INTRODUCTION

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is broadly seen as the responsibility of organisations for enhancing their positive, and reducing their negative, impacts on society (Amaeshi, Adegbite, & Rajwani, Reference Amaeshi, Adegbite and Rajwani2016; Campbell, Reference Campbell2007). These impacts can be on different stakeholder groups – i.e., those who can affect and or are affected by the actions of a business (Freeman, Reference Freeman1994). Stakeholders include local communities, consumers, employees, natural environment, shareholders, governments, etc. (Vlachos, Panagopoulos, & Rapp, Reference Vlachos, Panagopoulos and Rapp2014; Werther & Chandler, Reference Werther and Chandler2006). In other words, CSR can be succinctly described as corporate behaviors with net positive impacts on stakeholders (Turker, Reference Turker2009). Framed as such, CSR goes beyond compliance with the law to encompass efforts at improving the welfare of the society. It becomes an approach and an orientation to how business is done – i.e., an organizational culture of a sort (Duarte, Reference Duarte2010).

CSR has recently become a burgeoning interdisciplinary field, albeit with a significant focus on firm level activities. This firm-centric approach has led scholars to explore, for example, the relationship between CSR and firm reputation (e.g., Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, Reference Aguilera, Rupp, Williams and Ganapathi2007; Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Walsh, Bartikowski, & Beatty, Reference Walsh, Bartikowski and Beatty2014), customer preferences (e.g., Fagerstrøm, Stratton, & Foxall, Reference Fagerstrøm, Stratton and Foxall2015; Schuler & Cording, Reference Schuler and Cording2006; Sen & Bhattacharya, Reference Sen and Bhattacharya2001), and corporate financial performance (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2012; Peloza & Shang, Reference Peloza and Shang2011), amongst others. Although the central purpose of most of these studies is to understand the instrumental and financial benefits of CSR, which are largely externally-driven, the focus has gradually turned to internal drivers of CSR, such as organizational structures and processes (Aldama, Amar, & Trostianki, Reference Aldama, Amar and Trostianki2009; Galbreath, Reference Galbreath2010), organizational leaders (Groves & LaRocca, Reference Groves and LaRocca2011), and employees (Lin, Reference Lin2017; Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015; Santhosh & Baral, Reference Santhosh and Baral2015). As such, there is a growing interest to extend CSR to human resources management (HRM) and employee issues, which is evident in the gradual emergence of responsible HRM as a sub-field (Alcaraz et al., Reference Alcaraz, Susaeta, Suarez, Colón, Gutiérrez-Martínez, Cunha and Pin2017; Shen & Benson, Reference Shen and Benson2016; Shen & Zhu, Reference Shen and Zhu2011).

The extension of CSR to HRM has led scholars to advocate and adopt a micro organizational behavior perspective (Jones, Willness, & Glavas, Reference Jones, Willness and Glavas2017; Morgeson, Aguinis, Waldman, & Siegel, Reference Morgeson, Aguinis, Waldman and Siegel2013; Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015) to explore the implications of CSR for such issues as talent attraction (Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2011; Turban & Greening, Reference Turban and Greening1997), job satisfaction (Edmans, Reference Edmans2012), organizational commitment (Glavas & Kelley, Reference Glavas and Kelley2014), and employee performance (Gao & Yang, Reference Gao and Yang2016), amongst others. Other researchers have also focussed on how employees perceive their organizations’ engagement in CSR and how this perception shapes their behaviors (Glavas & Godwin, Reference Glavas and Godwin2013; Vlachos et al., Reference Vlachos, Panagopoulos and Rapp2014). Most of these previous studies that took the micro-organizational perspective on CSR reported strong positive relationships between CSR and employees’ positive behaviors. However, few studies, (e.g., Ormiston & Wong, Reference Ormiston and Wong2013) linked an organization's CSR engagement with subsequent unethical behaviors of top management (Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015). These contradictory findings suggest that the debate on the impact of CSR on employees’ work behaviors is still raging and inconclusive. Despite what has been achieved so far, studies on the mechanisms that account for the relationships between CSR and employee job behaviors, especially extra-role behavior (Jones, Reference Jones2010), have also not been adequately addressed. A similar observation has been made by Glavas (Reference Glavas2016) who acknowledged that, although CSR affects employees, we still do not know much in relation to the reasons behind such influences, as well as how and when they occur.

One of the prevalent ideas in the literature on how CSR impacts on positive organizational behavior is that employees create their own meanings from their organizations’ engagement in CSR (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017), and CSR increases employees’ perceptions of respect and identification with their organizations (Farooq, Rupp, & Farooq, Reference Farooq, Rupp and Farooq2017; Helm, Reference Helm2013; Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim, Reference Kim, Lee, Lee and Kim2010). These findings, in turn, have implications for employees’ formation of positive work attitudes (Gond, El Akremi, Swaen, & Babu, Reference Gond, El Akremi, Swaen and Babu2017). Following this line of thinking, we propose that organizational members, also, learn to become good organizational citizens through their organization's engagement in CSR activities.

Extant learning literature provides abundant evidence that people tend to learn more from observation than just being told what to do. Studies on social learning, observation learning, and imitation (Bandura, Reference Bandura and Goslin1969; Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer, & Welch, Reference Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch1998; Byrne & Russon, Reference Byrne and Russon1998) provide clear understanding of how people learn from the actions of others, and how this learning shapes their subsequent behaviors in line with what they have acquired through observation or imitation. In other words, it could be postulated that organizational members could learn to become better corporate citizens through their perceptions of their organization's CSR activities. This postulation, also, resonates well with the social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). For example, Rupp and Mallory (Reference Rupp and Mallory2015) argue that when leaders of organizations enact and perform CSR, it creates opportunities for norms regarding respect for others to be crystalized and propagated in the organization. Thus, through observing others, especially leaders, organizational members learn and reproduce behaviors that are based on principles of CSR (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Fortis, Maon, Frooman, & Reiner, Reference Fortis, Maon, Frooman and Reiner2018). Leaders’ engagement or emphasis on CSR helps employees to evaluate how the organization values others (Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015). Arguably, this situation is likely to foster a learning culture that supports engagement in behavior that places priority on the need to value others (Thornton & Rupp, Reference Thornton and Rupp2016).

Organizations with strong learning culture are also good at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and also tend to modify behaviors of their employees to be in line with the acquired knowledge and insight (Garvin, Reference Garvin1993; Joo & Lim, Reference Joo and Lim2009). According to Joo and Lim (Reference Joo and Lim2009), these organizations use their learning culture to effect behavioral and cognitive changes among organizational members ‘in order to convert words into action’ (49). As such, in organizations where a learning culture is emphasized, new learning is systematically sought and embedded in a way that is sustained and disseminated to employees (Marsick & Watkins, Reference Marsick and Watkins2003). In that regard, it is argued that organizations that participate in CSR activities tend to foster learning cultures that support commitment to such activities (Carter & Jennings, Reference Carter and Jennings2004) and adopt corporate values that emphasize duty-based morality and a commitment to helping others (Jones, Felps, & Bigley, Reference Jones, Felps and Bigley2007; Maon, Lindergreen, & Swaen, Reference Maon, Lindgreen and Swaen2010). Such learning cultures enhance organizational members’ sensitivity to the environment and society and could help employees to become more proactive; including going the extra mile to support their colleagues and their organizations (Islam, Khan, & Bukhari, Reference Islam, Khan and Bukhari2016). Taken together, these suggest that organizational learning culture could be a potential mediator of the relationship between CSR and OCB.

