1. Introduction

States can play multiple roles vis-à-vis change in international human rights law: They can be drivers and nurture the narrative of a truly universal order when concluding treaty negotiations, or ratifying additional protocols enabling individuals to file complaints against them, they can block these processes and advance their own rather than the common interests, and they can also actively push against further development of human rights. These characterizations together point us towards the conventional thesis on change in international human rights law – that it depends on the central hand of state actors. While this claim is not without empirical merit, with states’ power to drive or block change processes widely undisputed, this article highlights that states rather assume a broader spectrum of roles in affecting legal change at the international level than solely that of the be-all, end-all orchestrator. Some are intermediate, e.g., when states act as catalysts or spoilers. And others are more inert, where states either do not act at all or take roles at the margins, becoming bystanders to international legal change processes driven by other actors.Footnote 1

This article focuses its analysis on these latter roles and, particularly, on the impact state bystanding has on international human rights law. By way of this analysis, this article argues that international legal change in human rights benefits from a states-as-bystanders effect. This effect refers to social psychological theory which assumes individuals to be less likely to offer help when other people are present and has been transferred to non-emergency social situations.Footnote 2 This assumption transfers well to the human rights regime, where state inaction is encouraged by the multitude of actors at all levels who seek to support individuals through demanding justice and bringing human rights claims into agendas. Indeed, this phenomenon often shows in the crises preceding such processes, where states, confronted with a human rights situation that threatens greater harm without their response, initially choose not to act amidst a number of other involved organizations and individuals.

The article contributes an explanation for change in international human rights law that goes beyond dominant explanations of state-led change. I develop the argument that advocates for change will turn to alternative paths,Footnote 3 like the expert or multilateral institution path, if (the majority of) states do not act for change but remain bystanders. This article bears its core argument by developing an analytical framework and illustrating its utility in an in-depth case study of norm change.Footnote 4 I trace a change process from a norm being non-existent in international human rights law, to a non-right, to a condition for other rights and co-dependent rights and finally, to recognition as independent rights at the international level: The human rights to water and sanitation. Using evidence from original and secondary data, I show that this legal change process was driven by a coalition of independent experts and economic and social rights advocates after states retreated to the sidelines of this process. As a consequence of this state-as-bystanders effect, the coalition provided the normative framework allowing for the norm’s eventual codification through General Comment No. 15 on the Right to Water, an interpretation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).Footnote 5 With its November 2002 adoption, this Comment provided an authoritative base upon which individuals and communities could more effectively advocate for the fulfilment of their right to water – and in doing so, closed a significant gap in human rights law.Footnote 6 With this framework and the political backlash it created,Footnote 7 actors on other paths were equipped to walk, until a human right contested by states became a General Assembly (GA) Resolution recognizing a right to water and a right to sanitation only eight years later.Footnote 8 As such, states emerged from a role as bystanders to legal change to appraising the change attempts made by others. After some attempts by would-be-spoilers, most states later acted as catalysts.

