As archaeologists have begun to consider social subcultures through the theoretical lens of agency, additional group identities are coming into focus, including class, ethnicity, and gender (Meskell Reference Meskell and Hodder2001). One of the challenges of an engendered archaeology is the male bias that has too often permeated interpretation, in part as the result of an assumption that material culture is predominantly produced by and for male actors (but see Conkey and Spector Reference Conkey, Spector and Schiffer1984; Wylie Reference Wylie1992). Instead, a goal should be to identify and explore how other genders (and other nondominant groups) used objects to communicate their own symbolic messages (Hodder Reference Hodder1982).

Groups develop means of coded communication, verbal as well as visual, that are used to transmit in-group messages while excluding nongroup members. Language is an obvious example: the use of jargon, slang, or prestige languages constructs identity and also limits participation in these discourses to group members. In prehispanic Mesoamerica, for example, the Zuyuan dialect was used by Maya elites, and nobles had to pass a test to demonstrate their aptitude in Zuyuan before they could assume rulership (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Marcus Reference Marcus1992:78–79; for a Classic Maya example of a prestige language, see Houston et al. Reference Houston, Robertson and Stuart2000:334–337). Similarly, Aztec nobles used a form of lordly speech called tecpillahtolli. As Frances Kartunnen (Reference Kartunnen, Schroeder, Wood and Haskett1997:301) describes it, in lordly speech “indirection and reversal are all-pervasive. Elaborate courtesy requires that one say the opposite of what one means. … Native intuition cannot help with this; one must be schooled in it.”

Material culture can operate in a similar way: visual information is exchanged on different levels depending on the degree of familiarity (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977). Returning to the Zuyuan case, highly decorated textiles, pottery, and other elements of material culture, in what is termed the “International/Mixteca-Puebla Style,” were exchanged among elites as a means of displaying coded symbols signifying elite identity (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin, Luján, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000; Nicholson Reference Nicholson and Boone1982). Anthony Wonderley (Reference Wonderley1986) has used what he terms “material symbolics” of decorated pottery from Naco, Honduras, to contrast foreign elites using the Mixteca-Puebla style with native resistance characterized by the reinvention of local decorative traditions on Naco Bichrome pottery.

In this article, we consider the topic of female ideology in Postclassic Mexico, using elements of material culture, indigenous depictions, and ethnohistorical sources to suggest patterns of symbolism based on the stereotypically female tasks of spinning and weaving. Linguistic and iconographic evidence suggest a structural equivalence between spinning and weaving tools and male-oriented weapons. For example, weaving battens were associated with machetes, whereas long wooden spindles resembled arrows. Spindle whorls were called ”small shields” and functioned symbolically in childbirth, during which women “captured” newborn babies. Specifically, we use iconography found on spindle whorls from Cholula to develop a lexicon of images that are related to symbolism of the earth/fertility goddess cult as a form of specialized visual communication produced and consumed by women. In the conclusion, we suggest that this parallel between spinning and weaving tools and male weapons may have been an attempt by women to usurp power symbols characteristic of males for rebranding, within the female sphere, as a form of resistance against an evolving power dynamic of male dominance (Klein Reference Klein1994; Nash Reference Nash1978; Rodriguez-Shadow Reference Rodriguez-Shadow and Maria1988).

Female Discourse in Postclassic Mexico

The sixteenth-century Florentine Codex was compiled by the Spanish priest and chronicler Fray Bernardino de Sahagún from native informants, for the most part elite males; therefore, even though it provides an encyclopedic breadth of information on the Aztec world, it cannot be considered comprehensive (Klor de Alva Reference Klor de Alva, de Alva, Nicholson and Keber1988). In fact, several feminist scholars have criticized the androcentric bias found in the text (Brown Reference Brown and Berlo1983; Hellbom Reference Hellbom1967; Joyce Reference Joyce2000: S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty1988, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991), especially by pointing out where the indigenous artists’ drawings contradict the Spanish interpretations. Despite the inherent male bias, Sahagún did record some elements of female practice, including speech. For example, he noted the “very good discourses of the sort which women say; and very good are each of the metaphors” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:151). Book 6, Rhetoric and Moral Philosophy, records the admonitions of female midwives related to prenatal preparations and childbirth, in which “man's talk” was used to address the newborn boy whereas “unintelligible mutterings” were directed to baby girls (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:151–182, 205–208). This would be consistent with a specialized language used to transmit arcane knowledge and to exclude outsiders.

