INTRODUCTION

Trademark law was one of the legal appearances of the Second Industrial Revolution of the late nineteenth century (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2010). The empires of the time incorporated trademark law in their imperial checklist and imposed it in various colonies, protectorates, and, in the aftermath of the First World War, in mandates as well. Trademark law protects distinctive commercial names and signs of products against unauthorized use. It is a legal tool for conveying information about the origin of goods to consumers. The dominant approach is that of economic analysis (Landes and Posner Reference Landes and Posner1987). Manufacturers may apply to the national trademark office to register their marks. Registration is voluntary and provides legal protection of the mark.

Other than the market function, trademarks are signs. In linguistic terms, they are composed of a signifier and a signified (Culler Reference Culler1986). Thus, trademarks are carriers of cultural information about the manufacturers, their products, and their message to the consumers. Each trademark captures a particular manufacturer-goods-consumer relationship. Aggregating trademarks from a defined time and place provides a trademark mosaic, offering a fresh perspective of a society and its economy and of the players and their ideologies. However, trademark registries are as yet understudied.

The current study tells the sociolegal history of trademark law in Mandate Palestine (1917–48) by exploring trademark data and by offering a semiotic analysis of local applications. During this period, 7,263 trademarks were registered under the British trademark system; 1,590 of which were submitted by residents of Mandate Palestine, both Jewish and Arab. This study has empirical and semiotic prongs. While patent registration has been subject to numerous, mostly economic, studies (for example, Karki Reference Karki1997), and copyright registrations have only recently been subject to empirical studies (Brauneis and Oliar Reference Brauneis and Oliar2018, 46–98; Rosen and Schwinn, Reference Rosen and Schwinnforthcoming), trademark registries have attracted scant attention and even less so in historical studies (Çela Reference Çela2015). Thus far, such attention has come almost only from business historians (da Silva Lopes and Duguid Reference Da Silva Lopes and Duguid2010; Llonch-Casanovas Reference Llonch-Casanovas2012; Sáiz and Pérez Paloma Reference Sáiz and Pérez Paloma2012). The current study illustrates the potential of trademark data for legal historians. Studying the trademark data from Mandate Palestine immediately indicates a sharp division between Jewish-Zionist traders and manufacturers, on the one hand, and Arab-Palestinian ones, on the other. Whereas the former embraced the British system within a few years, the latter adopted it only in a limited manner. Importantly, this does not mean that the Arab traders did not mark their products, as there was no legal obligation to register product names with the government, but it does indicate that, by and large, they rejected the foreign, capitalist system of trademark law.

The semiotic analysis examines the trademarks themselves, seeking to decipher their meaning at the time. It shows that some Jewish traders used trademarks for conveying national Zionist messages, whereas the Arab traders used cultural signifiers and, occasionally, religious symbols, but hardly any with direct national meanings. Amanda Scardamaglia (Reference Scardamaglia2015, x), in a pathbreaking exploration of trademark history in colonial Australia, aptly described the goal of semiotic analysis as uncovering the “narratives that emerge from colonial trade marks themselves, as symbols of colonial identity and which speak to the very fabric of colonial people, power, and place.” In the case of Mandate Palestine, the cultural content was fueled with issues of nationality.

The current discussion adds another chapter to trademark history; it illustrates the value of analyzing trademark data along a semiotic analysis and argues that the national angle should be added to the cultural perspective. Finally, it provides yet another patch to the legal history of Mandate Palestine (Likhovski Reference Likhovski2006). The article begins with the legal history of British trademark law in Mandate Palestine. It continues by exploring the trademark data. As the original trademark registry has not survived, I have reconstructed the registry from the trademark applications published in the Official Gazette, as explained below. The final part offers a semiotic analysis of local trademarks characterized by graphical content, as registered by local Jewish and Arab applicants. The common thread of these three inquiries is that of nationality.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

The study applies a cultural critical legal history perspective, with empirical and semiotic components. Viewing trademark history through a cultural lens reflects the role of trademarks as carriers of cultural and social meanings. The critical approach to trademark law has produced an important body of literature, treating trademarks as culturally embedded signs (for example, Coombe Reference Coombe1990; Dreyfuss Reference Dreyfuss1990; Pollack Reference Pollack1993; Beebe Reference Beebe2004). Identity politics has had some prominence in the trademark literature, such as addressing sexual identity (Sunder Reference Sunder1996), ethnic minorities (Matal v. Tam 2017), and race (Hinrichsen Reference Hinrichsen2012).Footnote 1 Missing from this literature is nationality. Unlike copyright law history, trademark law history has thus far attracted scant scholarly attention (Sherman and Bently Reference Sherman and Bently1990). The few available works are relatively descriptive and uncritical, focusing on the law in Western economies. The first wave of legal histories of trademark law pointed to ancient practices of using marks, such as marking cattle and pottery (Roger Reference Roger1910; Greenberg Reference Greenberg1951; Ruston Reference Ruston1955; Diamond Reference Diamond1975, 266–72), even going back to the biblical story of Cain (Greenberg Reference Greenberg1951), then progressing from ancient times through the Middle Ages to the law at the time of writing. The chronological accounts create an impression of a linear development from a primitive system where an individual decided for himself to use a mark to a sophisticated, state-run registration system.

The major change in trademark use transpired in the nineteenth century. Sidney Diamond (Reference Diamond1975, 280–81) pointed to several factors that brought about the change: modern manufacturing methods replaced handwork; production was concentrated in larger units, which required developing methods of distribution; and advertising was introduced to acquaint the public with the goods, precipitating trademarks to identify the source of the goods. The demise of the guild system in the Middle Ages should be added to these developments, opening markets to competition. Thomas Drescher (Reference Drescher1992, 321–24) adds the “environment of global markets, free competition and mechanized production,” especially highlighting advertising, which enabled the creation of a “product identity.” These explanations fit the market functions theory of trademark law and explain the timing of the arrival of the first modern trademark laws, both in the UK (1875) and the US (1870, 1881).Footnote 2 In the colonial context, few historical accounts addressed trademark law, with the exception of the self-governing dominion of colonial Australia (Scardamaglia Reference Scardamaglia2015). The current discussion explores Mandate Palestine, which involved a different mode of British colonialism.

The legal historian lens denotes that the present discussion is framed within the context of Mandate Palestine and its political and economic complexities, notably the transition from a pre modern economy with traditional industries to a modern, industrial one. This article conceptualizes the introduction of trademark law in Mandate Palestine as a legal transplant (Watson Reference Watson1974), but it does so with a critical lens—namely, the discussion goes beyond mere observation of the transplant and views it as a process (Theoretical Inquiries in Law 2009; for the application in copyright law, see Birnhack Reference Birnhack2012). The task is to search for divergences between the foreign, colonial law and its local incarnations, which often contain telling information about the transplantation process. A full inquiry would begin with the British motivation in extending trademark law to Mandate Palestine in the first place and trace the legal and political process of doing so. Here, I focus on the final stage of this process, the reception of the law by the local residents.

