1. Introduction

The margin of appreciation has appeared in case law interpreting the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) ever since it first came into force. The first usage was by the European Commission of Human Rights Footnote 1 and the doctrine was since developed further by the European Court of Human Rights (the Court or ECtHR). What, however, has been confounding scholars continuously since the 1990s, is its exact role in adjudication. Footnote 2 In recent debates concerning the Interlaken reform,Footnote 3 the margin of appreciation was called for explicitly in each of the Declarations from the Committee of Ministers (Declarations). Footnote 4 In the Brighton, Brussels and Copenhagen Declarations especially, the ‘further development’ and ‘consistent application’ of the doctrine was ‘welcomed’ and ‘encouraged’. Footnote 5 The Brighton Declaration, in fact, resulted directly in the drafting of Protocol 15 which inserts the margin in the preamble of the Convention and which, due to a delay in ratifications, has only come into force in August 2021. The Declarations indirectly prescribe an increased or improved usage as a remedy to the Court’s challenges with backlog and backlash. Footnote 6 The British Prime Minister at the time of the Brighton Declaration, David Cameron, explicated these claims and goals, arguing that the Declaration would require the Court to:

… take more account of the principles of subsidiarity and the margin of appreciation in its decision-making, both to allow national authorities to reach conclusions based on their own particular circumstances, but also to reduce the ever-increasing workload of the Court. Footnote 7

Cameron is quoted here because his statement synthesizes the debate at the time into two clear claims. First, that the usage of the margin should be increased to allow states to make more decisions for themselves. Second, that increased usage would reduce the caseload of the Court. The first statement engages with normative questions regarding the optimal balance between human rights universality and locality in application, which have been debated extensively since the advent of international human rights law,Footnote 8 but it also contains an empirical claim, namely that an increased usage of the margin of appreciation in the Court’s interpretation would lead to more elbowroom for states. Prima facie, this claim seems logical, but it has not actually been confirmed empirically, and doctrinal literature has already produced many examples where it has not been the case.Footnote 9 The second claim, that increased subsidiarity would lessen the Court’s workload, is much less straightforward and would, in any case, be working indirectly. As a result, it has already been challenged in the literature.Footnote 10 This article will therefore limit itself to empirically testing the first claim, namely whether an increased usage of the margin of appreciation would result in more ‘elbow room’ for or deference to states.

The question is an important one because even though the connection has been questioned in some of the doctrinal literature, it has been relied heavily on by actors at the Court in general, in particular in connection with the Interlaken reform process. For example, in 2009 the English Lord of Appeal, Lord Hoffmann, voiced a scathing critique of the ECtHR arguing that the Court should increase its usage of the margin of appreciation, Footnote 11 or risk losing its legitimacy. Footnote 12 When, in 2014, ECtHR Judge Spano – now President Spano – decided to respond to this legitimacy challenge, he surprisingly did not argue that the critique was misplaced because of the universality of human rights or legitimate foundations of the Court, Footnote 13 but rather because ‘the Court is [already] in the process of developing a more robust and coherent concept of subsidiarity as well as attempting to reformulate the conditions for allocating deference to the Contracting States’. Footnote 14 In 2018, now citing a quantitative study by Mikael Rask Madsen showing that the language of the margin of appreciation had been rising since 2010, he reiterated this claim. Footnote 15 This study and the claim that the margin was being used ever more, was central in the political debates surrounding the drafting of the Copenhagen Declaration. Specifically, preprints of Spano’s 2018 article were circulated among the team responsible for the preparatory works for the drafting of the Copenhagen Declaration.Footnote 16 This particular (qualitatively contested) understanding of the margin was thus part of the foundation of knowledge for the politicians and civil servants drafting the Draft Copenhagen Declaration.Footnote 17

When literature attempting to test the connection empirically is scarce, it is because studying it is an exceedingly difficult endeavour. Madsen’s oft-cited study was innovative, especially at the time, but the abducted corpus-linguistic methodology it applied; counting the occurrence of the expression ‘margin of appreciation’ per million words,Footnote 18 tells us nothing about whether these mentions are accompanied by increased deference to states. One methodological problem with discovering the link between the margin and deference is that there is little agreement in the academic literature about both sides of that equation, namely what exactly the margin of appreciation does and how it can be recognized, and what exactly ‘elbow room’ or deference to High Contracting parties might look like. The Court itself has also not provided definitions of either. As a result, the language of deference may take many different forms. There also appear to be instances in which the Court uses the margin language but without applying deference, in the doctrinal literature referred to as ‘empty’ uses of the margin.Footnote 19

Similarly, because adjudication is a task which includes a multitude of factors which are not always explicated, there may also be instances where deference is applied in the initial determination of the scope of the right,Footnote 20 or where it is applied implicitly without including a mention of deference. This article will attempt to create a bridge between the empirical/quantitative studies of the margin and the doctrinal studies. This will be done by conducting a transparent mixed-methods study of the margin of appreciation, which applies both high-abstraction level statistics and lower abstraction level doctrinal analysis as a sample study to address some of the concerns raised when attempting to study the margin statistically. This article aims to identify some sources of false negatives, that is, cases where deference is applied but which are unlikely to be picked up by statistical methods, but its main analytical focus is on false positives, i.e., cases where the margin of appreciation language appears but where it is not followed by increased deference to the High Contracting parties.

The article will proceed as follows: Section 2 will situate the study in the existing literature and explicate how theories on the margin of appreciation have contributed to forming the research questions. This will be followed by Section 3 on the methodology applied and the proxies used. Hereafter, Section 4 will follow, consisting of a high-abstraction level mapping of the relative prevalence of margin of appreciation language in caselaw from 1960 until 2021, and an overview of a high abstraction-level deference determination in the form of case results in admissibility or violation/non-violation judgments. Section 5 presents a lower abstraction level study opening the black box of the individual cases reviewing which actors are using the margin of appreciation language and how – resulting in an estimate of the amount of ‘empty’ margin of appreciation mentions we might expect to see. Together these two analyses give a better insight into what a linguistic mention of the margin means statistically, laying the ground for Section 6, which tests whether the use of the language of the margin of appreciation is a predictor of the amount of deference afforded to states.

2. Theories and research questions informed by the state of the art

… State authorities are in principle in a better position than the international judge to give an opinion … [this] leaves to the Contracting States a margin of appreciation … The domestic margin of appreciation … goes hand in hand with a European supervision … It is in no way the Court’s task to take the place of the competent national courts but rather to review … the decisions they delivered.Footnote 21

The above quote is from the Handyside case from 1976, which is widely recognized in the literature as a key case in which the margin of appreciation gained a more explicit articulation building on previous expressions of the margin of appreciation in Article 15 cases on declarations of emergency and previous discussions on subsidiarity in for example the Belgian Linguistics case from 1968.Footnote 22 This is, however, more or less where the general agreement ends. Normative discussions on the topic have been particularly rich, encompassing whether the margin is ‘the “natural product” of the distribution of powers between the Convention instruments and the national authorities’,Footnote 23 or rather a ‘principled recognition of moral relativism [that] is at odds with the concept of the universality of human rights’.Footnote 24 As have definitional discussions on whether the margin has a clear albeit complex doctrinal usage,Footnote 25 or should rather be considered a strategic instrument that the Court can put to use as a ‘convenient way to dispose of cases’,Footnote 26 or to please difficult states.Footnote 27 These types of normative discussions are to be expected for a doctrine that delimits the boundaries of international control with national legislation and administration, but literature on the margin is also not in agreement about foundational descriptive facts. There are, thus, examples of literature that operates with a margin which is applied as part of the proportionality assessment, whether before,Footnote 28 incorporated,Footnote 29 or as a final weighing of all things considered.Footnote 30 While another body of literature works with a margin determined foremost by the right it is applied to,Footnote 31 the type of applicant,Footnote 32 or whether cases include economic and social policies.Footnote 33 Yet another body investigates the relationship between the margin and the level of interference with the essence of the right,Footnote 34 with European consensus,Footnote 35 or with procedural protections at the national level,Footnote 36 or the quality of the democratic debate nationally.Footnote 37 Together the literature presents a wealth of different influences on the width and application of the margin, going some way to explaining both why the doctrine is difficult to quantify, having often been described as unclearFootnote 38 or elusive,Footnote 39 and why works presenting the doctrine as not one but several concepts have been so illuminating.Footnote 40

As a whole, the literature operates with some connection between deference and the margin of appreciation, but also demonstrates a high level of complexity affecting this connection. This is contrasted by the clear political insistence on a ‘more robust’ application of the doctrine in the political Declarations in the Interlaken Process. The political Declarations issued by the High Contracting Parties were not without political and soft-power costs, and their negotiations took months.Footnote 41 The reason for this insistence was, without any doubt, that central political actors expected an increased usage of the margin to result in more deference to states – or put more simply, in more state wins.Footnote 42 This expectation was likely reinforced by the president of the Court’s notion of the Court having entered an ‘Age of Subsidiarity’. Footnote 43 There is, thus, a gap between the qualitative studies of the margin of appreciation and the political assumptions about the margin which are partially supported by quantitative studies. It is this gap that this article will venture to fill.

