Introduction

The trend toward law in industrialized societies and the implications for social life have long fascinated scholars (e.g. Durkheim 1964 [Reference Durkheim1933]; Habermas Reference Habermas and McCarthy1987; Weber 1978 [Reference Weber1920]) and have become only more significant over time. The dramatic expansion of civil law in the twentieth century brought an increasing array of topics within the reach of rationalized state control (Friedman 1994 [Reference Friedman1985]) such that today we live in a “law-thick” world in which civil law routinely encroaches into everyday life (Hadfield Reference Hadfield2010: 133). There is growing recognition that individuals’ ability to navigate an increasingly legalized world influences their capacity for effective self-determination and the vindication of fundamental rights (Pleasence and Balmer Reference Pleasence and Balmer2019a) and contributes to the reproduction of social inequality (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008).

Research on the unequal use of civil law is dominated by work focused on the reactive use of law in response to problems encountered in everyday life (e.g. Berrey et al. Reference Berrey, Nelson and Beth Nielsen2017; Felstiner et al. 1980/Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980/1981; Miller and Sarat 1980/Reference Miller and Sarat1981; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2000; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Steinberg, Mark and Carpenter2022; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2016). This article posits that proactive instrumental legal behavior – which we term legal actuation – is an underappreciated but significant dimension of how unequal access to law serves as a tool of stratification. The term refers to the process of actuating, or putting into motion, the machinery of law to one’s advantage. This behavior is not evenly distributed across the population. At one extreme are individuals who engage in extensive strategic legal behavior that enables them to optimize outcomes under law, often with the benefit of access to legal and other professional expertise. At the other extreme are individuals who are unaware of legal opportunities or unable to take advantage of the potential benefits available to them under the law, resulting in less favorable outcomes.

While this concept draws on scholarship regarding legal consciousness (e.g. Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Young and Billings Reference Young and Billings2020), social capital (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1986), and rights mobilization (e.g. McCann Reference McCann1994; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2011), it draws attention to a recognized (e.g. Hadfield Reference Hadfield2010) but understudied aspect of individuals’ engagement with law in everyday life. In contrast to an emphasis on ex post reactions, it considers ex ante behavior; rather than disputes, it evaluates transactions and other instrumental legal activities; and in lieu of studying group behavior, it focuses squarely on the actions of individuals.

Using estate planning as an empirical case study, this article develops the concept of legal actuation and evaluates its role in generating unequal outcomes under the law. As Friedman (Reference Friedman1966: 340, 352) notes, “One of the chief ways in which the social order carries on over time is through the inheritance and transfer of interests in property…. The very existence of a stable upper class as opposed to a merely wealthy class presupposes the existence of a method of devolution of property at or before death.” The devolution of property at death is effectuated through legal processes that can be controlled through estate planning. Yet, this requires affirmative lifetime action. Thus, the stability of the upper class requires not just the transfer of property at death, but the transfer of legal knowledge and practice that facilitates the legal actuation necessary for such transfers to occur.

This article investigates economic inequalities in legal actuation, emphasizing how legal actuation perpetuates economic advantage. Recognizing that possession of financial assets itself does not generate these results, the article investigates three mechanisms through which economic advantage may operate to structure legal actuation: legal socialization, legal knowledge, and legal capability. The results offer evidence that these mechanisms are indeed economically stratified and are also linked to greater rates of legal actuation. The findings highlight an understudied source of economic advantage with important implications for equal justice and the relationship between law and inequality.

Legal actuation

Defining legal actuation

Situations where people engage with civil law can be distinguished by the nature of the encounter – involving responsive or proactive behavior – and the unit of analysis – individual or group. As Figure 1 illustrates, the combination of these two dimensions generates four types of civil legal behavior. Legal actuation, located in quadrant I, is focused on individuals’ proactive use of law, such as estate planning, which happens before any legal distribution of assets. As in research on legal needs, legal actuation is focused on justiciable events – those “matter[s] experienced by a [person] which raise... legal issues, whether or not [they] are recognized by the [individual] as being ‘legal.’” (Genn Reference Genn1999: 12). However, it differs from the situation described in quadrant II because the justiciable situations involved are not categorized as “problems” to which individuals must respond. Situations in quadrant II involve responses to justiciable problems; in the example provided, an eviction action would prompt any legal response by the tenant. However, as Sandefur (Reference Sandefur, Pleasence, Buck and Balmer2007: 113) has noted, “Not all problems are justiciable, nor are all justiciable events problematic. Marriage, home purchase and starting a new job all have civil legal aspects, but often people do not experience them as problems.” Legal actuation aims to describe those justiciable situations that are excluded from scholarship on individuals’ reactions to “problems” but that may nevertheless result in unequal outcomes under the law owing to variation in individuals’ legal behavior.

Figure 1. Typology of civil legal behavior.

Scholarship on legal consciousness is similarly primarily focused on people’s construction of legality as they respond to justiciable problems (quadrant II). Ewick and Silbey (Reference Ewick and Silbey1998: 57), for example, use emblematic narratives of “disappointments, disagreements, and disputes that characterize daily life” and include “consumer problems, neighborhood parking problems, and health-care billing difficulties” to elucidate the “before the law” orientation to law, in which individuals see law as an impartial and abstract realm that exists apart from the concerns of everyday life. For the “against the law” orientation, they describe individuals’ understanding of law as powerful but unpredictable and inaccessible, which invites people to engage in avoidance or subterfuge to resolve problematic situations.

The “with the law” orientation to legality comes closest to considering the kinds of situations in which legal actuation may occur (quadrant I). In that orientation, people understand legality “as a set of transcendent ordering principles” but they also see law as “an ensemble of legal actors, organizations, rules, and procedures” that can be used, and understand law as an “arena in which actors struggle to achieve a variety of purposes.” (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998: 131). Yet even here, where the motivations and understanding of law are consistent with legal actuation, the behaviors studied are generally responsive. Thus, while research on legal consciousness may help to predict or explain why people engage in different forms of legal behavior, the form of legal behavior that we identify as legal actuation remains largely unexplored within this scholarship.