TRADEMARK LAW IN MANDATE PALESTINE

Colonial trademark law was rarely applied as is; rather, it morphed into the legal and cultural space and came to bear local meanings, reflecting a typical process of legal transplantation. A concise context is in place, yet inevitably delivered in broad strokes. Mandate Palestine was the region comprising today’s Israel, excluding the Golan Heights but including the West Bank and Gaza, when it was under British rule. In 1922, the League of Nations entrusted the King of England with a “Class A” Mandate for Palestine. In that same year, Jews in Palestine accounted for only 11 percent of the population (84,000 Jews; 668,000 Arabs). By 1940, the Jewish population had reached 31 percent. Whereas the Arab sector experienced a continuous process of urbanization, most of the population lived in rural villages (64 percent in 1946).

Jewish immigration was one of the most heated issues of the time. Following two earlier waves of immigration (Aliyah) under the Ottoman rule, Jewish immigration during the British period increased, followed by increased tensions between Arabs and Jews, with violent events occurring in 1921 and 1929. The spring of 1936 brought about a six-month Arab general strike, evolving into the three-year Arab Revolt, characterized by daily, countrywide violent events. During this period, the Jewish and Arab economies diverged, with fewer Arabs working for Jewish employers and a decrease in cross-national trade. Following the United Nations’ 1947 Partition Plan for Palestine, a civil war broke out, continuing with the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and a regional war.

During the mandate, Palestine’s economy shifted from being traditional to being modern. Following the First World War, which left the region in devastating circumstances, the British and the locals actively engaged in rebuilding the country and modernized it. The population increase, the immigrants’ capital, and foreign Jewish investments enabled the building of new towns and villages on a massive scale as well as the increase of agriculture and industry. During some years of the mandate, Palestine’s economy enjoyed the highest economic growth rates in the world (J. Metzer Reference Metzer1998, 25). To better understand the working of trademark law in Mandate Palestine, I point to three aspects of its economy that might explain why trademark law was used, how it was used, and by whom.

First, the shift to an industrial economy changes the producer-consumer relationship. In a premodern economy, such interactions take place in small, self-contained markets where the products are handmade or grown and are sold by the producer directly to consumers. The producers-sellers and the consumers are repeat players and know each other personally. The ongoing relationship guarantees the consumer’s familiarity with the products’ origin, making consumer confusion unlikely. Under such conditions, there is little need for an intermediating mechanism between producers and buyers. By contrast, in a modern economy, products are mass-produced, usually by corporations, often far away from the point of sale or even abroad. The consumer no longer knows the producer in person. In the absence of direct interaction, there is a need to convey information about the product, build trust, and create an enduring relationship. Thus, the direct sale is replaced with an intermediated one via traders and retailers. Without marking the origin, consumers are likely to bear high search costs in reexamining the product each time anew, and the producer is less likely to care about maintaining the product’s quality. Trademark bridges this gap: it indicates the product’s origin and thus vouches for its quality. Almost a century ago, scholars aptly described the first commercial uses of trademarks by firms as “reaching their hands over the retail tradesman’s shoulder, and offering their goods in their own name to the customer” (Schechter Reference Schechter1927, 818).

Palestine’s economic shift to a capitalistic mode began in the mid-nineteenth century but was almost entirely based on the export of agricultural products, such as wheat, barley, dura, sesame, oil, oranges, and cotton (Schölch Reference Schölch1981). Such products often served as raw material for other products and were delivered in bulk rather than in packaged form with a trademark attached. Industrialization accelerated during the mandate and was faster in the Jewish sector than in the Arab one. Factories were built—for example, Tenouva in 1926, which was a Jewish national cooperative that produced and distributed agricultural and dairy products; other examples include Lodzia in 1924 and Ata in 1934, which were both textile companies; SLE in 1913, Assia in 1935, and Zori in 1935, which later merged to form Teva, a pharmaceutical company. In the Arab sector, industrialization took place in the (distributed) soap industry that flourished in Nablus as well as in the tobacco industry, although both industries applied traditional manufacturing methods. Most of the Arab production remained unindustrialized, such as for fruit, vegetable, egg, meat, and milk products (Biger Reference Biger1982, Reference Biger1983). Importantly, some segments of the Jewish economy remained traditional, and some segments of the Arab economy were modernized.

Second, there is an ongoing debate among historians of Mandate Palestine about the structure of its economy: was its economy better understood as a single economy, composed of different segments, or as two separate economies—Jewish and Arab—each developing independently. Macroeconomic figures tend to support the separation thesis; in contrast, sociohistorical studies point to the many and complex interrelationships between the two economic segments, especially in the area of labor and the trade of goods (J. Metzer Reference Metzer1998; for a critique of the “dual society” model and an argument about the complex interrelationship between the Jewish and Arab societies, see Lockman Reference Lockman1996). Some intense consumer relationships ensued between Jews and non-Jews, but mostly in the traditional segments of the economy, such as in open markets where trademarks mattered less (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2014, 64). Michael Beenstock, Jacob Metzer, and Sanny Ziv (Reference Beenstock, Metzer and Ziv1993, 3–4) summarize the debate, stating that “[t]he Jewish and Arab economies in Palestine went about their separate but interrelated economic lives within a unified institutional framework which the mandatory authorities provided and administered.” The trademark system is such an institutional framework.

The debate about the economy is further complicated when viewed along the political layers: the Zionist perspective portrays the Jewish economy as a modern and capitalist one and the Palestinian as a traditional one, whereas the Palestinian perspective emphasizes the preferential status that the Jewish economy enjoyed and the condition of settler colonialism with which the Arab society and economy struggled (Seikaly Reference Seikaly2016). The two segments grew further apart in the mid-1930s during the Arab Revolt, which forced each sector to secure its own sources of products. During that time, the Arabs were on a general strike; they stopped selling their products in the Jewish market (Michaelis Reference Michaelis1938b, 21) and encouraged local, Palestinian consumption (Seikaly Reference Seikaly2016, 37). The Jewish sector saw this as an opportunity to increase self-sufficiency (Michaelis Reference Michaelis1938b, 20). Indeed, the effort to disconnect from the Arab market became a Zionist goal. Under the slogan Totseret Ha’aretz, which literally means “the country’s product” but is unequivocally understood to refer to Jewish products, Zionism promoted Jewish-only consumption.

