Introduction

Immigrant bodies have always evoked fear and anxiety in host populations for a variety of reasons ranging from suspicions about the diseases they potentially harboured to the strain they placed on local medical services. Ethnic groups were problematised if they travelled in large numbers and if they exhibited behaviours that were unusual. Biopower, the term Michel Foucault applied to the development of ‘mechanisms, techniques and technologies’ to control bodies living and dead, gained positive momentum around the world in the nineteenth century through, for example, legal obligations to register births and deaths, and the introduction of compulsory smallpox vaccination and the notification of infectious diseases.Footnote 1 Through such mechanisms, the relationship between medicine and the law was copper-fastened and a medico-legal domain was was more firmly established.

In this article, I contend that limited knowledge of medico-legal dictates often brought poor Irish immigrants into conflict with public health authorities in New York and Boston, and I trace perceived errant behaviours to the inexperience of healthcare prior to departure. My primary interest is in the medicalisation of maternity, which forms part of what one might call a universal migratory adjustment pattern and therefore is not unique. For instance, Bourdelais argues that in modern-day Britain, the pathologisation, or description in medical terms, of the body of the mother continues to be the most powerful social determinant of change.Footnote 2 There are several working definitions of what medicalisation is, and Peter Conrad’s succinct definition of ‘using medical language to describe a problem, adopting a medical framework to understand a problem, or using a medical intervention to “treat” it’ applies well to the era we are dealing with.Footnote 3 Engaging with medicalisation in the migratory context forced women, particularly those of Roman Catholic and rural origins, to become literate in a medico-legal sense and represented a paradigmatic shift in the ‘modalities’ of colonial, denominational and patriarchal power they were accustomed to in Ireland. Here, I make the case that thematic and empirical approaches combined with prosopography (collective biography), and the prisms of gender, cultural history and migration studies can help to provide new insights into the historical relationships Irish immigrant groups had with hospitals and dispensaries in the cities of New York and Boston.Footnote 4

From a methodological perspective, the study of some American hospital records is subject to the terms and conditions of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) 1996 and, if the hospital is a ‘covered’ entity, data must be de-identified. As Susan Lawrence’s Privacy and the Past shows, the law has restricted access to the historical records of functioning hospitals and has caused some problems for researchers.Footnote 5 To illustrate the problems that Lawrence identifies, I adopted a thematic case study approach to records held in the Cornell Weill Archives (CWA) and the Center for the History of Medicine (CHM), Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University. The latter holds several bodies of records, some of which are of long-closed medical facilities and are therefore non-covered entities in terms of HIPAA privacy and confidentiality clauses. CHM also holds Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) records, a covered entity. CWA holds the historical records of a functioning hospital, New-York Presbyterian, and, although some admission records date from the 1850s, it adheres to HIPAA in a blanket fashion. Susan Lawrence has argued that technically early historical records fail the test for inclusion under the privacy and confidentiality clauses of ‘covered entities’, but researchers must abide with conditions of usage in both centres.Footnote 6 In 1977, Gerald N. Grob suggested that manuscript census returns be used in tandem with civil registration of death to harvest personal information and pointed out that ‘Hospital records, which in many cases preserve relatively complete pictures of patient populations, still await systematic use’.Footnote 7 Since his recommendation, HIPAA has forced a retrospective classification of some historical medical data as ‘dangerous’ and, in an era, when data linkage technologies and artificial intelligence are advancing apace, the opportunity to develop innovative methods and create meaningful linkages between these and other ‘safe’ historical big data, like civil registration, census and immigration records has and is being lost.Footnote 8

Modern medicine and the law acted in tandem to count, manage and, in times of contagion, to restrict the movement of bodies, but for some immigrant groups, like the Irish, biopower dictates, like civil registration of births and deaths (introduced in 1864), were either entirely new concepts that they were ignorant of, or chose to ignore out of distrust. Power manifested in Ireland primarily in British administrative terms and was articulated through civil, religious and patriarchal structures. Biopower produced enormous amounts of data, much of which is available freely online and they offer enormous potential for data linkage, longitudinal analysis and life course studies. How the poor engaged with biopower, or not, is an important socio-economic indicator. To place the potential of American hospital records in context, I adopt a transnational approach and contend that it is important to develop understandings of the development of biopower in Ireland to trace how the populace responded to it and how that response in turn underpinned Irish immigrant behaviour.Footnote 9 Travel documents like passports or national identification cards were not a requirement during this era of mass migration. Prospective migrants from rural Ireland rarely featured in official records until they emigrated, they were listed as passengers on ships and these aggregate figures were collated on departure and arrival.

The Irish provide a useful example of an immigrant cohort, who presented as a burden to public health authorities in the American metropolis. Using personal data provided by immigrant women to hospital authorities this article provides an overview of how they acculturated medically and how attitudes towards the Irish-born changed during the period 1860–1911. Irish-born was the only criteria for inclusion in the samples I have used here, although it is worth noting how some hospitals continued to record ‘Irishness’ in second and third generations. By tracing how Irishwomen engaged with maternity hospitals in New York and Boston, I show how their levels of medico-legal knowledge impacted the ways in which they chose to self-identify. In so doing, this article also provides a flavour of how the socio-economic profiles of the immigrants and their behaviours changed over the period.

Few migrants were prepared for life in the new world, and this article begins by discussing the mixed medical economy in Ireland. It then traces popular American discourses on patterns of Irish migration, fertility and behaviours and outlines some of the medical services that were established to deal with the poor in general. Through an exploration of their engagement with dispensary and hospital settings it establishes how the Irish became problematised in the migratory setting. The contours of migration flows made Irish immigrants a threat to public health in the cities of New York and Boston. The Great Famine (1847–52) accelerated the rate of Irish emigration with an estimated 1 million, largely pauper, emigrants going to America alone. This article takes 1860 as a starting point to coincide with the stabilization in the numbers of Irish Roman Catholics going to North America in the immediate post-Famine period and 1911, when the Dillingham Commission on immigration, formed in 1907 ‘in response to growing political concern about immigration in the United States’, published its findings.Footnote 10 Difficulties with quantification notwithstanding, it is estimated that between 1850 and 1910 some 3.6 million Irish emigrated to America alone.Footnote 11 Enda Delaney puts this in more startling demographic terms in stating that there were nearly as many Irish-born ‘outside the country than in it’ by the close of the nineteenth century.Footnote 12 In the final sections, crudely codified personal data (full forename and surname initial) from admission registers are used together with excerpts from the annual reports of New York and Boston hospitals to discuss the importance of medical records to the history of immigration. It concludes by offering a brief commentary on the methodological issues that present when working on HIPAA covered and non-covered entities.