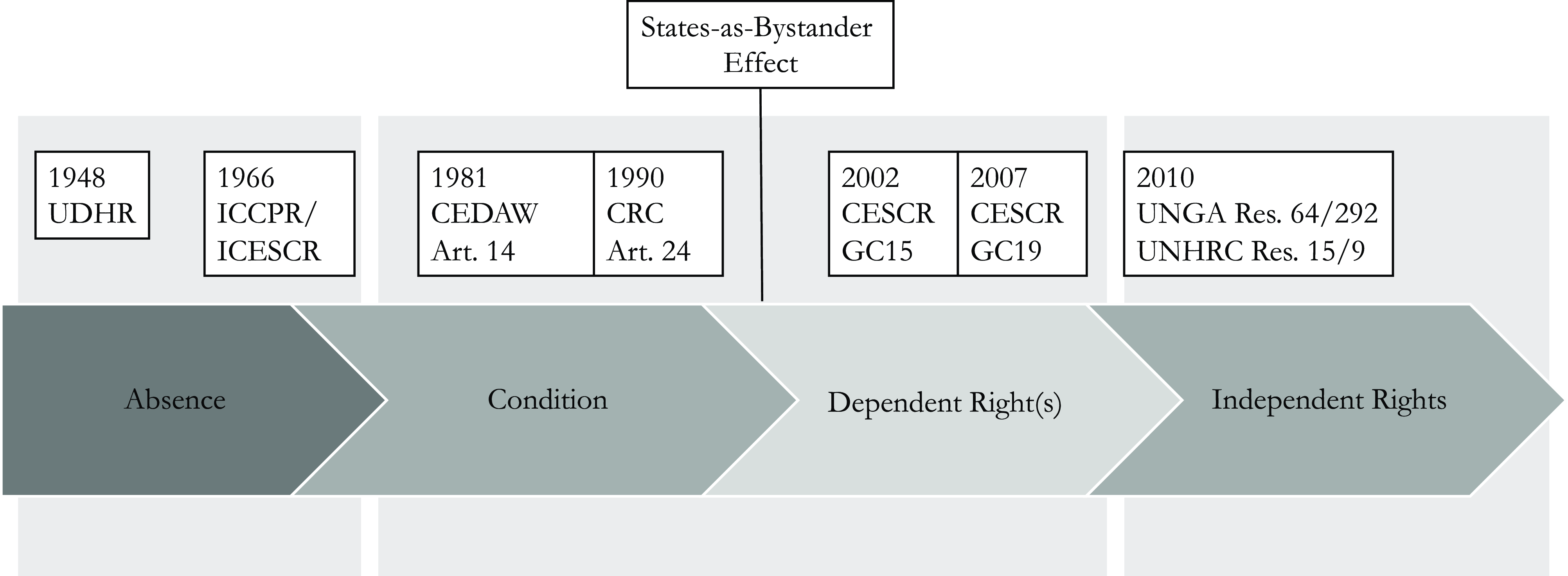

This article is structured as follows: After briefly establishing the argument that a states-as-bystanders effect offers a valuable explanation for legal change within the literature on human rights norm change, I proceed to lay out my analytical framework. Based on a timeline when water was considered a human right at the international level, I submit four distinct phases as segregating the norm development in question since the United Nations’ (UN) founding. First is the ‘no right’ phase, from 1948–1981, in which water issues played no role in human rights law. The second begins with the entering into force of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)Footnote 9 in 1981 and is labelled the ‘conditions’ phase, when water was mentioned in human rights treaties as a condition for the enjoyment of rights for distinct groups. In what continues until 2007, and is marked by the attachment of water, and later sanitation, to other rights through interpretation; we may deem this the ‘co-dependent right(s)’ phase. In the final phase, water and sanitation became formally recognized as independent human rights. These delineated phases structure my subsequent actor-centred analysis of the politics behind this change process. After discussion of the states-as-bystanders effect in human rights law, the article concludes with my analysis’s implications for human rights practice and scholarship and the state’s role in international legal change more broadly.

2. Human rights and norm change

Although the field of human rights shows no dearth of sophisticated theoretical models for highlighting norm change through non-state actors, these models remain state-centric. The boomerang pattern and the spiral models,Footnote 10 as well as the justice cascade,Footnote 11 all theorize influential non-state actions to bring about human rights change vis-à-vis the state and ultimately through governments. This state-centrism owes itself largely to the models’ approach of norm change as change in commitment or compliance with human rights, thus when a norm already exists as a right but is not yet (fully) implemented. A focus on legal norms overlooks a multitude of social norms which shape behaviour at all levels without being legalized in international law.Footnote 12 A more refined perspective on norm emergence in international relations accounting for different stages and actors of a norm, as well as their intersubjective construction, were recently introduced to the discipline,Footnote 13 but without fully taking into account the specifics of legal norm change. International legal change processes, on the other hand, are interested in why some norms are still yet to be codified as independent rights into human rights law, and how co-dependent rights finally became independent human rights. Analytical inquiries usually reveal states interests and power dynamics as creators and blockers of international law, but may also point to other pathways for legal change.

Within these other alternative pathways, the international law literature has emphasized the sizeable role formal institutions, such as international and domestic courts, potentially play as change agents.Footnote 14 Research on this front has clarified the extent to which international courts’ judgments can change domestic policies beyond case parties,Footnote 15 as well as shown how the design of these institutions constraints judicial practicesFootnote 16 and how, despite these constraints, judicial activities can invoke incremental norm changeFootnote 17 . Further research into the intra- and inter-organizational dynamics of these institutions and actors has brought greater nuance to our understanding of their legal agency. Well-documented, for example, is non-governmental organizations’ (NGOs) indispensability to the operations of courts,Footnote 18 the effect of shaming and faming on reforms,Footnote 19 while another line of research – into the mediating role of regulatory intermediaries – has offered a theoretical account of (indirect) rule-making by third parties.Footnote 20

Several motives base the interest of non-state actors, especially those claiming to represent civil society, in the making of international human rights law. In general, domestic and transnational advocacy groups and networks need the international legal framework to hold governments accountable.Footnote 21 Human rights defenders and lawyers use strategic litigation,Footnote 22 both through national and regional courts but also through individual complaints at the treaty bodies, to get clarification of what constitutes a human right violation, and can point to international human rights law when domestic law is ambiguous or silent about a violation. This clarity rendered tangible is moreover crucial for awareness-raising: as grassroots or local actors need people to know that a certain government behaviour is unlawful and that they have rights to defend themselves, international human rights law may be cast as an instrument to overcome injustice,Footnote 23 speak ‘rights to power’Footnote 24 and empower individuals in international politics.Footnote 25 While this assumption deserves critical examination with regard to just representation, civil society actors’ interest in the change of human rights law and the long-standing success of NGOs and transnational advocacy networks in bringing domestic policy change highlights their role as potential change agents in international law.

Paths other than state-led ones are likely to emerge when alternative authorities exist in a given context – authorities that, similar to courts, international bureaucracies and public or private expert bodies, are recognized as having significant weight in the ascertainment of international law, even if they do not enjoy acceptance as formal law-makers.Footnote 26 The UN human rights treaty bodies are widely regarded as authorities for the monitoring of human rights law,Footnote 27 best described as state-empowered entities.Footnote 28 Actors who want to see change enacted are likely to turn to such authorities when state-led paths are blocked.Footnote 29 The activation of such alternative authorities does not necessarily leave the remaining states out, but they need to react, individually or collectively, in order to regain influence on the process. Such reactions are rendered more difficult when states are divided on the issue. The extent of such alternative paths’ centrality in change processes likely depends on the involved non-state actors’ or expert body’s recognition in a given field and the space left to them by states to act, as well as on the range of other factors facilitating access to and influence of different authorities.