Third, the import-export balance mattered. During the first years of British rule, the economy relied heavily on imported goods. In many markets, there was simply no local industry, such as medicine or professional tools; there was some trade with neighboring countries, especially with Syria and Egypt;Footnote 3 and there was only a little export activity, mostly of soap and edible oil. Over time, Europe became a larger source of goods, especially Britain, accompanied by extensive import from countries from which Jews had emigrated, such as Germany. The Second World War reshuffled the cards. Imports from Germany, Italy, and occupied countries ceased completely, and imports from other countries dropped dramatically. Local industries stepped in to fill the gaps. Moreover, an urgent demand arose to provide supplies to the British army, such as clothing and food. Consequently, the direction of trade reversed itself: exports increased. The trademark implications of these economic developments are important. Products—and their trademarks—circulated in all directions: foreign trademarks entered the local market; local trademarks were aimed at both local market(s) and foreign markets. Thus, the trademarks had different audiences and functions.

BRITISH INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY POLICY

Introducing intellectual property (IP) law—namely, patents, copyright, and trademarks—in Palestine was on the British checklist: it fit their international and imperial IP agendas, it reflected their mandatory mission, and it fit their Palestinian agenda. Trademark law was international from its beginning in the nineteenth century, led by France (Duguid Reference Duguid2009, 4) and extended on a global scale by the British Empire. By the 1920s, trademark law had spread globally, whether extended by the European countries to their colonies and protectorates or developed in a more organic way. A 1922 collection of trademark laws spanned over one thousand pages and contained laws from over 120 territories (Ruege and Graham Reference Ruege and Graham1922).

Britain had an international IP agenda: it realized the importance of global coordination in this field and was an active participant in various IP internationalization projects. However, not all IP fields were treated alike (Bently Reference Bently2011, 162). Copyright marked the most intense efforts at internationalization, with the Imperial Copyright Act (1911) implemented in close to its original form in most colonies. As for trademark, there was no parallel imperial legislation. This means that the local trademark legislation was not a direct reflection of British law, allowing for greater local leeway in the legislative process.Footnote 4 However, colonial laws adhered to the 1883 Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. IP fit the League of Nations’ mandate to Britain to establish a national home for the Jewish people. A viable economy was part of this plan, and trademark was one component in the legal-commercial toolbox. The mandate explicitly required the British to adhere to international conventions on behalf of Palestine, including industrial property.Footnote 5

By 1920, the British Empire had extensive experience with reforming legal systems in the colonies. The British legislative agenda for Palestine comprised several elements. The overall ideology was that of the rule of law (for critique, see Kirkby and Coleborne Reference Kirkby, Coleborne, Kirkby and Coleborne2001, 2). The British repealed much of the Ottoman law, especially laws that were inspired by French law (Friedmann Reference Friedmann1975, 328; Eisenman Reference Eisenman1977, 36). Notions of modernity and the British self-conception as missionaries of civilization added to their motivation to enact their own laws (see, for example, the account of the first governor General of Nigeria in Lugard Reference Lugard1965, 617–18). Indeed, these reforms were to serve British interests. The first to apply trademark law in the region to become Palestine were the Ottomans in 1871 and 1888 (Özsunay Reference Özsunay1995, 1544). Ottoman legislation applied throughout their empire; however, the Ottoman trademark archives have yet to be studied. In September 1919, the British military administration (the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration South), issued a notice allowing owners of trademarks registered under the Ottoman law to provisionally reregister their trademark with the British administration (Official Gazette 1919). The reconstructed trademark registry indicates forty-five such marks, which were not republished. Most of these marks belonged to English companies, such as the Gramophone Company or the British-American Tobacco Company.

Upon establishing the civil administration in 1920, the British government in Jerusalem enthusiastically began legislating (Bentwich Reference Bentwich1941; Harris and Crystal Reference Harris and Crystal2009). Some of the laws were imperial—for example, the Imperial Copyright Act (1911). Other cases were complex, such as tax law (Likhovski Reference Likhovski2018). The personal interest of the powerful British-appointed attorney general of Mandate Palestine, Norman Bentwich, was crucial in advancing the legislative project. He was a Jewish, Zionist British civil servant, the son of a well-known English lawyer, whose specialty was none other than IP. Bentwich had a special interest in enacting modern commercial laws (Likhovski Reference Likhovski2006, 57). He also authored the first Copyright Ordinance (1920) in Palestine (Birnhack Reference Birnhack2012, 96–99).

As for trademark law, in December 1921, the High Commissioner prepared a bill of the Trade Marks Ordinance 1921 and consulted the Advisory Council. The Advisory Council was an informal forum, composed of unelected representatives of all of the local communities (Likhovski Reference Likhovski2006, 24–25). The High Commissioner explained that “the necessity for fresh legislation was clear,” that Ottoman law “was not in accordance with more recent European legislation,” and that “it did not comply with the requirements of the International Convention” (Advisory Council 1921). There was some discussion in the Advisory Council that revealed that Bentwich was the ordinance’s author. The ordinance was based on the English Trademarks Act 1905, though not identical to it. The Trade Marks Ordinance 1921 (section 1) defined a trademark as “a mark used upon or in connection with goods for the purpose of indicating that they are the goods of the proprietor of such trade mark by virtue of manufacture, selection, certification, dealing with or offering for sale.” It established the position of the register of trademarks, enabling the application of trademarks on goods, excluding certain kinds of marks, such as the insignia of the mandate or foreign states, or marks that were injurious to the public. The original term was of twenty years (section 14), which was extendable for additional periods of twenty years (section 15). Infringing the right was both a civil tort and a criminal offense. The ordinance came into force on January 1, 1922.

Trademark regulations soon followed, addressing procedures, fees, and the classification system that reflected the different kinds of products (fifty classes) as well as occasional official rules (Trade Marks Rules 1922). In 1929, the Merchandise Marks Ordinance 1929 was enacted, addressing the growing problem of forged products. It criminalized the forging of a trademark, falsely and deceitfully applying a trademark to goods, and applying a false trade description. The Trade Marks Ordinance 1921 was amended several times during the mandate and was replaced in 1938. The local legislative developments resembled the British ones, albeit the source and its local version occasionally diverged. For example, the British act enabled “[d]efensive registration of well-known trademarks,” reflecting the 1925 Amendment to the Paris Convention (Trade Marks Act 1938), whereas the mandate legislation did not refer to this issue, leaving it to the courts. The Trade Marks Ordinance 1938 consolidated the Trade Marks Ordinance 1921 and its subsequent amendments, repeating most of it but amending a few rules, such as shortening the trademark duration from twenty to seven years (Trade Marks Ordinance 1938; Trade Marks Ordinance Objects and Reasons 1937) and consolidating the fifty classes into thirty-four (Trade Marks Rules 1940, Fourth Schedule). Shortly following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the mandate government enacted a special ordinance, empowering the registrar to suspend enemy trademarks.