Pre-departure Irish

Engagement with healthcare structures varied from region to region in Ireland: whether or not immigrants were from urban or rural Ireland, how carefully non-compliance with civil registration was policed and proximity to medical services dictated the level of experience they might have had with what we now recognise as ‘modern medicine’. Most immigrants came from remote parts of the West of Ireland, where the culture of migration was long established. The rural post-Famine Irish immigrant had little experience of the structures of hospital or dispensary care, which were located in towns and villages. This is partially because of the way in which both systems developed in Ireland. The 1851 Medical Charities Act, Ireland consolidated the ad hoc network of voluntary hospitals and dispensaries to create a ‘free’ public healthcare system for the poor.Footnote 13 Convenience triumphed in the early 1850s and unfortunately, it was grafted onto the newly established Poor Law Union (PLU) or ‘workhouse’ system, which as Laurence M. Geary states ‘was unreservedly hated’ by the poor.Footnote 14 The Act first aimed to create order and subdivided the country into 723 dispensary units, which were serviced by a doctor and, as the century progressed, some employed nurses with midwifery skills. Until the 1898 Local Government Act, the management of the dispensaries was overseen by non-medically trained local committees comprising poor law guardians and ratepayers, who not only scrutinised the daily management of the operation, but also had a hand in deciding who received access to care.Footnote 15

In practice, poor people had to plead their case for treatment to the non-medically trained local elite or PLU employees. The successful outcome was categorised using a black ticket, which permitted treatment at the dispensary or a red ticket, that allowed treatment in the home. Ruth Barrington has argued that the latter became such a highly abused commodity that it was colloquially known as a ‘scarlet runner’.Footnote 16 So called ‘union hospitals’ were located in local workhouses and the admission criteria were similar, a parading of one’s destitution to a combination of local relieving officer, dispensary doctor and to a lesser extent poor law guardians was a pre-requisite. For gendered, class and denominational reasons, it was not uncommon for poor rural people to die without ever having availed of medical assistance to which they were entitled.Footnote 17 When civil registration of births and deaths was introduced as well as compulsory smallpox vaccination in 1864, it too was mapped on to the PLU dispensary system. It forced the engagement with local dispensary doctors, and many in rural areas ignored their obligations to register births and deaths, or indeed to vaccinate their children. Deborah Brunton’s research has raised questions about Irish claims to smallpox eradication in the 1880s and contends that it was based on incomplete birth statistics.Footnote 18 In 1900, Dr Thomas Croly, the long-standing dispensary doctor (1878–1916) on Achill Island, which had a population of about 5 000 people and was a major ‘sending community’, wrote to the Westport board of guardians to complain about 310 vaccination defaulters in his district.Footnote 19 Death registrations were also incomplete in the West of Ireland until relatively recently.Footnote 20

A mixed medical economy was in operation in Ireland throughout the period under review and by the close of the century patent medicines had made a strong impact. Traditional practitioners like ‘wise women’, herb women, handywomen and magical healers were long established and in operation for centuries. Often their claims to curative powers were embedded in and legitimised by the Irish landscape, for example, the use of local herbage, holy wells and archaeological structures like standing stones. They usually did not emigrate, and, unlike local dispensary doctors who also carried out private practice for fee-paying patients, they were paid in kind. In a barely fluid economy that relied heavily on credit, traditional practitioners offered formidable competition to the dispensary system.Footnote 21 A 1910 survey found that most unions retained these strong traditions: out of the (then) 158 PLUs, 137 had unqualified practitioners in operation.Footnote 22 Quacks, cancer curers and unqualified chemists prescribing concoctions making spurious claims to curative properties were found in most unions. Strong folk belief in the supernatural had not abated either and charms were in widespread use to cure erysipelas. The Union of Ballina reported how a recent case of ‘bonesetting’ had ‘disastrous results’. Three years prior, in nearby Ballinrobe, an anaemic young girl died following treatment by ‘a tramp claiming medical knowledge’ – he was prosecuted and sentenced to 2-year penal servitude. The report used adjectives like hopeless, extreme, unnecessary and violent to describe the ‘torture’ afflicted by bonesetters and ‘handywomen’ (untrained midwives) from Castlebar in the north west down to Youghal in the south.Footnote 23 In Clonakilty, West Cork, handywomen were accused of presiding over ‘fatal results’, and people were noted as seeking ‘advice for their aliments through the columns of newspapers’.Footnote 24 In Ballymena, County Antrim, the report found that ‘a properly equipped medical man is not called in until death is imminent’.Footnote 25

Irish migration

Late nineteenth-century New York and Boston were important cities to many Irish people emigrating for new opportunities and, of course, to escape poverty. It was their notable urban presence that caused several anxieties throughout the period I examine and, according to Kevin Kenny, it ‘came to symbolize immigration and its attendant problems. They, and not the Germans, became the primary target of nativist, or anti-immigrant, sentiment’.Footnote 26 The preface to the 1860 American census remarked that the calibre of migrant had reduced considerably and, it commented, how former European migration was characterised by those disaffected by religious bigotry who comprised ‘a class of persons distinguished for high moral excellence’.Footnote 27 New York’s foreign born population was nearly one million (998 640) in 1860, of which a colossal 49.73% (498 072) were Irish, as against 25.59% (256 252) from ‘German States’.Footnote 28 The Irish were by far the most numerous ethnic group, comprising almost 13% of the population, as against 75% considered ‘native’.Footnote 29 This was a source of concern; the census noted that the Irish tended to remain in their original urban settlements and that they were endogamous in marriage patterns.Footnote 30 Their static nature caused the New York Times to report in 1873 on:

the inability of Irish immigrants, through poverty, to go westward immediately after landing. It would be perfectly safe to say that two thirds of all those who came in the past thirty years were born either on farms or in rural villages. Previous to emigration most of them had probably never been half a dozen times to the city.Footnote 31

Like the 1860 census, the Dillingham commission on immigration noted that in 1911, the Irish, who were largely of rural origins, still predominated in urban areas. It wrote ‘… their concentration in the Eastern States, where farming is a relatively unimportant pursuit, and their preference for city life makes the percentage of farmers in the total number of Irish in the United States comparatively small’.Footnote 32 An equally worrying factor for the American authorities was, as Guinnane et al have found that their marital fertility was higher than the native born.Footnote 33 Recent research by Dylan Connor challenges the idea that those who left were the ‘best men’ by comparing various data on those who stayed and left. He found that those who left were more likely to be unskilled, of rural origin and with lower literacy levels.Footnote 34 Connor’s findings tally neatly with Thernstrom’s earlier observations about the Boston Irish whose upward mobility in second and third generations was a much slower process, not only than that of the native born of similar class, but also when compared with those of British or West European origins.Footnote 35

