Introduction

In his postwar short story Der Wegwerfer (1957), Heinrich Böll elaborated upon the clandestine activities of the ‘thrower-away’. Secreted away in the basement of a large insurance company, the working life of his unnamed protagonist was ‘devoted entirely to destruction’: to sorting out and disposing of the vast volumes of incoming advertising circulars that otherwise threatened to derail the effective operations of the organisation (Böll Reference Böll1995, 598). Though evidently a satire upon the excesses of the coming information society (cf. Strasser Reference Strasser1999), Böll's story also provides an apt entrance point to the peculiar position of erasure as an object of study that we address here. Like Böll's thrower-away, the notion of erasure – as the act or process of removing, effacing or obliterating material (OeD 2022) – has tended to remain largely in the shadows: a marginal presence in the considerable body of research that has explored the history of collecting over the past few decades (eg Elsner and Cardinal Reference Elsner and Cardinal1994; Pearce Reference Pearce1995; Crane Reference Crane2000). Yet as in Böll's story, this elision overlooks the significant role that erasure has variously played in our world.

Just as the thrower-away's subterranean practices enabled business as usual in the offices above, erasure proves a material condition for the preoccupation with remembering and forgetting that is so widespread today – not least in the vast array of scholarly studies that have comprised the ‘memory boom’ (Winter Reference Winter and Bell2006). We suggest that what has been argued of absence in archaeology – that its role ‘should be paid as much attention as the presence of things’ (cf Storm and Olsson Reference Storm and Olsson2013; de Vos Reference de Vos2022, 1) – also pertains to erasure as a cultural practice and phenomenon. Indeed, through shaping the material basis of what is available to be remembered or forgotten, erasure provides a precondition for the very possibility of memory and oblivion (Bannon Reference Bannon2005; Chun Reference Chun2008).

In this article, we lay out some of the grounds for a more concentrated effort to study erasure. Despite its relative neglect, there have been various insightful studies that suggest the breadth and diversity of examples of this study object, as well as the range of scholarly fields it might concern: from the history of science (eg Galison Reference Galison2012) and media history (eg Klik Reference Klik2021) to contemporary art (eg Benzon and Sweeney Reference Benzon and Sweeney2015) and archival science (eg Edquist Reference Edquist, Öhrberg, Fischer, Berndtsson and Mattson2021), among others. But while hinting at the potential for further erasure studies, little attempt has been made to think through which conceptual and methodological tools such a project might demand. What is to count as erasure, for instance, and upon what basis? Should we think of erasure as a simple act or, rather, as the inversion of Bruno Latour's notion of inscription as a sign, not isolated but coupled with its ‘social, cultural and physical affordances and processes that give meaning to it within a temporal horizon’ (Latour Reference Latour2013; Day Reference Day2019, 27)?

As a starting point for approaching these questions, we draw upon a recent trend that has brought the flipside of collecting, memory and knowledge-making into focus. Stemming from distinct disciplinary areas yet intersecting in various ways, such initiatives include the turns to consider the dynamics of forgetting (eg Connerton Reference Connerton2009; Assmann Reference Assmann2014; Plate Reference Plate2015; Beiner Reference Beiner2019), the production of ignorance (eg Proctor and Schiebinger Reference Proctor and Schiebinger2008; Burke and Verburgt Reference Burke and Verburgt2021; Burke Reference Burke2023) and how collections come to an end (eg Jardine et al Reference Jardine, Kowal and Bangham2019; Reardon Reference Reardon2019; Skinner and Wienroth Reference Skinner and Wienroth2019). In particular, we make use of Paul Connerton's oft-cited characterisation of seven types of forgetting, taking inspiration from his claim that ‘[f]orgetting is not a unitary phenomenon’, nor is it intrinsically negative or positive but rather something that needs to be disentangled (Connerton Reference Connerton2008, 59). In making this argument, Connerton suggested that erasure is essentially ‘repressive’ in character. Yet just as different types of forgetting can be identified, there are also distinctive variants of erasure that need to be distinguished beyond simply repression. While a distinction is often made in memory studies between that which is remembered by individuals and society – sometimes discussed in terms of ‘memory in the head’ versus ‘memory in the wild’ (Barnier and Hoskins Reference Barnier and Hoskins2018) – we consider erasure to be prior to this: constituting one of the conditions that determine the kinds of substances the work of recollection or disremembering can act upon. Although erasures can conceivably occur in the heads of individuals, eg by neurological damage, we leave such processes to be considered elsewhere. Where scholars in the human sciences responded to Connerton by suggesting some of the ways in which the psychology of autobiographical forgetting operates, it remains an open question how far memory in the head that has been lost is methodologically available for investigation (Singer and Conway Reference Singer and Conway2008; Wessel and Moulds Reference Wessel and Moulds2008; Conway Reference Conway, Eysenck and Groome2020).

Recognising erasure as a diverse phenomenon in need of disentanglement, we use this article to sketch an outline of its principal types and their characteristic logics. Whereas Connerton's typology of forgetting reproduced, at least in part, a broader tendency to regard erasure as a symbolic phenomenon, we shift focus to place greater emphasis upon its materiality, accentuating what Adam Kaasa has described as the ‘matter of erasure’ (Kaasa Reference Kaasa, Schorch, Saxer and Elders2020). We introduce the following five types – (i) repressive erasure, (ii) protective erasure, (iii) operative erasure, (iv) amending erasure and (v) calamitous and neglectful erasure – based upon the methodological dimension of intention: that is, who is engaged in the erasing and to what ends? The question of motive can certainly prove distinctly ambiguous or opaque to establish, but we have nonetheless ordered our categories according to intent, broadly conceived, as a means of differentiating their specific rationalities. We consider first those types for which an obvious actor can be distinguished and where erasure can be identified as the intended consequence – ie to repress by erasing – before turning to treat those with a less clear agent and intent, where erasure has chiefly been a side-effect – ie calamity or neglect.

For each category, we discuss particular instances of how this erasure has been carried out via historical and media-specific methods: though many of our illustrative examples are taken from the GLAM sector – ie galleries-libraries-archives-museums – we also mention the destruction of buildings, urban settings and digital spaces, to gesture towards what we regard as the broader possibilities of erasure as a critical lens. And much as our foregrounding of materiality leads us to focus on erasure's material practices, the analysis according to intention means we are also alert to the ways in which the discursive and the material are entangled in acts of erasure, variously ‘intra-acting’ to speak with Karen Barad's term (Barad Reference Barad2007).

We propose this new typology as a platform for further inquiry and a means of enabling scholars from a range of disciplines to connect their work to the perspective of erasure. It is therefore intended as a conversation starter and an invitation to reflect upon the potential scope and promise of erasure studies, rather than anything more definitive.

