In 2007, the Social Security Administration (SSA) alerted the national media that the “nation's first Baby Boomer” (Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, “born on January 1, 1946, at 12:00:01”) would soon be applying for Social Security retirement benefits. SSA intended the press release to advertise online applications for benefits.Footnote 1 But ABC’s website gave the story an unwelcome slant. It wrote: “Trouble is, 80 million others are right behind her. Casey-Kirschling is the raindrop that's about to become a tidal wave.”Footnote 2 That wave would—the story suggested—soon crash upon and maybe drown the nation's social insurance programs.

But before Casey-Kirschling could become a harbinger of welfare-state woes, she had to become a baby boomer. And well before anyone could become a baby boomer, a newly influential breed of expert had to invent the baby boom, binding it to a narrative of crisis. And even before that, such experts had to foresee the advent of a “mature” American nation, one characterized by slowed population growth and the possibility of longer, better lives through social planning—a vision for the future threatened by the welling “wave” (or even more often, the “bulge”) of babies.

The “baby boomer” label is now ubiquitous. Indeed, in the inaugural issue of this journal, an eminent historian began an essay by identifying himself as a “first-year baby boomer.”Footnote 3 It is tempting to take this label for granted, to accept it as natural, and perhaps as not that important. The story, however, of a generation falling under the thrall of the baby boomer brand has a history—a consequential one. It is to a surprising degree a history of an influential social scientific concept—the demographic “bulge”—whose career depended on the appeal of approaching politics through technocratic “population” management.

Exploring the history of the baby boomer concept sheds new light on the history of population research in the twentieth century and its place in American cultural and political conversations. As Emily R. Merchant has explained, the interdisciplinary science of demography won cachet and institutional support because of its capacity to pose and solve “population problems.”Footnote 4 In the early twentieth century, for example, the discipline gained attention by addressing fears of white race suicide and racial degeneration and legitimizing immigration restriction and eugenics as possible solutions.Footnote 5 The shock of the Great Depression then embroiled population research in the new project of inventing an “economy” amenable to prediction and state management.Footnote 6 In the thick of the Cold War, researchers described a population “bomb” that could be defused only by aggressive (eugenic, racist) population control programs in the United States and around the world.Footnote 7 Since 1984, demography's focus has shifted to address high mortality in the Global South, international migration, problems faced by aging societies, and the role of population in climate change.Footnote 8 But this literature's attention to the international population bomb has obscured simultaneous concern about the domestic bulge, which threatened to upset the rational, planned welfare state that population researchers were working so diligently to support.

This article examines this history with two intertwined trajectories. First, it traces the development of the “bulge” as a concept over time. That story begins with population researchers struggling to explain rising birth rates within a framework that understood the United States population to be destined for stability or even stagnation. They constructed the “bulge” as exceptional and anomalous. By the mid-1950s, in the face of a decade of consistently high birth rates, population researchers still refused to ditch their overarching framework, and instead decided that this bulge might be the first of many. In a “mature” population and economy built atop planned families, they reasoned, bulges were to be expected, could be described statistically, and might even be predicted. Journalists first gave the name “baby boom” to rising birth rates in 1941, and in 1980 it was a journalist again who merged population researchers’ concept of a statistical bulge with already existing ideas about generations and the collective experiences of those born after World War II to form what Americans now know as the “baby boom generation.”Footnote 9

Second, the article shows how the bulge came to be understood as a cause of crisis. From the very beginning, as population researchers postulated a bulge, they predicted that higher birth rates could cause problems in the age-graded institutions that increasingly guided Americans through their life courses.Footnote 10 Undoubtedly a postwar influx of larger numbers of young people did add stress to many schools. But this development did not originate talk of crisis in elementary education. Instead, school officials and educational commentators introduced the bulge into ongoing debates during the 1940s and 1950s. But in time, the bulge stopped being an ancillary concern and came to be understood as a primary cause of the crisis. Population researchers took this transformation as proof of the bulge's power and went on to prophesy future crises in the nation's universities, labor markets, and welfare programs. In the 1960s and 1970s, sociological and economic theories expanded the scope of possible crises, positing that generation size might be a key factor in explaining broad-based social change or the life chances that individuals enjoyed.

This article cannot adjudicate each crisis claim; it cannot say to what extent demographic factors actually pushed institutions to the brink. Instead, it traces the ways population researchers repeatedly presented the bulge as a looming disaster and prepared the way for a literature setting up the mass of baby boomers as the agents of continuing crisis and disruption in American society at large. I present a history of “baby boomers,” not of baby boomers.Footnote 11 I approach the “bulge,” the “baby boom,” and “baby boomers” as concepts, rather than as people. The fact is that the actual people represented by these concepts have changed substantially over time. Casey-Kirschling was not the first baby boomer. Years before she was born, and even before the United States entered World War II, a rash of births inspired specialists and the mass media to announce a “baby boom.” By the late 1950s, though, researchers and commentators evicted those babies and some 14 million other wartime births from the bulge with their talk of a “postwar baby boom.” The postwar bulge metastasized for two decades, until birth rates fell and one researcher declared in 1966: “the American baby boom is now a part of history.”Footnote 12 Yet, counterintuitively, the number of people in the bulge continued to grow—by as much as 6.3 million people after the baby boom had been declared over—as it embraced immigrants newly allowed into the United States under the Hart-Celler Act of 1965.Footnote 13 The size and nature of the boom still inspires occasional scholarly skirmishes. Some scholars would kick Casey-Kirschling out of the bulge in an effort to make the Census Bureau–approved 1946–1964 boundaries more precise.Footnote 14 Others would argue that the boom might better be broken in two.Footnote 15

The second half of the twentieth century brimmed with people talking about generations. Some concerned themselves with the living masses, while others worked out generational theories by looking to the past.Footnote 16 From amidst that cacophony, an academic concept won naming rights for over 70 million people and defined those millions as a force of nature upending the United States's carefully planned social systems and institutions.