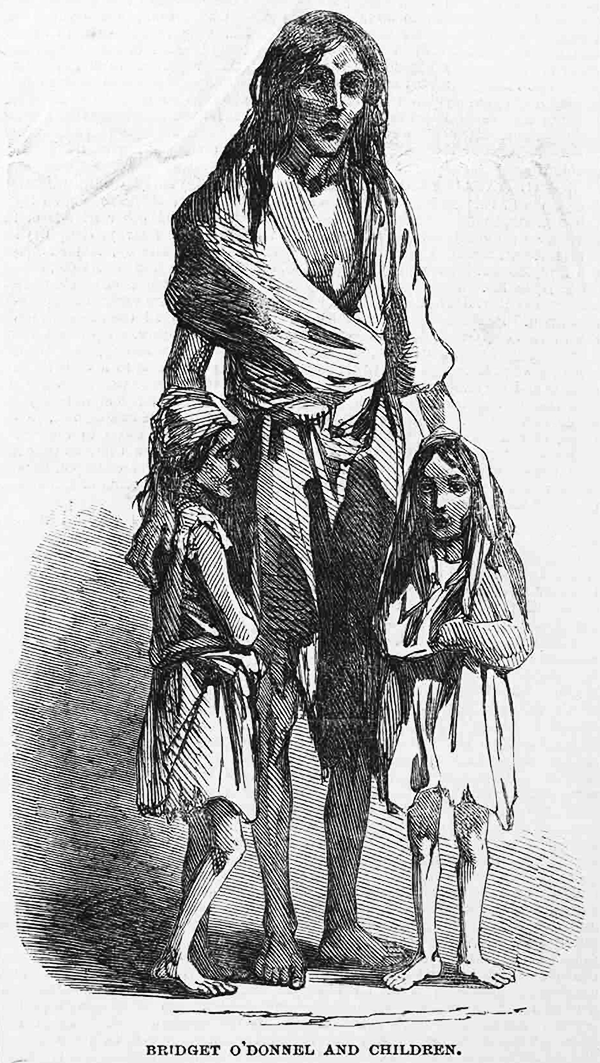

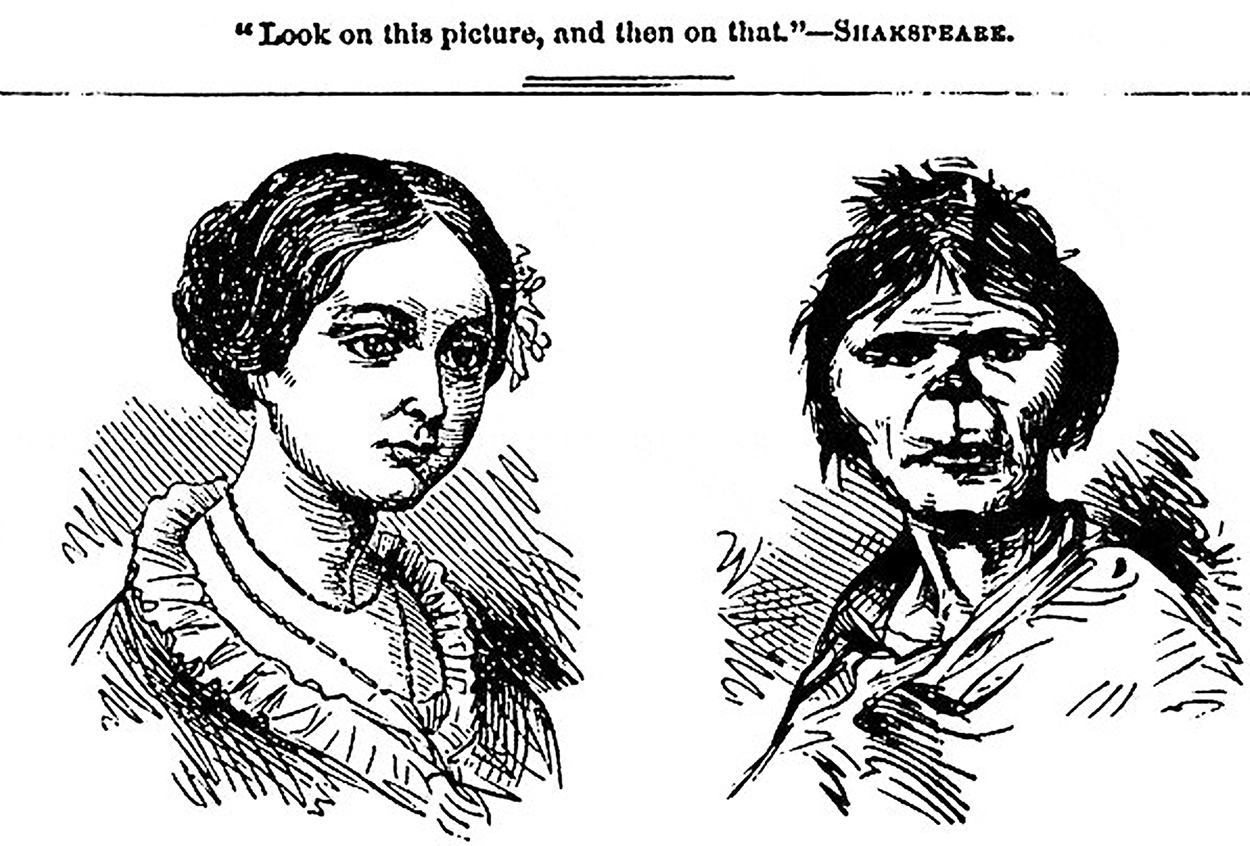

Kevin Kenny cautions against the use of extreme imagery to show how the Irish were simianised in the popular press and argues that it was among the many ways that Irish people were viewed.Footnote 36 Nonetheless, the sheer volume of Irish caused lampooning in the British and American illustrated press.Footnote 37 It lent credence and legitimacy to the idea of Irish alterity, which provided a convenient focus for nativist ire. Receiving cities of New York and Boston understandably suffered from immigrant fatigue and fear of contagion and the image of the pitifully emaciated, and ‘deserving poor’ Famine-victim ‘Bridget O’Donnel' (usually spelled Donnell see Figure 1) published in the Illustrated London News quickly gave way to the simianised, ugly ‘Sally Muggins’ and ‘Bridget McBruiser’ (Figure 2), who according to phrenologist Samuel Wells, occupied the ‘basement mentally as well as bodily’.Footnote 38 Even in their heyday phrenology and physiognomy were discredited, but the Irish were regularly used as case studies particularly in Australia and America, where there were conspicuously located in urban settings in large numbers.Footnote 39 Within these degeneracy discourses the poor female immigrant received considerable attention as both the source of and the solution to public health problems.

Figure 1 Bridget O’Donnel and children.

Source: Illustrated London News, Dec. 22, 1849.

Figure 2 Contrasted faces: Florence Nightingale and Bridget McBruiser.

Source: Wells, New physiognomy, 537.

From a public health perspective, anti-Irish, or more specifically, anti-Irish Roman Catholic, immigrant sentiment was articulated from the 1830s and found repeated expression in the decades that followed.Footnote 40 Alan M. Kraut has shown how the poorly educated ‘low Irish’ were scapegoated in America during the 1932 cholera outbreak. Undesirable traits of Roman Catholicism as well as the intemperance of some immigrants, served to set all Irish people apart and it was easy to transform public panic about disease into scorn against particular ethnic groupings.Footnote 41 When Christopher Crenner applied an empirical approach to the history of medicine, race and medical practice in Kansas City he found similar evidence of ‘Irishness’ being used in derogatory terms. More specifically, his work, which focussed on individual medical settings, found that such applications pertained ‘only to male patients who drank heavily’.Footnote 42 By the late nineteenth century, nativists were zealously adopting ‘germ theory’ to bolster an anti-immigration lobby in America and enjoyed a great degree of success.Footnote 43

Even after the early waves of Irish immigrants had acculturated and gentrified and newer migrant groups like the Chinese and Eastern European Jews became more central to nativist concerns, the old stereotypical links between ethnicity and disease were hard to sever. Indeed, they were easily revived as the vilification in the early twentieth century of asymptomatic typhoid carrier Mary Mallon attests.Footnote 44 How she earned the sobriquet ‘Typhoid Mary’ is well known: it was proven that as a cook she caused an outbreak of disease. She was asked to abandon her profession, but the aging and single Mallon could not survive on the paltry wages of domestic service and laundry work, where she had to compete with younger women willing to work for lesser wages. She started cooking again and was the source of another outbreak. Her errant behaviour apart, Typhoid Mary was the only one of 675 known healthy carriers to be relentlessly pursued by the public health authorities in New York from 1906 to 1932 and effectively incarcerated on North Brother Island for the public good for the 23 years prior to her death.Footnote 45 Her ethnic, immigrant and single status all played a part in the construction of the threat she posed to public health, and that owes much to the conduct of previous waves of Irish immigrants.