Repressive erasure

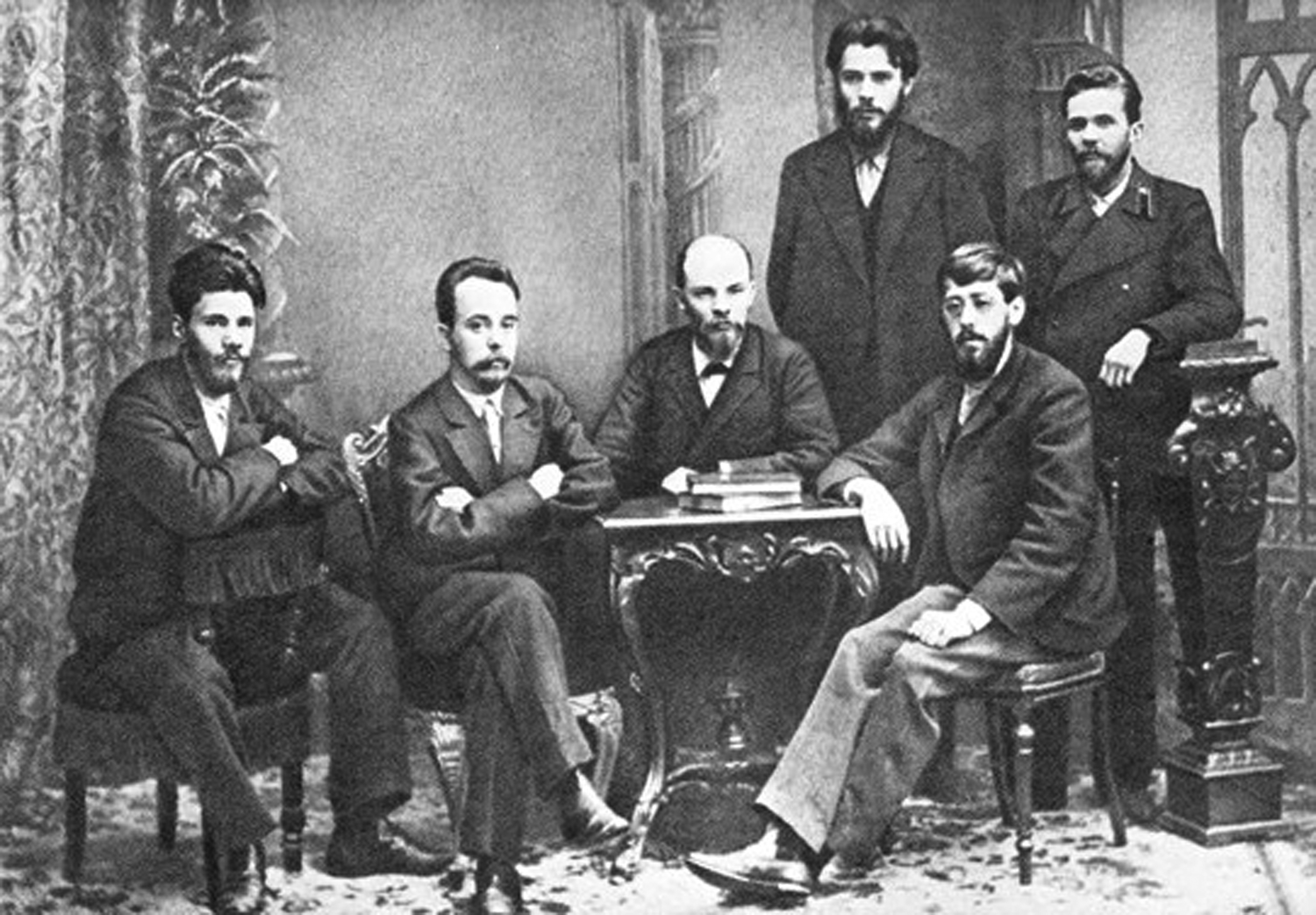

Our first type is borrowed directly from Connerton's schema of forgetting: repressive erasure. This is the version that has been most widely discussed and explored by scholarship in the fields of memory and heritage studies (ie Schindel and Colombo Reference Schindel and Colombo2014; Sela Reference Sela2018). It is also potentially that which is most familiar to broader audiences, given the footage of ISIS's destruction of ancient heritage sites in Palmyra circulating in 2015, or the media coverage of the defacing of the Buddhas of Bayamin at the hands of the Taliban in 2001. The workings of this sort of erasure had previously been captured by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), where Winston's archival operations for ‘the Party’ were centred upon the use of the ‘memory hole’: an elaborate practical system for transporting ‘any document [ … ] due for destruction’ (ie any not consistent with the current Party line) to the ‘enormous furnaces which were hidden somewhere in the recesses of the building’ (Orwell Reference Orwell1967 [1949], 34). While Orwell could not have known all the exact details of the media operations for obliterating the past being deployed at the time – eg the use of cropping, clipping and airbrushing techniques to remove executed political enemies from the photographic record – it is certainly no coincidence that his dystopian vision of erasure drew upon the example of Stalinist Russia. For it was in this regime, in which so many people could be made to vanish, that the systematic destruction of the historical record as a tool of repression was developed into a point of principle (King Reference King1997; Skopin Reference Skopin2022).

Repressive erasure, then, is characteristic of, though far from restricted to, authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. It is a form of erasure that tends to be state-centred and driven, and one that is engineered towards oppression. Imposed upon groups or individuals, it typically depends upon and reproduces a unidirectional model of power: with the powerful enacting erasure upon the identities and heritage of those lacking power, as the vanished or defaced images of discredited Soviet figures during Stalin's purges suggest (Figures 1 and 2). It, therefore, aligns with Zygmunt Bauman's argument about unequal resources in the ‘struggle for historicity’, where ‘[t]omorrow's immortals must first get hold of today's archives’ (Bauman Reference Bauman1992, 57, 170). The impulse towards erasure that this could generate was chillingly encapsulated by the famous slogan of Orwell's novel: ‘[w]ho controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’ (Orwell Reference Orwell1967 [1949], 199). Implicit in which is that to control the past by destruction is to repress through practices of erasure.

Figure 1. Photo of the Union for Struggle of the Liberation of the Working Class (1897) before the Stalinist purges. Photograph by Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869–1939), Wikimedia Commons. Available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Union-de-Lucha.jpg.

Figure 2. The same photo after the Stalinist purges, where the discredited figure of Alexander Malchenko has been airbrushed from the record. Photograph by Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869–1939), Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Petersburg_Union_of_Struggle_for_the_Liberation_of_the_Working_Class_-_Feb_1897_-_Altered.jpg.

An important characteristic that distinguishes our understanding of this term from Connerton's, however, is that we presume it entails specifically and recognisably material processes of destruction. This is significant since there has been a commonplace, if perhaps largely unreflected, tendency to apply the notion of erasure rather in a figurative sense. See, for instance, the headline for a recent opinion piece of a university newspaper: ‘[c]onservative efforts to censor books is a form of erasing minority identities’ (Buchanan Reference Buchanan2021). Yet censoring by restricting access to certain books in school systems exists at a considerable distance from, say, the type of book burning detailed in Ray Bradbury's dystopian Fahrenheit 451 (1953). Connerton uses the term figuratively, too, in discussing the example of canons of art and literature, when he argued that repressive erasure ‘can be encrypted covertly and without apparent violence’. To demonstrate this, he pointed towards the spatial scripting of the Great Hall of the Metropolitan museum in New York, which emphasised the significance of the Western tradition while ensuring that non-Western art is ‘half edited out’. Yet in referring to this occurring through mechanisms such as ‘the implicit injunction to remember’ and forget, it becomes evident that the erasure being characterised here is principal of a symbolic character: the denial of representational space and attention, rather than any physical removal of the historical record (Connerton Reference Connerton2008, 60–61). If such denials are to be regarded as ‘implicit’ instances of repressive erasure, then the field of potential examples becomes disconcertingly wide and diffuse.

