Social scientific studies of relations between the police, the state, and society have a long and rich tradition within the United States and the United Kingdom, and the last several decades have witnessed the growth of a comparative policing literature (Reference CainCain 1993; Reference Bayley and MawbyBayley 1999; Reference Mawby and MawbyMawby 1999; Reference Caparini, Marenin, Caparini and MareninCaparini & Marenin 2004). We contribute to this literature by examining the prevalence, patterns, and consequences of public experiences of police violence and police corruption in contemporary Russia. Scholars, journalists, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have suggested that police violence and corruption have become rampant in Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991. They have documented the forms that police misconduct takes, proposed explanations for why it has grown more frequent, and considered possible measures that might be taken to combat it. But these accounts rely largely on anecdotes, case studies, official data, localized investigations, and interviews rather than standard social science methods, and they do not derive broader theoretical insights from the Russian case. We seek to advance both empirical and theoretical understanding of police misconduct in Russia by analyzing data from six large sample surveys and from nine focus groups.

We address four empirical questions: (1) How widespread are public encounters with police violence and police corruption in Russia? (2) To what extent does exposure to these two forms of police misconduct vary by social and economic characteristics? (3) How do Russians perceive the police, the courts, and the use of violent methods by the police? (4) How, if at all, do experiences of police misconduct affect these perceptions? Given the quality of our data, our empirical findings provide a useful benchmark against which future social scientific studies of police misconduct in Russia can be measured.

Our empirical findings have three broader theoretical implications for social and political perspectives on police misconduct. Most important, the Russian pattern of police misconduct suggests a model of policing that has not been formally identified in the comparative policing literature: predatory policing. Policing can best be described as predatory where police activities are mainly (not to say exclusively) devoted to the personal enrichment and self-preservation of the police themselves rather than the protection of the public or the systematic repression of subordinate groups. No police force in the world is completely free of corruption and violent abuse by officers in its ranks. Under predatory policing both forms of misconduct are not only widespread—the rule rather than the exception—but they are also motivated primarily by the interests of the police themselves, not the interests of other elites.

Second, by analyzing how police misconduct affects attitudes toward the police and the courts in Russia, we assess whether findings from United States–based research on these topics can be generalized to a very different national context. Russia differs from the United States in several key respects. Russia's police are more centralized and less accountable to the public. Some scholars argue that cultural traditions and Soviet-era experiences conspire to undermine perceptions of individual rights, belief in the rule of law, and trust in legal institutions. If so, low trust in the police could be based on long-standing cultural norms, not direct individual experiences of police misconduct. If individual encounters with police violence and corruption erode trust in legal institutions in Russia, despite Russia's distinctive cultural and institutional context, then U.S. patterns may be generalizable to other widely diverging institutional and cultural contexts.

Finally, the extent and effects of police misconduct in Russia draw our attention to the important but often neglected role of police reform in the process of democratic transition. With the exception of specialists on comparative policing, the vast majority of scholars analyzing transitions from authoritarian to democratic rule focus on reforms of political institutions, the economy, and legal institutions such as constitutions, courts, bodies of law, and judicial procedures. While changes in these realms are clearly integral to democratic transition, another essential condition for its success is that public institutions—especially those, such as the police, with access to the means of violence—serve rather than threaten the public. Our findings suggest that regardless of progress on other fronts, police misconduct undermines democracy in Russia. Scholarly theories of democratic transition should devote more attention to the role of the police and other public institutions. So should policy makers, because an undemocratic police force is a potential source of instability and an ineffective ally in the struggle against global organized crime and terrorist networks.

Before proceeding, we need to clarify what we mean by “public experiences of police violence and police corruption.” We specifically refer to public experiences to highlight our focus on personal encounters with the police that members of the general public (including both citizens and noncitizens) identify as involving violence or corruption by the police officers and on the relationship between these encounters and broader public perceptions of the police and Russia's legal institutions. We define police violence as any act on the part of a police officer designed to inflict severe pain or suffering on the part of the victim, including beating with fists, feet, or instruments, and all forms of physical torture. Russian and international law generally prohibit such acts (Human Rights Watch 1999). Police corruption is a broad concept encompassing many behaviors and activities involving the illegal use of police authority for personal gain. However, our empirical analysis deals solely with corrupt activities that directly victimize individual members of the public: for example, bribe-seeking, extortion, shakedowns, and other activities whereby police officers use their authority to extract money, goods, or services from individuals. Because these corrupt actions always involve a victim in a very immediate sense, they can be studied using the methods and data at our disposal. Other forms of corruption such as collusion with criminals, kickbacks, cover-ups, and trafficking in contraband certainly wreak harm on the public, but they often take place completely outside of public view and therefore cannot be studied using general population surveys and focus groups.

Public experiences of police violence and corruption represent only one aspect of a complex phenomenon. A complete account of police misconduct would require analysis of a broader range of corrupt activities (not limited to those directly experienced by members of the general public), attempts to measure the actual prevalence of different forms of police misconduct, and examination of how the police organize, carry out, and perceive acts of violence and corruption in their ranks. But these topics are beyond the scope of our study. While public experiences are only one aspect of police misconduct, they can be readily studied using standard methods and, as we find, they matter a great deal: they undermine trust in the police and legal institutions and foster the widespread perception that the Russian police are not so much protectors of the public or of the state as they are predators on society.

Theoretical Context

Predatory Policing

Reference WeitzerWeitzer (1995: Ch. 1; see also Reference MareninMarenin 1985) describes two basic theoretical models of the role of the police. Policing in the United States and in most developed democracies conforms by and large to a “functionalist” model, where the police provide services, enforce the law, and preserve order in the general interest. Policing in authoritarian societies and those with polarized social structures tends to conform to a “divided society” model consistent with conflict theory: the police mainly protect the interest of dominant elites and suppress subordinate groups such as racial/ethnic minorities, the poor, or the political opposition. Of course, in any country frequent exceptions to the predominant model occur: police misconduct takes place where the functionalist model prevails, and the police occasionally solve crimes and arrest criminals where the divided society model prevails. The issue is: which model best typifies the performance of the police in a given national context? Among the distinctive characteristics of divided society policing are systematic bias of the police against subordinate groups, strong identification of the police with the ruling regime, and “polarized communal relations with the police, with the dominant group as a champion of the police and the subordinate group largely estranged from the police” (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 1995:5).

At first glance, the reportedly widespread police misconduct in Russia appears to conform to the divided society model. Since Russia became an independent state in late 1991, the police have suppressed real or perceived opposition and have persecuted ethnic minorities and immigrants (Reference Shelley and MawbyShelley 1999; Reference Robertson, Caparini and MareninRobertson 2004). These types of actions have persisted in recent years (Amnesty International 2006; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2007). But we propose that Russia's police may correspond more closely to a third model: predatory policing.

Policing is best described as predatory to the extent that police officers prey on their society by using their positions to extract rents in the form of money, goods, or services from individual members of the public.Footnote 1 They apply violence both as a direct means of extracting these rents and in order to satisfy occasional demands by officials to assist in oppressing opposition groups or to give the appearance of solving criminal cases, thereby preserving their access to opportunities for rent extraction. Predatory policing obviously departs from the functionalist model, where, with some exceptions, the police enforce the law and protect the public.Footnote 2 But it also diverges from divided society policing in three key respects: (1) members of the public are just as or more likely to personally experience police corruption as they are to experience police violence; (2) all groups experience significant levels of police misconduct, even if some groups are disproportionately exposed; and (3) even if elites occasionally deploy the police for political purposes, most instances of police misconduct advance the material interests and self-preservation of the police themselves rather than suppress subordinate groups.

Our distinction between predatory and divided society policing draws attention to the fact that similar forms of police misconduct—violence and corruption—can stem from two different sets of interests: the political interests of elites in preserving their power and the individual material interests of the police themselves. These sets of interests are not necessarily incompatible. Indeed, they appear to operate hand-in-hand in many societies characterized by highly dysfunctional police forces. Accounts of undemocratic, unprofessional, violent, and corrupt policing in countries such as Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil (Reference MorrisMorris 1991; Reference Chevigny and MendezChevigny 1999; Reference Botelo and RiveraBotelo & Rivera 2000; Reference Gomez-CespedesGomez-Cespedes 1999; Reference HintonHinton 2005), Nigeria (Reference IgbinoviaIgbinovia 1985), and other former European colonies (Reference Cole and MawbyCole 1999), describe many predatory police practices. But these practices are closely intertwined with politicized practices involving the systematic suppression of subordinate groups.

