Introduction

In May to June 2007, on a visit with a group of postgraduate students of the Academy of Advanced Studies in Tripoli to the town of Bani Walid (Beni Ulid), Misratah province, ca. 180 km southeast of Tripoli and 100 km south-southeast of Tarhunah, Professor Elmayer recorded a cluster of five previously unpublished inscriptions, all of them Latin and three of them certainly Roman milestones. These stones were found lying on the ground in the western suburbs of the city, apparently having been collected up and put aside by the landowners in clearing their fields to grow crops on their farms.

The modern scientific study of the Roman road system of Tripolitania goes back to 1947, when Richard Goodchild of the Antiquities Department of the British Military Administration in Libya began the recording of numerous unpublished Roman milestones within the territory of Roman Tripolitania (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948), with a view to the eventual compilation of an archaeological map (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1954). He emphasised the importance of understanding the route network, as, he argued, the ‘roads were the life-lines of the military, administrative and commercial organisation of the province. Caravans carrying goods and wealth from central Africa to the cities, military detachments marching to garrison outposts in the pre-desert regions, loads of olive-oil passing from the Gebel to the ports – all this vital traffic passed along the road system developed from pre-existing trackways and officially incorporated at a relatively late date into the network of Roman imperial highways’ (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948, 5).

Goodchild (Reference Goodchild1948, 9–24; Reference Goodchild and Gadallah1968, 157–161) identified four principal routes on the basis of surviving milestones, which can be attributed to progressive phases of development (see Figure 1):

(a) the ‘Coast Road’, starting ultimately from Carthage and running from West to East through Sabratha, Oea (Tripoli), Lepcis Magna and round the bay of Syrtis to the frontier with the Roman province of Cyrenaica at the Ara Philaenorum;

(b) the ‘Eastern Jebel Road’ running south-west from Lepcis into the interior above the escarpment of the Eastern Jebel, initially laid out under Tiberius as far as Medinah Douga (Mesphe), then extended through Tarhunah to Ain Wif (Thenadassa) and Zintan (Tentheis) under Caracalla.

(c) the ‘Central Road’ along a route running southwards from Oea across the Jefara plain into the interior from Oea on the coast, through Mizda, and ultimately reaching the Fezzan; and

(d) the transverse ‘Upper Soffeg(g)in Road’ along the Upper Wadi Sawfajjin linking Zintan (Tentheis) on the Eastern Jebel road with the route to the Fezzan at Mizda.

Figure 1. Roman roads in Tripolitania. (Adapted from Zocchi Reference Zocchi2018, 52, fig. 1).

Goodchild (Reference Goodchild1948, 7; Reference Goodchild and Gadallah1968, 157–160), observed that in the interior, away from the Mediterranean coast, there was no evidence for any milestones being erected before AD 216 (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948, 7), when the Eastern Jebel, Central, and Upper Soffegin routes received milestones of Caracalla. This activity was part of a major campaign of upgrading and renewal across the whole of Africa Proconsularis (CIL VIII 21980) undertaken by the governor L. Marius Maximus Perpetuus Aurelianus (PIR 2 M 308; Salama Reference Salama and Desanges2010, 40). Goodchild further observed that in Tripolitania milestones belonging to the same series show a great deal of variation in size, shape and style of lettering, but they share an idiosyncrasy of design: in contrast to the milestones of Cyrenaica to the East and other areas of Latin North Africa to the West, which conform to the pattern common to the Roman world of columnar pillars with a cuboid base, in Tripolitania the milestones tend to comprise shafts sitting on separate recessed bases (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948, 7; Zocchi Reference Zocchi2018, 53). Notwithstanding the recent proposal, on the basis of a milestone base discovered on the outskirts of Lepcis (Zocchi Reference Zocchi2018, 66–68), to recognise an additional formal ‘Southern Road’ into the interior, the finds of inscribed milestones subsequent to Goodchild's studies (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948; Reference Goodchild and Gadallah1968; and Reference Goodchild and Reynolds1976), which has grown the corpus from an initial 40 to over 60 milestones, have not until now altered our understanding of the Roman road network that he established (see Appendix).