I suggest that legal change in human rights may arise as a consequence of the marginal roles of states-as-bystanders. To illustrate my argument, I will trace the process of a specific case of norm change through alternative paths in international human rights law. A transnational coalitionFootnote 30 between expert body members, human rights advocates and issue professionalsFootnote 31 emerged that was decisive in bringing about change in human rights law through treaty interpretationFootnote 32 by an expert body on the issue of the human rights to water and sanitation.Footnote 33

3. Analytical framework

To outset my tracing of the legal development of the rights to water and sanitation, I begin by sketching the initial phase of development – that is, how a right came to emerge and develop at the international level. Figure 1 reflects the norm development process and structures the analysis regarding the different norm development phases. The milestones in Figure 1 are based on the formal appearance of water and/or sanitation in human right law in the UN.Footnote 34 This will set the framing for my subsequent analysis of the process, meaning an in-depth study of the pathways that were activated, not considered, or left throughout the change process in relation to the position of states.

Figure 1. Water and Sanitation in Human Rights Law.

The change process narrative begins with water’s certain absence from the UN’s foundational texts on human rights. This absence was three-fold, beginning first with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948, whose 30 articles neither included water as a right nor mentioned it in relation to any of the rights. The two Covenants adopted in 1966 to complete the International Bill of Rights alongside the UDHR – the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the ICESCR – likewise omit any reference to water. As such, the years bookended by these texts’ adoption marks water’s ‘absence’ phase.

In 1981, CEDAW became the first international human rights treaty to include water in its treaty text. Here, CEDAW’s Article 14 clarified water supply as an aspect of adequate living conditions, thus not as a right in its own regard but now at least as a codified feature extended to a particular part of the global citizenry, i.e., rural women. In 1990, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) identified clean drinking water as necessary for children’s right to health (Article 24.2(c)). These developments, which established water supply and quality as essential to the fulfilment of other already-codified human rights (adequate living conditions and health), frame the beginning threads of a new phase, the ‘conditions’ for some groups for the enjoyment of other rights phase, whereby water came to occupy tangible space in international human rights law, albeit it in the limited contexts of rural women and children.

CESCR’s adoption of General Comment No. 15 brings us to the third phase, the time at which water became formally recognized as a human right. Here, CESCR interpreted and thus attached water as a co-right necessary to the fulfilment of the rights to an adequate standard of living and to health but did not formally include sanitation as a human right or a condition for the fulfilment of rights like water. CESCR’s omission was countervailed five years later, when the right to sanitation was included alongside water in General Comment No. 19, on the right to social security.

It was only three years later that the rights to water and sanitation were finally recognized as independent rights by UN member states in GA Resolution 64/292 and the Human Rights Council in Resolution 15/9, presenting the final phase of legal change in human rights from no right to claims to dependent to independent human right for the analysis.Footnote 35

4. Analysing international human rights legal change: The rights to water and sanitation

4.1 The absence of rights

There is no right to water recognized in the UDHR – neither as a right in its own regard nor as a condition for other rights. What explains water’s absence in a document where food, clothing, and housing were each recognized as needed for the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of oneself and one’s own family?Footnote 36 Despite the well-written history of the UDHR’s and the two Covenants’ drafting,Footnote 37 there exist different narratives speaking to the reasons specific claims made it into the Declaration as distinct rights. Regarding water, these sources mainly remain silent on the subject of motive. In general, scholars see the Declaration’s drafters as assuming water to be ‘implicitly included’Footnote 38 in the components of the right to an adequate standard of living, comparable to the implicit inclusion of air. Against this view of water as a human right arising out of changed realities, Inga Winkler notes that ‘the need for access to water has little to do with changing living standards and circumstances’ but that ‘threats to access to water only now become more obvious or are only now understood’.Footnote 39 Jochen von Bernstorff described later attempts to ‘create a new right without an explicit textual basis in the Declaration’ as ‘counter-hegemonic strategy’.Footnote 40 This reference to a potential power asymmetry between actors advocating for the right to water and the absence of the right in the UDHR gained further ground with the omission of water in the Covenants presented in 1966. Food, housing and clothing were included, so was the absence of water in ICESCR the result of intention or simply, ‘absence of mind’?Footnote 41 Thielbörger reiterates the difficulty of giving empirical flesh to either result, in pointing to the limited expression of the drafter’s will in the travaux préparatoires, which show ‘the right to water was briefly considered, but eventually not included’.Footnote 42 No further discussion offers explanation of this decision; nor, hence Thielbörger’s observation, are sources available that would buttress any argument claiming either pathway of motive. Behind the scenes, the United States (US) government was working hard to keep socioeconomic rights from featuring in binding conventions.Footnote 43 As states were still the central shapers of human rights law, given their capacity as drafters and adopters of the UDHR and the two Covenants at a time when no alternative authority (e.g., treaty bodies) was present, their silence on water as a human right literally left room for interpretation.

On the multilateral path, the UN provided various avenues to address the issue of water in the 1970s. In 1977, the same year the ICESCR entered into force, the UN Water Conference produced the Mar del Plata Declaration, which, in its explicit reference to the right to drinking water,Footnote 44 provided first steps for the right’s eventual codification into an international legal norm. It is important to note here that this conference and water becoming a central issue in the 1970s and 1980s, were the result of debates and activities taking place in international environmental law. The UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm, identified water as a natural resource in need of protection and the Mar del Plata conference followed up on this discussion. Many other conferences and summits followed, producing (non-binding) action plans and declarations.Footnote 45 1981–1990 was then announced as The International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade by a GA Resolution.Footnote 46 The aim of the Resolution was to ‘bring about a substantial improvement in the standards and levels of services in drinking water supply and sanitation by the year 1990’. The UN and its agencies, like the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Development Programme, implemented ambitious programs to meet this aim, but ‘mainly as a result of population growth there were globally more people unserved with adequate water and sanitation by the end of the decade, than there had been at the start’.Footnote 47 Yet, the UN member states turned to non-binding declarations for their recognition of the right to water. Opportunities to recognize the right for everyone in hard law were missed during the parallel human rights treaty drafting processes, as the next section shows.

