Article contents

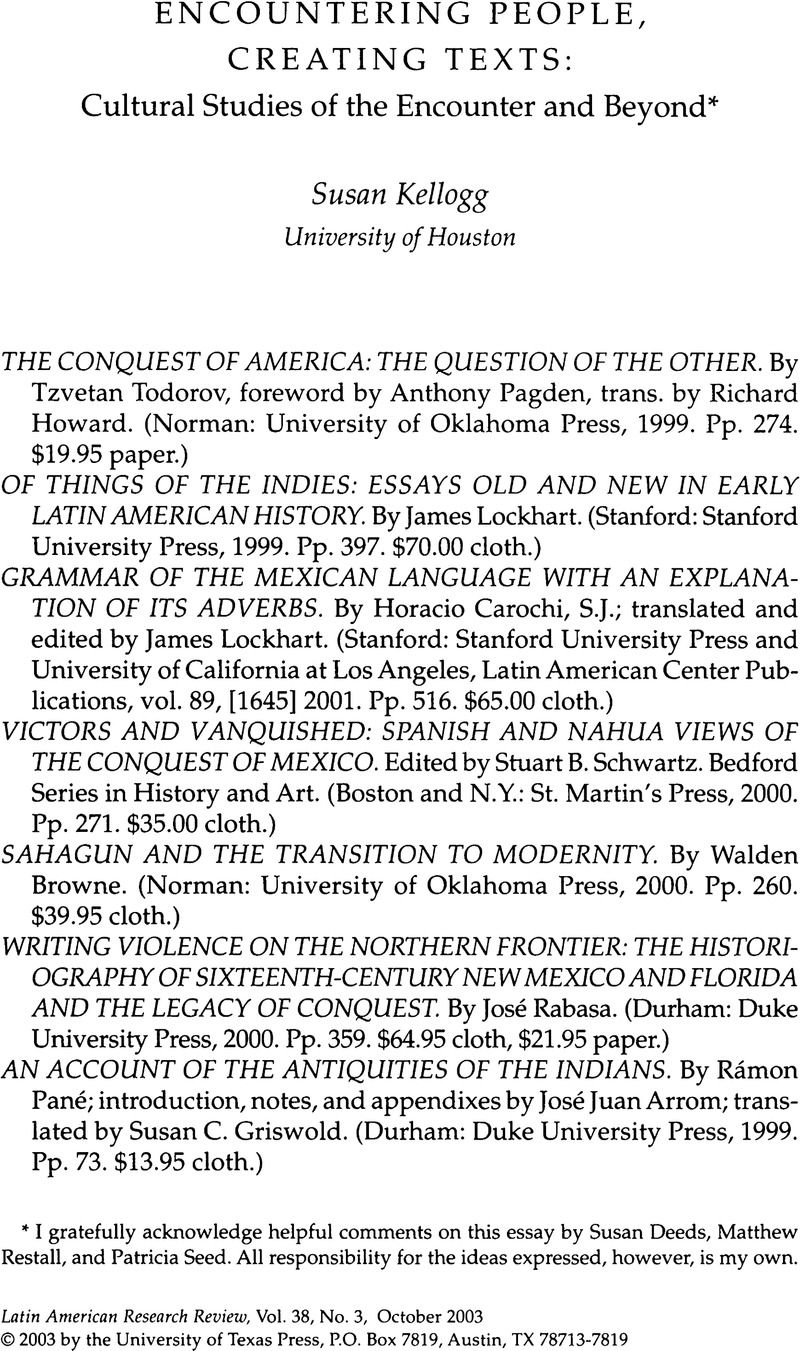

Encountering People, Creating Texts: Cultural Studies of the Encounter and Beyond

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2003 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

I gratefully acknowledge helpful comments on this essay by Susan Deeds, Matthew Restall, and Patricia Seed. All responsibility for the ideas expressed, however, is my own.

References

1. James Axtell discusses the massive English-language literature in his review essay “Columbian Encounters, 1992–1995,” William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Ser., 52, no. 4 (1995): 649–96.

2. A recent work that reemphasizes material factors as critical in explaining European expansionism is Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 1997). Also see Warwick Bray, ed., The Meeting of Two Worlds: Europe and the Americas, 1492–1650 (Oxford: The British Academy and Oxford University Press, 1993). Useful critiques of Diamond's and other similar arguments may be found in George Raudzens, ed., Technology, Disease and Colonial Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries: Essays Reappraising the Guns and Germs Theories (Leiden: Brill Press, 2001). Benjamin Keen commented on studies of the Encounter and Conquest using social history approaches in his essay, “Recent Writing on the Spanish Conquest,” Latin American Research Review 20, no. 2 (1985): 161–71. Overviews of social history approaches include Keen, “Main Currents in United States Writings on Colonial Spanish America, 1884–1984,” Hispanic American Historical Review 65, no. 4 (1985): 657–82; John Kicza, “The Social and Ethnic Historiography of Colonial Latin America: The Last Twenty Years,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 45, no. 3 (1985): 453–88; and William B. Taylor, “Between Global Process and Local Knowledge: An Inquiry into Early Latin American Social History, 1500–1900,” in Olivier Zunz, ed., Reliving the Past: The Worlds of Social History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 115–189. Susan Deans-Smith earlier engaged the transition from social to cultural analyses in works of colonial Mexican history in “Culture, Power, and Society in Colonial Mexico,” Latin American Research Review 33, no. 1 (1998): 257–77.