The Anomaly

Population researchers in the years leading up to the Great Depression approached a consensus that the United States had undergone a fundamental demographic shift. In 1928, Pascal K. Whelpton declared to readers of the American Journal of Sociology that the “years of mushroom growth which have been characteristic of the United States in the last century seem to be definitely numbered.”Footnote 17 Whelpton worked at the Scripps Foundation for Population Problems, an institute for population research supported by private funds on the campus of Miami University, a small public university in the town of Oxford, Ohio. Whelpton was a one-time agricultural economist who became the nation's leading population forecaster.Footnote 18 In years to come he would serve as director of the United Nations's Population Division and pioneer new survey methods for understanding American fertility.Footnote 19

Whelpton's forecasts called forth an America that would by 1975 grow at only a small rate or even decline in size. He used a projection method that began with the existing age structure of a population and applied assumed rates of fertility and mortality for the future. Like his peers, Whelpton assumed decreasing fertility.Footnote 20 His methods tracked closely those employed by two life insurance men—Louis Dublin and Alfred Lotka of Metropolitan Life—who took an existing tool for risk making, the “life table,” and adapted it to consider not only mortality rates at each age, but also fertility rates.Footnote 21 Using this tool, Dublin had in 1926 concluded for Atlantic Monthly: “The time of rapid multiplication of our population has been left behind for good.”Footnote 22

Population researchers were far from certain that stagnation would be a good thing, though. Dublin and Lotka first sounded the alarm about an end to growth amid debates over immigration restriction in the early 1920s, a time when many statisticians spoke volubly about the dangers of overpopulation in the United States, lending support to restrictionists.Footnote 23 Dublin attacked the architects of immigration laws and also advocates of birth control for not realizing that their actions would lead to potentially harmful population declines.Footnote 24 Yet he admitted in the face of such declines that “to develop a well-organized and happy society,” whatever its size, should become the goal of “every student of population, every statesman and every thoughtful citizen.”Footnote 25 Whelpton, for his part, spoke hopefully about the future. He decried (with some prescience in 1928, a year before the bubble burst) the “reckless expansion” of 1920s capitalism, and dreamed of possibilities for improving schools, hospitals, and other public services as population grew more slowly. He said: “From now on there should be a better chance to anticipate needs and to plan them wisely.”Footnote 26

Whelpton's population projections and the notion of population “maturity” took firm root in Roosevelt's New Deal welfare state. Social Security old age insurance projections depended on assumptions of slowing population growth and used one of Whelpton's figures to guess the 1975 U.S. population.Footnote 27 In 1938, the Committee on Population Problems of the National Resources Committee spoke of “great changes” and especially a “transition from an era of rapid growth to a period of stationary or decreasing numbers,” alongside lengthening lives, a mobile population, and fears that the poor had too many children and the well-off too few.Footnote 28 To meet the new challenges of that transition, the committee pointed to “an increased emphasis on population research, both in the work of governmental agencies and in the plans of foundations, universities, and various local agencies.”Footnote 29

Whelpton and likeminded scholars of American population maturity were among the first professionals shaping the infant “interdiscipline” of demography. As Emily R. Merchant has explained, population researchers did not coalesce around academic departments, but rather worked in disparate institutional spaces: insurance offices, state bureaucracies, and foundation-funded research centers (like Scripps); here was another example of the sort of structure that Joel Isaac has called the “interstitial academy.”Footnote 30 Demography came bound up in politics, argues Merchant, owing its institutional and financial support as well as its relevance to controversies in the 1920s and 1930s over birth control, immigration restriction, eugenics, and the construction of the welfare state.Footnote 31

By the late 1930s, the interdiscipline had made maturity a key concept. Alan Brinkley and other historians have emphasized how talk of economic “maturity” drove advocacy for state-centered Keynesian economic planning and intervention in the late 1930s.Footnote 32 Population maturity (an intentionally ambiguous concept evoking an aging population and the end of the country's youthful period of growth) was economic maturity's twin. Prosperity and fertility appeared to be declining together. Both justified aggressive state management to escape the current Depression and avoid another.Footnote 33

Yet as population researchers settled on the fact of “maturity,” Henry Luce's Life magazine reported a “baby boom,” bringing that term into wide circulation just one week before the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into World War II.Footnote 34 A three by four matrix of cribs greeted the reader (Figure 1). Tiny (apparently white) babies lay inside—some of whom could be seen wailing, some sleeping, some hiding their faces. What is remarkable about them is not their difference, though, but their sameness. The photographer and editors presented them as a mass of indiscriminate American life, with an accompanying caption asserting that the 2.5 million babies born in 1941 would “look and act like the twelve above.”

Figure 1. Demography as photography: the birth rate depicted in Life, 1941.

The text further figured these babies as a small sample from a larger and more important statistical aggregate. Life ascribed the significance of the “birth rate” to Hitler's bio-geo-politics: “Adolf Hitler has proclaimed that this world war is an inevitable struggle between his fertile German Reich and such sterile old nations as the U.S. and Great Britain.” It continued: “But this year a great baby boom has pushed the U.S. birth rate up to 18.5 babies per thousand of population, while Nazi Germany's is declining from its 1939 high of 20.3. If the trend goes on, next year may see the U.S. winning the baby war against Hitler, in birth rate as well as total production.” Individual babies did not matter in this account. Indeed, the babies pictured mattered only as a stand-in for the larger mass of people rolling off American reproduction lines. When Life gushed that the “U.S. baby boom is bad news for Hitler,” it offered a few possible reasons for the rising birth rate (children from sudden draft marriages or babies that had been put off during the Depression), but paid them little heed, instead seeming pleased to simply bid maturity projections farewell. A week later (the day after Pearl Harbor), Life’s sister publication Time followed up with another “Baby Boom” story.Footnote 35

Rising birth rates, and media attention to them, threatened population researchers’ carefully constructed maturity narrative and rationale for increased planning. They swiftly went to work, explaining the rising birth rate as abnormal, anomalous, temporary, and exceptional.Footnote 36 Embracing the market origins of the “boom” metaphor, they argued that apparent birth rate increases were really cyclical aberrations: babies and business both experienced booms and busts. (Life’s overflowing maternity wards abutted Wichita's “booming aircraft plants.”Footnote 37) William Fielding Ogburn, a leading sociologist and member of the Committee on Population Problems, acknowledged eight years of growing birthrates as of 1943 yet wrote them off as “an upward fluctuation around the downward trend.”Footnote 38 He did not stop there. Ogburn then claimed that the cycles were interrelated, that the baby boom could be explained by the economic boom: “The irregularly rising birth rate in the middle 1930s paralleled the zig-zagging improvement of business during those years.”Footnote 39 Ogburn and his peers read the chart of the birth rate in the same way that 1920s-era market prognosticators and social scientists read price and stock market indices, and they read them alongside one another.Footnote 40