Trademark litigation followed. Research yielded thirty-four cases during the mandate, mostly in the Supreme Court, which was the court of appeal for the registrar’s decisions.Footnote 6 In most of these cases, a foreign party was involved. Suits among local residents and companies appeared only later. In the meantime, a local trademark field developed, with the emergence of a new profession: trademark agents, with almost all agents being Jewish.Footnote 7 They handled the registration on behalf of the traders.

TRADEMARK DATA

As noted, the original trademark registry did not survive and, hence, was reconstructed for the current study. Research assistants manually reviewed the entire corpus of the Official Gazette and the Palestine Gazette, searching for notices about trademark applications. From each notice, we extracted as much data as possible. Nonetheless, we were presented with some challenges. First, trademarks were registered per class, with the law initially offering fifty different classes (that is, “chemical substances,” “tobacco”). From 1922 to 1924, applications were numbered per class—that is, Application 1 for Class 1, Application 1 for Class 2. In 1924, the numbering system changed to a general, consecutive numbering, irrespective of the class, and, in 1928, the Trademark Office renumbered 592 registered trademarks. Tidying up the data to assure that there were no missing applications nor duplications required a careful review, tracing notices and comparing applications. Second, over the years, many applications were discontinued for various reasons: either the fees were not paid, the applicant abandoned the application, or, in 1939, then-pending German applications were suspended. The trademark registrar reassigned the numbers of the discontinued applications to new ones. Again, this required close attention. Third, as noted, the Trade Marks Ordinance 1938 consolidated the fifty classes to thirty-four classes. To address this change, I created thirteen new categories so as to achieve a common denominator.

The trademark data enable searching for trends according to various variables, the most important ones being the year (when the application was submitted), the applicants’ identity (according to their address that was recorded in the application), and the trademark class. The data allow, for example, noting the number of applications for soap products over the years, seeing the trends among American applicants in all classes or in a specific industry and comparing them with German applications, and much more. A full analysis of the trademark data will be conducted elsewhere; here, I indicate only the overall figures and the distribution of applications among the local population groups.

Forty-five trademarks registered during the British military administration were reregistered under the new system. During the mandate, 9,268 applications were submitted, of which 2,005 applications were discontinued and were not published; thus, 7,263 trademarks were granted and registered. Reviewing the raw application data over time indicates that the trademark activity closely reflects the country’s macroeconomic and geopolitical events (see Figure 1).Footnote 8 Trademark applications during the initial years of Mandate Palestine were slow, with an average of 197 applications for each of the first twelve years (1922–33). This period covers the third wave of Jewish immigration (1919–23), with about thirty-five thousand immigrants, many of whom became involved in agriculture. Their products were sold in markets with no attached trademark. This period also covers the fourth immigration wave (1924–31), with almost seventy thousand immigrants, mostly from eastern European countries, and smaller groups from Yemen and Iraq. Many of them were middle class and supported themselves with small commercial businesses.

FIGURE 1. Trademark Applications in Mandatory Palestine 1922-1947

During the 1930s, we see a substantial increase (484 applications in 1934; 695 in 1935). The peak of 1935 is a consequence of both a continued general economic improvement and a notice circulated by Customs, announcing that it would toughen the enforcement of the Merchandise Marks Ordinance 1929, especially when the authentic marks were registered in Palestine (Cohn Reference Cohn1936, 163).Footnote 9 This rise coincided with the fifth wave of immigration, with 180,000 immigrants, about a third of whom were German Jews. We then see a sharp decline in 1936 to an average of 358 in the years between 1936 and 1939. This reflects the period of the Arab Revolt (1936–39). The first years of the Second World War are also notable, with a decline in the number of applications as well as a high number of discontinued applications, which rose up to 42 percent of the applications submitted in 1941. The number of applications declined to a low of 173 in 1940 (the lowest during the mandate) and 228 applications in 1941. Once the local market adjusted and began supplying the needs of the British army (Gross and Metzer Reference Gross, Metzer, Mills and Rockoff1993, 59, 63–68), there was a gradual increase, with 275 applications in 1943, 497 in 1944, and 610 in 1945. At the conclusion of the Second World War, we see a sharp increase, with 1,060 applications in 1946, the highest during the mandate. The figures for 1947 are to be viewed in the context of the civil war that broke out, finally leading to the end of the mandate, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the 1948 war.

The most extensive users of the trademark system were British traders, as shown in Figure 2. The local community accounted for about a fifth of the applications. Regional traders in the Middle East hardly used the British trademark system. This is not to say that there was no regional trade, only that such trade made little use of the British trademark system in Palestine.

FIGURE 2. Trademark Applicants by Country of Origin, Mandatory Palestine 1922-1947

The figures support the argument concerning British motivation in enacting trademark law: the British were by far the heaviest users of the local system, a finding not unique to Palestine (see, for example, Australia in Scardamaglia Reference Scardamaglia2015, 83). Within Palestine, the data clearly reflect the local national division. Local trademarks, those providing a Palestinian address, numbered 1,590. I reviewed these to determine the identity of the applicant, based on several criteria: names of individuals afford a strong indication of the applicant’s being Jewish (for example, Moshe Hanoch)Footnote 10 or Arab (for example, Abdul-Rahim Nabulsi).Footnote 11 When the name was inconclusive, the address served as an indicator—for instance, Rehovot was a Jewish townFootnote 12 and Nablus was an Arab town.Footnote 13 In cases of further doubt, I examined the mark itself. Still, in some cases, notably with corporate applicants located in mixed cities such as Jerusalem or Haifa, deciphering the identity presented a greater challenge. In such cases, I turned to external searches of the companies. The results are 1,186 “Jewish marks” (16.3 percent of the entire corpus), 261 “Arab marks” (3.6 percent), and 143 (2 percent) remained unclassified. The 1,186 Jewish marks were split as follows: 387 for food products, 272 pharmaceuticals, 230 home supplies, 98 industry, 94 clothing, 45 tobacco, 39 oil products, 17 professional tools, and 4 for transportation. The Arab marks were split unevenly. Of the 261 trademarks, 117 were for tobacco products, which was by far the largest class; 78 for home supplies, 27 for food products, 26 for oil products, 5 in industry, and 4 each in clothing and medicine.

