Hospital care is an essential part of the health system responsible for looking after one of human beings’ most precious assets: their health. The study of the historical development of hospital systems has become a subject of renewed interest in international academic circles due to its relevance to public health and the dependence on private and public hospital infrastructure for care provision.Footnote 1 Private health insurance (PHI) has increased its weight within this system in recent decades, in a context of cutbacks, waves of privatisations, investment fund interest in this market and a crisis of the welfare state.Footnote 2 As a result of this process, some European countries have a PHI market that supplements public coverage (e.g., Sweden, Spain, Ireland and the United Kingdom). This means that the private sector offers services already provided by the compulsory system, but with extra advantages such as shorter waiting lists and other benefits and comforts. In other countries, PHI plays a more important supplementary role by covering services or specialities excluded from the basic state package (e.g., Denmark, Hungary and the Netherlands). Finally, in some European Union (EU) member states, private insurance provides substitute cover for people excluded from certain aspects of the statutory health insurance scheme for various reasons, such as level of income or type of work (e.g., Germany). Overall, the causes behind PHI are very heterogeneous and a result of historical evolution, the power of different interest groups and the public policies implemented. Its increasing importance, however, is a common trend in all European countries.Footnote 3 Bearing in mind this typology, the population covered by PHI in 2000 varied notably in Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development countries. Among the highest percentages, we find the case of the United States, where PHI covered 71.9% of the population (primary and supplementary), whereas in Europe, the case of the Netherlands stands out with 92% (28% as primary cover, and an additional 64% as supplementary). The lowest percentages correspond to Spain with 13% (2.7% primary and 10.3% duplicate or supplementary) and the United Kingdom with 10% (essentially duplicate or supplementary).Footnote 4

Historically, depending on the time and place, the development of hospitals was based on a variety of charitable institutions, predominant before the nineteenth century. These coexisted, especially from this century onwards, with a constellation of establishments promoted by public and private activity, the market and formulas of solidarity of a civil nature, such as friendly societies.Footnote 5 The coexistence or predominance of one typology or the other depended on both the historical framework and the idiosyncrasies of each country. The first studies available in the international field mainly focused on Northern European countries and the United States.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, in recent decades, new contributions have enlarged the geographical scope of study, which has made it possible to obtain a more heterogeneous and global analysis perspective.Footnote 7

Approaches from disciplines such as the history of medicine, social history and economic history have provided new qualitative and quantitative evidence that has served as a basis for conceptualising the diverse health coverage models and, within these, the different hospital systems in industrial societies. Comparison between countries is very complex due to the variety of institutions, the collaboration or competition between public and private institutions, the diversity of financing and management models that exist, the role of the state in the process, the degree of coverage of the population and so forth.Footnote 8 Thus, in the decades preceding the Second World War, a coexistence of public and private charitable institutions funded by alms and taxes could be found, along with insurance mutuals created by civil associations or firms, PHI companies and limited public health coverage through the first compulsory social insurance schemes. This situation may be described as a mixed economy of welfare for the field of health and hospital care.Footnote 9

During the mid-twentieth century, these diverse paths of hospital development became more integrated and regulated systems. The process was conditioned by various factors such as a country’s wealth, its traditions and its institutions,Footnote 10 its political evolution and the conquest of social and political rights, the weight and financing capacity of the private and public sectors and the dissemination of medical and technological advances and medical professionalisation. By the end of the twentieth century, access to hospital in most EU countries was through different compulsory and universal medical insurance schemes within a broader system of social protection.Footnote 11 However, private medical insurance has gradually gained weight in recent decades, above all since the ideological questioning of welfare states and the application of austerity policies with regard to social spending.Footnote 12 In this respect, the outbreak of the crisis of 2008 had a decisive impact.Footnote 13 As regards the United States, the gradual expansion of health coverage under the Social Security, through the well-known Medicare and Medicaid programmes, targeting the elderly population and low-income groups, respectively, has not overcome the inequalities in access to hospital care and has engendered a great political, business and social debate.Footnote 14 Meanwhile, in countries with planned economy models, the market has been progressively introduced into the health economy since that late twentieth century. This is the case of China, a country where the encouragement of private enterprise after the death of Mao led to a growing commercialisation of hospitals and the erosion of the previous social protection systems, especially for rural populations.Footnote 15

In general, the predominance of the World Bank over development policies in low-income countries, burdened by excessive debt, enabled the imposition of the ‘Washington Consensus’, which spread the idea that single-state welfare models were dysfunctional, while simultaneously recommending hospital provision through a variety of formulas with significant participation of the private sector and widely financed by paying users.Footnote 16 These countries ended the twentieth century with a substantial foreign debt which conditioned everything, including the goal of universal health coverage, which was not even close to being achieved. A recent contribution on the development of the modern hospital examines the growth of this institution in the twentieth century, in different countries, taking into consideration its historical legacy. Focusing on the economic history of the hospital, the study outlines the forms of public and private provision and the political context in which the health systems were created. The collection provides a historical map of the world of different hospital models, including Spain, Brazil, Germany, Central and Eastern Europe, Great Britain, the United StatesFootnote 17 and China. Overall, these comparative cases illuminate the complexities involved in each country and contribute new historical evidence to current debates on the organisation, financing and reform of health care.Footnote 18

The prestigious academic journal Bulletin of the History of Medicine featured an interesting debate in 2020 between leading figures in economic history and the history of medicine.Footnote 19 This collection of essays evidenced the need to combine knowledge from these fields in order to conduct a long-term analysis of such relevant questions as to what extent the logic of capitalism had influenced the functioning of markets, the making of profits and commercialisation throughout the history of medical care. In particular, understanding the capitalist system in its different stages is crucial to analysing the path that the health industry has followed in each country.Footnote 20 From this perspective, we can ask ourselves how the capitalist institutions of medical care, including medical clinics, hospital companies and even insurance companies, have accumulated political influence and market power at different times, and what impact this different predominance has had on health coverage and on the welfare of the population. At the same time, it should be asked whether other legal formulas of health care provision such as friendly societies, cooperatives, trade union funds or lay and Church charitable entities may be considered as competitive capitalist threats for publicly organised medicine or as alternatives to the pursuit of profit in health care.Footnote 21

In fact, the predominance of private actors in the provision of medical care and the behaviour of the prices of this provision reveal its market power and the strength of the state’s role in this area. It seems clear that, in the countries with solid public health systems, financed with social contributions or taxes, and with universal coverage, the private actors have had to seek market niches either to collaborate with public institutions of to cover market failures of the public coverage. It is also very interesting, in this respect, to study to what extent government-run health systems imitate or take advantage of the mechanisms of capitalist markets by, for example, using private organisations to administer public services or introducing competitive conditions in public health care schemes. On the contrary, when public health systems are marginal or are debilitated in terms of coverage and provisions, the market power of the private actors is enhanced and their field of action broadens. At this point, it should be asked to what extent modern health care markets are ‘embedded’ in state power or are a mixture of public and private power.Footnote 22

In any case, there is no doubt that the advance and predominance of profit-seeking actions of hospitals, insurance companies and the pharmaceutical industry have contributed to a profound transformation in the functioning of the economy in general. At the same time, these changes have had consequences for the population’s health coverage and provisions and in terms of inequalities in health care.Footnote 23 There is also no doubt that the economic crises of the 1970s marked a turning point in the management of hospital expenditure at a time when the welfare state and the role of the state in the economy were being called into question. With the argument of managing hospital resources in the most efficient way possible, the private sector assumed an increasingly important role in the main Western European countries. In this respect, it is necessary to extend research beyond the 1970s, when the flow of public and private money into medicine changed to include more powerful external actors such as large hospital corporations or venture capital funds.Footnote 24 From the last decades of the twentieth century, above all, in the more service-oriented post-industrial economies, and in a context of debilitation of public health systems, health care became exponentially profitable, thereby attracting new types of investors ‘without special knowledge in the sector or interest in medicine itself’.Footnote 25 This process has been described as ‘the destabilisation of medical care produced by a new type of monetisation’.Footnote 26 In fact, this new stage entails moving from the commercialisation of health care to its financialisation; that is, medical care becomes just one more financial asset and its price and quality are quoted on the stock exchange.

That said, the question arises as to whether the health care ‘market’ may be considered as a market per se within the capitalist system.Footnote 27 If it is, we should bear in mind the nature of the product. That is, among all the categories of goods and services, medicine and health care are among the most appreciated by the population, as they are crucial not only for people’s survival, but also for their welfare and quality of life.Footnote 28 The recent global pandemic has only reinforced this basic idea. There is still much to be learnt about what causal relationships distinguish the economic history of health care. In dealing with this challenge, it is essential to establish the thread of historical continuity between the incipient capitalist forms, modern capitalism and the trend towards financialisation in recent decades, and how these changes have impacted on the provision of such an inelastic and fundamental good as the care of our health.