Book 11, Earthly Things, deals with the natural world of the Aztecs, including plants and animals. Although many of the descriptions are brief and to the point, others that deal with food and herb lore are quite elaborate, possibly reproducing a female voice. For example, compare the descriptions of xoxocoyoli (oxalis) versus mexixin (watercress; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 11:138):

Xoxocoyoli: It is sour, edible; edible raw, cookable in an olla.

Mexixin: It burns. Its leaves are small. It is edible uncooked. When much is eaten, it burns one, blisters one. It is cookable in an olla; it can be ground. It can be made into tortillas [or] into tamales called mexixquillaxcalli. … Its seeds are yellow, small but broad, very hard. It is really the food of the servants, and is a medicine for the flux. It expels the flux. They make an atolli from the seeds, which cleans out, moves out the flux which is in the intestines.

Other examples include first-person descriptions of gathering and preparing food, tasks that were probably done by women or servants; for example, “Etenquilitl: I gather etenquilitl. I gather etenquilitl greens. I cook etenquilitl in an olla. I eat etenquilitl” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 11:136).

Notwithstanding these possible exceptions, the ethnohistorical accounts are predominantly male oriented and so provide a distorted and ambiguous perspective on female subculture. We are told that the “good woman” worked diligently in the house, cooking, caring for children, spinning, and weaving (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 10). The umbilical cord of a baby girl was buried beside the household hearth to signify that her place was in the home (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 4:3–4). Such accounts led some scholars to infer that women were subordinated, with little power in Aztec society (Klein Reference Klein1994; Nash Reference Nash1978; Rodriguez-Shadow Reference Rodriguez-Shadow and Maria1988). Others infer a “structural equivalence” or complementarity between male and female genders that included women in positions of both public and domestic authority (Joyce Reference Joyce2000; Kellogg Reference Kellogg, Kathryn Josserand and Dakin1988; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Sweely1999, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty1988, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991). A more nuanced interpretation by Elizabeth Brumfiel (Reference Brumfiel and Wright1996a) contrasts women's roles in public versus domestic contexts to suggest that, although males dominated the public sphere, women had relatively greater authority within the household. Unfortunately, the ethnohistorical information on female practice is limited and generally stereotypical. Reading between the lines of the accounts, especially when informed with archaeological evidence, can enable a more robust vision of prehispanic female practice and symbolic communication.

Spinning and Weaving as Nahua “Whorl-View”

One important domain of female activity was textile production, both the spinning of fiber and the weaving of cloth (Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel, Gero and Conkey1991, Reference Brumfiel1996b; Hendon Reference Hendon2006; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991). Ethnohistorical sources clearly and consistently identify this as women's work: “look well, apply thyself well, to the really womanly task, the spindle whorl, the weaving stick” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:96). In the bathing ritual of newborns, girl children were presented with spinning and weaving tools, in addition to the appropriate clothing associated with female identity (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:Figure 30).

The close relationship between textile production and female identity was reinforced through religion, specifically in the personas of members of the female earth/fertility cult (G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Sweely1999, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991, Reference McCafferty and McCafferty1994; Sullivan Reference Sullivan and Boone1982). Goddesses such as Tlazolteotl, Mayahuel, and especially Xochiquetzal were closely linked with domestic crafts, including spinning and weaving. In precolumbian and colonial pictorial manuscripts these goddesses are portrayed carrying and wearing spinning and weaving tools not simply as utilitarian objects but as symbols of their productive and reproductive power. Spinning and weaving were metaphors for sexual reproduction, as described by Sullivan (Reference Sullivan and Boone1982:14):

Spinning goes through stages of growth and decline, waxing and waning, similar to those of a child-bearing woman. The spindle set in the spindle whorl is symbolic of coitus, and thread, as it winds around the spindle, symbolizes the growing fetus. … Weaving, too, the intertwining of threads, is symbolic of coitus, and thus spinning and weaving represent life, death, and rebirth in a continuing cycle that characterizes the essential nature of the Mother Goddess.