Figure 3 shows the number of local trademark applications over the years. In 1922, the Arab tobacco traders were quick to register their marks. The numbers in both sectors were rather small during most of the 1920s, but, as of 1928, we see a departure from the trend, with the Jewish traders embracing the British trademark system, unlike the Arab traders. An exceptional period was during the Arab Revolt of 1936–39. The number of Arab applications rose during this period, but note that the numbers remained small: from seven applications in 1936 to twenty-five in 1938. The decline continued in 1939, with five applications and, in 1940, with only two applications. In the Jewish sector, 1938 saw a decline of 33 percent, from seventy-six applications in 1937 to fifty-two in 1938. However, the Jewish-owned trademark scene recovered faster in subsequent years.

FIGURE 3. Jewish and Arab Applicants, Mandatory Palestine 1922-1947

Recall that registering a trademark was not compulsory: a trademark was not a license. Traders may have used unregistered marks. The data, however, do clearly show that the Jewish traders embraced the British legal tool, whereas the Arab-Palestinian traders did not. Figure 3 supports the thesis asserting that Mandate Palestine accommodated two, mostly separate, economies. The number of trademark applications is presented here in absolute numbers. The relative sizes of the populations would have indicated a much larger gap. For example, in 1931, there were 175,000 Jews in Palestine, and twenty-eight Jewish-owned trademarks, yielding a rate of one for every 6,250 people; the larger Arab population, at 849,000, owned five trademarks, yielding a rate of one for every 169,800 people.

NATIONAL SIGNS AND SIGNIFIERS

Trademarks communicate more than information about origin. They carry additional layers of meaning. Amanda Scardamaglia (Reference Scardamaglia2015, 93) has noted that trademarks reveal “much about the prevailing legal, social, cultural, economic, and political climate of the time.” To these attributes, I suggest that trademarks convey messages about national ideologies. A trademark’s meaning is created in the interactive space between the producer, who owns the mark; the state, which authorizes its use; other trademarks, which add an intertextual layer; and consumers. This process transpires within a particular social, cultural, political, and economic fabric. This part of the article offers one way of deciphering this web in the case of Mandate Palestine. I begin with the role of trademarks in everyday life in Mandate Palestine and then turn to a semiotic analysis, focusing on Jewish and Arab graphic marks.

Trademarks in Everyday Life

Trademarks are present in shops and signs and are visible on billboards and in newspapers; today, they are present in all media. Some products, such as food and clothing, are affixed with trademarks and enter the home. What was the trademark imagery in Mandate Palestine? Mandate-period pedestrians saw far fewer commercial images than we have today and, in some cases, hardly any. Jews living in Tel Aviv were probably exposed to such signs more than anyone else. Pedestrians could see signs in Hebrew and a variety of foreign languages, marking foreign goods. About half of the trademarks bore textual elements. Jewish immigrants from Europe encountered quite a few names or symbols with which they were familiar from their previous homes.Footnote 14 Shopping was accomplished in various ways and in many locations. In open markets and when buying from peddlers, trademarks were irrelevant. Buyers could feel the goods, and they personally knew the merchant, who vouched for the quality of the goods. In grocery stores, the grocer served the clients rather than buyers removing products from the shelves (Tene Reference Tene2013, 159). Many products, such as vegetables, rice, or sugar, were sold in bulk without bearing any marks (see Figure 4).Footnote 15 Products that did bear trademarks were cigarettes, canned food, and bottled content, including wine, juice, and detergents (Tene Reference Tene2013, 159). Over time, shopping practices changed. In Tel Aviv, a few department stores opened up in the 1930s, following European trends (Helman Reference Helman2007, 106). The immediate, unmediated association between producer and product waned, and the trademark filled the gap.

FIGURE 4. Grocery in Kiryat Bialik, 1945. Photo: Jacob Rosner, Jewish National Fund (Keren Kayemet Le’Israel) Archive #013764

Most of the Arab population lived in villages, though the mandate years saw an increase in Arab urbanization (Ayalon Reference Ayalon2004, 8). In 1922, 27.5 percent of the Arab population lived in cities, rising to 36 percent in 1946. Residents and visitors in Arab towns could see some signs, mostly graphic. The villager encountered fewer shop signs and packed food products than the Arab urban resident. Regarding textual signs (not necessarily trademarks), Ami Ayalon (Reference Ayalon2004, 69–70) has noted that, “[i]n earlier times, fewer such signs were needed, and in smaller and more intimate places, their appearances has remained sparser.” Imported or mass-produced goods such as cigarettes did bear trademarks, and, later on in the mandate, shops started using signs, following Jewish practices. In many cases, the signs comprised the shop owner’s name (74). Newspaper readers could see trademarks in advertisements; many ads included the sign or the name of the product. Some trademark owners intentionally used the legal term “Trade Mark” in advertising, signaling the emergence of brands; some trademarks acquired value in themselves, independent of the product. For example, a Tel Aviv shop owner published an advertisement in the Palestine Post about “attractive bags,” adding: “Watch for the Trade Mark” (Palestine Post 1933). A Hungarian manufacturer warned customers to beware of imitations, drawing attention to the trademark, adding: “Therefore, always look for this brand and Trade-mark!” (Palestine Post 1935).

Newspaper editors also noticed the marks. In the 1930s, the Palestine Bulletin (later the Palestine Post) routinely reported the number of applications and their national division. The editors occasionally realized the cultural value of the marks and provided commentary. A report in 1931, observed, regarding the trademark shown in Figure 5, that “[t]he General Motors Near East mark contains quite a good idea. In the foreground is a motor truck. Behind, are two oxen ploughing, and in the background, the God Ra himself” (Palestine Bulletin 1931). A less favorable comment was offered regarding a mark for a weaving string by a Jewish manufacturer (Figure 6), stating: “One highly amusing mark represents Samson killing the lion. The picture is so crude that it looks as if the lion were having a good laugh at Samson. And well he might. For if the lion looks half starved, the hero looks more like a ballet dancer than a Hercules” (Palestine Bulletin 1932). Thus, trademarks were increasingly part of the regular imagery to which the local population were exposed. The trademarks blended in with their lives. However, the exposure among Jews and Arabs, city dwellers and villagers, and men and women was not equal.