OCB consists of informal job-related behaviors that organizational members can indulge in to make or withhold work activities without regard to sanctions or formal incentives. Many of these contributions, aggregated over time and persons, have been found to enhance organizational effectiveness (Organ & Konovsky, Reference Organ and Konovsky1989; Rapp, Bachrach, & Rapp, Reference Rapp, Bachrach and Rapp2013; Turnipseed & Rassuli, Reference Turnipseed and Rassuli2005). We reason that firms that engage in CSR would also have employees who would be very willing to engage in more prosocial behaviors such as OCB, that benefits the organizations. Although few studies confirm that CSR leads to employee engagement in OCB (e.g., Evans, Goodman, & Davis, Reference Evans, Goodman and Davis2011; Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen, & Chiu, Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010), the mechanisms by which CSR leads to OCB has not been adequately examined. For instance, Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010) recognized that good examples of corporate citizenship by the organization can lead to employee citizenship behavior towards the organization. However, they only investigated the direct relationship between perceived CSR and OCB. Since most researchers agree that CSR impacts positively on employee, it would be reasonable to understand how CSR influences employees’ positive behaviors towards their organizations. Thus, our focus is on how CSR shapes the learning culture of an organization towards being sensitive to the environment and how this can lead to employee OCB.

Thus, in addition to examining the link between employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ engagement in CSR and their personal engagement in OCB, it is also important to understand the mechanisms that underpin such relationship. As far as we can see, it appears no study has directly examined the mediating role of organizational learning culture in the relationship between CSR and OCB despite calls by researchers for more empirical studies in this area (e.g., Gao & Yang, Reference Gao and Yang2016). We, therefore, extend previous knowledge on how CSR impacts organizational positive behaviors by examining organizational learning culture as a possible mechanism that helps to translate employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ CSR activities to their engagement in positive work behaviors. In order to strengthen the robustness of our findings, we examined this relationship in Nigeria – a work environment with unique characteristics different from the stylised CSR enabling institutional contexts of developed economies (Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adegbite and Rajwani2016; Campbell, Reference Campbell2007; Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008), where organizational behavior has received much empirical attention.

The Nigerian Context

To study corporate citizenship in Nigeria is pragmatic for many reasons (Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie, & Amao, Reference Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie and Amao2006). Nigeria is the most populous black nation in the world and a key player in the global oil business. Amaeshi and colleagues (Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie and Amao2006; Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adegbite and Rajwani2016) assert that despite Nigeria's real and potential wealth, the country still ranks very low in virtually all development indices. The country's economy is still emerging but contemporaneously shrouded with tough socio-economic and infrastructural challenges including poverty (Khara, Hamel, & Hofer, Reference Khara, Hamel and Hofer2018). In addition to the poverty level, Nigeria ranks low (148 out of 180) on the 2017 Transparency International Corruption Index and World Bank Governance Index, and the legal institution is not robust enough to curtail corporate social irresponsibility (Windsor, Reference Windsor2013). Despite these contextual differences from most developed economies, Nigerian society claims to be deeply religious and exhibits high levels of collectivist values and solidarity and low levels of individualism (Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie and Amao2006, Waldman, Siegel, & Javidan, Reference Waldman, Siegel and Javidan2006). Consequently, companies operating in Nigeria are expected by the society to be good neighbors through responsible business practices.

The difference in context and the presence of strong collectivist values make Nigeria an interesting empirical site for the study of CSR. Although there have been a number of studies on CSR in Nigeria, most of them tend to focus on multi-national firms. The few that focused on indigenous firms either concentrated on the perception and practice of CSR or on its relationship with financial performance of firms (e.g., Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie and Amao2006; Uadiale & Fagbemi, Reference Uadiale and Fagbemi2012). Surprisingly, there seems to be no study on how employees’ perceptions of the CSR activities of their firms influence their attitudes towards their organizations in Nigeria, despite the rich collectivist values prevalent in the country. This profound omission is further puzzling given how well established it is in the literature that employers’ behavior may spillover to employees that may in turn behave positively towards their organizations.

The choice of Nigeria for this study is also important in relation to understanding OCB in cultures outside North America and Europe, where most of the studies on OCB have been conducted. A common limitation of prior research on OCB is the assumptions of most researchers that OCBs are widely applicable across cultures. OCB, as a construct, was conceived within the North American organizational behavior contexts, and most of the studies on OCB were done with settings, participants, and measures suited to that culture (Organ & Paine, Reference Organ, Paine, Cooper and Robertson1999). Although there appears to be consensus that OCB does have meaning and relevance in different cultures, the types of behavior that define OCB, its antecedents and consequences may differ based on context (Coyne & Ong, Reference Coyne and Ong2007; Farh, Podsakoff, & Organ, Reference Fahr, Podsakoff and Organ1990). In Nigeria, for example, Munene (Reference Munene1995) investigated correlates of OCB and found that job involvement and affective commitment were more related to OCB than job satisfaction in Nigeria. These results are slightly different from results in other countries in the United States, Europe, and Asia, which showed that job satisfaction is a strong correlate of OCB (LePine, Erez, & Johnson, Reference LePine, Erez and Johnson2002). Again, in a country where employees take less proactive measures to positively influence work outcomes (Onyishi & Ogbodo, Reference Onyishi and Ogbodo2012), engagement in CSR activities by an organization could influence employee positive perception of the organization. Such perception in turn can help employees to develop a positive attitude toward the organization including engagement in OCB. Thus, extending our understanding of the relationship between CSR and OCB as reported in other cultures (e.g., Evans et al., Reference Evans, Goodman and Davis2011; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010) to developing countries of Africa is worthwhile. This underscores the notion that more research on the relationship between organizations’ practice of CSR and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior is needed.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The relationship between employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ engagement in CSR and their behaviors and attitudes can be appreciated from the social cognitive theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura1989; Wood & Bandura, Reference Wood and Bandura1989). The social cognitive theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986) recognizes the interacting influences of and reciprocal relationship that exist among personal and cognitive factors, environmental factors, and behaviors. The cognitive, behavioral, and environmental determinants operate as interlocking and continuous mechanisms that affect one another bidirectionally (Davis & Luthans, Reference Davis and Luthans1980; Lent, Brown, & Hackett, Reference Lent, Brown and Hackett1994; Wood & Bandura, Reference Wood and Bandura1989).