To counter this diffusion, we suggest that figurative cases like this are better characterised by other concepts that have been deployed to analyse the marginalising of oppressed groups, such as that of ‘silencing’ (ie Trouillot Reference Trouillot2015; Mason and Sayner Reference Mason and Sayner2019). While the broader perspective of Trouillot and others allows consideration of how historical silences and gaps have been produced by active processes of exclusion – with certain facts prevented from becoming part of the archival record – we argue that there is greater analytical traction in delimiting repressive erasure to those cases where concrete practices of erasing can be identified and, at least to some degree, reconstructed. Symbolic erasure of identities can certainly prove an effect of these practices, but our primary concern is with thinking through the ways in which material practices constitute a precondition for such effects. Repressive erasure, in our sense of the term, thus presumes materiality, as in the case of China's systematic erasure of parts of cities in the interest of writing a history that serves its leadership's current self-perception (Leong Reference Leong and Leong2006).

Protective erasure

In spite of the prominence accorded to this particular form, erasure is not only a matter of oppression. Indeed, the second type we highlight – protective erasure – concerns a remarkably different logic than that of imposed repression. To engage in practices of erasure as protection is to seek to assert a level of control against the imperatives of a wider system for the recording and storage of information. That this has assumed a particular pertinence in the context of digital culture can be illustrated via the character of Lila in Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels. Having taught herself and become an expert on the workings of computer systems, Lila had come to reject what she regarded as the overbearing reach of digital memory. ‘One can't go on anymore, she said, electronics seems so clean and yet it dirties, dirties tremendously, and it obliges you to leave traces of yourself everywhere as if you were shitting and peeing on yourself continuously: I want to leave nothing, my favourite key is the one that deletes’ (Ferrante Reference Ferrante2015, 455). This sense of repulsion, if not violation, at leaving behind her personal data against her will ultimately led Lila to commit to a radical project of ‘[e]liminating herself’ and all her belongings, which proved a very literal embodiment of the European Union's recently legislated ‘right to be forgotten’ (Mantelero Reference Mantelero2013). Faced with the unwelcome prospect of enforced memory, she opted rather ‘to disappear without leaving a trace’ (Ferrante Reference Ferrante2012, 20).

As Lila's carefully deliberated disappearance suggests, protective erasure is something that is proactive and preemptive in character, where the removal of material from the record is desired and actively pursued as opposed to feared. Instead of being about the imposition of power from an external source, it can thus be understood as a means of exerting some degree of control over the shape, and limits, of the recording process and subsequent archive. As an enactment of such archival agency, it can exist across a wide spectrum of levels, from corporate cover-ups and the deletion of files in governmental departments to lone individuals, like Lila, trying to remove their digital footprints (cf Vismann Reference Vismann, Chun and Keenan2006, 102). Insofar as it involves opting out from and resisting the reach of dominant information regimes, as with the example of escaping the data harvesting of the surveillance economy, this is erasure as a tactic with considerable subversive potential (de Certeau Reference de Certeau1984; Zuboff Reference Zuboff2019).

In an interesting twist of historical irony, though, forms of erasure that originated as a means of repression have since been refashioned towards the end of protecting personal integrity. Similar operations to those mentioned above in the case of Soviet-era repressive erasures, where unwanted persons were removed from pictures, are today being employed in the Google Streetview enterprise – yet now for purportedly protective ends. In this instance, the faces of people are algorithmically blurred in the photographic captures of the rooftop-mounted 360-degree cameras; to make its visual documentation of the world's roads compliant with privacy laws, Google renders the visages of those who use these roads unrecognisable (Burbridge Reference Burbridge2020). Our faces are thereby treated like material unfit for public display, such as pornography or depictions of violence or racism. The technical skills required to perform erasures on this massive scale are the flip-side application of the very methods developed to computationally identify human faces and correctly match them to records of individuals, eg at airport security checkpoints (Frome et al Reference Frome, Cheung, Abdulkader, Zennaro, Wu, Bissacco, Hartwig, Neven and Vincent2009).

While it is true that these actions, whether performed by individuals or corporations, have been taken in response to the ‘untamed social frontier’ of digital living, the principles of protective erasure are far from unique to our present moment (Mayer-Schönberger Reference Mayer-Schönberger2009; Fertik and Thompson Reference Fertik and Thompson2010). Nearing the end of his life, Franz Kafka had instructed his friend Max Brod to burn most of his writing. Though these instructions were never sent, Brod found the author's message in his desk after his death and ultimately decided to disregard this wish for destruction. Though the example of Kafka might qualify as a failed attempt at protective erasure, it highlights the sensitivities surrounding writers and their own ideas concerning the fate of their accomplishments (Cohen Reference Cohen2015).