This paper aims to contribute to this international academic debate so relevant to the present moment, focusing on the case of Spain. Specifically, this paper aims to analyse the historical development of the private hospital sector in Spain coincident with the start of the democratic period, from 1975 to the present. The study intends to participate in the debate initiated by historians of medicine and economic historians with the aim of tracing capitalist traits and market participation in the evolution of health coverage, a process initially promoted by professional doctors who converted their consulting rooms into small clinics and larger hospital companies and which, over time, saw the incorporation of financial capital.Footnote 29 In particular, this paper has two specific objectives. First, to analyse the relationship of collaboration and/or competition between public and private hospitals under democracy and the factors that have conditioned this relationship. Second, to make an initial contribution towards understanding how, in this context, the large private hospital groups have been created in Spain during this period, especially in recent decades with concentration in the hands of financial capital, originating from both the traditional banking sector and investment funds. The role of the hospital takes on special importance in the Spanish health system, which has been identified as ‘hospital-centric’ by some authors.Footnote 30 The literature available for the case of Spain has highlighted the prominence of the hospital within the health system and has also determined defined stages in the development of public and private hospitals since the passage of the first compulsory sickness insurance in 1942.Footnote 31 However, the historiography has also pointed out the existence of diverse territorial models in this area, especially since the devolution of health care responsibilities to Spain’s so-called Autonomous Communities (regions) after the establishment of the current democratic regime.

Public and private hospitals in Spain since 1975: collaboration or competition?

In the twentieth century, the Spanish hospital system was largely determined by three fundamental laws: Ley del Seguro Obligatorio de Enfermedad [the law introducing compulsory sickness insurance], passed in 1942, Ley de Bases de la Seguridad Social) [the law establishing the Social Security], in 1963, and Ley General de Sanidad [a general health law; hereinafter LGS] in 1986.Footnote 32 The first two contained the dictatorship’s political strategy in the hospital sphere, which lead to delaying the creation of a modern, coordinated hospital system in Spain until the 1970s. The LGS, passed during the democratic stage that was initiated in Spain in 1978, incorporated two key aspects for hospital interests. First, the strictly public management model contemplated a priori in the LGS was soon called into question as the private sector was guaranteed a portfolio of ‘privileged’ clients: civil servants and some other public employees. Thus, the law retained the possibility of an annual choice of insurance for the mutual funds of these public servants, a possibility that constituted an exception within the national health care model.Footnote 33 In 1989, of the six million people covered by private companies, around two million corresponded to public servants who had opted for the private sector instead of social security, whereas the rest had double coverage (public and private).Footnote 34

Second, the LGS incorporated the possibility of ‘establishing agreements for the provision of health care services with means external’ to the public health administrations, which meant the possibility of agreements with private health care and also considered the option of private hospitals linked to the public health service and patients treated in authorised private centres at the expense of the public administration. In fact, these first two aspects were already being applied within the health framework in Spain and the LGS only consolidated them. It should be borne in mind that the mutual funds of public servants had been functioning since the 1970s, and public expenditure on agreements with private health services had not ceased to grow since the start of Spain’s democracy.Footnote 35 In general, from the times of the Franco dictatorship, the decision had been taken to develop an independent health care network for the Spanish health system rather than reaching agreements with existing service providers in the public sphere, such as municipal and provincial hospitals.Footnote 36 However, and in parallel, a policy of special agreements was consolidated, which led the public health sector to a clear financial and consumer dependence on private health care. In this way, the demand for public health care became a key source of profits for private health businesses. This process can be seen clearly in the hospital sphere, and it was consolidated to a certain extent by the LGS of 1986.

Third, the belated passage of the LGS meant that this process overlapped with the devolution of responsibility for health care to the autonomous communities.Footnote 37 Consequently, the law afforded regional governments considerable scope to manoeuvre and only established the general foundations of the health system and guarantees to maintain a certain coordination of the system as a whole. This situation led to the consolidation of different territorial models of health management, characterised by significant inequalities in the public–private hospital tandem, in terms of both management and the provision of services, which had already become evident before 1986.Footnote 38

The years following the passage of the LGS were notable for two processes. First, public health coverage in Spain reached 81% of the population in 1975, 90% in 1985 and 99% in 1990, after the inclusion of the population treated up to then by charitable services.Footnote 39 Second, the LGS initially set up a mixed funding structure for the national health service, with most funds coming from income through social contributions. Nevertheless, the Ley de Presupuestos Generales del Estado [the law regulating the general state budget] passed in 1989 modified this system of financing health care by introducing taxes as the main source of funding. Within this process, the weight of social contributions was gradually reduced in favour of state funding through taxes between 1980 (75.2% and 24.8%) and 1989 (27.25% and 72.8%). A decade later, in 1999, the first budget that included complete funding of the public health system on the basis of taxes was passed.Footnote 40

A key element in this situation was the tax reform promoted by Fernández-Ordóñez in 1977, as this increased the tax-raising capacity of the Treasury. The fiscal reform introduced the taxation principles of the welfare state and established some taxes equivalent to the rest of the EU.Footnote 41 In practice, two key elements can be highlighted. On the one hand, the number of taxpayers increased because personal tax privileges, which some employers and professionals benefitted from, ceased to exist. This was true, above all, for capital income, due to the disappearance of bank secrecy. On the other hand, tax revenue increased to new levels that would have been impossible with the liberal tax system, with the raising of legal tax bases and the obligation to file tax declarations. It was quite another matter, however, whether fraud would actually disappear under democracy and whether in practice the tax system would really be as progressive as in the legislation.Footnote 42

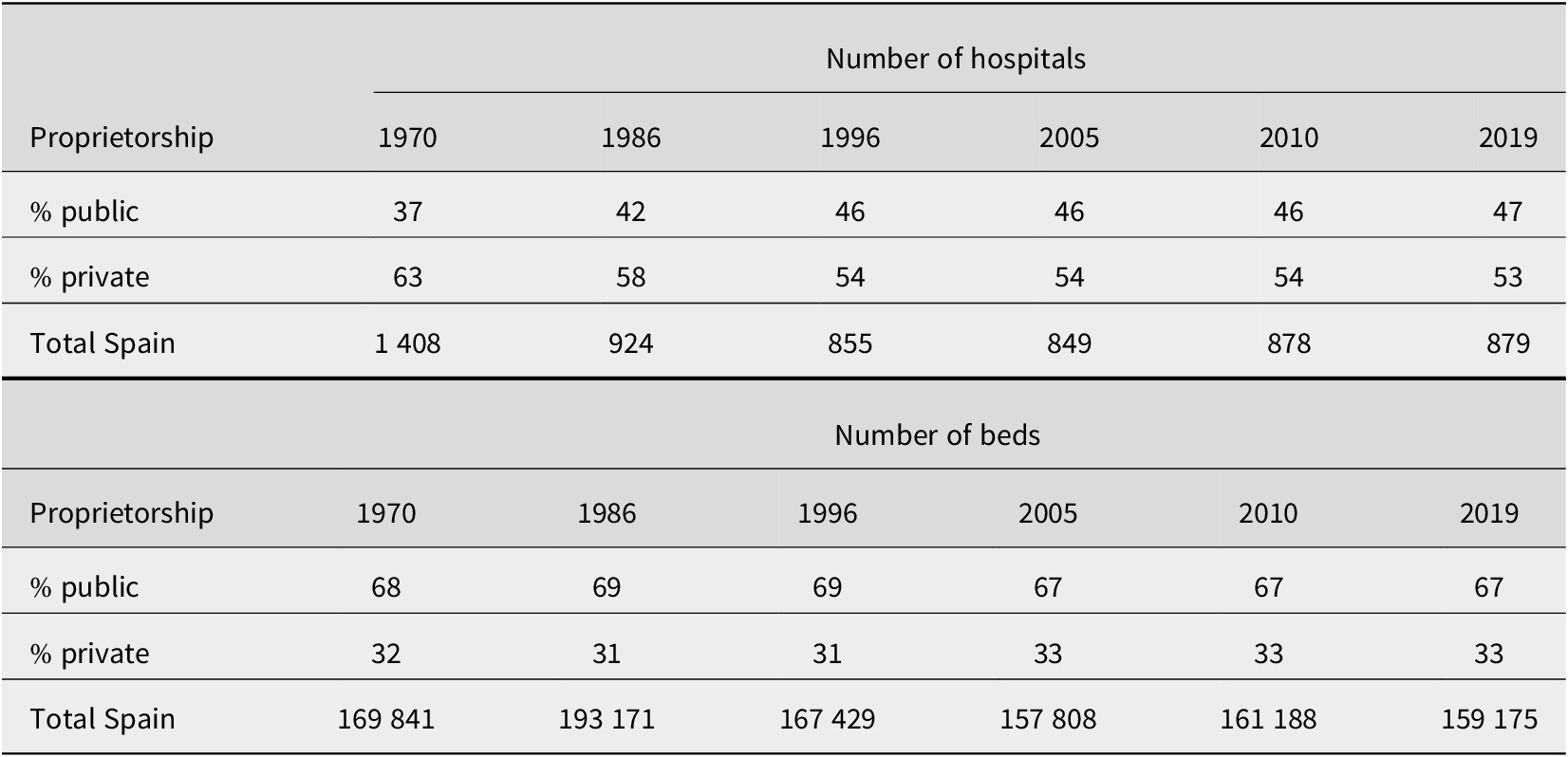

Within this context, the configuration of the public and private hospital system barely experienced changes from 1986, except a slight trend towards a percentage reduction in the number of private hospitals and an increase in their size in terms of beds (Table 1). This was basically due to takeover and merger processes in this area in order to gain investment capacity and modernise facilities during a stage of great technological changes and expansion of the public hospital system.