From the social cognitive theory perspective, employees would tend to exhibit OCB based on their positive perceptions of the involvement of their organizations in CSR. According to Wood and Bandura (Reference Wood and Bandura1989), there are four component processes that drive observational learning that are possibly implicated in employee positive work attitude, as a result of their organizations’ engagement in CSR activities. These include attentional, cognitive representational, behavioral production, and motivational processes. Engagement in CSR activities attracts the attention of stakeholders, including employees, and this creates positive impressions that lead to transformation of these cues to peoples’ consciousness. The cognitive processes are therefore necessary for the motivation to develop behavioral responses that are in congruent with what they have observed. In other words, individuals have cognitive schemas that help them categorize organizations (Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher1991).

The social cognitive theory (SCT) emphasizes that when people see a (role) model performing a specific behavior, based on their observation, the information becomes useful in guiding subsequent behaviors. By simply watching a (role) model, it also prompts the observer to engage in a behavior they have learned in the past. Human beings learn by internalizing information in their memories and during the time of need to respond to a similar situation they simply recall that information. It is well established that cognitive and behavioral factors are related (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986; Levine, Resnick, & Higgins, Reference Levine, Resnick and Higgins1993), and both are essentially influenced by social context (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Resnick and Higgins1993). More so, SCT may be viewed as a coherent and extensive set of theories that effectively explains and predicts human motivation and behavior (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). McCormick, Alavi, Babak, and Hanham (Reference McCormick, Alavi, Hanham and Ortenblad2015) assert that the overarching, meta-theory in SCT is Triadic Reciprocal Determinism, which proposes that behavior, internal personal factors, and the external environment are reciprocally related, and these relationships explain human functioning (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). With regards to CSR, individuals tend to observe value-driven behaviors being taken by leaders or the firm and tend to match these behaviors with the schema or prototypes they have in their minds (Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015). Based on these matching, they are able to categorize the firm's or leader's behaviors in terms of level of social responsibility. Gond et al. (Reference Gond, El Akremi, Swaen and Babu2017) noted that the individual evaluation of CSR initiative is an important factor in employee reaction to CSR. The perception shapes the behavior of employees toward the organization and impact on work efforts of employees (De Luque, Washburn, Waldman, & House, Reference De Luque, Washburn, Waldman and House2008).

Organizational members would view the involvement of their organization in CSR as extra and positive efforts of the organization to impact society. This perception is likely to help these employees learn and develop positive views about engagement in extra-role efforts. Aguinis and Glavas (Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017) argue that employees tend to make sense of an organization's CSR activities and that through positive perception of CSR, employees find meaning through work. According to Aguinis and Glavas (Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017), this happens because CSR expands the scope of work to incorporate making a broader impact on society, and through sense making, employees acquire new experiences at work that also expand their scope about their job impact. As social cognitive theorists argue, people are most likely to engage in similar behaviors they have learned if such behaviors produce valued outcomes, rather than punishing effects or negative outcomes (Wood & Bandura, Reference Wood and Bandura1989). It is also argued that people are motivated by the success of other people but are discouraged from engaging in behaviors that are known to lead to adverse effects or consequences. An organization's CSR activity is seen as a successful attempt of an organization to engage in extra-role effort that impact positively on society. Employees are therefore more likely to learn from such activities and would in turn engage in behaviors that go beyond their duties, which would portray them also as better citizens. In other words, they are likely to engage in OCB.

OCB has been defined as employee behavior that goes beyond the call of duty, that is discretionary and not explicitly recognized by the employing organization's formal compensation system but are relevant for the overall functioning of the organization (Organ, Reference Organ1988; Organ & Konovsky, Reference Organ and Konovsky1989; Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Bachrach and Rapp2013; Smith, Organ, & Near, Reference Smith, Organ and Near1983; Turnipseed & Rassuli, Reference Turnipseed and Rassuli2005). OCB was first conceptualized to include two major dimensions: behaviors that are directed at specific individuals or groups within the organization, and those directed at the organization (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Organ and Near1983). Organ (Reference Organ1988) further proposed three additional dimensions: courtesy (trying to prevent work-related interpersonal problems); sportsmanship (willingness to tolerate minor frustration in the job); and civic virtue (involving oneself in and being concerned about the group and the organization). Subsequent researchers have identified other forms of OCB. For instance, Van Dyne, Grahams, and Dienesch (Reference Van Dyne, Graham and Dienesch1994) identified three citizenship dimensions – loyalty OCB, participation OCB, and service delivery OCB. Based on the construct conflict and over-lap, OCB over the years has been mainly defined along the two major dimensions – organizational citizenship behavior directed to specific individuals in the organization (OCBI), and this includes altruism and courtesy; and organizational citizenship behavior directed to the organization (OCBO), which includes generalized compliance, sportsmanship, and civic virtue (Niehoff & Moorman, Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993; Organ, Reference Organ1988; Rioux & Penner, Reference Rioux and Penner2001; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Organ and Near1983). There appears to be consensus on the positive impact of OCB on organizational effectiveness (Podsakoff, Ahearne, & Mackenzie, Reference Podsakoff, Ahearne and Mackenzie1997; Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, & Blume, Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009). OCB can be distinguished from other forms of organizational behavior because it is discretionary. This means that the behavior in question is not an enforceable requirement of the role or part of the job description but rather a matter of personal choice. Engagement in such behaviors are not ordinarily rewarded and its omission is not also understood as punishable. CSR is also a form of discretional activities of organizations. It is therefore reasonable to propose that employee positive perception of their organization's engagement in CSR will be related to their OCBs.

Scholars have recognized the importance of employees’ perception of an organization's CSR on organizational performance (e.g., Gao & Yang, Reference Gao and Yang2016; Helm, Reference Helm2013; Jones, Reference Jones2010). For instance, Rodrigo and Arenas (Reference Rodrigo and Arenas2008) demonstrated in their study that when employees see their organizations get involved in CSR, it makes them feel that their contributions in the organization have a degree of importance that transcends economic aspects and that their work may contribute to a better society. Hillenbrand, Money, and Ghobadian (Reference Hillenbrand, Money and Ghobadian2013) showed that CSR, which they conceptualized to encompass a comprehensive analysis of business responsibilities of an organization, was a significant factor in ensuring positive attitudes of both customers and employees toward an organization through positive beliefs and trust on the organization. Empirical studies that examine the link between CSR and extra-role efforts in organizations are beginning to emerge (Jones, Reference Jones2010). In a recent study, Thornton and Rupp (Reference Thornton and Rupp2016) investigated the effects of justice climate and CSR on employee prosocial behaviors. The results of their study confirmed a significant relationship between justice climate and employee prosocial behavior and a significant relationship between CSR and employee volunteering behaviors. Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010) also found that the three aspects of CSR (legal, ethical, and discretionary corporate citizenship) investigated in their study were related to OCB. We thus hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Employee perceptions of organizational CSR will be positively related to employee OCB.