With population cycles, researchers found a way to preserve their faith in inevitable American maturity even in the face of rising birth rates. But in doing so, they began talking about those babies born in the boom as a looming problem. Ogburn postulated that baby shortages late in the war would likely complicate planning for schools and labor markets over the next sixty years. He foresaw a baby “gap,” followed by a “bulge,” each of which would demand very different responses from institutions.Footnote 41 Whelpton contributed to the defense of maturity two years later using an analysis of data from white women, as was typical for such research. He invoked birth “deficits” and “surpluses” (that would cancel one another out) to explain why the growing birth rate did not really mean anything in the long run.Footnote 42 But he also contended that each surplus or bulge meant quite a bit in the short run. Surplus students would pose problems in elementary schools in the early 1950s, and then later in high schools, and then in colleges at the end of the decade and into the 1960s.Footnote 43 Before a single baby boomer (by the current census definition) had been born, Whelpton and his colleagues built a model figuring the baby boom as an exceptional burden throwing otherwise carefully planned public institutions out of balance.

School Crises Become Baby Boom Crises

“Well informed grammar school principals already are thinking of how they are going to take care of a 22 per cent increase in the number of first graders from 1946 to 1949,” asserted Whelpton in a 1945 article for public health officials.Footnote 44 Schools were the primary site where Whelpton and his colleagues anticipated that rising birth rates could bring about a crisis. Since then, one of the most common facts propounded about the baby boomers—especially by population researchers—has been that they brought with them a rash of crowded classrooms and failing schools. However, the children of the baby boom did not so much bring about crisis on their own as displace other explanations for an education system already falling short of expectations. That the bulge became the explanation for a preexisting crisis shows how the concept of the baby boom first made boomers the scapegoats for more complicated social, political, and economic difficulties.

The idea that crisis plagued U.S. schools preceded the arrival of the bulge. Benjamin Fine, a reporter for the New York Times, did much to shape this postwar (but pre-bulge) crisis talk. He toured the nation for a series of articles on the state of the nation's education system, republished in 1947 in a frequently cited book, Our Children Are Cheated.Footnote 45 “The war has hit the schools a disastrous blow from which they are still reeling,” he warned.Footnote 46 Children packed overcrowded, crumbling classrooms, lacking supplies. African American students in segregated schools fared the worst, he said.Footnote 47 The heart of the crisis was a teacher shortage caused by dismal salaries, low morale, poor social standing, and a wartime economic boom that made it more lucrative to be a dogcatcher.Footnote 48

Fine blamed war, not babies.Footnote 49 “Although our schools were not destroyed during the war by enemy bombs,” he wrote, “they were seriously damaged by American indifference. The effects of the war will be felt for generations to come. Millions of children yet unborn will be cheated and deprived of a decent education because of our short-sightedness.”Footnote 50 Schools needed more money, and teachers—whose growing, restive unions Fine reported on extensively—deserved much higher pay and the respect afforded other professions. Population researchers like Whelpton predicted future problems, but Fine and his readers already believed that schools—absent any population bulge—suffered from too few teachers, overcrowding, and underinvestment.

In coming years, the population researchers’ bulge elbowed its way into the conversation about educational crisis. It won purchase first at the local level, where it appealed to bureaucrats who saw both a rational way to govern and a powerful rhetorical tool. One such official, serving on the board of one of the nation's best funded and most influential school districts, was James Marshall of New York City.Footnote 51 A prominent lawyer, rising star in the Jewish community, and a well-connected Republican, Marshall learned about the rising birth rate from public health authorities (maybe even from officials who had heard Whelpton's warnings first hand). As early as 1948, Marshall took to arguing insistently in internal letters that changes to the birth rates demanded and justified asking for more state aid.Footnote 52 He spearheaded a “Special Committee on the Impact of the Increased Birth Rate Upon the Public Schools in the City of New York” to support his case.Footnote 53

Marshall spoke of the bulge as a natural phenomenon that forced the school board's hand. The way that demographic facts appeared immune to argument made them appealing. He touted his “more scientific approach to the study of needs and fixing of priorities” and used it to justify his decisions, much to the chagrin of some fellow officials whose authority he worked to undermine.Footnote 54 When, in one highly publicized instance, a city school superintendent wanted to apply $17 million in state aid to decrease average class sizes from 31.5 to 30.5, Marshall argued that high birth rates made it impossible to pursue such smaller class sizes. State funds needed to be reserved for building new schools by 1952 when “the crest of the wave of new children will have hit our schools.”Footnote 55 The impending bulge (now a crashing wave) justified a decision to back away from commitments to higher standards or greater access.Footnote 56

Blaming the bulge also meant ignoring the past. Marshall's focus on the impending wave distorted the history of underinvestment in congested city schools. Enrollments had in fact peaked in the 1930s at a height the boomers would never reach. Marshall gave primacy to statistical forecasting and so understated the city's past epidemics of overcrowding and a school infrastructure that had groaned under the weight of the willful neglect of city planner Robert Moses.Footnote 57 His attention to aggregate birth rates also obscured the inequities that Fine had critiqued. Marshall's wave swept migrants from the “south and Puerto Rico” into its undifferentiated mass, even as anti-racist activists fought to reveal and redress the particular challenges facing students of color. Beginning in the early 1940s, parent associations like the Schools Council of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Williamsburg requested that space in largely empty, white schools be made available to black and Puerto Rican students attending schools that overflowed with children. Their pleas attributed classroom crowding to the maldistribution of resources, rather than a demographic bulge.Footnote 58

