Description of the cave

This cave is located about 5 km northwest of the old city of Cyrene on the West bank of wadi Malja before it joins with the wadi Graga. Both wadis extend for approximately 13 km forming an estuary into the sea, west of the city of Sousa (Apollonia). It is about 750 m above sea level and overlooks an environment rich in a natural vegetation cover of wild olive, carob, and other natural trees and shrubs.

The rock shelter is a semicircular shaped rock cavity with dimensions of 10.55 m × 12.75 m and an opening of 10.64 m wide and 8.34 m height. The cave consists of white limestone and most of its walls are covered with a black layer resulting from water and fire traces. On the side of the cave, there is a circular opening in the wall separating the two caves with a 5-m long corridor before it connects with the other joining cave, which has an olive pressing basin and some hanging shelves in its walls.

Rock art works

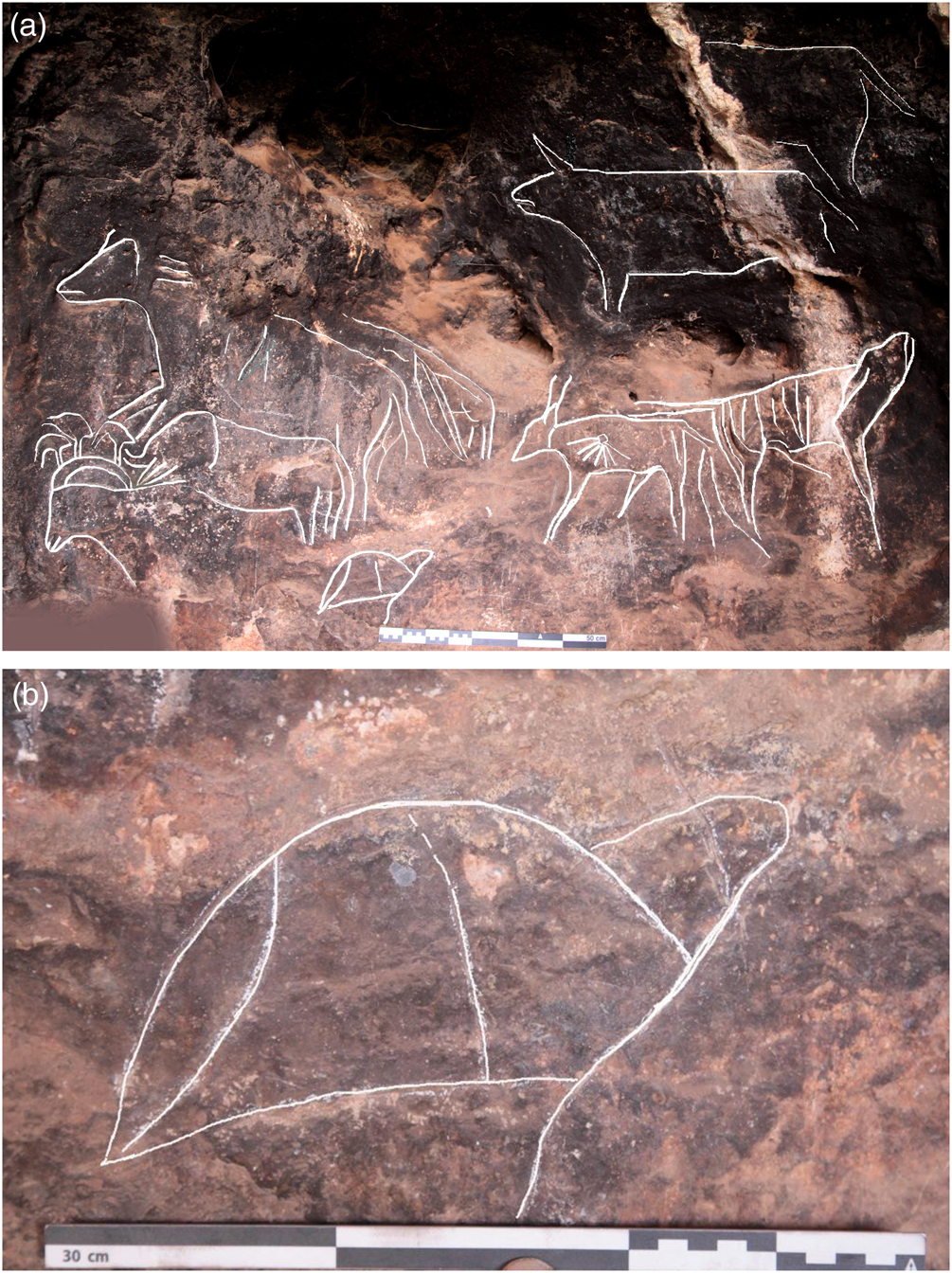

At the cave, the engravings without paintings were made on the inner wall and distributed into three groups in three places on the same wall. The first group (Figure 1) on the left of the entrance of the cave include the head of an aoudad, the head of a bull and the front of a horse's head. At an approximate distance of 4.10 m is a second group (Figure 2a) which is in the middle of the cave wall and contains a crowded scene of nine different animals, consisting of three cows, one of which is at the top of the engraving with only the back part visible and a wolf or a hyena and a gazelle that has a sunbeam in the centre of its body. There is also a head of an antelope, an elephant, a turtle (Figure 2b) and three small ostriches. In the centre there is an engraving with long, indistinct lines. Most of the animal heads are directed towards the west apart from the wolf and the turtle whose heads point to the east. The third group can be found at an approximate distance of 2.90 m (Figure 3) and represent an engraving with a body resembling a lion with its head pointing to the east, another engraving is unclear, and most are covered with a black layer. The phenomenon of stalactites and lack of space on the wall may have meant that the artist had to carry out his work on the old engravings and drawings resulting in overlapping engravings, though this can be common in rock art.

Figure 1. First group of engravings, showing the head of an aoudad, a bull and the front of a horse's head.

Figure 2. (a) Second group of engravings, showing a crowded scene of nine different animals, with (b) showing the sea turtle.