CSR and Organizational Learning Culture

CSR can influence the learning culture of an organization and its sensitivity to societal welfare. When operationalizing learning culture, Watkins and Marsick (Reference Watkins and Marsick1997) recognized an aspect that deals with connection of the organization to the environment. This dimension describes how people are helped by their leaders to see the effect of their work on the entire organization and how employees can scan the environment and use information obtained to adjust work practices (Marsick & Watkins, Reference Marsick and Watkins2003). This component of organizational learning culture is therefore important in explaining how perception of CSR is linked to employee engagement in OCB. Culture of an organization is built by leaders and other key people who learn through experiences and are able to influence others, thereby creating an environment that shapes overall expectations in the organization (Marsick & Watkins, Reference Marsick and Watkins2003). Organizations that are actively involved in CSR will therefore build learning cultures that reflect the principles of CSR. For instance, Carter and Jennings (Reference Carter and Jennings2004) found that organizations involved in CSR tend to have cultures that are fair, supportive, and place priority on welfare of others. Consistent with this view, Galbreath (Reference Galbreath2010) demonstrated that formal strategic planning and cultural factor (which he referred to as humanistic culture), had positive effects on CSR. Humanistic organizational culture is described as one that places emphasis on team spirit, a caring atmosphere, concern for its members and welfare of other stakeholders. It was found that organizational humanistic culture influenced a firm's orientation towards treating stakeholders responsibly and this relationship was confirmed even after accounting for what could be attributed to formal strategic planning.

Organizations that engage in CSR help employees learn how to become good citizens through their philanthropic activities (Carter & Jennings, Reference Carter and Jennings2004). From the social cognitive theory perspective, behaviors of members of the organizations are shaped by both the employees’ cognitive processes and environmental factors in the organization. Organizational emphasis in CSR activities is therefore likely to shape the organizational learning environment to reflect care for the environment and emphasis on universal justice. Aguinis and Galavas (Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017) posit that members of an organization tend to make sense out of the organization's CSR initiatives especially in relation to an organization's focus on the ‘common good’ that extends beyond business interests and the sensemaking processes enable them develop sense of meaning at work. It is therefore expected that leaders and other members of organizations that engage in CSR would also develop the attitude to care for the common good of all and would make them to go beyond their job roles to exhibit behaviors that support their colleagues and the organization. This point to the fact that CSR could lead to the development of learning culture that are tied to principles and values of CSR. For instance, in a study of several Dutch companies, Cramer (Reference Cramer2005) found that an organizations’ activities in CSR impacts learning at an individual and group level. In the study, she showed that as CSR becomes an integral part of an organizations’ business culture, learning experiences of organizations in relation to CSR are transferred to individual employees and groups in the organization. These findings suggest that CSR affects organizational learning culture that supports care for the society. Thus, we predict that:

Hypothesis 2: Employee perceptions of organizational CSR will be positively related to their organizational learning culture.

Organizational Learning as a Mediator in the Relation between CSR and OCB

There are increasing concerns on the inability of previous research to establish how learning as a management strategy enables an organization to improve its performance and most of the existing literature on the area have remained descriptive and conceptual (Bates & Khasawneh, Reference Bates and Khasawneh2005; Gond et al., Reference Gond, El Akremi, Swaen and Babu2017). In one of such few attempts to provide this missing explanation, Bates and Khasawneh (Reference Bates and Khasawneh2005) demonstrated that organizational learning culture accounted for a significant variance in learning transfer climate and subsequently led to organizational innovation. This then demonstrates that organizational members could transfer what they learnt within the organization to impact on their job activities if there is existing culture that supports such transfer of learning. It has been recognized that people tend to pay attention to and learn from the behaviors of others through vicarious experiences (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). For instance, organizations that emphasize justice and care for the general good of all are more likely to have members who are sensitive to justice and care for others. It is through learning that organizations develop and sustain employee behaviors that sustain their core values. Researchers such as Grant (Reference Grant1996) have recognized the importance of organizational learning in organizational performance. For instance, Bates and Khasawneh (Reference Bates and Khasawneh2005) found that learning culture influences organizational innovation. Organizational learning has also been linked with positive employee job attitudes. In one such study, Chiva and Alegre (Reference Chiva and Alegre2009) found a strong positive relationship between organizational learning capability and employee job satisfaction. All the components of organizational learning capacity (experimentation, risk taking, dialogue, participative decision making, and interaction with the external environment) investigated in their study were found to be positively related to job satisfaction.

Since CSR is primarily viewed as a voluntary action of organizations targeted at improving society (e.g., El Akremi, Gond, Swaen, De Roeck, & Igalens, Reference El Akremi, Gond, Swaen, De Roeck and Igalens2018), employees tend to value and respect such organizations. This is because employees make sense of CSR activities and this perception enables them to develop a positive attitude towards such firms (Aguinis & Galavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017; Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008). It is expected that the sensemaking process would motivate employees to behave in a socially-responsible manner by engaging in voluntary activities that support the organization. This would be more possible in an organizational atmosphere that supports learning. If employee perception of their organizations’ engagement in CSR shapes their attitude including identification and satisfaction (Gao & Yang, Reference Gao and Yang2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee, Lee and Kim2010; Rodrigo & Arenas, Reference Rodrigo and Arenas2008), it is also likely that they would learn such proactive behaviors from their organizations through the process of socialization as explained by the social cognitive theorists. Through such learning, employees tend to mimic their organizations and become more willing to engage in OCB. Empirical studies have provided proof that organizational learning is related to several positive job attitudes or behaviors such as employee intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, goal orientation, and commitment (Joo & Lim, Reference Joo and Lim2009; Joo & Park, Reference Joo and Park2010). Somech and Drach-Zahavy (Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2004) demonstrated that organizational learning, including learning structures and values, leads to performance of OCB. In one of the few studies that attempted to link organizational learning culture and OCB, Islam et al. (Reference Islam, Khan and Bukhari2016) found that organizational learning culture is a significant factor in performance of OCB. In the same line of thought, we reasoned here that organizational members could learn how to become better organizational citizens through their organizations’ CSR activities.

In fact, an earlier study has shown that learning mediates the relationship between CSR and productivity (Carter, Reference Carter2005). In the study, Carter attempted to link Purchasing Social Responsibility (PSR), an aspect of CSR, to supplier performance. The results of the study demonstrated that PSR was related to supplier performance and this relationship was mediated by organizational learning. This provides strong argument for us to propose that organizational learning culture that emphasized care for the environment and the general good of all will mediate the relationship between CSR and OCB. This leads us to predict that:

Hypothesis 3: Organizational learning culture will be positively related to employee OCB.

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between employee perceptions of organizational CSR and employee OCB will be mediated by organizational learning culture.