FIGURE 5. General Motors, PTM#1965 (1931)

FIGURE 6. Hayman Pearlin, PTM#2240 (1932)

Reading Trademarks

Trademarks tell a story. We can now turn to the trademarks themselves. A caveat warrants our attention. We have the trademark (the signifier), but the signified messages might be lost upon us today or, worse, we might be imposing contemporary ideologies and misunderstand the original signified messages. Accordingly, the goal is to read and evaluate the marks in the context of their time and place, seeking to understand the messages conveyed to the intended audience in their original form. The discussion in the previous subpart, along with scholarly studies concerning everyday life during the mandate, provides such context. The focus here is on the national features of trademarks. This focus led us to examine the 1,590 local trademarks (75 percent of which were Jewish marks; 16 percent Arab marks, and 9 percent unidentified). Narrowing the dataset to graphical marks resulted in 881 marks: 653 of which were Jewish-owned marks (55 percent of the Jewish-owned trademarks), and 228 were Arab-owned marks (88 percent of the Arab-owned marks). In other words, Arab-owned marks used more graphics and less text, compared to Jewish-owned marks. A possible explanation for this difference is the lower literacy rates among Arabs, especially Muslims.Footnote 16 The signs were published in the Official Gazette in black and white. The 881 marks were reviewed and coded as to their content, according to several categories: religious symbols, local images (for example, the use of camels or human figures in traditional attire), local landscapes, fauna and agriculture, oceanic imagery, animals, and other images that were relatively prevalent, such as a crown.

Arab-owned Trademarks

The graphic Arab-owned trademarks could be found mostly in several classes of goods: tobacco, soap, edible oil, and citrus fruit.Footnote 17 Of the Arab-owned pictorial trademarks that incorporated text, the languages used were Arabic, a foreign language, or both, but never Hebrew. This finding is reflective of the separate markets: Arabs did not market their trademark-bearing goods to the Jewish population; if they did so, they did not include Hebrew texts. Both Arab-owned and Jewish-owned marks for citrus fruit were largely intended for export and, accordingly, used foreign languages (Figures 7–11).Footnote 18 They used the famous indication of JAFFA ORANGES. The legal concept of geographical indication had yet to be introduced. In fact, the Trade Marks Ordinance 1921 explicitly excluded trademark protection for “words whose ordinary signification is geographical” (section 5(5)), as did the Trade Marks Ordinance 1938 (section 8(f)).Footnote 19 Thus, no one owned this term, making it free for all to use.Footnote 20 Some of the Arab-owned marks included images that today we would call orientalist, such as a sheik (Figure 8), a biblical image—though with a twist, as the spies carry oranges rather than grapes (Figure 9)—and a Turkish pasha (Figure 10). In other cases, the images used were European, such as one depicting a Western-dressed woman, having the title PRINCESS, with adjacent oranges (Figure 11).

FIGURE 7. Hassan Eff. Essawi, PTM#2249 (1931)

FIGURE 8. Arthur Roch, PTM#2270 (1932)

FIGURE 9. Georges Abouphele, PTM#3896 (1936)

FIGURE 10. Sayed Hajaj, PTM#4844 (1938)

FIGURE 11. Ibrahim Younes, PTM#4074 (1936)

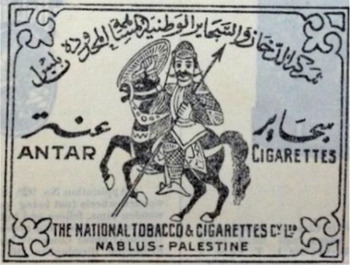

The use of Middle Eastern images was ubiquitous, such as the image of a camel used in connection with tobacco or soap. Camels were featured in Jewish, Arab, and foreign marks (see, for example, for soap in Figure 12). Armed cavaliers, typically holding a spear, first appeared in 1926 and then again in subsequent years (Figure 13).Footnote 21 Recall the pasha used for exporting oranges (see Figure 10). Only a few figures sported attire that did not immediately indicate an Arab identity, such as a trademark for agricultural substance (Figure 14). In only one case, the trademark used a familiar Western image, that of the Statue of Liberty, for soap (Figure 15).

FIGURE 12. Ahmad Hassan El-Shaka’a Ltd., PTM#6663 (1945)

FIGURE 13. National Tobacco & Cigarettes Company Limited, PTM#952 (1926)

FIGURE 14. Hanna A. Kattan, PTM#6323 (1943)

FIGURE 15. Mohd. Arif Bin Misbah Al-Nablus, PTM#6523 (1944)

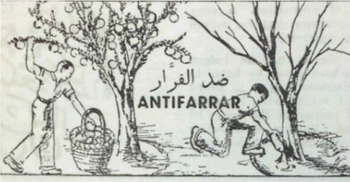

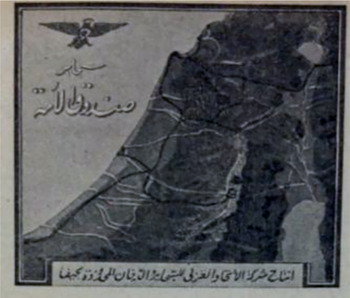

Trademarks bearing unequivocal national elements were rare. Some of the Arab-owned trademark owners incorporated the term “national” in their name, and, hence, it featured on the marks. One mark registered in 1944 included a map of Palestine. Borders comprised a heated political issue during the mandate, with a pan-Arab vision that had spread in the early 1930s; hence, it is interesting to note that, pan-Arabism notwithstanding, the map depicted only Palestine, excluding Syria, Lebanon, or trans-Jordan (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16. Arab Union Cigarette & Tobacco Co. Ltd., PTM#6893 (1945)

Thus, whereas the language used (mostly Arabic) and the one not used (Hebrew) in Arab-owned trademarks indicate separation along the lines of nationality, there were relatively few other images that could be deemed national in tone. The symbols used for the local market were mostly familiar to the consumers and had familiar cultural meanings: camels, cavaliers, crescents, or the occasional use of a mosque. National images were few and relatively subtle. The symbols used for export sought to appeal to the imagination of foreign consumers. Regarding the latter, the result was a self-enhancing spiral: the local traders used local images for exported goods, envisioning how European consumers imagined the locals, perhaps trying to attribute an exotic flavor to the product. Clearly, they used what they thought would best promote sales.

Jewish-owned Trademarks

Examining the above parameters of language, images, and national symbols in the Jewish-owned marks reveals a different picture. Various national symbols featured more prominently in Jewish-owned marks than in Arab-owned marks. As for language, the first signs submitted by Jews were not published, but the registry’s entries indicate they were in Hebrew.Footnote 22 Most Jewish marks used Hebrew, English, or both, and some also used Arabic, indicating that some of the Jewish products were aimed for all markets in Palestine and perhaps for markets in neighboring countries—for example, a Jewish-owned trademark for tobacco, a market dominated by Arab traders (Figure 17).Footnote 23 However, the dominant language was Hebrew. The choice was deliberate and should be of no surprise to those familiar with the Yishuv, the Zionist-Hebrew community in Mandate Palestine (Even-Zohar Reference Even-Zohar1980, 171–72; Shavit Reference Shavit and Shavit1989, 23). Hebrew carried with it a strong national message. The preference for Hebrew over Yiddish and European languages drew a distinct line between the diaspora and the national home, between the old and the new society, and between the Old Jew and the New Jew (Shapira Reference Shapira1997, 168, 185, 194–96).