Sometimes obscuring the complexity of a debate was precisely the point of those drawn to population figures. That appears to have been the intention of school leaders in the burgeoning New York suburbs, who counted on vital statistics to win their request for a state-wide bond issue to support school construction in 1950. The state legislature created a special commission because, in the commission's words, “Public concern about the need for new school buildings and the financial ability of localities to construct them had been aroused by the large number of births in postwar years. The average was more than 300,000 a year between 1946 and 1951.”Footnote 59 In this instance, however, birth rates could not distract from the complex conditions that created crowded classrooms. The commission decided against a bond issue and dismissed the claim that birth rates were the cause of the crisis after reporting a long litany of alternative “primary causes of the school building problems,” from suburban expansions to the dispersion of industry out of city centers to Depression-era underinvestment.Footnote 60

Over the course of the 1950s, population researchers’ explanations won more converts in the school crisis conversation—perhaps because birth rates remained high, perhaps because memories of the war faded, or perhaps because the political climate favored arguments built around external, nearly natural causes of crisis. For example, James C. Stone, a teacher training specialist for the California Department of Education, asserted in 1953 that “the basic cause of the teacher shortage is sociological—the result of population changes.”Footnote 61 Although he acknowledged the sort of political and economic factors that Fine had stressed, Stone ultimately concluded that teacher shortages derived primarily from mismatched cohorts: “The high birth rate among people who are parents of school-age children today is in contrast to the low birth rate period of the Depression.”Footnote 62 New teachers recruited from a small generation could not meet the demand to teach the high birth rate group. Where Fine had been supportive of teachers’ unions and their protests, Stone called teachers “their own worst enemies,” arguing that professional complaints were driving away possible recruits. “A plan of action for teacher-recruitment must accent the positive,” wrote Stone.Footnote 63 Population concepts offered Stone a means—in the context of chilling anti-communism—to call for long-term teacher recruitment plans without appearing political.

In 1957 New York City's Board of Education officially blamed the bulge for some of its troubles. It cited “the movement of the wartime ‘bulge in the birth rate’ on to the secondary schools” as the source of high school teacher shortages.Footnote 64 That same year, in a piece arguing for increased public support for universities, the New York Herald Tribune reported: “Everybody talks about the ‘tidal wave’ of students that is going to ‘hit’ the colleges by 1965.”Footnote 65 Such talk could also be turned toward questioning the progressive expansion of access to universities. Carroll Newsom, Executive Vice Chancellor of New York University, argued in 1956 that the coming “deluge” of college students “represents the major contemporary problem with which the colleges and universities must be concerned.”Footnote 66 He invoked a “present emergency”—even though the “deluge” was still a decade away—that justified shunting lower-IQ students into two-year degree programs while limiting access more strictly to four-year colleges.Footnote 67 Grounding his sense of emergency in population research doom-saying, Newsom wrote: “A distinguished scientist is alleged to have said recently that this country, and the entire world, should be more fearful of the present ‘population explosion’ than of the possibility of atomic explosions.”Footnote 68

By the late 1950s, the bulge concept originally proposed by population researchers had won over school bureaucracies, at least to a degree, drawing attention away from the effects of war, educational underfunding, and teachers on strike. Population researchers took their victory as evidence of the dangers of the bulge, even if such dangers were more asserted than proven. So when Ronald Freedman, a population researcher at the University of Michigan, warned of the crisis-inducing bulge imperiling American institutions in 1957—a “postwar baby-boom” that “hit our elementary schools a few years ago”—he drew on and reinforced the new conventional wisdom about the sources of American schools’ troubles.Footnote 69

Mature Economies Beget Bulges

As Americans kept having babies at higher than predicted rates, population researchers faced their own potential crisis. Their projections were failing. “At the present time,” Freedman lamented, “population forecasts are frequently seriously in error.”Footnote 70 Researchers scrambled to understand their errors and to secure the intellectual foundations of their field. In the process, they made the baby boom more real, particularly to those charged with planning and managing the economy. They could not prevent the boom from upsetting existing systems, they claimed, but at least the boom's disruptive potential could be better understood.

For the most part, population researchers in the late 1950s still believed in American maturity, economic and demographic. Derek Hoff terms this faith “stable population Keynesianism,” a belief that economic growth did not require population growth, that the state could steer the economy more productively than the stork.Footnote 71 Population researchers’ work in Cold War development circuits further bound them to the idea of maturity. Their ideology of “demographic transition” assumed a fixed “developmental” path to be trod by all nations—one that led to the long lives, low fertility, and extended economic growth already achieved by the United States and western Europe. At the dawn of the Cold War, American population researchers (most prominently Frank W. Notestein at the Office of Population Research at Princeton University, in a reversal of his thinking during the interwar period) increasingly imagined population control as the starting point for a nation's developmental path to success: declining fertility came first, spurring economic growth.Footnote 72 This interpretation depended on a sort of adoration of national income statistics—which gave reality and definition to “the economy.” In such numbers, population researchers saw the ultimate success or failure of their control measures.Footnote 73 Fat with foundation money and working through new transnational population institutions like the UN Population Division, population researchers trotted the globe consulting with nation-states looking for the on-ramp to prosperity. This entire intellectual edifice depended on the idea that modern economic success marched in lock-step with population decline. The baby boom, accompanied by prosperity, challenged their theories in a spectacularly inconvenient fashion.

In the short term, population researchers turned their apparent quandary into an opportunity. As often happens in predictive enterprises, Whelpton failed to accurately project the American population and was subsequently rewarded for that failure with a succession of generous grants to discover why.Footnote 74 Whelpton teamed with Freedman and Michigan's Survey Research Center on the “Growth in American Families” study, an investigation into the fertility choices of American women. The team sent out female interviewers to talk with 2,713 people who had been selected to be a representative sample of all married, white American women.Footnote 75 Researchers justified their reliance on such a homogenous sample in terms of accuracy (following a long tradition of segregating demographic data), but the choice nonetheless reinforced white, heterosexual norms and the presumption of pathology attached to people of color.Footnote 76 In other studies conducted around this time, researchers noted an earlier decrease in fertility rates among African Americans during the 1920s and 1930s, but the so-called “health hypothesis” blamed epidemic venereal disease instead of crediting widespread family planning. Later studies undermined the health hypothesis and revealed the extent to which population declines, and the subsequent increase in black populations, paralleled those trends among whites.Footnote 77 Segregated data reinforced a false sense of profound population differences shaping the bulge.