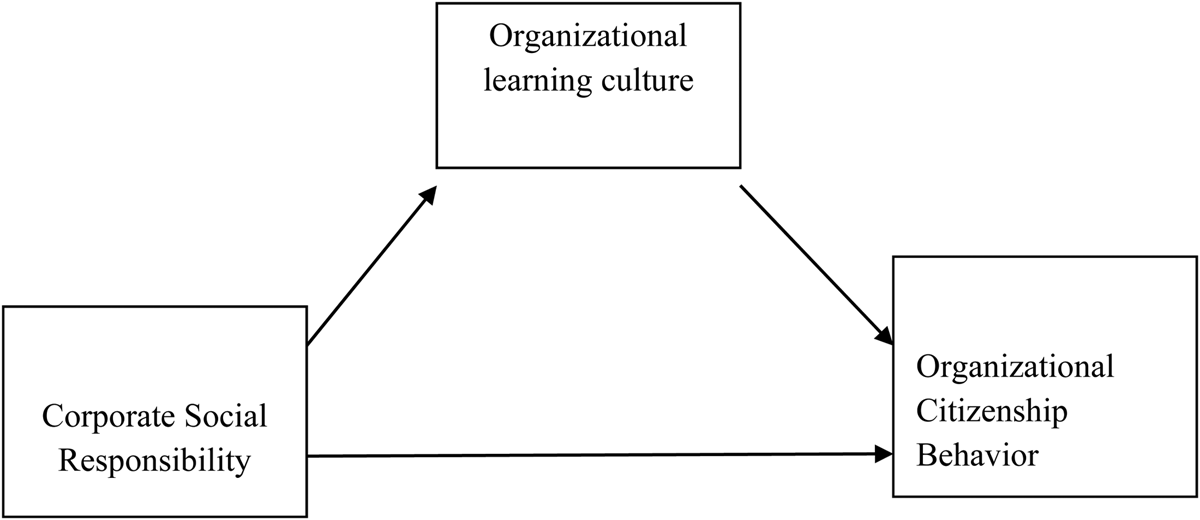

Our hypothesized model appears in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model of organizational learning culture as a mediator between CSR and OCB

METHODS

Research Design, Participants, and Procedure

A questionnaire was used to collect data relating to corporate citizenship, organizational learning culture, organizational citizenship behavior and demographic characteristics from corporate organizations in Nigeria. The complete set of the instruments were hand-delivered to 309 employees who agreed to participate in the study. Out of the 269 copies of the questionnaire that were returned (87.06% return rate) from the original 309 distributed, 15 copies were discarded because they were completed incorrectly, leaving 254 copies that were completed correctly and used for data analysis. In order to ensure anonymity of the responses, the questionnaire contained no provision for participant names and they were assured of confidentiality of their responses.

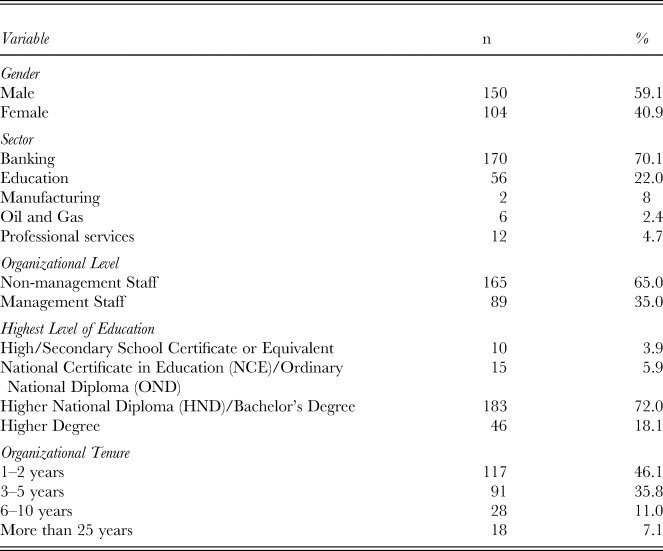

The sample, therefore, consisted of 254 (59.1% male) employees from varied occupational settings in Nigeria. They include: banking (170 or 70.1%), education (56 or 22.0%), manufacturing (2 or 0.8%), oil and gas (6 or 2.4%), and professional services (12 or 4.7). With respect to organizational level, 165 (65.0%) were non-management staff members and 89 (35.0%) were management staff members. Their educational qualification is as follows: High/secondary school certificate or equivalent (10 or 3.9%), National Certificate in Education (NCE)/Ordinary National Diploma (OND) (15 or 5.9%), Higher National Diploma (HND)/bachelor's degree (183 or 72.0%), higher degree (masters or PhD [46 or 18.1%]). As for organizational tenure, 117 (46.1%) had 1–2 years, 91 (35.8%) had 3–5 years, 28 (11.0%) had 6–10 years, and 18 (7.1%) had more than 25 years. They have spent averagely 3.39 years (SD = 2.47) on their current job. (see Table 1 for the demographics of the participants).

Table 1. Demographics of participants

Measures

Corporate citizenship measure

Corporate citizenship perceptions were assessed using 12 out of the 35-item measure developed by El Akremi et al. (Reference El Akremi, Gond, Swaen, De Roeck and Igalens2018). Our choice of 12 items out of the original 35 was borne out of the need to reduce constraints of completing a lengthy questionnaire and to minimize the likelihood of attrition (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006). The selected items were those with the strongest factor loading as reported by El Akremi and colleagues for the six dimensions of corporate citizenship which include, community, natural environment, employee, supplier, customer, and stakeholder-oriented CSR. Two items were selected from each of the six components based on this criterion. The scale has a 6-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Sample items included: ‘Our company invests in humanitarian projects’ and ‘Our company respects the financial interests of all its stakeholders’. Cronbach's alpha of the scale for the present study is 0.79.

Organizational citizenship behavior scale

We assessed OCB with a scale developed by Onyishi (Reference Onyishi2007) to measure OCB in a Nigerian sample. The eight-item OCB scale captures behaviors targeted at helping co-workers and those aimed at improving the organization which is consistent with other earlier scales on OCB (e.g., Williams & Anderson, Reference Williams and Anderson1991). The scale is scored on a five-point format (1 = never, 5 = very often). Sample items are: ‘I encourage my co-workers to learn new skills’, and ‘I initiate actions on how to improve the operations of my organization’. The scale has internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.81).

Organizational learning culture scale

We measured organizational learning culture with the 6-item of the Connect the Organization to its Environment sub-scale of the Learning Organization Questionnaire, developed by Marsick and Watkins (Reference Marsick and Watkins2003). It focuses on leadership behaviors that encourage learning among employees. The scale has a 6-point response format (1 = almost always, 6 = almost never). Sample items included: ‘In my organization, leaders ensure that the organization's actions are consistent with its values’ and ‘In my organization, leaders generally support requests for learning opportunities and training’. Cronbach's alpha of the scale for the present study is 0.83.

Data Analysis

First, we conducted a preliminary analysis to determine the means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study variables. Then, two hierarchical multiple regression analyses with organizational learning and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) as outcome variables, respectively, were used to test our main effect hypotheses. Regression-based path analysis based on 2,000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples was used to test our mediating effect hypothesis using PROCESS for SPSS macro version 2.13.2 (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). Mediation exists if zero is not in the 95% confidence interval (CI). Prior to testing the hypotheses, we conducted multicollinearity check. The results of our multicollinearity diagnosis showed that the tolerance levels ranged from 0.737 to 0.985, which are not less than .10. The variance inflation factors (VIF) ranged from 1.015 to 1.357, which are well below the multicollinearity threat threshold of 10 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2013). These are indications that multicollinearity is unlikely to influence the predictive relations in the present study (Tabachnick & Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2013).