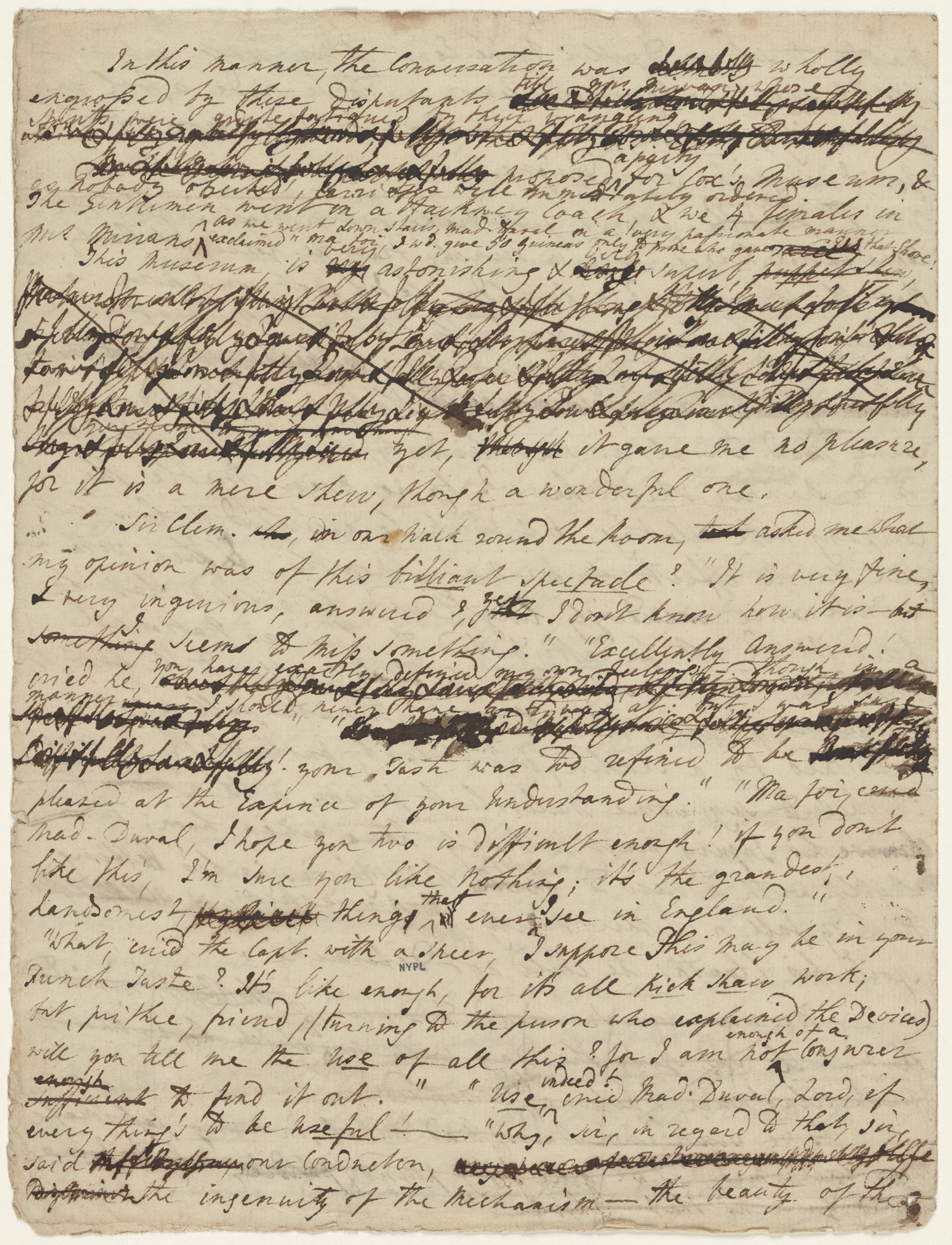

As Kafka's case suggests, the desire to resist unwanted archival attention has a longer history beyond the birth of the internet and can be identified in a range of different cultural settings, prompted by various historically specific informational threats. For instance, the emergence of a market for celebrity biography and published editions of personal correspondence led certain nineteenth-century authors to erase what they deemed as unflattering elements from their prospective archives – with Charles Dickens going so far as to burn all his letters on a huge bonfire (Dickens Reference Dickens2011 [1893], 501). As the scribbled-out sections of Frances Burney's diary indicate, removing those traces that were to be shielded from future publics made this into a project of archival self-fashioning directed at managing posthumous reputation (Figure 3). Another, more haunting example of these practices was when Soviet citizens took to defacing disgraced relatives from private photographs as a means of reducing the danger of repressive crackdowns from the secret police, in the event that the images should later be discovered intact (Skopin Reference Skopin2022). In a sense, this can be understood as an internalising of the official position on the non-existence of such ‘unpeople’, but it also provides a charged instance of erasure as survival in a complex and threatening social environment. Erasing controversial images and texts in their homes was a prudential measure to try and stay safe.

Figure 3. Should it stay or should it go? Frances Burney's partially erased diary page. ‘Madame d'Arblay's diary’, Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1778–1823. Available at https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e3bf1ab0-ab5a-0133-aa3c-00505686d14e.

The intricate dynamics of erasures by authorities, on the one hand, and members of the general public, on the other, are analogous to those of censorship, which can be employed by a range of actors, to various degrees and to different ends, including self-censoring (Bunn Reference Bunn2015). The protests against China's strict Covid policies in the autumn of 2022 can be viewed as a cunning riff on the power of absence. Erasing, as it were, the messages of criticism from their boards, demonstrators appropriated the signature of censorship – blank spaces, ie figuratively erased content – to communicate their disapproval of the regime. In this instance, the idiom of repressive erasure was turned into a vehicle of protecting the rights of expression. The clever simplicity of symbolically erased words made it difficult for the government to classify the nature of the dissent (Rosen Reference Rosen2022). While not a case of protective erasure in the style of Ferrante's protagonist or Soviet households, the protests in China testify to the transgressive force of erasure as protection.

The delicacy of politically motivated erasures are also reflected in attempts to liberate people from misrepresenting bureaucratic procedures. For instance, how do we account for the erasures involved in problematic acts of record keeping? Which erasing measures, in turn, might be required to set the record straight or, in the words of John Michael Rivera, to ‘undocument the documented’ (Rivera Reference Rivera2021, 5; see also Best Reference Best2011; Hinding Reference Hinding, Massman and Kathman1982)? And unmaking things once made, it should be noted, involves considerable effort and always gives rise to new remainders (Weber Reference Weber, Gille and Lepawsky2021). Such questions are related to what has been called the ‘an-archivic’ dimension of the archive – that is, its blindspots towards its own operations, including what is deleted but not recognised as such: it ‘forgets (represses) how it represses’ (Hutchens Reference Hutchens2007, 52). If there is a counter-memory strategy to be found in exposing the inherent erasing aspect of all archives, we suggest that it must be deemed a sort of protective erasure directed not at specific documents, but at the very concept of documentation itself.

Despite the considerable and obvious differences between the contexts of personal data protection today, celebrity privacy in nineteenth-century print culture and the blank spots of Soviet family albums, we argue that a distinctive logic of protection can be discerned that nonetheless links them together. In each case, practices of erasure have been engaged as a means to minimise the risk from what was regarded as potentially dangerous or harmful material, and to project at least some level of control upon the future.

Having distinguished between repressive and protective erasure, we must also note that such a distinction depends largely on the perspective assumed, rather than being ontologically stable: my repression can be your protection and vice versa, as the recent ‘statue wars’ suggest (Gregory Reference Gregory2021; von Tunzelmann Reference von Tunzelmann2021). Moreover, while acts of protective self-erasure might seem to hazard the integrity of the official record, in denying the public a right to know and thereby acquiring repressive qualities, there are also specific circumstances in which a government's ostensible repression of someone's account could be performed as a protective measure in relation to some larger, admirable, end (Cook and Waiser Reference Cook, Waiser, Avery and Holmlund2010). Ultimately, operations of erasure cannot be separated from questions of politics.