4.2 Water as a condition for some people’s rights

The beginning of the decade likewise marked the UN human rights system’s first substantive movement on water, as CEDAW, entering into force in 1981, the first international human rights treaty to explicitly include ‘water’ in its treaty text. Here, water supply was attached to the enjoyment of living conditions for rural women among other features,Footnote 48 meaning its access was codified at the same time its scope was constrained: it was neither a right in its own regard nor was its provision universal, extended to all women. The decade’s end saw the adoption of the CRC, which acknowledged clean drinking water as a condition, but not a right, for the fulfilment of a right to health and in relation to combatting disease and malnutrition for children.Footnote 49 The Working Group on this draft was led by delegates from Australia, Mexico, Philippines, and Venezuela, with the latter proposing the draft that included water.Footnote 50

While some states took incremental change as the best pathway to motivate recognition of a human right to water, the legal change process remained incredibly slow to react to the social challenges arising from water shortage and pollution; indeed, access to water remained a provision restricted to specific groups up until 1990. Eventually there was movement towards change, made largely on the heels of the shift of the development paradigm during the 1980s and 1990s, whereby ‘water for all’ was no longer regarded a public obligation only.Footnote 51 Supported by bilateral development co-operation and the programs and policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, this new perspective became visible in the Dublin Principles – the codified result of an 1992 expert meeting regarding global water-related issues – in which water was deemed with economic value, something to be advocated for as a commodity.Footnote 52

This emphasis on water’s economic dimensions, rather than its status as a human right, spurred heated debates at the international level, propped by NGOs from different fields, who coalesced to advocate a dissenting angle. Heading this network of NGOs were primarily those working in the field of humanitarian aid and in developing countries, though further support came from specialized agencies of the UN, like the WHO and Food and Agriculture Organization. Their activism targeted the water commodification policies of the World Bank and, more broadly, the argument around the efficiency of privatizing water supply.Footnote 53 Public-private-partnerships in this sector attracted substantial interest of companies, because risks could remain with the government and profits were high. The network lobbying for a human right to water was concerned that the scarcity of water in many regions in the world would lead to an increase of its value. Companies might take advantage and demand new terms for their public-private-partnerships, so the risk of cutting the water supply as a means of pressure was high. Advocates feared the right to water would be subject to affordability. The network supporting a human right to water framed water as a basic need instead of as a commodity. They raised awareness that water should be acknowledged as an international human right, in order to effectively advocate for water policies at the domestic and international level.

The Mar del Plata conference and the Decade as multilateral paths developed in close entanglement with and were often preceded by the NGO path to legal change.Footnote 54 NGOs specialized in agenda-setting, mainly focused on development-related aspects of water during that time. While the developed world took clean water as a matter of course, more than one billion people in the Global South lacked access to this resource. This was regarded as ‘one of the most fundamental failures of 20th century development’.Footnote 55 Development co-operation NGOs demonstrated how their work in health, agriculture and nutrition was hindered or even at risk of becoming void by a lack of access to water. Their grassroots experience facilitated calls for state action on the international level. Other international conferences followed, like the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio in 1992 and Habitat II in Istanbul in 1996, which crystallized consensus regarding the centrality of global access to drinking water and extended the scope of a potential right to water to include water for sanitation.

In short, numerous events in the field of development and environment politics confirmed international consensus on the need for clean drinking water for everyone, yet some states and international organizations favoured commodification and marketization of waters, while others emphasized water as a public good. While states were planting the seeds for change in the 1970s, their commitment to achieving universal access to water by 1990 was not only prolonged to 2000, they also reformulated water as a human need rather than a human right in the Millennium Development Goals.Footnote 56 This disagreement is important for understanding the space left for other paths of legal change. The multilateral events and meetings facilitated the establishment of transnational advocacy networks in the 1980s and 1990s,Footnote 57 comprised of actors from civil society, who organized to advocate for water issues in the field of development and environment.Footnote 58 Despite their efforts, a human right to water remained without acknowledgement by any organ of the UN into the millennium. Needless to say, not all new or changed political and social realities require norm change in international law. In order for change in international law to happen, these challenges must take place both in substance and with a long-lasting effect on global co-operation.Footnote 59 The key role to detect and frame these kind of challenges for the field of human rights often lies with transnational advocacy networks.Footnote 60 They possess key local knowledge – about implementation problems, knowledge of the domestic context and how governments justify why their behaviour is not adapted – and they can quickly share information with actors in other countries and activate network members to bring the issue onto the agenda of international organizations.Footnote 61

To loop back to our conventional core agent of international legal change, we find in this historical tracing that states were indeed the central makers and shapers of human rights law at the international level prior to the establishment of the treaty-based system. State silence on water in the UDHR and the ICCPR and ICESCR met increasing claims for its recognition as a right in the 1970s through the advocacy of multilateral agencies and non-state actors, which signalled that environmental challenges around the globe arising from water problems mattered to human rights law and could no longer be ignored. Instead of actively driving a change process from the field of environmental law to human rights law, we find states to have shifted from a centre position to one at the margins, making room for legal change on alternative pathways and through legal interpretation.