Whelpton and Freedman emphasized the need to better understand how economic and social planning should account for population dynamics in an age of planned families in their pitch to the Population Council, a key funder of population work around the world. They wrote: “The American birth rate has fluctuated widely in the last several decades, because most Americans now plan the growth of their families both as to number and spacing.”Footnote 78 As they recruited interview subjects, the researchers claimed in one letter that their work might help those planning their families, especially those experiencing difficulty having children, while another letter emphasized the necessity of understanding “the plans of individual families in order that better plans can be made for schools, community facilities, business, and the national economy.”Footnote 79 In still another letter, they talked about crowded classrooms.Footnote 80 The interviews themselves asked detailed questions about children conceived, miscarried, and born, about contraceptive practices, and about the ideal number of children in a family—all of the sorts of questions that would seem central to family planning. But they also borrowed questions from the Survey Research Center's long-running Consumer Finances Survey, such as: “Looking back five years ago would you say that financially you people are better off or worse off than you were then?”Footnote 81 The study bound production to reproduction.Footnote 82

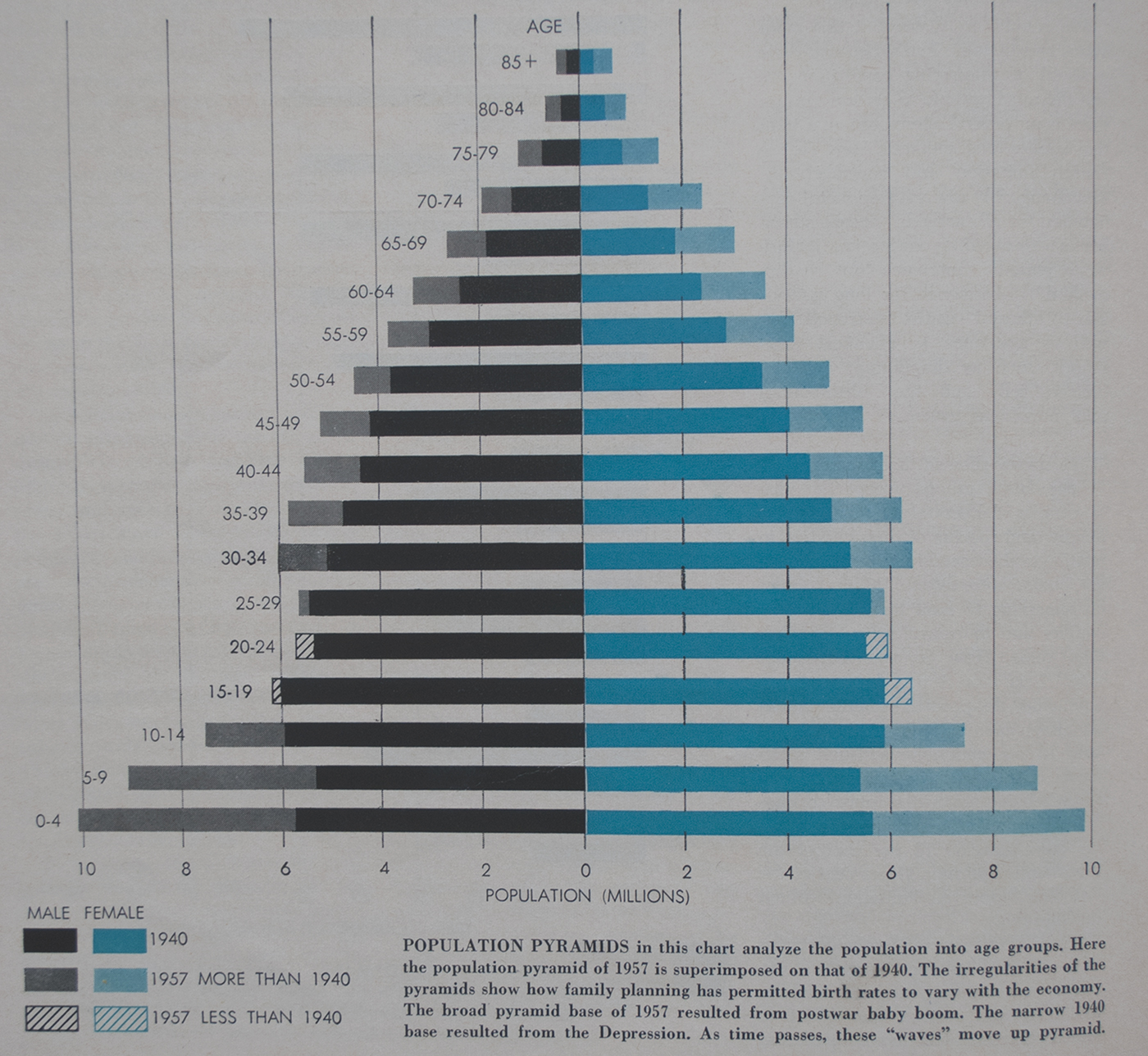

When Whelpton and Freedman published their results, they sought to contain the bulge—and so too the baby boom—within rigorous social science. They demonstrated how best to present the bulge visually with a population “pyramid” (Figure 2). The dark lines, which form an arrow head or bullet, represented the age structure in 1940. Each age group had about the same number of people until the late 1940s, when mortality picked up. The light and slashed lines showed the numbers lost to low birth rates in the Depression and the gains of the baby boom. The last line of the caption read: “As time passes, these ‘waves’ move up pyramid.”Footnote 83

Figure 2. Making the “bulge” visible, 1959. Reproduced by permission of Scientific American.