On the basis of the discussions referenced above, this article will investigate the following research questions:

R1: Which actors are the most frequent users of which kind of margin of appreciation language? The question is an important one mainly because it determines limitations on to what extent margin-language is likely to be an indicator that the Court considers the questions of deference and subsidiarity relevant in the present case. Since if the respondent states or even intervening third-parties are the most frequent users, this might be seen solely as an adjudicative strategy, whereas if the Court is the most frequent applier, it would be more reasonable to assume that the margin-language would be connected to the application of the doctrine in legal reasoning. This question also includes whether margins are wide, narrow, or used without an indicator of the width.

R2: How frequent are ‘empty’ mentions of the margin? This question is connected with the previous one. The presumed connection between margin language and actual application of the margin-doctrine (which is one assumption on which qualitative and quantitative studies currently clash), can be established by reviewing what kinds of arguments the margin is connected with, how often a narrow margin is advocated as opposed to a wide one, and whether the margin is applied as part of the scope, the proportionality assessment, or the procedural review. Together these elements will result in an assessment of the relative prevalence of empty margin uses which one would not expect to impact the whether a judgment results in a violation or non-violation result.

R3: Are ‘margin cases’ more likely to result in state wins than non-margin cases? This is the main research question, the investigation of which is tempered and informed by the answers to R1 and R2. In this case, ‘state win’ is used as a proxy for ‘state deference’. While the two are most certainly not the same – the Court may well find a violation in a case even in an area where there is usually a high level of deference if the inference with the right is intense. There are also many cases that states can win without invoking a deference-argument (though these will often be declared clearly inadmissible) – but in the aggregate, for the group of cases where a delicate balancing is undertaken, if the margin is connected with increased deference, it should also result in higher numbers of state wins. On the basis of the ‘delicate balancing’ element in this argument, this article furthers a hypothesis, namely that both margin-mentions and state wins are likely to be more common in ‘hard cases’ than in other cases. Hard cases here are defined as those that are neither obviously inadmissible nor obvious violations in line with the existing case law. Proxies for these hard cases may be the higher importance-level, key- and level one and, to a lesser extent level two, the presence of a separate opinion, or treatment by the Grand Chamber. These variables are in turn somewhat colinear. Almost all Grand Chamber cases are key- or level one, while on the flipside only about a quarter of Key- and Level 1 cases have been treated in the Grand Chamber.

3. Methodology

The analysis in this article relies on a mixed qualitative-quantitative approach engaging with several different types of data. It contains several different levels of abstraction. At the highest abstraction level there are statistical analyses of an almost complete body of caselaw, while at the middle-lower level I have analysed a sample of 202 key- and level one cases containing at least one mention of the margin of appreciation. The reason for conducting the analysis in this way is to avoid conscious or unconscious cherry-picking of a particular type of case, whether those with a particular usage of the margin or those against a particular country or similar. The point is also to get a complete overview of the caselaw since the very different experiences of the degree of deference afforded to states by different political actors, different scholars, applicants, and national authorities may well be due to the different populations of cases that reach these groups. This will be explained in detail in Section 4.

The highest abstraction level statistical analysis will take place using the yearly reports of caselaw statistics published by the Court,Footnote 44 followed by case law searches conducted in the HUDOC database,Footnote 45 and analyses on an existing dataset made public by Voeten and Stiansen.Footnote 46 The benefit of this triad is that each set brings something different. The Court’s statistical reports include numbers on the inadmissibility cases and administratively rejected cases which are not published in HUDOC, but no detail on the individual cases, while HUDOC has every judgment and decision made in a Chamber or Committee. The Voeten-Stiansen Dataset is a scraping of metadata on almost all (21,954) judgments (but no decisions) published in English between 1960 and 2019, and it has the benefit of being malleable to a greater extent, allowing for more targeted statistical analysis. In both the study of the HUDOC database and the Voeten-Stiansen Dataset, the study looks for simple margin-mentions; ‘margin of appreciation’ or ‘margin of discretion’ rather than ‘wide’ or ‘narrow’ margins, which will instead be studied at the lower abstraction level to inform the high abstraction level study.

For the lower abstraction level, I have created a sample of all 202 key- and level one ‘margin of appreciation cases’Footnote 47 issued between 23 February 2012Footnote 48 and 1 January 2020. These cases are coded for when the margin of appreciation language is used and whether it is ‘wide margin’, ‘margin’ or ‘narrow margin’, what it is used for, and whether submissions came from the applicants, governments, third parties, the Court’s own assessment, or separate opinions.Footnote 49 When coding what the margin is used for, I have attempted to keep this as simple as possible to avoid situations where the determination is unclear. The categories are (i) empty mentions,Footnote 50 (ii) anti-margin mentions, (iii) the margin as part of the scope, (iv) the margin as something that should be granted to certain domestic institutions, (v) the margin as part of the proportionality assessment, (vi) the margin as a ‘better placed’ argument, and (vii) ‘other’. For each of these codes, except the last, there are sub-categories.Footnote 51 The coding is done so that each margin-argument has only one code. Still, a single case may contain several mentions of the margin by several different actors, each of which can be coded differently. The 202 cases act as a sample, though not a random one, to indicate how often margin-mentions are, in fact, narrow margins, and how often a case might appear as a ‘margin-case’ in the statistical analysis while it is actually only non-court actors that are engaging with the margin or where the main argument is that the margin is not relevant in the present case. It is important to keep in mind, that the 202 level one and key-cases are not representative of the total population of applications to the Court or even the total population of judgments. Cases at the different importance levels – which are curated by the Bureau of the Court in collaboration with the JurisconsultFootnote 52 – are likely to be different because they treat different types of cases. In this article, key cases and case reports will be treated as one category. The Court used the terminology ‘Case Reports’ between 1998 and 2015 when the most important cases were published in the ECHR Series of Judgments and Decisions while from 2007 these cases started being named ‘Key cases’ in the HUDOC database, and since 2015 ‘Key cases’ has been used to label both types in the database.Footnote 53 The Bureau classifies level one cases as ‘high-importance judgments, decisions and advisory opinions not selected for the Case Reports but which nevertheless make a significant contribution to the development, clarification or modification of the Court’s case-law’. It was also the highest level before the introduction of Case Reports. Levels two and three, on the other hand, are considered of lesser importance, but where level three cases only apply well-established caselaw, level two cases can go beyond this and may therefore still be relevant precedents for specific cases. There are big differences in the prevalence of each type of case. HUDOC lists, as of December 2021 in English, 1,364 key cases, 1,560 level one cases, 5,796 level two cases and a total of 44,677 level three cases. The reason for using high importance-level cases for the sample is that these are more likely to contain a wealth of different or innovative uses of the margin, whereas lower-level cases are more likely to contain margin-mentions that refer to older higher-level cases. For the purpose of understanding the many different types of uses that might be found in the population of cases as a whole, this sample is therefore superior to a random sample which would be likely to consist of at least 80 per cent of level three cases. The sample will therefore form the foundation first and foremost for the answering of R1 and R2.

Attempting to count how often different actors use the margin comes with several important caveats, and the results carry with them some uncertainty. The caveats include that the arguments published in the judgments and decisions which form the corpus of this study, are not the original arguments and allegations submitted by the parties, but the Court’s summary of them. Therefore, it is not inconceivable that governments or applicants may in some cases, have mentioned the margin of appreciation, but this has not been reflected in the final written version of the proceedings. Presumably, however, this should exclude only less likely cases, that is cases where the margin did not play a large role; otherwise, one would expect either the Court to mention the doctrine itself or the parties to protest its absence in deliberations. Another important caveat for testing whether the usage of the margin of appreciation language results in more state deference in the form of state wins is that written judgments are not optimal data for quantitative analysis. Judicial reasoning relies on a range of factors related to the case at hand including the right in question, the degree of interference, the legitimate aim, vulnerability of the applicant, and many more, of which the margin of appreciation only encapsulates some.

Furthermore, judgments do not always result clearly in one result or another, oftentimes some elements of the case are inadmissible, whilst others are violations and non-violations. It is not uncommon for a case to result in both violation– and non-violation decisions regarding the same article for different parts of the course of events. Footnote 54 In some social science studies of the ECtHR, this problem has been solved by creating a unit of analysis of ‘at least one violation-decision’,Footnote 55 and while this can work for some studies, it does not give a full picture of the relative tendency of deference which this study is attempting to capture. It also misses the fact that often from Chamber to Grand Chamber the number and types of articles that are found to be in violation or non-violation may change in ways that absolutely affect the perception of how stringent the Court is. A recent example of this is Savran v. Denmark where an Article 3 violation in the Chamber was translated into an Article 8 violation in the Grand Chamber, a change interpreted as a win by the Danish authorities.Footnote 56 In this article, the problem of several decisions in a single judgment will instead be addressed to some extent by making the individual decision the unit of analysis for some of the calculations, rather than the case.Footnote 57 The most important way this article attempts to address these shortcomings, however, is by not abandoning the qualitative, doctrinal method altogether. It relies on a strict differentiation between linguistic use, which can be measured quantitatively, and adjudicative importance, which demands a legal analysis, and utilizes the methodologies together to reach robust conclusions.