Immigrant Irish women

The Irish women I have identified in New York and Boston lying-in hospital records predominantly arrived with very little means. They emigrated in a few different ways, the optimal situation was one where they moved as part of a family group, but most travelled alone. During and in the immediate post-Famine era, it was not uncommon for landlords (who were also poor law guardians) to assist the passage of tenants in arrears to clear estates. In some instances, families mortgaged agricultural tenancies in Ireland to purchase tickets on credit for their most promising able-bodied members, usually aged between 15 and 25 years. This acted as a guarantee until such a time that remittances were received to clear the debt. Fitzgerald and Lambkin argue that short-term stints or ‘seasonal migration’ provided invaluable experience to those who progressed to the ‘migrant stream’ of ‘pioneer, chain, seasonal, step and return’.Footnote 46 For many going to America they travelled directly, so they did not have the benefit of the experience of prior seasonal (short periods of up to a year in Britain picking potatoes), or step (periods of over a year in Britain) migration, many were pioneers or the first chink in their family’s migrant chain and few were likely to return. In other instances, poor law guardians assisted passage either through reuniting family members or indeed instigating a new chain of migration much to the chagrin of the American authorities and to the reputational expense of the previous waves of Irish who had made social gains. Further damage was done to the Irish immigrant profile by the migration of convicts who were ‘released on license’ or in modern parlance, parole, as Elaine Farrell’s work has shown.Footnote 47 Whatever the pathway of travel phased via Britain or direct, as a solo traveller or in a family group, the post-Famine Irish immigrant caused physical and moral anxieties in America.

New York City was no doubt a daunting place for new arrivals of rural origins. Funnelled through Castle Garden and later through Ellis Island the majority of Irish emigrants settled in lower Manhattan or Brooklyn. One literate immigrant from County Down described her bewilderment in a letter home as follows, ‘You can scarcely form any idea of this last place unless you saw it & even then it baffles description’.Footnote 48 Their inexperience of city life did not bode well for early attempts of public health controls in America. Single Irish ‘surplus daughters’ migration was sustained in the post-Famine era and their numbers often surpassed the number of men.Footnote 49 Kerby Miller concludes from his analysis of the New York Irish immigrant statistics that between 1851 and 1910, the sex ratio was equal and in general terms, the median age of Irish women arriving in New York by 1890 was under 20.Footnote 50 As unskilled workers, they had few employment prospects. According to Christine Stansell, New York ‘was full of single women’ in the 1860s, with some 125 women of marriable age to every 100 men.Footnote 51 Of her sample of 400 single working women, she found that 224 were living independently of kin. They crammed into lodging houses with co-workers and in tenements that doubled as ‘all female cooperative workshops’ by day.Footnote 52 Rosner contends that the migrant influxes of all nationalities and the high mortality arising from the inevitable overcrowding that occurred in the tenements had a dramatic impact on the development of healthcare.Footnote 53 Enveloped in a racialised degeneracy discourse the poor, rural, female Irish immigrant received considerable attention as both the source of and the solution to public health problems in the American metropolis.

The vast majority of young Irishwomen emigrating in this period found work as domestic servants. Upward mobility for middle-class households was articulated through the creation of a burgeoning hierarchical domestic sector, and those at the lower echelons could effectively be trained on the job. From the 1850s, there was a huge degree of fluidity and no shortage of employment as ‘the native-born eschewed’ low status work. Andrew Urban argues that in the 1850s Irish women enjoyed certain degrees of ‘racially inclusive settlerism’ that was not later afforded to Chinese migrants, and also contends that those travelling alone were viewed as ‘future members of the nation’s reproductive population’.Footnote 54 When numbers increased, attitudes changed, Vogel estimates that in 1870, 14 000 Irish servants occupied the attics of Boston’s elite homes.Footnote 55 The stereotypical blundering ‘Biddy’ found her niche in domestic service, and earned notoriety.Footnote 56 Owing to its common usage, Bridget (Ireland’s female Patron Saint) and its abbreviation ‘Biddy’ came to be used as derogatory colloquialisms to describe young Irishwomen. Although not as dangerous as her male counterpart ‘Paddy’ (Patrick), the association gave rise to some changing their names to its ancient form of Bedelia or, more commonly, Delia to escape the stereotype.Footnote 57 Faye Dudden argues that Bridget/Biddy came to represent the ‘servant problem’ more generally, despite the fact that domestics of other nationalities were equally problematic. Prompted in part by the pressure to repay debts, they were a feisty lot who advocated for themselves, in order to send home what Dudden describes as ‘staggering amounts’ in remittances.Footnote 58 The employment of Irish domestic servants went in and out of fashion in the decades that followed; by the 1880s, Bridget was the subject of ridicule in the illustrated press and in some lady’s magazines, though by the close of the century her absence in the labour market was lamented by her erstwhile ‘lady’ detractors.Footnote 59

Live-in employment arrangements would have been an attractive proposition for lone-travellers duty-bound to send home remittances. It was also where, as Julie Miller contends, they were ‘vulnerable to sexual involvements’.Footnote 60 Even if relations were consensual, respectable households rarely allowed the prospect for unmarried servants to keep their children. Furthermore, Miller argues that in the absence of close support networks there was nobody to ‘drag laggard or unwilling lovers to the altar’, which she maintains gave rise to the abandonment of infants.Footnote 61 As Doris Weatherford has noted occupationally, domestics ‘accounted for almost half the admittances at homes for unwed mothers’.Footnote 62

By virtue of being unchaperoned young Irish immigrants gave off the perception of sexual availability, which exposed them to potentially dangerous liaisons. Typical of this innocent type was Ellen Maloney, who arrived on 9 June 1874 aged 18 on the City of Brussels. She was registered in Castle Garden in vague terms, parentage unknown, her last place of residence was documented as unknown as was her literacy level.Footnote 63 It seems that she shortly thereafter took up a position as a domestic servant in Brooklyn. Very few travel guides were in circulation for the masses, so it is unclear how prepared Maloney was for her solo travels. The ‘Nun’ of Kenmare’s proscriptive 1872 text which sold tens of thousands of copies, warned Roman Catholic girls about cavorting with Protestants and advised against taking up positions in their households.Footnote 64 Her only advice regarding moral behaviour pertained to advice about matrimony.Footnote 65

No girl should ever meet young men at drinking-saloons, or go to such places. If you do not respect yourself, no one else will respect you. Take care or this. No good man will care to marry a girl whom he sees going to such places.Footnote 66

This is not to suggest that every young Irish domestic servant had a copy of this text or indeed that they were all literate, however, there is little doubt other than the circulation of reproductive knowledge was even more limited than travel literature. Leanne McCormick has cogently argued that in twentieth-century Belfast young Roman Catholic women were less likely than Protestant women to know about contraception or to avail of abortion services.Footnote 67

It is unsurprising that Ellen Maloney’s first sexual encounter had disastrous consequences. It was allegedly forced by John Clyne and ‘through violence’. He agreed to marry her to avoid prosecution for the attack but reneged on his promise. Recognising her potential corporeal shame, Ellen Maloney brought a case against her seducer on the advice of her employer Mrs Moses G. Wilder of 313 Raymond Street, Brooklyn. Footnote 68 Suellen Hoy has posited that in the course of the late nineteenth century middle-class housewives became managers of their respective households, which extended to a protective relationship with employees.Footnote 69 Those associated with the household came to represent it and for such reasons the moral behaviour of domestics came under the purview of employers. In the process of trying to construct a case of previous immoral behaviour Ellen Maloney was medically examined and was clearly traumatised by the affair. She took poison to end her life and her suicide note recalled the trauma of her internal examination: ‘Don’t strip me. Bury me as I am’. Typical of most domestics she appeared to be alone in her travels and was ‘about twenty years’ at the time of her death. The newspaper account detailed how she had left Ireland 18 months prior and was ‘respectably connected’ there.Footnote 70 Newspapers provide other examples of possibly pregnant and unmarried young Irish women committing suicide, but many proceeded to have their children. Sensationalised newspaper coverage lent considerable weight to the idea that immigrants in general and the Irish in particular, were problematic mothers.