The study further couched the baby boom within a more general theory of bulges. Whelpton and Freedman concluded that nearly all Americans now wanted only two to four children. Yet the ubiquity of contraceptive practices subjected the economy to anomalous booms and busts. As Freedman explained in 1957: “Even with constant goals for family size, the birth rate may oscillate with swings in the business cycle.” Births, he claimed, could be postponed in bad times, or “borrowed from the future,” when young wives during prosperous times had more of their children earlier than they otherwise might have.Footnote 84 Freedman's language suggested a lay-away plan for reproduction, one that resonated with his assertion that each child had become a “consumption good” that could “yield satisfactions which are consumed rather than investments for the future.”Footnote 85 Bulges presented problems: “A ‘bulge’ of births once created moves up the age-ladder creating a succession of crises as various crucial stages of the life-cycle are reached.”Footnote 86 And such bulges, the study suggested, might be a persistent problem in a mature nation where birth rates echoed business cycles.

Some commentators, however, read the Growth in American Families survey as evidence that population growth was here to stay. In a 1959 Fortune piece, Daniel Seligman and Lawrence Mayer declared that “The pessimism of the 1930s, which foresaw a ‘mature’ U.S. economy enfeebled first by a static population, then a declining population, was in complete rout.”Footnote 87 But they also noted Americans’ ambivalence about the potential of sustained population growth. While writing off the “neo-Malthusians” as alarmists, Seligman and Mayer noted the bind faced by “the sales manager of some Manhattan baby-food firm” whose enthusiasm over a growing market faded when “school taxes on his Long Island home were to be raised for the tenth year in a row.”Footnote 88 Borrowing the discourse of crowding from school debates, they continued: “Americans living in and around large cities are already overcrowded.… If more people imply a greater potential market for housing and automobiles, they may also imply worse slums and traffic jams.”Footnote 89

Most population researchers, though, resisted admitting the end to maturity. While Whelpton and Freedman employed survey data to explain (and excuse) the baby boom, other social scientists turned to historical statistics. Richard Easterlin's early career brought together the measurement of economic growth with questions of fertility in the United States and also the Global South, a set of interests cultivated by two mentors: the econometrician Simon Kuznets and the demographer Dorothy Thomas.Footnote 90 In 1961 Easterlin offered a novel explanation of the baby boom—one that argued that an “unprecedented concurrence” of economic and demographic factors “created an exceptional job market for those in family-building ages and as a result drastically accelerated the founding of families.”Footnote 91 And when the Population Council prepared a set of films in 1964 meant to propound the theory of demographic transition and promote Cold War population control programs, the researcher Ansley Coale admitted that the very high birth rates in the United States reached comparable levels to those of the Latin American “problem” countries that were the focus of the earliest films, but still insisted that the nature of the growth was different and temporary: “the postwar baby boom in the United States was not a return to the family-building habits of before World War I.”Footnote 92

How the Bulge Became a Tyrannical Generation

When Landon Y. Jones's Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation appeared in 1980, the book introduced much larger audiences to ideas that had circulated for decades in the relative obscurity of academic journals. Great Expectations described the demographic research on the baby boom and used that research to explain the generational conflict already preoccupying many Americans. Jones roped the population researchers’ belief that the bulge caused crises to widespread hand-wringing over the generation gap and economic decline. In this way the bulge became a generation with a distinct, untold story: it became “the decisive generation in our history,” one that ruled via a “generational tyranny.”Footnote 93

Jones had landed at the center of the world's population research community in the early 1970s when he took over as editor for the Princeton Alumni Weekly.Footnote 94 It was there that he came to appreciate “the importance of demography and how our lives are shaped by this.”Footnote 95 Princeton hosted the Office of Population Research (OPR), a center for demographic research founded in 1936 under director Frank Notestein, who built OPR from a core of soon-to-be star demographers like Irene Taeuber and Ansley Coale into a premier site for training the evangelists carrying the good news of demographic transition and global population control to the world.Footnote 96 By the time Jones arrived on campus, OPR had taken over the Growth in American Families survey from Whelpton and Freedman, who had gone on to conduct similar studies and implement control strategies in Taiwan. In their place, future OPR director Charles Westoff teamed with sociologist Norman Ryder. Ryder had by that time completed postdoctoral work at OPR and Scripps before joining Wisconsin's sociology department and eventually returning to finish his career at Princeton.Footnote 97

Population research laid the foundation for Jones's project. In his “Notes on Sources,” Jones gave pride of place to a “seminal essay” by Ryder from 1965, one that “for the first time linked the size of a generation to its experience and its social impact.”Footnote 98 Ryder first presented these ideas in 1959 at a meeting of the American Sociological Association, fast on the heels of the first Growth in American Families study. Jones cited Ryder's revised and expanded version, a soon-to-be-classic paper, published in the leading sociological journal in 1965.Footnote 99 Ryder set out to explain why “young adults are prominent in war, revolution, immigration, urbanization, and technological change.”Footnote 100 He dismissed the ideas of many preceding theorists of the “generation,” particularly those like François Mentré who postulated a regular, repeated conflict of generations and whose ideas were popular among some academics.Footnote 101 Ryder insisted that the moment when a “cohort” of individuals reached adulthood, it brought with it the possibility of change. Young people entering a social system without experience or seniority could more readily become the agents of revolution, but Ryder emphasized that “they do not cause change; they permit it.”Footnote 102

Ryder's essay implored his colleagues to bring more demographic methods to sociological research: the survey tradition of sociology specialized in taking cross sections or snapshots that demonstrated stable structures, while the demographers’ cohort method allowed research on change over time and tracked the movement of groups through a system.Footnote 103 Later in his career, as Ryder won awards for his achievements, one of his peers praised him as “the father of a method that no serious demographic textbook can afford to overlook.”Footnote 104 Yet Jones was right to see the way the piece also laid the groundwork for a theory of social change premised on generation size. Social upheaval became more likely in the context of technological change or “intercohort differences,” Ryder argued, singling out for its significance “variation, and particularly abrupt fluctuation, in cohort size.” He had the baby boom in mind: “In the United States today the cohorts entering adulthood are much larger than their predecessors. In consequence, they were raised in crowded housing, crammed together in schools, and are now threatening to be a glut on the labor market.”Footnote 105 Ryder had brought the crisis-inducing bulge to mainstream sociology. Jones would bring it to the nation at large.