4.3 Making water and sanitation co-dependent right(s)

With states not actively driving or blocking water-related discussions of human rights, its supporters made use of this window of opportunity to advocate for formal recognition of water and sanitation as human rights. Their advocacy had to be channelled into strategy, and debates into options, of which there were several, ensued among NGOs, academics and human rights advocates. Should a human right to water be codified in a new treaty or an optional protocol? Or should it be declared in a resolution of one of the intergovernmental bodies? NGOs experienced with the UN human rights system strategized that a human right to water would be best situated in connection to the ICESCR, which included explicit mention of two rights practically contiguous to the right to water: a right to an adequate standard of living and a right to the highest attainable standard of health.Footnote 62 The operative logic herein sought to make use of the general comment, which, although an instrument to that point solely used to interpret a treaty’s existing provisions, seemed a substantive pathway to codify, and ostensibly create, new norms. Previously adopted general comments, like No. 4 on the right to housing, had already interpreted sanitation and water as included in certain contexts.Footnote 63 When members of the network approached the committee and its members, the latter was generally open to the idea, but felt that the time was not yet right for such a bold venture.Footnote 64 There was no discursive opening which would have facilitated an expert path for legal change.

This changed in the 1990s and the discourse on water as a human right was brought to the expert committee by the state parties themselves – probably without even being aware of the consequences. Despite the CESCR’s skittishness to (yet) address a right to water, states parties to ICESCR appeared to at least decide on the treaty body as the right authority to address water-related issues. A content analysis of all state reports and the CESCR’s concluding observations considered between 1993 and 2002 indicates that water had been an issue related to the ICESCR even before it was interpreted as a right inherent to an adequate standard of living under Article 11.Footnote 65 Indeed, the issue of water was addressed by states in their reports to the treaty body before the general comment on a human right to water was drafted; here they not only acknowledged the connection between water and human rights by including water policies and issues in their reports, but also recognized the CESCR’s authority to deal with all issues connected to water by orienting their address toward the treaty body. The CESCR, on the other hand, did not integrate the states’ concerns on water with the same intensity in their concluding observations.

Several individuals within and outside of CESCR were, however, more active in taking up water and sanitation issues in their statements and questions.Footnote 66 In between 1997 and 1999, several days of general discussion and expert meetings regarding a general comment on the right to food took place during CESCR sessions, during which the idea of a separate general comment on the right to water was raised. One CESCR member made it clear that access to clean water was ‘as important as food’,Footnote 67 another suggested that water should be subject to a separate general comment and one member proposed to postpone the discussion on water entirely.Footnote 68 Further nudges to activate the expert pathway came from independent experts in other UN functions. Special Procedures mandate holder Miloon Kothari, the Special Rapporteur on the right to housing, addressed CESCR in November 2000 signalling the willingness of his and other mandates to co-operate with CESCR on emerging issues that have ‘implications for the mandates’: access to water; international co-operation; and land reform. Footnote 69

With the adoptions of General Comment No. 12 on the right to food, in 1999, and General Comment No. 14 on the right to health, in 2000, CESCR had provided interpretations of economic and social rights that had already been discussed with regard to their water-related implications. Accordingly, NGOs involved in these drafting processes built from this infrastructure and pushed for a general comment recognizing the right to water. CESCR decided in 2001 that the time was then right for action. With multilateral events like the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development and the 2003 Third World Water Forum on the horizon, the path of enacting change through the treaty body entirely contrasted with the earlier decades’ sluggishness, evidenced by the rapid turnaround between the decision to draft a general comment on the right to water and its adoption.Footnote 70

The CESCR alone could not draft such a general comment within such a short time frame and transferred the responsibility for the drafting process to one of its members, Eibe Riedel, who became the process’s rapporteur. Riedel was also part of a group of treaty body members who, four years prior to General Comment No. 15’s drafting, developed an outline for general comments to secure their consistency,Footnote 71 became a key driver for the legalization of the norms in the ICESCR and its justiciability,Footnote 72 and as an elected member of the CESCR from 1996–2014, made the professionalization of the instrument of general comments part of his personal mandate. With regard to General Comment No. 15, Riedel reflected on the decision to draft an interpretation centring water and sanitation as being very much made following the pressure from NGOs,Footnote 73 further attesting to the perception of treaty bodies as alternative paths of authority for activating legal change.

As rapporteur, Riedel was the responsible CESCR figure orchestrating the drafting process, which he led in close collaboration with a legal officer at the Center for Housing Rights and Eviction (COHRE), an NGO with whom Riedel had previously collaborated on the drafting of General Comment No. 12. Alongside Riedel, this officer assumed the role of the drafting process’s legal entrepreneur.Footnote 74 The coalition was formed with further outside collaborators. One of them was an expert on water and land issues, of recent employ at a development aid organization, and notably with no experience in human rights work.Footnote 75 She would provide experience and technical expertise in water issues and development. A further collaborator was the WHO’s water expert amid drafting a WHO bookletFootnote 76 on a right to water and sanitation with regard to the Millennium Development Goals, who closely collaborated on the draft’s health-related aspects.

The official first Draft of General Comment No. 15, dated to 29 July 2002, was sent to other actors both on an individual basis and through more formal bureaucratic channels. The secretariat of the CESCR circulated the draft among selected UN agencies and academics with an invitation to both participate in the discussion of the draft during the CESCR’s next session in November 2002 and to comment on it with input. As the date for adoption was envisaged for November – therefore extremely soon – it was a tactical decision to keep the Draft non-public and make no open call for statements.Footnote 77 The day of discussion for the draft general comment was split into two parts: one public meeting, which included statements by all relevant stakeholders and was generally in favour of the general comment and the inclusion of sanitation and the regulation of privatization to its text,Footnote 78 and one non-public in the afternoon. This second meeting followed a different dynamic of representation and line of argument: no state party was present, but there were representatives from the World Trade Organization (WTO) and civil society actors. In this meeting, strong opposition from WTO to the general comment was debated and civil society actors and committee members alike tried to advance counter-arguments.Footnote 79