3. William Roseberry's essay, “Balinese Cockfights and the Seduction of Anthropology,” in his Anthropologies and Histories: Essays in Culture, History, and Political Economy (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 20–25, remains the clearest critique of Geertz's approach to culture, its products and patterns. For further discussion of the text-as-culture approach in colonial Latin American history, see Eric Van Young, “The New Cultural History Comes to Old Mexico,” Hispanic American Historical Review 79, no. 2 (1999): 224–36. Two essays I found helpful in thinking about the transition from social to cultural approaches in recent history writing are Patricia Seed's “Poststructuralism in Postcolonial History,” The Maryland Historian 24, no. 1 (1993): 9–28; and William Sewell's “Whatever Happened to the ‘Social’ in Social History?” in Schools of Thought: Twenty-Five Years of Interpretive Social Science, eds., Joan W. Scott and Debra Keates (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

4. See also La conquete de l'Amerique: la question de l'autre (Paris: Seuil, 1982) and Tzvetan Todorov's The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other, trans., Richard Howard (N.Y.: Harper and Row, 1984).

5. For overviews of the form of literary analysis known as New Historicism, see for example, H. Aram Veeser, The New Historicism (N.Y.: Routledge, 1989) and Catherine Gallagher and Stephen Greenblatt, Practicing New Historicism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2000).

6. See James Lockhart, Spanish Peru, 1532–1560: A Colonial Society (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968) and The Nahuas after the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992).

7. For an overview of much of this work, see Matthew Restall, “A History of the New Philology and the New Philology in History,” Latin American Research Review 38, no. 1 (2003): 113–134.

8. See, for example, Angel María Garibay K., Llave del náhuatl: colección de trozos clásicos, con gramática y vocabulario, para utilidad de los principiantes, rev. ed. (México: Porrua, 1961); J. Richard Andrews, Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975); Thelma D. Sullivan, Compendio de la gramática náhuatl (Mexico: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1976); and R. Joe Campbell and Frances Karttunen, Foundation Course in Nahuatl Grammar, 2 vols. (Austin: Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas, Austin, 1989).

9. James Lockhart, Nahuatl as Written: Lessons in Older Written Nahuatl, with Copious Examples and Texts (Stanford: Stanford University Press and University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Latin American Center Publications, vol. 88, 2001).

10. Miguel León Portilla, ed., The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, rev. ed., trans. from Nahuatl into Spanish by Angel María Garibay K., trans. to English by Lysander Kemp (Boston: Beacon Press, 1992).

11. For example, many of the essays in J. Jorge de Alva, H.B. Nicholson, and Eloise Quiñones Keber, eds., The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico (Albany, N.Y.: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, University at Albany, State University of New York, 1988) take this point of view.

12. Recent studies that have done much to amplify our understanding of the origins and impact of the Guadalupe phenomenon include Lisa Sousa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart, trans. and eds., The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's “Huei tlamahuiçoltica” of 1649 (Stanford and Los Angeles: Stanford University Press and UCLA Latin American Center Publications, vol.84, 1998); and David A. Brading, Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition across Five Centuries (Cambridge and N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

13. Ida Altman's earlier volume Emigrants and Society: Extremadura and America in the Sixteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989) and John Kicza's Colonial Entrepreneurs: Families and Business in Bourbon Mexico City (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983) are representative of such work, at least for Mexico. Relevant works of social history for other areas are cited in Kicza, “The Social and Ethnic Historiography” and Taylor, “Between Global Process and Local Knowledge.”

14. His analysis is in some ways reminiscent of the more sophisticated study of New Spain's Second Audiencia found in Ethelia Ruíz Medrano, Gobierno y sociedad en Nueva España: Segunda Audiencia y Antonio de Mendoza (Zamora, Michoacán: El Colegio de Michocán y Gobierno del Estado de Michoacán, 1991).

15. Relevant works include Brian Hamnett, Roots of Insurgency: Mexican Regions, 1750–1824 (N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 1986); John Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750–1940 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Peter Guardino, Peasants, Politics, and the Formation of Mexico's National State (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996); and Eric Van Young, The Other Rebellion: Popular Violence, Ideology, and the Mexican Struggle for Independence, 1810–1821 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). Also see Friedrich Katz, ed., Riot, Rebellion and Revolt: Rural Social Conflict in Mexico (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988); and Leticia Reina, ed., Las luchas populares en México en el siglo XIX (Mexico: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS), 1983).

16. See the still essential works of John Chance, Race and Class in Colonial Oaxaca (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1978); Conquest of the Sierra: Spaniards and Indians in Colonial Oaxaca (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989); and Ronald Spores, The Mixtecs in Ancient and Colonial Times (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984). Spores' earlier work on Mixtecs in the pre-Hispanic period also retains importance. See The Mixtee Kings and Their People (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967).

17. Also see Stuart B. Schwartz, “Denounced by Lévi-Strauss: CLAH Luncheon Address,” The Americas 59, no. 1 (2002): 1–8.

18. Quote from Axtell, “Columbian Encounters,” 679. Also see Sewell, “Whatever Happened to the ‘Social’,” 215–16.

- 2

- Cited by