No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

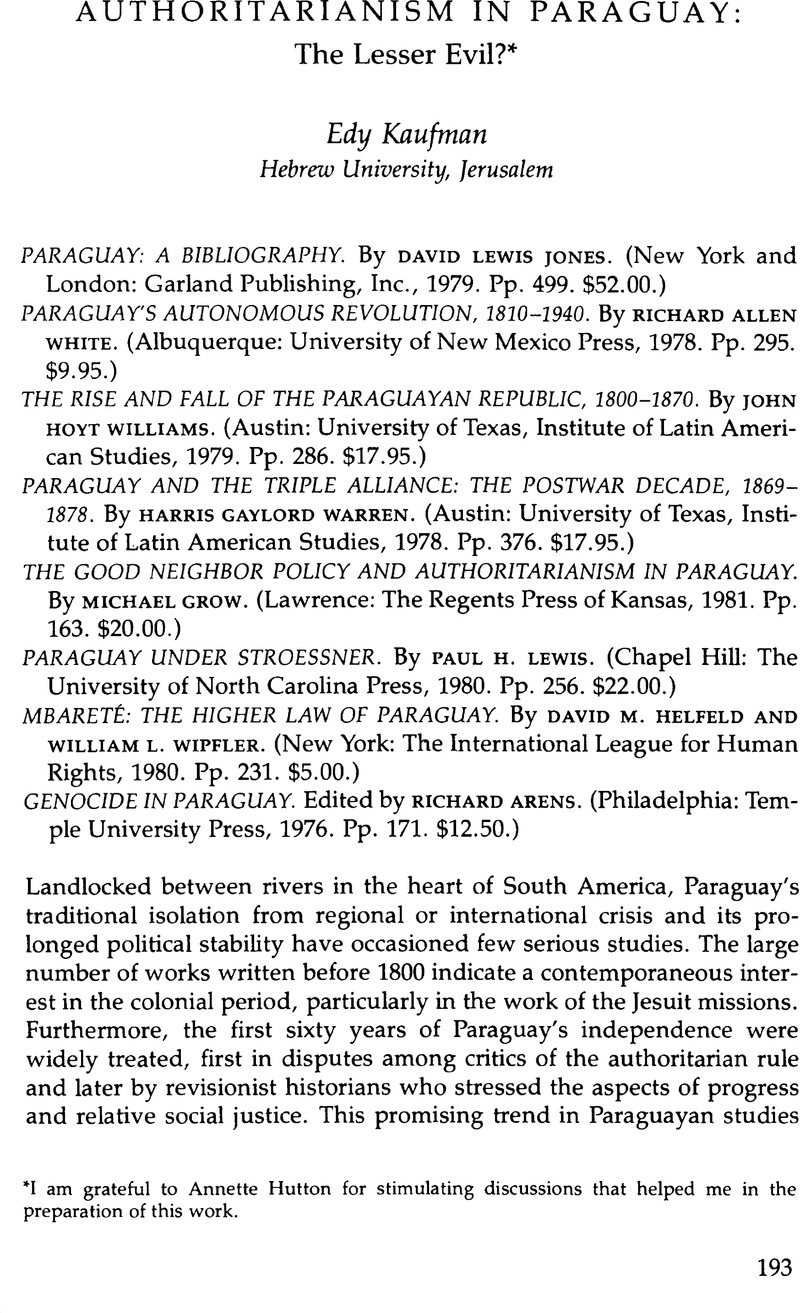

I am grateful to Annette Hutton for stimulating discussions that helped me in the preparation of this work.

1. Among the books missing from Jones's bibliography are the following: Themistocles Linhares, História Econômica do Mate (Buenos Aires: Talleres Portes, 1936; Rio de Janeiro: 1969); Prudencio de la Cruz Mendoza, El Dr. Francia en el Virreynato del Plata (Buenos Aires: Talleres Porter, 1936); Eduardo Salterain, Artigas en el Paraguay (Asunción: 1950); Francisco Wisner de Morgenstern, El Dictador del Paraguay José Gaspar de Francia (Buenos Aires: Ayacucho, 1957); Victor Arreguire, Tiranos de América: el Dictador Francia (Montevideo: 1898); Blanco Sánchez, Jesús L., El capitán de Antonio Tomás Yegros (Asunción: Instituto Paraguayo de Investigaciones Históricas, 1961); Guillermo Cabanellas, El Dictador del Paraguay, el Doctor Francia (Madrid and Buenos Aires: Editorial Claridad, 1946); Enrique Corrales y Sánchez, El Dictador Francia (Madrid: Semblanza, 1889); José Segundo Decoud, Recuerdos históricos: homenaje a los próceres de la independencia paraguaya (Asunción: 1894); Ramón Gil Navarro, Años en un calabozo o sea la desgraciada historia de veinte y tantos argentinos muertos o envejecidos en los calabozos del Paraguay (Rosario: El Ferrocarril, 1863); Tomás Guido, Los dictadores del Paraguay (Buenos Aires: 1879); Prudencio de la Cruz Mendoza, Militarismo en el Paraguay (Buenos Aires: 1916); Diego Luis Molinari, Viva Ramírez (Buenos Aires: Editorial Coni, 1938); Felix Outes, Los restos atribuidos al Dictador Francia (Buenos Aires: Casa J. Peuser, 1925); José M. Ramos Mejía, Rosas y el Doctor Francia (Madrid: Editorial América, 1917); Eduardo Aramburu, Manifiesto al pueblo paraguayo (Montevideo: 1876); and many others.