Figure 3. Third group of engravings, including possibly a lion.

The style of drawing is generally realistic when it comes to animals and is characterised by strong expression. The difference in styles suggests the likelihood more than one artist practised his artistic hobby on the cave wall. It is obvious there is more than one style and each style may refer to a certain period of time, with a particular method. The repetition of the side lines next to some engravings in the form of shadows for the cows, deer, elephant and horse head suggest the artist is symbolising the presence of more animals than those shown.

The artists' theme is restricted to animal life and most of these animals may have been living wildly and freely in the Green Mountain. For this reason it is believed the cows are of the wild type, while the antelopes are wild to this day. This is proven by McBurney's findings in his excavations at the Haua Fteah cave site, located about 25 km east of Al-Muqrinat. He found remains of wild cows and antelopes along with those of other animals including the rhinoceros, lion, the extinct African buffalo, and the striped donkey (zebra) (McBurney Reference McBurney1967). The work in the Haua Fteah by Graeme Barker also helped estimate the period at Al-Muqrinat, due to similar engravings and types of animals at their site (Barker et al. Reference Barker, Bennett, Farr, Hill, Hunt, Lucarini, Morales, Mutri, Prendergast, Pryor, Rabett, Reynolds, Spry-Marques and Twati2012). McBurney dated the findings to between c. 6,000–c. 7,000 BC. He attributed the engravings to the Qafsian artists who settled in the Green Mountain in Cyrenaica between c.6,000 and c. 10,000 BC and were known for their art of engraving on ostrich eggs.

Observations, comparisons and results

My first visit to the Al-Muqrinat Cave was at the beginning of 1994 to see the rock art, and further visits to the site continued more than once a year during the following 27 years (Figure 4). In September 1998 Mario Luni, Professor of Archeology at the University of Urbino and Director of the Italian Archaeological Mission to Cyrene, asked me to participate in fieldwork including a geological study of some sites in the region of Cyrene and its suburbs. We visited the site of the Al-Maqnarat Cave with members of the mission including geologists Oliviero Gessaroli and Paolo Busdraghi, for geological studies and some samples were taken for laboratory analysis in Italy, but the work was not completed.

Figure 4. Picture taking by Oliviero Gessaroli during the author's early visits to the cave.