4. Margin and deference over time: The highest abstraction level analysis

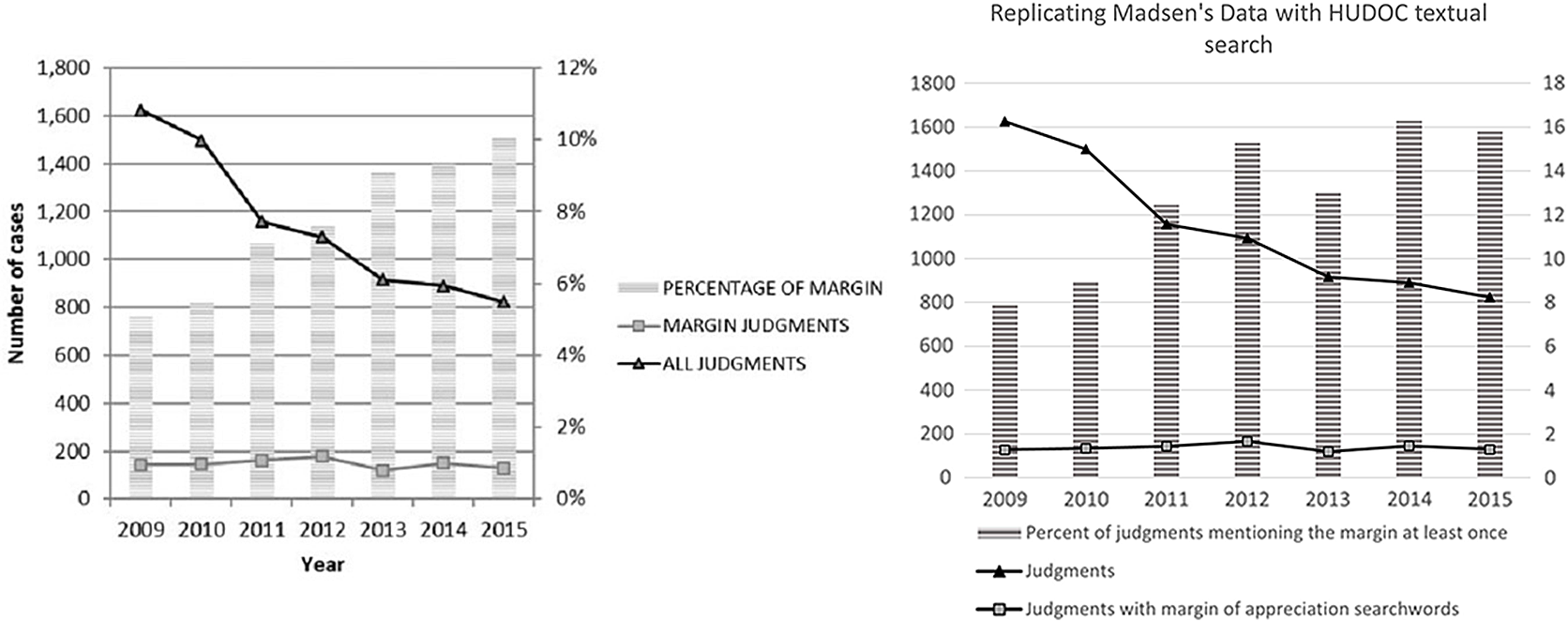

As indicated in the introduction, the claim that the Court is applying the margin of appreciation more often in its case law has been central in much of the debate surrounding the reform. Many scholars relying on this premise cite the same source, a quantitative study by Mikael Rask Madsen from 2018, and certainly, Madsen’s data suggest a clear narrative (see Figure 1): the percentage of margin of appreciation cases appears to be rising steadily while the output of the Court is falling. With the use of a textual searchFootnote 58 for the ‘margin of appreciation’ in the HUDOC database, the data is generally replicable.Footnote 59

Figure 1. Relative prevalence of margin-cases 2009–2015, replicating Madsen’s study.

The left-hand axis denotes the number of judgments per year while the right-hand indicates the percentage of judgments containing a mention of the margin of appreciation.

Madsen’s study, for reasons of scope and comparability, covered a narrow timeframe of just six years. Taking instead a temporally broader view, and with the benefit of another five years passing, the trend appears much less clear. Furthermore, whereas Madsen included only judgments in his study, his work also showed that the margin is mentioned most often with Article 35 on admissibility. Therefore, it seems more appropriate to study the phenomenon in both judgments and decisions as is donebelow in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Relative prevalence of margin-cases 1960–2021Footnote 62

The left-hand scale shows the percentage of margin cases compared to the yearly total of cases, while the right-hand scale indicates the number of judgments and decisions published each year. This figure includes all cases with a HUDOC entry in English.

Because of the dramatic increase in the number of cases processed by the Court, the absolute number of cases using the wording ‘margin of appreciation’ is also rising.Footnote 60 As highlighted above, however, the trend is nowhere near as clear in relative terms as much existing scholarship would have us believe, and the most frequent usage of the margin took place in the 1980s and 1990s rather than after the initiation of the Interlaken reform. When dividing the numbers between judgments and decisions, the picture is even more murky.

Figure 2.1. Differences in the development in margin-usage in judgments and decisions in the full time Court 1998-2021.

When illustrating the judgments and the decisions apart in this way it becomes obvious that while the relative use of the margin of appreciation in judgments has risen since the initiation of the new Court in 1998, the usage in decisions has fallen.

There is an indicator that the percentage of margin-mentions in judgments (but not in decisions) has been rising slightly since 2010 (Figure 2.1). The percentage of margin-cases was, however, higher ten years earlier (Figure 2), and in any year the cases mentioning the margin still account for less than 15 per cent of all cases (judgments and decisions) from the ECtHR, which is not a lot for a doctrine that could in principle be invoked in the treatment of almost any article.Footnote 61

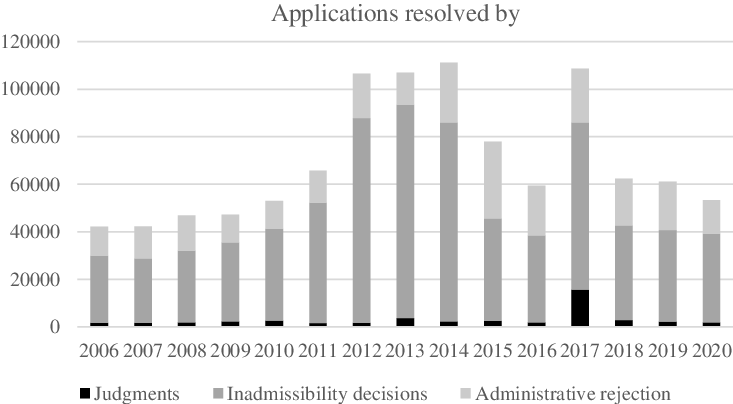

Another often neglected detail, which is relevant to include when considering these numbers, are the cases that were never made public in HUDOC and which are therefore absent from both this study and most if not all other qualitative and quantitative studies. These include the cases that are rejected before they reach a judicial formation, as well as the cases declared inadmissible by the single judge formations. The single judge formations were established by Protocol 14 in 2010 and allow for a single judge to declare applications inadmissible.Footnote 63 Most of these are rejected due to the non-exhaustion of domestic remedies or non-adherence to the six-month deadline (from August 2021: four-month deadline), but as the formation works under Article 35, a case could also be declared inadmissible for being manifestly ill-founded, treating the Court as a fourth instance, or because the applicant is deemed not to have suffered a significant disadvantage – all determinations which might well include considering the margin of appreciation.Footnote 64 As was established by Madsen in his study of cases that were made public, decisions under Article 35 did indeed often include a margin of appreciation consideration.Footnote 65 Another category of cases which are not made public is those rejected under Rule 47, which came into force with the 2014 changes to the Rules of the Court and the introduction of an online application form. This change enabled the Registry to reject cases at an earlier stage if any information or documents were missing.Footnote 66 Together these types of cases might be considered a kind of adjudicative ‘dark matter’ since it remains invisible to most scholars and political actors with opinions on the Court. The cases do exist, however, and the Court and its registry keep track of their number. Since 2006 the Court has published yearly statistical information about the number of cases dismissed administratively in addition to statistics on judgments and decisions which have been around for longer (see Figure 3). Those numbers show unequivocally that a judgment on the merits is a rare outcome for an application, but there does not appear to be a clear trend that this has changed over time.

Figure 3. Most cases are rejected or declared inadmissible (created using the Court’s official yearly statistics)Footnote 67.