Modern Bani Walid, straddling a section of the upper Wadi Merdum, part of the Middle Wadi Sawfejjin basin, is one of the most substantial centres of the pre-desert zone of Tripolitania. Archaeology has demonstrated that this pre-desert zone, comprising steppe land punctuated by a series of wadis taking the water running off the Eastern Jebel to the salt marshes of the coast, was not developed for intensive sedentary agriculture until the Roman imperial period (Sjöström Reference Sjöström1993, 81–83; Elmayer Reference Elmayer1997, 203–206). This agricultural development was possible thanks to a system of farming that exploited the floodwater of the wadis and operated from the second century AD onwards from fortified farmsteads (centenaria in Latin, qsur in Arabic) with whose remains the landscape is dotted (Elmayer Reference Elmayer1984; Al-Dabeeb Reference Al-Dabeeb2019). However, this area of wadi farms around Bani Walid is not traversed by any of the routes first marked out under Caracalla.

Goodchild (Reference Goodchild1948, 28) had conjectured the existence of two possible informal ‘pistes’ converging on Bani Walid from the north, either from the Eastern Jebel Road in the area of Medina Douga (Mesphe) on the Tarhunah plateau or directly from Lepcis on the coast, while Pierre Salama proposed an alternative from Ain Wif (Thenadassa) on the Eastern Jebel Road (Desanges et al. Reference Desanges, Duval, Lepelley and Saint-Amans2010, Carte 5, N12-O12). It is then imagined that these routes led on south or southeast from Bani Walid to the Wadi Zemzem and possibly southeast to the vexillation fortlet at Abu Njaym/Bu Ngem (Gholaia) (e.g. Mackensen Reference Mackensen2021b, 113, fig. 1) or west to join the Central Road south from Mizda to the Severan vexillation fort at Qaryah al Garbiyah/Gheriat el-Garbia (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1954).

As it is, the sites catalogued in the environs of Bani Walid by the UNESCO Libyan Valleys Survey are generally dated to later Roman or Islamic phases (Sjöström Reference Sjöström1993, 186–189, nos 203–219 and 202–203, nos 265–271). The epigraphic culture of this pre-desert area in the Roman period is predominantly Latino-Punic (i.e. Late Punic written in the Latin alphabet and exhibiting some Latin loanwords) rather than Latin (Kerr Reference Kerr2010, 9–10). The epigraphic harvest in the immediate vicinity of Bani Walid itself has been relatively modest until now; consistent with the general pattern, the two texts already known are epitaphs, one Latino-Punic (LPE Wadi Ghalbun LP 1 = IRT 1220), the other Latin with Libyo-Punic names (Kerr Reference Kerr2010, 224 = IRT 1222 from the Wadi Ghurgar).

The following texts are edited on the basis of the transcriptions made and photographs taken by Professor Elmayer in 2007.

1. Milestone of Maximinus Thrax (figures 2 and 3)

Seen lying on the surface of the ground west of Bani Walid, presumably close to its original location. The upper part of an irregularly tapering and roughly worked column of local limestone, damaged to the right and top and broken off at the bottom. No dimensions are recorded. It is inscribed with a poorly executed Latin text with rather shallowly carved and irregular letters. The letter A frequently lacks a cross-bar but numbers are indicated by a supralineal line. The following edition is based on a tracing made of the text on site by Professor Elmayer and subsequently verified against the photographs.

Figure 2. Milestone of Maximinus Thrax. (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Figure 3. Milestone of Maximinus Thrax (detail showing lines 1–6). (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Diplomatic transcription

IMP CAES C[ ]IV [ ]

MAXIMINVS PIVS [ ]

AVGVSTVS GERMANICVS

MAXIMVS SAR[ ]ICVS

MAXIMVS DA[ ]IC[ ]S MAXI

MVS TRIBVNI[ ]IE POTESTA[ ]

III IMP VI ET C IVL[ ]

VS MAXIMVS NOBILISSI

MVS CAES PRINCEPS IOBEN

TVTIS GERMANICVS M[ ]

XIMVS SARMATI[ ]

Edition

Imp(erator) Caes(ar) C(aius) Iul[ius Verus] | Maximinu[s] Pius [Felix] | Augustus, Germanicus | maximus, Sar[mat]icus |5 maximus, Da[c]ic[u]s maxi|mus, tribuni[c]i<a>e potesta[tis] | III, imp(erator) VI et C(aius) Iul[ius Ver]|us Maximus nobilissi|mus Caes(ar), princeps ioben|10tutis, Germanicus m[a]|ximus, Sarmati[cus | maximus, Dacicus | maximus ---] | ------

Lines 9–10: iobentutis for iuuentutis.