Goddesses with spinning and weaving tools are represented as midwives, metaphorically taking captives: “And when the baby had arrived on earth, then the midwife shouted; she gave war cries, which meant that the little woman had fought a good battle, had become a brave warrior, had taken a captive, had captured a baby” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:167). Women who died in childbirth were accorded honors similar to those given to warriors who died in battle and were destined to ascend into the heavens to accompany the sun on its daily journey (6:162). At night they returned to haunt the living while searching for their lost spinning and weaving tools (6:163).

Spinning and weaving tools were incorporated as insignia of members of the earth/fertility goddess complex, symbolizing their role as patronesses of the arts, particularly of the domestic arts associated with women. Members of the goddess complex melded symbolism of domestic production with sexual reproduction. Both became arenas for the negotiation of female power within the household: women gained prestige by bearing children and through skilled management of household affairs and weaving expertise. The metaphor is made explicit in the Nahua riddle (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:240; paraphrased in Sullivan Reference Sullivan and Boone1982:14): “What is it that they make pregnant, that they make big with child in the dancing place?” The answer, “a spindle,” refers to the ball of thread winding around the spindle shaft, whereas the “dancing place” refers to the little bowl where the end of the spindle shaft rested during supported spinning.

We have been investigating Nahua spinning and weaving for the past 25 years, using ethnohistorical, ethnographic, archaeological, and art-historical perspectives (G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty1988, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991, Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2000). One finding that has consistently surprised us is the pervasiveness of spindle whorls, or malacates, as metaphorical devices. For example, plants, teeth, flowers, trees, and sacrificial stones are all described as having qualities that are “whorl-like.” Molars and nopal cactus fruits are round like a spindle whorl (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 10:109, Book 11:122), and the head of the çacananacatl mushroom is flat like a spindle whorl (11:132). Willow trees become like a spindle whorl as they fill out and their branches hang down (11:110). The yopixochitl flower “has a pistil; it is like a spindle whorl” (11:209).

The gladiatorial stone of ritual sacrifice was known as the temalacatl, literally “stone” + “spindle whorl” in the Nahuatl language. The temalacatl is a large round stone, perforated in the center. It was dedicated in a ritual in which “Singers of the Round Stone” performed, wearing “round ornaments shaped like millstones, with a hole in the middle, all made of white feather-work” (Durán Reference Durán1971 [1576–1579]:171–172). During the Tlacaxipehualiztli festival's sacrificial rites, captive warriors were tied by the ankle to the center of the stone and given effigy weapons made of feathers in place of obsidian blades with which to defend themselves from fully armed warriors (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. (a) Sacrificial victim on temalacatl stone (drawn from Codex Magliabechiano Reference Nuttall1983); (b) hill glyph (Codex Nuttall 1975); (c) woman spinning as toponym (Codex Vindobonensis 1992).

Further study of the ceremonial use of the large sacrificial stones indicates that they, in fact, served metaphorically as monumental spindle whorls. After heart sacrifices, a long pole with a paper serpent twisted about it (like a spindle wound with fiber) was erected in the center hole and burned (Durán Reference Durán1971 [1576–1579]:190–191; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 2:147). The sacrificial victims wore paper crowns from which “little shields” were hung. The paper serpent was the symbolic representation of Huitzilopochtli's xiuhcoatl, or fire serpent, and the little shields worn by the sacrificial victims could have been the tehuehuelli shields characteristic of Huitzilopochtli (the Aztec's patron war god)—or perhaps they could have been decorated spindle whorls that, as noted later, were often decorated with the pattern most diagnostic of the war god.

The term temalacatl was also used in reference to the stone rings used in the ballgame. A ballcourt depicted in the Codex Magliabechiano (Reference Nuttall1983:161) features stone rings decorated in the same way as archaeological spindle whorls, with claw motifs on the corners of the ballcourt structure that identify the building with the skeletal earth goddess Tlaltecuhtli. In the Mixtec Codex Vindobonensis (1992:13, 20, 22), rubber balls and spindles with whorls and spun fiber are depicted in association with ballcourts. Rubber balls used in the ballgame may have been conceptually linked to spun fiber, because they were made of tightly wrapped strands similar to balls of yarn.