Table 1. Composition of the public and private hospital system in Spain

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Catálogos Nacionales de Hospitales, 1970, 1986, 1996, 2005, 2010 and 2019.

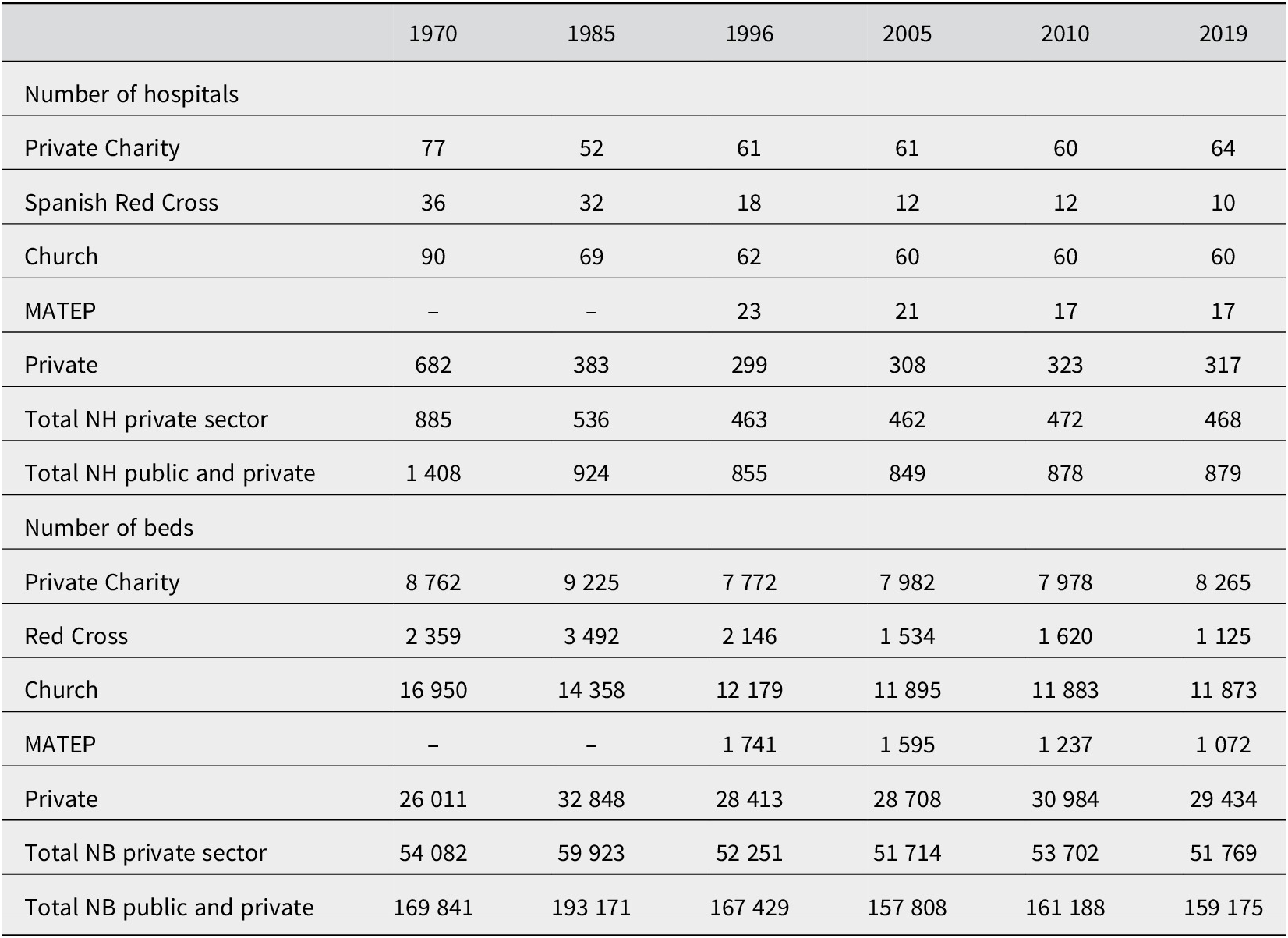

If one analyses the internal composition of the proprietorship of private hospitals from 1970, a fall in the number of hospitals of around 30% for each type can be observed (Table 2). In this section, private charity hospitals show the slightest fall in the number of hospitals. It must be taken into account that this category includes the so-called third sector hospitals, that is, hospitals belonging to the Church and private foundations, which have experienced a notable growth in recent decades. With regard to the number of beds, the evolution is very similar, a fall in all typologies and slighter in private charity hospitals. Moreover, it is important to note that although the number of for-profit private hospitals has fallen (1970: 682 and 2019: 317), the number of beds they provide has increased (1970: 26 011 and 2019: 29 434). This once again reaffirms the increase in the size and capacity of these facilities in recent decades. This clearly indicates that it was the small clinics and hospital companies that gave way over time, either because they closed due to being unable to compete with large companies and private health enterprises, or because they were taken over by these larger concerns.

Table 2. Private hospitals classified by proprietorship

Abbreviations: NB, number of beds; NH, number of hospitals; MATEP, mutuas de accidentes de trabajo y enfermedades profesionales (workplace accident and occupational illness mutuals).

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Catálogos Nacionales de Hospitales, 1986, 1996, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019.