In these drafting discussions, states played a marginal role. The front-line positions in the process were taken by NGOs, treaty bodies and international organizations like the WHO and WTO. Of all invited stakeholders to the discussions, only Japan sent a delegate, which was to emphasize the timeliness of the topic with the upcoming water meeting in Kyoto. But while states did not further contribute to the drafting process, the adoption of General Comment No. 15 did provoke their knee-jerk involvement as stakeholders, as its adoption created immediate backlash in giving codified provision to something (water) that stood non-enshrined within the core human rights treaties. There was generally alarm that the text of General Comment No. 15 would further deconstruct ‘an adequate standard of living … into an all-encompassing concept containing several novel rights’;Footnote 80 and likewise saw its adoption more generally as part of a worrying trend of treaty bodies departing from their intended role – i.e., to interpret the content of the human rights regime’s existing obligations – to instead create new legal norms via general comments and thus overstep their mandate. On the right to water, some states ultimately felt pressured to formally deny its existence altogether. In a view submitted to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in June 2007, the United States of America led this dissent to the comment’s interpretative substance, making clear that they did not ‘share the view that a “right to water” … exists under international human rights law’.Footnote 81 Given the US’s status as a non-ratifying signatory to the ICESCR, the US statement can be read as an attempt to clarify its opposition with regard to future policy and law-making. The US are forced to act as spoilers to the legal change process although change happened on a path they do not control.

Overall, General Comment No. 15 marked the central milestone for the recognition of water as a human right. After decades of non-recognition and blockade in formal treaty-making, the expert body path, put in motion by a transnational coalition led by an expert body member and third-party actors, proved to be the most promising for the advocates for legal change.

4.4 Formalizing human rights change: Water and sanitation as independent rights

Although General Comment No. 15 was perceived as innovative and far-reaching in its legal substance and sparked backlash and debates among legal academics,Footnote 82 its advocates demands were not all met, with certain concessions having to be made. CESCR, for one, had been ‘pressed by NGOs and international health experts to imply the right to sanitation along with water’.Footnote 83 But this implication never made it into the comment, an omission that was the fault here not of the state but the expert committee, who acted as blockerFootnote 84 in citing the lack of support for such a right in international law.Footnote 85

This support was eventually realized by way of alternative authorities shortly after the adoption of the General Comment No. 15. The more the right to water became subject to domestic court decisions, policies and human rights advocacy,Footnote 86 the easier it became for the CESCR to justify a right to sanitation based on international law – to reference, that is, tangible, rather than a dearth of support. Accordingly, in the committee’s later-drafted General Comment No. 19 on the right to social security in 2007, sanitation was distinctly named as a right alongside food, clothing, housing, and water.Footnote 87 Further evincing the central influence individual non-state actors on an expert body can have in engineering tangible change to human rights law, the rapporteur for this Draft was also Eibe Riedel, this time together with Virginia Bras Gomes.Footnote 88 States at this time turned from the majority being bystanders to the majority acting as catalysts for the legal change process. With the establishment of the mandate for an Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation by states in the Human Rights Council in 2008, the legal development of a human right to water and sanitation was redirected from the expert path of the Special Procedures mandate holder Catarina de Albuquerque, to the intergovernmental level in the Human Rights Council. Her 2009 report to the Council highlighted the global development towards a right to sanitation.

In 2010, the GA adopted Resolution 64/292 with the title ‘The human right to water and sanitation’, referring to General Comment No. 15 as its basis. No state voted against the resolution. A human right to water was herewith recognized by 122 governments and affirmed the treaty body’s authority in the development of the norm. The omission of a right to sanitation in the General Comment mobilized the right’s supporters among governments, specialized agencies and civil society, leading to this Resolution, which codified sanitation as a human right as essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights. On the supportive side, the Draft Resolution A/64/L.63/Rev.1 was presented by Bolivia.Footnote 89 In its statement, the Permanent Representative Pablo Solón Romero rejected ‘[s]afe drinking water and sanitation’ as ‘elements or components of other rights’ and confirmed ‘the right to safe drinking water and sanitation’ as ‘independent rights’.Footnote 90

The relatively high number of abstentionsFootnote 91 was justified along various lines of arguments: As mentioned, the US denied that a right to water and sanitation in an international legal sense existed at all. Canada likewise pointed to the absence of an international agreement to justify its abstention, with the United Kingdom even more emphatic in their dissent, reiterating that water was neither an independent human right nor customary law. But although these states questioned the legality of the right(s), they did not actively block its formalization by voting against the Resolution. Even Ethiopia, which justified their abstention with reference to the Resolution as a ‘violation of state sovereignty’, did not make use of the vote rejecting the Resolution.

A second reason basing states’ abstention from voting for (or against) the GA Resolution stemmed from the parallel efforts by the Human Rights Council in Geneva to draft a resolution on a right to water and sanitation. Beyond those mentioned above, the majority of states abstaining – among them Turkey, New Zealand, Australia, Botswana, Japan, and the Netherlands – justified their non-vote with the feeling that ‘it was premature for the General Assembly to take a vote’Footnote 92 before the Human Rights Council. The ‘unnecessary political implications’ of the General Assembly ‘ad hoc declaration’ were further highlighted by the Netherlands.

In any case, the trend towards formalized change in international law continued and in September 2010, the Human Rights Council consensually adopted Resolution 15/9 affirming the decision of the GA to acknowledge a human right to water and to sanitation – not as independent rights but ones that ‘derived from the right to an adequate standard of living and inextricably related to the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as well as the right to life and human dignity’. The Council further reflected this change also by a denomination of the mandate of Catarina De Albuquerque from Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation to a Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation in 2011.