Translation

The emperor Gaius lulius Maximinus Pious Fortunate Augustus, Germanicus maximus, Sarmaticus maximus, Dacicus maximus, with tribunician power for third time, hailed Imperator for the fifth (or sixth) time, and Gaius Iulius Maximus most noble Caesar, prince of youth, Germanicus maximus, Sarmaticus maximus, Dacicus maximus …

Commentary

Given its form, the column is very likely to have functioned as a milestone, and the text when complete to have originally celebrated restoration work by the emperor Maximinus Thrax. Although in its specific formulation this text is unique, it is very close to that common to a series of milestones erected right across Africa Proconsularis during the year of Maximinus’ third tribunician power (10 December 236–9 December 237: Salama Reference Salama and Desanges2010, 40–41; Kienast et al. Reference Kienast, Eck and Heil2017, 176) and attributing five or six imperatorial acclamations to the emperor.Footnote 1

Line 5. In the Bani Walid text the only significant deviation from the common pattern is the omission of Maximinus’ title of pontifex maximus, which, in all the other examples, appears between the last of the Augustus’ victory titles and the mention of his tribunician power. This omission is a sign of carelessness in the drafting of this text, readily explicable as a result of a simple saut de même au même (Dacicus <maximus, pontifex> maximus) in copying or dictating from the model text supplied.

Lines 9–10. In contrast to the visual error in line 5, the orthographic variant iobentutis for iuuentutis is a phonetic error. This spelling perhaps reflects contemporary regional pronunciation, combining the close-mid back rounded vowel (o) with a consonantal b/v,Footnote 2 in place of classical pronunciation, which would have followed the close back rounded vowel (u) with semi-vowel (w).

Lines 13-end. The African milestones of Maximinus end with various formulae commemorating repair work on the roads, though all the examples from the region of Tripolitania share the same wording, which we can be fairly confident was intended to read … pontes uetustate dilapsos et iter longa incuria corruptum restituerunt, sua infatigabili prouidentia peruium commeantibus reddiderunt (‘[Maximinus and Maximus …] repaired the bridges that had collapsed because of old age and the roadway damaged by long-standing neglect, and, by their untiring providence, restored passage along it to travellers’).Footnote 3 However, in the four Tripolitanian examples that preserve the reference to the damaged roadway (iter … corruptum), the more neutral attribution of the cause to the common topos of ‘long-standing neglect’ (longa incuria)Footnote 4 is replaced by a more aggrieved reference to ‘long-standing damaging action’ (longa iniuria: IRT 924–925, 934, 936). Clearly deriving from a misreading of the original formulation at some stage in its transmission, this curious variant apparently got established in the model text used for drafting the dedications of Maximinus’ milestones in the Tripolitanian region and so probably stood in the lost part of the new Bani Walid text too.

2. Milestone fragment (Figures 4 and 5)

An inscribed stone fragment lying on the ground near to the more complete milestone (no 1 above), representing the bottom half of a column. The text is inscribed on a finely chiselled surface in slightly irregular but elegantly carved capitals. There appears to be a supralineal mark (of abbreviation?) above the N in third line. The edition here is based on a transcription by Professor Elmayer subsequently checked against the photographs.

Figure 4. Milestone fragment found near no 1 (top lefthand). (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Figure. 5. Milestone fragment (top righthand). (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Diplomatic transcription

ES BIS COSS PA

OCOS MIL P

N LIII

Edition

------ | [--- trib(uniciae) | pot]es(tatis) bis, co(n)s{s}(ul), pa[ter patr(iae), | pr]oco(n)s(ul). Mil(ia) p(assuum) | n(umero) LIII.

Translation

‘… with tribunician power for the second time, consul, father of the fatherland, proconsul. Mile number 53.’

Commentary

Although the abbreviations in the text above have been resolved in the nominative, the dative would be equally possible. The supplements at the end of the first preserved line of the text are based on an assumption that the inscription was arranged around a central axis, indicated by the positioning of the distance figure. The palaeography suits a date in the second or third century AD.