The experience of poor, single women from all ethnic origins must have been similar, but where the Irish differed was in the fact that more emigrated alone and were devoid of support networks when income streams were interrupted through unplanned pregnancy or illness. For those with supports they tended to be weak in practical terms as upward mobility was so hard won, and there were rarely extra resources to share. Hobson notes that the Irish were overrepresented in terms of prostitution in the 1860 and 1870s and that unlike trends in sex commerce in Europe almost a quarter of those in New York, Philadelphia and Boston were married. She cites marital breakdown and husbands working away from home on canal and railroad building as primary factors.Footnote 71

Irish immigrants and healthcare

When wealthy Americans were sick in the latter half of the nineteenth century they paid for private healthcare in their own homes. Healthcare services in dispensaries and hospitals were established to meet the needs of the poor, both native and foreign born. They were also shaped by the extent of immigrant knowledge, which had a profound impact on how medical structures developed in cities like New York and Boston. Hospitals were established on a voluntary, or charitable, basis in the nineteenth century for curable, respectable and ‘deserving poor’. Incurables and disreputable types were limited to the almshouses.Footnote 72 The way in which hospital and lying-in hospitals evolved in Ireland was not too dissimilar to America and the admissions process had shared attributes too. In the early years of MGH ‘patients had at first to make written application, then be visited by a physician, then be endorsed by the visiting committee of the Board of Trustees’.Footnote 73 MGH initially ‘resisted admitting the Irish’ in the 1820s; exceptions were made for accidents, but by the 1870s the foreign born made up such a large proportion of the population that the trustees had to open the doors.Footnote 74

A brief analysis of MGH records shows a pre-migration pattern of symptoms present for months prior to seeking medical care for both Irish men and women. With the restrictions imposed by HIPAA it is not possible to conduct further meaningful research on these cases or to link these data to other data types. Nonetheless the following five cases merit mention because they provide examples of the problems posed to public health by the limited medico-legal literacy and subsequent behaviours of the Irish immigrant community. For instance, the case of male patient 1, a married labourer diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis who only sought medical care at MGH when he found himself ‘very short winded’. He was discharged after 10 days, not recovered and his history revealed that he was not deferential: it was discovered that 2 years prior to that he been in hospital at St Barth’s and he ‘went out contrary to physician’s advice’.Footnote 75 Female patient 1 was diagnosed with neuralgia, she presented at MGH with a sore leg as a result of a fall the previous year during which she injured her knee but did not cut it. For the first 7 months she was under ‘someone’s care’ and continued to work. In the 5 months prior to admission to MGH, she had stopped working and applied to various physicians in Roxbury and Boston.Footnote 76 Female patient 2, a widowed domestic suffered for 8 weeks with severe indigestion and in that timeframe ‘she prescribed medicine for herself’. She spent 15 days in hospital during which time leeches and senna were administered for the hepatitis MGH diagnosed.Footnote 77 Widowed domestic, female patient 3 was brought in from Brighton ‘almost dead’. She was unable to give account of herself owing to her weakened state save the fact that she had been subject to ‘attacks’ and ‘that the present attack lasted 8 days’.Footnote 78 She was diagnosed with pneumoniaFootnote 79 but her autopsy, which took place on 29 April 1860, gave no conclusive cause of death.Footnote 80 Male patient 2’s condition was similar, he was brought to MGH in a state of violent delirium, on the second day he was ‘strapped to the bed and talked incessantly’. He died 5 days later, and his autopsy found evidence of third stage pneumonia.Footnote 81

Much like the poor law system in Ireland, the admission criteria for MGH, incorporated deterrent principles for people with varying degrees of literacy. Poor people of other nationalities undoubtedly experienced the same issues, but the Irish populations in both New York and Boston were more substantial, which was why they were singled out as problematic. While some demurred others over-burdened general medical services, after all, it was where nutrition and informal economic supports could be found. This, as Alan M. Kraut has argued, ‘sent shock waves of apprehension through native-born Americans, especially in port cities such as New York where the presence of the Irish was most visible and where sick or disabled newcomers most strained existing medical facilities’.Footnote 82 Immigrant knowledge exchange networks spread the word of sympathetic institutions quickly. Of 2 843 patients treated at the New York Hospital on Broadway and Church Street (Lower Manhattan) in 1863, 1 053 were documented as ‘United States’ in nativity terms, the Irish made up 923. This hospital dealt with general accidents and emergency and routine surgery, but it had agreements with the Commissioners of Emigration and accepted pauper patients.Footnote 83

As Vogel has argued, the type of people who used hospitals had an indelible impact on public perception. Patients were ‘objects of paternalism’ by the ‘non-medical elites’ who established and funded the voluntary hospital system.Footnote 84 Similarly, Rosner argues that private fee-paying patients were discerning and generally avoided hospitals associated with almshouses and prisons like Brooklyn’s Kings County Hospital and Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital.Footnote 85 This undoubtedly frustrated the efforts of trustees when they tried to diversify revenue streams and reduce the reliance on philanthropy. Dispensary services also had to contend with reputational problems once the Irish began to use them. Rosenberg cites how a visiting dispensary physician in Boston pinpointed a dearth in Irish medico-legal knowledge as a primary issue. He noted in 1850 that ‘Upon their habits – their mode of life …depend the frequency and violence of disease. This I am fearful will continue to be the case, since no form of legislation can reach them, or force them to change their habits’.Footnote 86

A perfect storm of religious and moral concerns combined with modern public health campaigns to give rise to the foundation of general hospitals, lying-in hospitals and infant asylums for the poor. Within the discourses of moral hygiene, Irishwomen were singled out and for good reason, they naturally became a primary user of such services. For instance, the Nursery and Child’s Hospital in the City of New York, which was located on fifty-first street near third avenue noted in its third annual report in February 1857 that of its 533 patients since March the previous year (204 women and 329 children), 249 of the overall population were categorised as Irish, 42 were English, 36 American, 15 Germans, 7 Scotch, 3 Swedes, 11 French, 1 and 1 was Polish. A further 169 were categorised as, born in America of Irish parents.Footnote 87 Medical care in such facilities mainly comprised fundamental hygiene, food and shelter. The admission types reflected the behavioural patterns exhibited by immigrants who were not well versed in medico-legal matters. Similar to that of MGH, there is strong evidence of fearful and reticent users.

One hundred and forty-six who were admitted were in a diseased state, or suffering from falls or burns. In two cases the effects of cold – frost bitten- most of them drugged before entering, many entirely hopeless.Footnote 88

Desperation also characterised the mode of admission, the infants presented ‘diseased or drugged, often in the most disgusting state, and frequently half starved’.Footnote 89 The secretary of the board, Mrs John C. Peters pointed to the use of wet nurses given to alcoholism and feeding too many children as being a primary cause of marasmus (a generic term to describe physical wasting in children).