Operative erasure

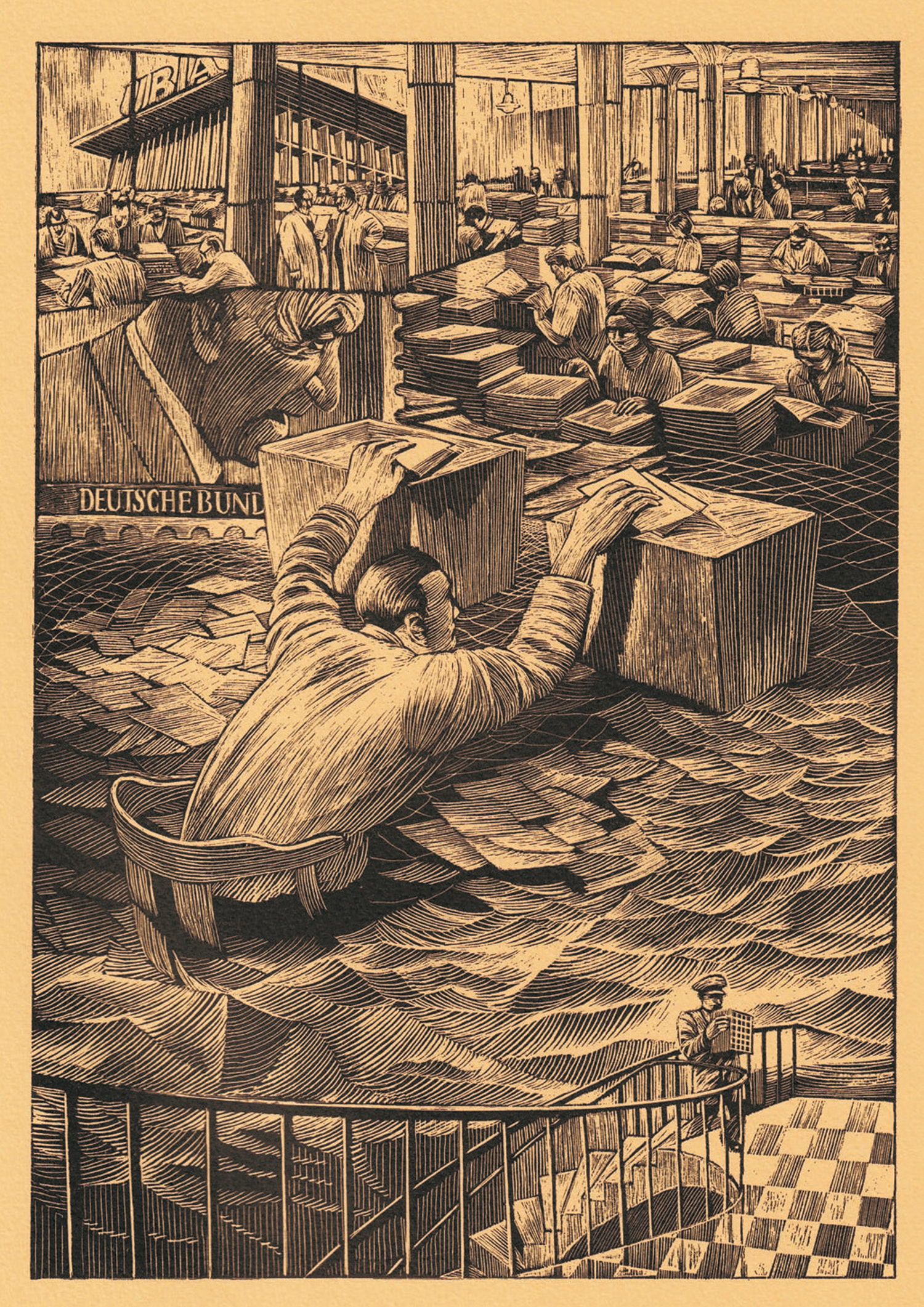

Both repressive and protective erasures suggest a certain drama of agency, centred upon the urgent need or desire to destroy. Yet there are also decidedly less dramatic and more humdrum forms of erasure, as exemplified by our third type: operative erasure – understood in a Weberian sense, of seeking to increase bureaucratic efficiency (Kalberg Reference Kalberg1980). Indeed, perhaps the most widespread instance of erasure today and historically has been as a procedural activity, which is integral to everyday administrative practices such as collections management and data processing. In this form, erasure is neither an accidental occurrence nor an extraordinary measure, but rather adherence to protocol: ‘a feature of the technical system, not a bug’ (Klik Reference Klik2021). It is precisely the routine character of such erasure that means it tends to remain hidden, if not overlooked entirely – as with the emblematic case of Böll's thrower-away (Figure 4). This may be the most common yet least observed form of erasure: by being unspectacular, it disappears from view.

Figure 4. The thrower-away seeks to manage the prospect of paper overload in the office. Illustration to Heinrich Böll's Der Wegwerfer (1957) by Hannes Binder. © Officina Ludi, Grosshansdorf/Germany 1997.

The classic instance of operative erasure is the deaccessioning of archival holdings. In the history of archival theory, the concept of erasure – commonly known by the term ‘appraisal’ – has played a critical role in distinguishing between distinctive cultures of preservation: how erasure is carried out has served to define a broader view on what preservation is for, ie show me your erasure policies and I will tell you what kind of archival tradition you belong to (Tschan Reference Tschan2002). Yet the culling practices this necessitates have been so integrated into the work of archives that they are often understood as an aspect of collections management, and therefore excluded from more principal discussion concerning their actual nature – ie as erasure. In addition, there are the materials excluded from collections in the first place as a result of such appraisal, which are inherently difficult to assess the nature of, still less to judge the consequences of their omission. Given erasure's significance in regulating what is being retained for future reference, we suggest that it is not only intrinsically related to efforts of collecting but also as worthy of scrutiny as the establishment of a collection (Schwartz and Cook Reference Schwartz and Cook2002; Chartier Reference Chartier2007; Vismann Reference Vismann2008). ‘The good archivist,’ as Richard Cox reminds us, ‘is as good a destroyer as a preserver’ (Cox Reference Cox2003, 7). As much as being centres of preservation, archives are also sites of destruction.

The principal justification for the erasure of archival material historically has been neither the repression nor the protection of certain groups of the population discussed in earlier sections, but rather the less remarkable yet forceful certainty known as the economy of storage. The relentless and perennial desire to free up space – from storehouses and shelves to servers – only intensified when storage media became reusable, eg magnetic tapes, hard drives and flash memories. Operating in a reality of finite resources and faced with the continual prospect of overload, archives have had to strike a balance between their explicit mission and available supplies of labour and storage, as well as the material and technical conditions at hand. And because the thinning of existing collections has been potentially controversial – given the tendency to regard older acquisitions as inherently more valuable and earlier enterprises to secure them as prior investments – the act of archival discarding has habitually been positioned as close to the source as possible. Such conduct, while rational from a records management perspective, has contributed to the indistinct figure of erasure practices within institutional settings: who is doing the deleting and where is it taking place, exactly? (Cox Reference Cox2003; Cook Reference Cook2011). On a material level, operatively motivated erasure is carried out in a number of ways. Generally speaking, sending files to the furnace or recycling station before new accessions have been fully integrated into existing collections and submitted to routines has been far simpler, faster and cheaper than later hand-picking to remove specific items.

Among the less obvious kinds of erasures which bear upon the handling of information are compression and encryption. The latter technique was implemented by major data owners in 1970s Sweden to counter the novel right of citizens to request the erasure of their data from government records as granted by the world's first national data act of 1973 (a key event in the prehistory of the EU's later ‘right to be forgotten’). Interestingly, the right to erase given to the population in the name of privacy was immediately seen as a threat to valuable data collections managed by government agencies. To these agencies, encryption – less permanent and damaging than more traditional variants in the arsenal of erasure procedures – was envisioned as a method which enabled a very precise, and reversible, hindrance to data retrieval, effectively approximating an access policy for who could view what. To encrypt instead of eliminating provided the benefit of adhering to the law while leaving the valuable data capital unspoiled. This standard can be understood as an early move in the general direction towards a non-erasure regime, ie an order where key players in the global economy of data exchange will strongly advise against and technically discourage any erasure of data whatsoever. Notably, what amounted to a practical ban on information erasure (at least of the permanently destructive kind), coincided with a strong societal commitment to the reuse and recycling of household and industrial waste products as a reaction towards wasteful ways of living. This move, from destruction to reuse in public waste management, was reflected in the new policies to protect databases by letting data circulate and refraining from erasure at all costs (Fredrikzon Reference Fredrikzon2021).

Another noteworthy form of operative erasure, long since critical in telecommunication networks, is compression. Simplified, according to a defined formula, this shrinks the total sum of information – eg in an image or sound clip – in a manner that will retain an amount sufficient to the specific purpose at hand given other limiting parameters such as available storage or bandwidth. JPEG files, for instance, erase bits from images that the human eye cannot perceive on a normal screen, thus enabling reduced file sizes. Compression as a concept is able to encompass both a technically distinct and usage-specific method to ‘make smaller’, as in Sterne's account of the history of the MP3 format, and also be extended into a cultural technique fundamental not only to media recording and storage but to the human sensory apparatus and the logic of abstraction (Sterne Reference Sterne2012; Galloway and LaRivière Reference Galloway and LaRivière2017). Whether or not erasure is understood to be the object of a specific type of compression, it nonetheless remains an integral part of the operation; to make a thing more compact, something has to go. While not commonly seen as compression per se, similar erasing effects take place in acts of photocopying and scanning. If, as is often the case, paper supports are discarded when printed materials are digitised, this operation entails the destruction of a specific artefact for the benefit of improved access to content.