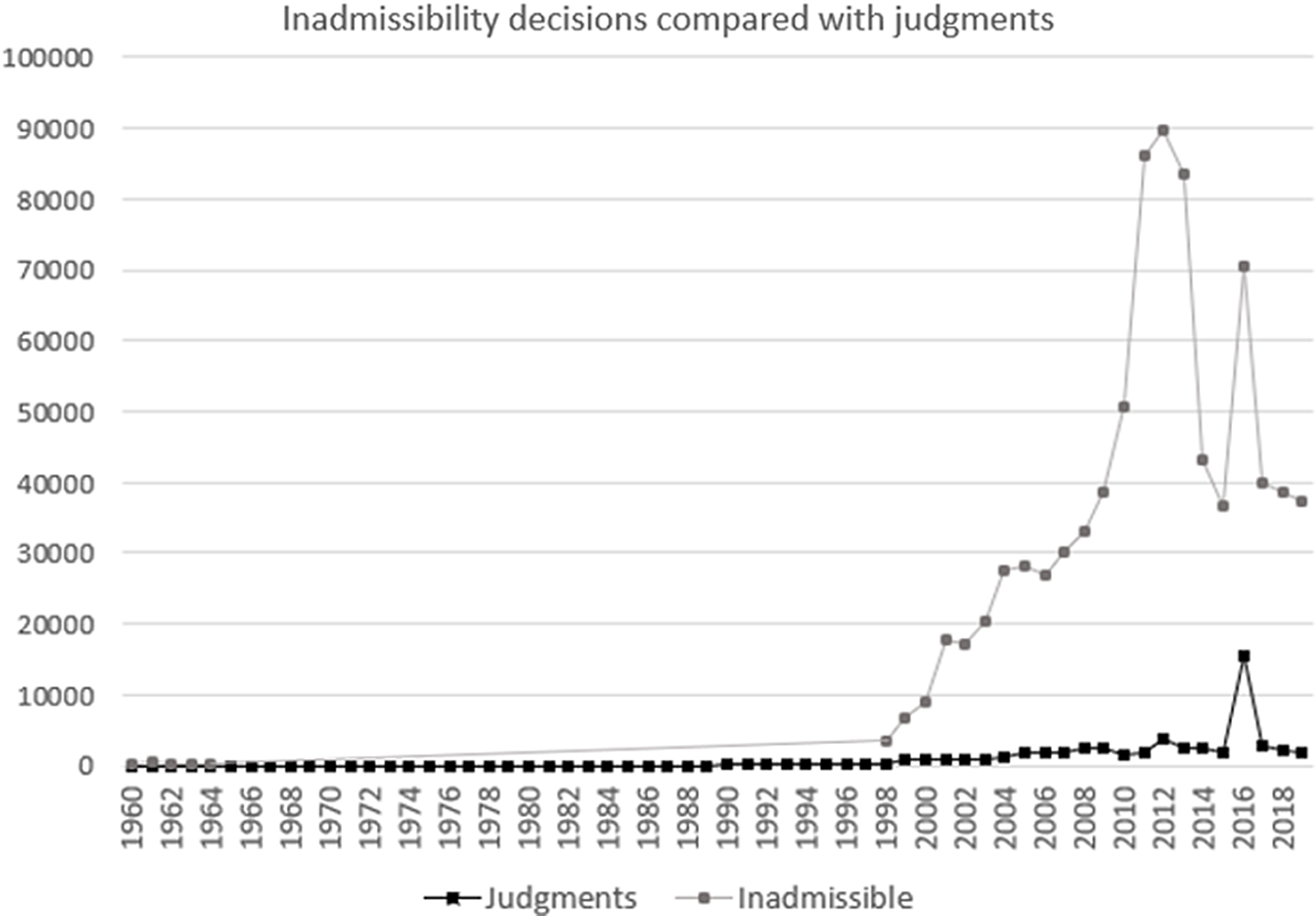

For most legal-doctrinal scholars, the non-published cases are of very little interest. They are unlikely to contain any innovative interpretations, and the Court itself does not refer to these cases in its reasoning in other cases. For practitioners and potential applicants, however, it is crucial to keep these cases in mind, as more than 90 per cent of all applications will be rejected, struck off the list or declared inadmissible for the same reasons as accorded in these cases.Footnote 67 For those interested in preserving the Court’s legitimacy, the fact that the vast majority of individuals who turn to the Court for help experience having their cases rejected with little or no explanation might also be a cause for concern.Footnote 68 For this article, the unpublished inadmissible cases are relevant when addressing claims in the literature concerning whether the Court is increasingly activist or restrained or, in other words, whether it has entered what president Spano has referred to as an ‘Age of Subsidiarity’. On the one side of this debate there are claims that the Court is expansive in its interpretations and is increasingly finding violations, whether accompanied by a critique of this or not.Footnote 69 On the other side, there are the claims that subsidiarity, judicial restraint, and state deference are on the rise.Footnote 70 Logically, it should follow that both sides cannot be right, even though there are large bodies of literature supporting both. While some of the discrepancy, especially in politically charged literature, might be explained by bias or cherry-picking on the part of the author, we can also explain the discrepancy by taking the adjudicative dark matter into account. Considering that subsidiarity concerns can play a role both in the determination of admissibility and in the substantive interpretation, an increase in the number of inadmissible cases may be as much an indicator of increased deference to states as a decrease in the number of non-violation judgments. The evidence for this argument can be seen in the two figures below. The first (Figure 4) charts the percentage of state wins over time. This figure was made by dividing the number of non-violation and inadmissibility decisions by the total number of decisions in 21,954 judgements, using the conclusions meta-data scraped from the HUDOC database;Footnote 72 it, therefore, does not include the inadmissible cases that were not made public. The second figure (Figure 4.1) shows instead the number of judgments in relation to inadmissible cases as reported in the Court’s yearly statistical reports.

Figure 4. Percentage of individual decisions in judgments resulting in a non-violation of inadmissibility result.

Figure 4.1. Numbers of inadmissibility decisions and judgments 1960–2021.

The number of cases declared inadmissible in the Court’s official statistics displays a large increase in 2010. Be aware that there are no data points between 1966 and 1998 on the number of inadmissible cases as the Court did not publish that information in those years.

While we should not overstate the importance of these data; both the specifics in interpretation, as well as the importance and general interest of a case, mean that a single violation-judgment could represent more adjudicative innovation and receive infinitely more public scrutiny than the next ten cases regardless of their outcome, it is still worth noting that where Figure 4 clearly supports the claim that the Court has become more likely over time to find violations against states, and by proxy that it is less deferential with a slight adjustment after 2012, Figure 4.1 suggests the opposite, namely that more cases are rejected before even reaching the Court, indicating greater state deference.

5. Empty mentions and the use by different actors

Section 4 aimed to nuance and explain discrepancies in existing claims that the Court is either more activist or increasingly deferential to state parties and whether it is using the margin of appreciation language more or less often over time. It also showed the limits of high abstraction level descriptive statistics on the Court’s case law, which cannot tell us whether usage of the margin of appreciation language is associated with increased deference, nor how it impacts decision-making overall. The first step in getting closer to these answers is to move down an abstraction level and determine which actors at the Court invoke the margin of appreciation language at which width (R1) and for what purpose (R2).