Lines 1–2. The combination of iterated tenure of the tribunician power along with a single consulship could suit several candidates, including, for example, the emperor Tacitus, who does feature as trib. pot. II, cos. I on a milestone from the coast road between Oea and Lepcis (IRT 926). The order of titulature is very variable but the order tribunicia potestas, consul, pater patriae, proconsul is actually quite rare. However, it is found on a milestone of Gordian III from Fons Camerata in Numidia (CIL VIII 22396) and another in Africa Proconsularis on the road between Carthage and Theveste (AE 2013, 2087). Moreover, the rather unusual style with bis spelled out rather than indicated by a numeral (II) is found specifically in another Tripolitanian milestone of Gordian III (IRT 939b, from Borgo Tazzoli on the Eastern Jebel Road): Imp. Caes. M. Antonius Go|rdianus Pius | Felix Aug., pon|5tifex maximus, | tribuniciae po|testatis bis, p|ater patriae, | cos. Mil. p. |10 n. LVII.

Line 3. As observed by Goodchild (Reference Goodchild1948, 8), the formulation with n(umero) before the distance figure is an idiosyncrasy almost entirely confined to African milestones of the third century. In Tripolitania specifically it features on milestones of Caracalla (IRT 940–941, 944, 968), Maximinus and Maximus (IRT 946), Gordian III (IRT 939b, 942, 947), and Aurelian (IRT 943). However, almost without exception, numerus is used in the expression ‘mil(iarium) n(umero) [distance figure]’. Apart from the new Bani Walid text, the only other milestone to have the alternative formulation ‘m(ilia) p(assuum) n(umero) [distance figure]’ is that of Gordian III from Borgo Tazzoli (IRT 939b), quoted above. The distance total of 53 Roman miles (78.5 km) is too low to refer to a caput uiae at one of the cities on the Mediterranean coast, as was the case for the Eastern Jebel Road (measured from Lepcis) or the Central Road (measured from Oea). Instead, like the Upper Soffegin Road, which is measured from a junction with the Eastern Jebel Road somewhere near Zintan (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948, 21), the caput uiae of this road through Bani Walid must lie at some point in the Tripolitanian interior.

On balance, these considerations favour identifying the emperor in this fragmentary text also as Gordian III, in which case the milestone can be dated after 1 January 239, when he entered his first consulship, but before the end of his second tribunician power, which ran from 10 December 238 to 9 December 239 (Kienast et al. Reference Kienast, Eck and Heil2017, 187).

3. Inscribed fragment (Figure 6)

This stone fragment was seen lying on the surface of the ground near to no 1. The stone appears to be a column fragment cut down to create a rectangular block. Despite damage to the surface, traces of four lines can be discerned, of which three are preserved to full height. The reasonably regular lettering is executed in a simple capital script without serifs. The text here has been read by Dr Salway from the photograph.

Figure 6. Inscribed milestone fragment. (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Diplomatic transcription

U E˪

CTRBI

PATRI PATRI

MPLIII

Edition

------ | [---]Ọ[. .]EḶ[--- | Au]g̣(usto) tr(i)b(uniciae) p[otestatis --- | ---] patri patri[ae ---] | M(ilia) p(assuum) LIII.

Translation

‘[To the emperor …] Augustus, with tribunician power, father of the fatherland. 53 Miles.’

Commentary

Given the presence of a distance figure, this is certainly a fragment of the lower portion of another milestone. Even from the meagre surviving text, the milestone clearly bore a dedication to an emperor in the dative, which contrasts with the nominatives of the preceding two texts from the same location. Because of the damage it is not clear exactly how the text was disposed across the surface of the stone but the indication of the distance in the final line, which is certainly indented in relation to the preceding lines, may represent the central axis of the layout.

Line 1. If the first partially surviving letter on the top line is read as the bottom of an O, it is tempting to supplement the traces with the standard imperial epithets of the third century: [pi]ọ [f]el(ici) [inuicto]. If read as the bottom of a V, it is hard to understand the sequence [..]ụ[.]el[---] as belonging to imperial epithets or titles and easier to see them as traces of an emperor's gentilicium (i.e., [. A]ụ[r]el[io ---]) or cognomen (i.e., [A]ụ[r]el[iano ---]); see further discussion of dating (below).