Similarly, although legal actuation shares a focus on proactive use of law with the social movements described in quadrant IV, it is not centered on understanding the dynamics of groups. Thus, while scholarship on proactive group behavior, such as the literature on social movements and the role of related transactional legal work (e.g. Southworth Reference Southworth1996), offers helpful insights, its focus differs from that captured by the idea of legal actuation. Finally, the situations captured by quadrant III dealing with group responses to justiciable problems (e.g. class action lawsuits), such as in scholarship on group rights mobilization, differ from legal actuation both in terms of the unit of analysis and the nature of the behavior. Unlike in quadrant III, the unit of analysis for legal actuation is not a group but an individual, and their behavior is not in response to wrongdoing or a denial of rights. Thus, despite its kinship with other forms of civil legal behavior, legal actuation represents a distinct socio-legal phenomenon.

Consequences of legal actuation

Although understudied, legal actuation is a phenomenon that is both prevalent and consequential. Given the expansion of civil law into everyday life, individuals are frequently faced with situations where knowledge of the law and a willingness and ability to use such knowledge to act instrumentally present opportunities for enhanced outcomes. For example, individuals regularly file tax returns, enter into service contracts, take out loans, sign rental agreements, and negotiate employment terms. In some situations, individuals are aware of their options and the legal implications of their actions and are empowered to act strategically to attain favorable results. In other cases, however, individuals are less able to optimize their legal behavior. As a result, they may obtain sub-optimal outcomes (e.g. Agarwal et al. Reference Agarwal, Chomsisengphet, Kiefer and Kiefer.2021), forego benefits offered by law because of their inability to navigate the process required to obtain them (Herd and Moynihan Reference Herd and Moynihan2018; Internal Revenue Service 2021; Lanier et al. Reference Lanier, Afonso, Chung, Bryant, Ellis, Coffey, Brown-Graham and Verbiest2022; Revillard Reference Revillard2019), or ultimately face a justiciable problem that results from their inability to successfully address a legal issue ex ante (Hadfield Reference Hadfield2010). Indeed, there appears to be a link between legal actuation and several common types of justiciable problems, including problems with employment, debt, insurance, and government benefits, which can involve issues like “confusion about policies and terms” (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2014: 7).

Predicting legal actuation

A robust and growing literature documents the production and reproduction of economic inequality as a result of variation in the incidence of justiciable problems and individuals’ responses to the problems they experience (e.g. OECD/Open Society Foundations 2019; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2019). There is good reason to expect that opportunities for legal actuation and success in leveraging those opportunities are similarly stratified by economic status. Indeed, given the hidden nature of many opportunities for legal actuation, this variation may be even more pronounced than for other forms of individual civil legal action.

Although justiciable problems are prevalent across all sectors of the population, the incidence of particular types of justiciable problems is socially patterned (e.g. HiiL and IAALS 2021; Legal Services Corporation 2022; Young and Billings Reference Young and Billings2023), as is the likelihood of experiencing clusters of civil legal problems that frequently co-occur (Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Balmer, Buck, O'Grady and Genn2004). This reflects both participation in social and economic life – which increases exposure to circumstances that can give rise to problems – and being unable to avoid or mitigate problems, which increases the likelihood that such exposure ultimately results in justiciable problems (Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Christine, Suzie and HM2014). Although findings are mixed regarding the relationship between income and the overall incidence of justiciable problems (HiiL and IAALS 2021; Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Christine, Suzie and HM2014; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2014), recent national survey data from the United States finds that individuals in lower-income households are more likely to report experiencing more serious justiciable problems (HiiL and IAALS 2021). This finding is consistent with data from other jurisdictions noting the increased vulnerability of those who are poorer to many types of legal problems (Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Christine, Suzie and HM2014). In addition, there is evidence that economic disadvantage can interact with other individual characteristics to increase the likelihood of experiencing civil legal problems (Young and Billings Reference Young and Billings2023).

Opportunities for legal actuation are likely similarly contingent on forms of participation in economic life. The potential for strategic legal behavior to influence tax liability, for example, could depend on the presence of taxable income or gains as well as eligibility for certain credits or deductions. The potential benefits to be gained from instances of legal actuation will also vary. Continuing with the example of tax-motivated behavior, the economic value of the benefit achieved through legal actuation could range from a few thousand dollars for being aware of and claiming the earned income tax credit (Internal Revenue Service 2023) to leveraging the law for massive income tax avoidance, such as when Peter Thiel proactively took advantage of the Roth IRA savings mechanism, designed to benefit middle-class retirees, to shield multiple billions of dollars from taxation (Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Callahan and Bandler2021). Because legal actuation is likely to involve situations where the law has been shaped to offer benefits to some groups, and those with power are more likely to be able to have shaped such benefits, we would expect that although opportunities for legal actuation are prevalent across all segments of the population, those who are economically advantaged will have more opportunities to engage in strategic transactional legal behavior.

Building on the evidence base regarding variation in reactive legal behavior, we would also expect that economically advantaged individuals will be more likely to successfully exploit opportunities for legal actuation. Legal needs surveys document that a significant proportion of people who experience a civil legal problem do nothing in response (e.g. HiiL and IAALS 2021; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2014), often because of a “lack of knowledge, time, money, or confidence.” (Pleasence and Balmer Reference Pleasence and Balmer2019a: 143; also see McDonald and People Reference McDonald and People2014). This is more common among those who are poor (HiiL and IAALS 2021) and can result from feelings of shame, insufficient power, fear, and frustrated resignation, often combined with resource constraints (Sandefur Reference Sandefur, Pleasence, Buck and Balmer2007). Moreover, those who do take action to resolve civil legal problems face several challenges, with the capability to successfully resolve problems unevenly distributed across the population (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Pleasence, Hagland and McRae2019), with a positive relationship between legal problem resolution and economic status (HiiL and IAALS 2021).

We would expect that the capability to engage in legal actuation will similarly increase with economic advantage. Indeed, indicators of economic advantage may be even more strongly positively correlated with legal actuation than with responsive legal behavior given the need to identify opportunities for strategic behavior. Justiciable situations that have risen to the level of “problems” have already been perceived by such as respondents; whether triggered by negative health, financial, or relational experiences, confrontation by the opposing party, or even legal action, justiciable problems have been “named” (Felstiner et al. 1980/Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980/1981). In contrast, there is likely greater variation in the rate at which individuals recognize and are empowered to act upon opportunities for instrumental ex ante legal behavior, such as using the law to maintain or build economic advantage.