The problem with some of these philanthropically run institutions is that they were short-lived, and the extant records are also fragmented.Footnote 90 They tried, as Janet Golden has argued, to learn from past mistakes by keeping ‘the virtuous from the vicious’ but all had similar social purity ideals.Footnote 91 For example, the rationale for the foundation of the New York Infant Asylum in 1865 by the Episcopalian Reverend Richmond, was:

to reform a class of unfortunate young women whom he found in the maternity wards of Bellevue Hospital, in his visits of mercy to that institution. In many instances they were virtuous persons who had been betrayed under promise of marriage and were desirous of leading virtuous lives. As the wards of the hospital were open to the public on certain days of the week, the maternity division was visited by procuressses, who succeeded in tempting these women to enter disorderly houses as soon as they were able to leave.Footnote 92

Another aspect of the history of the foundation of such institutions was the important role played by women in resolving the problem. The records of female-run hospitals also provide a very strong impression of class differences in the American metropolis. Two types of women were instrumental in establishing maternity care for poor immigrants: the lady governors who helped with fund-raising and the upper and middle-class women who aspired to break professional barriers to becoming doctors. For example, Dr Marie E. Zakrzewska (1829–1902) helped her fellow pioneer Dr Elizabeth Blackwell to establish the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1856. According to Drachman, its origins can be traced to Blackwell’s out-patients department in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1849.Footnote 93 In 1859 Dr Zakrewska was appointed as a professor of obstetrics at the Female Medical College of Boston. She undertook the role on the condition that an appropriate clinical institution run by a board of lady governors be established to provide proper instruction for her students. As with other hospitals, the board adopted a ‘stewardship’ role with respect to poor patients.Footnote 94 Dr Zakrzewska had a very fragmented relationship with the college funder Samuel GregoryFootnote 95 and resigned from that position after 3 years, but the experience formed the genesis of the NEHWC which was founded in Boston in July 1862.Footnote 96 It was recognised that an all-female hospital was crucial to the success of this new hospital owing to what was termed ‘the affectionate trust that flows out naturally to one of their own sex’. Footnote 97 The NEHWC ethos as being ‘the only place where a woman – not a pauper, but of narrow means – can receive the comfort and care so necessary at childbirth’ provided a hospitable substitute to vernacular care in rural Ireland, which was paid in kind.Footnote 98 The lying-in hospital catered for three classes of women, the soldier’s wife, the deserted wife and the third ‘the unmarried women, are saved from moral and physical ruin, by finding here a hand extended, which is willing to lift them up and hold them in usefulness and respect’.Footnote 99 According to Vogel, single mothers accounted for 57 of the total number of 118 cases at the NEHWC in the first 18 months of the 1870s. He contends that abject poverty was a primary factor in their admission as hospitals were places that respectable people avoided.Footnote 100

The annual reports accounted for ‘a constant daily record of faithful service performed, of suffering alleviated, of evil corrected and of life saved’.Footnote 101 Although it was voted in July 1865 to charge eight dollars a week for hospital fees, and four to those of reduced means, the lying-in section and the dispensary remained a free service.Footnote 102 Ten beds received a thousand-dollar subvention from the Lying-in Corporation, whose hospital ceased operation some years previous. Apart from the fact that it was an all-female hospital, that services were free provided a powerful incentive for poor Irish women to engage with maternity services.Footnote 103 The dispensary was described as a ‘most powerful instrument of good’ to which women and children flocked on a daily basis not only for medical treatment, but also for ‘kind and thoughtful advice for the preservation of health’.Footnote 104 The founders were aware that ‘The Lying-in Department is the only place outside of the almshouse, where a homeless woman can find shelter in the sacred and momentous hour of childbirth’.Footnote 105

The MGH records do not assiduously record natality in the 1860s and, as a pre-existing institution with various strict admission criteria, it was not too immigrant friendly. By contrast, the NEHWC accepted patients who were rejected by MGH and, in keeping with wider social and evangelical movements, the work of the lady physicians was augmented by a board of lady visitors, who gave counsel to less fortunate women.Footnote 106 Further to its strong philanthropic and evangelical mission, the NEHWC’s primary function was to train female physicians and later nurses. Footnote 107 According to her biographer Arleen Tuchman, Zakrewska was anti-Catholic and was not well disposed to Irish women whom she believed ‘resort at once to beggary or are inveigled into brothels as soon as they arrive’. She was not too enamoured by the French either, whom she believed took on ‘private lovers’ to support themselves.Footnote 108 Virginia Drachman traced her strong anti-Catholic bias to ancestral reasons, as her aristocratic family was forced to flee from Russian-occupied Poland to Germany in the late eighteenth century and in the process, her grandfather made a strategic conversion from Catholicism to the Protestant faith.Footnote 109

The NEHWC operated a dispensary located in Roxbury. As Table 1 shows the Irish were as significant in number as the American-born poor. In 1864, of a total number of 2 224 patients, some 695 Irish received care at the NEHWC dispensary and hospital.Footnote 110 In 1867, the number of Irish patients treated at NEHWC was 2 208, which, for the first time surpassed the number of American born (whose figure stood at 2 122). They comprised nearly 50% of all dispensary cases (2 016 of 4 575) 66 of the 198 hospital cases and 126 of the 281 home visits.Footnote 111 In 1868, the dispensary was forced by the sheer volume of patients to bring in a charge of 25 cents for each prescription except for those who could provide sufficient proof of destitution.Footnote 112

Table 1. NEHWC admissions (surgical, medical and Lying-in)

Source: NEHWC, AR, 1868, 23; NEHWC, AR, 1869, 12; NEHWC, AR, 1871, 13; NEHWC, AR, 1872, 13. NEHWC, AR, 1873, 15; NEHWC, AR, 1874, 17; NEHWC, AR, 1875, 22.

Dr Zakrewska was concerned about financial difficulties, which was compounded by ‘her growing disillusionment with the increasingly Irish patient population’.Footnote 113 She feared that in turn the NEHWC would not provide a quality medical training for women and this, according to Tuchman revealed her ‘extreme hatred of the Catholic Church’. These staunch positions exhibit a very poor understanding of the socio-economic conditions of her patients, who were dealt with mainly by cadres of what might now be termed interns or doctors-in-residency. The NEHWC had a voluntary Board of Governors, Dr Zakrewska and attending physicians occupied the upper echelons, while the resident physicians and the nurses did the actual day-to-day work.Footnote 114 As such the attending physicians were removed from the daily grind of dealing with patients. Reverby argues that ‘common gender’ did little to resolve ‘disputes that underscored the physicians’ power’ between medical and nursing staff and cites the power structure as the primary factor.Footnote 115 The all-female staff was acutely aware of the vital services they performed especially as a refuge for young girls. Dr Susan Dimock was emphatic that despite financial constraints that this should remain a core duty of the hospital. She described some patients as ‘often not yet seventeen years of age, who have been betrayed and abandoned’, she stressed the sad realities that were they refused ‘refuge we thrust them only too surely to suicide or a life of infamy’.Footnote 116 Unfortunately, Dr Dimock died on board the Schiller which was wrecked near the Scilly Islands in April 1875.Footnote 117 Her posthumous memoirs also noted her care of patients and their appreciation of her empathy.