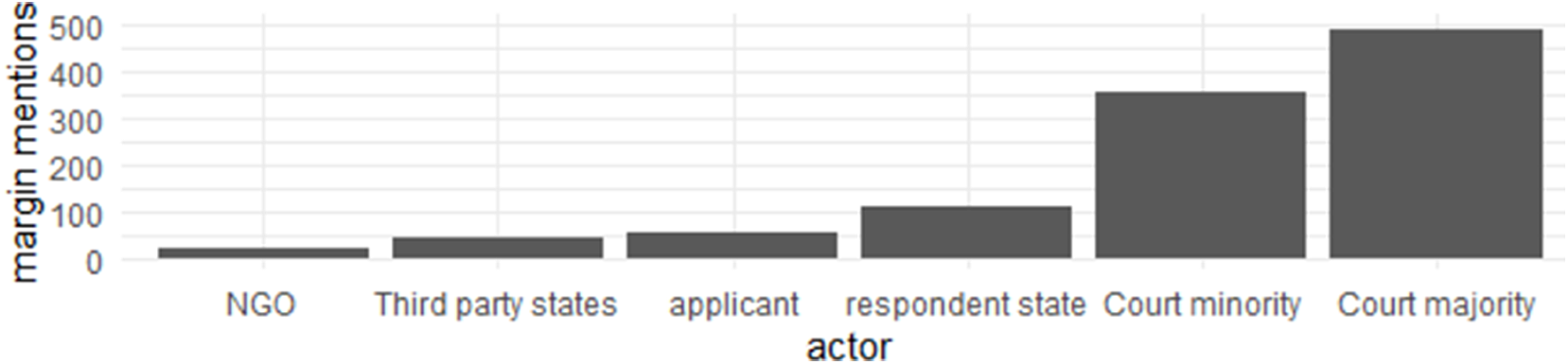

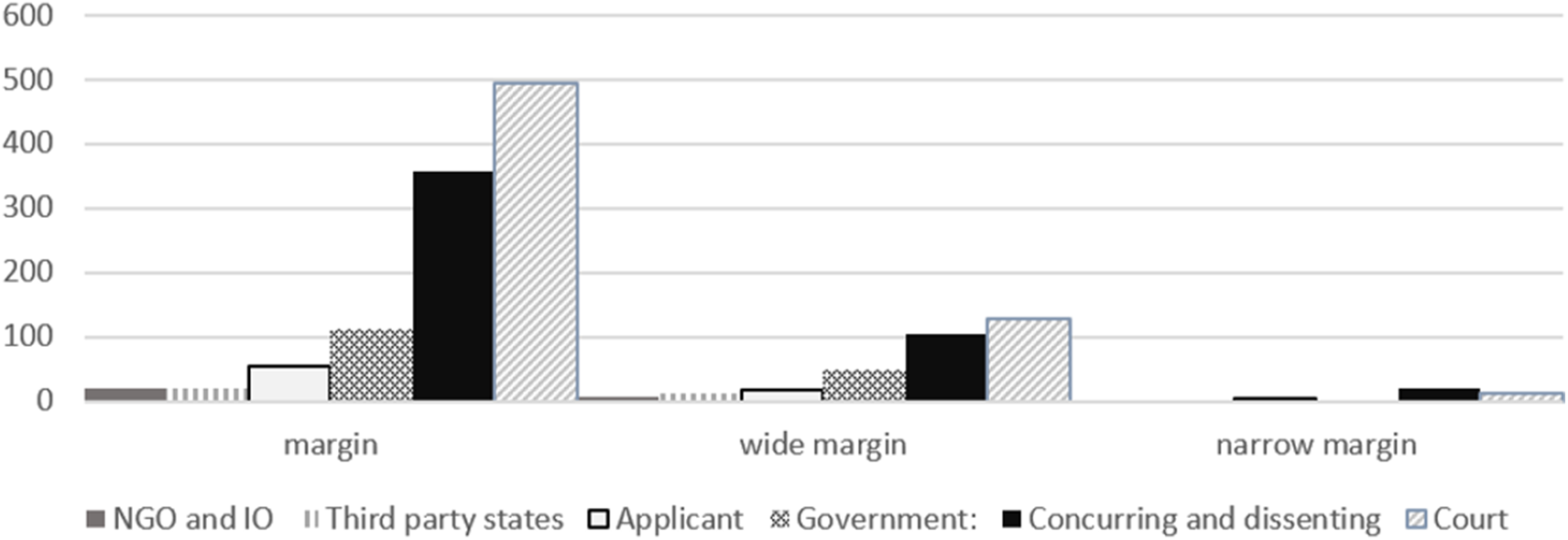

On R1, my coding of the 202 key- and level one cases showed that governments did mention the margin more often than applicants, but they were not by far the most active users of the doctrine, which were instead the Court itself, whether as majority or through judges’ separate opinions. This first result suggests that there will not be many cases in which the government has attempted to invoke the margin of appreciation, without that invocation being taken up by the Court (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Court majority most frequent user of the margin of appreciation terminology.

The figure illustrates the total number of ‘margin of appreciation’ mentions in the sample of 202 key- and level one cases divided by which actor has used the margin language.

Furthermore, the coding showed that about two-thirds of margin-mentions did not include an indicator of the width, while one-third concerned a wide- or wider margin. The number of narrow- or narrower margin mentions was minuscule, about three for every hundred mentions (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Prevalence of the use of wide and narrow to describe the margin of appreciation.

The figure illustrates the total number of ‘margin of appreciation’-mentions in the sample of 202 key- and level one cases divided by whether it was accompanied by an indicator of width and which actor has used the margin language.

This second result can be interpreted in different ways. While some authors have in some cases, lamented the tendency of the Court not to indicate the width of the margin when it invokes it,Footnote 73 other contributions, including from judges and former judges at the Court, simply treat a ‘certain’ margin as a mid-level margin.Footnote 74 Below is a bit more detail about whether some of these are empty mentions. In any case, however, the result seems to suggest that a quantitative analysis based on the margin of appreciation language should not contain many false positives where the margin-language is applied to argue in favour of a narrow margin.

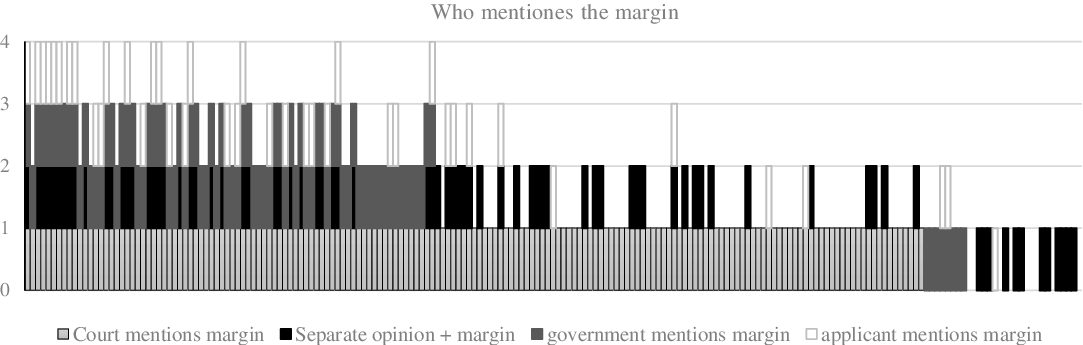

On the other hand, however, the analysis also showed that the number of margin-mentions was widely different between cases with one case sporting a full 50 uses of the marginFootnote 75 while in 55 other cases the margin was mentioned only once, and in 22 cases (11 per cent) the Court itself did not engage with the margin of appreciation or with any argument of subsidiarity (see Figure 5.2). In 13 of these cases the margin was instead used in the separate opinions of the dissenting and concurring judges, in some cases decrying that the majority has not engaged with the margin.Footnote 76 While in another eight cases the margin was used only by the government or its national courts; in two of these also by the applicant and in one only by the applicant stating that the margin was not relevant.Footnote 77 In the final case where the Court does not engage with the margin, an intervening third state was responsible.Footnote 78 These cases are the most obvious ‘empty’ instances of margin-cases where the margin-language is not followed up by an engagement with the doctrine in the determination of the majority opinion. It is not automatic, however, that cases where the Court does not use the margin are empty in this way. In an additional seven cases the Court did not use the margin of appreciation language but referred to a similar subsidiarity-based argument in another way, for example, by stating that it would not substitute its view for that of the national courts.Footnote 79

Figure 5.2. Who mentions the margin of appreciation in individual cases.

Illustration of by whom the margin was mentioned in 202 cases. In 29 cases, the Court doesn’t mention the margin directly, but in seven of these (including the four where neither court, government, applicant nor a judge in a separate opinion mentioned the margin) the Court referred to the margin using other types of language.

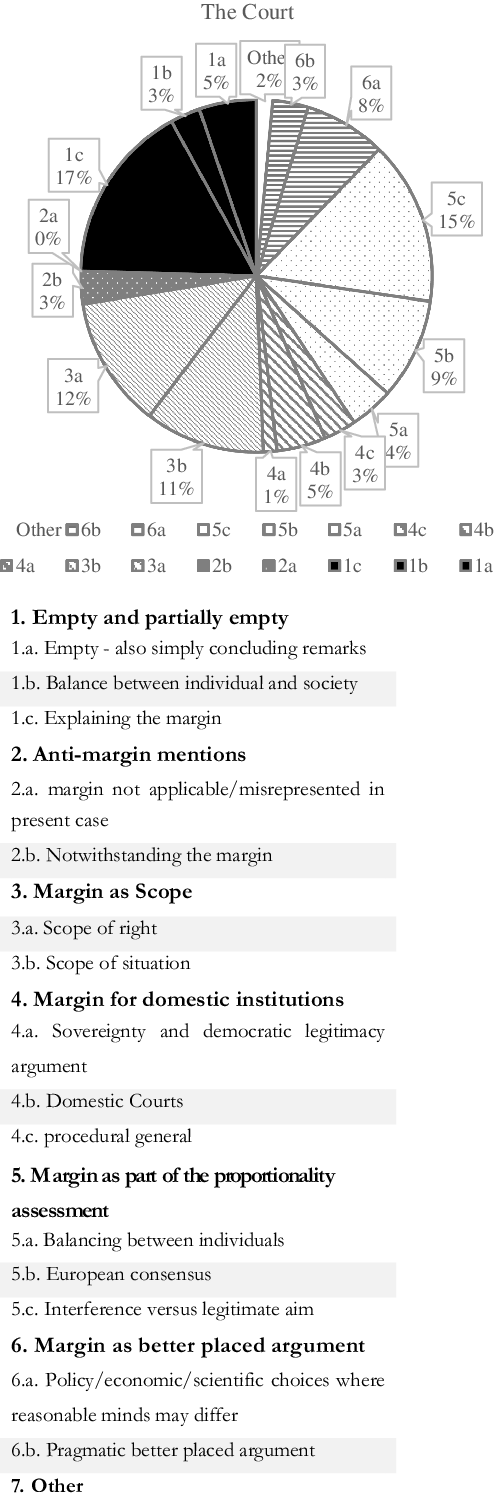

In addition to these 11 per cent of cases, there may be cases where the Court mentions the margin, but where it still has no influence on adjudication (see Figure 6). The literature on empty mentions includes as contestants for this type of cases: standardized quotes that the Court includes on its general principles of interpretation without necessarily engaging with the margin in its adjudication,Footnote 80 and where the margin is mentioned only at the very end of the Court’s considerations as a concluding note.Footnote 81 In the following, the first type of empty mention is 1.c. when the Court applies a standardized formulation to explain its interpretive tools including the margin. The second kind, here labelled 1.a., is where the margin is used as a concluding remark. The 1.b. in this coding refers to situations in which the Court mentions the margin as a principle for balancing between the individual and society but does not engage with it further.

Figure 6. Different types of margin of appreciation arguments.

The coding shows that the Court uses the margin more often than any other actor, mentioning the margin 413 times in 172 out of 202 cases. Roughly a quarter of these are standardized reiterations of how the margin works which may or may not impact the case. Another quarter connects the margin with the scope of the right or situation rather than with a proportionality argument while the remainder engages with proportionality, ‘better placed’ arguments, and procedural questions. In about half of the cases in the sample, the Court has divided its assessment into a section on general principles and a section applying those principles to the present case. Margin mentions in the sections on general principles account for about one-quarter of all margin mentions and a lot of them are simple explanations for how the margin is usually applied in connection with a particular right,Footnote 82 often directly citing definitions used in earlier cases.Footnote 83 This does not mean, however, that these are necessarily empty mentions since in three out of four cases they are followed up with a proportionalityFootnote 84 or proceduralFootnote 85 type arguments in the following section on the application in the present case. The same applies in cases where the empty margin-mention is present in the concluding remarks. Here as well it is in most cases preceded by other types of margin mentions.

