Introduction

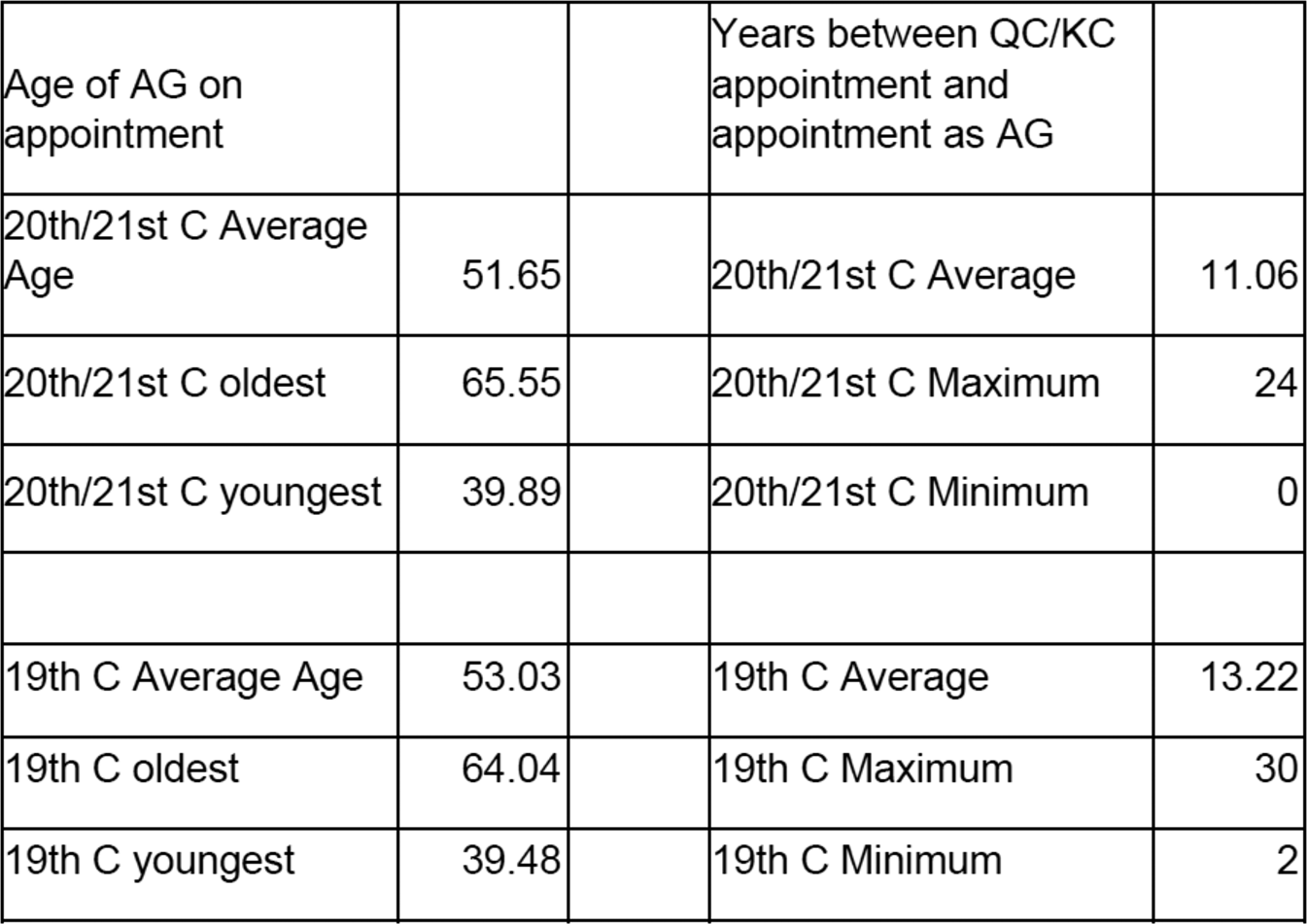

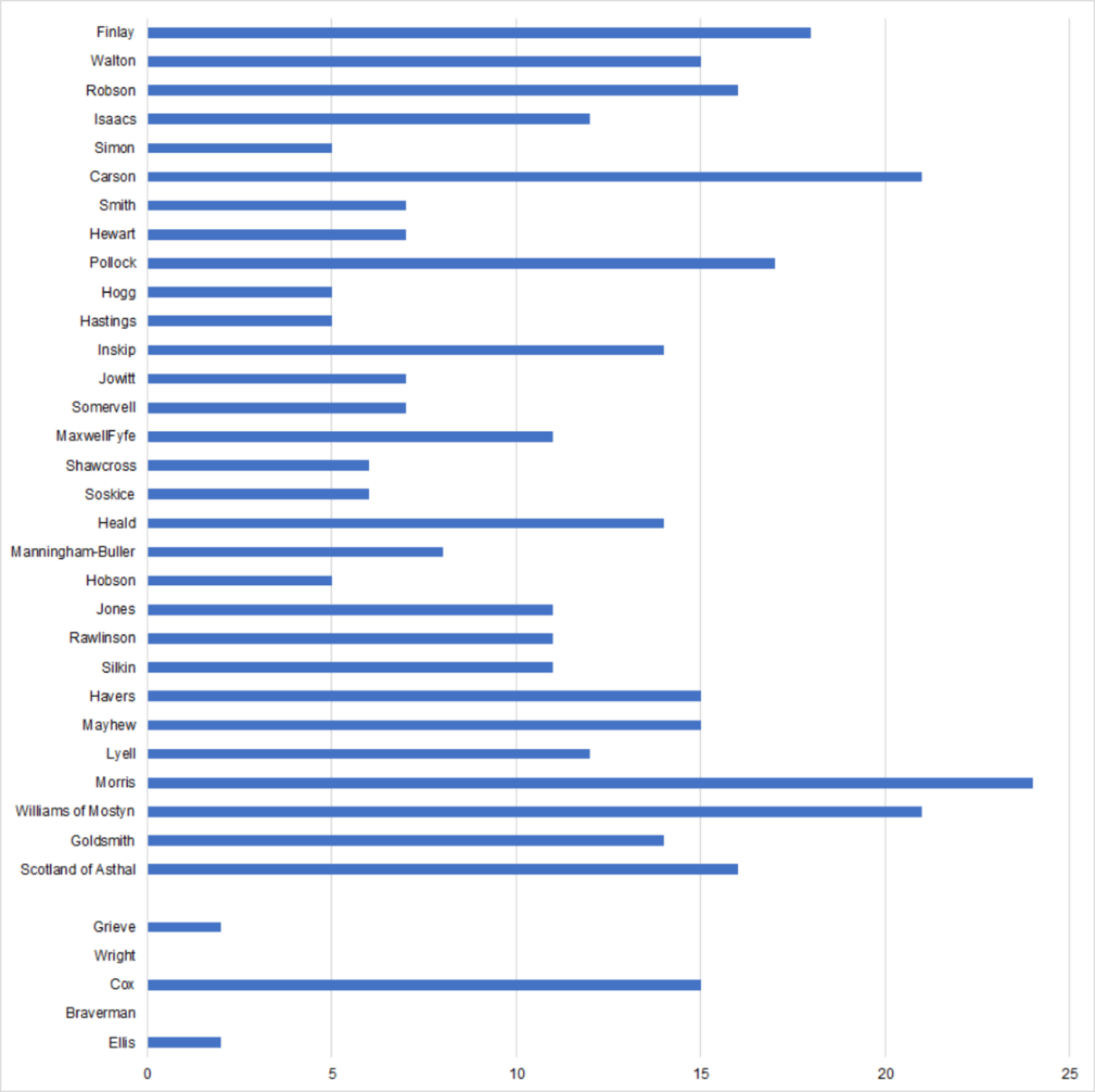

Suella Braverman's appointment as Attorney-General in February 2020 led to many critical comments in both the social and traditional media, focusing on her relative inexperience as well as her political views.Footnote 1 Her appointment was notable for a number of reasons. She became only the second woman (and the first Conservative woman) to hold the office of Attorney-General for England and Wales and the first person of Asian ethnicity to have that role.Footnote 2 Under 40, she became the youngest person to be Attorney-General since Spencer Perceval in 1802. She was almost 12 years younger than the average since 1900 (see Figure 1) and only Sir John Simon had a slightly shorter period between being called to the Bar and being appointed Attorney-General (15 and 14 years respectively against an average of 26.5 years). She had only ten years’ experience at the Bar before becoming a Member of Parliament and had under half the Parliamentary experience of her average post-1900 predecessor before her appointment. Furthermore, she was not a Queen's Counsel until a few days after her appointment,Footnote 3 which, while not unprecedented, is something for which there was little direct precedent; her post-1900 predecessors on average took silk a decade beforehand.Footnote 4 One such precedent, however, was her predecessor bar one, Jeremy Wright, who – at 41 – was just under two years older on appointment (being then the third youngest since Perceval, after Sir John Simon and Sir Robert Gifford). His appointment, too, received a negative press.Footnote 5 In contrast to their youth and relative inexperience, the incumbent separating their tenures seemed far closer to the archetypical Attorney-General. Geoffrey Cox became a QC 19 years after he was called to the Bar and a couple of years before he became an MP, served a number of years on the backbenches and had been a head of chambers. However, he was, in fact, the fifth oldest person to become Attorney-General in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. One thing all three had in common, along with every Attorney-General for the preceding 20 years, is that none had been Solicitor-General, the junior Law Officer, beforehand; that being one of a number of distinct changes over the years (a trend, perhaps temporarily, interrupted by Michael Ellis stepping up from Solicitor-General while Suella Braverman went on maternity leave).

Figure 1. Table showing average age and age range of Attorney-Generals and average years between appointment as QC/KC and appointment as Attorney-General

1. A short history of the posts of Attorney-General and Solicitor-General

Both roles date back over 500 years in both title and nature and their less recent history will not be recounted in detail here.Footnote 6 However, a short historical overview is necessary to set the roles in context.

Growing out of the roles of King's Attorneys and King's Sergeants (who in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries brought actions on behalf of the Crown), the first use of the term Attorney-General occurred contemporaneously with the expansion into a political as well as litigious role. As Sir Hartley Shawcross put it ‘as the functions of sovereignty became more complex and extensive and acquired a more public character, it was natural that the functions of the King's Attorney should become wider’.Footnote 7 1461 saw the newly designated Attorney-General summoned by the King to go to the House of Lords to advise on legal matters and, while the title of Solicitor-General did not appear for another half-century (to be more specific 1515), a King's Solicitor who acted as a deputy or assistant to the Attorney-General was also appointed in 1461.Footnote 8

While the Solicitor-General was to become the effective deputy to the Attorney-General, for some time the Attorney-General was seen as the Monarch's and the House of Lords’ advisor, whereas the Solicitor-General was – at least in part – the House of Commons’ man. Richard Onslow was both Solicitor-General and Speaker, concurrently, in the late 1560s, starting a short-lived expectation, but not a convention, that the Speakership could, in the words of Harry Hylton-Foster, be ‘considered a kind of perquisite of the office of Solicitor-General’.Footnote 9 While, two out of four of the Speakers following Onslow held both roles for some of the time,Footnote 10 since then people holding both roles concurrently, or at all, have been very few and, indeed, often far between (there were two such Attorney-Generals in the seventeenth century, both of whom were Speaker first, one being the only other instance of the roles being held concurrently for at least part of the time; one in the mid-eighteenth century; one at the turn of the nineteenth century; and one in the twentieth century).Footnote 11