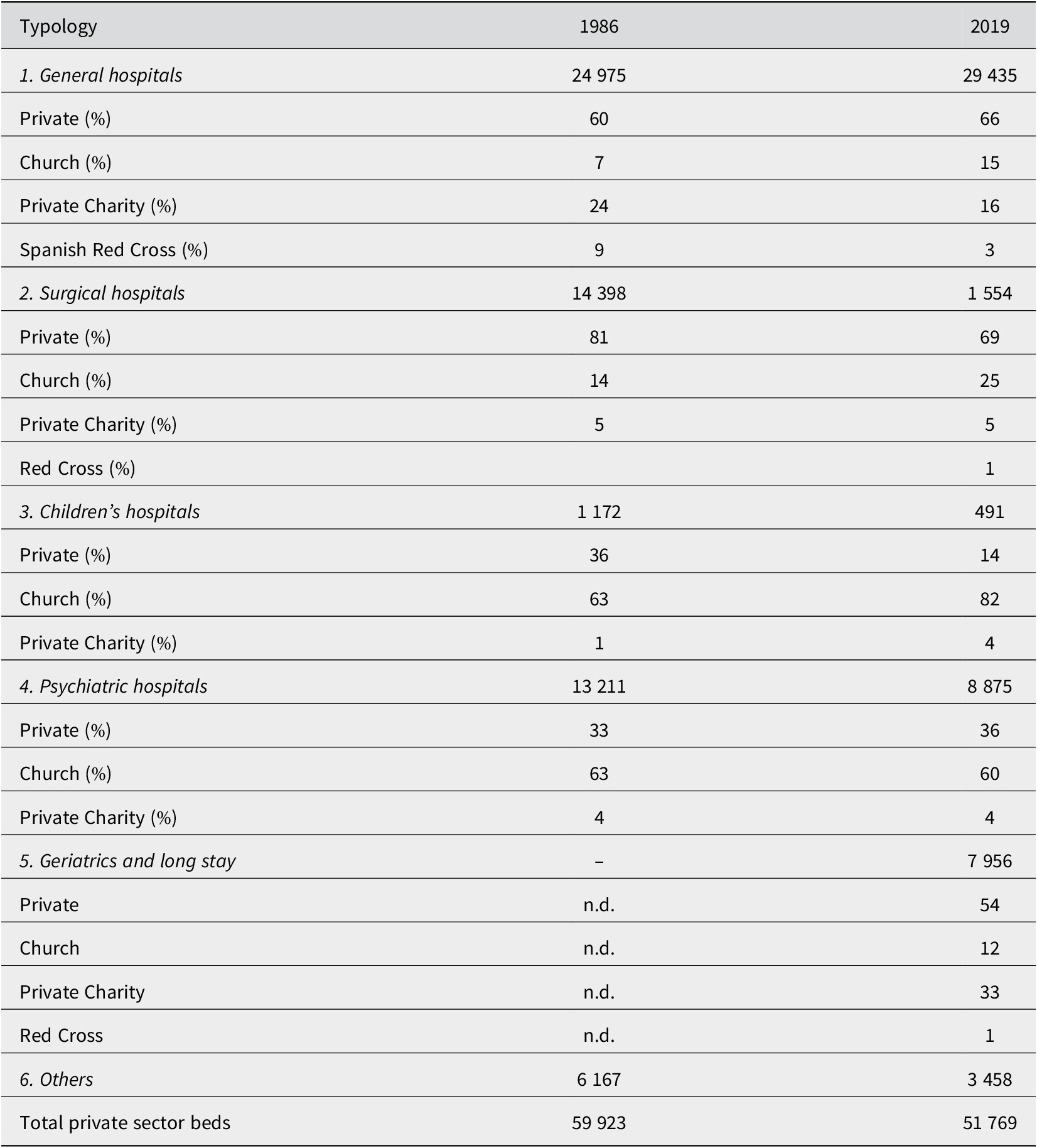

As well as this process, it is also possible to observe a certain progressive specialisation of private hospitals during the period under study (Table 3). Hence, Church-owned hospitals have become predominant among psychiatric and children’s hospitals, whereas the hospitals of private companies have been concentrated above all as general hospitals and also as surgical hospitals. It is noteworthy that private charity hospitals have gradually and progressively lost weight over time, except in the ‘Geriatrics and long stay’ category, which is also an area of growing interest for private companies in a context of progressive ageing of the population and the possibility of signing agreements with public institutions for the subsidised provision of hospital beds. However, as already mentioned above, the so-called third sector hospitals, that is, those belonging to private foundations, are included within the ‘private charity hospitals’ category. This typology and its functioning need to be examined in greater depth in future versions of this study.

Table 3. Composition of private sector hospital beds in Spain by typology

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Catálogos Nacionales de Hospitales, 1986 and 2019.

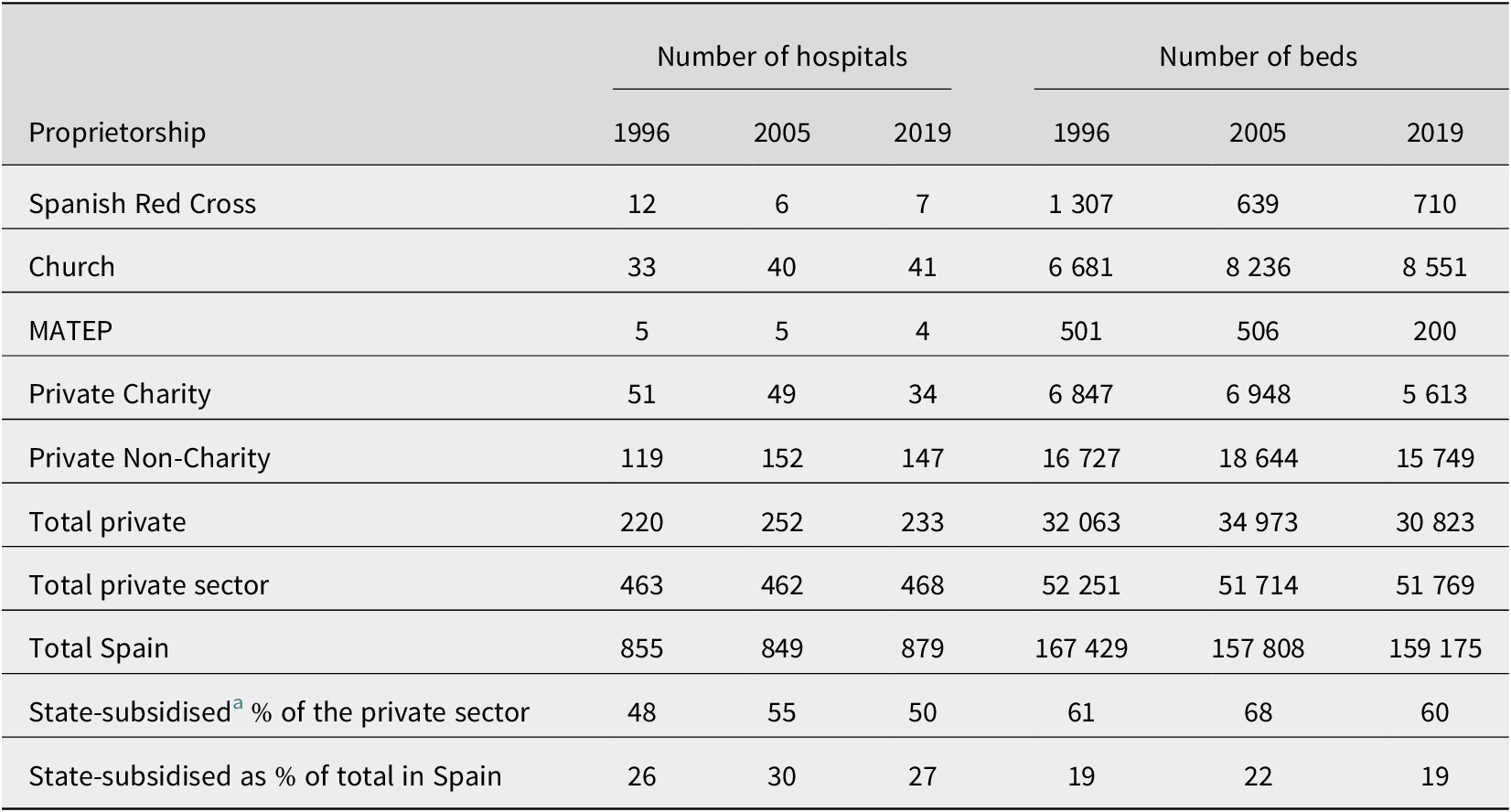

In this respect, it must be borne in mind that after the passage of the LGS and the devolution of health care responsibility to the autonomous communities, there was an increase in the number of agreements signed with private hospitals. Thus, from the 1990s, around 60% of the beds of private hospitals were included in agreements to provide public health services in exchange for state subsidies in order to treat patients referred from the public health system (Table 4). This evolution evidences the important weight that the agreements with the public health sector have had for the private health care business, which has resulted in a relationship that is more of cooperation than of competition. Overall, almost 30% of hospitals and 20% of the total number of beds available in the hospital sector in Spain over the last 30 years have corresponded to private hospitals authorised and subsidised to provide public health services.

Table 4. Private sector hospitals and beds authorised and subsidised to collaborate with the public health system in Spain by proprietorship

Abbreviation: MATEP, mutuas de accidentes de trabajo y enfermedades profesionales.

a Private hospitals subsidised by the state to provide public health care services.

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of the Catálogos Nacionales de Hospitales, 1996, 2005 and 2019.

Therefore, although the LGS enshrined, as a general rule, direct state management with the public administration’s own staff and resources, the actual situation turned out to be less clear-cut. The legal coverage of this situation was clarified with the three exceptions to this direct management established in article 90 of the LGS. First, it should be noted that the supply of most medicines was through private pharmacies. Second, there were the beneficiaries of the aforementioned mutual funds for public servants that financed health care (Muface, Isfas and Mugeju). These mutuals had not developed their own infrastructure and hired services from private and public companies, then beneficiaries could choose from these provided that they had a current agreement with the national health service. Finally, the LGS established the possibility of signing agreements with the private sector for the provision of services.Footnote 43 This philosophy of collaboration between public and private sectors in the area of health care in general and with regard to hospitals in particular was consolidated with the passage of Law 15/97, of 25 April, on enabling new forms of management in the national health system.Footnote 44

The creation of the main private hospital groups in Spain

The modification of the system of funding health care introduced in the Ley de Presupuestos Generales del Estado for 1989 led, as already mentioned above, to a progressive increase of state contributions to the financing of social security. This increasing state financing via taxes was allocated not only to funding directly managed public institutions, but also to funding private institutions such as employers’ industrial accident mutuals, the mutual funds of public employees or other private health care companies, and including hospitals that had signed the corresponding agreements. The continuance of these hospital agreements reveals the interest of private insurance companies and their hospitals in participating in the distribution of public expenditure, which was to become an essential part of their business. The spirit of participation in the process of obtaining this public money can be found in the numerous reports and declarations of the Instituto para el Desarrollo e Integración de la Sanidad [Institute for the Development and Integration of Health Care; hereinafter IDIS], which classify this source of income as ‘necessary collaboration’.Footnote 45

At their peak, the agreements signed with the mutual funds of civil servants and public employees led to 94% of these public servants being covered by private insurance.Footnote 46 This high number of policies favoured the expansion of PHI companies, boosting the figures of their business. With this guaranteed demand, health insurance companies started to reorganise the branch. The first step involved the reduction of the large number of companies operating in this line. The total number of companies active in the health care branch fell from 243 in 1984 to 132 in 1990.Footnote 47 This initial process of concentration was based on a strategy of reducing the number of companies in the sector by means of mergers involving local groups, igualatorios (doctors’ associations) and companies founded by doctors in almost all provincial capitals, which gave rise to stock companies operating at national level.