Predatory behavior by the police in these countries is thus linked, perhaps inextricably, to their role serving the political interests of particular regimes or officials. The high levels of political conflict and violence that typify these societies make it difficult to disentangle politically motivated from personally motivated police misconduct, and this may explain why observers have not analytically distinguished these two forms of police misconduct. In contrast, since the early 1990s there has been no opposition or overt political challenge to the regime in Russia, apart from the geographically contained separatist conflict in Chechnya. Thus Russia is a case where predatory policing could be clearly predominant. As such, it can help us refine the distinction between predatory policing and divided society policing, develop a methodological approach for distinguishing empirically between the two models, and understand the conditions that produce predatory policing independently of overt political manipulation of the police by elites.

But how can we ascertain empirically whether predatory policing predominates in Russia? Based on our conceptual distinction between predatory policing and divided society policing, three questions identify which model applies to a particular national context where police misconduct is extensive: (1) How common are public experiences of corruption, relative to experiences of violence? (2) How insulated from police misconduct are members of the ethnic majority and socioeconomic elite? (3) To what extent are acts of police misconduct motivated by personal gain of the police rather than political objectives? A greater prevalence of encounters with corruption, less insulation of particular ethnic and socioeconomic groups from police misconduct, and the identification of personal gain rather than political objectives as the main motive for police misconduct all point toward predatory policing rather than divided society policing. These questions may be difficult to answer for the countries of Latin America and Africa. But our data provide answers to all three questions with respect to Russia, and in each case they are consistent with predatory policing.

Generalizing Findings From the United States

Most political and legal theorists would agree that “the ability of the police and other government officials to enforce the law depend[s] upon public satisfaction with, confidence in, and trust of legal authorities” (Reference TylerTyler 1984:51; see also Reference TylerTyler 1990). In turn, a legion of studies have shown that negative personal experiences with the police tend to lower confidence in the police in the United States (e.g., Reference Smith and HawkinsSmith & Hawkins 1973; Reference Scaglion and CondonScaglion & Condon 1980; Reference TylerTyler 1990; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 2004) and in Canada (Reference KoenigKoenig 1980; Reference WortleyWortley et al. 1997). But it is unclear whether the relationship observed in the United States also obtains in other national contexts with radically different police institutions and legal culture. Moreover, even in the United States few studies examine whether negative experiences with the police affect views toward other legal institutions such as the courts (Reference TylerTyler 1990).

Russia differs institutionally and culturally from the United States in ways that make it doubtful that the United States–based findings apply. Russian police institutions are far more centralized than the U.S. police, which could mean that Russians' views of the police are closely associated with their views of other federal government institutions rather than their immediate personal experiences. In addition, institutional mechanisms whereby the public can exercise some degree of authority over the police and the courts (such as citizen review boards, elections of sheriffs and judges, or lawsuits seeking redress for police brutality) are essentially lacking in Russia. The absence of formal accountability may make notions of “procedural justice” highly abstract and irrelevant to Russians to begin with.

That would be consistent with a standard explanation for the difficulties of establishing a rule of law in Russia that emphasizes legal culture—more specifically, the lack thereof—in the popular consciousness (Reference Shelley and MawbyShelley 1999). According to this view, a “negative myth” that sees the law as a mere instrument of the powerful predominates in Russian culture (Reference Kurkchiyan, Galligan and KurkchiyanKurkchiyan 2003). Some identify long-standing Russian cultural tradition as the source of deep skepticism regarding the law (Reference McDanielMcDaniel 1996; Reference Newcity, Sachs and PistorNewcity 1997). Others point to Soviet-era experiences. Writing on the eve of the collapse of state socialism, Reference MarkovitsMarkovits (1989) voiced doubts about the prospects for meaningful judicial review in the socialist countries because judges and citizens alike were so accustomed to dependence on the state that they could not perceive themselves as the protectors or bearers of individual rights. A decade later, Reference HendleyHendley (1999) attributed low “demand” for law by the Russian public to decades of witnessing the Communist party use law in purely instrumental fashion and to more recent examples of economic elites doing the same.

Whether rooted in historical traditions or in Soviet-era experiences, a deeply ingrained skepticism toward the law and legal institutions in Russia would seem to rule out any confidence in the police and the courts, whether or not individuals directly experience police misconduct. If predatory policing does prevail in Russia, police misconduct may be so common as to evoke little outrage or surprise on the part of victims. Thus although it seems intuitive that people who personally experience police misconduct will consequently have less confidence in the police and other legal institutions, the unique institutional and cultural context of Russia could weaken the effects of individual experience relative to general cultural norms and attitudes. If Russians perceive police violence and corruption to be the normal state of affairs, those who experience them could be no more likely than others to report low trust in the police and the courts.

Some scholars dispute the claim that Russian views on the rule of law differ from views in other European societies (Reference Gibson, Galligan and KurkchiyanGibson 2003). And even if deep skepticism of legal institutions prevails in Russia, direct individual experiences with police misconduct could still undermine confidence in both the police and the courts. Our survey data contain several measures of attitudes toward the police and the courts. Thus we can readily examine whether experiences of police misconduct influence attitudes toward legal institutions. If personal encounters with police misconduct affect views of the police and the courts in Russia, then the findings from the United States can apply in very different institutional and cultural contexts.

A related issue is whether Russians actually have tolerant attitudes toward police violence. Some scholars argue that Russians are inclined to favor authoritarian rule (Reference McDanielMcDaniel 1996; Reference PipesPipes 2004). Support for a strong hand on the part of the state, coupled with fear of rising crime, may well prompt Russians to advocate harsh police measures. If so, they may view beatings and torture by the police as acceptable practices. In that case, media reports about violent abuses by police—another source of negative views toward the police in the United States (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2002)—may not undermine confidence in the police among Russians and may even bolster their confidence. We do not have direct measures of exposure to reports about police violence in our data, but we do have survey questions and interview materials that let us directly assess whether Russians approve of police violence.

Policing and Democratic Transition

The potentially predatory character of policing in Russia today underlines how essential police reform is to successful democratic transition. Political scientists, sociologists, and economists who study postsocialist transitions tend to emphasize political institutions such as elections, parties, and parliaments and economic changes such as privatization and market reform (e.g., Reference PrzeworskiPrzeworski 1991; Reference CentenoCenteno 1994; Reference FishFish 1995; Reference Shleifer and TreismanShleifer & Treisman 2004). Legal scholars devote due attention to establishing rule of law, but they focus on the formation of new legal institutions and procedures and the use of laws to resolve economic disputes (Reference Sanders and HamiltonSanders & Hamilton 1992; Reference PistorPistor 1996; Reference HendleyHendley 1999; Reference HendleyHendley et al. 1999, Reference Hendley2000; Reference BlackBlack et al. 2000).

The regression of Russia's police force into a predatory institution demonstrates that these political, economic, and legal transformations are only part of the story. The task of establishing government institutions that provide services to the public and protect human rights and individual security is a distinct and equally crucial component of democratic transition, as criminologists and specialists on policing have recently begun to point out (Reference BayleyBayley 2001; Reference Caparini, Marenin, Caparini and MareninCaparini & Marenin 2004; Reference Karstedt and LaFreeKarstedt & LaFree 2006). Establishing a professional, legitimate, and accountable police force is clearly a vital part of this process (Reference Caparini, Marenin, Caparini and MareninCaparini & Marenin 2004). As several studies of Brazil, where the police violence increased following democratization of the political system, have noted, police abuse violates the human and civil rights that democratic institutions are supposed to protect (Reference Caldeira and HolstonCaldeira & Holston 1999; Reference Mitchell and WoodMitchell & Wood 1999). By undermining individual security, it impedes the exercise of citizenship rights; fosters impunity of the powerful; promotes inequalities of power, rights, and wealth; and threatens to delegitimize the entire project of democratization.