In stark contrast, the Commons were initially suspicious of the Attorney-General. While Francis Bacon served as MP and Attorney-General at the same time, the House of Commons resolved in 1614, during his tenure, that, thereafter, ‘no Attorney-general should at any Time be of the House’Footnote 12 which led, for example, to Sir Thomas Coventry, a highly regarded Solicitor-General, being unseated by that resolution before he could retake his place in the Commons, on being both elected to Parliament and promoted to Attorney-General, in 1621.Footnote 13 This prohibition, and the legislative distinction, however, did not last long. By 1700, as Elwyn Jones notes, Law Officers had ceased to attend the Upper House and Attorney-Generals regularly served in the Commons before then, although he noted as exceptions that ‘at least two occupants of the office – Sir William Jones, the “bull-faced Jonas” of Absalom and Achitophel and Sir John Trevor – were not in the Lower House’.Footnote 14 They were not the only two who did not sit in the House of Commons in that period, including Sir Edward Herbert (1641–1645) whose impeachment led to him ceasing to be an MP but not Attorney-General.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, it is clear that membership of the House of Commons was by then no means a bar;Footnote 16 and it became a de facto requirement from the start of the eighteenth century.

As the early role of advising the House of Lords, specifically, disappeared in practice, the Attorney-General and his deputy became less counsel for the King and more ministerial and parliamentary advisors while at the same time maintaining their own private practice as leaders of the Bar. This combination was emblematic of the independent nature of part of the roles. While the Law Officers were, and are, advisors to the executive and the legislature and accountable to Parliament they also represented the independent Bar and worked for the public interest. A level of independence remained even after the 1890s saw an end to both the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General having lucrative private practices alongside being the government's lead lawyers. It is this factor of a level of independence, which has been described as ‘legally insecure but conventionally safe’,Footnote 17 that is the reason why the Attorney-General (and his/her deputy) may advise the Cabinet but are not – and with a few exceptions have not been – members of it, as examined below.

The role of the Attorney-General

The role of the Attorney-General (and thus the Solicitor-General, who since the Law Officers Act 1997 can formally exercise all functions of the Attorney-General) was, and remains, multi-faceted and juggling those facets could be problematic. The role can be viewed as having five overlapping segments: ministerial, advisory, parliamentary, litigatory and ex officio, combining the party political and guardianship of the public interest. While the Attorney-General is by no means the only member of government who has to balance the political and a legal role,Footnote 18 the Law Officers have to do so more frequently than any other.

(a) The ministerial function

The Attorney-General's Office is currently described as a ‘small ministerial Department’Footnote 19 which supports the Attorney-General and the Solicitor-General in their work as Law Officers. This work includes the superintendence of the non-ministerial departments, namely the Crown Prosecution Service (and its Inspectorate), the Serious Fraud Office and the Government Legal Department,Footnote 20 which together with the Attorney-General's Office form the Law Officers’ Departments. While small, indeed on some figures the smallest department after the Department for International Trade, it nonetheless has a spend of over £600 million and some ministerial accountability is required, albeit now at a distance so as to respect prosecutorial independence.Footnote 21 The Law Officers are clearly designated ministers within Schedule 2 to the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 and Schedule 1 to the Ministerial and other Salaries Act 1975 but they are no ordinary ministers in terms of obligation and, indeed, pay (the Attorney-General, following the reforms to the Lord Chancellorship, now being the highest paid minister and the Solicitor-General earning thousands of pounds more than non-cabinet ministers, reflecting the lack of the lucrative side-practices of old).Footnote 22 The different position as ministers can be summed up by two quotations from two former Law Officers, highlighting their role as guardians of the public interest: Lord Mayhew of Twysden told a House of Lords committee ‘The Attorney-General, in my view, o[w]es loyalty first to the Queen, to the Crown in person (he is Her Majesty's Attorney-General), secondly to the law and thirdly to his colleagues in government’;Footnote 23 and Sir Edward Garnier, recounting what Harold Macmillan said to Peter Rawlinson on his appointment – ‘I want you to be Solicitor General, your first loyalty should be to the rule of law, your second loyalty should be to Parliament, and your third and very much third loyalty should be to my administration’ – has commented ‘And that I think was a very proper description of the role of the law officers – not much understood by the modern member of parliament and the modern political minister’.Footnote 24