Most for-profit private hospitals were founded by insurance companies or doctors’ associations who agreed the provision of services with the insurers. Thus, for example, one of the leading health insurers today – Sanitas – had preferential agreements with Organización CEYDE, S.A. in the 1950s. Later, in the 1970s and 1980s, many insurance companies built or renovated clinics to create their own network. This was the case of Igualatorio Médico Quirúrgico, S.A. in Bilbao, which acquired Clínica Vicente in San Sebastián in 1980, or Asistencia Sanitaria Colegial, S.A., which purchased a hotel in Barcelona in 1989 and converted it into Hospital de Barcelona. In this way, the number of hospital infrastructures owned by insurance companies was increasing, and these hospitals treated private patients and members of mutuals and supplemented this with agreements with the public authorities. Since the 1990s, changes in PHI companies have been conditioned by various factors, two of which are particularly notable. On the one hand, the devolution of responsibility for health care to the autonomous communities. On the other hand, the interest of the national banking sector and international investment funds in Spanish private insurance companies and private hospitals. These two elements have led to a segregation of the hospital business and the creation of large hospital groups in Spain. From the point of view of those running private clinics, the sale of small clinics and the creation of large groups is explained by rising health care costs.Footnote 48

The strategy of introducing new models of hospital management had an important role in the consolidation of the hospital groups. These consisted in separating health care provision from financing.Footnote 49 The model was disseminated in the following years, and by 2000, more than seventy public health bodies were managed privately in Spain. The participation of the private health sector in the management of public health care through different legal forms even reached the point of including total management. Some private hospitals were created with the main aim of signing an agreement with the public health authorities and providing coverage to the beneficiaries of the Social Security.Footnote 50 Galicia was one of the first regions to implement the above changes, followed by Catalonia, Valencia and Madrid under the aegis of conservative governments. These business opportunities stimulated the creation of hospital groups such as Capio, Ribera Salud and USP-Quirón.

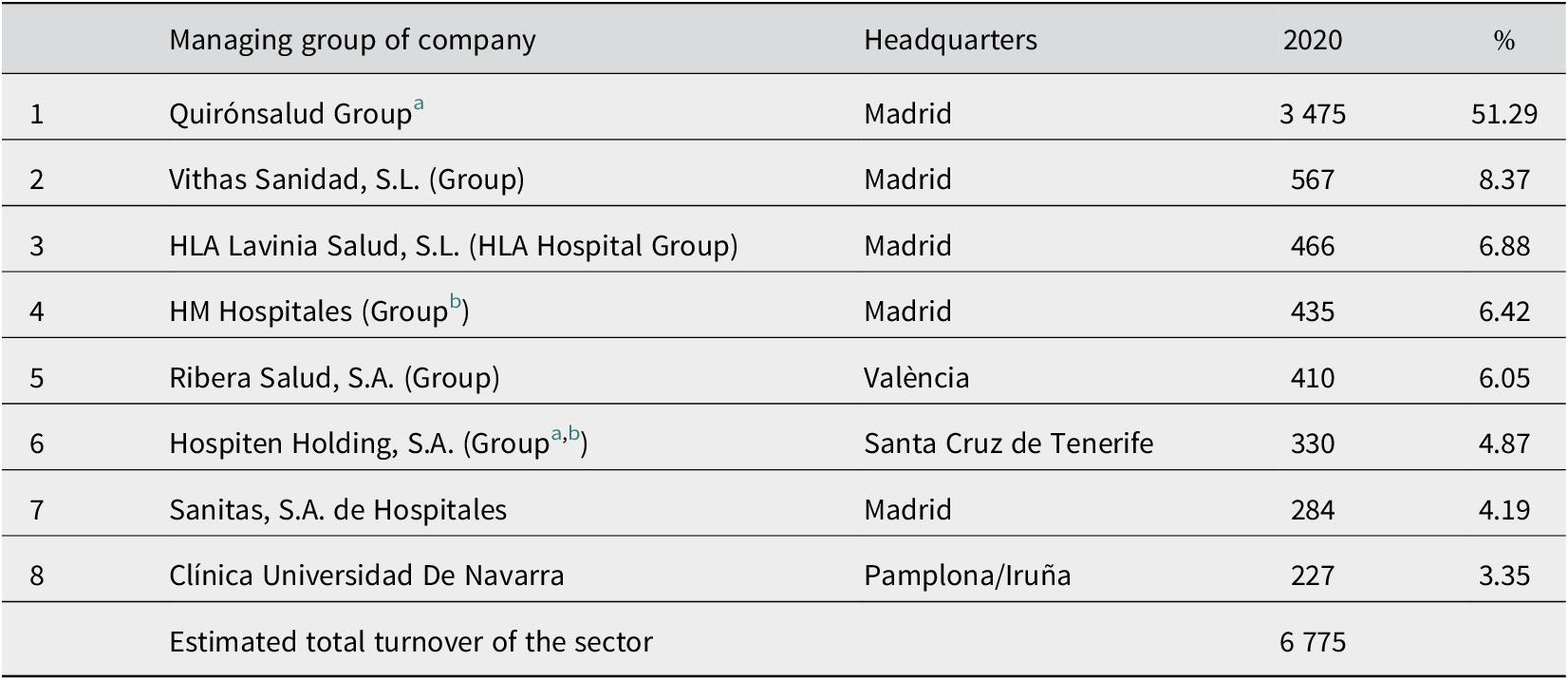

Overall, at the end of the twentieth century, the financial needs arising from technological changes in the area of health care, and the opportunities provided by institutional changes and new political strategies, favoured merger processes and the entry of national banks and international investment funds into the private hospital sector. This complex process led to the emergence of the five large hospital groups that occupy the leading positions in the sector ranking in Spain today: Quirón Salud, Vithas, HM Hospitales, Ribera Salud and HLA.Footnote 51 These five private groups account for 82% of turnover in the sector. This is a very relevant figure if one takes into account that the private non-charitable hospital market in Spain moved 6 775 million euros in 2020 (Table 5). A total of 64% of this income came from agreements signed with insurers, 26% from agreements signed with the public sector and only 10% corresponded to purely private expenditure coming from out-of-pocket payments by patients.Footnote 52

Table 5. Estimated turnover of the main hospital groups 2020 (millions of euros)

Note: The data have been obtained from the Institute for the Development and Integration of Health Care (IDIS), 2021, which warns that its source only provides data for non-charitable private clinics. For this reason, it does not include the turnover of not-for-profit hospital groups such as those belonging to the Church: San Juan de Dios [Saint John of God] or Hermanas Hospitalarias [Sisters Hospitallers].

a Includes income arising from the management of hospitals abroad.

b Includes estimate from DBK.

Source: IDIS, Análisis de la situación de la Sanidad Privada en 2021; available at https://www.fundacionidis.com/informes/analisis-de-situacion-de-la-sanidad-privada/sanidad-privada-aportando-valor-analisis-de-situacion-2021.