In most cases the Court’s use of the margin is therefore related to balancing arguments, though there are a few examples of truly empty mentions of the margin without follow-up in legal argumentation in the sample. One of these is M.N and others v. San Marino, a case on the privacy of banking information, where the Court in its treatment of Article 8, included a standardized margin-explainer in paragraph 73 under ‘general principles’ but relied instead on an either-or analysis of exhaustion of domestic remedies as the main theme in its treatment of the present case.Footnote 86 Another is Piechowicz v. Poland, a case concerning the right to family life for a detained person. Here the Court too included a standardized explainer of the margin of appreciation in the application of Article 8,Footnote 87 but the following balancing was conducted by considering the degree of interference and potential other solutions the state could have applied rather than a complete ban on family visits, and not whether the state was well placed politically or pragmatically to make that distinction.Footnote 88 With regards to the anti-margin mentions there are no cases in the sample where the Court uses one of these without also having engaged with the margin in relation to scope, procedure or proportionality.

Altogether, there are 14 cases (7 per cent) in the sample of 202 cases where the Court has engaged with an empty margin mention without also having applied another type of margin mention, whether proportionality-based, procedural, or related to scope. These types of empty mentions with no follow-up are therefore relatively rare but put together with the 22 cases where the margin is mentioned, but not by the Court, this still leaves us with 17 per cent of margin of appreciation cases in this sample which can be characterized as ‘empty’ mentions of the margin without impact on adjudication – statistically speaking, false positives. This rate of false positives is not so high that statistical analysis is impossible, but it does place limitations on the conclusions we can draw from statistical analyses – both in this article and in analyses that have been done on this topic before.Footnote 89 Knowing the frequency of empty mentions informs the interpretation of the quantitative data – something which has been missing from quantitative analyses of the margin of appreciation until now.

6. Adjudicative consequences of invoking the margin of appreciation

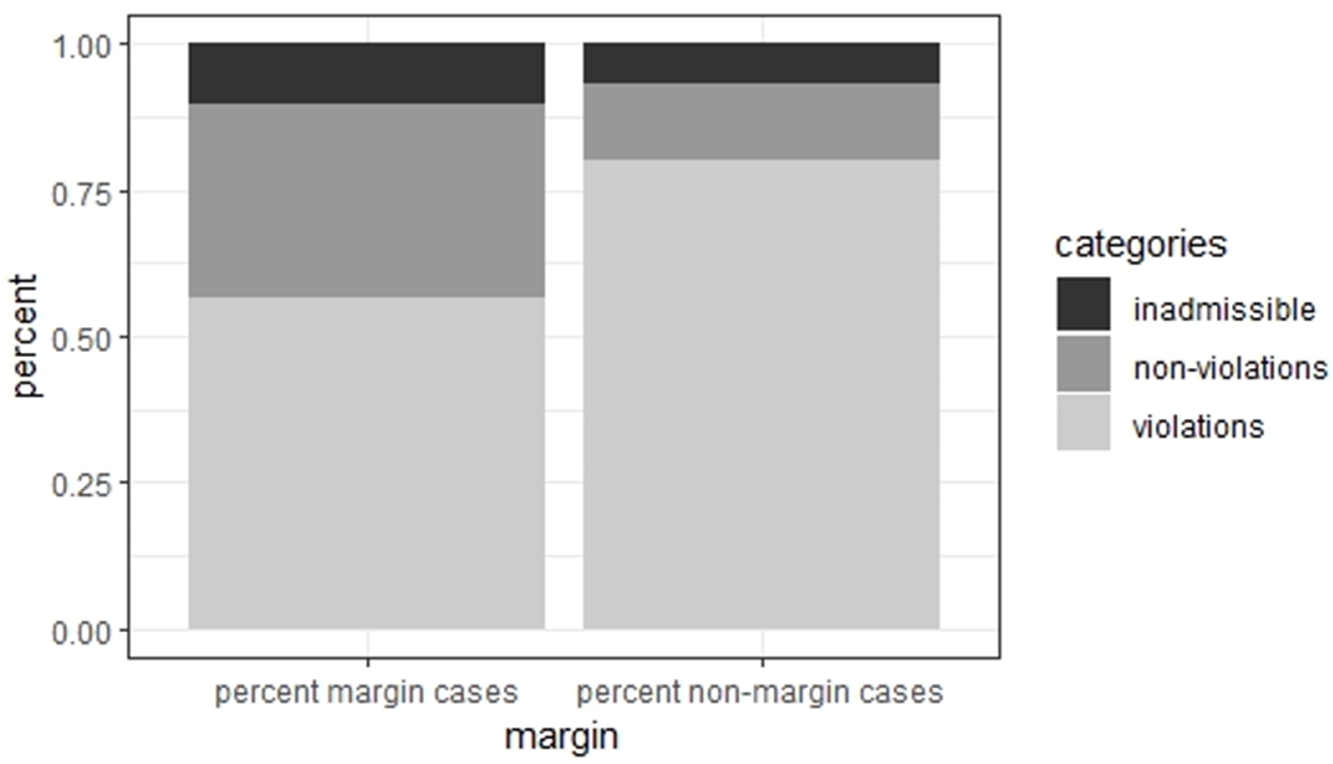

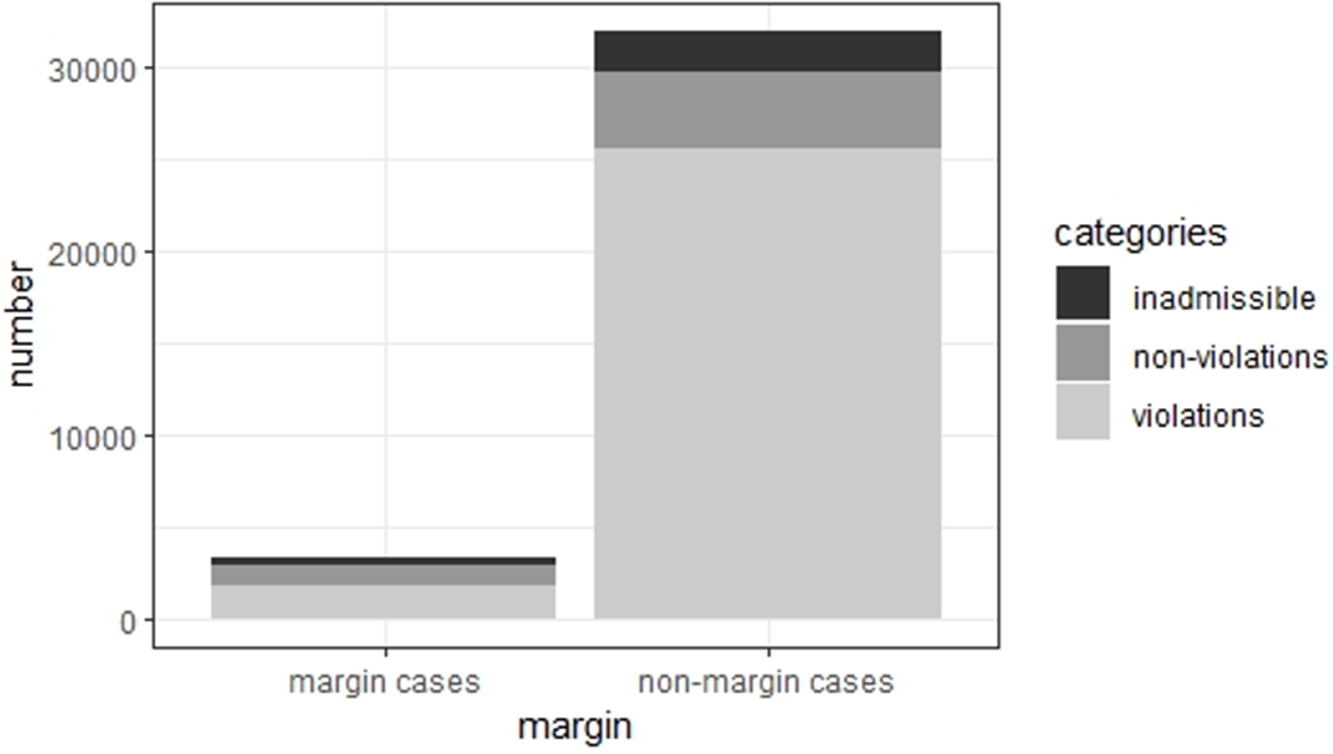

Turning to the question of whether the margin of appreciation mentions generally are connected with state deference through the proxy of state wins, let us start at the highest abstraction level with descriptive statistics on the 21,954 judgments between 1960 and 2019, the relative prevalence of the different outcomes in cases that mention the margin. At first glance, margin-cases appear quite different from cases with no mention (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Relative numbers of violation, non-violation and inadmissibility decisions in judgments with and without a mention of the margin of appreciation.

This figure was created on the basis of a dataset created by adding the distinction of ’margin of appreciation searchword’ on the basis of a HUDOC search to the Stiansen-Voeten dataset. The counts are done per decision rather than by article based on the metadata provided as ’conclusions’ meaning that a single judgment may contain several decisions, some of which result in violations, others in non-violations. In total the figure represents 35,115 decisions within 20,954 cases.