According to Bayley, in the 1990s the U.S. government came to appreciate “that security is important to the development of democracy and police are important to the character of that security” (2001:5) and that democratic police forces in other countries were more effective partners in combating international crime rings and other security threats. For these reasons, the promotion of democratic policing is an important foreign policy goal in the United States. In light of Russia's enormous geopolitical and economic power, predatory policing there should be of particular concern to policy makers in the United States. Corrupt and violent police are likely to be complicit in organized crime and even in terrorist activities.Footnote 3 Thus in addition to undermining social order, fostering domestic insecurity, and jeopardizing what remains of Russia's democratic political institutions, predatory policing also threatens international security.

The Police in Russia: Brief Background

The Russian police system is centrally controlled and administered at the federal level (Moscow-Helsinki Group 2005). The centralized structure was inherited from the Soviet police, described by Reference ShelleyShelley (1990, Reference Shelley and Mawby1999). In the 1960s, the Soviet police began to evolve from a very intrusive organization whose main purpose was to safeguard the state and the party into a more professional force that devoted more effort to preserving public safety. However, during the Brezhnev era (1964–1982), growing corruption, which produced several highly publicized scandals involving major political figures, thwarted professionalization. The press freedoms introduced in the late 1980s exposed still more cases of corruption. Meanwhile, crime rates began to soar and organized criminal groups grew emboldened—two trends reinforced by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Center for Strategic and International Studies 1997; Reference Pridemore and BarakPridemore 2000, Reference Pridemore2002; Reference Shelley and SperlingShelley 2000; Reference Gavrilova and PridemoreGavrilova et al. 2003). Recent years have seen some diversifying and decentralizing tendencies, but these have not fundamentally altered the centralized character of Russia's police (Reference Shelley and MawbyShelley 1999; Reference Favarel-Garrigues and Le HuerouFavarel-Garrigues & Le Huerou 2004; Reference Robertson, Caparini and MareninRobertson 2004).

By the time the Soviet Union unraveled, the Russian police were ill-equipped to confront surging crime and needed thorough modernization. But rather than implement systematic, fundamental reforms, the Russian government introduced a confusing series of reorganizations, renamings, and leadership changes. Meanwhile, despite formal laws providing supervisory authority over law enforcement to the Russian legislature, the administrative organ overseeing the police—the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD)—defied any attempts to exercise such authority (Reference Waller, Sachs and PistorWaller 1997). On the street, the police continued to suffer low salaries (exacerbated by inflation), insufficient personnel (in particular, experienced officers and qualified recruits), poor training, outdated communication and transportation equipment, and a lack of computers (Human Rights Watch 1999; Reference Shelley and MawbyShelley 1999; Reference Pridemore and BarakPridemore 2000; Reference Robertson, Caparini and MareninRobertson 2004). These conditions persist, according to a recent Russian study (Moscow-Helsinki Group 2005). Many left the police to pursue more lucrative opportunities in private security firms (Reference Shelley and MawbyShelley 1999, Reference Shelley and Sperling2000).

Police Violence and Corruption: Prior Evidence and Unresolved Issues

Rather than commit the financial or political resources necessary to create an effective police force, MVD authorities pressured their units to improve official performance indicators, such as the number of arrests and rate of crimes solved (Reference Uildriks and Van ReenenUildriks & Van Reenen 2003; Reference Robertson, Caparini and MareninRobertson 2004). Recent attempts to change these criteria for assessing police performance have proven superficial (Moscow-Helsinki Group 2005). A survey of cadets and recent graduates of a Russian police academy identified “pressure from above to achieve good clear-up rates” as the second most important motive (following “low pay”) for police to use their position for their own ends (Reference Beck and LeeBeck & Lee 2002). But official performance targets also greatly increase the incentives for police to use beatings and torture to compel detainees to “confess” to crimes. A report by Human Rights Watch (1999) cites this pressure from above as an important factor behind the many instances of violent abuses it documents and also provides evidence of gratuitous beatings of indigents and drunks held in “tanks” by the police (see also Moscow-Helsinki Group 2005).

Russia's human rights ombudsman, Vladimir Lukin, describes specific cases where suspects were beaten or tortured in order to extract confessions, practices he describes as common (RIA Novosti 2004). A news article reports that 25 percent of the respondents in a 2004 poll conducted in 12 large Russian cities claimed they had been beaten or tortured by the police (“Poll: 25% Victimized by Police,”The Moscow Times, 21 May 2004, p. 3). A particularly vicious series of police operations took place in the city of Blagoveshchensk in Bashkortostan (a Russian province in the Volga region with a large Muslim population) in December 2004. Local police, accompanied by members of the special police forces (OMON), rounded up hundreds of young men in cafes, restaurants, and other public places, beat them severely, and held them illegally for several days (Reference RabinovichRabinovich 2005). Although the Russian press (Reference BelashevaBelasheva 2005) covered the incident, the ensuing investigation has yet to produce significant punishment for the police officers or officials involved (Amnesty International 2006). As recently as March and April 2007, police forces brutally attacked crowds of peaceful marchers and passersby at small protest demonstrations in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Nizhnyi Novgorod (see Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2007).

In addition to police violence, police corruption has also apparently become common since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In its most common forms, police demand bribes for minor infractions or shake down citizens for cash (Human Rights Watch 1999; Reference FeiferFeifer 2003). High-level MVD officials have been implicated in investigations of organized crime activities, and there are numerous reports of police involvement in protection and extortion rackets (Center for Strategic and International Studies 1997). Beck and Lee report that “large numbers of respondents” in their survey of police cadets and new officers said many specific corrupt behaviors by police are “morally acceptable” (2002:360–1). Gavrilova et al. cite data from an unpublished study (Reference KolennikovaKolennikova et al. 2002) based on 2,209 interviews with police officers that 50 percent “make extra money by engaging in up to fifty activities unrelated to their duties, many of which are illegal … bribe-taking, registering stolen cars, drug and arms dealing, selling fake passports, and kidnapping” (2003:142). Reference SalagaevSalagaev's (2004) investigative study identifies a range of connections between police and organized crime groups in the Russian province of Tartarstan.

According to Ivkovic, 9.9 percent of the Russian respondents to the 1996/1997 International Crime Victim Survey (ICVS), a survey of urban samples in 41 countries, said they were asked to bribe a policeman during the past year (2003:614; see also Reference ZvekicZvekic 1998). Among the 18 transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe included in the study, only Bulgaria had a higher rate (at 10.5 percent). Yugoslavia and Croatia were somewhat close (about 7.0 percent), Lithuania and Slovakia more distant (at about 4.5 percent), and the remaining countries all quite far behind at 3.3 percent (Ukraine) or lower. Only three of 13 developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America had higher rates than Russia (Indonesia, Argentina, and Bolivia). The rates were below 1.0 percent in all eight Western European countries and Canada, and below 1.5 percent in the United States. Based on this comparative benchmark, police corruption appears to be especially widespread in Russia. However, the Russian ICVS was conducted only in Moscow, so these results, while useful for comparative purposes, may not reflect the situation in the rest of Russia.

The MVD itself has acknowledged the severity of the police corruption problem, spearheading anticorruption campaigns such as “Operation Clean Hands” in 1996 (Reference Waller, Sachs and PistorWaller 1997) and the “Werewolves in Uniform” campaign in 2003 (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2003). The MVD censured 21,000 officers for various offenses in 2002, and fired 17,000 (Reference FeiferFeifer 2003). But these measures have evidently met with skepticism on the part of the public. Russian President Reference PutinVladimir Putin complained in his 2005 state of the union address: “[w]e need the type of law-enforcement agencies in whose work the upstanding citizen can take pride, instead of crossing to the other side of the street when he sees a man in uniform. Those, whose main goal is personal gain, rather than upholding the law, have no place in the law-enforcement system” (2005: n.p.).