FIGURE 17. Shalom Siri, PTM#2293 (1932)

As with Arab-owned trademarks, citrus-related trademarks often used only a foreign language, according to the targeted foreign market.Footnote 24 Only few of the citrus trademarks appeared in Hebrew, reflecting the much smaller local market.Footnote 25 The imagery used in the Jewish-owned trademarks for exported citrus fruit was often of a Middle Eastern character, as was the case with Arab-owned marks. Various marks featured camels (Figure 18) and peasants (fellah);Footnote 26 a 1928 mark featured a woman in traditional dress (though not distinctly Arab or Jewish), bearing a box of oranges on her head, a traditional way of carrying goods in the Middle East (Figure 19).

FIGURE 18. Nahum Perlman, PTM#1991 (1931)

FIGURE 19. Zwi (Henry) Izakson, PTM#1423 (1928)

Local images are found in other trademarks, which were not necessarily for exported products. For instance, camel images were used for cotton products; in 1922, one of the first Jewish-owned trademarks—this one for tobacco—featured a person dressed in an Arab gown and kafiyah (a traditional headdress), riding a camel;Footnote 27 in 1930, a mark featured an Arab figure leading a camel loaded with a large jar of honey (Figure 20). An Arab khan (inn in Arabic) also appeared in Jewish-owned trademarks.Footnote 28 These images appeared mostly up until the early 1930s. Thereafter, fewer Middle Eastern-inspired images appeared, with the romantic view of the land giving way to Zionist marks. The national, Zionist language of the trademarks is evident in biblical images, the use of landscapes of Eretz Israel, using Hebrew names for local agricultural products (namely, citrus fruit); other images included national signs, such as a flag, the Star of David, and references to the national anthem, and, finally, the image of the Halutz (pioneer in Hebrew).

FIGURE 20. Robert Blum, PTM#1841 (1930)

Biblical images

The emerging wine industry, a significant symbol of the Zionist project, which found its roots in the late nineteenth century, used the image of the twelve spies sent by Moses to survey the land of Canaan. According to the biblical story, the spies returned after forty days, with two of them bearing a large cluster of grapes hung on a pole.Footnote 29 This image has been used in numerous wine products (see, for example, Figure 21).Footnote 30 Another biblical reference is a quote from the Book of Ezekiel, indicating God’s promise to the elders of Israel that the land will be the most glorious of all.Footnote 31 Yet another religious image was a cruise of oil, an allusion to the Hanukkah miracle.Footnote 32 The Star of David (though not a biblical symbol) also appears in several signs.Footnote 33

FIGURE 21. Cooperative Society of the Winegrowers of the Cellars of Rishon-le-Tsiyon and Zichron Yaaqov, Limited, PTM#274 (1924)

Landscapes of Eretz Israel, the Hebrew name of Palestine

The land played a crucial role in Zionist ideology. Infused with biblical ideas about the land of milk and honey, Zionists set out to settle and cultivate the land. Familiarizing the land to the Jewish population was an important mission. The landscapes we find in trademarks are mostly generic rather than featuring a particular area. Consider a 1925 trademark for wine. It is a picture rich in detail, appearing more like a painting than a mark (Figure 22). It comprises a mountain and the sea, the Star of David, palm trees, camels, fields, and a dove. The message is typical: the land is peaceful, vast, and rich, awaiting cultivation. A trademark for candles from 1940 was Namal (Hebrew for port), depicting the newly opened Tel Aviv port, celebrated as a major achievement of the local Jewish community (Stern Reference Stern1982) (Figure 23).

FIGURE 22. S. Friedman and Sons, Carmel Original, PTM#643 (1925)

FIGURE 23. Eliahu Perez Pasternak, PTM#5641 (1941)

Hebrew names

Again, the citrus-related trademarks provide a rich semiotic site since oranges were meant mostly for export. Unlike the parallel Arab-owned marks, many of the names of the Jewish brands were in Hebrew, such as Ophir,Footnote 34 Pardes,Footnote 35 or Ada.Footnote 36 As noted, the citrus trademarks included local, Middle Eastern imagery. However, the images were appropriated and rebranded by using Hebrew names alongside the local images that referenced the biblical messages regarding the fertility of the land of honey and milk, entangling it with Zionist, Hebrew content.

National images

Zionist messages were evident in the use of various national images. For example, a flag, though in some cases not yet bearing the Star of David, appeared on a 1938 trademark for cigarettes, called Degel (Hebrew for flag) (Figure 24), and the word Ha’tikva (Hebrew for hope), which is the title of the national anthem, was also used for cigarettes (Figure 25). Tenouva, the Jewish agricultural cooperative, used an image of a Halutz plowing the field, with a typical landscape in the background, alongside a map of Palestine (Figure 26). Together, these images conveyed a message: a state was in the making. It had a territory, a flag, and an anthem.

FIGURE 24. C. Bejarano Bros., PTM#5096 (1938)

FIGURE 25. Union Tobacco and Cigarette Company, Ltd., PTM#2119 (1931)

FIGURE 26. Central Marketing Institution of “Tenouva” agricultural Co-operative Societies for Palestine, Limited, PTM#2428 (1933)

Jewish-owned trademarks began referring to the place of production. The term “Made in Palestine” was used by some of the Arab traders. The Jewish traders used a different term— Totseret Ha’aretz, referring to Jewish-made products. This notice served the Zionist ideology (Helman Reference Helman2007, 123; O. Metzer Reference Metzer2012, 315–20). The term was in general use among the Hebrew community in Palestine as of the 1920s, reaching its peak in the second half of the 1930s during the Arab Revolt.Footnote 37 The first use of the term was in a trademark in 1932 for citrus fruit,Footnote 38 and, thereafter, we find it used for house supplies, such as towels and pots,Footnote 39 or stationery, cotton, cutlery, and brushes.Footnote 40 In 1940, following the Arab Revolt and as the Arab and Jewish markets grew apart, the National Council of Palestine Jews (Ha’va’ad Ha’leumi Le’knesseth Israel) registered it as certification marks for eggs and fruit.Footnote 41

The image of the Halutz (the plural form is Halutzim) was the most powerful Zionist image at the time. The Halutzim were the first Zionists who immigrated to Palestine, lived in the as yet undeveloped rural areas rather than in towns. The Halutzim paved roads, dried swamps, and cultivated the land. Prominent among them were the immigrants of the second and third waves of immigration (1904–14 and 1919–23, respectively), who were very different from the more bourgeoisie fourth and fifth waves. The Halutzim were the quintessential Zionists: they labored in harsh conditions, setting the tone for many years, well after the State of Israel was created, leading the Hebrew community and then the state. The image of the Halutz was one of a strong—physically and emotionally—secular individual who was down to earth in his or her daily work, yet also romantic and inspired by a powerful national vision, willing to give up convenience to contribute to the emerging national collective. In the social hierarchy of the times, the Halutz ranked first.