RESULTS

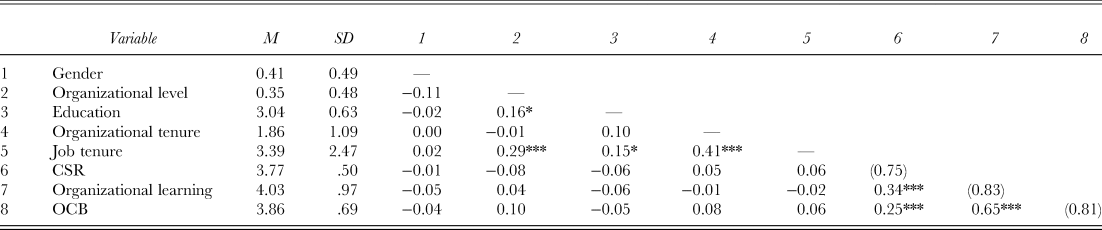

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and scale reliabilities based on Cronbach's alpha are shown in Table 2. As revealed in Table 2, all the scales displayed satisfactory levels of internal consistency reliabilities with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.79 to 0.83. Results from the simple linear and hierarchical multiple regression are presented in Tables 3 and 4, whereas results for the regression-based path analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, correlations, and scale reliabilities

Notes: N = 254, the values in parentheses along the diagonal are Cronbach's α for applicable scales, * = p < 0.05 (2-tailed), ** = p < 0.01 (2-tailed), *** = p < 0 .001 (2-tailed). CSR = corporate social responsibility, OCB = organizational citizenship behaviour. Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female; organizational level: 0 = non-management staff, 1 = management staff; education: 1 = High school/secondary school certificate or equivalent, 2 = NCE/OND, 3 = HND/bachelor's degree, 4 = higher degree; organizational tenure: 1 = 1–5 years, 2 = 6–10 years, 3 = 11–15 years, 4 = 16–20 years, 5 = more than 20 years, job tenure was coded in years such that higher scores represent greater job tenure.

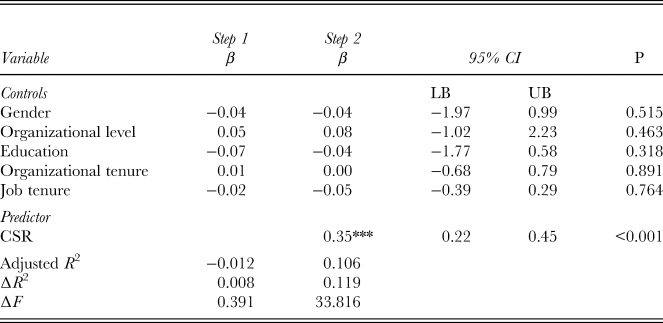

Table 3. Regression showing CSR as a predictor of organizational learning

Notes: *** = p < .001. CI = Confidence Interval, LB = Lower Bound, UB = Upper Bound.

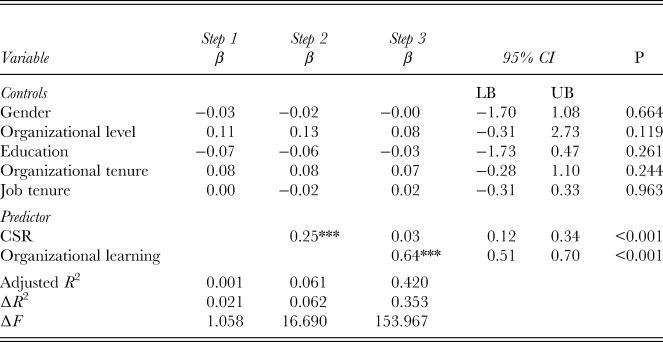

Table 4. Regression showing CSR and organizational learning as predictors of OCB

Note: *** = p < .001.

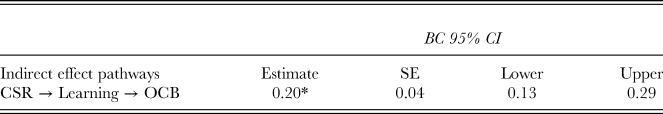

Table 5. Simple mediation role of organizational learning using path analysis

Notes: * = p < 0.05. BC = bias corrected, CI = confidence interval, CSR = corporate social responsibility, Learning = organizational learning culture, OCB = organizational citizenship behavior. BC bootstrapping results were based on 2,000 bootstrapped samples.

The results in Table 2 show that none of the demographic variables: gender (r = −0.04, p = 0.554), organizational level (r = 0.10, p = 0.122), education (r = −0.05, p = 0.462), organizational tenure (r = 0.08, p = 0.235), and job tenure (r = 0.06, p = 0.382) was significantly correlated with OCB. However, CSR was significantly and positively correlated with both organizational learning culture (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and OCB (r = 0.25, p < 0.001). There was also a significant positive correlation between organizational learning culture and OCB (r = 0.65, p < 0.001).

The results of the first hierarchical multiple regression in which organizational learning culture was the criterion variable in Table 3 indicate that none of the demographic variables entered as controls significantly predicted organizational learning culture: gender (β = −0.04, lower CI = −1.97, upper CI = 0.99, p = 0.515), organizational level (β = 0.05, lower CI = −1.02, upper CI = 2.23, p = 0.463), education (β = −0.07, lower CI = −1.77, upper CI = 0.58, p = 0.318), Organizational tenure (β = 0.01, lower CI = −0.68, upper CI = 0.79, p = 0.891), and job tenure (β = −0.02, lower CI = −0.39, upper CI = 0.29, p = 0.764). Collectively, the demographic variables accounted for only 1.2% variance in organizational learning culture. Furthermore, organizational learning culture was significantly and positively predicted by CSR (β = 0.35, lower CI = 0.22, upper CI = 0.45, p < 0 .001), with CSR accounting for 11.9% of variance in organizational learning culture over and above the demographic variables. Accordingly, H 2 was confirmed.

The results of the second hierarchical multiple regression in which OCB was the criterion variable in Table 4 indicate that none of the demographic variables entered as controls significantly predicted OCB: gender (β = −0.03, lower CI = −1.70, upper CI = 1.08, p = 0.664), organizational level (β = 0.11, lower CI = −0.31, upper CI = 2.73, p = 0.119), education (β = −0.07, lower CI = −1.73, upper CI = 0.47, p = 0.261), Organizational tenure (β = 0.08, lower CI = −0.28, upper CI = 1.10, p = 0.244), and job tenure (β = 0.00, lower CI = −0.31, upper CI = 0.33, p = 0.963. Collectively, the demographic variables accounted for only 0.1% variance in OCB. In addition, CSR was a significant positive predictor of OCB (β = 0.25, lower CI = 0.12, upper CI = 0.34, p < 0.001) and accounted for 6.2% variance in OCB. Hence, H 1 was confirmed. Organizational learning culture was also a significant positive predictor of OCB (β = 0.64, lower CI = 0.51, upper CI = 0.70, p < 0.001) and accounted for 35.3% incremental variance in OCB over and above the demographic variables, and CSR. Thus, H 3 was confirmed. Inspection of the results in Tables 3 and 4 based on Baron and Kenny's (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) mediation approach indicates that organizational learning culture mediates the relationship between CSR and OCB. We, however, decided to conduct regression-based path analysis following the strong reservations expressed by researchers (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013; Hayes & Preacher, Reference Hayes and Preacher2010, Reference Hayes and Preacher2014) on relying on the Baron and Kenny's approach for testing mediation. Thus, we needed to substantiate the Baron and Kenny's mediation approach by conducting regression-based path analysis (see Table 5).