Mechanisms of advantage in legal actuation

This begs the question, however, of how it is that economically advantaged individuals come to be able to engage in legal actuation. Because of the dual need to identify and act upon opportunities for instrumental civil legal behavior, some mechanisms that give rise to observed variation in other forms of individual legal behavior may be particularly salient in the context of legal actuation. In this article, we focus on three such mechanisms: legal socialization, knowledge, and capability.

Legal socialization

Deeply connected to the literatures on legal cynicism and legal consciousness (Swaner and Brisman Reference Swaner and Brisman2014), legal socialization refers to the “process by which people develop their relationship with the law” (Trinkner and Reisig Reference Trinkner and Reisig2021: 282). This relationship rests on attitudes and beliefs about the law, legal actors, and legal institutions that are formed through personal interactions with individuals connected to the legal system as well as family and other community members (Piquero et al. Reference Piquero, Fagan, Mulvey, Steinberg and Odgers2005). These beliefs are linked to evaluations of the legitimacy of the legal system and law-abiding behavior, making them consequential for social control and the rule of law (Tyler Reference Tyler1990). Together with studies of legal cynicism – or “‘anomie’ about law” (Sampson and Jeglum Bartusch Reference Sampson and Jeglum Bartusch1998:778) – most scholarship on legal socialization has a negative valence and focuses on the experiences of members of heavily-policed communities (e.g. Piquero et al. Reference Piquero, Fagan, Mulvey, Steinberg and Odgers2005; Ryo Reference Ryo2017).

In contrast, this article seeks to draw attention to legal socialization as a mechanism of advantage, particularly among members of economically privileged groups. That is, as economically advantaged individuals have positive experiences with law, they are socialized to see law as a beneficial and accessible resource, which can in turn increase their likelihood of engaging in legal action. This theory is bolstered by the finding that positive experiences with legal actors are associated not only with enhanced perceptions of the availability of legal expertise but the relevance of law for addressing everyday situations (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Pleasence, Hagland and McRae2019). The idea also finds commonality with at least one conceptualization of legal consciousness, which is theorized to represent a form of cultural capital (Young and Billings Reference Young and Billings2020). Bridging foundational work on legal consciousness (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998) and Bourdieu’s concept of habitus (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1984), Young and Billings (Reference Young and Billings2020) posit that class-based differences in beliefs and attitudes toward law can function as a mechanism of advantage, empowering socially advantaged individuals in law-related interactions. Building on this work, we posit that positive legal socialization will contribute to a sense of legal optimism that in turn makes economically advantaged individuals more likely to seek out, and act upon, opportunities for legal actuation.

Legal knowledge

In addition to this orientation toward law and its instrumental use, legal actuation also is likely a function of legal knowledge. As noted above, before individuals can actuate the law, they must first identify the possibility of doing so. Research on legal knowledge relating to justiciable problems finds that awareness of legal rights and processes varies by substantive area (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010; Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Balmer and Denvir2017). Even in areas that are among the most common sources of civil legal problems, there are many who lack awareness of their legal rights or the availability of legal assistance or procedures (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010; see also Legal Services Corporation 2017). For example, a nationally representative survey of legal needs in England and Wales found that among respondents who reported experiencing a problem with rental housing, one of the most common types of justiciable problems, 71% reported not knowing their legal rights in the situation and 75% reported that they did not know what legal processes were available (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010: 28).

Moreover, legal awareness is economically stratified, with those who have higher incomes more frequently possessing relevant legal knowledge (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Buck, Patel, Denvir and Pleasence2010). This is unsurprising given that many of the means through which individuals attain legal knowledge are also stratified, such as informal access to legal expertise (Cornwell et al. Reference Cornwell, Taylor Poppe and Doherty Bea2017) and use of lawyers (HiiL and IAALS 2021). Thus, we theorize that economically advantaged individuals are more likely to have greater legal knowledge and that this will contribute to increased levels of legal actuation.

Legal capability

Finally, a growing body of research highlights the importance of individuals’ legal capability, or “the personal characteristics or competencies necessary for an individual to resolve legal problems effectively” (Coumarelos et al. Reference Coumarelos, Macourt, People, McDonald, Wei, Iriana and Ramsey2012: 29). These internal capabilities, which include a combination of legal knowledge, confidence, attitudes, and skills (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Pleasence, McDonald and Sandefur2024), interact with structural forces to generate people’s opportunity to achieve satisfactory resolutions to legal situations (Habbig and Robeyns Reference Habbig and Robeyns2022). While researchers have long recognized the importance of legal capability (e.g. Parle Reference Parle2009; Pleasence et al. Reference Pleasence, Christine, Suzie and HM2014), advances in the measurement of this multidimensional phenomenon have deepened our understanding of its import (Balmer et al. Reference Balmer, Pleasence, Hagland and McRae2019; Legal Services Board 2020). This research finds that elements of legal capability differ with socio-demographic characteristics (Balmer and Pleasence Reference Balmer and Pleasence2018) including finding lower levels of legal capability among those with lower household incomes (Legal Services Board 2020). Individuals with greater legal capability exhibit different patterns of behavior in response to civil legal problems, making it more likely that they are able to access services and information needed to address their civil legal problems (Legal Services Board 2020). Extending this work, we expect that legal capability will be positively associated with economic status and with legal actuation.

Estate planning as legal actuation

This article investigates the relationship between economic advantage and legal actuation in the context of estate planning. Estate planning refers to the process of executing legal instruments during life that ensure that an individual’s preferences – regarding the administration and disposition of property and personal and medical care – will be carried out during periods of incapacity and at death. In addition, these instruments can nominate others to serve as fiduciaries (such as executor or trustee) responsible for carrying out the individual’s objectives.