While the Cabinet Office's List of Ministerial Responsibilities describes the Attorney-General as having ‘Cabinet level membership of the Government’, it has been the general convention that he or she only attends when invited. Lord Morris of Aberavon, who held the post for the first two years of the Blair Government, has remarked that ‘Certainly I was never a member of the Cabinet and I never attended Cabinet but I did attend the War Cabinet on Kosovo on many occasions and, of course, many Cabinet committees’.Footnote 25 His predecessor bar one, the then Sir Patrick Mayhew, has noted that in his time ‘it was the established convention that you were of Cabinet rank but not a member of the Cabinet, and you went by invitation to deal with the specific item of business and then you left’, underlining that the importance of doing so was because the Cabinet have to accept legal advice from the Attorney and it being ‘more difficult for them to do so if he had been present taking part in a contested debate about policy’ as ‘they might be tempted to think that if he gave them adverse advice to their political interest that was simply [to] reinforce the view he had taken in the course of argument’.Footnote 26 Dominic Grieve, the 2010 Coalition's first Attorney-General, found that attending Cabinet was important to help keep him in the loop while being of the view that ‘pontificating in Cabinet, in fact that would be, I think, a very dangerous thing to happen’.Footnote 27

The ministerial function extends to policy matters as the Attorney-General has responsibility, along with the Home Secretary and Secretary of State for Justice, for the efficiency, effectiveness and accountability of the criminal justice system. However, the level of policy engagement varies. Lord Goldsmith launched a major review into fraud, a Labour manifesto commitment, in his time as Attorney-General,Footnote 28 whereas Dominic Grieve wanted to focus on the advisory side of the role:

Whereas previously, the law officers had begun to creep into policy-making as a small policy-making department taking the lead in some criminal justice policy issues… [a]nd although I wanted to be able to provide an input into that, my conclusion had been that to try to lead on that, when the law officers’ department is tiny, is a very difficult thing to do and I think would be better to actually focus on the advisory side of the work.Footnote 29

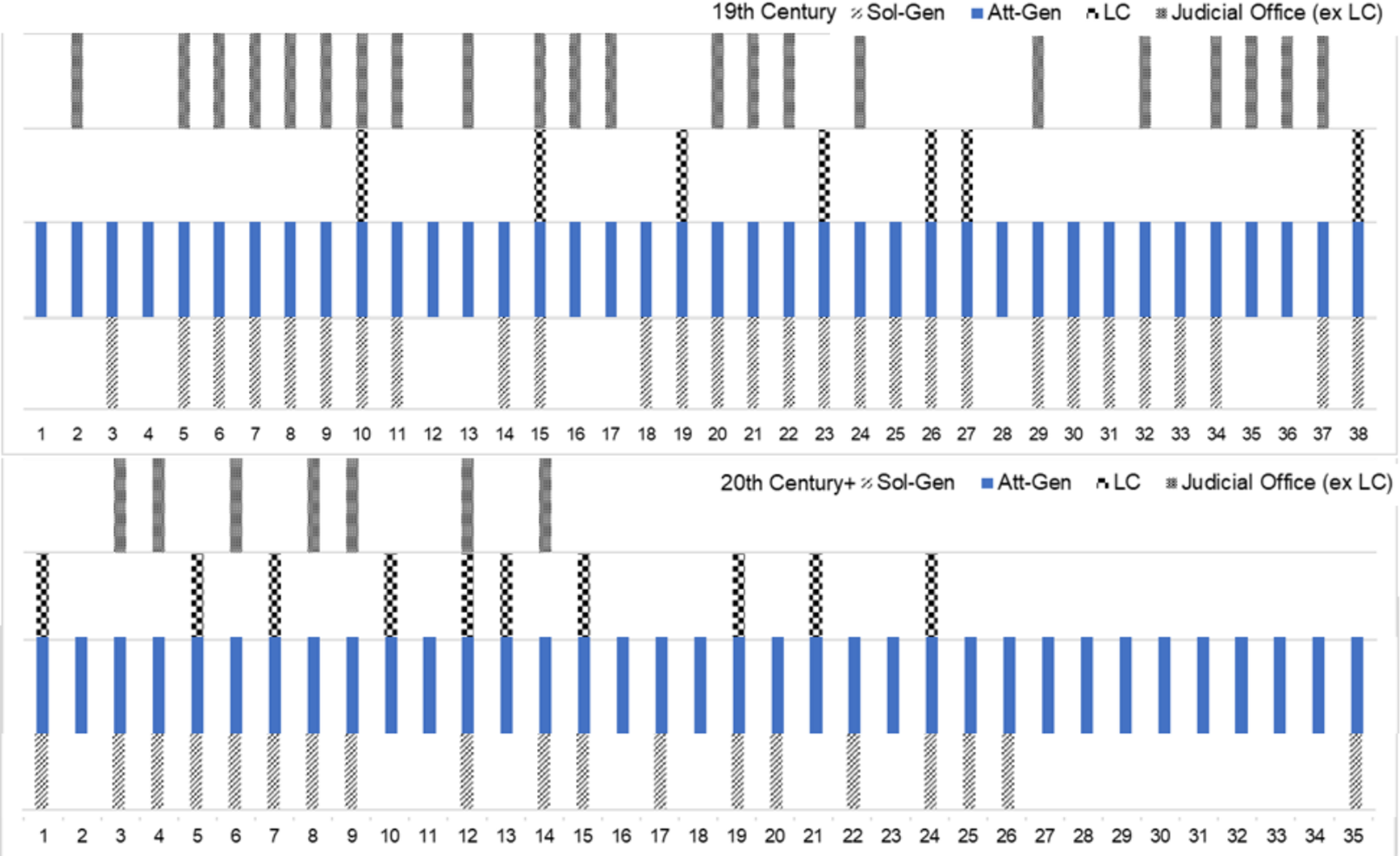

Despite being a ministerial role, and because of its nature, it is generally not a stepping-stone to high ministerial office. As Geoffrey Cox remarked shortly before being replaced by Suella Braverman, ‘I had not expected a frontline political career… and to some extent the peculiarity of the attorney general role means that I still haven't had a frontline political career’.Footnote 30 Not since the 1950s has an Attorney-General gone on to major political office (Frank Soskice having been Attorney-General under Attlee and then becoming Home Secretary under Wilson 13 years later),Footnote 31 with only three others, earlier in the twentieth century, having gone on to hold a great office of state. For the most part Attorney-Generals had not held highly politicised ministerial posts beforehand, Suella Braverman's role as a Brexit minister being something of a departure. Indeed, as illustrated in Figure 2, the nineteenth-century tradition was that the Attorney-General would have a judicial rather than a ministerial career, with 60% going on to hold high judicial office – or 70% if including the Lord Chancellorship. This reduced during the twentieth century, which saw a marked decline to only 25% going on to hold such offices other than the Lord Chancellorship (with none after 1946 when Sir Donald Sommervell (Attorney-General 1936–1945) became a Lord Justice of Appeal).Footnote 32 That declining number included Lord Hewart, whose performance and wide recognition as ‘the worst Lord Chief Justice of the twentieth century’, according to Lord Toulson, ‘led to the end of the convention by which the office of Lord Chief Justice would be offered to the Attorney-General’.Footnote 33 While there reportedly was an expectation among some Attorney-Generals to be offered the post if a vacancy arose, it is notable that only 20% in the nineteenth century and 10% in the twentieth century went on to become Lord Chief Justice (and often after a delay). In contrast to other judicial roles, there was over the same period a doubling in the proportion who became Lord Chancellor (from 17.5% in the 1800s to 35% in the 1900s), but there have only been three since the end of World War II (namely Manningham-Buller, Jones and Havers (and two former Solicitor-Generals: Falconer and Buckland)).