The results of the regression-based path analysis in Table 5 was statistically different from zero (H4; bootstrap estimate = 0.20, lower CI = 0.13, upper CI = 0.29). This indicates that organizational learning culture was a mediator of the relationship between CSR and OCB. In this regard, H4 was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Employees are increasingly recognized as important stakeholders in corporate social responsibility (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Willness and Glavas2017). However, the mechanisms by which employees respond to CSR activities are still not clearly understood. The aim of our study was to examine the relationship between employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility and their engagement in organizational citizenship behavior; and to understand the role of organizational learning culture in this relationship. Our results confirmed our proposition that CSR is related to employees’ engagement in OCB and lend support to the social cognitive perspective that emphasizes the role of cognition in the formation of attitude and behavior. The results demonstrate that employees do make sense of their organization's CSR activities (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017; Basu & Palazzo, Reference Basu and Palazzo2008) and this enables them to develop a positive attitude towards the organization that leads to engagement in OCB. In line with other previous studies (e.g., Helm, Reference Helm2013; Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015; Santhosh & Baral, Reference Santhosh and Baral2015) our results confirm that CSR is relevant in understanding employee work behaviors. More specifically, the results are consistent with other findings across other cultures (e.g., Evans et al., Reference Evans, Goodman and Davis2011; Fu, Ye, & Law, Reference Fu, Ye and Law2014; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010; Rupp, Shao, Thornton, & Skarlicki, Reference Rupp, Shao, Thornton and Skarlicki2013) which reported that perceived CSR is positively related to OCBs. This demonstrates that Nigerian employees like employees in other countries are also motivated to engage in OCB by their organizations’ involvement in CSR activities.

Our results also confirmed our hypothesis that the organizational learning culture mediates the relationship between CSR and OCB. These results highlight the importance of learning culture in enhancing positive job behaviors and add to our current understanding of how CSR leads to OCB. An organization's engagement in CSR as shown in our results is related to organizational learning culture which then impacts on employee citizenship behavior. As earlier noted by Bates and Khasawneh (Reference Bates and Khasawneh2005), learning organizational culture is important for organizations as it enhances transfer climate that subsequently leads to improvement in productivity.

So, employees that engage in OCB operate at the same level of reasoning like employers who engage in CSR. Our findings therefore suggest that employers’ engagement in CSR is in congruence with employees’ expectations and therefore learn how to think beyond personal interest through their organizations’ engagement in such CSR activities. As Somech and Drach-Zahavy (Reference Somech and Drach-Zahavy2004) noted, learning enables the individual to overcome selfish interests and this facilitates their willingness to engage in extra role behaviors that support both other individuals in their organizations and their organization in general.

The finding that CSR relates to OCB extends our knowledge of how an organizations’ engagement in CSR could impact organizational performance through employee engagement in organizational citizenship behaviors. Previous studies on the relationship between CSR and organizational performance centered on customer satisfaction and financial performance of organizations (e.g., Luo & Bhattacharya, Reference Luo and Bhattacharya2006). The few studies that have attempted to look at how CSR affect employees have concentrated on issues relating to employee commitment and motivation (Gao & Yang, Reference Gao and Yang2016; Turker, Reference Turker2009). Our results show that employees can learn from their organizations to become better organizational citizens. In this sense, organizations that are good corporate citizens tend to produce employees who are also good organizational citizens. Organizations that engage in CSR are viewed by people including employees of these organizations as fair and just as they try to give back to the society through CSR activities. Employees in such organization make sense of these CSR activities (Aguinis & Glavas, Reference Aguinis and Glavas2017) and are motivated to mimic the organization. Through observation, imitation, and identification, employees become more willing to go beyond their job descriptions to exhibit behaviors that are congruent with their organization's interests (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; Rupp & Mallory, Reference Rupp and Mallory2015) such as being interested in what benefits others and the organization. They go the extra mile by engaging in OCB. The current study supports the notion that perceived CSR functions as a cognitive measure for desired behavioral expectations, in particular that employees believing that their employer have proven to be good neighbors are likely to engage in OCB that benefits the organization.

The observed link between CSR and employee citizenship behavior demonstrates that employees are interested in what their organizations do in relation to the environment and the society (Rodrigo & Arenas, Reference Rodrigo and Arenas2008). Our findings show that OCB does not just occur. Employees, through the processes of observation, socialization and subsequent identification that CSR provides, imbibe positive attitudes for discretional behaviors. As earlier noted, citizens in many developing countries look up to corporate organizations to support governments in these countries to provide some basic amenities that are often inadequate in most communities. The results suggest that CSR could become a strategic device for organizations in these countries to shape the positive work attitudes of their employees toward supporting the goals of the organizations. In other words, OCBs are not obtained by chance, rather they can be a product of what employees learn from their organization's ethical actions.

Social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura and Goslin1969) stipulates that the actions and policies of management can serve as role models for legitimate behaviors. Hence, organizations perceived as exhibiting CSR are more likely to reproduce that in the form of concern for others is a sanctioned mode of conduct. Thus, organizations that do not engage in CSR run the risk of having employees that have weak OCBs, and this may limit the progress of the organization. This is explicable because employees will be able to learn this ethical principle and transfer what they have learnt to their organization. When good CSR is perceived by employees, such practice is internalized, and employees will more likely see themselves as part of the organization, leading them to exhibit OCBs in the organization.

The confirmed mediating role of learning on the relationship between CSR and OCB also has some other practical implications. Communication of CSR activities to employees could become important in building a climate that encourages care to the society which in turn shapes the learning culture of the organization. The link between CSR and OCB occurs because organizational members have taken cues from their organizations and therefore organizations need to take deliberate actions to entrench learning cultures that support care for others and the society. Organizations could strengthen their learning culture, especially those related to attitudes toward the general good of the society, through engaging in activities that support fairness and justice to all stakeholders including customers, shareholders, the public, and their own employees. As noted by researchers (e.g., Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, Reference Du, Bhattacharya and Sen2010; Crane & Glozer, Reference Crane and Glozer2016), communication of CSR activities to stakeholders is a critical factor in maximizing the benefits of an organization's engagement in CSR. Employees are important stakeholders that should be adequately informed about an organization's CSR activities. Employees do care about how their organizations treat society (Rodrigo & Arenas, Reference Rodrigo and Arenas2008) and this in turn influences how they also care about the organization.