Line 3. The imperial title pater patriae is, rather unusually, written out in full instead of abbreviated p. p. This rare fuller style is found elsewhere in the dedications of three Tripolitanian milestones from successive mile stations (56 and 57 respectively) on the Eastern Jebel road: twice in the nominative texts erected in the name of Gordian III (IRT 939b) and Philip the Arab (AE 1996, 1695 = IRT 1102) but perhaps more pertinently also in the rather incompetently inscribed dedication in the dative of a milestone to Claudius Gothicus (AE 1996, 1696 = IRT 1103): Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) | M. Aurelio | Claudio Vic|torị Aug(usto), | 5 tribuni⸢c⸣<i>e{t} potestate, | patri{ate} p(at)r|{r}(ie). M(ilia) LVII.

Line 4. If the distance figure is read correctly, then this stone came from the same mile station as the preceding one. On the implications of the figure for our understanding of the route it marked, see commentary to inscription no 2, line 3 (above) and conclusions (below).

If the first partially surviving letter on the top line is read as a V, although one could read [A]ụ[r]el[iano p. f. | Au]g̣(usto), given that two milestones were erected under Aurelian (AD 270–275) on the Central Road (IRT 943 and 953), the abbreviation of the epithets pius felix required to fit the lacuna do not sit comfortably with the spelling out of the title pater patriae in full when it is most commonly abbreviated p.p. Thus, although the traces of the first surviving line do not seem compatible with restoring a text directly paralleling the unique Victor Augustus style of IRT 1103, one could envisage restoring the Bani Walid text as another dedication to Claudius with a similarly rather truncated titulature (that is, without the epithets pius felix inuictus and the titles pontifex maximus and proconsul) but in a more regular style, e.g.:

[Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) | M. A]ụ[r]el[io Claudio | Au]g̣(usto), tr(i)b(uniciae) p[otestate], | patri patri[ae]. |5 M(ilia) p(assum) LIII.Footnote 5

If mention of the emperor's first (and only) consulship (1 January 269) is not simply lost in the lacuna before patri patri[ae] or just carelessly omitted by the drafter of the text, then the inscribing of this milestone dedication may be dated to the first three or four months of Claudius’ reign (September/October – December of AD 268: Kienast et al. Reference Kienast, Eck and Heil2017, 223). Such a dating would conform to the pattern observed by Eberhard Sauer (Reference Sauer2014, 274–278) for milestones from the period AD 235 to 306, which may be dated predominantly to the first few months of each new emperor's reign.

4. Funerary column (figure 7)

A column of local limestone found on the surface at a location to the west of Beni Walid, not far from milestone no 1 (no dimensions are recorded). The Latin text is laid out with some care and carved in lightly serifed letters that are elegant but slightly irregular in size.

Figure 7. Inscribed limestone column (detail of lines 3–7). (Photo: A. F. Elmayer, 2007).

Diplomatic text

MONIMENTVM

GRANIAE

FLACCILLAE

[S]ERVILIVS

CERIALIS

PIISSIMAE

VXORI

Edition

Monimentum | Graniae | Flaccillae | [S]eruilius |5 Cerialis | piissimae | uxori.

Translation

‘Servilius Cerialis (has erected this) memorial for his most pious wife Grania Flaccilla.’