Estate planning overview

Three categories of legal instruments are typically used in the estate planning context: wills, will substitutes, and powers of attorney. Wills are legal instruments used to dispose of property that is subject to the control of the probate court and typically identify an executor who will be responsible for administering the decedent’s estate. Will substitutes, such as trusts and beneficiary designations, direct the transfer of property outside of the probate court system, thus providing greater privacy and avoiding the costs and delay associated with the probate process. Finally, powers of attorney are used to appoint an individual who can make decisions – regarding either financial or health matters – for the benefit of another in the event of incapacity. Powers of attorney for health care are often combined with “living wills” to incorporate guidelines regarding the types of medical interventions that the executing individual is willing to receive. Together, these instruments enable individuals to satisfy personal preferences, direct support to those who are financially dependent upon them, ensure tax efficiency, optimize eligibility for government assistance, avoid court fees and other transaction costs, and express last wishes or sentiments (Friedman Reference Friedman2009; Sitkoff Reference Sitkoff2014).

Given the wide applicability of these benefits, there are few adults for whom estate planning offers no reward. Of course, the specific benefits generated by an estate plan will vary with individual circumstances.Footnote 1 Family structure, personal preferences, and the presence of minor dependents or intended beneficiaries are key factors (Bea and Taylor Poppe Reference Bea and Taylor Poppe2021). In addition, wealth – including both the value and types of assets an individual owns – is also relevant. However, wealth does not necessarily operate in the way that many people assume.

In contrast to the popular assumption that only those with significant wealth benefit from having an estate plan, estate planning actually may be more consequential for those with less wealth. For example, misalignment with the laws of intestacy that control distribution in the absence of an estate plan is more prevalent among those with less wealth (Bea and Taylor Poppe Reference Bea and Taylor Poppe2021). And, in families where there is greater financial need among beneficiaries, inheritance that is modest in absolute terms may have a significant effect on recipients. In addition, the fractionation of land interests under intestate succession is a problem that can be particularly consequential for lower income individuals and communities (e.g. Mitchell Reference Mitchell2014).

Thus, estate planning is a valuable setting in which to study legal actuation because the need for estate planning instruments – and thus the opportunity for instrumental transactional legal behavior – is widespread across the population. In addition, estate planning forms part of the broader set of legal processes through which the transfer of material wealth at death is facilitated, and which is essential to the intergenerational transmission of wealth and the perpetuation of economic inequality.

Variation in estate planning actuation

Estate planning is a domain characterized by economic stratification. At one end of the spectrum, many economically advantaged families behave strategically during life to minimize taxes at death so that more wealth may be transferred to younger generations, as well as lobbying for higher exemptions and lower rates for federal taxes imposed on the transfer of wealth (Lincoln Reference Lincoln2006). For example, high-net-worth families use annual exemptions from gift tax to transfer thousands of dollars each year free of transfer taxes to each member of their family (Senate Finance Committee 2017). They structure the ownership of family-held assets to reduce their valuation for tax purposes (Hemel and Lord Reference Hemel and Lord2021) and use grantor trusts to transfer appreciating assets with little or no tax liability (Ernsthausen et al. Reference Ernsthausen, Bandler, Elliott and Callahan2021). By shifting trusts across jurisdictional lines, they shield them from creditors and extend control over trust assets in perpetuity (Sitkoff and Schazenbach Reference Sitkoff and Schazenbach2005).

Moreover, these activities are in addition to basic forms of estate planning undertaken to ensure that assets are distributed at death in accordance with individuals’ preferences, quickly and with minimal disruption for surviving family members. These estate plans also provide private mechanisms for transferring control over individuals’ health and finances during periods of incapacity. An entire professional industry of lawyers, investment managers, banks, trust companies, and family offices manage these transactions and address the needs of these individuals (Scheiber and Cohen Reference Scheiber and Cohen2015; Winters Reference Winters2011).

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the tens of millions of adults in the United States who lack even a will (Jones Reference Jones2021). Any property of theirs not subject to an alternate transfer or ownership arrangement is distributed at death to their legally recognized kin as mandated by the laws of intestacy in their state of domicile (for a 50-state survey of intestacy laws, see Schoenblum Reference Schoenblum2021). This occurs without regard for their financial or personal circumstances or their individual preferences. Plus, the process plays out in public in state probate courts, which impose financial cost, delay, and administrative burden. By failing to engage in estate planning, individuals also forego the opportunity to appoint others to positions of trust, such as executor or guardian for minor children. These kinds of instructions – as well as information regarding preferences for the allocation of property – can help to promote family harmony and ease the administrative burden on surviving family members (Cahn and Zeittlow Reference Cahn and Zeittlow2015).

Despite the widespread need for estate planning, extant research finds economic variation in the rate at which individuals undertake this instrumental legal behavior. Prior research on inequalities in estate planning has primarily focused on the use of wills, and consistently finds a positive relationship between indicators of economic status and testacy (for a review, see Taylor Poppe Reference Taylor Poppe2020).Footnote 2 There is also evidence that less economically advantaged individuals are more likely to forego the chance to express binding preferences regarding end-of-life medical care or the disposition of the body or to appoint others to make decisions on their behalf (e.g. Carr Reference Carr2012; Khosla et al. Reference Khosla, Curl and Washington2016; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Anderson, Feng-Chang and Laux2014).

The strength of the correlation between economic status and each form of estate planning is likely to differ, given differences in the relative accessibility of the legal instruments. For example, powers of attorney are widely – if not universally – beneficial and can be established using freely distributed standardized forms. Thus, we would expect that markers of economic advantage are less strongly linked to their usage. In contrast, instruments like trusts require greater customization and are less easily self-drafted, leading us to anticipate greater social stratification in their usage. Yet, in each case, there is reason to expect that economic advantage will continue to relate to an increased likelihood of legal actuation. Moreover, because estate planning documents are often prepared together, there are likely carryover effects that increase the likelihood of multiple forms of estate planning for those who engage in any form of estate planning (Carr Reference Carr2012).

Mechanisms of estate planning actuation

We know much less about the mechanisms that generate these results. Self-selection into estate planning is often attributed to variation in individuals’ perceived need for estate planning or the anticipated benefit of estate planning relative to its cost. However, these ideas hint at deeper mechanisms at play – those that give rise to the beliefs and knowledge that underlie these assessments.