Jones appropriated the title for his introduction (“The Pig and the Python”) from a phrase coined by a noted sociologist cum university bureaucrat, the University of California's Neil J. Smelser. In 1975, Smelser had repeated the story of population disaster, of a birth rate anomaly wreaking havoc as it aged: “Crisis and conflict have accompanied the cohort as each institution has attempted to quickly accommodate this large mass of people.”Footnote 106 Smelser introduced a new metaphor for the way the baby boom bulge had troubled schools, colleges, and would eventually “hit” Medicare: “An image I use to characterize this cohort is that of the python which has swallowed a pig.”Footnote 107 The metaphor made clear that the baby boom had come to be defined not only by how much larger it was than the generation it followed, but also how much larger it was than that which followed it.

For Smelser, the most immediate “python” was the University of California system, and he blamed its troubles on the “pig.” He lamented the massive faculty of professors who had been hired and now tenured to educate the bulge of students. He worried that those professors would in time be too curmudgeonly to sympathize with campus protest movements or to effectively teach women and students of color, and that they would hog places in the professoriate. Mostly he worried that they would one day draw many large pensions from the university.Footnote 108

Talk of pigs and pythons avoided politics. That may have been a strategic omission. Smelser knew fraught campus politics first hand. A decade earlier, he had agreed to serve as assistant to the chancellor for student political activities in the immediate aftermath of the Free Speech Movement's demonstrations on the steps of the University of California at Berkeley's Sproul Hall. From his new post, the wunderkind Smelser—already a full professor, editor of the leading sociological journal, and entering university administration at the age of 34—heard the protests of Mario Savio and Michael Lerner, as well as critiques from conservative faculty such as physicist and future Regent John Lawrence. He credited his strategy of “patient listening, neutrality, noncontestation, and distance” with helping allow the Free Speech Movement to collapse in on itself, while giving the university a small reprieve from critics on the right.Footnote 109

But by 1975, the university faced another challenge. Storming into office on a platform that included taming unruly college students, Governor Ronald Reagan oversaw the ouster of university president Clark Kerr, who had joined or led larger national trends toward building federally and state sponsored research programs in order to create what Kerr called a “multiversity.”Footnote 110 Reagan countered with “decidedly conservative budgets,” while a tax-wary state refused bond issues to support the university's continued growth.Footnote 111 The sources of that growth were complex. In the preceding decades, California's population had indeed exploded, owing to immigration and the baby boom, but the percentage of California's college-aged individuals who attended university had also more than doubled between the 1930s and 1960, at which point California's 55 percent surpassed the national average by ten points.Footnote 112 Smelser chose to point to the baby boom as the source of crisis, but Kerr's ambitions and the state's earlier commitment to expanding access were also culpable. The pig in the python analysis allowed Smelser to recast the challenges of the university as technocratic, rather than political. The problem was not student radicalism or California's historical commitment to expanding access to a university education; the problem was one of managing a response to uncontrollable population dynamics, akin to responding to the weather. Jones would go one step further, making the baby boom the primary cause of much of the nation's social change and political unrest.

Population research gave Jones a master generational narrative that could encompass others already in circulation. It could explain the labels applied by earlier commentators at each stage of the baby boom generation's collective lifecycle: “War Babies. Spock Babies. Sputnik Generation. Pepsi Generation. Rock Generation. Now Generation. Love Generation. Vietnam Generation. Protest Generation. Me Generation.”Footnote 113 Pepsi, for instance, created its generation to take advantage of the boom's giant market, Jones argued, not (as historians have since argued) as a response to 1950s-era critiques of corporate culture or in pursuit of new techniques in market segmentation.Footnote 114

The bulge could also explain war and protest. Writing about Vietnam, Jones suggested that the baby boom's size made the war more likely: the United States could have more soldiers and more deferments.Footnote 115 Jones quoted the Students for a Democratic Society's earlier generation talk—“this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit…. Our work is guided by the sense that we may be the last generation in the experiment with living”Footnote 116—but only to call it “relatively mild” compared to the protest of the boomers.Footnote 117 The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the African American freedom struggle won little mention, perhaps because structural racism was harder to blame on birth rates.Footnote 118 But for the most part, Jones demonstrated the indiscriminate voracity of the bulge-crisis narrative as it gobbled up competing generational discourses.Footnote 119

The bulge could even explain the economic disappointments of the 1970s. Jones pointed out recent work by Easterlin and other economists, whose explanations of the baby boom had developed into a fuller theory of the interplay of generation size with the economy.Footnote 120 Testifying before a congressional committee investigating “demographic discontinuities” (like the baby boom), Harvard economist Richard Freeman, for example, explained: “The baby boom group has had a rather poor relative start in their economic life, and it is likely that their poor portion will persist for a good deal of time. This large generation of people will suffer for many years—possibly for their whole working life.”Footnote 121 The same year that Jones's book appeared, Easterlin argued in Birth and Fortune that the baby boom's size drove competition and impaired its opportunities while its relative poverty discouraged it from reproducing.Footnote 122 Similar dynamics, Easterlin wrote, augured a future where big generations alternated with small generations.Footnote 123 Bulges were to be the norm, rather than the anomaly, and those within the bulges would suffer more than others. But the logic of the regular bulge depended on assuming a static economic system maintained by a state committed to full employment and restricted immigration. Easterlin's theory offered a way to believe in Keynesian management (and excuse its failure to tame “stagflation”) even in the face of what historians now consider the economic sea changes of the 1970s that ended postwar prosperity and swept in a financialized economy.Footnote 124

In addition, the specter of a global “population bomb” probably primed Jones's readers to accept the possibility of a transformative bulge. Many in the 1970s feared the growing population figures that undergirded biologist Paul Ehrlich's 1968 Population Bomb—seeing in them a scourge devouring a finite trove of resources.Footnote 125 Cold War concerns that hordes of young people would tip the Third World toward communist revolution or bring on global ecological collapse found new purchase in the 1970s United States. Nixon's Office of Economic Opportunity pushed birth control in the United States in the wake of spectacular claims that overpopulation triggered crime waves and rampant pollution. Yet many others around the world feared the idea of the “population bomb” even more, seeing in that concept an excuse to exercise control over the bodies of women and people of color and to maintain neocolonial Cold War hierarchies. This second fear manifested itself in protests against “genocidal” birth control programs in poor black neighborhoods and the 1974 revolt of Global South nations against United States–led population control programs at a pivotal conference in Bucharest.Footnote 126 Even if confusion reigned among experts, politicians, activists, diplomats, and commentators about whether the world was overpopulated and whether that mattered, the international debates about overpopulation and Cold War population policies awakened many Americans to the political, economic, and environmental significance of demographic shifts. Just the fact of such a widespread demographic controversy lent credibility to the notion that the baby boom really could have upset the nation's apple cart.