Unresolved Questions

Interviews with victims, journalistic reports, insider informants, studies of the police, official pronouncements or statistics, and surveys of geographically limited areas all suggest that police violence and corruption are very serious problems in contemporary Russia, perhaps sufficiently widespread to qualify Russia as a case of predatory policing (see also Reference GlikinGlikin 1998; Reference GilinskiiGilinskii et al. 2002). But these data sources are not suitable for quantifying more precisely their prevalence and consequences, or for examining whether particular socioeconomic or ethnic groups are singled out for victimization. In addition, prior research has not examined subjective dimensions of police abuse such as the links between experiences of misconduct and views toward the police and possible tolerance of violent police practices. Most important for our purposes, the available research gives us no basis for determining whether policing in Russia is better described as predatory or as a case of divided society policing. We turn now to our survey and focus group data, which allow us to answer this question and address the other limitations in prior research on police misconduct in Russia.

Data Sources

Surveys

The bulk of our data come from six surveys conducted in Russia from spring 2002 through summer 2004 by a Moscow-based survey research firm that has set the industry standard in Russia since 1990 (see Table 1). The organization was known as the All Russian Center for Public Opinion Research (VTsIOM) until fall 2003. At that time central government authorities took over VTsIOM (under the guise of privatization) and dismissed its founding director, Yuri Levada. Virtually all of VTsIOM's erstwhile staff left the organization and joined Levada in forming the Levada Analytic Center, which conducted our 2004 surveys.Footnote 4

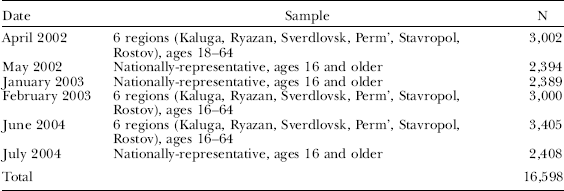

Table 1. Survey Data

Three of the surveys, conducted in May 2002, January 2003, and July 2004, were part of a series of bimonthly “monitoring” surveys of the Russian population applied to nationally representative probability samples, drawn according to standard multistage procedures.Footnote 5 To the core set of questions, we added pretested questions on experiences of police abuse, confidence in a variety of political and social institutions, and other topics related to human rights and democracy. We included a specially designed module examining attitudes toward the police, the courts, and various police interrogation techniques in the July 2004 national survey.

The other three surveys were “regional” surveys implemented by the same organization in six Russian provinces: Kaluga and Ryazan (both near Moscow), Perm and Sverdlovsk (in the Urals region), and Rostov and Stavropol (in the Northern Caucasus). The regional surveys were part of another project that called for moderate age restrictions of the samples (see Table 1). These regions may not be representative of Russian regions more generally. Accordingly, for analyses where we combined the regional and national data sets, we applied data weights calculated to limit the statistical power of the data from those six regions so that it roughly equaled the statistical power of the data from equivalent provinces sampled in the national surveys. We also applied data weights to individual survey respondents to ensure that sample distributions across gender, age, locality type, and education categories reflected known population distributions.Footnote 6 Our combined data file includes 16,598 observations.

Measures

Our surveys asked respondents to indicate whether they or their family members have “experienced during the last two or three years any instances of violence (beating, torture, other forms of physical assault) on the part of the police [militsia].” Based on responses to this question, we assess the prevalence and sources of variation in exposure to police violence. We also asked whether respondents or family members “experienced during the last two or three years any illegal actions on the part of the police that did not involve violence, such as the demanding of bribes, refusal of residential registration, illegal investigation, threats, and so on.”Footnote 7 We interpret affirmative answers as encounters with police corruption and accordingly use this measure to assess its prevalence and correlates.

While they both directly tap into personal experiences of police misconduct, these measures are far from perfect. In particular, our measure of encounters with corruption does not perfectly correspond to our definition of corruption (the use of position to extract rents): while demanding a bribe clearly constitutes corruption, the other examples may or may not. However, our reading of the literature on Russian police abuse cited above leads us to believe that the vast majority of affirmative answers to the second question reflect demands for bribes. In addition, the other actions mentioned probably related to corruption. While in some cases police may have denied respondents registration, investigated them illegally, or threatened them for purely political or ideological reasons, it is highly likely that most such actions were intended to extort money, goods, or favors from the respondents.

Generally, the extent of police misconduct is hard to measure (see Reference IvkovicIvkovic 2003). Respondents may be reluctant to discuss what must have been painful and, possibly, humiliating experiences. Thus our estimates of prevalence may be downward biased. Respondents may have also idiosyncratically interpreted the notions of violence and nonviolent mistreatment, perhaps overstating their incidence. Flawed though they may be, our survey questions offered a more systematic and replicable measure of how many Russians experience different forms of police abuse than can be gleaned from government statistics, interview-based studies, and public assertions by activists or officials. Moreover, survey research is the only methodology that permits us to systematically examine the correlates (both predictors and consequences) of citizen experiences of police misconduct. This is why survey questions similar to ours have been used in many studies of the correlates of police misconduct in the United States and Canada (Reference Smith and HawkinsSmith & Hawkins 1973; Reference KoenigKoenig 1980; Reference Scaglion and CondonScaglion & Condon 1980; Reference TylerTyler 1990; Reference WortleyWortley et al. 1997; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2002; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 2004). In any case, our focus groups let us examine some of our questions of interest using an alternative method.

Focus Groups

To obtain more information on how Russians think about the institutions and issues covered in our surveys, we conducted nine focus groups of 9–12 participants each in the provincial capitals of Ryazan, Perm, and Rostov regions in July 2002. Staff from the Center for Independent Social Research of St. Petersburg helped us develop a question guide, recruited participants in the groups, and moderated the discussions, which we observed. We have extensive notes on all groups and transcripts from all but one (where recording equipment failed). In each city we ran one group consisting of young adults (under age 30) and two with mixed ages. The greater depth and richer details the focus groups offer regarding the consequences of and attitudes toward police misconduct make them a valuable supplement to our quantitative data.

Quantitative Results

How Widespread Are Public Encounters With Police Violence and Police Corruption in Russia?

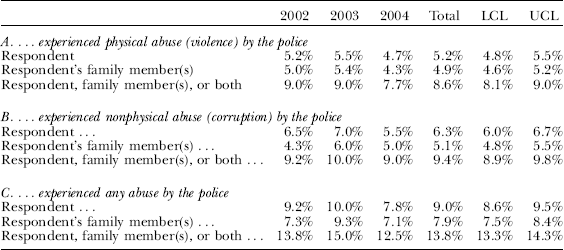

The distributions of responses to our questions about experiences with police violence and corruption remained fairly stable across the three waves of surveys we conducted, suggesting no discernible trend in the prevalence of abuse (see Table 2). Overall, 5.2 percent of our respondents say they experienced physical abuse by the police during the last two to three years, 4.9 percent say family members did, and 8.6 percent say either they or their family (or both) did.Footnote 8 The corresponding figures for experiences of corruption are similar: 6.4, 5.1, and 9.4 percent. Combining acts of violence and corruption, our data suggest that 9.0 percent encountered some kind of police misconduct directly in the last two to three years, 7.9 percent have family members who experienced it, and 13.8 percent did so either directly or through family members.

Table 2. Reported Experiences of Violence and Corruption by the Police During the Last 2–3 Years

Note: LCL and UCL denote, respectively, upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Weighted National and Regional Surveys from 2002–2004.

These numbers are smaller than some reported by the media and human rights organizations (Human Rights Watch 1999). However, a survey that reported 25 percent of respondents had experienced violence by the police was conducted only in Russia's 12 largest cities: sample size and possible restrictions were not mentioned (“Poll: 25% Victimized by Police,”The Moscow Times, 21 May 2004, p. 3). Police violence is more prevalent in big cities than elsewhere (see below), so this figure cannot be generalized to the broader Russian population. That study appears to have asked about encounters ever experienced with the police, not just encounters during the last two to three years. Moreover, our figures are replicated across three waves of surveys.

