-caste contributors. The topics were largely defined by the interests of the elites and middle classes; concerns of non-literate working classes came up only in the context of reform. Essays frequently praised the glories and achievements of Hindu Vedic civilization (‘Baidik Sobhyatā’) and discussed Hindu myths (‘Prāchīn Purāṇa’) at length. An interesting example of the journal’s ideological inclination is available in a critical editorial note written by Chatterjee on a Bengali literary convention in Dhaka organized by Muslims in 1905. He clarified that ‘nationalism is not Hindutva’, and that ‘communalism in literature is not a positive development … the doors of literature are open to all’.Footnote 55 Yet he viewed any attempt by Muslims to reshape Bengali literature with suspicion and labelled it as ‘communal’ instead of a legitimate claim made by a community whose articulations had not been allowed to be a part of the traditional Bengali literary canon.Footnote 56 In the same vein, in articles reporting the activities of the Nagari Pracharini Sabha and those discussing the intimacies between Hindi and Bengali literature (Bongosāhityer Sohit Hindīr Ghanisṭhṭā), the journal made consistent efforts to reconcile the claims of Hindi as a national language for its all-Bengali readership.

These tendencies indicate that the leading vernacular languages of the region, Hindi and Bengali, were being channelled by the leading journals of these languages, Saraswatī and Prabāsī, towards a constricted cultural ideal to varying degrees. Both journals enjoyed substantial readerships in the city and the region and became the main mediums of expression and opinion-building in this period. English, which was emerging as a pan-Indian language, and was associated with a forward-looking, cosmopolitan identity, was hardly untouched by this majoritarian vision.

The Modern Review

Following Prabāsī’s success, Ramananda Chatterjee established the monthly Modern Review to address a nation-wide audience and furnish a space for the expression of anti-colonial sentiments that were growing in Allahabad in the wake of the Swadeshi movement. The Modern Review, like Prabāsī, was also printed by the Indian Press but had a pan-Indian rather than regional audience. Just like Saraswatī in the Hindi public sphere and Prabāsī for Bengalis, The Modern Review went on to become one of the most important and most widely read English-language journals. In the process, it further cemented the reputation of the Indian Press.

Each issue of The Modern Review contained an average of 75–80 pages. In its first year, it offered readers a total of around 115 prose pieces including open letters, opinion pieces, book reviews, editorial notes, and some serialized folk stories and works of fiction. In addition, readers were exposed to a visual feast with approximately 90 illustrations comprising a mix of photographs and reproductions of artworks. The editorial was titled ‘Notes’ and carried several short comments on contemporary socio-political affairs. Given that English was not the language of any specific regional group in India, the target readership of The Modern Review was clearly a pan-Indian English-literate audience who were not tied down to a particular region or its interests. In addressing a diverse audience united only by English and a shared interest in current affairs, The Modern Review pitched itself as the voice of the ‘modern’, suggesting a nexus between knowledge of English, varied political interests, and modernity.

The many local and national intellectuals who published in The Modern Review reflected Chatterjee’s wide-ranging associations from his Calcutta days as well as the network that he had developed in Allahabad. The public spheres of both cities had a profound influence on Chatterjee’s political thought even as he influenced them through his opinion-making. For instance, Brahmo Samajists of Bengal such as Akhoy Kumar Mitra and Shibnath Sastri who were also Chatterjee’s mentors, contributed to both Bengali and English journals. In Allahabad, Chintamoni Ghosh was presumably a crucial part of Ramananda Chatterjee’s circle. Both men were Bengali migrants to Allahabad, and it is likely that they had connected via the Indian Press. Chatterjee also maintained a formal association with the Indian National Congress from the time when he was a student in Calcutta: his political connections most likely brought many Congress stalwarts into the fold of The Modern Review. As a result, many prominent Allahabadi intellectuals regularly contributed to the journal. At the national level, Chatterjee’s Modern Review attracted regular contributions from prominent women leaders such as Sister Nivedita and Annie Besant who supported the nationalist cause. It is worth highlighting here that like many others associated with the Congress, such as Malviya, whom I discuss above, Chatterjee also maintained a long association with the Hindu Mahasabha, culminating in becoming president of the organization in 1928. It is also likely that Chatterjee and Malviya were acquainted with and influenced each other through their shared connections and ideologies.