Building on the theoretical work above, we posit that as with other forms of legal actuation, legal socialization, legal knowledge, and legal capability regarding estate planning will be socially patterned and that these mechanisms will predict inequalities in estate planning actuation. More specifically, given the strong ties between estate planning and wealth, we anticipate that each of these mechanisms will be positively associated with wealth, that they will predict variation in estate planning, and that these dynamics are like to be particularly pronounced for forms of estate planning that are less widely accessible.

At the same time, because these mechanisms are distinct from wealth, we expect they may also operate independently. For example, an individual could witness the provision of care or the distribution of assets in accordance with a decedent’s wishes due to successful estate planning, or could witness the opposite in the absence of legal actuation (Carr Reference Carr2012). Both experiences may generate legal knowledge about the role of estate planning and increase the likelihood of undertaking proactive legal behavior. As a result, we also expect that within wealth categories, these mechanisms will be positively associated with the likelihood of having estate planning instruments.

Data and analysis

Data

To address these topics, we rely on novel survey data on estate planning utilization generated through an online survey administered by Qualtrics (N = 1,955).Footnote 3 The sample is consistent with the national population distribution by age, race and ethnicity, education, and income (Taylor Poppe Reference Taylor Poppe2020). The survey was fielded in 2019 prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, thus avoiding period-specific effects resulting from the pandemic. It included questions about the use of several types of estate planning instruments, their preparation, reasons for undertaking or foregoing estate planning, as well as demographic information. The data were used to generate the following variables used in the analysis.

Legal actuation

To measure respondents’ legal actuation, our outcome of interest, we use a series of variables indicating whether respondents report having a will, a trust, a power of attorney for finances, or a power of attorney for healthcare.Footnote 4 Because a comprehensive estate plan would likely include all of these instruments, we also generate a variable identifying respondent who report having a will, a trust, and both powers of attorney.

Legal socialization

Legal socialization, one of the three mechanisms we propose will shape actuation, is measured with a three-level summary variable based on indicators of familial exposure to estate planning and personal experience with estate administration. Respondents with no observed legal socialization indicated that they did not have a parent or grandparent with a will and had no experience with estate administration. Those with the greatest legal socialization indicated that they had both a parent and grandparent with wills and also had experience with estate administration. Respondents with some socialization had either at least one ancestor with a will or had experience with estate administration but did not have all of these experiences. Our measure of legal socialization does not distinguish between informal experiences of estate administration (e.g. observing the administration of an estate) and formal experiences (e.g. being named executor of an estate). Either experience exposes the individual to the process of estate administration.

Legal knowledge

Legal knowledge, our second mechanism, is measured using the response to a multiple-choice question that asked respondents to select the option that indicated what would happen to their property at death if they died without a will. Respondents can be divided into three groups: those who correctly identified how property is allocated at death in the absence of a will; those who selected a substantive response that incorrectly described how property is allocated at death for intestate decedents; and those who indicated that they did not know. While only those in the first group exhibited actual legal knowledge, those in the first two groups may be categorized as exhibiting perceived legal knowledge. Providing a substantive response likely indicates some degree of knowledge about estate law, in contrast to the third group that explicitly reports a lack of knowledge. Because we are more concerned with how perceived – as opposed to actual – legal knowledge motivates legal actuation, the legal knowledge in the primary analysis identifies those respondents who indicated that they did not know how property is allocated at death in the absence of a will; to make interpretation more intuitive, the variable is reverse-coded (0 = don’t know, 1 = substantive response). However, in supplemental analysis in Appendix 2, we also report results distinguishing across all three categories of legal knowledge.

Legal capability

Legal capability, our third mechanism, is measured using a validated scale of general legal confidence developed by Pleasence and Balmer (Reference Pleasence and Balmer2019b). Respondents were presented with a prompt that asked them to indicate “how confident are you that could achieve an outcome that is fair and that you would be happy with” for six items that describe situations that might occur in response to a common civil legal problem. Each item involves an escalation in the situation, from the initial item where “disagreement is substantial and tensions are running high” to the sixth item where “the court makes a judgment against you” and the respondent is faced with the possibility of needing to file an appeal. For each question, individuals indicate their level of confidence on a four-choice scale from very confident to not at all confident. These responses are aggregated and raw scores are scaled (0–100) following Pleasence and Balmer (Reference Pleasence and Balmer2019b), where a higher score indicates higher legal capability.

Wealth

Wealth is our final key independent variable of interest and is indicated with a variable generated using two questions modeled on items on the Survey of Consumer Finances. The first question asks individuals to assess whether they have negative, zero, or positive wealth (that is, whether their assets are greater than, equal to, or less than their liabilities). Those respondents who indicate that they have positive wealth are then asked to identify the bracket into which their wealth falls. The analyses use a four-category measure of wealth indicating negative wealth, zero wealth, positive wealth that is less than $150,000, and wealth of at least $150,000.Footnote 5

Additional socio-demographic variables

Because estate planning is known to vary across other socio-demographic factors, several other individual characteristics are included in the analysis. Gender is measured with a variable indicating self-reported female gender (1 = female, 0 = male).Footnote 6 Race and ethnicity is indicated with a five-category variable indicating Latino or non-Latino White, Black, Asian, or other. Data on age was collected using year of birth. Education is measured using a categorical variable indicating whether the respondent has less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma, some college, a college degree, or graduate education. Current marital status indicates whether respondent reported being married, widowed, divorced (including those who were separated), or never married. The parent variable indicates whether the respondent reported having any children.

Analysis

Prior work using these data reported the percent of respondents with each type of estate planning instrument and also offered evidence of variation in the probability of having a will based on individual characteristics including wealth (Taylor Poppe Reference Taylor Poppe2020). This article moves beyond these findings by investigating several mechanisms that could generate the observed variation in estate planning by wealth and by considering the effect of these mechanisms across multiple estate planning instruments. More specifically, it explores how legal socialization, legal capability, and legal knowledge vary with wealth, and analyzes whether these mechanisms are positively associated with the probability of having a will, a trust, a power of attorney for health or finance, or a comprehensive estate plan with all of these instruments. This analysis is not able to identify a causal relationship between these mechanisms and estate planning uptake, but instead offers an exploratory first step toward understanding potential causes of observed socio-economic variation in estate planning legal actuation.