The fact that these findings are the same in Nigeria compared to the more advanced and strong institutional contexts where they are typically studied, allows us to meaningfully extend our understanding of CSR. We argue that given the peculiarities of the Nigerian context for CSR (Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adegbite and Rajwani2016), it is fair to assume that when organizations engage in CSR in Nigeria, they mainly do so with low or no intention to make profit from such activities; rather they do it to contribute to the society. In other words, the motivations for CSR are mainly normative – driven by values (Amaeshi et al., Reference Amaeshi, Adi, Ogbechie and Amao2006) – than by instrumental reasons of profit, since it is possible to make profit without reference to CSR. This is a very unique Nigerian context, which is remarkably different from developed and CSR enabling Western economies. It also flies in the face of Campbell (Reference Campbell2007)’s propositions that CSR would only occur in enabling contexts. It is therefore not surprising that in the same vein, since OCBs are behaviors that are not necessarily required by the employing organization and do not attract rewards, employee engagement in these behaviors comes from the inner conviction that there is a need to be selfless and willing to help others.

This reflects the prevailing collectivist culture in Nigeria. Collectivism orientation places emphasis on group harmony and group interests where individuals considers group interests above their personal interest and this is in contrast with individualism where people place individual interest and only considers group interest if it promotes individual goals (Ramamoorthy & Flood, Reference Ramamoorthy and Flood2002). In collectivists’ culture, individuals are more likely to expect not only to receive support from co-workers and supervisors; they also want the organizations to act in a manner that supports the general good of all the citizens. CSR then becomes a reflection of how organizations care for the society. Thus, in a business environment like Nigeria, the collectivists’ values tend to explain why individuals expect firms to engage in CSR and how perception of an organization's engagement in CSR activities shapes employees’ positive attitude toward the organization. Nonetheless, this is only a cautious interpretation, which will require further empirical works to consolidate. Obviously, context matters; but there is need to understand how different mechanisms in different contexts produce similar results and outcomes.

In addition, the findings show that in a country like Nigeria, where employees take fewer proactive measures to positively influence work outcomes (Onyishi & Ogbodo, Reference Onyishi and Ogbodo2012), engagement in CSR activities by an organization could influence employee positive perception of the organization. Such perception in turn can help employees to develop positive attitudes towards the organization including engagement in OCB. Thus, extending our understanding of the relationship between CSR and OCB as reported in other cultures (e.g., Evans et al., Reference Evans, Goodman and Davis2011; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen and Chiu2010) to developing countries of Africa is worthwhile. This underscores the notion that more research on the relationship between organizations’ practice of CSR and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior is needed.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

The present study, like most other previous studies, has some shortcomings that may provide opportunities for further studies in the area. The study was a cross-sectional study and data were collected at the same point. The issue of causality could not be established. In order to establish cause-effect relationship a longitudinal study is recommended. A longitudinal study would have helped in understanding how engagement in CSR over time influences organizational learning culture and how observed changes in CSR and learning culture shape employee engagement in organizational citizenship behavior. In addition to the issues relating to causality, information on all the variables in the study were collected using self-report, which raises concern on common method bias (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986). However, to reduce this bias, we adopted the procedural solution recommended by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) and ensured that participants’ responses were kept anonymous and confidential to minimize potential problems related to social desirability bias.

Although our study tried to uncover the mechanism by which CSR leads to OCB, it is also important to note that there may be other potential mediating and/or moderating variables in this relationship other than organizational learning culture. For instance, objective leadership behaviors may be important in ensuring that the organizational values are transferred to work teams (Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Siegel and Javidan2006) and this may also influence how CSR impacts employees and their engagement in OCB. It would be beneficial to extend our understanding of how CSR influences employee behaviors outside the workplace. Further studies could delve into how perception of CSR impacts employee willingness to help other citizens and the community – that is, becoming not only good corporate citizens but also good state citizens.

In addition, our study was done in Nigeria which has a peculiar business environment where many organizations struggle to cope with challenges including poor infrastructure and policies that support businesses. In this situation, engagement in CSR may not be a priority for many organizations. Yet, declining government spending and deteriorating public infrastructure in the country have made citizens look up to corporate organizations for intervention in provision of necessary social amenities (Ite, Reference Ite2004). In this situation, any attempt of an organization to engage in CSR could easily be noticed by employees. In this sense, the conclusions that could be drawn from the observed impact of CSR on employees should be interpreted with reasonable caution. Further studies on similar contexts will be very helpful here.

CONCLUSION

The study explored the relationship between organizations’ engagement in corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior. The mediating role of organizational learning culture in the relationship between CSR and OCB was also explored. The findings that an organization's engagement in CSR relates to its employees’ exhibition of OCB demonstrates that CSR is increasingly becoming not only a strategic device for an organization to increase its reputation in the society, but important in motivating employees to engage in extra-role work behaviors that could impact positively on organizational performance. A unique finding of our study that has not been found in any of previous research is that perceived CSR is positively related to OCBs through organizational learning culture that is present in the organization. This finding presents a new direction for future research to further evaluate the potential effects of learning on CSR and OCBs. We used the social cognitive theory to explain how employees can learn through their organization's activities in CSR to sacrifice self-interests and engage in organizational behaviors that directly benefit their co-workers and their own organizations. This generally demonstrates that organizations that engage in CSR also help their employees to think more broadly about their work contributions and could benefit from such activities by having workers who are willing to engage in extra role efforts.

APPENDIX I

Measurement Items

Corporate Social Responsibility

1. Our company invests in humanitarian projects

2. Our company provides financial support for humanitarian causes and charities

3. Our company takes action to reduce pollution related to its activities (e.g., choice of materials, eco-design, and dematerialization)

4. Our company contributes toward saving resources and energy (e.g., recycling waste management)

5. Our company implements policies that improve the well-being of its employees at work

6. Our company promotes the safety and health of its employees

7. Our company endeavors to ensure that all its suppliers (and subcontractors), wherever they may be, respect and apply current labor laws

8. Our company makes sure that its suppliers (and subcontractors) respect justice rules in their own workplaces

9. Our company checks the quality of goods and/or services provided to customers

10. Our company is helpful to customers and advises them about its products and /or services

11. Our company respects the financial interests of all its shareholders

12. Our company ensures that communication with shareholders is transparent and accurate

Organizational Learning Culture

In my organization, leaders:

1. Generally support requests for learning opportunities and training

2. Share up-to-date information with employees about competitors, industry trends, and organizational directions

3. Empower others to help carry out the organization's vision

4. Mentor and coach those they lead

5. Continually look for opportunities to learn

6. Ensure that the organization's actions are consistent with its values

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

1. I offer emotional support to my co-workers in times of problem

2. I encourage others to speak up at meetings

3. I make myself available to my co-workers to discuss their personal or professional problems they are facing

4. I encourage my co-workers to learn new skills and techniques

5. I find myself complaining about trivial matters

6. I attend and participate in meetings regarding the company

7. I initiate actions on how to improve the operations of the company

8. I attend functions that might not be required, which I feel might help the company's image