This image set a challenge for businesses. The Halutzim were not the typical consumers. They consumed the minimum needed, and, wherever possible, they produced their own tools, machines, and food. Their ideology was of asceticism rather than the emerging consumerist society, which was often considered hedonistic and associated with ideas of progress and capitalism (Helman Reference Helman2007, 134–36). The result was a gap between the image and the traders’ needs. Their solution was a capitalist, perhaps cynical, one: the traders coopted the image of the Halutzim. Anat Helman (Reference Helman2007, 125) has examined advertisements and concluded that the image of the heroic Halutz was relatively rare. However, in the context of trademarks, we do find the Halutz, albeit with the occasional twist. One trademark had the Halutz plowing the land alongside a map of Palestine (Figure 26). Tenouva, the trademark’s owner, was the agricultural cooperative, so the use of a Jewish farmer, dressed in Western clothes and a hat, made sense. But how could the Halutz image be coopted for cigarettes? One trader presented the Halutz as a smoker (Figure 27). The name of the brand was Ha’Poel, meaning the worker; thus, the trademarks capitalized on a socialist symbol. Whereas we can assume that some of the Halutzim were smokers, it appears to be a bit of a stretch of the conventional image. Using the image of a Halutz for strong twine appears more sensible, placing the Halutz in an orchard (Figure 28). An interesting case of cultural fusion is a mark for a chemical substance used in agriculture (Figure 29), which was owned by a foreign company, Pioneer Products. The image and original meaning of Pioneer referred to the American pioneer, moving west, exploring new frontiers. Nevertheless, it resonated perfectly with local sentiments: it was a cultural transplant.

FIGURE 27. Union Tobacco & Cigarette Company, Limited, PTM#2118 (1931)

FIGURE 28. Jerushalmi Chaim & Zalman, PTM#2406 (1933)

FIGURE 29. Hayman Pearlin, PTM#2310 (1932)

Zvi Morduchovich from Tel Aviv imported sardines. He used an image of a Halutza (female form of Halutz), reflecting the relative gender equality among the Halutzim (Figure 30). Note her stance and the fact that she is wearing work clothes, with a hoe resting on her shoulder, signaling strength and hard work, along with a gentle smile. Whereas the heading reads “Halutza E’I” (Eretz Israel), the product was foreign: Portuguese sardines. This was probably a commercial error: depicting the local Zionist taking pride in a foreign product was incongruent. A year later, Morduchovich applied for another trademark for sardines. The image was of a Halutz in a working position. There is no mention of the foreign source of the food (Figure 31). The text reads “Halutz E’I,” adding two Stars of David (with his initials, ZM, on one of them, and TA, for Tel Aviv, on the other).

FIGURE 30. Zvi Morduchovitch, PTM#4320 (1937)

FIGURE 31. Zvi Morduchovitch, PTM#4796 (1938)

Additional uses of the image of the Halutz were for dairy products.Footnote 42 A related image was that of the laborer. This image was not necessarily tied to agriculture but viewed as a source of admiration for his hard labor, in contrast to the image of the “Old Jew,” who stayed behind in Europe. The physical strength of the “New Jew” was an important Zionist feature. Engaging in sports was particularly esteemed. The first Ha’Poel games, involving Jewish athletes, took place in 1928 in Tel Aviv. By 1935, the event drew ten thousand participants. Local traders took advantage of its popularity, such as in a trademark for perfume (Figure 32).

FIGURE 32. Max Khalef, Trading as the Laboratory and Cosmetics Works “Nered”, PTM#3087 (1935)

National, Zionist images were not the only ones used on trademarks. Some signs used Greek mythology, such as Atlas, Venus, and Hercules for oranges, and Hercules, once again, for twine.Footnote 43 However, the cumulative result was there: many Jewish-owned trademarks contained national images of various kinds, whereas Arab products carried trademarks that were less available to Jewish consumers.

CONCLUSION

Trademarks are a market tool, but they also reflect the zeitgeist in a specific period and place. This article has suggested that we use trademarks to explore economic, political, and cultural aspects of a given society. Trademark data can serve as a rich resource for a sociolegal inquiry, and this article has examined trademark law in Mandate Palestine in three phases. First, applying a critical framework of legal transplants has reflected how the foreign tool of trademark law fit British interests in handling IP on international and imperial scales as well as in accommodating their interests in Mandate Palestine. The legal transplantation framework led us to examine how the colonial concept was received by the local communities.

Second, trademark data provided a surprising reflection of the economic changes and national events. The analysis of trademarks in Mandate Palestine indicates that the Jewish and Arab markets used trademarks differentially. Jewish traders embraced the British legal tool; however, Arab traders used it far less, the only exception being a relatively brief episode in the early 1920s, notably involving the tobacco market. This differential reception of the colonial trademark system requires further analysis: was it a reflection of the different structure of the Jewish and the Arab markets, the first moving faster than the latter toward industrialization? Relatedly, the different commercial patterns may also provide an explanation, with the Arab sector relying more on local sales, where interpersonal relationships render trademarks less relevant. It may also be that the Arab avoidance of the British system reflected their mistrust of the foreign, colonial government. Perhaps other barriers of entry to the trademark market were at play, such as language, costs, and access to professional agents. The answer is all of the above explanations. Either way, the current analysis partially supports the “divided economy” thesis of Mandate Palestine’s economy—namely, that the Jewish and Arab markets were separate and parallel rather than integrated. This is not to say that Arabs did not sell their products in the Jewish markets; they did, albeit in traditional-style markets, with the producer selling products directly to consumers. Moreover, the Arab traders may have used various marks for their products without having sought British legal protection.

Third, supplementing the analysis with a semiotic examination of trademarks has indicated how the foreign legal mechanism of trademark was appropriated to serve additional functions other than that of the market signal. Trademarks were used as a medium to convey cultural and national messages, coopted to serve business interests. Jewish traders used a wide variety of images and symbols, including religious, oriental, and many Zionist images. Arab traders used some local and religious images but hardly any national ones. It is quite likely that the Arab traders preferred non-British channels to convey such messages. When we zoom in on the rich trademark mosaic of Mandate Palestine, we can see its bits and pieces as they reflect the identity politics of the time.