On the issue of languages and cultural identity, both Modern Review and Prabasi occasionally carried articles that drew on the Indo-Persianate culture of north India. One such example is the story of Prince Shamsher Jang published in the column ‘Folk Tales of Hindustan’ and an article titled ‘The Passing of Shah Jehan’, that discussed Abanadrinath Tagore’s painting of the same name.Footnote 57But these were, exceptions rather than the norm, at least in the years they were published in Allahabad. For example, in the June issue, an article titled ‘The Musalman Opposition’ by E. Piriou, took an unambiguously Islamophobic position in statements such as, ‘The Musalmans of today are the degenerate and despoiled children of the Pathans and the Mughals …’; another sentence claimed that ‘the true Musalman is a fanatic’. This article furthermore, blamed Muslims for falling for the British colonial policy of divide and rule and preventing the consolidation of a nationalist platform: ‘At any rate, the most dangerous enemies of Indian politics are the Musalmans’. The article also claimed that the ‘Brahmins are the most tolerant people on earth’.Footnote 58 The fact that the journal allowed the publication of such articles without any comment or context reflected the shortfalls and ambiguities of its cultural position.

Chatterjee’s own editorial persona as reflected in his two journals, Prabāsī and The Modern Review, displays his strong anti-colonial leanings but also his marked proclivity for cultural nationalism and majoritarianism which only grew with time. Both journals also supported the cause of Hindi as the national language despite publishing in English and Bengali, respectively. For instance, in an article discussing the Mahomedan Educational Conference in favorable terms, Chatterjee writes, ‘One of the most important proposals considered is that while all Mussalmans should learn Urdu as a language, the medium of instruction should be the Vernacular of the province, which should be properly learned. Not to speak of Mussalmans, we think it would be desirable for all Indians to learn Hindustani as a possible indigenous lingua franca all over India.’Footnote 59 Here, Hindustani implied Hindi in the Nagari script, since the reference to Urdu in the same sentence shows that Urdu, which was actually Hindustani in the Perso-Arabic script, had already been deemed a separate language that was largely associated with ‘Mussalmans’.Footnote 60 The clause ‘while’ in this sentence is similarly crucial in distinguishing between Urdu and the ‘Vernacular of the province’, reinforcing the claim that Hindi rather than Urdu was the tongue of the people.

In another similar instance, Chatterjee wrote an editorial essay titled, ‘The Decrease of Hindus’. Drawing the attention of his Hindu readers to the Census Reports, he alerts them about an alleged decline in their population in contrast with the rise of population of Muslims and Christians.Footnote 61 Chatterjee’s comparative and competitive claims based on seemingly objective population figures in fact masks his (and his Hindu readers) unfounded anxiety that Hindus would be outnumbered by other communities and that India would lose its Hindu cultural and social identity. The article ends on this note, ‘Whatever is calculated to conserve the vitality of the Hindu race and save it from decay and ultimate extinction is Hindu: let him dispute it who can or will’.Footnote 62 Chatterjee was not alone in giving voice to such fears and popularizing them through his journal; indeed, many other intellectuals of the period deliberately or inadvertently revealed such biases and prejudices. These perspectives ultimately reflect that The Modern Review assumed that it was addressing a Hindu readership. Contrary to Chatterjee’s and his journals’ contemporary reputations as the vanguard of liberal thought in modern India, these instances show that there was a failure to create a truly ‘modern’ journal which could be an egalitarian platform for all.

Chatterjee’s association with Allahabad ended in 1907. According to biographies, Chatterjee’s anti-colonial rhetoric led to threat of censorship by the provincial government. As a result, Chatterjee left Allahabad at the end of 1907 and moved back to Calcutta.Footnote 63 This implied that Prabāsī and The Modern Review also departed from the public sphere of Allahabad. Chatterjee continued to edit both journals until his death in 1943. Both journals continued to exert immense influence but now their sphere of influence shifted to Bengal.Footnote 64

Adīb

Never in the history of the world was there such a time when languages and learning were made the target of humiliation. Rather, in religion and among worthy people, it has always been considered a standard of civilization (meʻyār-e tamaddun) to acquire more than one language. Associating any special kind of prejudice with any language is detrimental to the progress of civilization (taraqqī-e-tamaddun). In fact, it is the worst kind of moral crime [akhlāqī jurm]. The need of the hour is that not only should the two factions learn each other’s language, but that they should also participate in mutual progress of these languages. In this manner, they should lighten the load of their ethical duty [akhlāqī farā’iẓ].Footnote 65