Erasure according to the rhythm of operative procedure has even proved a distinctive feature in the long history of knowledge management, not least as a strategy to reduce the extent and redundancy of records to make scholarly work more efficient. Such action, which Ann Blair has discussed as early-modern remedies to problems of information overload, involved the recombination and recategorisation of research items whereby certain data were omitted or brought out of context for the benefit of scientific progress (Blair Reference Blair2010). The resulting fragmentation of former orders of arrangement might be considered a form of erasure pertaining specifically to structure. And certainly, such challenges of excess information are still with us today. Once they grow in number, forms, petitions, applications, memos, etc, tend to be described in organic terms with a catastrophic tenor: mountains of paper, storms of data, sheets springing forth like flooding rivers; a living force that must be tamed. What used to be individual documents are now measured in cubic feet or gigabytes (Vismann Reference Vismann2008). To mitigate the dire outlook of being washed away by records, mechanisms and procedures of erasure have been instrumental.

Operative erasure, then, can be categorised as a typically large-scale, everyday operation that is performed close to collections management, knowledge work and data processing. Blending in with the ongoing and the mundane, it is often poorly recognised as such and neglected as a research subject. If it might be objected that emphasising the routine, impersonal character of such operations risks a silencing of the political – a falling in line with the apparently autonomous workings of the neo-liberal state – we would counter that it rather offers a pertinent means of highlighting and scrutinising the politics of erasure: whose rationality is being enacted via such operations and to what ends (see e.g. Bowker Reference Bowker2005)? By bringing things to the surface that might otherwise go under the radar, this type of erasure is a potent area for further critical investigation.

Amending erasure

Whereas the types of erasure discussed thus far have generally concerned the removal or rubbing-out of ‘completed’ artefacts or collections, our fourth type – amending erasure – typically has a distinctive processual quality. This means a kind of erasure that often works to correct or revise elements of text or data as an inherent part of producing them, for instance in changing the appearance of a word, paragraph or artwork in the course of its development. We argue that this type of erasure is not simply a matter of making-right, nor an act by which a former order may be re-erected, but rather something that is ‘productive’ – in the sense that it not only takes away but also adds something to the world, ultimately influencing relations of power (Foucault Reference Foucault1977; Brothman Reference Brothman1991, 81).

Erasure is often seen in close connection with, yet perceived as opposed to, activities regarded as generative in nature. A typical example is how the disappearance of so-called primitive cultures around the turn of the twentieth century spurred ethnographic interest that influenced the invention of new recording technologies to capture the last utterances of dwindling languages (Hochman Reference Hochman2014). Storage techniques thereby saved forms of life at risk of falling into oblivion. But as Laurent Olivier has stressed, any such undertaking is by necessity also an act of disintegration; in seeking to know the past we have to remove from the artefacts we ‘salvage’ the surroundings of their day that made them coherent and to which they belonged (Olivier Reference Olivier2011). What we end up with may well hide from view that which is truly lost.

A parallel dynamic is at work in more hands-on operations. Paying attention to acts of writing and editing, it is clear that erasures are constitutional to the execution of these elementary performances: in order to write, it seems, we must erase (Giotta Reference Giotta2011, 2). The media theorist Vilém Flusser went as far as insisting that writing is fundamentally about erasure. To write, he suggested, is essentially to carve. What remains from this violent exercise – the negative space where there used to be matter – can be interpreted as a legible pattern and hence be named writing. To make a lasting mark on a surface, excess material first had to be scraped off or chipped away. Writing, in its original conception, can thus be understood as a series of erasures (Roth Reference Roth2012).

Even if we reserve judgement about Flusser's notion of carving, to any experienced writer the work of revision will be a familiar task, commonly recognised as vital to a satisfying result. In fact, as Hannah Sullivan demonstrated in her studies of early twentieth-century modernists, editing – consisting largely of multi-layered erasures – was paramount to achieving the prose which changed literary history (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2013). Investigating the revisions made by Eliot, Pound, Hemingway, Woolf and others, Sullivan relies on the strikethroughs, crossings-out and marginal scribbles left in their manuscripts and drafts.

One feature that helped keep typewriters in the office for decades, even once the computer had begun to predominate, was the successive improvements of the mode of erasure. ‘This Typewriter has a Built-in Eraser’, a 1973 article reported, proceeding to zoom in on the technical novelty: ‘below the right-hand shift key is an additional key marked X. This is the correcting key’ (Wahl Reference Wahl1973, 12). And when the first word processors reached the consumer market, they typically stressed their one major benefit over regular typewriters even to the point where it inspired the product name: The Electric Pencil, ie its writing can be erased. But while the residue of discarded phrasings is readily available to researchers of hundred-year-old documents, the editing made onscreen in the era of word processors (a period dating back to the mid-1960s) is generally harder to locate (Heilmann Reference Heilmann2012). The enormous benefit of seemingly traceless erasures provided by computer-aided composition – attested by authors, clerks and typists used to more hands-on cutting and pasting – also makes it more difficult for literary scholars to uncover erased sentences in archived papers. On this topic, Derrida thought of erasures made before the word processor as ‘scars’ left on paper which provided a ‘thickness in the duration of the erasure’ (Derrida Reference Derrida2005, 24). Knowing what had been removed, he suggested, revealed a deeper layer in the thought process of the writer by presenting a window of sorts to the development of an argument or line of reasoning. In the early 1980s, author Stephen King used his experiences of such traceless – or scarless – deleting as afforded by computer writing in a short story titled ‘The Word Processor’, where the protagonist – also a writer of fiction – can make real-world people disappear by inserting and then deleting their names from the document onscreen (Kirschenbaum Reference Kirschenbaum2016).

A circumstance particularly relevant but not unique to amending erasure is precisely this dynamic of things made to disappear and the traces, however subtle, that such efforts leave behind. For Heidegger, and later Derrida, the crossing-out of a word or expression so that, while appearing rejected, it stayed legible, held a distinct philosophical significance as something there but not quite; unsatisfactory yet necessary (Spivak Reference Spivak and Derrida1976). To this effect, erasures – or better: their traces – could be used strategically to denote the undeniable presence of something partly absent: Kilroy was here. If this technique, known as sous rature (‘under erasure’), signified for Heidegger a lost presence that the stricken-through word was unable to fully convey, for Derrida there was no origin or meaning beyond language; rather absence itself was the condition in need of being identified as our predicament.

Beyond literary, clerical and philosophical editing, the automatic detection and correction of errors is essential in applications where inaccuracies are highly undesirable and performance is a factor. In making the largest camera ever operational (weighing in at 3 tonnes with a sensor of 3.2 gigapixels) to capture ancient events in deep space, a critical part is the automatic removal of interfering satellites in orbit, some 400.000 of them, which risk obstructing the camera's field of view. Without the erasure of these man-made objects, scientists would be distracted by so-called false events (Vera C. Rubin Observatory 2022). Other examples include internet protocols and hard drive storage (Spielman Reference Spielman2009). In these cases, instant erasure of errors interfering with signal throughput and exact readings are algorithmically executed in processes hidden from users. Our confidence in the precision and dependability of many apparatuses and infrastructures ultimately rests on errors being constantly erased at speeds and scales that escape our senses.