Spindles with whorls were a prominent image used in pictorial manuscripts both in toponyms and as costume elements. For example, the Codex Nuttall (1975:48–4) shows a place glyph of a mountain with a cleft represented as a vulva and with two spindles projecting from the top (Figure 1b). The Codex Vindobonensis (1992:9) shows a woman spinning between two hills as a place sign (Figure 1c). The Codex Nuttall (1975:11–12) also represents a spindle with whorl at the base of one of two snow-covered mountains; the snow-covered volcanoes of Popocatepetl and Ixtaccihuatl are prominent features in Central Mexico and readily visible from Cholula. Malacatepec (literally “hill of the spindle whorl”), a town south of Cholula, probably would have had a hill with a spindle as its place glyph and is depicted as such in the Historia Tolteca–Chichimeca (1976 [1547–1560]).

Female deities of the earth/fertility complex are identified in the codices with a variety of spinning and weaving associations, including spindles, battens, whorls, and unspun cotton fiber (Figure 2a-b). Codices of the Borgia Group (1963) consistently identify the goddess Tlazolteotl with a headdress of unspun fiber and with spindles tucked into the headdress, whereas Cihuacoatl and Xochiquetzal are depicted carrying weaving battens in Nahua pictorial manuscripts of the Contact period. Note that prominent weavers from the Oaxacan coast are still known as malacateras (spinners) and wear spindles in their hair as a symbol of their prowess. In the Mixtec Codex Nuttall (1975:34–35), women associated with the Zaachila lineage carry spindles with whorls as symbolic standards of authority (Hamann Reference Hamann, Claassen and Joyce1997), and a batten and spindle are carried by Lady 13 Flower, a goddess with costume elements similar to Xochiquetzal (Codex Nuttall 1975:19).

In addition to these straightforward representations of spinning and weaving tools, the codices also depict spindles in more complex situations. For example, the Codex Nuttall (1975:6-3, 10-12) twice shows the supernatural Lady 9 Monkey associated with a hummingbird/spindle, in which the beak is an extension of the spindle as if the two are equated metaphorically (Figure 2c). The association between hummingbirds and spinning is also suggested by a small polychrome spinning bowl from the Zapotec site of Zaachila that features a small hummingbird perched on the rim.

Weapons of Resistance?

In addition to these examples, a metaphorical relationship existed between male weapons and female weaving tools (S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991). Wooden battens were used to separate the warp strings on a loom to allow the shuttle to pass through to form the weft while weaving. In Nahuatl, they are called a tzotzopaztli, or “weaving sword” (Berdan Reference Berdan1987). In Spanish they are called simply machetes (Garcia Valencia Reference Garcia Valencia1975). Thus, weaving battens clearly carry at least a linguistic metaphor as a weapon. Additional evidence from ethnohistorical sources indicates that this metaphor carried over into ritual practice. In the prehispanic Atemoztli ritual, battens were used to slice open dough effigies as a form of sacrifice (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 2:29): “They opened their breasts with a tzotzopaztli, which is an instrument with which women weave, almost like a machete; and they took out their hearts and struck off their heads,” and then the effigy was eaten.

Battens were carried as part of the identity of several aspects of the Mother Goddess complex, especially Cihuacoatl and Ilamatecuhtli (Figure 3a); Cihuacoatl is even described as carrying a “turquoise [mosaic] weaving stick” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 1:11), which is reminiscent of a carved bone batten found at Monte Alban Tomb 7 that was inlaid with turquoise (Caso Reference Caso1969; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Nelson2003). These goddesses were associated with warfare and death, especially from the perspective of the life/death cycle (Klein Reference Klein, Kathryn Josserand and Dakin1988). On the Aztec Tizoc Stone (as well as the Cuauhxicalli Stone), paired individuals depict the Aztec king holding a defeated ruler by the forelock to indicate conquest. Most of the pairs depict conquered male rulers who hold a bundle of spears and a spear thrower, but in two cases female rulers are represented, and they hold weaving battens as substitutes for male weapons (Figure 3b). A statue of a female parallels Aztec statues of male warriors; its features include a butterfly pectoral and the substitution of a batten for a weapon. A carved shell oyohualli pectoral, probably of Gulf Coast origin, also depicts women holding battens as substitutes for male weapons (Leullier Snedeker et al. Reference Leullier Snedeker, Keller and McCafferty2008).

Figure 3. (a) Cihuacoatl with weaving batten (Codex Magliabechiano Reference Nuttall1983); (b) Tizoc Stone; (c) Xochiquetzal with weaving tools as weapons (Codex Cospi 1994).