Casting the narrative back, we thus see that through the adoption of General Comment No. 15, CESCR – which itself adopted a statement in 2010 acknowledging the right to sanitationFootnote 93 – became the key framework for the recognition of a right to water and sanitation in human rights law. Other treaty bodies subsequently adopted general comments referring to the human right to water, with new treaties adopted after General Comment No. 15 likewise including the human right to water in their text, see, e.g., CRPD’s Article 28. The work of the UN in global development came to promote ‘water and sanitation’ as a target in the Millennium Development Goals to a goal of the Sustainable Development Goals. And to recall the comment’s earlier-mentioned impact on domestic law and policies: more than 50 countries now accept the right to water in their domestic laws and courts continue to give explicit reference to General Comment No. 15 in rendering decisions.Footnote 94 On the civil society front, the re-framing of water as a basic human need and a right gave leverage to NGO initiatives pressuring local and national governments to adopt policies which provide sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use.Footnote 95 Relatedly, the General Comment facilitated the water-related work of human rights, environment, and development NGOs, and many stakeholders have emphasized its importance for the development of monitoring mechanisms.Footnote 96

5. Discussion: Human rights change as a consequence of states-as-bystanders

As the above sections trace, the human right to water evolved from a complete absence in human rights law to being recognized today as the independent human rights to water and sanitation. States did not formally recognize the right to water and sanitation in human rights law for decades. Their establishing of expert bodies through the treaties of the UN human rights system opened the door for alternative authorities to become agents of human rights change, relegating states to a bystander role in its process. Water as a human right emerged on the agenda because of the efforts of a variety of civil society actors and issue professionals – in human rights, international development, environment and humanitarian affairs – who beyond serving as tireless advocates for the recognition of the right under human rights law, brought global perspective and expertise to the issue area. Through their advocacy, they transformed water quality and scarcity problems into a problem-solving norm – water as a human right.

These facilitating efforts, aimed to codify access to water by way of the CESCR, highlights the way in which water’s path of change routed centrally through treaty interpretation by the expert bodies, rather than states. Treaty bodies, albeit originally established as an agent for monitoring treaties, have rapidly acquired the prescriptive agency to develop human rights through their treaty interpretations.Footnote 97 As such, they have established themselves as alternative authorities to the state for actors seeking change, even in cases of state opposition. Indeed, what makes the change process of the rights to water and sanitation even more remarkable is that it was realized notwithstanding strong resistance from powerful stakeholders like the USFootnote 98 and private companies against obligations for the privatization of water provision. This success, however, culls from state bystanding – never did these actors articulate their opposition directly to the CESCR, instead remaining at the margins throughout the drafting process. As a consequence of their inactions and unresolved discursive space on normative meaning, other actors joined forces and evaluated options for action – which then pressured states to take back a more central role in lawmaking.Footnote 99

This state-as-bystanders effect describes on the one side the phenomenon that advocates for human rights change shift their efforts for legal change processes away from the multilateral path to the expert body path. With states not actively blocking or driving such processes and norm, advocates determined to see this change, they turn to alternative authorities. In human rights law, these are state-empowered expert bodies monitoring treaties. As a consequence of coalition-building of treaty body members, civil society actors and transnational professionals, change is codified in treaty interpretations. Generally non-binding, these interpretations quickly become advocated for and implemented in local contexts by the members of the coalition and their wider networks.

6. Conclusion

The legal change process of the human rights to water and sanitation illustrated the possibility of change to human rights law when states are bystanders within a legal system they themselves created. While states vary in their individual approach to blocking or driving change processes in international law, and with different motivations and interests, non-action at the intergovernmental level does not prevent change agents from seeking alternative paths. The omission of water in the UDHR and the two Covenants did not lead to state action for change in the norm’s legal status in the field of human rights. Without states actively driving or blocking change processes but opening up a discursive space in environmental law, other change agents turn to alternative human rights authorities to see change formalized. While the multilateral path facilitated the mobilization structures of NGOs, it was the expert path that provided a turning point for change via the instrument of treaty interpretation. A coalition between treaty body members, civil society actors and individual experts on water issues filled the changemaking void left by states, who took a bystanding vantage to the process. Accordingly, states were relegated to the sidelines as General Comment No. 15 saw rapid and impressive development, a change process whose momentum lost no steam even as some states expressed objections on the CESCR overstepping its mandate and arguments about the legal foundations of such a right to water, hereby attempting to act as spoilers. Yet, most states came to recognize the right to water and sanitation as essential for the realization of universal human rights protection. Only a couple of years after the adoption of General Comment No. 15 did states return to the process of legal change as participants – albeit not in the central role they started with – by formalizing their recognition of rights to water and sanitation in a GA resolution.

This empirical tracing lends support to the argument that once states choose, or are relegated to the margins of legal change, with the role of driver taken up by other authorities, they can still come back as a catalyst for the process on the whole but are precluded re-assumption of a central role as the process’s driver or blocker in those processes where the coalition of actors for legal change has formed and developed to an intimate degree. Once a bystander to legal development by other authorities, states cannot reverse the progress made from a central spot but may take an intermediate role. To stay within the terminology of the present framework for legal human rights change: if states do not actively drive or block legal change after the absence phase, alternative institutions gain interpretative authority over the direction of change. Together with legal, political and societal actors, they can gradually bring in a norm to international human rights law as a condition for other rights and expand it to a dependent right status. Ultimately, states finalize the change process to recognizing a norm as independent right, e.g., by adopting resolutions. This observation also emphasizes what an assessment of formal law-making mandates necessarily overlooks: that institutions making and shaping international law, like treaty bodies, do not act themselves but rather bear the individual actions of their constituent members, who ultimately are the ones making interpretations and decisions on international law.Footnote 100