I continued to visit the cave alone and sometimes with the archaeological researcher Abdulkarim Boghazaleh. On each visit, I took photographs, prepared paintings of the engravings in the form of sketches and artistic water colour paintings, to help the study and analysis of the rock art (Figure 5 and Figure 6). After reading the previous publications on the site, it was possible, through checks and comparisons, to show new engravings and make some corrections (such as the names of some animal engravings that differ from the description and designation published by Umberto Paradisi in Reference Paradisi1967). The turtle, for instance, has never been documented nor mentioned before. It could very well be a sea turtle due to the length of its front legs. Also, the wolf with its raised head pointing to the west and howling was described as a calf in previous studies, which I do not agree with. There is an engraving of the two-horned aoudad, which was also described previously as a calf. In the first group we see a horse's head facing west that has never been documented nor mentioned in previous studies. Next to it there is the head of a huge bull lowered in an attacking position and the head of a deer, which is very clear. In the third group, there is an incomplete engraving of an animal with a body resembling that of a lion and its head facing west, and at the bottom of it is an engraving of possibly a bird's head, with the rest of the body unclear.

Figure 5. Author taking sketches of the engravings.

Figure 6. Author documenting the engravings and taking photos.

Al-Muqrinat cave is considered one of the first rock art sites discovered in the Green Mountain in Cyrenaica and is characterised by the discovery of the first unique engraving of the turtle, wolf, aoudad, bull and horse. What also makes Al-Muqrinat cave special is the clarity and precision of the engravings on the rock wall.

The accompanying archaeological evidence

During a visit to the site in January 2010 following rain fall on the floor of the entrance to the cave in which there is a large pile of natural stones that accumulated on the surface of the earth, the details of the stones and their colours became clear, and some fragments of black pottery were discovered (Figure 7). A rough brown pottery was also found, as well as some ancient tools such as white flint stones (Figure 8) used as tools for grinding and making fires. Another discovery was a large and shiny flint stone with a green pigmentation mixed with grey (Figure 9) that is 28 cm in length and 14 cm in width, belonging to the core industry – the main stone for making tools. This kind of rock is called flint or chert, which is a sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline, the mineral form of silicon dioxide. It occurs as nodules, concretionary and as layered deposits. It breaks with a conchoidal fracture often producing sharp edges and can be found in small layers during the formation of Apollonia (Sousa).

Figure 7. Black pottery from the cave.

Figure 8. White flint stones found in the cave.

Figure 9. Core stone of flint, found in the cave.

In order to search for stone tools, visits to the site were repeated during the winter season, and, in December 2014, a rectangular flint stone (Figure 10) was found with a length of 20 cm and a width of 13 cm, on which a group of small points were engraved in three lines, one of which has nine points and another line next to it with six points and at the end of it four points in width and a straight line connecting the points with each other. It is a stone tool on which small points were recorded and it could be a calendar or a census record.

Figure 10. An engraved flint stone, found in the cave.

A rock was found in November 2017 with a similar idea and differs from the previous ones in that it was made from limestone (Figure 11), which is 13 cm long and 7 cm wide. It is also engraved with a straight line and at the end of this are the engraving of four circles of small points and five small triangles scattered – again possibly for recording something or as a calendar. Although not direct dating evidence for the rock art, these remains suggest the period above by McBurney and Barker for the Haua Fteah.

Figure 11. A limestone worked rock, found in the cave.

Conclusion and future research

During the last two visits to the site in April 2021, more photographs were taken and new drawings (Figure 12) were made. It was very clear that cracks on the wall were appearing. In the first group, one can clearly see the cracks on the back of the horse's head due to the high humidity, which is the result of the filtering of water from the top of the hill of the cave into the inner wall of the engraving. The second group of engravings also sustained cracks in the rock wall of the cave. Some pieces are beginning to fall especially in the middle of the body of the gazelle, the elephant and in the part of the back of the cow. The wall on which the engravings appear is in urgent need of restoration work, which can be done by injecting the cracks with special adhesives that suit the environment and the condition of the cave wall rocks in order to install, contain, protect and preserve the engravings. This extremely vital and neglected cave needs further study and research. The current condition of the site is not sustainable and maintenance must be carried out. This field work comes during a very challenging time and if the correct steps are not taken the whole site could be in great danger and possibly lost. A laboratory analysis to determine the correct historical period is also vital, bearing in mind the importance of this site not only in Cyrenaica, North Africa, but in the whole Mediterranean Basin.

Figure 12. Author's artistic impression of the cave.