Findings

Summary statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the full sample and for the subsamples of individuals with each type of estate planning instrument and those with all instruments. Forty-three percent of the sample reports having a will, in line with prior work indicating that fewer than half of Americans are testate (e.g. Jones Reference Jones2021). About the same share (44%) report having a power of attorney for health, while 37% report having a power of attorney for finances. Just 26% report having a revocable trust, and fewer than one in five respondents report having all four instruments (19%). Individuals reporting having one or all of these instruments are disproportionately married and parents, with higher levels of education. They also tend to have relatively high levels of wealth; for example, just 7% of will holders have negative wealth while 50% report wealth of at least $150,000.

Table 1. Summary statistics, for the full sample and by estate planning instrument

Our mechanisms of legal actuation also vary across these groups. The subsample of respondents with each estate planning instrument or all instruments have a greater proportion of respondents who reported answering the legal knowledge question as opposed to saying “I don’t know.” In terms of legal socialization, over half of all respondents report having one ancestor with a will and/or experience with estate administration, but higher levels of legal socialization are more prevalent among those who have undertaken estate planning. Perceived legal capability, as measured through the six-item scale of confidence in resolving legal issues, is also relatively high among individuals with estate planning instruments, ranging from 65 to 72 on the 100-point scale.

Figures 2–4 investigate descriptively the relationship within each wealth category between estate planning and legal knowledge, legal socialization, and legal capability, respectively. Even as Table 1 shows a positive association between net worth and estate planning for each instrument type, these figures show that the mechanisms of legal actuation vary within wealth categories and are associated with higher rates of legal actuation for each instrument. For example, the top-left panel of Figure 2 shows that the proportion of individuals with a will is generally highest among those with at least $150,000 in wealth, but also that there is variation within this wealth category by legal knowledge. Nearly 74% of individuals who provided an answer to the legal knowledge question have a will in this wealth category, compared to just over 50% of high-wealth individuals who answered “I don’t know.”

Figure 2. Rate of estate planning by legal knowledge and wealth, for each instrument.

Figure 3. Rate of estate planning by legal socialization and wealth, for each instrument.

Figure 4. Average legal capability score by estate planning uptake and wealth, for each instrument.

This within-wealth variation is consistent across our three proposed legal actuation mechanisms. Those with the highest levels of legal socialization (Figure 3) consistently make up the greatest share of individuals with each estate planning instrument, within each wealth category. For example, among individuals with zero wealth, 70% of individuals who have an ancestor with a will and have engaged in estate administration have a will, compared to just 35% of individuals with some form of legal socialization and 18% of individuals who have no form of socialization (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows that within each wealth bracket the average legal capability score is higher among those who hold each instrument compared to those who do not. For example, the top-right panel shows that among individuals in the highest wealth category, the average legal capability score is less than 60 for non-trust holders but over 70 for those with trusts (Figure 4).

Regression analysis

We next turn to our modeled results. Appendix Table A1 provides estimated coefficients from a series of models predicting the probability of having each estate planning instrument and all instruments using our mechanisms and including controls for wealth and other socio-demographic characteristics. Figures 5 and 6 present results derived from the full models in Appendix Table A1. These figures present the predicted probability of having each estate planning instrument, by legal actuation mechanism. Legal capability, a continuous measure, is presented at representative percentiles (25th, 50th, and 75th percentile). We generate these results using the Stata margins post-estimation command, keeping all variables as observed. Though results for each mechanism are presented in their own panels, these mechanisms are jointly estimated in the same model, as shown in Appendix Table A1. For example, the results in the first panel of Figure 5 show the predicted probability of having a will by each level of legal socialization, net of legal capability and legal knowledge and the full set of controls.

Figure 5. Predicted probability of having a will, by actuation mechanisms.

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities of having a trust, powers of attorney, and full plan, by actuation mechanisms.

Appendix Table A2 confirms that the important distinction is perceived legal knowledge rather than actual legal knowledge. Although there are some significant differences in the probability of having an estate planning instrument between individuals who correctly identify what happens to a person’s property if they die without a will compared to those who answered incorrectly, the magnitudes of the difference are about half that of the difference between those who answered incorrectly and those who replied “I don’t know.” In other words, even individuals who failed to accurately summarize how the law handles intestacy were more likely to have engaged in estate planning than those who indicated that they did not know what would happen.

Figure 5 illustrates that all three mechanisms are positively associated with the predicted probability of having a will, with more socialization, knowledge, and capability resulting in higher predicted probabilities of having this instrument. Of the three, legal socialization has the strongest association: those with both an ancestor who had a will and direct experience in managing an estate have a predicted probability of 0.6 (p < 0.001) compared to those with neither, who have a probability of 0.3. Differences across levels of knowledge and capability are more modest, but are all statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Similar figures showing the predicted probability of having a trust, powers of attorney, or all instruments are shown in Figure 6. The findings are consistent with those for having a will: after adjusting for all other variables, legal socialization, legal knowledge, and legal capability are positively, and largely significantly, associated with the predicted probability of having each instrument. Of the three mechanisms, having all observed forms of legal socialization consistently results in the highest predicted probability, net of the other mechanisms and key demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Within-wealth differences in actuation

The above results show that legal socialization, knowledge, and capability are each associated with the likelihood of having one or more estate planning instruments, and that this true even after adjusting for wealth. We next evaluate whether these mechanisms contribute heterogeneity in the probability of having an instrument within wealth categories to better understand whether these mechanisms are a proxy for wealth or exhibit independent effects. To simplify analyses, we limit our focus to wills.