It should be pointed out, however, that there are a number of large hospital groups that are excluded from this classification because they are owned by the Church or another kind of private charity in the form of foundations. If the ranking by number of hospital beds is considered, one can see that first position is occupied by the Orden Hospitalaria de San Juan de Dios [Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God] with thirty-three hospitals operational and a total of 8 312 beds, and the Hermanas Hospitalarias del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús [Sisters Hospitallers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus] are in third place with fifteen hospitals and 4 591 beds. There is little information available on the turnover of Church hospitals (Table 5).Footnote 53 Through religious orders and movements, the Church controlled more than fifty hospitals in Spain in 2020, with around twelve thousand beds, which accounted for 7.3% of the total amount. This hospital network has a long history (Tables 3 and 4). Although in theory these hospitals compete with private companies, in most cases, they are identified as non-profit making entities, which gives them important tax advantages. Despite this condition, they generate significant income, partly deriving from agreements signed with the public authorities and insurance companies.Footnote 54 This situation has generated a certain amount of unrest among business groups in the sector who question whether, for Church hospitals ‘with private ownership, enormous revenue and a national health system that treats the entire population, it is logical that they continue to enjoy special conditions with respect to the competition’.Footnote 55

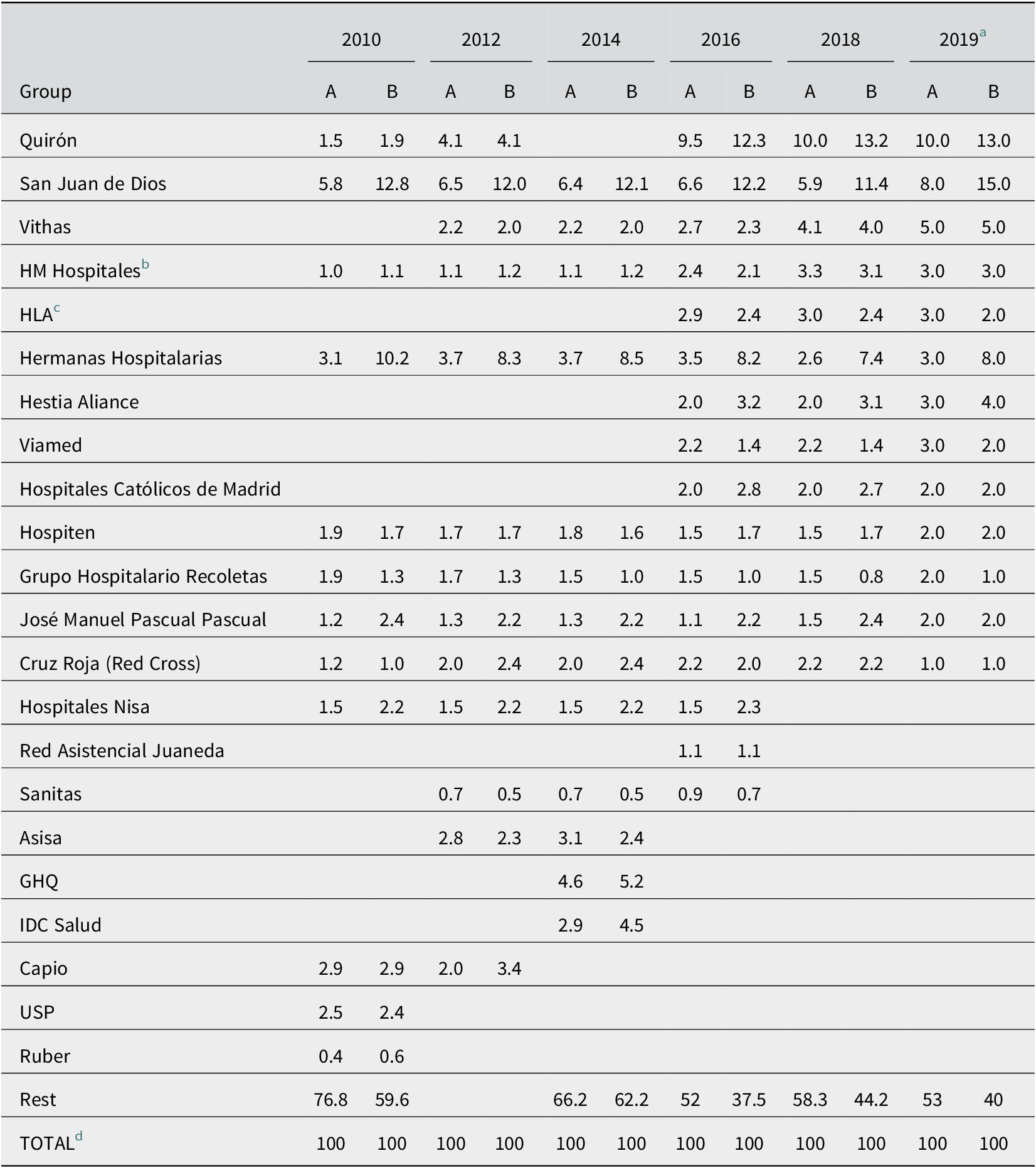

Overall, in 2019, thirteen hospital groups concentrated 43% of private hospitals in Spain and 55% of the beds of the private hospital sector (Table 6). The trend towards concentration and increasingly large companies in this area seems clear, which gives these large groups greater market power and greater capacity to exert pressure when negotiating with the public health system.

Table 6. Private hospital groups by market share of hospitals and beds in Spain

Note: A: market share hospitals (%); B: market share beds (%).

a The information referring to 2019 is provided in the reports for both 2020 and 2021, and this last source has been used due to being more up to date.

b HM, Hospital de Madrid, S.A. constituted on 23 December 1989. Archivo del Registro Mercantil de Madrid, inscripción 1, tomo 134, fs. 149-60, June 1990.

c HLA LAVINIA SALUD S.L. constituted in June 2015 by Asisa insurance company as sole proprietor. Archivo del Registro mercantil de Madrid, inscripción 1, tomo 33688, M-606437, fs. 80-4.

d The sum of the columns does not add up exactly to 100. This is due to the rounding of decimals used in the source we have utilised.

Source: Análisis de Situación de la Sanidad Privada. IDIS report for the years 2021, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013 and 2011.

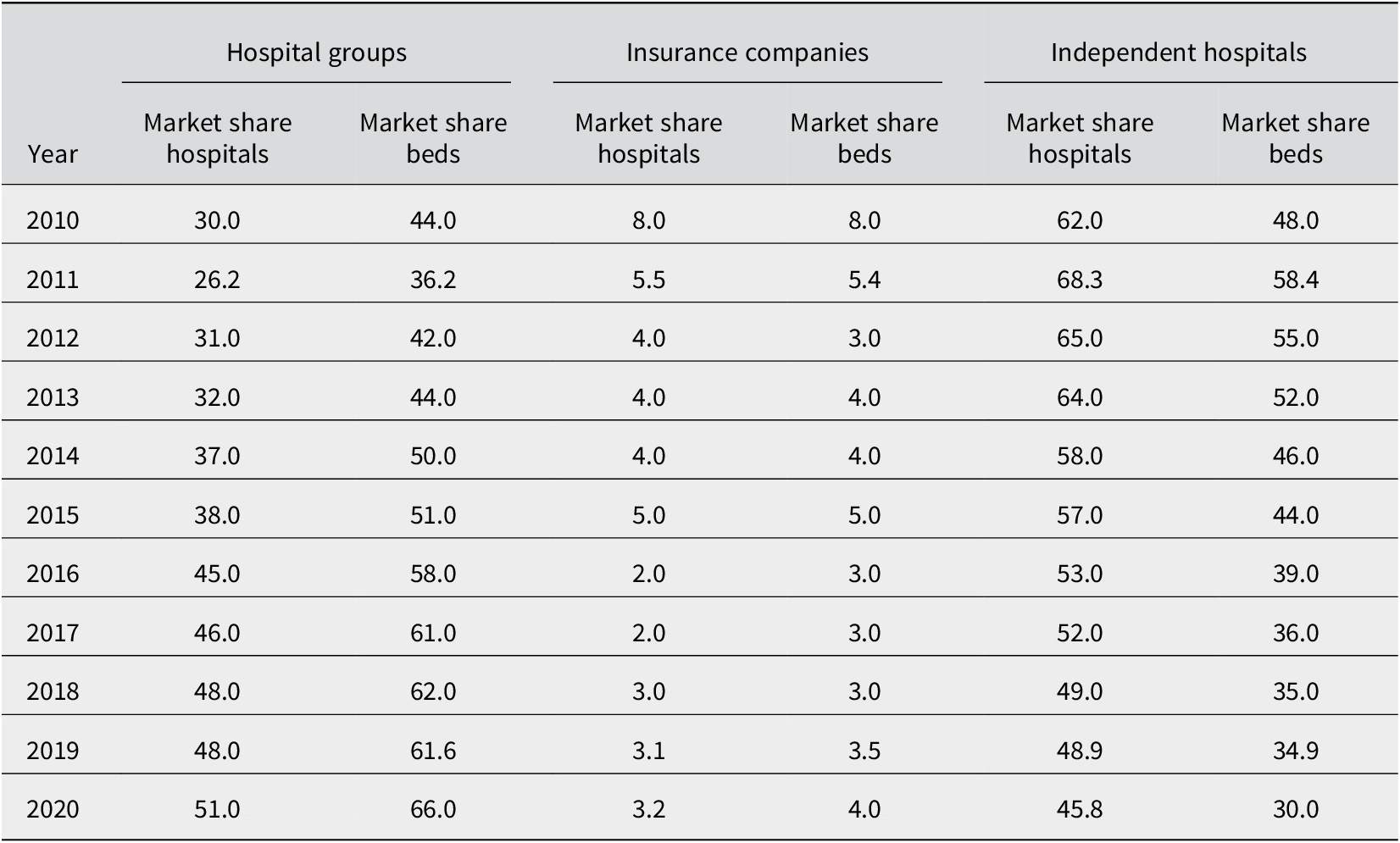

As a whole, the private hospital sector in Spain is characterised by the presence of a number of actors that may be classified in three large groups: hospital groups, hospitals belonging to health insurance companies and independent hospitals. The IDIS report shows that the hospital groups account for 51.4% of private hospitals and 64.3% of private beds available in Spain.Footnote 56 The insurance companies, for their part, have 3.3% of private hospitals and 3.5% of beds. Meanwhile, independent hospitals and clinics account for 45.3% of private hospitals and 32.2% of beds (Table 7).