In any event, our results indicate that police misconduct is indeed prevalent. Official figures put the number of Russians ages 16 and older on January 1, 2004, at 119,154,119 (Goskomstat 2004). Our point estimates of 5.2 percent of Russian adults victimized by police violence in any two- to three-year period, 6.3 percent by corruption, and 13.8 percent by some form of misconduct directly or via family translate into roughly 6.2, 7.6, and 16.4 million acts of police misconduct. These numbers are staggering: police misconduct is widespread, even commonplace, in Russia today.Footnote 9

How do our estimates from Russia compare with estimates of the prevalence of police misconduct in the United States? Weitzer and Tuch report that in a sample of 1,792 Americans, roughly 3 percent of whites and 9 percent of blacks and Hispanics say that the police have at some point used “excessive force” against them; 3 percent of whites, 8 percent of Hispanics, and 10 percent of blacks say they have “seen a police officer engage in corrupt activities” (2004:315). These numbers imply that police violence and corruption are considerably less frequent in the United States than in Russia, at least for whites, and possibly also for Hispanics and blacks. However, “excessive force” does not necessarily entail violence, and the question in the American survey asks about “seeing” police corruption, not about being a victim of police corruption. Thus the numbers reported by Weitzer and Tuch probably overstate the prevalence of police violence and corruption relative to our estimates from Russia. Moreover, their questions pertain to any experiences in the course of one's entire life, while our Russian survey questions are limited to experiences in the last two to three years. A crude comparison therefore suggests that Russians experience about twice as much police violence and corruption in the course of two to three years than Americans experience in the course of their lifetimes. Third, their sample is drawn from cities with at least 100,000 inhabitants, where, according to the authors, police misconduct is particularly salient (Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 2004:310). Finally, studies by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics report much lower rates of the use of force by the police in the United States: a nationally representative 1996 survey of 6,241 respondents age 12 or older found that only 0.2 percent (1 in 500) were “hit, held, pushed, choked, threatened with a flashlight, restrained by a police dog, threatened or actually sprayed with chemical or pepper spray, threatened with a gun, or experienced some other form of force” in the last year (Reference GreenfieldGreenfield et al. 1997:12).

In answer to the first question, which distinguishes predatory from divided society policing, our results show that police corruption is slightly more widespread than police violence: 9.4 percent report experiencing corruption themselves, via their family members, or both, while the corresponding number for police violence is 8.6 percent. Each point estimate is outside the confidence interval around the other. Although there is a very small overlap in the intervals themselves, the most reasonable interpretation of the data is that they indicate that corruption is at least as common as violence, and in fact probably somewhat more common. This is our first indication that the predatory policing model better characterizes Russia than the divided society model.

Does Exposure to Police Misconduct Vary by Social and Economic Characteristics?

Our surveys confirm findings from interview-based reports that younger males experience the most police violence (Human Rights Watch 1999): 11.2 percent of males under 40 in our sample report recent experiences of police violence, compared to 9.0 percent of males in their forties and substantially lower percentages of older males and females of all ages. A similar pattern holds for police corruption, reported by 13.3 percent of males under 40 and 9.6 percent of males in their forties. Combining the two forms, our data indicate that 18.7 percent of Russian males under 40 personally experience police misconduct in any two- to three-year period. The figure is somewhat lower (9.3 percent) for males in their forties and does not exceed 6.0 percent for females of any cohort. Clearly, the police are most likely to target men under 40. Even if young males are more likely to commit crimes and thus come into contact with the police as criminal suspects, that hardly excuses or explains their disproportionate exposure to illegal police abuse.

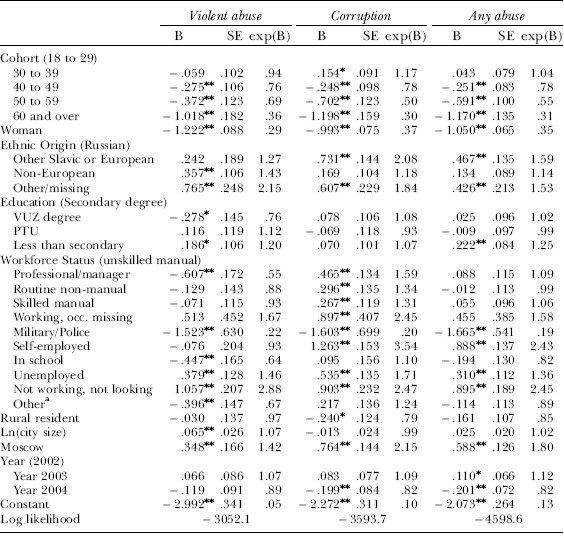

The divided society model of policing suggests that ethnic minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status are disproportionately victimized by police misconduct. Even in the United States, where the divided society model seems to be inappropriate as a characterization of the main tendency of policing (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 1995), race/ethnicity, social status, and urban residence affect exposure to police abuse (Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 2004). To determine how these factors relate to exposure to police misconduct in Russia, we estimate logistic regression models for each form of abuse separately and for the two combined (see Table 3). The multivariate models confirm the descriptive findings regarding the effects of age and gender.

Table 3. Logistic Regressions: Who Experienced Police Misconduct in the Last 2–3 Years?

Note: Dummy variables for residence in each of the six provinces in our regional surveys are included in all models, but not shown.

Source: Pooled 2002–2004 data, weighted. N=16598.

** Statistically significant at p<.05, two-tailed.

* Statistically significant at p<.05, one-tailed.

a “Other” category includes retired, disabled, maternity leave, homemakers, other nonspecified, and missing activity.

Citizens of Russia who are of non-European ethnic origin are more likely than ethnic Russians to encounter police violence, controlling for the other variables: the metric coefficient of 0.357 implies that their odds of victimization are 43 percent (e0.357=1.43) higher.Footnote 10 The difference between ethnic Russians and other Slavic or European ethnicities is not significant, suggesting that racism on the part of police officers may be behind the disproportionate exposure of non-Europeans.

What is most surprising about the effect of ethnicity is that it is so small. The odds ratio of 1.43 implies, for example, that if an ethnic Russian with particular characteristics has a 0.053 predicted probability of experiencing police violence in the last three years (the national average for all adults), then a non-European-origin Russian citizen with the same characteristics has a 0.073 predicted probability.Footnote 11 Compared to ethnic Russians whose characteristics give them a 0.030 predicted probability of experiencing police violence, non-Europeans in Russia have a 0.042 predicted probability. These differences, while statistically significant, pale in magnitude to the 9 versus 3 percent black/white difference in exposure to “excessive force” in the United States reported by Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer and Tuch (2004). In their study arguing that disproportionate police violence against blacks in Brazil undermines that country's status as a democracy—which is consistent with divided society policing—Mitchell and Wood report a black/white ratio of the odds of exposure to police assault among young men of 2.40, corresponding to a 0.069 predicted probability for blacks who have the same characteristics as whites with a 0.030 probability (1999:1014). Thus although police violence disproportionately targets non-European ethnic minorities in Russia, the magnitude of the ethnic differences is much smaller than in other countries.

Non-Europeans are no more likely to experience police corruption than are ethnic Russians, controlling for other variables. Yet those of other Slavic or European ancestry are more likely than ethnic Russians to be victimized in this way (their odds are about twice as high). In terms of exposure to any form of abuse, the latter effect clearly prevails, as the effect of non-European ethnic origin is again nonsignificant. Altogether, the ethnic differences in exposure to police misconduct in Russia are too inconsistent and small in magnitude to conform to a divided society model of policing.

The effects of social status, as measured by education, workforce status, and occupation, also vary by type of abuse. University graduates are less likely than high school graduates to experience police violence; high-school dropouts are more likely. Compared to manual workers (the omitted category on workforce status and occupation), professional-managerial workers, students, and police officers/military personnel are less likely to experience police violence. The latter finding suggests that police officers are loath to target other officers or soldiers due to occupational solidarity or fear of reprisal. The unemployed and those who have given up looking for work are more exposed to police violence than are unskilled workers (and, by extension, the other groups of employed workers). These findings all indicate that, to some degree, higher social status helps insulate Russians from police violence. The police may feel they have greater impunity to brutalize lower-status individuals, and higher-status Russians may be more adept at avoiding contact with the police.