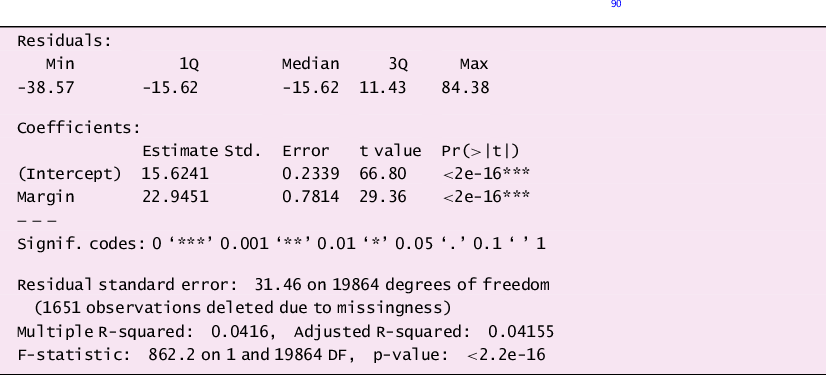

Among the cases that do not mention the margin, 80 per cent of decisions result in a violation judgment, in the margin of appreciation cases this is just 56 per cent. However, even though these results prima facie appear significantly different, we should not draw any conclusions yet. When conducting a simple regression analysis (see Table 1) on the relationship between the chance of a state winFootnote 91 and the appearance of the margin of appreciation in the case, there does not appear to be a very strong correlation. The result is significant (p-value is less than 0,001) and the estimate is in the direction that a margin-mention increases the chance of a non-violation or inadmissibility conclusion, but the model can explain only roughly four per cent of the variance (the R-squared), meaning that 96 per cent of what determines the result of a case is something else. Furthermore, taking into account that 17 per cent of margin-mentions are false positives we really cannot explain much variance at all.

Table 1. Relationship between state-wins and margin of appreciation mentions in casesFootnote 90

The explanation for this oddity is the rare usage of the margin of appreciation. Only 1,868 of our cases, representing 3,261 individual violation, non-violation, or inadmissibility decisions out of 35,115 decisions in the 21,954 cases, mention the margin of appreciation (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1. Number of violation, non-violation and inadmissibility decisions in judgments with and without a mention of the margin of appreciation.

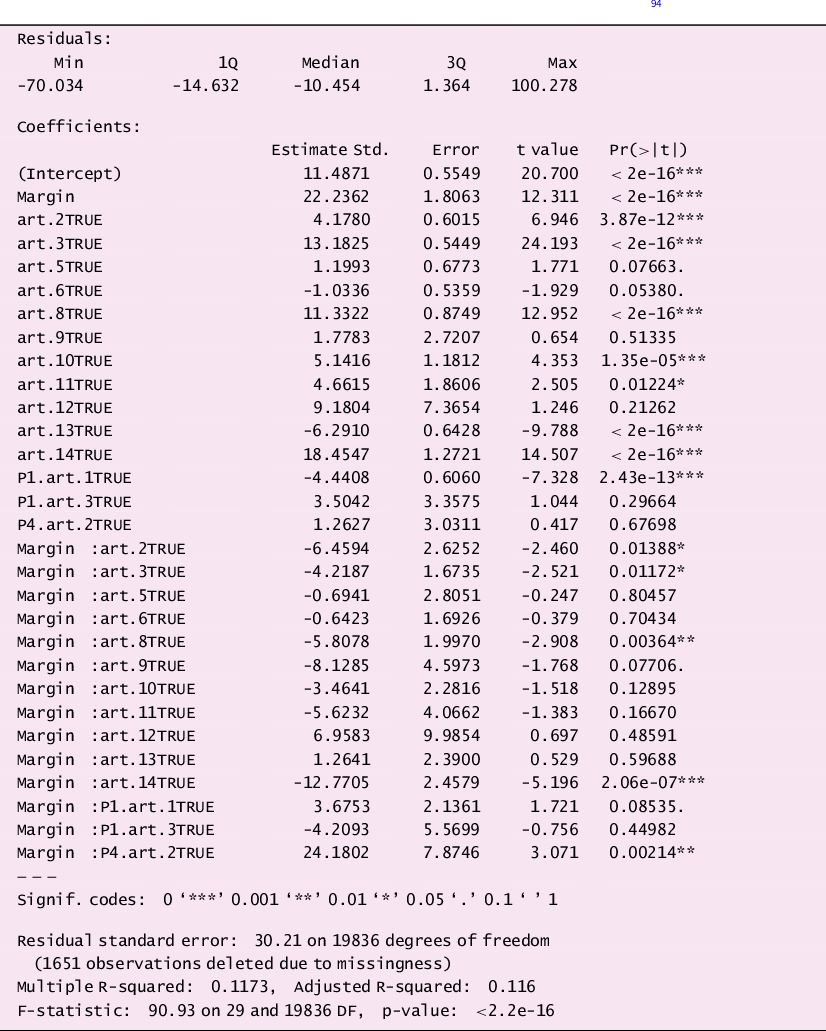

The model in Table 1 qualifies cases as ‘margin cases’ where the margin of appreciation appears at least once in the judgment rather than the cases containing the margin of appreciation keyword. This has been done since one might argue that the keywords are not the most accurate portrayal of a case, because they are allocated to fewer cases than the ones in which the phrase appears somewhere in the text.Footnote 92 Furthermore, it is not public knowledge how the HUDOC administrators determine which cases receive the keyword and which do not. Second, the model combines non-violation judgments and inadmissibility decisions into one value, ‘state wins’ since both may indicate state deference. However, still given these conditions, the analysis suggests rejecting the assumption that the use of the margin increases the chance of state wins to a significant degree. It may still be the case that while other characteristics have a greater impact on the variance in the chance of state wins, the margin still has an impact within these categories. Comprehensive works on the use of the margin of appreciation such as Arai-Takahashi and Greer contain chapters on the use of the margin in different articles because the use is different in different contexts.Footnote 93 In order to check for this possibility, this analysis presents the model in Table 2, which in addition to regressing the margin of appreciation on the percentage of state wins also checks for interactions with the 14 most commonly used Articles (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between state-wins and the margin of appreciation for different articlesFootnote 94

Several interesting connections and data points become visible through the model presented in Table 2. The first detail to notice is that with both the margin and the articles we can explain 11.6 per cent of the variation (R-squared), which although higher is still not impressive considering the high number of variables. Furthermore, several of the variables no longer yield significant results (p-values are too high). This is not in itself surprising since including the articles slices the data set into many smaller sets each with a smaller chance of yielding significant results. The second result of interest is that when the regression checks for interactions between the margin and the individual articles, in several cases the chance of a state win appears to decrease rather than increase. This is the case for Articles 2, 3, 8 and 14 (see Table 2). Considering that the margin in general is associated with a greater chance of a state win, this is a surprising result. There is no obvious theoretical explanation for why these articles should be different from other articles adjudicated at the Court. In fact, Article 8 is among the list of articles where the Member States in the Copenhagen Declaration welcomed the strict and consistent application of the margin of appreciation.Footnote 95

As a result, the study must conclude that statistically there is no clear relationship between the mention of the margin and a state win. Member states pouring a lot of energy into, and potentially overstepping the independence of the Court in order to make the Court use the margin more, may be disappointed to learn that it does not significantly improve their chances of winning cases.

Turning then to the hypothesis in this article that the hidden variable that ties the margin of appreciation language to the adjudicative results, might be the degree to which a case can be considered hard, in terms of complexity, novelty, and importance. Implicitly if this hypothesis should be able to help explain the discrepancy in Figure 7, then hard cases should be more likely to result in state wins than less complex cases. As explained briefly in Section 4, the reason why this might be the case can be found in the practice of declaring applications admissible/inadmissible before considering the merits. If a case is similar to well-established case law, and is unlikely to result in a violation judgment, it will be declared inadmissible and therefore rarely be published in HUDOC.Footnote 96 If, conversely, the established case law suggest that it is likely to result in a violation judgment, a violation will most often be found by a Committee of three judges, or, before the entrance into force of Protocol 14, by a Chamber, and in both cases be labelled as an importance level three case. Therefore, more low-importance level judgments result in violation-judgements. If, however, a case deals with a problem the Court has not encountered before, or if case law on the topic is contested, there is no clear tendency that the case will resolve in one direction or the other; rather, it will be dealt with by a Chamber or the Grand Chamber with a more equal chance of a violation or non-violation judgment.