Figure 2. Charts showing nineteenth and twentieth/twenty-first century Attorney-Generals who have also been Solicitor-General, Lord Chancellor and Justice of the High Court or above

Looking towards their earlier ministerial careers, over two-thirds of twentieth century Attorney-Generals (19 out of 28) had previously been Solicitor-General,Footnote 34 as had nearer three-quarters (29/40) of nineteenth-century incumbents.Footnote 35 However, in a marked change none of the ten Solicitor-Generals since Sir Nicholas Lyell in 1992 had gone on to become Attorney-General (until Michael Ellis was promoted to cover for Suella Braverman's maternity leave). By contrast, historically it was rare for Attorney-Generals to have previously held junior ministerial office, such as Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller having served as a parliamentary secretary in the Ministry of Works for less than a year at the end of the Churchill wartime administration before going on to be Solicitor-General and then Attorney-General in the 1950s and early 1960s. A trend for some prior ministerial service can be detected from the tenure of Sir Patrick Mayhew who previously served for around four years, first at the Department of Employment and then the Home Office, before becoming a law officer in Margaret Thatcher's second administration. His successor, Sir Nicholas Lyell, was a parliamentary under-secretary at the Department of Health for just under a couple of years and he in turn was succeeded by Tony Blair's first Attorney-General, Sir John Morris, who had been shadow Attorney-General for the previous 14 years and had been Secretary of State for Wales in the last Labour administration (as well as previously a minister for defence and under-secretary for power and for transport). Lord Williams of Mostyn had spent two years at the Home Office and been deputy leader of the House of Lords before becoming Attorney-General after Morris but his successors, Lord Goldsmith, Baroness Scotland of Asthal and, on the election of the Coalition government, Dominic Grieve, did not have ministerial experience (though he had been shadow Home Secretary) and nor did Sir Geoffrey Cox. Jeremy Wright (Cox's predecessor), Suella Braverman (Cox's successor) and Michael Ellis (Braverman's maternity cover) can be argued to have had a more political past. It is, perhaps, one thing for a Law Officer to have worked in the Home Office given the legal link, or other less glamorous or politically heated role, but another to have been in a highly-charged role such as Minister for Brexit (in the case of Suella Braverman) or a whip (as with Jeremy Wright and Michael Ellis). This could exemplify a shift in the politico-legal role toward the political.

(b) The provision of advice

As noted by Dominic Grieve above, the provision of advice to the government is a major part of the Attorney-General's duties and indeed has been over the years. A debate in the House of Commons in 1887 noted that the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General were asked for their opinion in over 350 non-contentious cases in each of 1884, 1885 and 1886 as well as contentious and patent cases.Footnote 36 There is also, however, a separate – and potentially clashing – responsibility to Parliament (‘certainly the House of Commons, and I suspect the House of Lords’ according to Lord Morris of Aberavon).Footnote 37 The advice given to government and Parliament may differ in nature, with the advice to government generally remaining confidential by convention, whereas advice to Parliament may be a public distillation of the same issues, but lacking the detailed appraisal of risks, or be on different matters. The Ministerial Code notes at paragraph 2.13 that ‘[t]he fact that the Law Officers have advised or have not advised and the content of their advice must not be disclosed outside Government without their authority’ and Erskine May confirms that ‘[b]y long-standing convention, observed by successive Governments, the fact of, and substance of advice from, the law officers of the Crown is not disclosed outside government’, the purpose of the convention being to ‘enable the Government to obtain frank and full legal advice in confidence’.Footnote 38 Further reasons for confidentiality which have been put forward are legal professional privilege (as with any client) and the operation of the doctrine of collective cabinet responsibility.Footnote 39 The former is subject to challenge, such as by Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury, cited by Murphy, questioning whether constitutionally the government has a separate legal existence from the people and following the Brexit disclosure whether advice may be released as standard,Footnote 40 and by the view that it is the convention rather than privilege per se that protects the advice.Footnote 41

While there are notable instances of when advice has been made public reluctantly (such as Lord Goldsmith's advice on the legality of the invasion of Iraq and Sir Geoffrey Cox's advice on the legality of proroguing Parliament during the Brexit negotiations), restrictedly (Sir Nicholas Lyell's advice during the Maastricht debate)Footnote 42 and strategically (such as Sir Geoffrey Cox's advice on the Northern Ireland Protocol during the Brexit legislation), the convention limits analysis of the extent of the advisory role, a point noted by Robert Buckland (Solicitor-General, July 2014–May 2019):

It is not possible to comment on individual pieces of advice because of the Law Officers’ Convention… [but] if one looks at the volume of legislation that is created in a given parliamentary session and presumes that a Law Officer has advised at least on its preparation for passage through Parliament, then that may give … an idea of the time spent on the government's parliamentary business.Footnote 43

There has, however, been a study of historic examples using declassified papers which shows the ‘extraordinary range of subjects’ on which Sir Hartley Shawcross had to advise, from constitutional developments in India and Ireland to vacant bishoprics in Chelmsford and St Albans and from capital punishment and war crimes to the powers of education ministers under the Education Act 1944.Footnote 44 While Sir Hartley was Attorney-General in the unusual years immediately following World War II, the range is not unusual. Other declassified cabinet records show, for example, Sir Robert Finlay advising on what would happen if the Russian fleet took refuge from pursuit by the Japanese fleet in a British port leased from the Chinese;Footnote 45 Sir William Jowitt advising on whether the German-Austrian customs union of 1931 was in breach of the Treaty of St Germain;Footnote 46 and Sir Henry James's 1884 draft Bill relating to the sale of land by landlords to tenants in Ireland.Footnote 47

While the broad training at the Bar may help the Law Officers when encountering the wide range of issues they face,Footnote 48 given the range of topics and specialisms it is inevitable that specialist help may be needed, and in Dominic Grieve's time there were about 17 lawyers in the Attorney General's OfficeFootnote 49 (up from two legal assistants during Sir Hartley Shawcross's tenure).Footnote 50 There is also the Government Legal Department (led by the Treasury Solicitor), the Treasury CounselFootnote 51 and the possibility of drawing on other external advice (the Attorney-General maintains a panel of junior counsel, currently numbering some 400, who departments call on to undertake civil work; departments may also use QCs if signed off by the Attorney-General).