The picture is more mixed with respect to the probability of experiencing police corruption. Education has no net effect. Unskilled workers have fewer such experiences than professional-managerial, routine nonmanual, and skilled manual workers. In turn, the self-employed are significantly more likely to report corruption than all three of these categories of hired employees.Footnote 12 The self-employed (and, to a lesser extent, professionals and managers) make good targets for bribes because they are likely to have cash to pay, and the vast number of regulations and taxes that apply to them encourage “violations” that can be forgiven with a bribe. Unemployed and discouraged workers also experience more police corruption than unskilled workers.

To gain a more intuitive sense of the magnitude and pattern of effects of ethnicity and social status on exposure to police violence and abuse in Russia, consider the predicted probabilities implied by our models for different combinations of education, workforce status, and ethnicity, estimated for males under 30 living in cities other than Moscow with more than 1 million residents (see Figure 1). The first pair of columns pertains to those with the lowest social status (unemployed high school dropouts), the second and third pair to working and middle-class status (unskilled workers and self-employed workers with secondary degrees), and the fourth pair to higher status (university educated professionals). For each of these combinations, predicted probabilities for ethnic Russians and non-Europeans are shown.

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities of Experiencing Police Violence and Corruption, Russian Males Under 30 in Large Cities With Various Ethnic and Socioeconomic Traits.

The predicted probabilities answer the second question that distinguishes predatory policing from divided society policing: Do all groups experience significant levels of police misconduct, even if some groups are disproportionately exposed? Although higher-status groups and ethnic Russians are somewhat less exposed to police violence than lower-status groups and non-Europeans, the differences are relatively small in magnitude. Most important, no group of young men is immune. Even among ethnic Russian university-educated professionals, the predicted probability is 0.048. At the other extreme, the predicted probability for non-European unemployed high school dropouts is 0.110. Thus while elites are less than half as likely to experience police violence as the most subordinate of groups are elites do nonetheless experience a substantial rate of police violence. As for corruption, the differences by ethnicity are negligible and nonsignificant; the differences by status are small and do not correspond to a hierarchical status gradient. Our data again indicate that predatory policing is the best model to describe Russia.

Before turning to the next set of analyses, we note that in Russia, as elsewhere, city size has positive effects on both violent and nonviolent abuse: the larger the size of the locality, the more abusive the police. Presumably, greater concentrations of police mean more contact between them and the public in larger urban areas. Both forms of police abuse are especially rampant in Moscow, even controlling for its distinctively large size. This probably reflects local policies encouraging police intimidation of racial minorities and immigrants and the opportunities for extortion and bribery provided by Moscow's unconstitutional withholding of residency registrations from many newcomers. We also include dummy variables for the six regions we sampled in our three regional surveys, to control for possible regional effects not absorbed by our weights, but we do not show the estimates of these “nuisance” parameters.

How Do Russians Perceive the Police, the Courts, and Violent Police Methods?

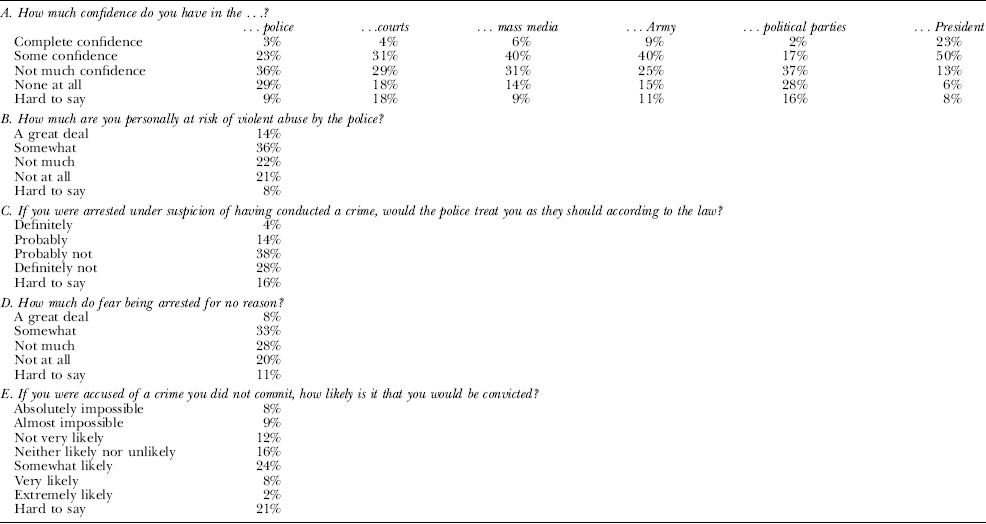

We examine a range of questions pertaining to attitudes toward the police and the courts (see Table 4). Our 2003 and 2004 surveys asked how much “confidence” or “trust” (the Russian word, doveriia, can mean either) the respondent has in six institutions: the police, the courts, the army, the mass media, political parties, and the President of Russia. Combining the surveys (which exhibit trivial change over time), only 3 percent of respondents say the police “fully” deserve trust, 23 percent say they “probably” deserve it, 36 percent say “probably not,” and 29 percent say “not at all.” The remaining 9 percent find it hard to say. Our data indicate that barely one-quarter of the adult population has confidence in the police, and most of these have only partial confidence. About two-thirds do not trust the police. Trust in the courts is only slightly higher: 35 percent trust them to some degree, while 47 percent do not trust them. Russians have little confidence in their law enforcement and legal institutions.Footnote 13

Table 4. Attitudes Toward the Police, Courts, and Other Institutions

Note: Source for panel A is weighted national and regional surveys from 2003 and 2004 (N=11,202). Source for panels B through E is the weighted July 2004 national survey (N=2,408).

Russians' levels of distrust of legal institutions are high by international standards. According to the World Values Survey, on average 80 percent of the populations of Western European countries trust the police, and 66 percent trust the courts (Reference Mishler and RoseMishler & Rose 1997:429). Even in post-Soviet Ukraine, which shares many similarities with Russia, 43 percent of respondents in a 2000 survey conducted in a large city (Kharkiv) said they trust the police, and 31 percent said they do not (Reference Beck and ChistyakovaBeck & Chistyakova 2002:127). Only 10.2 percent of the Russian respondents to the 1996 ICVS said that the police “do a good job,” lower than in any of the other transition countries surveyed (Reference ZvekicZvekic 1998:78)

Perhaps Russians distrust all institutions and see the police or courts as no worse than others. In fact, the distribution of responses for the other four institutions we asked about show that levels of trust vary substantially by institution, and political parties are the only institution Russians trust less than they trust the police. Russians tend to trust the mass media, the army, and the President, but not political parties, the police, or courts. While Russians may view many institutions with skepticism, they have especially negative views toward the legal institutions and political parties. This contrasts sharply with the situation in the United States and Europe, where the public holds the local police in higher regard than most other governmental and civil society organizations, including the media, the U.S. Supreme Court, and a range of NGOs (Reference PeekPeek et al. 1978; Reference Mishler and RoseMishler & Rose 1997; Reference Newton, Norris, Pharr and PutnamNewton & Norris 2000). In sum, our data indicate that the Russian public is unusually suspicious of the police and courts, both relative to other countries (including other transition countries) and relative to other public institutions in Russia.

More detailed questions on our 2004 national survey reveal additional evidence of widespread mistrust and fear (Table 4, panels B–E). Asked how much they personally fear being physically abused by the police, half the respondents answered “at least somewhat.” Only 4 percent are certain they would be treated according to the law if they were arrested, while two-thirds say probably not (38 percent) or definitely (28 percent) not. We find that 41 percent fear “somewhat” or “a great deal” being arrested for no reason; only 20 percent are completely free from this worry. Finally, only 29 percent find it unlikely that they would be convicted if charged with a crime they had not committed, and 34 percent find it at least somewhat likely. Russians are clearly uneasy over the police and courts. They fear arbitrary arrest, violence, and illegal treatment by the police. They doubt the courts would acquit them of a crime they did not commit.