Ever since my connection with the hospital, a great need has been constantly under my eyes. I refer to our maternity patients during the last month of pregnancy before they enter the hospital and also when time comes for their discharge, and they are, as often, homeless and friendless. During the past year, two ladies, moved by the cases of terrible suffering which we brought to their knowledge, have done much for these deserted wives and young mothers, who though sometimes unmarried, are often still comparatively innocent. These have been saved from deeper sin and degradation, by the untiring efforts of these friends, who obtained subscriptions, paid the board of these poor women before labour and after their discharge convalescent from the hospital: and, when they became able to work found them situations where the child could be received with the mother.Footnote 118

Insightful residents made observations about the character of patients and inherent social problems. Reporting in 1868 on the 516 lying-in cases to date, it was estimated that twenty women entered hospital carrying dead children, on examination, it was found that their condition was down to deliberate and most likely criminal actions. The resident physician observed how a culmination of socio-economic factors led to the grim outcomes:

Various reasons were given by the patients for this condition such as heavy falls, blows received, over-work etc. in many instances there were indications of attempted destruction of the foetus before pregnancy had ended. Of the fifty children who died soon after birth, many had lost their lives through this criminal process, while others had not the vitality to live, as for example, the triplets born last year and several cases of twins.Footnote 119

Hallmarks of domestic violence characterised the case of Mary D. an Irish deserted wife, who was about 25 years of age when she fell prey to the charms of John M., she had one previous child and lived with Mrs Patrick F. of Roxbury. Her slow labour resulted in a dead born child whose ‘left side of face considerably ecchymosed, lips black. Brain softer than normal … left lung collapsed’.Footnote 120 Being married did not necessarily offer home comforts either, Kate R.’s husband John R.’s whereabouts was unknown at the time of her confinement in 1874.Footnote 121 This was also the case for mother of three Mary O’S, during her confinement with her fourth child.Footnote 122 For some the desire to remain anonymous governed the way in which they engaged with hospital admissions, for instance Maria G., mother of three did not give names or residential details of her next of kin.Footnote 123

In 1871, Resident Physician, Dr Buckel, wrote how several babies were taken in ‘so poisoned by patented nostrums’, one child who had been boarded-out by its mother while she worked ‘in service’ was reduced to weighing 7.5 lbs. at 3 months of age. Buckel opined the state of the unregulated patent sector: ‘Pitiful, indeed, is the fate of these babies deprived of the care of natural guardians, and subjected to the influence of these infamous nostrums’.Footnote 124 Although the NEHWC was concerned for the wellbeing of infants, it did not operate an adoption service like its counterparts in New York. With reference to the case of baby E., the child of a 16-year-old German immigrant, some letters were written to the NEHWC by the Massachusetts Infant Asylum on 22 May 1887 about putting the child up for adoption. This prompted the NEHWC to adopt an official position which was signed by Governors, ED Chiney, AH Clarke and MCE Barnard, and stated that:

The Hospital takes no responsibility in regard to the adoption of children. If the mother is determined to give up the child and the party wishes to adopt it and she consents we have no right to interfere. If the party adopting did not appear worthy we might advise her but no more.Footnote 125

NEHWC sample

According to the Dillingham Commission criteria, ‘A woman was classified as Irish if both of her parents were born in Ireland, as Italian if both parents were born in Italy, as American if both parents were born in the United States’.Footnote 126 Here, I adopted the criteria of Irish-born to construct a sample of 553 patients from the NEHWC admissions registers from 1872 to 1900. Of this number, 180 were of women who were not married to the father of the child. Their reception was contrary to the ethos of the hospital, which in the main tried to look after more ‘respectable’ types, but had a third criteria for unfortunate women needing refuge. The records of CWA are fragmented, owing to the fact that some of the earlier lying-in hospitals were short lived so I have not used them here. In what follows, I provide an overview of what can be gleaned from NEHWC records in prosopographical terms from admissions records.

The Boston Lying-in Hospital was closed from 1853 to 1872 and, from 1862 to 1873, the NEWCH was the only recourse for the poor, and charity was received if a woman met basic moral criteria. As Drachman has argued worthiness for being a patient was determined ‘by her marital status, piety or appearance’.Footnote 127 Reverby contends from her study of the Boston Lying-In Hospital, that poor and ‘working class women continuously circumvented the rule that allowed a woman only one illegitimate birth in the hospital by changing their names upon return visits’.Footnote 128 Marriage and death certificates (or equivalent forms of evidence) were important components of the admission process, as were letters of good standing from employers willing to attest to high moral character. This was the case for several Irish patients whose respectability was vicariously achieved through the nomination of married women on their forms. For instance, domestic Mary C. gave the name of a friend Mrs R. (implied respectability) in lieu of her parents.Footnote 129 Likewise Delia C. gave account of herself through her friend Mrs F. who lived at 2 Benton St, she nominated her mother Ellen F., the father of the child was William T.Footnote 130 Delia C. may have been married at some point, but it is also possible that she gave her mother’s maiden name. Single women like Mary M. often nominated sisters, in her case, Nora as their next of kin. Even in these sparsely detailed forms other socio-economic snippets can be gleaned, Nora was likely in service as two addresses were supplied.Footnote 131 The same was true of Bridget C. whose sister Maggie’s address was care of a big house.Footnote 132 Twenty-year-old Jennie L. provided full details of her parents address in Ballinasloe, County Galway, Ireland and that of a friend Mrs Mary S. who lived in the Greater Boston area.Footnote 133 Mother of two Ellen B’s husband John or Patrick was in jail, this vague reference may have been linked to his own alias usage or perhaps her own inconsistent efforts to feign marital respectability.Footnote 134 Nineteen-year-old Mary M.’s friend Mrs Mary F.W. of Townsend St was nominated on her form in lieu of her parents.Footnote 135

The protection of employers was apparent to the medical authorities who logged Nellie D.’s employer Mrs F. and her Dorchester address instead of that of her husband or her parents. In fact, there is every possibility that the record of her marriage was falsified to give a veneer of respectability.Footnote 136 Abandoned wife Bessie O’ B. had no previous children, her parents were deceased in Ireland and her husband Richard had ‘departed for parts unknown’, she gave no address.Footnote 137 Mary C. nominated her cousin William as the father of her child.Footnote 138 Not everyone had the comfort of friends willing to be named, Bridget M.’s unnamed friend lived on Sewall St.Footnote 139 The prospect of childbirth prompted Annie McG. to give the full name and address of her husband and father of the child, the address of her parents in County Longford and that of her friend Mrs Patrick McK. on 60 Lowell St.Footnote 140 Unmarried Nora D. had conceived in Ireland; it was noted in November 1890 that she had only been in the country 7 months. She had the comfort of her sister Bridget who lived ‘in America’.Footnote 141

Sarah K.’s case was particularly poignant, her husband, Timothy, died 7 months before their third child was born. She proudly claimed her Cork ancestry and even provided the name of the townland together with her parents’ full names. She had a 9-lb baby girl, and both mother and child were discharged ‘well’ on 24 December 1872 after a 20-day stay.Footnote 142 A similar case was that of Mary Ann C., whose husband Henry died 5 months before she gave birth to a baby girl.Footnote 143 Anne H. was a deserted wife who gave birth to a baby boy in December 1872.Footnote 144 Women were careful about what they divulged about the paternity of their pregnancy but a few were wonderfully frank, like Mary K. who had eight children and proffered two names, that of her husband Lahan K. and that of another likely candidate William W.Footnote 145 Unmarried Ellen B. admitted to having had a previous miscarriage and named James C. as the father of her child. Clearly her concerns for her own safety and that of her unborn child trumped that of moral probity. This was made somewhat easier by the fact that her parents were resident in Ireland.Footnote 146