Similarly, the Lord Chancellor in an Inner Temple Lecture has said that the ‘historic role as legal advisers to Parliament has been somewhat supplanted by the Clerks and Speaker's Counsel… On very rare occasions in recent history have the Law Officers provided impartial advice to the House, which was the purpose of their medieval writ to the Lords’,Footnote 52 the last example cited being ‘non-partisan advice to the House on picketing’ in the early 1980s. The reason for the limited instances was the ‘increasing sense of conflict’ between their parliamentary and governmental roles, according to Buckland.Footnote 53 Harriet Harman (Solicitor-General, June 2001–May 2005) ascribed this conflict to the undermining of ‘the confidentiality of the lawyer/client relationship between the Law Officers and the Government’, in a written parliamentary answer in which she also listed the three areas covered by the Law Officers’ role as legal advisors to Parliament: ‘First, the constitution and conduct of proceedings in the House, including questions of parliamentary privilege. Secondly, the conduct and discipline of Members. Thirdly, the meaning and effect of proposed legislation’.Footnote 54

(c) The Parliamentary functions

As ministers, the Attorney-General and the Solicitor-General are accountable to Parliament. As with other departments, there are Attorney-General's questions every six weeks (usually on a Thursday, preceding questions to the Leader of the House). With regard to legislation, not only do the Law Officers advise government and Parliament on legislation by other ministers (and private members), but they also oversee the passage of legislation in their areas. While the Attorney-General often takes responsibility for uncontroversial consolidation bills, statute law repeal bills, technical administration of justice bills and other uncontroversial bills which start their passage in the House of Lords, they are not the only Bills that the Attorney may be involved with. Looking through Hansard shows that the Attorney-General moved the second reading of over 150 Bills between 1800 and 2020 but was involved with many more, either responding to private members bills or being part of a Bill team led by others. A number of these may only have needed a very short debate (on occasion taking up less than a column in Hansard),Footnote 55 but others are on somewhat bigger and more heated topics. When Sir Thomas Inskip, then Solicitor-General, moved the second reading of the Criminal Justice Bill 1923 he noted that it ‘has been the fortune, or misfortune, of my right hon. Friend the Attorney-General and myself to be associated with one or two rather controversial Bills in connection with legal matters in the course of this Session’ but rightly expected that Bill, based on a number of non-partisan commissions, to be less controversial.Footnote 56 Other examples include: that ‘Sir Rufus Isaacs, a prodigious speaker in the House, guided the Parliament Act 1911, the Official Secrets Act 1911 and the Government of Ireland Act 1914 through Parliament’ (as noted by Robert Buckland, although Sir Rufus did so as part of a team);Footnote 57 the introduction of a number of pieces of liberating or restricting trade union legislation;Footnote 58 and the response to the declaration of independence by Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 59

Outside the ministerial parliamentary role, there is the advisory role mentioned above. While it is, in Sir Geoffrey Cox's words, now ‘very rare for the Attorney General to appear to answer questions in the House on matters of law’ he did so during the discussion on the Withdrawal Agreement ‘so that Opposition and Government Members can have a full, frank and thorough opportunity to ask me, as the Government's chief legal adviser and as an adviser to the House on constitutional and legal matters, what our legal position is’.Footnote 60 Some decades earlier, Sir Hartley Shawcross recounts ‘Every evening after court hours they [the Attorney and Solicitor General] are to be found in their rooms in the House of Commons ready to go into the Chamber if any need for their attendance arises’.Footnote 61 Previously, the Attorney-General would be a member of the House of Commons’ Committee of Privileges,Footnote 62 but since 1995 the Standing Orders of the House have said that Law Officers, if members of the Commons, may attend, take part in deliberations, receive committee or sub-committee papers ‘and may give such other assistance to the committee or sub-committee as may be appropriate, but shall not vote or make any motion or move any amendment’Footnote 63 and accordingly their attendance (as non-members) is less.Footnote 64

(d) Litigatory

The Attorney-General's litigatory role both serves to protect the public interest (it being a key aspect of the guardianship of the public interest vested in the Attorney) and brings a risk of conflict of interest. It spans from ministerial superintendence to personal appearance in court and – as with some other facets of the role – has been subject to various controversies and change over the years. With regard to criminal prosecutions, a mid-nineteenth commentary, written before the advent of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP),Footnote 65 noted that

[e]xcept in cases of high treason or sedition, it is no part of the official duty of the Attorney-General to institute a prosecution, although it frequently happens that he does so when a crime of more than usual magnitude has been committed, or when the offense is one in which the public takes an unusual degree of interest.Footnote 66

Over 100 years later, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) was established under the DPP,Footnote 67 creating more comprehensive independence from the police but also in turn from the Law Officers. While the Attorney-General has superintendence of the CPS, ‘scrutinising how the CPS is run, to ensure we use public money properly’ in the words of Max Hill, DPP 2018-, the Attorney-General ‘is not involved in the decisions that we take in the vast majority of our cases’.Footnote 68 As Dominic Grieve put it in 2013 ‘I continue to superintend the work of the DPP and the CPS and I am answerable to Parliament for their work – I do not control or direct their daily work’.Footnote 69 This stance is a result of the Protocol between the Attorney-General and the Prosecuting Departments, introduced in 2009,Footnote 70 which held that ‘The Attorney General is responsible for safeguarding the independence of prosecutors in taking prosecution decisions’ (at para 2.4)Footnote 71 and that

Other than in the exceptional cases… decisions to prosecute or not to prosecute are taken entirely by the prosecutors. The Attorney General will not seek to give a direction in an individual case save very exceptionally where necessary to safeguard national security. (at para 4.3)

This contrasts with the situation in the mid-twentieth century when Sir Hartley Shawcross told the House of Commons in an adjournment debate:

My hon. and learned Friend then asked me how I direct myself in deciding whether or not to prosecute in a particular case. That is a very wide subject indeed, but there is only one consideration which is altogether excluded, and that is the repercussion of a given decision upon my personal or my party's or the Government's political fortunes; that is a consideration which never enters into account.Footnote 72

One reason for this change was the controversy surrounding Lord Goldsmith and his involvement in the halting of a fraud investigation into BAE (which was formally halted by the Director of the Serious Fraud Office). He had intervened through his superintendence of the Serious Fraud Office and had canvassed ministers’ views on the public interest, but the Director had ultimately decided that it was not in the public interest to pursue a particular investigation. While the propriety of the decision was upheld by the House of Lords,Footnote 73 the concern, and others concerning the cash for honours scandal, led to the development of the protocol above (rather than pursuing more fundamental reform proposed by the 2007 Green Paper).Footnote 74 The protocol also limits the more direct power to stop criminal trials if it is judged to be in the public interest to do so by entering a nolle prosequi, so the description of the power by Viscount Dilhorne, that the Attorney:

merely has to sign a piece of paper saying that he does not wish the prosecution to continue. He need not give any reasons. He can direct the institution of a prosecution and direct the Director of Public Prosecutions to take over the conduct of any criminal proceedings and he may tell him to offer no evidence. In the exercise of these powers he is not subject to direction by his ministerial colleagues or to control and supervision by the courts is no longer fully the case.Footnote 75

The Attorney-General does, however, still have to provide consent to certain prosecutions by statute, and does so in a quasi-judicial way considering the public interest.Footnote 76 A 2018 CPS document lists 42 Acts where the Attorney-General's consent is required (and a further ten where consent by the Attorney-General or another, such as the DPP, the Court, or the Secretary of State, is required).Footnote 77 These exceptional cases are broadly said to relate to the public interest in restraining prosecutions in particularly sensitive areas, ranging from obscenity to trade unionism and official secrets to the proper reporting of committal proceedingsFootnote 78 as well as matters of national securityFootnote 79 and diplomacy.Footnote 80 However, why the Attorney's consent is needed for some and not other similar cases was described in 1984 by Lord Simon of Glaisdale as ‘an absolute hotch-potch’ with no identifiable ‘animating principle’ despite his asking officials for one over many years.Footnote 81 The situation is further clouded by there being 72 Acts where the requirement for consent is vested in the DPP.

Although the Attorney-General's role in prosecutions is limited, there are many other litigatory responsibilities and possibilities often deriving from the guardianship of the public interest, including: references to the Court of Appeal regarding points of law and regarding unduly lenient sentences under s 36 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988; involvement in criminal appeals; applications for contempt; actions to protect charities; actions to protect the justice system against vexatious litigants; consenting or withholding consent to relator actions (where individuals seek to bring civil proceedings to enforce a public law right); as well as defences to claims brought against government departments; being the default defendant or claimant in claims against or by the government where no appropriate department is evident;Footnote 82 and representing the UK government at the European Court of Human Rights (and formerly the Court of Justice of the European Union).