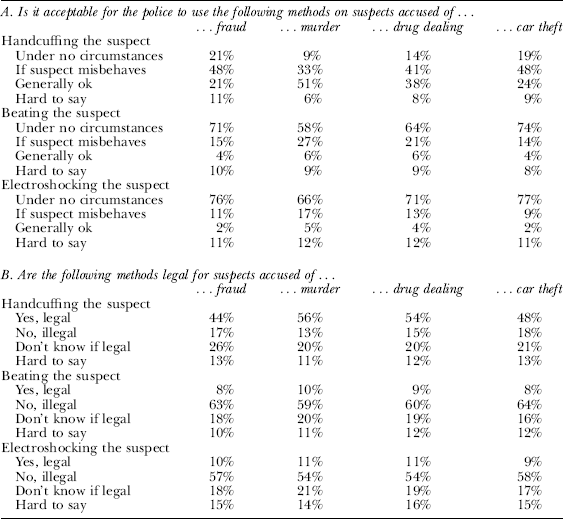

An additional set of questions on the July 2004 national survey ascertains whether Russians see some forms of police violence as acceptable, which they might due to an authoritarian political culture or concerns about rising crime. To see if views on police practices vary depending on the type of offense, we asked respondents to imagine scenarios where the police arrested suspects for defrauding a business partner (white-collar crime), stealing a car (petty property crime), selling heroin to a neighbor (serious, but not a capital offense), and murder (capital offense). For each scenario, we inquired whether three different actions of the police are acceptable, are legal, and should be legal: handcuffing the suspect during arrest and transport to the police station, beating and/or kicking the suspect, and electrically shocking the suspect (see Table 5).

Table 5. Attitudes toward specific police practices

Source: Weighted July 2004 national survey, N=2,408.

Not many Russians (9–21 percent) categorically reject the use of handcuffs at the time of arrest, a standard police procedure in many countries. Substantial majorities say that beating and electroshocking are not acceptable, with some variation by type of offense: 71–76 percent categorically reject beatings or electroshocks for fraud and car theft suspects, but the numbers drop to 58 and 68 percent for murder suspects. Still, most reject these violent methods even for murder suspects. Moreover, most who accept them do so only when the suspect misbehaves or tries to escape. Very few (2–6 percent, depending on the nature of the offense) say it is generally OK for the police to beat or shock suspects.

Most Russians also know that Russian law prohibits beating or electrically shocking suspects regardless of the offense. Only small minorities (8–10 percent) believe these practices are legal; most understand that they are not (54–64 percent). However, fairly large numbers are uncertain about their legality or decline to answer the question. Views of legality do not vary much by type of offense: most respondents correctly assume that the type of offense has no bearing on the legality of particular police practices. Responses regarding whether these practices should be legal for suspects of different crimes broadly follow the pattern regarding whether they are acceptable (results available upon request).

Most Russians oppose the use of violence and torture by the police: they do not think these practices are acceptable or should be legal even if the suspect misbehaves or tries to escape. Public concern about the rise of crime and drug addiction has not translated into broad public support for brutal police interrogation methods. Furthermore, most Russians understand that these methods are illegal, regardless of what crime a suspect has allegedly committed. The prevalence of these methods cannot be attributed to their normative acceptance by the public or to a widespread misconception that they are legal. Of course, neither the rejection of brutal techniques nor the knowledge of their illegality is universal. But public attitudes are hardly tolerant of police violence and torture: if anything, they constrain rather than enable abuse.

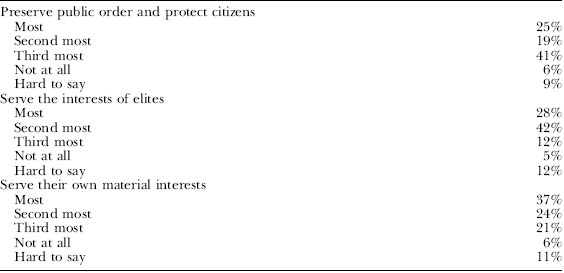

Finally, we have data that directly bear on the third question that distinguishes predatory from divided society policing: is the main motive for police misconduct to advance the material or corporate interests of the police rather than to suppress subordinate groups? It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to definitively measure the main or predominant motive that drives police misconduct. Our approach is to ask what the public perceives to be the main role of the police in Russia. If the public perceives the police as operating mainly to advance their own material interests, it provides some indication that their violent and corrupt practices are predatory rather than politically motivated. If, on the other hand, the public tends to perceive their main role as advancing the interests of elites or preserving public order, then the divided society or functionalist models would appear to be more valid. Of course, we recognize that public perceptions of police motives can be mistaken or misleading, but nonetheless we would maintain that they offer some insight into actual police motives: after all, these are the opinions of people who come into regular contact with police officers—directly or through their family, friends, and acquaintances—and thus their views are grounded in experience.

Accordingly, we asked respondents which of three activities the police do most of all, second most, and third most: safeguard public order and protect citizens, serve the political and economic interests of those in power, or pursue their own material interests.Footnote 14 For each activity, we also provided the option that “the police do not do it at all.” Only one-quarter of our sample believe that the police protect the public first and foremost (see Table 6). Nearly half (47 percent) say this is only the third priority of the police, or that they do not do this at all. Twenty-eight percent cite protecting elite interests, and 37 percent cite pursuing their own material interests as the top priorities of the police. Thus a plurality of Russians see the police as predatory—serving their own material interests—above all. In the view of the public, self-interest rather than elite interest is the driving factor behind police misconduct, yet another finding that points at predatory policing as the most appropriate model.

Table 6. What do the police do most of all, second most, third most?

Source: Weighted July 2004 national survey, N=2,408.

How, If at All, Do Experiences of Police Misconduct Affect Perceptions of the Police and Courts?

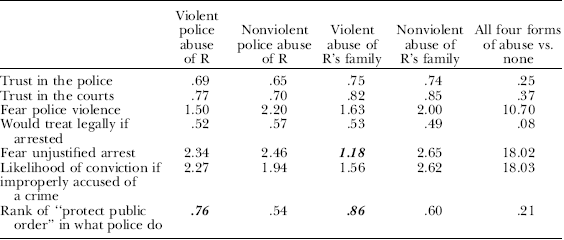

To assess whether personal experiences of police misconduct affect attitudes toward the police and the courts, we estimated seven multivariate ordinal logit models, where the dependent variables are the ordinal measures of perceptions of the police and the courts presented in Tables 4 and 6. Each model includes four dummy variables indicating, respectively, that the respondent and the respondent's family experienced police violence and corruption during the past two to three years, plus all the variables in our models for experiences of police misconduct (see Table 3) as controls. Here we report only the effects of experiences of misconduct, net of age, sex, ethnicity, education, social status, and place of residence. We present the exponentiated coefficients, because their magnitudes can be interpreted intuitively as “multiplier” effects: values above one imply that the cumulative odds of having a value at least as high as a particular value rather than a lower value are increased by experiencing abuse in a particular form by that factor; values less than one imply that the odds of the outcome are decreased by that factor (see Table 7). The final column presents the aggregated effects of experiencing all four forms of abuse (as roughly 1 percent of our respondents report) versus experiencing none of them.

Table 7. Effects of Experiences of Police Misconduct on Views Regarding the Police

Note: These are exponentiated coefficients from multivariate ordinal logit models described in the text. All models contain controls for age, sex, ethnicity, education, workforce status, and place of residence. All reported coefficients are statistically significant at p<.05 except for those in bold italics.

Experiences of police of misconduct significantly shape perceptions of the police and the courts, controlling for other variables. For a number of attitudes, all four variables measuring (different) exposure to abuse have significant, predictable effects. For example, respondents who themselves experienced police misconduct have lower odds than those who did not (by a factor of 0.69) of falling in higher rather than lower categories of trust in the police.Footnote 15 A direct encounter with police corruption similarly reduces trust in the police, as do family members' exposure to police violence and corruption. Those who experience misconduct in all four ways have only one-quarter the odds of falling in higher categories of trust.

Each type of encounter with police misconduct also generates skepticism about the courts, whether we use our trust measure or our question about the likelihood of being falsely convicted. Police abuse not only diminishes public confidence in the police, but it also leads the public to view the entire legal system in a more negative light. This is a striking finding, because it suggests that negative experiences with one law enforcement institution reflect badly on other law enforcement institutions. We have not seen any study apart from Reference TylerTyler (1990) test for such a generalized effect of negative encounters with police. However, we find that experiences of police abuse do not affect trust in other, non-law enforcement institutions (results not shown). Thus the effects are specific to the relevant institutions. All types of encounters with police abuse increase fear of police violence and decrease the expectation of fair treatment if arrested. All except family members' experiences of violence increase the fear of being unjustifiably arrested. Police corruption victimizing oneself or one's family decreases one's ranking of protecting public safety as a police activity.