Weaving battens themselves are formidable weapons: they are made of hardwood, are usually close to 1 m in length, and are worn to a sharp edge. In Cholula, we observed a woman open a coconut with a single blow of her batten, wielded like a machete (the young woman was then chastised by an older woman for misusing her batten). The metaphorical substitution of battens and machetes continues in Mixtec tradition, where it is said that a boy who is struck by a batten will become impotent, just as a girl will become infertile if touched by a machete (Monaghan Reference Monaghan and Klein2001).

Because of the poor preservation of wood and bone implements, few battens have survived into the archaeological record, but the contextual and stylistic evidence of the few that have survived strongly support their symbolic importance. An effigy batten made of chipped stone was found in a cache at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan/Mexico City (Nagao Reference Nagao1985:Figure 33b). Greenstone battens, some with detailed incised iconography, have been found in the far south of Mesoamerica, in Costa Rica and Nicaragua (Lange Reference Lange and Lange1993). Miniature bone battens with elaborate codex-style engraving were found in Monte Alban Tomb 7 and Zaachila Tomb 1 (Gallegos Ruiz Reference Gallegos Ruiz1978; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Nelson2003; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, Nicholson and Keber1994).

An example from the dry caves of the Tehuacan Valley was described by Irmegard Johnson de Weitlaner (Reference Johnson de Weitlaner, Ekholm, Bernal and Wauchope1971:306) as “a small, perfectly preserved weaving sword, with incised pattern along its upper edge and round seeds within a slot” that would have made a sound like a “rain stick” when used. Its elaborate decoration suggest that this object had a ceremonial function (Johnson de Weitlaner Reference Johnson de Weitlaner1960:75–84). As a possible parallel, Sahagún (Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 2:81) notes that a “sorcerer's staff,” also known as a “mist rattleboard,” rattled when wielded by an old priest. The presence of the ritual batten in a cave provides a context that can be related to female ritual and the earth/fertility cult. Caves were considered to be openings into the underworld and to be the domain of women, and cave openings were depicted in the Mixtec codices as vulvas (Milbrath Reference Milbrath and Miller1988). Ethnographic evidence from Chiapas records the myth that witches lived in caves and spent their time endlessly spinning (Cordry and Cordry Reference Cordry and Cordry1964).

Another parallel between weapons and weaving tools is seen in the Codex Cospi (1994:25), in which the goddess Xochiquetzal is shown holding a spear thrower, but with a spindle substituting for the actual spear (Figure 3c). Ethnographic spindles of the Otomi are shaped like arrows with a carved point at one end (Sayer Reference Sayer1985), which may continue this metaphorical association and also serve functionally to guide the fiber during drop-spinning. A similar parallel is represented in the Codex Vindobonensis (1992:37–2) origin story where the birth tree is divided into two complementary sides: one featuring arrows and the other holding spindle whorls.

The metaphorical link between textile tools and weapons is also seen in spindle whorls, which function as flywheels for processing raw fiber into thread. They are generally made of baked clay, in a disk form with a hole in the center to accommodate a slender wooden spindle (Figure 4). Whorls are often decorated with molded impressions and can also be slipped, painted, or incised, suggesting that they carried symbolic significance in addition to being functional. As described in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:160), the woman in labor is admonished to “take up the little shield” for her battle. The term used for “little shield” is tehuehuelli, in contrast to chimalli, the word commonly used for a war shield. The tehuehuelli is identified as a particular style of shield that is characteristic of the war god Huitzilopochtli and features feather tufts around its edges, often in a quincunx pattern. Spindle whorls may act as a metaphor for childbirth: “the little shield that is for the gladness of the sun” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:204). In reference to the tehuehuelli associated with childbirth, Sahagún (Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 6:97) notes that “all the little shields [could] rest in thy hand.” We previously noted similarities between spindle whorl patterns and decorations found on shields from late precontact and colonial pictorial manuscripts and consequently suggested that the “small shields” may in fact have been spindle whorls (G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Sweely1999, Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991).

Figure 4. Spinning using spindle and spindle whorl (Charnay Reference Charnay, Gonino and Conant1887).