In contrast with the tone of the other journals discussed so far, Shaakir, editor of the Urdu journal, Adīb, in his op-ed for the Febraury 1911 issue lamented the fact that in the tense terrain of the twentieth century, languages and literary cultures had become the unfortunate battlegrounds of identity politics. But he also sounded a note of optimism and reminded readers that historically, the opposite had been the case; that acquiring ‘more than one language’, in other words, bilingualism and multilingualism had always been the hallmark of civilizational ethos and a cosmopolitan identity. In the face of conservative perspectives emerging from Saraswatī edited by Dwivedi and the two crucial journals edited by Chatterjee, and the growth of majoritarian nationalism in the intellectual networks of Allahabad in the early years of the twentieth century even within platforms that were ostensibly liberal and secular, Adīb’s editorial stance marks a distinct note of dissent. However, unlike the other journals of the Indian Press stable, Adīb has garnered almost no attention within English-language scholarship.Footnote 66 In exploring Adīb at some length, my discussion offers a corrective to both gaps and sheds light on the seminal significance of this journal as a crucial vehicle of cosmopolitan and secular opinion-formation.

Adīb’s first issue was published in January 1910. Each issue contained 50 pages, adding up to a yearly total of 600 pages. The journal enjoyed a robust circulation of 1,500 in 1912.Footnote 67 Its name translates as ‘the learned/the civilized’ and as the content reflects, it sought to attract and cultivate an erudite audience. A short article titled ‘Rules of Adīb’ (Adīb ke Qavāʿid) states that the journal targeted an educated readership which explicitly included female readers.

This illustrated monthly journal is the foremost example of the progress of Urdu learning and literature … Its articles are particularly suited for men and women. No article on religious debates (maẕhabī mubāḥas̱a) or on the current state of politics (maujūdah politics) will be printed.Footnote 68

Before turning to comment on politics and religions, it is important to mention here that none of the other Indian Press journals explicitly mention a female readership. Thus, the reference to female readers was quite exceptional during a period when general-interest journals mostly presumed and addressed a male audience even if women were a de facto part of the audience.Footnote 69 There seem to have been, however, no women contributors, unlike the other journals. By the early twentieth century, across languages and regions, male authors vigorously debated the ‘women’s question’ through the prism of reform. In keeping with this trend, male authors of Adīb also discussed topics such as women’s education and the history of female rulers of India. For example, an article titled ‘The matter of women’s education in Hindustan’ (Hindustān meiṉ Zanāna Tʿalīm kā Masʾla) discussed the contemporary state of education for women.Footnote 70 Similarly, in alignment with the artwork featured in the other journals of the Indian Press stable, Adīb too featured portraits of Hindu goddesses as well as female characters from Hindu epics like Sita and Draupadi. In addition, female figures from the Christian tradition such as the Virgin Mary were also portrayed. The rich potential for an analysis of the gender politics and ideology signalled in such choices would require a separate discussion.Footnote 71

Adīb’s disclaimer about eschewing commentary on religious and political issues must be interrogated further, since it was not borne out by the evidence provided by the contents of the journals. In a place like Allahabad which was the capital of the province from 1858 until 1921 and which emerged as the centre of politics of this region, print culture and politics were distinct yet interconnected domains. The politics of print culture did not merely mirror the political culture of the city but was rather a space for objective analysis and corrective pedagogy. As far as the stance of distance from politics was concerned, the reason might be found in the history of the Indian Press. It is worth noting that Ghosh invested in Adīb in late 1909 after Ramananda Chatterjee’s Prabāsī and Modern Review were hounded out of the city due to the censorship they faced from the administration of the North-Western Provinces.

Moreover, as I discuss in the earlier sections, Urdu was under severe attack by the strident Hindi establishment in the city. In this, the Hindi camp was supported by the Hindu reformist groups who were bent on identifying Urdu and the Perso-Arabic script exclusively with a Muslim religious identity. Ghosh was well-acquainted with the Hindi literary establishment and shared a professional association with them through his press. Consequently, it is possible that Ghosh wished to steer clear of these political quagmires even as he showed faith in the cause of Urdu by sponsoring and establishing Adīb. Even so, as the brief lifespan of the journal indicates, Adīb could not survive the many impediments it faced from the tense scenario in which it found itself.

In its lifetime of less than five years, however, Adīb marked an important intervention in the public discourse and cultural politics of the period. During its years of publication, the journal had three different editors at the helm who were, interestingly, from three different religions: Naubat Rai Nazar Laknavi, a Hindu (January 1910–May 1911); Pyaare Lal Shaakir Merathi, a Christian (June 1911–December 1912); and Hasan Azimabadi, a Muslim (January 1913–December 1913). The case of Adīb presents what I call a curious ‘Amar, Akbar, Anthony’ scenario within modern north Indian print culture.Footnote 72 As their second names show, they hailed from various parts of the North-Western Provinces and it is their association with the world of words that brought them to Allahabad.Footnote 73 The list of authors is similarly diverse and suggests that readers were not aligned with any particular language or religion but were identified in the columns of the journal by their educational, regional, and professional affiliations, or through their pen names or taḵẖalluṣ. Among the Hindu authors, Kayasthas and Kashmiri Pandits—the upper-caste Hindu communities that traditionally used Urdu—were prominent. This diversity within the production team of Adīb is worth bearing in mind as it speaks to the diverse user base of the language and presented a variance from the case of modern Hindi.