The complexity of the immigrant family’s economic circumstances can also be ascertained from the records. Houseworker, Mrs Bridget H.’s husband worked at Monument Beach in Cape Cod, but his friend Michael W. of Jamaica Plain stood in as a nominee for the purposes of the NEHWC form.Footnote 147 Ms Norah O’G. asserted her individuality using her maiden name despite being married to John B., it was noted as a curiosity in the admission form.Footnote 148 Similarly, the father of Rose C.’s child, John W., was recorded as being ‘coloured’.Footnote 149 Annie T. nominated her sister-in-law as well as her husband as next of kin, they all lived at 104, 3rd Street South Boston.Footnote 150 Political consciousness also found expression in the records with Annie S. recorded as being from the North of Ireland. This was some 40 years prior to the Government of Ireland Act (1920) that began the process of partition but with a majority Protestant population in the province of Ulster her actions may have been a concerted effort to put clear water between her and her Roman Catholic compatriots from the other three Irish provinces.Footnote 151 Extended kinship bonds were expressed in the records too, Annie M. lived with her husband and sister at No. 9 Smith Street Place.Footnote 152 Minnie K. who was a servant born in County Down, was married to Robert, and lived at her employers’ residence on Pleasant St Brookline. She was part of a family migration unit, as her parents James and Eliza B. lived at Shepard St. in Brighton.Footnote 153 The support of her mother proved invaluable to Elizabeth B. as she lived with her on 1473 Tremont St, there was no mention of the whereabouts of her husband on the form.Footnote 154 The same stood true for abandoned primipara Annie McD., whose parents appeared to be her sole support.Footnote 155 Lizzie S. and her husband George occupied the residence of his/her brother Michael S. on 155 Burrington Rd.Footnote 156 Forty-year-old Mary C. had eight children and noted how all of her previous labours were ‘all very hard’, she had suffered one miscarriage, she earned her living by washing and her husband Daniel, who lived at 51 Vale St. was recorded as not having any occupation.Footnote 157

Several women opted to keep personal information like age and the identity of the baby’s father to themselves, this suggests that women were unfamiliar with or fearful of the reach of medico-legal power. Age was a very poorly understood concept and there is plenty of evidence to suggest age heaping (rounding up or down to the nearest 5 or 0) and there are many whose age was unknown or not given. For instance, Bridget McN., born ‘about 1851’ whose parents lived in Ireland entered NEHWC in November 1873 to deliver her baby. She was unmarried and gave her parents’ full address in Ballyshannon, County Donegal.Footnote 158 Efforts to find her in Irish civil records have proven fruitless, which is unsurprising given her birth year predated birth registration by some 13 years. Birthdates after the 1863 Act do not correspond neatly either, for instance that of Jennie L., born in 1865 in Ballinasloe did not link her to a vital registration record or family resident there.Footnote 159 Those who present in the American metropolitan setting were acutely aware of being recorded, we have no idea what degree of literacy these patients had but many would have come from the oral tradition. Several adopt memorable birth dates like 17 March and 24 December: St Patrick’s Day and Christmas Eve, respectively, both were important dates in popular religious devotions.

What is also apparent in the NEHWC records is the degree to which the Irish attending the lying-in gentrified as the decades progressed. For instance, the numbers identifying as domestics and conducting various other forms of housework (281 of 553) from 1872 to 1900 were replaced with women who were more numerously described as housewives (151), indicating their husbands’ economic stability. Although some of the earlier ‘housewife’ occupations may relate to domestic work for others, the addresses in later entries are more clearly defined as work in their own households. Simultaneous to this more stable lot of married women was a more favourable visual representation of Irish women in popular media and a move away from the sharp features of Harper’s Weekly pug-nosed and low-browed.Footnote 160 In the construct of this racial reengineering, she was bestowed with corresponding high moral standards.Footnote 161 By the close of the nineteenth century, nativist ire in North America was being directed towards Chinese immigrants (more specifically through the exclusion acts from 1882 to 1924) and other groups from southern and eastern Europe became more numerous in terms of arrivals than the Irish in the early twentieth century.Footnote 162

Conclusion

This article aimed to show how Irish immigrants presented as a problematic cohort for public health and how they navigated healthcare services in New York and Boston. Irishwomen coming from the mixed-medical economies of rural areas had limited medico-legal knowledge, I contend that this arose from their poor levels of engagement with civil registration of life events and healthcare structures prior to departure. In turn, they were ill-equipped for life in urban settings where public health authorities and instruments like the decennial census from 1860 and the Dillingham Commission 1907–11 singled them out as exhibiting problematic behaviours. In response to the immigrant problem a proliferation of voluntary lying-in hospitals was founded in Manhattan, some were short lived owing to funding deficits and their inability to attract fee-paying patients partly because of the negative associations with prisons, almshouses and particular immigrant groups. Two types of Irish patients emerged, those who were reticent and refused care until they were in dire straits or those who viewed the medical setting as a form of social welfare relief. While they may have instigated much of the moral panic surrounding immigrant fertility and nativist concerns about being ‘outbred’, Irishwomen eventually adapted to their new urban environs, and they learned to negotiate the medico-legal landscape with greater dexterity.

As this article has shown medical records offer several avenues for research for professional historians and genealogists, in socio-economic, cultural and health histories alike. The ‘creep’ of recent data protection legislation has and is continuing to hamper the ways in which historians of medicalisation and migration can develop new methodologies, add to, or indeed challenge existing scholarship that has to date focussed on aggregate returns rather than individual level returns. As my brief discussion of MGH and CWA records exemplifies, the loss of texture that occurs through anonymisation and codification renders the historicity of life course histories of poor and marginalised people next to impossible. Meaningful linkage between immigration records or civil registration data cannot be made to a de-identified patient record, as it would reveal their identity. By juxtaposing the HIPAA-subjected or ‘covered’ historical data with the open records of the NEHWC this article shows the limitations to the prosopographical approach when dealing with poor immigrants. Further to this, the old problems of conducting medical history from below persist, we are at the mercy of what patients chose to reveal and what the medical personnel elected to record. It is difficult to elicit historical facts from the records, but that should not deter historians from conducting more detailed investigations. Apart from loose truths in the American records, limitations exist also on the Irish side, for instance, civil or vital registration for Roman Catholics only became mandatory in Ireland in 1864. Irish immigrants were new to surveillance systems and often their own identities were articulated and vicariously achieved through that of employers or friends willing to lend or unwittingly lending respectability. Nineteenth-century migrants were not subject to visa, or passport requirements, without formal identification requirements the data given in the medical encounter must be approached with caution. Engagement with medicalisation in the migratory context and its study not only enriches our understanding of acculturation, but also offers opportunities to add to discourses on upward mobility and its impact on the social determinants of health. It brings us back to Lawrence’s important interventions on HIPAA and the necessity to redefine what should and should not be covered entities. Quite apart from what hospital records can offer in terms of genealogical verification touchpoints, documented and undocumented immigrant health outcomes came into sharp relief during the recent global pandemic. There is much we can learn from past experiences.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken while I was Flaherty Visiting Fellow, Research Center for Urban Cultural History, University of Massachusetts, Boston (2013) and Foundation for Women in Medicine Fellow, Center for the History of Medicine, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2014). This work benefitted from conversations with Patricia Flaherty and colleagues at the CHM, Harvard, Professor Scott Podolsky, Jack Eckert, Jessica Murphy, Carolyn Hayes and the late Kathryn Hammond Baker. I would also like to thank Elizabeth Shepard, Associate Archivist, Cornell Weill Archives.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.