2. See for instance Helen Graillot, “Paraguay,” in Leslie F. Manigat et al., Guide to the Political Parties of South America (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1973), pp. 368–92; Paul E. Hardley, “Paraguay,” in Ben G. Burnett and Kenneth F. Johnson, eds., Political Forces in Latin America (California: Wadsworth, 1968); Pablo Neruda, “El Doctor Francia,” Obras completas, second edition (Buenos Aires: Losada, 1962); Richard Bourne, Political Leaders of Latin America (Baltimore: Penguin, 1969).

3. Jones's selected list does not include Asunción's periodicals of the last century such as El Centinela (1867-68), El Eco del Paraguay (1855-57), La Época (1857-59), and El Paraguayo Independiente (1845-52). Important contemporary newspapers and periodicals not mentioned in the bibliography include ABC Color, Sendero, Patria, El Radical, and Buenos Aires-based exile periodicals such as Febrero (Febrerista), El Ateneo (Febrerista), and Revolución (Liberal).

4. As White correctly observes: “In addition to the personalistic Latin American historical tradition, the historiography of this period is further complicated by a confusion between rhetorical form and historical content. Attempting to discredit Francia's regime and thereby support their own position, Francia's enemies have utilized the rhetorical device of attacking his character. Since historians have accepted these partisan attacks as history … even the later works attack … Francia rather than providing an objective analysis of the epoch's history” (p. 13).

5. See André Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969), p. 287, and his well known “Development of Underdevelopment,” in Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution (New York: Monthly Review, 1969), pp. 3–17.

6. White not only illustrates that in 1834 thirteen military drummers made 4.25 pesos each, but he also provides the salaries of the master drummer and the apprentice drummers (p. 260). This attention to detail also reflects White's scholarly approach in larger arenas.

7. In what could be considered a superfluous and folkloric description, Williams recorded for posterity the splendour of the time: “There were almost a hundred guests and a military brass band, and … though no woman present wore gloves, ‘they had not forgotten their rings, which all shone in greater quantity than could be contained on their fingers; the majority were shoeless.’ That evening the elite mostly danced the quadrille … the music ‘more thunderous than harmonious/ … the party … lasted until two in the morning, some men ‘grabbing handfuls of sweets and filling their girlfriends’ skirts with them' before leaving for home” (p. 109).

8. Some of Warren's comments can be regarded as sexist: “The lower class Paraguayan women, especially when young, elicited admiring comments from foreign visitors. … Their high cheekbones, square chins … hardly met a French man's standard of beauty, but he could appreciate a trim ankle and a well-rounded bosom. Unencumbered by corsets or other articles of torture, young women quickly lost their lithe figures, a fate common to women everywhere” (p. 156).

9. Samuel Bemis, The Latin American Policy of the United States (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1943).

10. See articles by Jeanne Kirkpatrick, “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” Commentary 68, no. 5 (November 1979): 34–45; and “U.S. Security and Latin America,” Commentary 71 (January 1981): 29–40.

11. O'Donnell's concept is discussed by several important scholars in David Collier, ed., The New Authoritarianism in Latin America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979).

12. Stroessner's rule is often described as a “benevolent authoritarian regime.” See, for instance, Paul Hardley's “Paraguay,” in Ben G. Burnett and Kenneth F. Johnson, eds., Political Forces in Latin America (Belmont, Cal.: Wadsworth, 1968), p. 380. He is also called a “democratic despot” (Newsweek, 12 February 1973). His supporters contend that he can rely on the “sympathy and confidence of his citizens [because] without internal dissidences and without any other ideal than the patriotic aim to place a firm and strong authority over the wide base of the popular verdict, as a foundation of constructive peace and work, it is Stroessner's policy which has permitted the positive achievement of the values of the nation.” Alfred Stroessner, His Life and Thoughts (Asunción: El Arte, 1958), p. 3.

13. The allegiance of the peasant masses is maintained by means of traditional “Dyadic Contracts” and a patronage system based on the personalistic approach characteristic of caudillo politics. This issue is discussed by Frederick Hicks in “Interpersonal Relationship and Caudillismo in Paraguay,” Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs 13, no. 1 (January 1971): 89–111; see also E. Wolf, “Caudillo Politics: A Structural Analysis,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 2 (January 1967): 168–79.

14. Helfeld and Wipfler, p. 155.

15. Amnesty International, Paraguay Briefing Paper no. 4 (London: Amnesty International, 1976); and Amnesty International, Muertes en la tortura y desapariciones de presos políticos en Paraguay (London: Amnesty International, 1977).

16. Mark Munzel, The Aché: Genocide in Paraguay, Document no. 11 (Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs [IWGIA], 1973); and Mark Munzel, The Aché: Genocide Continues in Paraguay, Document no. 17 (Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 1974).

17. See article by Paraguayan sociologist Miguel Chase Sardi, “API Denies the Declarations Emitted by Arens,” Hoy (Asunción), 22 February 1979.

18. Kim Hill (unpublished manuscript, circa 1980). Hill worked with the north tribe of Aché from October 1977 to February 1979 and March to August 1980. His meticulous and factual disagreements with Munzel and Arens's accounts seem to be extremely credible.

19. Ronald H. McDonald, “The Emerging New Politics in Paraguay,” Inter-American Economic Affairs 35, no. 1 (Summer 1981):44.