Commentary

Line 1. As is clear from the very first word, monimentum (more regularly monumentum), this column is a funerary marker, which has been erected by a husband to his wife, both of whom appear, on the basis of their names, to be Roman citizens. Although a standard Latin term for a funerary monument, for instance featuring in the common epitaphic formula hoc monumentum heredem non sequetur (‘this monument should not pass to the heir’), the word monumentum is relatively unusual in this primary position. This usage is most typical of regions of central and northern Gaul (Lugdunensis, Belgica); otherwise, in Roman north Africa, as elsewhere, monumentum is more commonly found after the standard opening formula Dis manibus (e.g. IRT 677, 911, 980, 1121, 1137) and until recently was not found as the opening in Latin texts from the region of Tripolitania.Footnote 6 But another example has now come to light re-used in a late Roman qasr on the southwestern outskirts of Tarhunah in the Eastern Jebel (Mastino et al. Reference Mastino, Valente and Ganga2020, 169). This epitaph is dated by its editors to the late first century on the basis that the deceased, C. Valerius Romanus qui et Amasualath, derived his Roman citizenship from L. Valerius Catullus Messalinus (PIR 2 V 57), who may have been proconsul of Africa in the mid-80s AD.Footnote 7 The primary position of monumentum in these Latin epitaphs from Tripolitania is paralleled in the formula of a number of Punic language epitaphs from the Eastern Jebel and adjacent Pre-Desert area that begin with the corresponding Neo-Punic term mnṣbt (TRE Neo-Punic 55 = HNPI Tarhuna N1 = Elmayer 2020, 27) or its Latino-Punic equivalent mynsyft (IRT 873 = TRE LP 23 = LPE Gasr Doga LP 1; IRT 873 = TRE LP 2 = LPE Libya OU LP 1; AE 1998, 1515 = LPE Nawalia LP 1 = IRT 1216; LPE Wadi Chanafes LP 1 = IRT 1219; LPE Wadi Ghalbun LP 1 = IRT 1220).Footnote 8

Lines 2–5. At first glance the names of the deceased and her husband appear relatively banal. The gentilicia Granius and Servilius are quite well attested across Latin North Africa. Similarly the cognomen Flaccus and its derivatives (to which category the name Flaccilla belongs) and the cognomen Cerealis/Cerialis are both widespread in Latin North Africa. In the Tripolitanian hinterland two other Granii are already known from epigraphy: a Grania Hospita was commemorated in a pagan epitaph at the desert outpost of Legio III Augusta at Qaryah al Garbiyah (AE 1967, 543 = IRT 1116);Footnote 9 and, closer to Bani Walid, a Granius is invoked on an early Christian epitaph found in a late Roman qasr a few kilometres south-east of Al Qusayah (Italian Villaggio Marconi) on a section of the Tarhunah plateau (IRT 1131).Footnote 10 Despite the reasonably wide diffusion of both gentilicia, it is probably still significant that several members of both families are attested among the land-owning classes of Lepcis Magna on the coast. In her study of the origins of the élite families of Roman North Africa, Egbe Ifie identified the Granii of Lepcis as descendants of Italian settlers, whose members rose from the curial ranks to the senatorial order by the third century (Thompson Reference Thompson and Gadallah1968, 245; Ifie Reference Ifie1998, 83, 180).Footnote 11 By contrast, in the same study, the Seruilii are considered a family of native origin whose gentilicium is owed to M. Servilius Nonianus (PIR 2 S 590), proconsul of Africa under Claudius, probably in either AD 43–44 or 46–47 (Ifie Reference Ifie1998, 81).Footnote 12 Furthermore, Lepcis accounts for the largest number of attestations of the cognomen Cerealis/Cerialis within the entire province Africa Proconsularis.Footnote 13 In short, there is a very strong onomastic link between the married couple, Grania Flaccilla and Servilius Cerialis, and two of the leading families of the Roman élite of Lepcis Magna. The fact that Cerialis buried his wife Flaccilla here near Bani Walid suggests that they not only owned, but were also resident on, property here.

The palaeography and the fact that Cerialis gives his name without a praenomen favour a date in the second or third century for the erection of this epitaph.

5. Inscribed fragment (figure 8)

An inscribed stone, bearing parts of two lines of text, seen at another location near Bani Walid, not far from milestone no 3 (no dimensions are recorded). The location is at the summit of a hill overlooking a small village situated to the north. As in the funerary column (text no 4) above, the letters are reasonably elegantly carved, if a little irregular. There may be a punctuation mark, perhaps an ivy leaf (hedera) at the end of the second preserved line.

Figure 8. Detail of letters on inscribed fragment

Diplomatic transcription

IVS

IS

Edition

[---]ius | [---]is.

Commentary

The coincidence of the three preserved letters on the first line with the common termination of Roman masculine gentilicia means that it is tempting to restore one here, e.g. [Iul]ius. If this text is correctly interpreted as recording a Latin personal name in the nominative, then the letters on the second line might be understood as the remnant of a Latin cognomen of the third declension, such as [Natal]is, [Vital]is, or indeed [Cerial]is, as in the funerary column (no 4) above. The function of the monument to which this text belonged (e.g. religious dedication, funerary marker) remains undetermined.