Archaeological Spindle Whorls from Postclassic Cholula

Archaeological spindle whorls have generally been studied from a functional perspective, because they relate to the production of thread from raw fiber; therefore, they are a means of inferring textile production. The pioneering study of whorls from Central Mexico was done by Mary H. Parsons (Reference Parsons, Parsons, Spence and Parsons1972), who classified whorls based on attributes of size and mass to distinguish between maguey or cotton production. Many others have followed in her footsteps, because textile production has become a prominent means for inferring the Mesoamerican political economy (Ardren et al. Reference Ardren, Kam Manahan, Wesp and Alonso2010; Beaudry-Corbett and McCafferty Reference Beaudry-Corbett, McCafferty and Ardren2002; Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel, Gero and Conkey1991, Reference Brumfiel1996b; Chase et al. Reference Chase, Chase, Zorn and Teeter2008; Halperin Reference Halperin2008; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2000, Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2008; Nichols et al. Reference Nichols, McLaughlin and Benton2000; Smith and Hirth Reference Smith and Hirth1988; Stark et al. Reference Stark, Heller and Ohnersorgen1998; Voorhies Reference Voorhies and Voorhies1989). Yet despite the fact that most of these authors acknowledge the relationship between women's activities and textile production, the explicit investigation of the symbolic dimension of this relationship has only been minimally developed (Ardren et al. Reference Ardren, Kam Manahan, Wesp and Alonso2010; Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel2006, Reference Brumfiel2007; Enciso Reference Enciso1971; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Nichols and Pool2012; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty, Schevill, Berlo and Dwyer1991, Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2000).