Altering the appearance of an existing piece of text or image is not necessarily about rectification. While they employ some of the same instruments as those with obvious correcting goals, erasures made on artistic grounds make the erasing act itself the object of attention. In fact, techniques of erasure in poetry and painting – including whiteouts, blackouts, cuts, painting, sewing or digital deletions – make up an entire class of art practices, with Robert Rauschenberg's erasure of colleague Willem de Kooning's drawing in 1953 often brought forward as a modern beginning (Figure 5). This was a time when ready-mades and everyday objects were actively engaged in the artistic process, their former uses challenged and, sometimes, carefully eliminated. In the context of art, acts of removal raise questions about the destructive–productive dynamic in creative processes (Benzon and Sweeney Reference Benzon and Sweeney2015) and cater to the modernist dream of emptiness, vacuity and nothingness (Dillon Reference Dillon2006). Frequently, erasures have been understood as political critique but also as commentary – ‘dialogical elements’ – on established artistry and historical canons (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2018). Together with artwork based on technical glitches and breakdowns in digital formats and transmissions, erasure art has found several avenues in the online worlds of social media and gaming.

Figure 5. Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), Collection SFMOMA. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Available at: https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.298.

Whether in longhand, on hard drives or in archives, amending erasures are unceasingly being carried out. The veiled character of this widespread erasure work – even when it is motivated by speed or convenience – renders it necessarily political by effectively supporting notions of our collective knowledge repositories, and our interaction with them, as less flawed, more automatic and, consequently, less accessible than is the actual case. This situation is part of a longer history where, for instance, the perception of the photographic camera as an objective and unbiased registrar of a perfect nature in the nineteenth century rested upon extended practices of erasures of imperfect attributes through retouching (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison2007; Giotta Reference Giotta2011). For this reason, to be successful, our methods of discovering what has been removed and why must take into account the specificity of erasure techniques, as well as the sort of traces they leave as they pass through the materials that we want gone.

And as we noted previously, perspective assumes a decisive role in determining which type of operation is at hand: what was true for repressive and protective erasures also holds for operative and amending erasure. For instance, a monument removed from its place could be an act of either repression or protection, yet it might also be an instance of operative erasure where little more was at stake than replacing a piece of public art. Similarly, the reuse of a canvas need not be prompted by artistic ambitions more intricate than those of a limited budget for the procurement of new materials. In such a case, the erasure seems more related to an operative than an amending type. As with any hermeneutical endeavour, context is key.

Calamitous and neglectful erasure

Our fifth and final type – calamitous and neglectful erasure – tangents upon the limits of erasure as a concept. This is related to the problem of agency: to what extent should we accept the term erasure for events of omission occasioned by a non-intentional agent? Do the burnings of books and libraries throughout the millennia belong to a history of erasure, for example? And if so, do we distinguish between arson and accident (Ovenden Reference Ovenden2020)? While the deliberate destruction of books carried out in Nazi Germany may be considered a paradigmatic case of repressive erasure, the unintentional devastation recently caused by fire at the National Museum of Brazil, though perhaps relatable to negligence, cannot be understood in the same way. For such cases, we need a category which seeks no hostile plan yet recognises the ruinous effect. This would be a type that harbours erasures believed to be caused by disaster.

But what about erasures orchestrated by no obvious agency that take place slowly, over long spans of time? With entropy slowly reducing structure in the universe, we might say that physical decay erases information (understood as the statistically unlikely patterns we call order). As Aleida Assmann has suggested with her notion of ‘automatic forgetting’, this sense of continuous erosion can be regarded as ‘the default mode of humans and societies’ (Assmann Reference Assmann2014). On a less astronomical level, however, decay is often the result of forms of neglect. Objects and artefacts that are left without care will disintegrate over time. Their structure will break, their significance fade. And while the actual process of decay may be a matter of chemical decomposition, the steps leading up to this disposition could be attributed to actions, deliberate or not, performed by actors, human or not. Whether to refrain from doing something – to collect, to categorise, to preserve – should be deemed an action is, perhaps, a matter of debate. In any case, it is an observable fact that such avoidance will result in certain qualities or properties of objects to be erased from the world due to the course of decay. Entropy, in this view, is both a natural and a social phenomenon (Lucas Reference Lucas2010).

In recent years, the importance of routines for keeping things in ‘working order’, whether it be archived papers, sewage systems, satellites or grasslands, less they soon fall into disarray and disintegration, has been manifested in fields such as maintenance studies. These vectors of inquiry have brought attention to the fact that technology is no static, one-time installation, nor is it separated or autonomous from the world of humans and the environment. Instead, the machinery we depend on to exist in society is in continuous need of overhaul and repair if only to do what we expect of it (Larkin Reference Larkin2013). In many circumstances, anything short of constant repair will put infrastructure on the road to decay, rendering its services void and its place in the world effectively erased (Henke Reference Henke1999; Denis and Pontille Reference Denis and Pontille2014; Jackson Reference Jackson, Gillespie, Boczkowski and Foot2014; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Erasure through active neglect? An abandoned shopping centre in Malaysia. Photograph by Lee Aik Soon, Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spooky_abandoned_shopping_mall_(Unsplash).jpg.

In digital environments, processes of degeneration differ from those we are otherwise accustomed to. For our concerns, the most obvious effect of the massive dissemination of information which global networks enable is the persistence of the things put there endlessly flowing in ever new constellations (much in congruence with the visions of major data owners half a century ago). Nothing disappears or fades. In more nuanced idiom, this has been characterised as ‘a loss of the confidence of steady decay time’ (Hoskins Reference Hoskins2013). One result of this haphazard traffic is the strain required to rub out things that carry the slightest bit of public interest (much in keeping with current data archiving policy stating that a wide distribution of copies improves the subsistence of a specific piece of information), but to the dismay of those burdened by unflattering or false reputations, calling for a right to be forgotten (which in practice means protective erasure) to compensate for the lack of ‘natural’ waning. As difficult as it may be to permanently remove a piece of information from our vast online depositories, however, the inverse is often true of efforts to preserve digital content for the long-term. Lacking resources and common standards, archives and institutions with related agendas manage to appraise only a fraction of our common digital output. These challenges are compounded by the fact that internet data is subject to decline at speeds and dimensions in orders of magnitude greater than its conventional equivalents. Terms like ‘link rot’ and ‘content drift’ are used to describe situations where 75 percent of the links in the online version of Harvard Law Review no longer work (Figure 7). And more than half of all articles in The New York Times that contain deep links have at least one broken link (Zittrain et al Reference Zittrain, Albert and Lessig2014).

Figure 7. Infrastructural neglect and the aging process of the web. Image, Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:404_error_sample.png.

Whether ‘rot’ is an apt label for this sort of severing of linkage is debatable, especially given that natural processes of decay will not impact digital objects as such. Hardware might deteriorate, become obsolete, and fail in a gradual manner, whereas software and whatever is projected on screen, due to its discrete condition, will either be there – or not. A hard drive infested by fungus might fail, but it will never generate information that bears signs of half-way disintegration in the way a mouldy phone book in print might. There is no wear and tear onscreen like you would see on a restaurant's hand-written menu, say, or in the markings on a board game you have kept from the time when you were young. Things digital age differenty. It is true that they tend to become obsolete quickly and soon require heroic acts to be kept operational in museums. Yet if a digital humanities technician were to boot up a 40-year-old computer, she can continue typing at the command prompt into a document closed on a Friday afternoon 1981, or step into the adventure game she never quite finished, to find them completely devoid of traces from previous visits (Wexelblat Reference Wexelblat and Ishida1998). Related to this is the kind of tracelessness of erasures in digital milieus previously mentioned. Here indicators of historical use – as well as erasures thereof – are not found on worn surfaces, but rather documented in logs or on receipts, much like the way in which we view phone bills or bank statements. For this reason, historians who deal with digital source materials will need to equip themselves with instruments that are able to compensate for the lack of sensory clues normally provided by wear and tear in determining the provenance and biography of the object of study – including what has been erased.