Conclusions

The whole group of five inscriptions published here is significant as the earliest evidence for Latin epigraphic culture in the environs of Bani Walid. The newly identified milestones all certainly confirm the chronology outlined by Goodchild; that is that all the milestones from the interior of Tripolitania were erected under Caracalla or subsequent emperors of the third century. These new milestone finds are more significant for their location. Although they were not discovered in situ with their accompanying bases, the circumstances of their discovery suggest that they are unlikely to have moved more than a few hundred metres from their original locations. As such these milestones at Bani Walid are the first evidence for a formalised Roman road in the pre-desert zone east of Mizda. This improvement will have facilitated more efficient movement overland of troops, officials, official communications, and transport of goods in the area.

The chronology of the first two of the new milestones (AD 237 and 239 respectively) suggests that formalisation of the route through Bani Walid belongs to a distinct phase in the 230s. This infrastructural development was perhaps stimulated by, or went hand-in-hand with, an intensification of agricultural production in the area, in the wake of the development of the Limes Tripolitanus in the Severan period and further protected from the mid third century onwards by fortlets such as the nouum centenarium at Qasr Duib in the Upper Wadi Sawffejjin (inaugurated in AD 244/246: IRT 880) and Qasr Bularkan (Mselleten) to the east of Bani Walid (Mattingly Reference Mattingly1995, 80–95; Mackensen Reference Mackensen2021b). The evidence of the new funerary column suggests that this agricultural development may have been led by Latin-speaking farmers connected with the Romano-Punic élite of Lepcitan society. The possible dating of the third milestone to AD 268 suggests a continued interest in the route through Bani Walid that is consistent with the numismatic evidence for the continued occupation of the Severan fortlet at Abu Njaym into the mid-270s (Mackensen, Reference Mackensen2021a, 236–237).

If the distance figure on the second and third of the new milestones has been correctly deciphered, it seems likely that these three stones belonged to a cluster erected at the fifty-third mile on a road that was perhaps marked out formally for the first time under Maximinus Thrax. The distance of 53 Roman miles rules out the major coastal cities of Oea (Tripoli), over 150 km (100 Roman miles) to the northwest, or Lepcis Magna, about 100 km (67 Roman miles) due north, as the starting point for this route. Mizda, a similar distance (c. 100 km) to the west as the crow flies, also seems excluded. As with the Upper Soffegin Road, a caput uiae at some point on the Eastern Jebel Road seems most plausible for the road through Bani Walid. Goodchild's proposed route directly south from Qasr Douga (Mesphe) seems slightly too long at about 100 km. The distance is most suited to a formal marking out of Salama's ‘piste’ starting from Ain Wif (Thenadassa), about 80 km (54 Roman miles) to the northwest. The direction of the road beyond Bani Walid (southeast to Abu Njaym or south-southwest to Qaryah al Garbiyah and ultimately Sebha in the Fezzan) cannot be determined.