On the issue of frequent turnovers in the position of the editor, Abid Reza Bidaar in his introduction to a collection of articles from Adīb indicates that there were differences in opinion between the proprietor of the press and the editors.Footnote 74 It seems likely that the publisher or one of the editors themselves wished to avoid being considered the mouthpiece of partisan political opinion or even avoid censorship. Furthermore, Adīb definitely steered clear of expressing an explicit anti-colonial stance, which is different from the case of The Modern Review. The fate of Ramananda Chatterjee and his journals may have influenced Adīb’s course in this matter. Perhaps because of this negative experience, Ghosh was both the proprietor and publisher of Adīb, an arrangement that was different from the one he had shared with Chatterjee. As a result, management and, to some degree, even editorial decisions, seemed to have rested with the Indian Press which was distinct from the power-sharing arrangements between the Indian Press and the other three journals I discuss here.

An analysis of the contents of the journal shows that apart from articles which engaged with literary and philosophical issues, most issues contained two to four important articles which held forth on the socio-cultural and linguistic debates of the day. As the above discussion has shown, these were deeply politicized and political matters such as the role of Urdu and its potential as a language, the Hindi-Urdu controversy, Hindu-Muslim relations, the nature of the Indian past, and trends in historiography. An analysis of some of these articles reflects that in discussions on the language question, growth of sectarian sentiments, and the emergent issue of national identity, Adīb’s civilizational ethos and humanistic vision approximated that expressed by Tagore in his poem, ‘Prabāsī’, a clarion call celebrating being at home in the world. For instance, in the article titled ‘Hindu-Muslim differences are superficial’ (Hindū-Muslim Tafrīq Sat̤aḥī Hai), the writer Munshi Tirath Ram Firozepuri emphasizes that differences between Hindus and Muslims are visible to all precisely because they catch public attention so easily. In Firozepuri’s estimation, the surface-level tensions implied that in reality, the differences were superficial. He claimed that on a sustained engagement, the observer would notice that beyond differences, there exists ‘a thread of Hindustani colour that binds everyone’.Footnote 75

Adīb did occasionally intervene on behalf of Urdu in the linguistic debate of the era. For instance, one of the articles in a series titled ‘Urdu as the national language of India’ (Urdū: Hindustān kī Qaumī Zabān ki Haisīyat Se) written by Syed Mohammad Farooq Shahpuri, reproduced a large, translated excerpt of an article by Nishikanta Chattopadhyay, a professor of linguistics in Europe and a native of Bengal. Chattopadhyay wrote that Urdu or Hindustani could claim the status of lingua franca since it enjoyed a pan-India presence that no other language had and was not a regional language.Footnote 76 While Adīb (via this article among many others), took a stance on the language issue, nevertheless it consistently promoted a non-divisive vision of Hindustani. For example, Shahpuri’s article mentioned that the version of Urdu/Hindustani he promoted would draw its vocabulary and heritage from Braj Bhasha and other indigenous literary registers of India rather than rely too heavily on Persian and Arabic. It ends by quoting Iqbal’s poem, ‘Sārey jahāṉ se acchā, Hindustān hamārā’, as an exemplar of the version of Urdu/Hindustani that it envisaged as the national language.

Urdu was indeed unique in its identity as a cosmopolitan Indian language not fully moored in regional or ethnic affiliations. Jennifer Dubrow uses the term ‘Urdu cosmopolis’ to describe this formation. She writes: ‘Urdu readers and writers imagined themselves as citizens of an Urdu-speaking, transregional, yet nonnational community that was global in outlook and consciously resisted national borders or religious identities’.Footnote 77 In the case of Adīb too, Urdu continued to be used by a diverse group of people and remained a language of literary and intellectual discourse even during a time of increasing division.