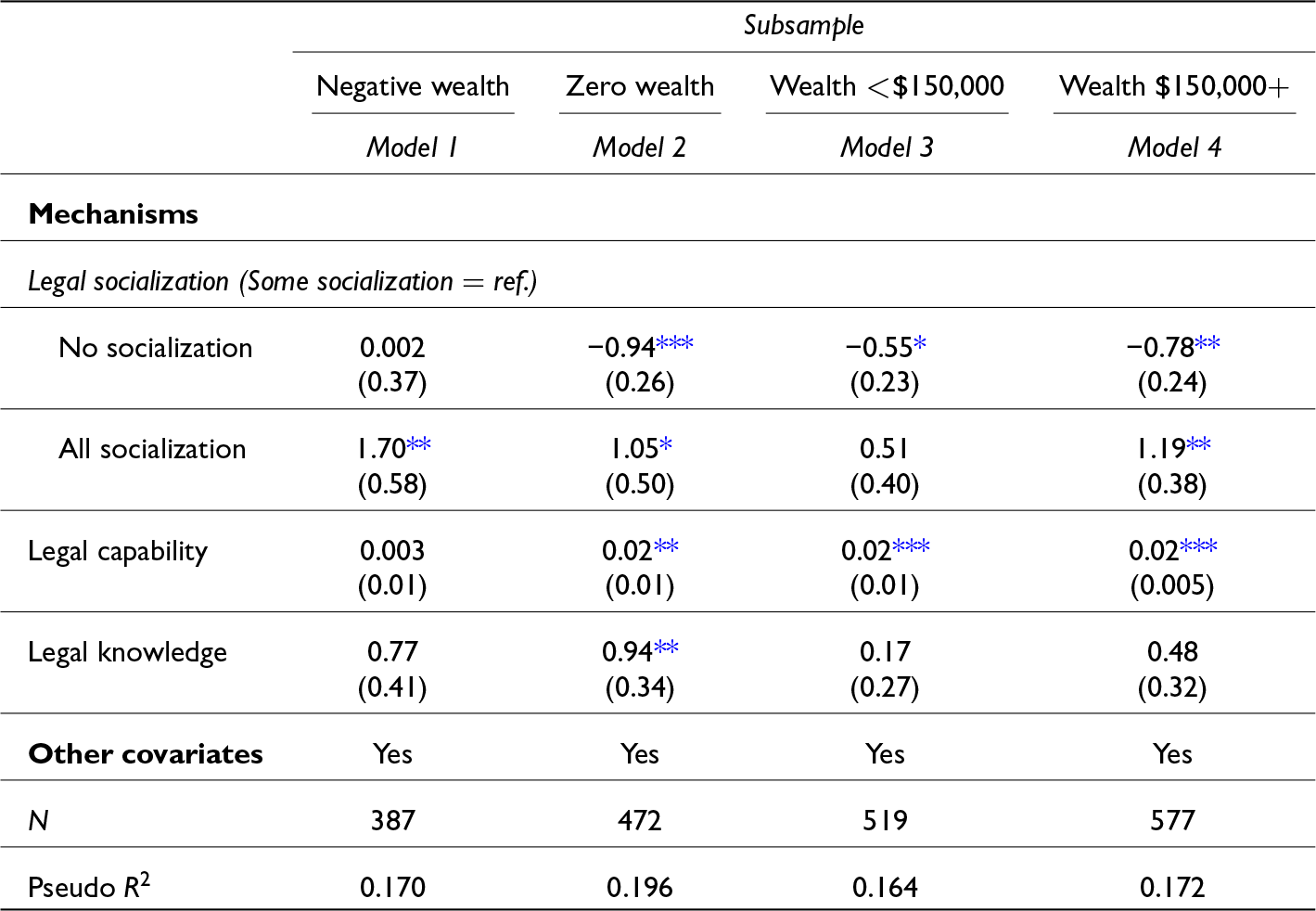

Table 2 provides estimated coefficients from models predicting the probability of having a will among respondents within each wealth category, net of all other socio-demographic controls. Because of the reduction in sample size, some uncertainty regarding the estimates is to be expected. Yet, as with the main results, we find that legal socialization is consistently associated with an increase in the probability of having a will, and this is largely true across all wealth categories. For example, relative to the reference category of some socialization, individuals with no socialization are largely less likely to have a will and those with all forms of socialization are more likely to have a will. For each wealth category, these differences are largely significant. The two exceptions are (i) individuals with negative net wealth, where individuals with no socialization and some socialization are equally as likely to have a will, and (ii) individuals with wealth under $150,000, where there is no significant difference between the reference category and those with the other levels of socialization.

Table 2. Estimated coefficients and standard errors from models predicting probability of having a will, for each wealthcategory group

* p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Note: Models also control for legal socialization, legal capability, wealth, race and ethnicity, age, age squared, sex, education, marital status, and parental status; N = 1,955.

Results for the other two mechanisms are more mixed. While an increase in legal capability is associated with an increased probability of having a will for all wealth categories, we lack evidence that this association is statistically significant for those with negative net wealth. Legal knowledge is associated with a positive and significant increase in the probability of having a will for those with zero wealth; while the coefficients remain positive for the remaining groups, they fail to achieve statistical significance. Overall, this offers evidence that these mechanisms are associated with differences in the probability of estate planning apart from the operation of wealth, but also suggests that these mechanisms are most impactful at higher levels of wealth where the overall prevalence of estate planning is higher.

Discussion and conclusion

This study breaks new ground by revealing how proactive and instrumental legal behavior, which we call legal actuation, shapes economic inequality. Using the law to build or maintain economic advantage requires that individuals know when and how to leverage those laws. We offer evidence of three key mechanisms that help to facilitate this process. Using a case study of estate planning behavior, our findings indicate that legal socialization, legal knowledge, and legal capability – all of which are positively correlated with wealth – are associated with an increase in the likelihood of estate planning. Our results remain descriptive and more research is needed to understand how legal actuation may contribute to inequality.Footnote 7 Nevertheless, our study highlights an important but understudied way in which ex ante legal behavior fosters economic advantage.

The article makes several contributions. First, the article develops the theory of legal actuation. By naming and defining this phenomenon, the article draws attention to advantageous legal engagement that may be occurring in a range of legal domains. This offers an important contrast to extant bodies of work focused on the detrimental effects of legal entanglement and represents a further dimension of cumulative advantage. This points to new areas of inquiry that could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the ways in which law reifies social stratification.

Recognition of legal actuation as fostering unequal outcomes under law also raises important concerns regarding equal justice. Hadfield (Reference Hadfield2010) highlights the relative lack of ex ante legal resources for individuals and emphasizes the role of professional legal regulation in distorting the market for these services (Hadfield Reference Hadfield2017). Increasing pressure on the legal profession’s regulatory created monopoly on the provision of legal advice and the rise of generative AI bring urgency to these questions. By emphasizing variation in legal actuation as a barrier to equality under the law, this article challenges more conservative notions of access to civil justice that remain fixated on ex post responses to legal problems.