Renouncing the conflation of memory and storage, as well as the equivalence between forgetting and erasure, has enabled the emergence of new perspectives which hold that decay should no longer be rejected or opposed by preservation efforts. In re-evaluating our commitment to perpetual material protection, such initiatives ask whether we can ‘uncouple the work of memory from the burden of material stasis’ to arrive at a care that is not about conservation? (DeSilvey Reference DeSilvey2017, 4). This is an attitude towards acts of collecting and conserving that questions the inherent value of keeping certain orders intact and instead looks to change and vulnerability – not least manifested in processes of decay – as something to support and defend, positing loss as generative and emancipatory (Harrison Reference Harrison2013). It has, one might argue, stronger theoretical bonds to repair and maintenance studies than traditional preservationist outlooks, yet is not content to recognise the material realities of and the ongoing labour required to sustain infrastructure, instead welcoming breakdown and deterioration as occasions rife with potential. Unsurprisingly, these attempts to rethink what is saved and what is discarded draw significant inspiration from ecological thinking (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2012; Holtorf and Ortman Reference Holtorf and Ortman2008).

Practices of erasure have always been at the centre of archives, and processes of decay never quite external to their storehouses. A medium incarnating the paradoxical existence of institutions preoccupied with alternating acts of collecting and annihilating is wastepaper. While an older practice, this term can be located in early twentieth-century records management. It refers to a less durable kind of paper – typically acidic, thin, and cheap – deliberately chosen to support information of too little importance to merit long-term custody (what libraries now collect as ‘ephemera’). Owing to its perishable material qualities, wastepaper is expected to self-destruct by decay irrespective of the active care or passive neglect of curators, and hence requires no attention to accommodate its own passing. Such deterioration by design displaces our ordinary terms of understanding. Extending the notion of the archive as a repository of materials awaiting their disintegration, David Zeitlyn has introduced the term hospice to indicate places that ‘seek to ensure that death is well managed’ (Zeitlyn Reference Zeitlyn2012, 469). Taking things a step further, pace Derrida's Freudian reading of the archive, we might regard it as an entity piloted by an inner death drive – more than to preserve its collections, it wants to be destroyed (Derrida Reference Derrida1996; Savoy Reference Savoy2010).

What we have ecumenically labelled as calamitous and neglectful erasure provides a necessary limit case among the various types of erasure briefly exhibited in this article: a sort of boundary object that demonstrates both the elastic potential and the outer reaches of the perspective we are propounding here. From the embracing of deterioration as politics and potential in heritage studies to the problem of bit rot in online knowledge systems, decay as a willed or inevitable process needs somehow to be accounted for.

Conclusion

In this article, we have outlined and characterised the different types of erasure that we regard as principally important: (i) repressive erasure, (ii) protective erasure, (iii) operative erasure, (iv) amending erasure and (v) calamitous and neglectful erasure. In proposing these distinctions, we are keenly aware of the vital and messy tendencies of erasure – and its complex and multifaceted history – to spill over and subvert the neatly-drawn yet artificial lines of our categories. It is therefore worth underlining that the typology we present is intended neither as binding nor all-encompassing, but rather as an analytical heuristic to think with (or against!) and something that could be tested, supplemented and refined in future work. As a starting point for further studies upon the compelling though elusive object of study that is erasure, we hope it might prove a useful tool for those scholars from a range of disciplinary backgrounds who have touched upon this phenomenon in their research but not necessarily conceived of these connections in such terms.

To conclude, we would like to offer some final reflections on the specific challenges involved in studying that which is no longer present. What kind of object of investigation is erasure, after all? Because few things ever disappear completely in the world, but are rather transformed into new configurations, always leaving behind evidence of their previous existence, erasure studies will typically concentrate on such traces, or on the documented operations or rules of procedures that resulted in their coming into being. We may not be able to examine that which has been deleted, yet by paying attention to the marks and residues where it used to be – with such traces often amounting to a combination of the thing erased and the technique used in its removal – we might amass surprising volumes of new knowledge.

Unlike the footprint or death mask which appear to ‘simply register their world’, a warped indexicality is apparent between what has been erased and the remaining trace, which is recognisable only by investigating the process giving rise to them: the act of erasing (Doane Reference Doane2007, 3). The manner in which something is erased will, logically, affect the quality of the trace produced. The obliteration of a terabyte of data, say, while far from being a purely immaterial act, will nonetheless produce a manifestly different media history than the destruction of a corresponding number of c. 75 million pages of text on paper. In collections management, indices to what is kept may serve this purpose. In the case of a file disappearing, it will still retain its position in the directory, even though the place to which it points will be empty, indicating a lacuna in the record. ‘A lost file’, as Cornelia Vismann noted, ‘can only be discovered if there exists a hint that something is missing’ (Vismann Reference Vismann, Chun and Keenan2006, 103). Such decidedly material gaps where something once was but is no longer might, when discovered, speak quite loudly (O'Toole Reference O'Toole1989; Dauenhauer Reference Dauenhauer1980; Schneider Reference Schneider, Goeing, Grafton and Michel2013).

As a perspective focused upon understanding how and why certain objects have been expunged in history, we suggest that erasure studies are the media archeological approach par excellence. Not in the sense that it seeks to unearth outdated technical gadgetry (Parikka Reference Parikka2012), but in its close examination of the tracks and imprints left by that which is no longer available for scrutiny, as well as the tools and processes employed in order to make it so. Scholars deploying this perspective might thereby find inspiration in Subhankar Banerjee's photography of climate change, which turns to the traces, tracks and vestiges it produces (McKee Reference McKee and Sussman2012; Figure 8). Doing so can help not as a means of searching for ‘the reconstruction of a fragmented unity’ of a true past, as in the visions of nineteenth-century historian Johann Gustav Droysen (Vismann Reference Vismann2001, 205), but rather to understand better the mechanisms shaping the record on which historical inquiry can be based. For if we are interested in coming to terms with the complex and protean world we inhabit, with its perpetually shifting patterns of accumulation, destruction and transience, then thinking about the dynamics of erasure is an excellent place to start.

Figure 8. Capturing the erasures and traces of the climate crisis. Subhankar Banerjee, ‘Caribou Tracks on Wetland, Teshekpuk Lake Wetland’ (2006). Courtesy of the photographer. Available at: https://www.subhankarbanerjee.org/photohtml/arctic-photo-brown-12.html.

Data availability statement

Since this is an analytical position paper, there is no data to be made available.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants of the Heritage Transformation Network, and the research seminar at the Department of History of Science and Ideas, both at Uppsala University, for insightful commentary and feedback. In particular, we thank Martin Jansson and Jenny Beckman for critical suggestions that helped improve our work. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for this journal, since their generous and insightful comments significantly enhanced the final version of the text.

Financial statement

Fredrikzon's work for this research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Haffenden's work formed part of a project grant provided by The Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation (Riksbankens Jubileumsfond) [grant no. P20-0423]. The funder had no role in the design, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

J. F. and C. H. declare none.

Johan Fredrikzon is a researcher at KTH Royal Institute of Technology. His research interests include the cultural techniques of data management, human labour in digital work and the notion of error in the history of artificial intelligence. 2022–2024 Fredrikzon is a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley and Stanford University.

Chris Haffenden is a researcher at Uppsala University, specialising in the cultural and intellectual history of the nineteenth century. His research interests include canonisation, the making and unmaking of cultural heritage, and the history of celebrity culture. He also works with digital research infrastructure at the National Library of Sweden.