States are certainly the founders and primary addressees of the treaty regime, but they have delegated the monitoring and interpretation of the standards to independent expert committees, who are expected to act as international intermediaries.Footnote 101 As seen with the treaty bodies, these intermediaries do not always act in the spirit of their principals, with some exceeding their mandates with progressive general comments, as the above analysis shows. Particularly the role that civil society actors (can) play through transnational coalitions with the expert body,Footnote 102 change ‘the bilateral and formal nature of the interstate monitoring regime in significant ways’.Footnote 103 Nevertheless, states hold the power to end the practice of the treaty bodies, as well as numerous ways to shape its bounds. This article shows what spaces open up when states leave the central role as driver or blocker of legal change, but it is not an example for ‘lawmaking without governments’.Footnote 104 For one, they can elect the members of the expert committees at their discretion, and thereby can choose candidates more or less strict in a treaty’s application or those with more or less expertise in a given legal field. For another, they can exercise their particularly powerful thumb on budgetary support in contexts where the authority and decisions of a committee exceeds their tolerance.

While the illustration of the argument in this article focused on a single case of legal norm change, it can be transferred to other cases. Many challenges for human rights have recently been addressed through soft law rather than formal state-led initiatives like treaty-making, in particular through outputs of the treaty bodies.Footnote 105 In human rights, the multitude of actors – rather than fixed institutions – further manifests in the fact that decisions by treaty bodies are implemented to a great extent by other (non-)state actors.Footnote 106 Unambiguous obligations of socioeconomic rights to fight increasing global inequality are thus even more important for their future protection.Footnote 107 While this might be argued to present area-specific ‘human rights experimentalism’,Footnote 108 the observation that state-empowered entities step in as authorities for legal change can be extended to such entities in other fields.Footnote 109

The observations in human rights reflect a wider phenomenon in international law: While fewer multilateral treaties are concluded in international law, said to be symbolizing a ‘treaty fatigue’Footnote 110 among states, normative change increasingly happens through interpretation. International Relations scholarship has shown how states strategically use interpretive tactics to influence how other states interpret legal obligations.Footnote 111 In particular, the literature on international courts has explained how judges and communities of legal practice are able to develop and change legal norms through interpretation.Footnote 112 In light of this discourse, future International Relations and International Law scholarship has to take the varying roles of states for legal change processes seriously. More attention needs to be devoted on how the developments presented in this article impact the values and structure of international lawFootnote 113 and specifically, whether human rights law transforms from an international to a transnational legal structure, leaving states as bystanders to its future development.

Annex

A. Discussion of access to water in discussion of state reports by CESCR members prior to GC15

As indicator for poverty/ economic crisis

-

– Jamaica, 21 November 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.73 (GRISSA)

-

– Solomon Islands, 19 November 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.37 (SCHMÜRMANN-ZEGGEL, Amnesty International)

As indicator for discrimination (women/ national groups/ rural areas)

-

– Algeria, 15 November 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.66 (BARAHONA-RIERA)

-

– Nepal, 22 August 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.45 (MARTYNOV)

-

– Finland, 15 November 2000, E/C.12/2000/SR.61 (RIEDEL)

-

– Cameroon, 23 November 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.41/Add.1 (PILLAY)

-

– Mexico, 25 November 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.45 (CEASU)

-

– Israel, 18 November 1998, E/C.12/1998/SR.33 (BONOAN-DANDAN, AHMED)

-

– Israel, 17 August 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.39: (AHMED, MALINVERNI)

Insufficient access to safe drinking water

-

– Congo, 05 May 2000, E/C.12/2000/SR.16 (THAPALIA)

-

– Egypt, 03 May 2000, E/C.12/2001/SR.13 (TEXIER, THAPALIA)

-

– Dominican Republic, 19 November 1997, E/C.12/1997/SR.31 (SADI, GRISSA)

-

– Iraq, 21 November 1997, E/C.12/1997/SR.35 (THAPALIA)

-

– Azerbaijan, 26 November 1997, E/C.12/1997/SR.40 (PILLAY, SADI, GRISSA)

-

– Syrian Arab Republic, 15 August 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.35 (PILLAY, SADI)

As indicator for adequate standard of living

-

– Tunisia, 06 May 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.20 (RIEDEL)

-

– Argentina, 18 November 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.35 (TEXIER)

-

– Israel, 18 November 1998, E/C.12/1998/SR.33: (WIMER ZAMBRANO)

-

– Uruguay, 28 November 1997, E/C.12/1997/SR.44 (SADI, AHMED)

-

– Paraguay, 30 April 1996, E/C.12/1996/SR.2 (TEXIER)

-

– Portugal (Macau), 21 November 1996, E/C.12/1996/SR.33 (ADEKUOYE)

-

– Egypt, 03 May 2000, E/C.12/2001/SR.13 (SADI)

As indicator for health

-

– Solomon Islands, 30 April 1999, E/C.12/1999/SR.9 (RIEDEL)

-

– El Salvador, 10 May 1996, E/C.12/1996/SR.18 (AHMED)

-

– Bolivia, 03 May 2001, E/C.12/2001/SR.17 (RIEDEL)

-

– Egypt, 03 May 2000, E/C.12/2001/SR.13 (SADI)

-

– Cyprus, 19 November 1998, E/C.12/1998/SR.36 (RIEDEL)

As indicator for right to food

-

– Morocco, 22 November 2000, E/C.12/2000/SR.71 (RIEDEL, THAPALIA)