As part of our theoretical contribution, we also highlight three mechanisms of legal actuation, each of which can be measured, operationalized, and tested in quantitative studies. Legal socialization, which has primarily been studied as a mechanism of disadvantage, is instead shown here to be a tool for transmitting advantage across generations. This extends existing scholarship and raises important questions about the ways in which socially advantaged individuals encounter law and how learnings from these encounters are internalized and shape future behavior. Legal knowledge, while long a concern among scholars focused on ways to increase access to civil justice (e.g. Denvir et al. Reference Denvir, Balmer and Pleasence2013), has not been a primary focus among law and society scholars. Yet, our work indicates that perceived knowledge of law on the books can have implications for law in action, suggesting the need for further exploration of the ways in which legal information is transmitted and extending scholarship on legal expertise as a form of capital (e.g. Cornwell and Cornwell Reference Cornwell and Cornwell2008). Notably, we find that perceived knowledge matters as much, and possibly more than, actual knowledge of law on the books. This underscores the importance of understanding the roles of confidence and knowledge in shaping legal actuation. Finally, we investigate the role of legal capability in shaping outcomes in a transactional, ex ante context, furthering emerging access to justice scholarship focused on responses to civil legal problems.

In addition, this research invites investigation into the relationship between legal consciousness and legal actuation. This has the potential to provide an important comparative perspective to existing scholarship that evaluates how conceptualizations of legality both shape reactive legal behavior and maintain law’s hegemony despite its many failings (Silbey Reference Silbey2005). Law and society scholars can use the concept of legal actuation, the three mechanisms we explore, and existing theories of reactive legal action to consider legal behavior that may preempt or protect individuals from future justiciable problems, as well as legal behavior in contexts where there are not “problems” but rather opportunities for legal advantage.

Our study also complements research on legal mobilization and other work focused on the relationship between power and the design of laws. It offers an essential piece of the analytic puzzle of how power and law interact, emphasizing that not only do individuals and groups work to change law, but must also work within the system created. Our case of estate planning considers only legal forms of legal actuation, but the framework of legal actuation may be extended to consider situations where economically advantaged individuals identify legal loopholes or transgress the boundaries of accepted behavior in ways that further build wealth. An expose of the Trump family’s wealth transfer mechanisms, for example, highlighted not only tactics that are legal and commonly used by many wealthy families but also allegations of fraud and tax evasion (Barstow et al. Reference Barstow, Craig and Buettner2018). Insider trading and collusive anticompetitive business practices are other areas where knowledge of law and the scope of enforcement may allow advantaged parties to engage in legal actuation to break the law “safely.” Future research using the framework of legal actuation with these three mechanisms could potentially reveal the processes through which individuals are able to “play the law” in ways that result in illegal gains that rarely become justiciable problems for them.

Finally, the study draws attention to estate planning as an important but relatively understudied legal behavior with important implications for the transmission of wealth. Wealth inequality literature highlights the concentration of advantage at the top (e.g. DiPrete and Eirich Reference DiPrete and Eirich2006; Keister and Young Lee Reference Keister and Young Lee2014; Piketty Reference Piketty2014); legal actuation provides an explanation of how the optimization of legal behavior is economically stratified in ways that contribute to this concentration. We find that wealth is positively associated with higher levels of legal socialization and knowledge when it comes to estate planning topics. In turn, these mechanisms are associated with an increased probability of having estate planning instruments that facilitate the transmission of intergenerational wealth. As noted at the outset, the laws of succession are essential to perpetuating economic inequality, and behavior leveraging these laws to preserve advantage is integral to the stability of the current economic structure. Moreover, although our focus is on economic advantage, the laws of succession can also reinforce other forms of subordination (Cahn Reference Cahn2019; Crawford and Infanti Reference Crawford and Infanti2014). Future work integrating feminist and critical insights could provide a richer, more intersectional understanding of the ways that legal actuation exacerbates inequality.

In addition, understanding how and why individuals engage – or fail to engage – in estate planning also has important policy implications, for people across the wealth spectrum. The laws of succession often incorporate empirical assumptions about the identities, characteristics, and preferences of those who engage in estate planning and could be enhanced with a deeper theoretical and empirical understanding of estate planning behaviors (Taylor Poppe Reference Taylor Poppe2021). Understanding these dynamics could also inform the design of interventions to increase the access and use of estate planning. Knowing that legal socialization, knowledge, and capability are associated with increased probabilities of estate planning within wealth groups motivates the development of legal education around estate planning. For example, interventions that encourage end-of-life health planning among older adults (Carr and Luth Reference Carr and Luth2017) could be expanded to address financial aspects of estate planning. Public education initiatives could also be expanded to other legal domains that individuals may encounter in daily life. For example, state-mandated financial literacy programs in high schools are increasingly common and are associated with positive financial outcomes in later life (Urban et al. Reference Urban, Maximilian Schmeiser and Brown2020); meanwhile, know your rights civic education programs seek to empower people to engage with law to solve problems. Including domains that bridge finance and law, like estate planning, as part of these education efforts may increase general legal knowledge and capability in ways that increase proactive, ex ante legal behavior.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1. Estimated coefficients and standard errors from logistic regression models predicting estate planning

* p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Note: Models also control for legal socialization, legal capability, wealth, race and ethnicity, age, age squared, sex, education, marital status, and parental status; N = 1,955.

Appendix Table A2. Estimated coefficients and standard errors from logistic regression models predicting estate planning, using alternate coding for legal knowledge

* p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Note: Models also control for legal socialization, legal capability, wealth, race and ethnicity, age, age squared, sex, education, marital status, and parental status; N = 1,955.

Emily S. Taylor Poppe is professor of law at the University of California, Irvine School of Law and faculty director of the UCI Law Initiative for Inclusive Civil Justice. She holds a PhD in sociology from Cornell University and a JD from Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. Her research investigates inequalities in access to civil justice, including in the trusts and estates context.

Megan Doherty Bea is an assistant professor of Consumer Science in the School of Human Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She holds a PhD in sociology from the Cornell University. Her research examines the causes and consequences of socioeconomic and financial inequalities the United States.