Personal appearance in court is now down to individual preference.Footnote 83 While the Law Officers were based in the Royal Courts of Justice for over 90 years from 1893, following the ending of their combining private practice with their official role (rooms having been made available there then as they were no longer able to use the chambers from which they formerly practised),Footnote 84 attendance in court was diminishing as the ministerial role increased. Cornish et al note that ‘In 1872 the Chancellor of the Exchequer claimed that advising on and conducting government prosecutions was the law officers’ most important duty, but his view was out of date’.Footnote 85 To be more precise, the Chancellor said the primary object of a Law Officer of the Crown was:

to defend it in all the law suits which, owing to the vast quantity of property they administer and the immense number of transactions in which they are engaged, they are concerned in, or in all the suits or prosecutions they may think it necessary to institute.Footnote 86

In 1966, Elwyn Jones said ‘[whether] a Law Officer appears personally in any case is a matter for my judgment’ with the ‘paramount consideration’ being the public importance of the matter, taking account, in the words of the questioner ‘of the additional and heavy duties in Parliament and particularly… duties in law reform’.Footnote 87 Come 1997, Lord Falconer, during debate on the Law Officers Bill, noted that the Law Officers, despite being salaried for non-contentious work since the late nineteenth century, received extra remuneration when they appeared in court for the Government until ‘thanks to the negotiating skills of Mr Hartley Shawcross (as he then was), that right was negotiated away in return for a bigger salary’.Footnote 88 He went on to ‘imagine that there is no connection between that negotiation taking place and the fact that the appearances of the Law Officers in court have substantially declined since then’.Footnote 89 An analysis of reported court appearances by Attorney-Generals since the Second World War does indeed show a decline, though to be fair it did not immediately follow the change in remuneration arrangements. Indeed, the Dictionary of National Biography entry for Sir Peter Rawlinson states that he ‘insisted… on leading for the Crown in more criminal trials than any of his predecessors had done, on every circuit but the Welsh’.Footnote 90

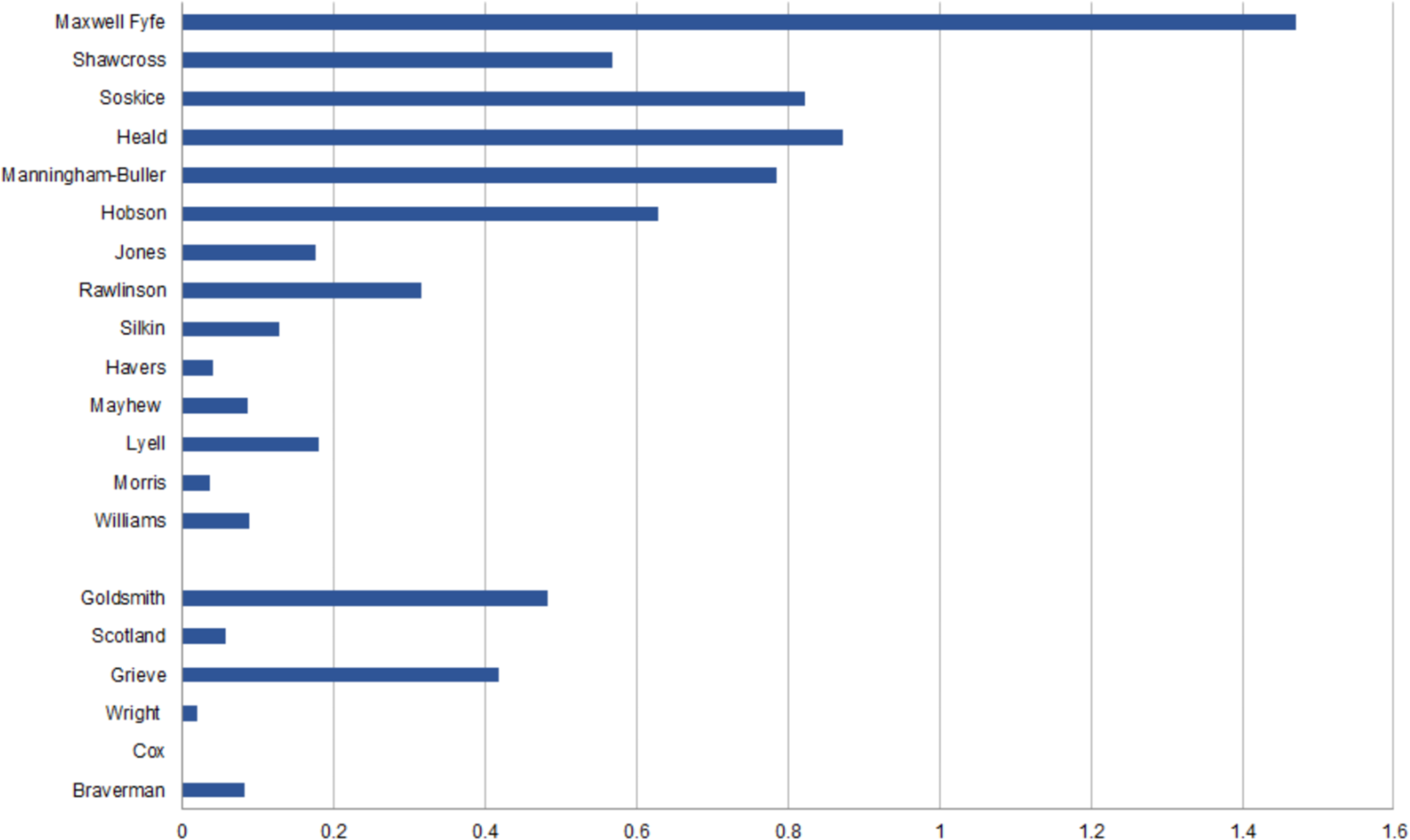

Of the 20 Attorney-Generals appointed since Maxwell-Fyfe in May 1945 to Suella Braverman in February 2020, searches on WestlawFootnote 91 show an average of 14.3 appearances per Attorney-General, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 73. Tenure in office would affect the number of appearances (Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller's 73 appearances being over his nearly seven-and-three-quarter years in office whereas Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe's term was only two months, during which time he appeared three times) and so the chart below (Figure 3) shows the number of appearances divided by the number of months in office.

Figure 3. Chart showing average appearances in court during attorney-generalship

A steep reduction over the years is clearly evident and even the spikes caused by Lord Goldsmith's and Dominic Grieve's more active approaches are considerably below the likes of Sir Hartley Shawcross and his four immediate successors.

A divide could be made between taking action as guardian of the public interest (such as Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller's amicus curiae role in the leading charity case of Inland Revenue Commissioners v Baddeley and Others)Footnote 92 and appearing for the government (such as Elwyn Jones defending the negligence appeal in Dorset Yacht Co Ltd v Home Office).Footnote 93 A response to a Freedom of Information Act request to the Attorney General's Office takes such an approach when listing Dominic Grieve (and Edward Garnier's) activity in their first 18 months and includes actions for contempt and unduly lenient sentences among the former,Footnote 94 which comprise the majority of his appearances throughout his tenure. Lord Woolf, however, in his Hamlyn lectures, has remarked ‘that in controversial cases involving the Government it seemed virtually impossible for the public or the media to identify when the Attorney-General was wearing his guardian of the public interest hat rather than his governmental hat’.Footnote 95

It should be emphasised that, even with the greater attenders, there are many cases involving the Attorney-General where the Attorney does not attend in person: while Dominic Grieve is reported above as attending court around 20 times, there were around 200 Attorney-General's References alone during his period of office.Footnote 96 The choice to appear in person is greatly limited by the other demands of the job but where possible it may be driven by a wish to keep one's hand in, or as Grieve put it ‘to maintain [his] professional presence within the bar’,Footnote 97 or to mark the momentousness of a case, or for perceived political expediency. Jeremy Wright's one case was at the time billed as the one of the biggest constitutional cases of recent times,Footnote 98 and was one where he recognised his limitations:

I was a criminal lawyer, that's what I did. There were lots more experienced constitutional lawyers around for the government to hire than me and it would have been absolute folly if what I had decided to do, with my background, is conduct that whole case myself. So what we settled on was a compromise. I presented the case to start with and then we handed over to others to conduct the rest of it. That, I think, was the right thing to do.Footnote 99

The ‘others’ he referred to were James Eadie QC, the First Treasury Counsel since 2009, Lord Keen QC, the Advocate-General for Scotland, Jason Coppel QC, a leading public law QC, and three juniors. In the judgment, it is notable that the Attorney-General's submissions are mentioned only once,Footnote 100 whereas James Eadie is mentioned 16 times. While the government lost the case, the Attorney-General's reputation was arguably enhanced by his recognition of his limitations and his performance. The same cannot be said for Sir Michael Havers or, even more recently, Suella Braverman. The trial of the Yorkshire Ripper was one of the highest profile criminal trials of the twentieth century and as Attorney-General, Sir Michael Havers intervened, subordinating the QC and junior appointed by the DPP. Sir Michael wished to accept the guilty to manslaughter plea despite the arguments of the rest of the team but failed to persuade the judge at a directions hearing who, at the end of the lengthy hearing, asked him to reconsider (the question of manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility being a jury matter). This led Sir Michael to the conclusion that while he would cross-examine Peter Sutcliffe, when it came to challenging the psychiatric evidence (which he had shown such willingness to accept in the directions hearing) that would have to be conducted by Harry Ognall QC. Reflecting on the case, Ognall described Havers’ cross-examination of the defendant as ‘not so much as a confrontation between the senior law officer of the Crown and the (then) most prolific killer of our lifetimes, but more of a civilised dialogue at an academic level between equals’ and that while Sir Michael Havers was ‘a charming, intelligent and highly experienced advocate’ the exchanges ‘did little to throw light on the issue for the jury’.Footnote 101 Suella Braverman's argument, in her unsuccessful referral to the Court of Appeal for unduly lenient sentencing of the killers of a police constable – that the judge should have departed from the guidelines when sentencing – were described by the judges as ‘unconventional’ and that it was ‘regrettable that, in advancing that submission, the structure and ambit of the guideline were not addressed. Nor was any sufficient explanation given why it is contended that the judge was not merely entitled to depart from the guideline but positively required to do so’.Footnote 102 While both cases may have seemed to be politically useful cases to be associated with, the outcomes were politically and professionally damaging.

(e) Ex officio

Among the other sundry roles and responsibilities of the Attorney-General, he or she is the titular head or ex officio leader of the Bar in England and Wales. This was not always the case. An order of 1814 gave the Attorney-General (and deputy) precedence over all the King's Sarjeants without exception (the Premier Serjeant and the Antient Serjeant previously taking precedence).Footnote 103 As Leader, questions of professional conduct and etiquette relating to the Bar would fall to the Attorney-General to deal with but as Sir Elwyn Jones recorded in 1969 ‘for a very long time now [that] has been discharged by the Bar Council’Footnote 104 (although the Law Officers would be consulted) and as Lord Hailsham remarked in 1979 ‘much of the glory has departed and now rests on the corporate personality of the Senate and Bar Council’.Footnote 105

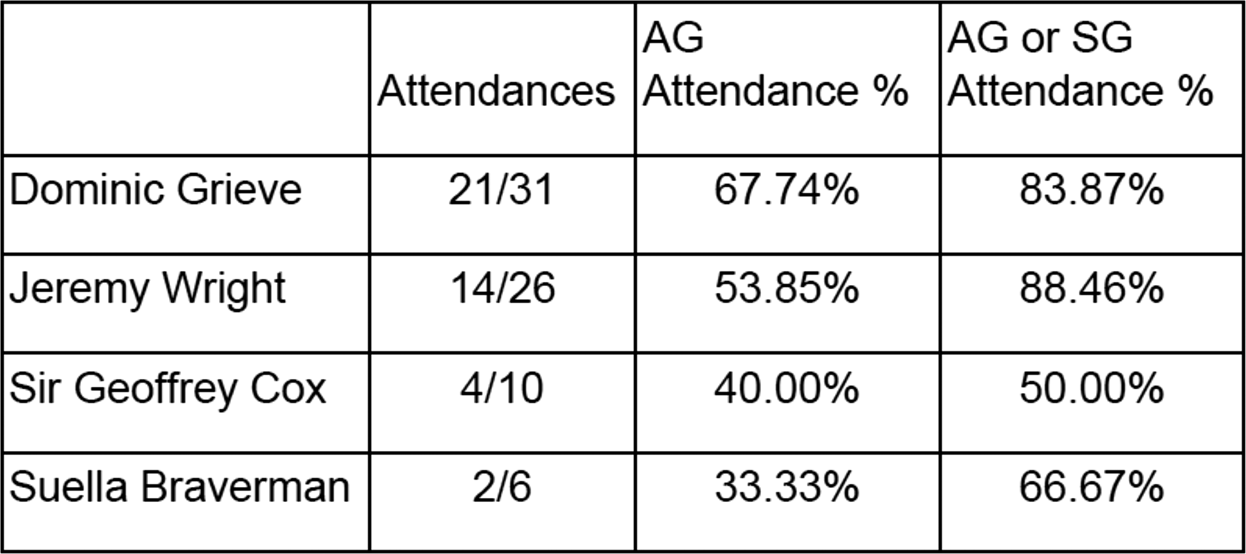

The Attorney-General and Solicitor-General are ex officio members of the Bar Council (as is the DPP),Footnote 106 but it is chaired by an elected Chair (who currently may serve a maximum of two one-year terms).Footnote 107 Among the past Chairs, two from the early-mid 1990s went on to become twenty-first century Attorney-Generals in the Blair Administration (Lord Williams of Mostyn and Peter (later Lord) Goldsmith) and two in the 1950s and 1970s respectively had previously been Attorney-General (Sir Hartley Shawcross and Sir Peter Rawlinson). A review of Bar Council minutes from 2010–2020Footnote 108 shows variable attendance at Bar Council meetings by the two Law Officers, but always at or above 50% of meetings between them (Figure 4). Dominic Grieve, as with court appearances, leads the way with over twice as many attendances, pro rata, as Suella Braverman (despite the meetings having gone virtual, after her first attendance, due to the Covid-19 pandemic).

Figure 4. Law Officer attendance at Bar Council meetings

The Attorney-General was also formerly one of the ex officio Church Commissioners from the inception of the commission in 1947Footnote 109 until 1999 saw wider reforms to its membership (reducing ex officio members to the current number of six, including the Prime Minister and Lord Chancellor),Footnote 110 and an ex officio trustee of the British Museum from 1753Footnote 111 until the British Museum Act 1963 reformed the Trustee board.Footnote 112 A more recent addition to the role is that, following devolution, the Attorney-General is also ex officio Advocate-General for Northern IrelandFootnote 113 (in place of being Attorney-General for Northern Ireland as was the case between direct rule starting in 1972 through to the devolution of justice in 2010).Footnote 114 Whereas devolution matters and advice on law to the UK government when it comes to Scotland are the province of the discrete Advocate-General for Scotland, non-devolved matters for Northern Ireland fall to the Attorney-General in the conjoined role as Advocate-General for Northern Ireland and raise similar issues to those considered in the advisory and litigatory sections above.