Table 7. Distribution of private hospitals and beds in accordance with the main actors (in percentages)

Source: Análisis de Situación de la Sanidad Privada. Informe IDIS, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021.

Within this map, over the last two decades, there has been a clear process of concentration of private hospitals by large hospital groups that control the ownership of an increasing number of hospitals. Their market share in terms of both number of hospitals and number of beds grew by twenty points between 2010 and 2020.

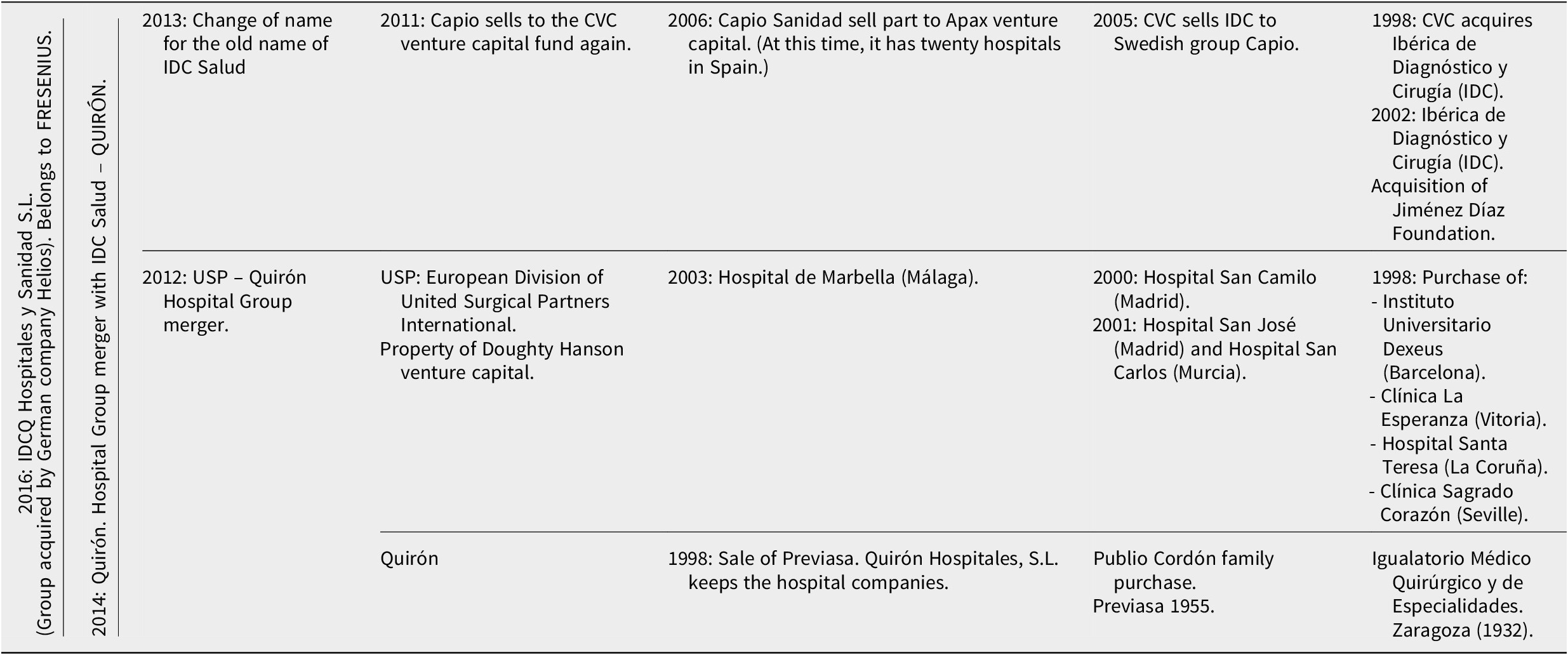

In order to understand the formation of these groups in the long term, we shall focus on the historical creation of two leading groups: Quirón and Vithas. This process is complex in the case of the Quirónsalud group, which has undergone enormous changes, especially since 2012 (Table 8).Footnote 57 The origins of the company date back to the foundation of Igualatorio Médico-Quirúrgico y de Especialidades in 1932 in Zaragoza, made up of a group of doctors with coverage limited to the local area. In 1955, Publio Cordón purchased the company, which then became Previsión Sanitaria, S.A. The company’s first clinic was opened in 1957. An important landmark for its growth was the agreement with Muface, which at the beginning of 1977 obliged the company to operate throughout the whole country. The insurer was in the hands of the Cordón family until its sale to the DKV group in 1998, which disposed of the health services provision business and just kept the Quirón hospital group.Footnote 58 Its rapid growth soon attracted venture capital funds such as the multinational Doughty Hanson, which entered the company’s capital and, in 2012, merged the company with USP Hospitales.

Table 8. Historical transformations of the IDCQ Hospitales y Sanidad S.L. group (QUIRÓN)

Source: Prepared by the authors on the basis of data from the Archivo del Registro Mercantil de Madrid and press news articles.

USP Hospitales had been formed in Spain in 1998 as a European division of United Surgical Partners International under Gabriel Mas Furroll, its president and managing director, and acted as a private and independent hospital group until the start of 2010. A month and a half before the merger with Quirón, Doughty Hanson had acquired USP Hospitales from Barclays and the Royal Bank of Scotland for 355 million euros. These banks had taken control of USP when CINVEN, its previous owner, was unable to meet its debts. This transaction was completed by Doughty Hanson & Co alone, before the merger with the Quirón group, in order to avoid problems with the Competition Commission.Footnote 59

In 2014, the investment fund CVC, owner of IDC Salud, got involved and replaced Doughty Hanson as the leading shareholder of Quirón. In June 2014, a merger agreement was reached between IDC Salud (previously owned by the Swedish group Capio) and the Quirón hospital group, which gave rise to the Quirónsalud hospital group.Footnote 60 Ibérica de Diagnóstico y Cirugía (IDC) had been created in the mid-1990s, with the doctor and entrepreneur Víctor Madera at the helm. It was acquired by the powerful investment fund CVC in 1998, although Madera continued running the company and based his growth strategy on the outsourcing of public health services.Footnote 61 In 2002, it became the leading shareholder of the historical Jiménez Díaz Foundation in Madrid. In 2005, CVC sold IDC, which had now become the leading private health manager in Spain by turnover, to the Swedish group for three hundred million euros.Footnote 62 One year later, the American venture capital fund Apax took over Capio for two thousand million euros. In 2011, CVC bought back the Spanish unit of Capio for nine hundred million euros, went back to using the name IDC and maintained Víctor Madera in charge of the management of the hospital group.Footnote 63

Within this framework, in 2015, an important business concentration operation took place with the registration in the registro mercantil [registrar of companies] of a proposed merger by takeover, with Quirón Hospitales, S.L. as the acquiring company and seventeen companies domiciled in Madrid, Barcelona, Zaragoza, Bilbao and Vitoria as the companies being acquired.Footnote 64 The result was the foundation of IDCQ Hospitales y Sanidad S.L., which started operating on 26 June 2015.Footnote 65 In February 2021, Idcsalud Holding, S.L.U. (Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada Unipersonal; that is, a single-member private limited liability company or SUP) was acquired by Helios Healthcare Spain, S.L.U. and, then, this company became the sole shareholder of IDCQ Hospitales y Sanidad S.L.U.Footnote 66 It should also be pointed out that the main shareholder of the Fresenius group is owned by a non-profit foundation called Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, whose main objective is the development of medical and humanitarian projects.Footnote 67