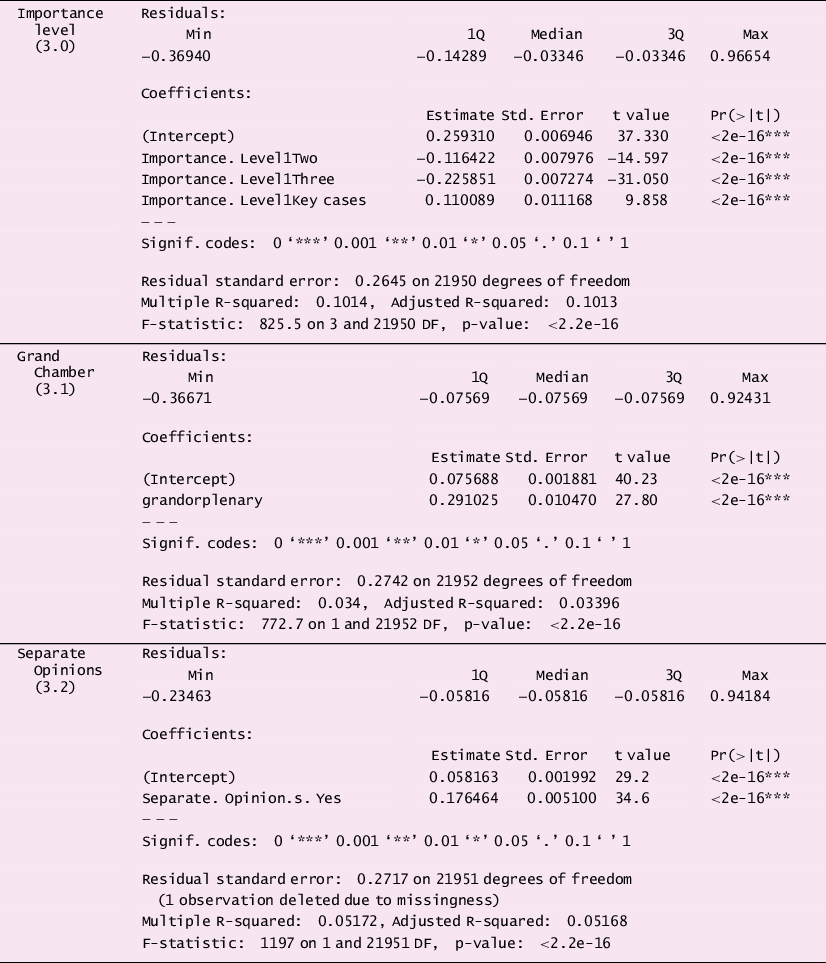

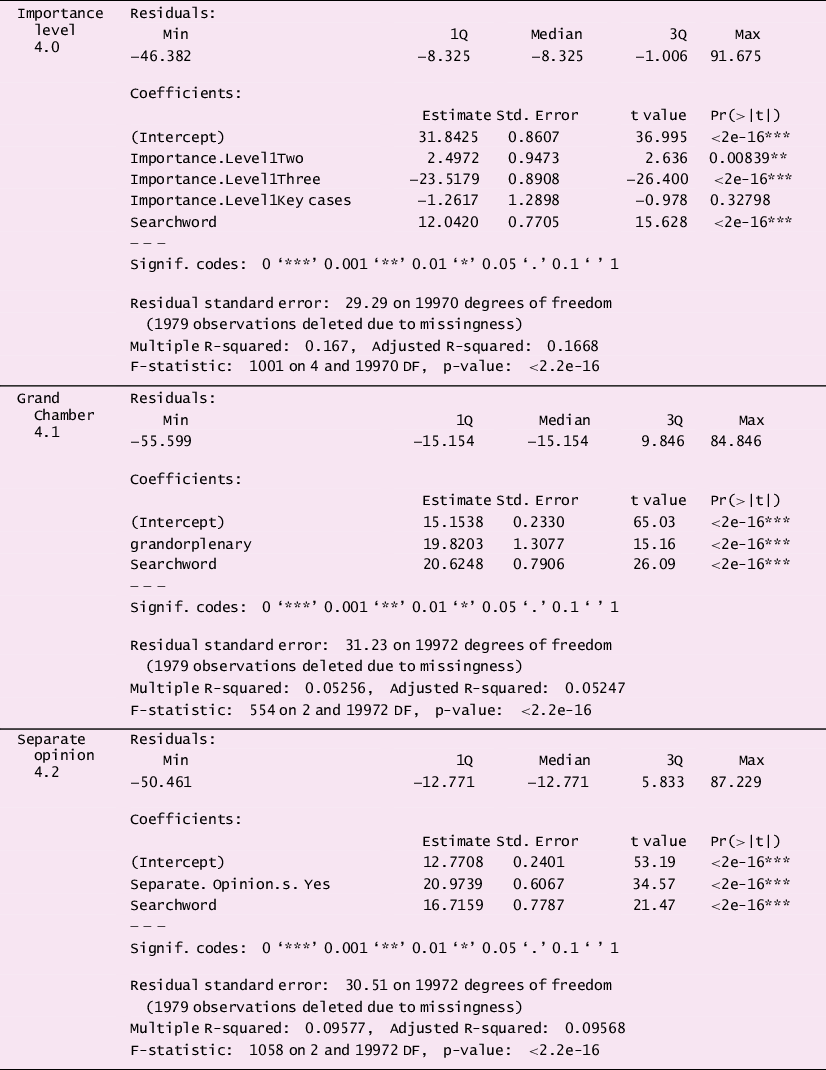

The most important proxy for ‘hard case’ is, therefore, the ‘Importance Level’ assigned by the Bureau. Other indicators of the hardness of a case may also be whether a case has been heard by the Grand Chamber (or previously, the Plenary Court). The Grand Chamber adds complexity initially because there are simply more voices in the analysis when more judges are considering the case. Furthermore, a case only makes it to the Grand Chamber if there is or it is predicted that there will be disagreement about the case in the Chamber, suggesting that the Grand Chamber cases are more likely to be hard cases. Another is whether any separate opinions have been issued to the case, the cases carrying a separate opinion are similarly assumed to be cases with no straightforward answer resulting in enough disagreement on the bench that at least one judge felt the need to either dissent or clarify their concurrence. As mentioned in the introduction these indicators are somewhat colinear, in that all Grand Chamber cases are key- or level one, but many key- and level one cases are not Grand Chamber cases. Furthermore, very few level three cases contain any separate opinions. Due to the co-linearity, we cannot simply add these variables to one multiple regression table, but we can have a look at them individually (see Table 3).

Table 3. Models showing the relationship between the prevalence of margin of appreciation language and three indicators of hard case

In each case, the result points in the direction assumed by the hypothesis, namely that higher level cases, Grand Chamber, and cases containing a separate opinion are more likely than other cases to include a margin of appreciation mention. The R-squared remains quite low, with importance level explaining 10 per cent of the variation as the highest. This is still a more robust connection than between the margin and state wins given the lower number of variables.

Testing this indirectly as well, by attempting to predict the likelihood of state wins with whether a case is a hard one, we see that the margin of appreciation has a similar effect to the other complexity variables for predicting state wins (see Table 4). It becomes obvious that ‘hard cases’ is a better predictor of state wins than the margin was on its own.

Table 4. Models showing the relationship between state-wins and three indicators of hard cases when interacting with the margin of appreciation

Models one through four together show that the relationship between the usage of the margin and the chance of state wins is not straightforward and that there is a better case for claiming that the margin of appreciation is one of several indicators of ‘hard cases’ at the Court. Furthermore, in line with theories on incrementalism,Footnote 97 and because of how the Court works in terms of declaring most cases inadmissible, hard cases are associated with greater levels of non-violation judgments than other cases. To this end, the rise in inadmissible cases may be a greater indicator that the Court has become more deferential to states than anything happening in published cases. Unfortunately, this practice along with the non-publication of most inadmissibility cases, means that there is less transparency regarding how, when, and where this increased deference is applied, and which kinds of cases are most likely to be impacted by it.

7. Conclusions

This article engaged in a systematic quantitative and mixed methods study to test the relationship between the usage of the margin of appreciation and deference to states. It concludes by substantiating what several qualitative studies have already hinted at; there is no direct relationship between the two, but there is an indirect one in the sense that the margin of appreciation is more likely to be used in ‘hard cases’ where there is no obvious solution because there is no settled case law. And these types of cases, because of the Court’s incremental approach and practice for declaring cases inadmissible, are also more likely to result in non-violation judgments.

Previous studies focused on the Court’s usage of the margin of appreciation have suggested that the reason why the margin does not grant state wins may be a complex or even chaotic usage on the part of the Court. Suggestions include that this may be because it has several different usages,Footnote 98 or because it is ‘as slippery and elusive as an eel’,Footnote 99 an ‘empty rhetorical devise’,Footnote 100 or ‘a convenient way to dispose of cases’.Footnote 101 This study has made no attempt at determining which of these is closest to the truth, though through a qualitative coding it has established the relative prevalence of several of the different kinds of usage identified by previous research. The aim of the article, rather than engaging with the question of what the margin is, was instead to contextualize political and academic debates about the topic with descriptive statistics and to test the validity of the foundational political assumption that the margin results in more state wins. Through this work the study needed to evaluate the frequency of so-called ‘empty’ uses of the margin. The coding established that although the Court invoked the margin of appreciation far more often than governments, applicants, or third-party interveners, 11 per cent of cases with a margin of appreciation mention, did not have the Court itself engaging with the doctrine, only other actors, most frequently judges writing separate opinions. And in an additional 7 per cent of cases the Court mentioned the margin only in ways that did not engage with adjudication.

The article also engaged with the more general question of whether the Court has entered an Age of Subsidiarity in which it is more deferential to states including whether the Court mentions the margin more over time. Regarding these questions, the study found that the usage of the margin of appreciation language relative to the number of judgments and decisions peaked in the 1980s and 1990s, and not with the Interlaken process from 2010 onwards. Furthermore, it found that while the claim that the Court has become more likely to find violations against states since the late 1990sFootnote 102 can be replicated statistically; in order to discover the full picture those numbers have to be held together with the increase in the number of inadmissibility decisions which are not published in the HUDOC database; in this article labelled ‘adjudicative dark matter’. Future research aiming to discover whether the Court has entered an ‘Age of Subsidiarity’ with the Interlaken reform process may be better off investigating how the practice of declaring cases incomplete or inadmissible has changed over time rather than tracking margin of appreciation usage, which does not appear to correlate with deference.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156522000565.