In Russia experiences of police misconduct—of self or family, violent or nonviolent—increase mistrust and fear of the police specifically and the legal system in general. Thus rampant police abuse in contemporary Russia undermines public trust in the legal system. While cultural dispositions and the memory of Soviet-era experiences may also play a role in making Russians skeptical of their legal institutions, the current dysfunctional performance of the police contributes independently to that skepticism. This conclusion implies that if the police change their predatory behavior, public confidence might be restored. We find further evidence for this claim in our focus groups.

Focus Group Themes

The moderator asked participants in our focus groups whether they have confidence in the police (militsia), as well as the other institutions covered in our surveys. This was our only question about the police, but apart from the army and the war in Chechnya, no other topic provoked as much emotion. The heated response shows that police misconduct is not an abstract societal problem, but an immediate and upsetting part of day-to-day reality for many Russians, one upon which they reflect and offer theories to explain. The words of these anonymous Russian citizens bring to life the concerns and experiences covered by the survey.

When the moderator raised the topic of the police, one participant commented: “I think that no other branch has violated as many persons' human rights as the militsia” (R2).Footnote 16 Others spontaneously recounted specific episodes of unprovoked police violence they experienced, heard about, or witnessed. One was detained and roughed up for no reason in front of an “Alfavit” store (R1). Another's acquaintance was beaten so badly that he suffered permanent brain damage (O3). Another's daughter said the police helped local toughs beat participants in a peaceful political demonstration (R2). Another saw police handcuff a homeless man to a pole, then hit him in the kidneys with batons; on a different occasion, he saw police chase a man for “150 meters” before beating him until there was a “puddle of blood” (R3). Another reported physical attacks on different family members (P3). One participant, a doctor at a local hospital, countered another who spoke positively of the police:

[Y]ou don't work in a hospital and you've never seen how many beaten people [the police] bring in. It is appalling, simply appalling. They just haul them in, dump them off, and leave, as if they just cleaned them off the streets. So many. Literally one every day. One a day (O2).

While this doctor finds the level of police abuse witnessed with her own eyes appalling, in general the examples of arbitrary police violence provoke no surprise or outrage. The absence of such sentiments implies that most participants in the groups view police abuse as a fairly quotidian phenomenon in contemporary Russian society, a problem provoking intense discussion and strong feelings, but not shock.

Participants also decried police corruption and described incidents of bribery. Several described being shaken down by police officers (P1, O3). One woman said the police refused to protect her family from harassment because the suspect had paid a bribe (R2). Others equated police with muggers:

[T]here are some good men in the police who are professionals, who honestly struggle to do something despite their low pay. And there are also an enormous number of low-lifes [bydla] who, well, just beat and kick you in the entryway. That is, a typical mugging. And they take whatever they can. Because they want to get drunk and they are messed up in the head.

–Well, sometimes they first ask you for money [before beating you up].

–Not necessarily (R3).

Participants also complained about the incompetence of the police (R1, R2), their inability to solve serious crimes such as robbery or murder (R2, P3), their unfairness (P2), indifference (O1, O3), “rudeness and cruelty” (P2), and accusatory or lewd reactions to complaints (O3, P3). A prevailing sentiment in the groups was one of despair that the police are not up to the task of preserving public safety: “Since the police won't protect you, then whom can you turn to?” (O1). Typical comments portrayed the police as more interested in lining their pockets than in investigating crimes or preserving public order:

The militsia don't haul away the drunken bums. For the most part they arrest people who are still on their feet and walking in an orderly manner, because they can take something from them. They don't respond to calls (R2).

Such experiences produce antipathy toward the police:

And when they stop us for absolutely no reason and try to take us to their building to try to get money out of us for their own financial purposes—that, of course, creates negative reactions. The same goes for the highway police [GIBDD]. Therefore, I think that increasing their salaries will not be enough. The real problem is that most who join the organs of the militsia are unworthy people, many even have a criminal record (R1).

This last comment points to a typical explanation offered for rampant police abuse and corruption: the low quality of recruits. As others put it:

[T]he least educated, uncultured guys join the militsia, then they try to assert themselves once they have the power. That's where the rudeness, the stupidity, and the numerous violations of the law come from (R2).

I'm not saying we don't need the militsia. But we need people with balanced psyches there. The problem is simply that people with unbalanced psychology, with hunger for power, join the police. It is an awful state of affairs when a man with a mass of complexes obtains some kind of power in his hands in order to then work out [his psychological problems]. I don't know—probably the majority of the militsia are like that. Maybe some of them aren't so bad (O2).

Several different participants suggested that many policemen are demobilized soldiers who lacked any alternative career possibilities, with predictable consequences:

And after the army the only thing they know how to do is to hold a gun and wear a uniform. It is their only skill. The militsia gives them the opportunity to somehow get established in life, because they cannot make it in any factory or commercial structure—they don't have the necessary knowledge. It turns out that the army does not give them the means to realize their potential. Not everyone can find a way to get involved in something before age 18 that would protect them from being taken into the army. The army gives them no possibility to realize their abilities in education, and then they become unwanted. It seems to me that they grow weaker psychologically—they leave the army at 21 with nothing. Those who did not join the army have already gotten set up in life—they finished their education, the most ambitious set up their own enterprises. So, this plays a significant role in producing the kind of militsia that we have (R1).

The militsia are formed by the street. They are young men, 20 to 22 years old, who served in the army. That is, they have had experiments performed on them. You know, in the army the “grandfathers” [experiment] on the young ones.Footnote 17 All kinds of things happen there, the most interesting experiments as to what the human organism can endure. And so what do you expect of these young men—of whom I would guess about 50 percent are damaged, are semi-morons, and so forth? Correspondingly, I have only 1 percent confidence in the militsia. They don't do anything and don't want to do anything (R3).

Other explanations for the poor performance of the police were mentioned only once: bad laws regulating police behavior (R2), failure of citizens to know and stick up for their rights (O2), and the failure to reform the police system after the collapse of the Soviet Union (P2).

Although suspicion and hostility toward the police predominate, there are noteworthy undercurrents of sympathy and support. Several participants said they “want to trust” the police, mainly because they recognize that the police could play a vital role in protecting public safety:

I want to trust the militsia because our security directly depends on them. Therefore, when there have been times in my life when I've had to call the militsia and they at least showed up on time and at least helped me do something, my trust increased. I want it to grow still more (R3).

This comment provoked enough derisive laughter to prompt the moderator to admonish the group members to respect one another. But others also expressed an underlying disposition to trust the police, and the comment suggests that positive experiences with the police can improve citizens' confidence in them. Through more effective performance and reduced misconduct, the police may be able to restore their image, as tarnished as it may be due to their current tendencies. Russian popular culture offers some material for the construction of a positive image of the police:

It's great that they show movies about cops—you know, the famous series [“Cops”] where the police are truly dedicated, willing to risk their lives to do good. But then you see the low-lifes [bydla] in uniform who have weapons, batons, and do whatever they like (R3).

This contrast of television images and reality is not entirely cynical: if the police are often “low-lifes” in Russia today, it is not because they have to be that way.

In fact, several opined that some police officers are honest, dedicated, and capable: “The police are the police. Just like anywhere else there are good ones and bad ones. But overall I trust them” (O2). Some described help offered by the police, even as they recounted incidents when the police had been indifferent, insulting, or abusive. Although no participants expressed unadulterated admiration for the police, several expressed ambivalence:

I would say I have mixed feelings toward the militsia. Yes, on the one hand there are a large number of abuses of their positions, constant rudeness on a daily basis. Naturally, I have a negative opinion from that perspective. But on the other hand, [they] have such a miserly salary, and therefore they get by as best they can—some by abusing power, others by stopping cars on the road, etc. (P2).