3. Brown-era reform

The characteristics, preferences, behaviour and roles of the Attorney-Generals have varied over the years and different incumbents have faced different controversies. Following the issue of the Iraq War advice and the BAe bribery scandal in the mid-2000s, and as part of a suite of constitutional reform proposals within the Governance of Britain Green Paper,Footnote 115 the Government consulted on reforming the role of the Attorney-General.Footnote 116 Radical change was not supported then, although limited legislative constraints were intended by the Government (abolishing the general power to enter a nolle prosequi while gaining a statutory power to halt prosecutions on grounds of national security subject to a Parliamentary reporting safeguard; reducing the number of cases where Attorney-General's consent is needed; and bolstering the independence of the prosecuting authorities by providing for fixed-term appointments for their directors).Footnote 117 Splitting the functions was resisted as the range of roles, while potentially giving rise to an appearance of a conflict (and may at times be difficult to manage) was seen not as a weakness but a strength, as status as a ‘senior practising lawyer’ aids understanding of the prosecuting authorities, helps to guide the authorities’ strategic direction, and – combined with the status as a senior minister – helps to ensure the government respects and upholds the rule of law, particularly following the change to the Lord Chancellorship.Footnote 118 While the legislative proposals fell to the side, and were omitted from the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010, a protocol was (as mentioned above) introduced to underline the general independence of the prosecuting authorities.Footnote 119

4. Approaching the fork in the road

Over a dozen years since then – and a few years longer since the similarly multi-faceted Lord Chancellor lost his judicial role in part to the Lord Chief Justice, ceased to have to have a legal qualification and became the Secretary of State for JusticeFootnote 120 – the background has changed. Of Baroness Scotland's five successors as Attorney-General, as illustrated in Figure 5, four had been a QC for under two years before being appointed to the post, indeed three of them took silk contemporaneously with being appointed as a Law Officer (Solicitor-General in the case of Michael Ellis and as Attorney-General in the cases of Jeremy Wright and Suella Braverman) whereas the average twentieth century Attorney-General was KC/QC for a decade before taking the role (and none had such a short period before appointment). In the case of Wright and Braverman, they are in the bottom 20% of post-World War Two Attorney-Generals in terms of service at the Bar (post call) before being elected to Parliament and none had a shorter period between being called to the Bar and becoming Attorney-General (whereas Michael Ellis is closer to average). As mentioned in the Ministerial section above, those three could also be said to have a more politically-charged ministerial past than many, although prior-ministerial office seems to be a trend since Havers in the early 1980s.

Figure 5. Chart showing twentieth and twenty-first century Attorney-Generals and the gap between becoming a QC and being appointed Attorney-General

One reason for a comparative lack of experience among recent Attorney-Generals is the decline in the number of barristers in the House of Commons – and the increasing pressure against members having second jobs may compound that in the future. Between 1997 and 2015, barristers made up around 5% of the House of Commons (3.6% of Labour MPs and 7.2% of Conservatives) whereas between 1951 and the 1974, long before the change to Parliamentary hours impeded working at the Bar in the morning and Parliament later in the afternoon,Footnote 121 there were proportionally three times as many (see Figure 6).Footnote 122 A reformed House of Lords may not allow a way-in for an experienced barrister as was the case with Lord Goldsmith, Lord Williams of Mostyn and Baroness Scotland. With a judicial career all but closed off, and a limited ability and potentially pending inability to practise at the Bar and serve as an MP, the ambitious barrister MP is more likely to look at a more political career rather than be the semi-detached defender of the rule of the law, but that will only create greater tensions within the multi-faceted role. Past Attorney-Generals have included the politically ambitious, such as Perceval and Rufus Issacs but, as illustrated above, that has not been the norm. If that is the future, as well as seemingly the present, then it may be more appropriate now to reconfigure the role. However, that need not see the complete severing of all the ministerial, advisory, parliamentary, litigatory and ex officio functions.

Figure 6. Chart showing proportion of the House of Commons who were barristers by national party 1951–2015

5. The future

The role of the Attorney-General, and the Solicitor-General, has evolved over many centuries. The ministerial function has increased markedly (particularly over recent decades), the parliamentary has been pared back towards that of an ordinary minister, the litigatory has been limited by constitutional appropriateness and logistics (as the size of government, the amount of litigation and the role in government increased), and ex officio roles have emerged and fallen away as times have changed. As the intensity of the functions and the delegation of aspects of them have increased, the balance of the role has changed; and as the level of legal experience has decreased and the political nature has come more to the fore, a repositioning of the role may be necessary.

All polities are different but in the Westminster model the ministerial and the parliamentary are intertwined. Across the world, the role of Attorney-General varies. They are the Cabinet level head of the department of justice (by name or by role) and having some responsibility for prosecutions and other litigation in, for example, Australia, Canada, the US, Kenya, Nigeria and New Zealand, ‘non-ministerial’ legal advisors in, among others, Israel, India and Ireland (but able to attend Cabinet and/or Parliament) and are just the public prosecutor in Malta (the legal advice role having then been ceded to the State Advocate in December 2019 and the political role having ended in 1921). More locally, it is not particularly clear why the Government's chief legal advisor and officer should necessarily be a member of either the House of Commons or House of Lords (the Lord Advocate in Scotland and Counsel-General in Wales may be a member of the devolved Parliaments but need not be, whereas the Attorney-General for Northern Ireland may not be a member of the Northern Ireland Assembly or the House of Commons although all may be accountable to their legislatures).Footnote 123 Adopting such an approach may help expand candidates for the post but does not necessarily inure them to political controversy.Footnote 124 It is in any case a fiction to see the Attorney-General (and the Solicitor-General) as the only advisors. It is similarly a fiction to say that someone appointed QC after the day of their appointment as Attorney-General, and conceivably with experience which would debar them from being Attorney-General for Northern Ireland (as that has a statutory requirement of ten years’ standing),Footnote 125 is the head of the profession (albeit ex officio). As much of the litigation is undertaken by others and advice provided by others, the role, if its incumbents are to be more political and less experienced, could be more formally delineated, insulating aspects of the legal and political, while retaining some of its uniqueness.

The value of having a minister involved in the provision of legal advice and overseeing the political policy and the legal aspects is not diminished through spinning some duties off to officials. Rather than seeing the top ministerial legal officer being the chief provider of advice and lead litigator, the minister could be (as to large extent is the case) the procurer of legal advice and advocacy and act as a link and buffer, as was and is case with the Lord Chancellor. When the Lord Chancellor ceased to be the apex of the three branches of government (a senior Cabinet member, Speaker of the House of the Lords and member and administrator of the judiciary), the role became that of a more ordinary (and ordinarily paid) minister, but one which while no longer needing legal experience (if the Prime Minister considers other experience appropriate) bears a statutory duty to uphold the rule of law and retains some oversight of the judiciary (having ceded some powers to, and in some cases working alongside, the Lord Chief Justice). Like the Lord Chancellorship, such a duty could be expressly included (although the value has been questioned), but currently unlike it, legal experience of a certain amount could, however, be required for the government Law Officer(s) so as to be able to obtain, interpret and share the legal advice (more like a solicitor than an attorney) and to aid oversight of the independent agencies. Not all aspects of the public interest role would thus be delegated but the DPP could take on a greater share of approving prosecutions and intervening in the public interest. On the civil side, more quasi-judicial, independent and leadership aspects could devolve to a possibly renamed Treasury Solicitor; with more operational responsibility devolved to the public servants, it may be the case, as in Australia and New Zealand, that there is no need for both an Attorney-General and Solicitor-General as politicians (the Solicitor-General there being a public servant). If so, the twenty-first century trend that the Solicitor-General in England and Wales is no longer the apprentice or Attorney-in-waiting (as per Figure 2) means that any reallocation of titles would not affect the pipeline of candidates for the more political role. If there is a reversion to less political and more experienced Law Officers such reforms may not be needed, but the choices of recent Prime Ministers suggest the path may now be set.