Despite Adīb’s declaration of intent and avowal of separation between the ʿilmī (scholarly) and adabī (literary, civilized) domain on the one hand, and the siyāsī (political) arena on the other, in articles like this one, the journal took a clear stance on religion and contemporary politics. Such a strategy can be understood by viewing it as a double move of disavowal of anti-colonial politics while embracing a critique of socio-cultural issues beyond the domain of nationalism. Commenting on the trans-national reach of the Urdu public sphere, Dubrow writes that Urdu periodicals played an important role in democratizing access to literary discourse and widened the base of its participants to include writers from different backgrounds.Footnote 78 In fact, the point could be extended further. As the discussion here reflects, journals such as Adīb extended Urdu’s cosmopolitan base beyond a literary readership and into the domain of socio-political discourse by publishing discussions on a wide variety of topics such as contemporary events and current social and political thought.

Thus, Adīb’s contribution was not exhausted by the frameworks of regional or national identity which have been the dominant frameworks of analysis of several textual and journalistic writings of this period. This distance from the national framework also indicates that while the exchange of political and print energies was a significant aspect of the city’s place-making, at the same time print culture and publishers such as the Indian Press seem to have maintained some degree of autonomy. The continued endurance of Urdu among a wide readership in north India for many more years despite socio-political pressures to conform was a significant moment of cultural and social resilience. It is a noteworthy fact that this pushback came not just from the Muslim literati who were increasingly identified as the main adherents of the Urdu language but also from journals such as Adīb in Allahabad and Zamāna in Kanpur: both were produced by a diverse team helmed by editors of various religions. Thus, Adīb remains an important archive and record of Allahabad’s Urdu literary culture and socio-political discourse. Moreover, the fact that Urdu (and not any other language) was used in defence of the ethos of multilingualism as a civilizational value and moral imperative, as reflected in Shaakir’s editorial with which this article opens, marks an important intervention in this seminal cultural debate. As Hindi, aided by the campaign for Nagari, gained dominance and popularity, the important role played by Urdu began to be forgotten or ignored, and today is threatened with active erasure.

In conclusion

By tracing the history of the print culture in Allahabad, and by profiling the Indian Press and its four journals against the background of cultural trends at the turn of the century, this article uncovers the contestations animating the public sphere of the city of Allahabad. The Indian Press’s multilingual book list reflects that its owner, Chintamoni Ghosh, was more invested in ensuring commercial success and sealing the intellectual reputation of his business than in taking sides in the divisive linguistic politics of the day. As a result, due to the efforts of the Indian Press and other multilingual publishers, books in many languages and scripts were published in the region. Meanwhile, in the world of journals and public discourse, the leading journals—Saraswatī, Modern Review, and Prabāsī—catering to Hindi, English, and Bengali reading publics, respectively, adopted a conservative position on linguistic and cultural identity, marking the incursion of cultural nationalist trends within seemingly liberal and progressive platforms. Even though the Urdu-language Adīb advocated Urdu as the lingua franca, it did so on the grounds of defending syncretic values and offered significant resistance to the homogenizing trends. Thus, Hindi, Bengali, English, and Urdu journals managed the task of giving voice to the linguistically diverse population of Allahabad and added to its multilingual culture yet, in the final count, the differences in opinion among them mirror the socio-political contestations in this period.

In such a scenario, the normative potential of multilingualism as a long-standing cosmopolitan cultural ideal in South Asia underwent decline. Instead of the diverse opinions and liberal attitudes that a multilingual milieu supposedly represents, except in one notable instance, we find a broad convergence among the high-brow journals of Allahabad and consolidation of a conservative position. This article has demonstrated that the presence of linguistic diversity does not imply an a priori presence of liberal and cosmopolitan values across the board. Consequently, and somewhat ironically, the multilingual method adopted by this article—comparing print culture in four different languages—uncovers the limitations and decline of the value of multilingualism in this era.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Rochona Majumdar, Ulrike Stark, Dipesh Chakrabarty, and Muzaffar Alam for their insightful comments at various stages of the evolution of this article. Andrew Halladay, Akshara Ravishankar, Ayelet Kotler, Eduardo Acosta, Itamar Ramot, Supurna Dasgupta, Surabhi Pudasaini, and Talia Ariav were the best first and final readers of this paper. A special thanks to Talia for thinking through the stakes of multilingualism in pre-colonial and modern India with me. Niyati Sharma, Devika Shankar, Alastair McClure, and Aparna Vaidik read drafts and consistently encouraged me to publish. I am grateful to panel and audience members at conferences at the University of Chicago, ACSA at Madison, and ECSAS at Vienna for their feedback, especially to the European Association of South Asian Studies for recognizing this paper with an award that proved to be very encouraging. Finally, thanks to the three anonymous peer reviewers for their thoughtful engagement and suggestions.