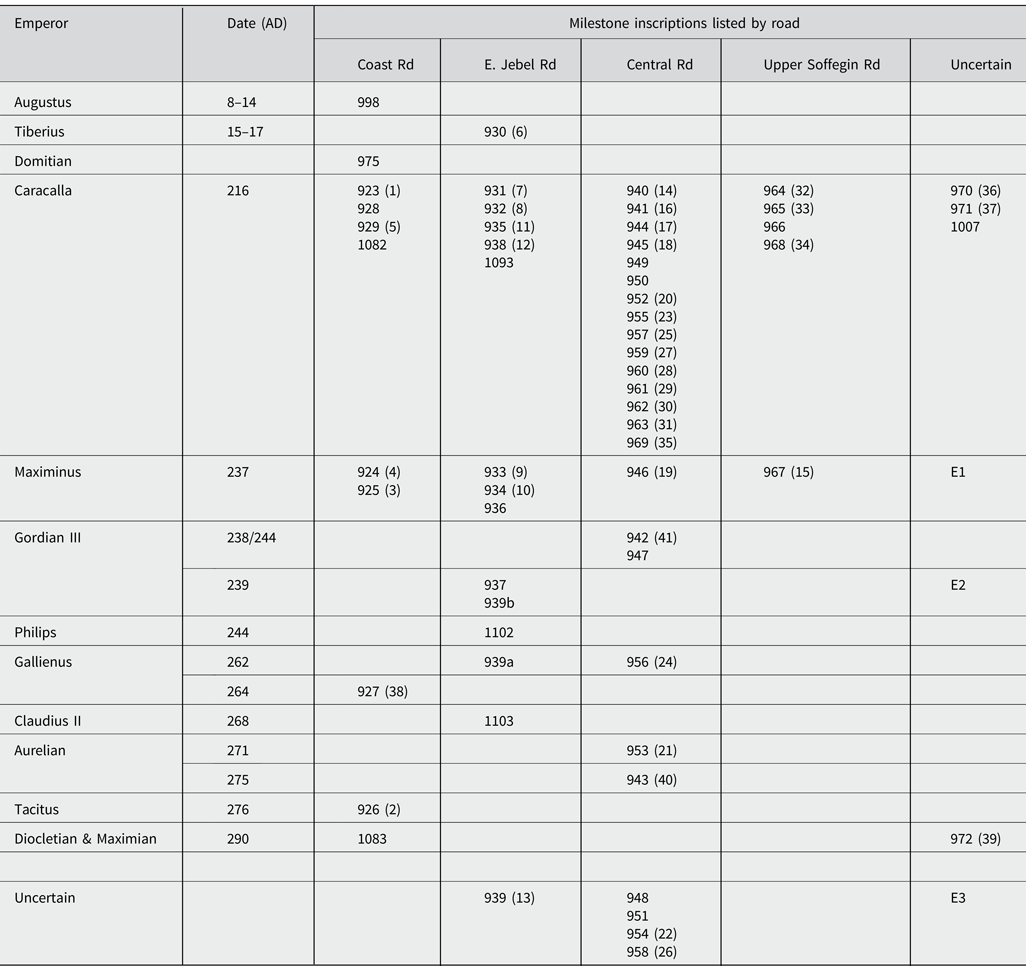

The discovery of a new Roman road in Tripolitania, combined with the recent release of the updated edition of Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania in 2021, permits consolidation in an appendix here of the milestone evidence for the Roman roads of the region in an update of Goodchild's useful synoptic table (Goodchild Reference Goodchild1948, 30).

Appendix: Chronological Table of Milestones of Roman Tripolitania

The principal reference numbers adopted for the milestones in the following table refer to their edition in IRT; where relevant, concordance to the original inventory of Goodchild (Reference Goodchild1948) is offered in parentheses (). The abbreviations E1, E2, E3 refer to the new discoveries by Professor Elmayer (nos 1–3 above).

Abbreviations

AE = L'Année épigraphique. Revue des publications épigraphiques relatives à l'antiquité romaine. Paris, 1888- .

BCTH = Bulletin Archéologique du Comité des Travaux Historiques. Paris, 1883- .

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, consilio et auctoritate Academiae litterarum regiae Borussicae editum. Berlin, 1863- .

HNPI = Jongeling Reference Jongeling2008. Texts available online at www.punic.co.uk/phoenician/neopunic-inscr/puninscr.html (accessed on 8 September 2022).

ILAfr = Cagnat, R., Merlin, A., Chatelain, L. Inscriptions latines d'Afrique (Tripolitaine, Tunisie, Maroc). E. Leroux, Paris, 1923.

ILAlg = Gsell, S. Inscriptions latines de l'Algérie. E. Champion, Paris, 1922–2003.

ILTun = Merlin, A. Inscriptions Latines de la Tunisie. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1944.

ILS = H. Dessau, Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae. Weidmann, Berlin, 1892–1916.

IRT = Reynolds, J. M. and Ward-Perkins, J.B. (eds). Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania. British School at Rome, Rome/London. 1952 + IRT2021: Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania (2021) by J. M. Reynolds, C. M. Roueché, G. Bodard, C. Barron et al. Available at: http://irt2021.inslib.kcl.ac.uk (accessed on 8 September 2022).

LPE = Kerr, R. M. Reference Kerr2010.

PIR 2 = Groag, E., Stein, A., et al. 1932–2015. Prosopographia Imperii Romani saec. I. II. III, edita consilio et auctoritate Academiae litterarum Borussicae, editio altera. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/Leipzig.

TRE = Elmayer 1997.