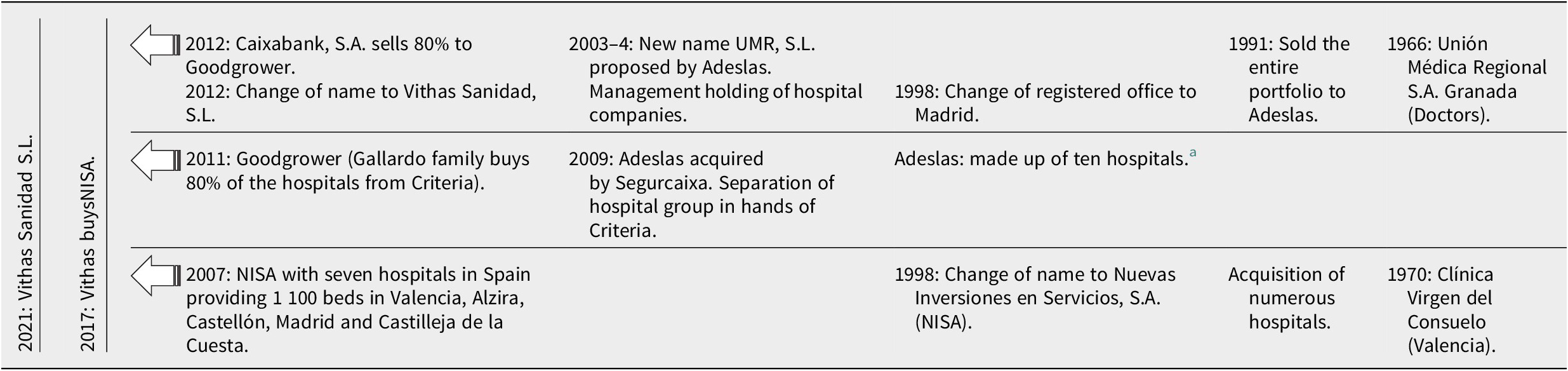

Vithas, for its part, second in the ranking by turnover in 2021, has followed a similar process. The historical creation of this group has been determined by the final union of three business lines: the hospitals of Adeslas insurance company, acquired by Caixabank in 2009; the Goodgrower group, an investment group created in 2008 by the Gallardo family (founder and controlling shareholder of the Catalan pharmaceutical group Almirall) to invest in the health sector and the NISA group, acquired in 2017.Footnote 68 The process started in 1966, when Unión Médica Regional, S.A. was founded in Granada as a health insurance company. The nineteen founding partners were all doctors, except for an insurance agent and a lawyer. The company was created with a capital of one million pesetas distributed in fifty-five shares per partner, except for the lawyer who only acquired ten.Footnote 69 Adeslas became a shareholder in 1986, and went on to become the main shareholder by acquiring its entire portfolio in 1991,Footnote 70 when its name was changed to UMR, S.A. In 2003, a capital increase proposed by Adeslas was accepted and it now became UMR, S.L., a holding of Adeslas, which acted as manager of the hospital interests of the parent company.Footnote 71

When SegurCaixa, belonging to the bank holding company Caixabank, acquired Adeslas in 2009, it chose to separate and dispose of its hospital assets. Adeslas had participated in the concentration process in this branch through the acquisition of local companies from 1991. This path had coincided with the entry of foreign capital into its shareholding, when the French group Méderic acquired 45% of its capital.

However, when VidaCaixa Adeslas sold its non-life insurance business to Mutua Madrileña for 1 075 million euros, also in 2009, it excluded a group of ten hospitals that it put up for sale separately (Table 9). These hospitals together had around one thousand beds, and, in 2009, they were being used by over one and a half million patients. These hospitals then went on to depend on a subsidiary wholly controlled by Criteria. What the sale to Mutua Madrileña did involve included sixty-five dental clinics, thirty-two medical centres and the public–private concession for the use of Hospital de La Ribera in Alzira.Footnote 72

Table 9. Historical transformations of the VITHAS group

a The hospitals were: Ntra. Sra. de Fátima (Vigo), Santa Catalina (Las Palmas), Ntra. Sra. La Salud (Granada), Nra. Sra. de América (Madrid), Virgen del Mar (Almería), Perpetuo Socorro (Alicante), Parque San Antonio (Málaga), Montserrat (Lleida), Santa Cruz (Tenerife) and San José (Vitoria).

Source: Archivo del Registro Mercantil de Madrid and press articles.

In 2012 UMR, S.L. changed its business name to Vithas Sanidad S.L. due to its acquisition by the Gallardo family (Goodgrower), which in turn had acquired the hospitals of Adeslas after its takeover by SegurCaixa.Footnote 73 The investment company Goodgrower had acquired 80% of the hospitals from La Caixa in 2011, which kept 20% within its Criteria CaixaHolding, and relaunched the hospital group with this new brand.Footnote 74 Later, in 2017, Vithas acquired 100% of the Valencian company NISA,Footnote 75 of which it already owned 45%.Footnote 76 The origins of the NISA group date back to 1967, when a group of doctors formed the company Clínica Virgen del Consuelo S.A. in Valencia, inspired by the lack of private health care facilities in the city. It started operating in 1970. In 1991, the company acquired Hospital San Juan de Dios, which was renamed as Hospital Nisa Valencia al Mar. In 1998, the name of Clínica Virgen del Consuelo S.A. was changed for the present name NISA, an acronym for Nuevas Inversiones en Servicios, S.A. In 1993, Hospital Nisa 9 October was inaugurated, also in Valencia. In 1998, Hospital Nisa Aguas Vivas was incorporated into the network. In 2003, Hospital Nisa Rey Don Jaime was inaugurated in Castellón de la Plana.Footnote 77 In 2007, Hospital Nisa Sevilla-Aljarafe, in Castilleja de la Cuesta,Footnote 78 and Hospital Nisa Pardo de Aravaca, in the Aravaca neighbourhood in Madrid, were opened to the public.Footnote 79 In 2010, Nisa inaugurated the Centro de Daño Cerebral Nisa Vinalopó, a drain damage centre linked to Hospital Nisa Aguas Vivas, and, in 2011, Centro Médico Nisa San Bernardo was opened in the centre of Seville. In January 2017, 100% of Hospitales Nisa S.A. was purchased by the Vithas Group.Footnote 80

This purchase transaction reinforced the Vithas Group’s position as the second group in the sector and enabled it to earn an overall income in excess of five hundred million euros. With a significant presence, above all, in Madrid and Valencia, it has nineteen hospitals, twenty-five specialised centres and almost 6 800 employees.Footnote 81 After these years of expansion, the Gallardo family bought the part held by CriteriaCaixa in 2021, now having full ownership of the entire hospital group.Footnote 82

Conclusions

Private health care in general has experienced an increase in activity in Europe, especially in its role as a supplementary provider of public health coverage in recent decades. This paper has shown that, as a result of this process, modern health care markets are a mixture of public and private power. Within this framework, the weight of private hospital groups has also been on the rise. On the demand side, the factors that have driven this process have been the reduction in public spending, the privatisation of public health services, tax incentives for private insurance and changes in the population’s consumption patterns. On the supply side, there has been growing interest in the health care industry among the banking sector, investment funds and general insurance companies.

As regards the case of Spain, the hospital companies have consolidated thanks to the demand generated by private insurance companies to cover both their private patients and those linked to the different mutual funds for public servants, the agreements with the Social Security and the public health institutions created by the autonomous communities, and also thanks to the management of publicly owned hospitals through foundations, from which they obtain enormous profits without direct public control. Other data should be taken into account, such as the percentage of public health expenditure that is allocated to the agreements with the private sector. The private hospital and health care groups, therefore, generate their business thanks to private demand, but they participate in public demand, in which they aspire to grow. In 2017, agreements with private health centres accounted for 11.2% of total public expenditure on health.Footnote 83 The lobbies of the sector, such as IDIS in Castellón de la Plana,Footnote 84 defend the virtues of this collaboration in all private and public circles.Footnote 85

This situation has attracted national and international capital (investment funds, the banking sector and insurance companies), which, with a clearly speculative objective, is investing in the growing health sector, buying and selling its shares in hospital companies with the aim of making large profits in the short term.Footnote 86 Independent hospitals are losing ground in the market of health coverage provision, whereas the large groups are gaining weight, concentrating hospitals and beds and modifying the historical tradition of dispersion and independence of local and regional companies in the hands of doctors from the area, creating a monopoly controlled by financial capital. Moreover, these groups are also diversifying into other lines of business such as care homes for the elderly and dental clinics, other highly profitable niches of the health care business.

These changes raise numerous questions on the future of the sector. What will be the place of medical and health criteria when these groups need to take strategic decisions? What will their contribution to public health issues that do not provide short-term profitability be? Will this situation lead to long-term increases in the costs of health insurance, as is the case in some countries where the commercialisation and commodification of health care is a reality forged by historical tradition? All these questions need to be debated over the coming years in the field of the history of medicine because they are key issues for our welfare.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation – State Research Agency – for the project entitled ‘The historical development of private sector hospital companies in competition and collaboration with the public sector: Spain from an international perspective (1920–2020)’, Ref. PID2021-122699OB-I00. Funding for open access charge: Universidade da Coruña/CISUG.

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.