Even though American readers may not have accepted all of Jones's arguments, the baby boomer label slowly crept into everyday usage. Marketers did their part as they talked of baby boomers as potential home owners and increasingly important consumers.Footnote 127 The 1987 film Baby Boom featured Diane Keaton's character asking a librarian for material on “baby boomers, new consumerism, baby food manufacturers, also recent issues of Progressive Grocer and American Demographics.”Footnote 128 In 1988, “baby boomer” made it into the dictionary.Footnote 129 And Great Expectations inaugurated an entire genre of books, praising or blaming boomers for the state of the nation.Footnote 130

“Boomsday”

Even after its first media mishap, the Social Security Administration attempted again in 2008 to use Casey-Kirschling's retirement to advertise direct deposit and garner good publicity. The resulting Associated Press story, run on FoxNews.com, instead fretted about the depletion of Social Security reserves.Footnote 131 Critics of the American welfare state now wielded the baby boomer crisis narrative like a weapon.

Deficit hawks and critics of the welfare state trumpeted the convenient crisis caused by the baby boom's aging. They founded AGE—Americans for Generational Equity—in 1984 to advance their point. Minnesota Senator Dave Durenberger, co-chair of the first AGE conference, insisted that without big changes, the country's “demographic destiny” would result in “generational warfare.” Baby boomers, as AGE participants called them, had begun their lives as victims of crowding but would in 2020 (more than thirty years in the future) cause the succeeding generation to become either victims in turn or revolutionaries.Footnote 132

Funded by major corporations like Archer-Daniels-Midland, Enron, and Rubbermaid, and drawing together politicians with actuaries, academics, bankers, and industry consultants, AGE considered a range of problems through a generational lens, from failures of the education system to trade deficits and the growing national debt, while conference participants debated tax increases, spending cuts, and reductions in benefits or even private alternatives to social security.Footnote 133 AGE warned of the nation's transition to an “Aging Society,” in which “the Baby Boomers will become the first generation of senior citizens unable to draw on the support of a much larger number of younger Americans.”Footnote 134 In this new manifestation of maturity ideas, slowing population growth seemed a hindrance to the welfare state instead of a help. But while AGE often invoked the baby boom's impending disruption, its immediate goal was to build broader support for trimming the welfare state by casting Social Security and Medicare programs as a tax paid by baby boomers to support their already well-off elders.Footnote 135

The political gambit succeeded to a degree. A panel created by the Clinton administration recommended in favor of partial “privatization” of Social Security in 1996. One reporter explained: “Fueling the engine of change is a stark demographic fact: Without revision, the Social Security system is headed for big trouble once the huge baby boom generation, now beginning to turn 50, begins to retire.”Footnote 136 A decade later, George W. Bush attempted unsuccessfully to push through Congress exactly such a partial privatization plan built around individual retirement investment accounts.Footnote 137 The call for privatization persists today, still justified by baby boomer retirements, as revealed by a typical Wall Street Journal op-ed from 2017: “With the increase in the number of baby boomers retiring, there is, and will continue to be, a virtual explosion in the number of beneficiaries, putting tremendous pressure on the system …,” wrote former Vanguard Group chief investment officer Gus Sauter in responding “Yes” to the question “should Social Security be privatized?”Footnote 138

By the time Casey-Kirschling and her peers finally did begin to retire, AGE's rhetoric had spread widely, in no small part because “much of the conservative literature on generational equity was published in the popular press rather than in academic journals.”Footnote 139 Satirical writer (and one-time speechwriter for President George H. W. Bush) Christopher Buckley called the day the boom began to retire “boomsday” and painted it in apocalyptic hues. His 2007 novel Boomsday imagined the efforts of an aptly named Cassandra Devine working with an organization bearing some resemblances to AGE to stem the fiscal disaster that baby boomers would cause. Cassandra pushed forward a legislative “modest proposal,” offering tax incentives to boomers who would take their own lives at age 70.Footnote 140 This was not the first novelistic treatment of the boomers-break-Social-Security narrative. In 1991, Douglas Coupland not only inspired the name for the generation to follow the boomers with his novel, Generation X, but in an appendix titled “Numbers,” told a story with statistics of lucky boomers becoming a burden on economically strained young adults, particularly through Social Security taxes.Footnote 141 The warnings that major media outlets appended to the SSA's promotional material about Casey-Kirschling showed the power of the rhetoric in the press too. All seemed to agree: the baby boom bulge threatened the welfare state and all those Americans who followed. The bulge caused crises. It was a story, as we have seen, much older than Casey-Kirschling and her fellow boomers.

Conclusion

The history of the baby boom began with the ambitions of population researchers to contribute to the project of planning for a mature economy and population. The high birth rates of the 1940s surprised the experts, who predicted that the unexpected babies would complicate the nation's plans. Crowded classrooms and teacher shortages—though hardly new—confirmed for researchers and many school officials the truth of these demographic fears. Lest the baby boom imperil the entire project of rational planning and prediction, as well as global efforts at population control, researchers developed sophisticated theories to describe and explain the baby boom. Bulges became predictable, even ordinary, but they also threatened to instigate social or economic changes that could shake the nation. When population researchers’ social science met the generational contests of the 1960s and 1970s, the encounter gave birth—with the help of some savvy journalism—to the baby boom generation and a new way to tell the story of over 70 million Americans. Today, individuals identify (even if grudgingly) as baby boomers (or Xers or millennials), and the bulge of boomers has been recast as the scourge of yet another set of age-graded institutions (Social Security and Medicare). But this time, the loudest voices denouncing the boomers also target the very welfare state and planning apparatus that first made it possible for population researchers to conceive of the bulge.Footnote 142