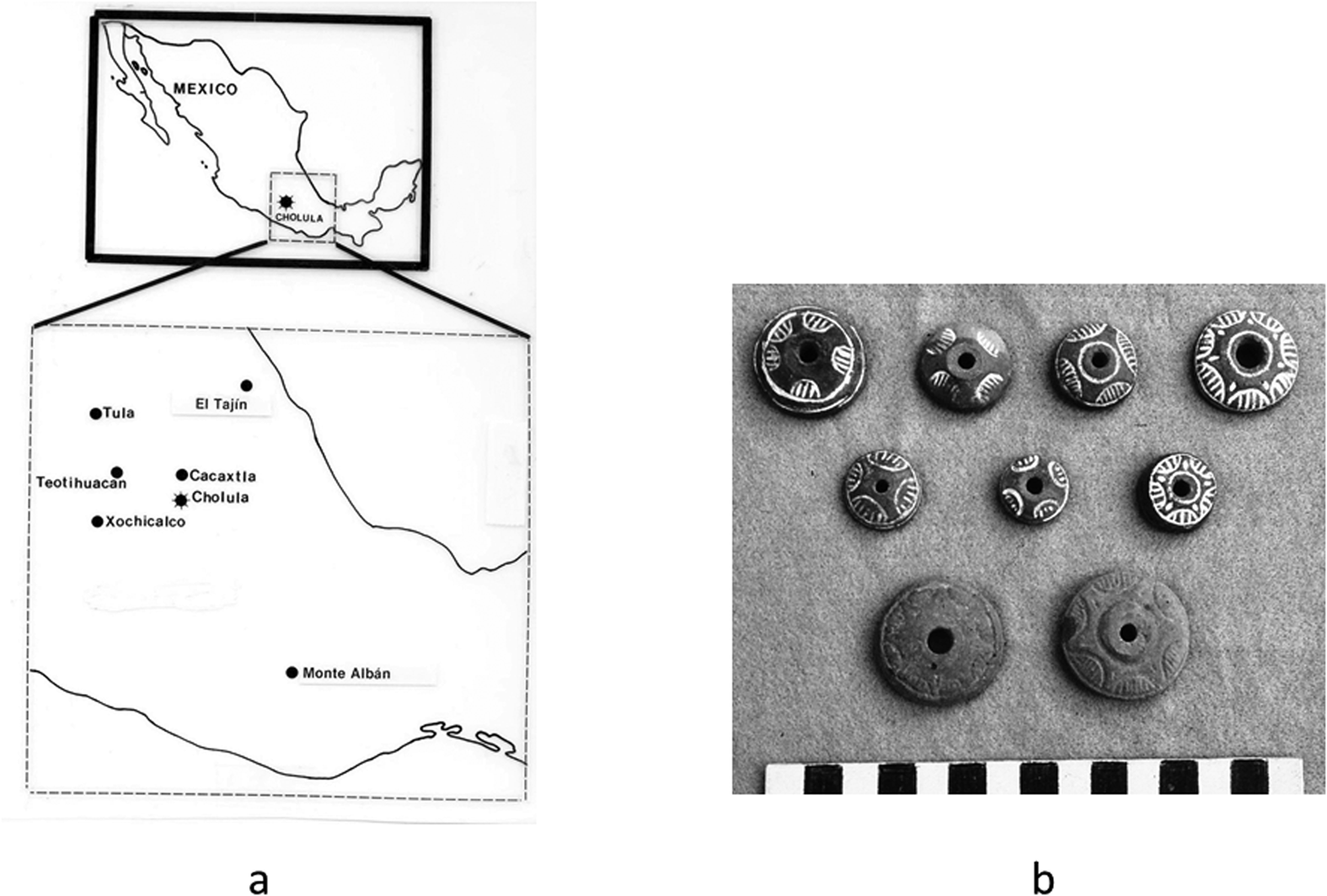

The strong connection between spinning and weaving tools and female identity, at least in the Postclassic period (AD 900–1520) of Central Mexico, allows for speculation on the use of these objects in relation to female symbolic communication. An extensive corpus of spindle whorls from Postclassic Cholula (Puebla) provides an exceptional database for study (Figure 5b). Cholula was a major urban center in the central highlands of Mexico, with great religious and economic importance (McCafferty Reference McCafferty, Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001a; Figure 5a). Occupied since at least the Middle Formative period (ca. 1000 BC), it had a population of 30,000–50,000 people in the Postclassic and was one of the most powerful city-states in the region. Although it was never part of the Aztec Empire, a prominent component of its Late Postclassic population was Nahua, the same ethnic group as the Aztecs, and so Sahagún's observations are at least partially relevant. Cholula was an artisan center for the production of pottery using the Mixteca-Puebla style and also was the source of elaborate textiles (McCafferty Reference McCafferty, Nicholson and Keber1994, Reference McCafferty2001b; S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2000).

Figure 5. (a) Map showing location of Cholula, Mexico; (b) spindle whorls from Postclassic Cholula.

Cholula has a long history of archaeological exploration (McCafferty Reference McCafferty1996; Marquina Reference Marquina1970). In the 1960s and early 1970s the Proyecto Cholula conducted extensive excavations into and around the base of the Great Pyramid, Tlachihualtepetl. In the process, hundreds of spindle whorls were recovered. Other excavations in the city also recovered whorls, notably the UA-1 excavation of an Early Postclassic house and surroundings (McCafferty Reference McCafferty1992), a Late Postclassic midden from UA-79, and a Late Postclassic burial with many individuals associated with spindle whorls (Suárez Cruz Reference Suárez Cruz1989). We have used these materials to interpret textile production at Cholula (S. D. McCafferty and G. G. McCafferty Reference McCafferty and McCafferty2000), and in 1998 we conducted a detailed analysis of approximately 800 additional whorls from the Proyecto Cholula collections. Based on such morphological criteria as diameter, height, mass, and hole size, one can make inferences about how the whorl functioned, including the possible fiber that was spun, the spinning method employed, and the characteristics of the finished product.

Of the Cholula whorls, more than half are decorated, mainly with mold-impressed designs. We argue that spindle whorl decorations present a distinctly female-oriented iconography and thus provide an opportunity to study female symbolic communication. In our design analysis we distinguished between anthropomorphic/zoomorphic, botanical, and geometric motifs. Within each of these major groupings are smaller divisions, or “types.” After defining these different types, we compared them with other sources of imagery, including shields, painted manuscripts, and ceramic artifacts. Shields are a particularly good source of comparison because they were often described in the Florentine Codex, the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993), and the Codex Mendoza (Anawalt Reference Anawalt1992), with Nahuatl glosses to identify patterns and other contextual associations.

Cholula spindle whorl patterns rarely feature human subjects, although “were–human/animal” figures exist (Figure 6a–c). Avians are the major subject of zoomorphic imagery, depicted either in profile, in plan view, or segmented (Figure 6d–f). The artists place emphasis on the head, wings, and tail feathers. A raptorial hooked beak is typical, perhaps recalling the midwife's admonition to the woman in labor to be “like an eagle warrior” while clutching her little shields. During the bathing ceremony, the newborn is described as “the tail feather, the wing feather” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]: Book 6:176) as he or she is presented to Chalchiutlicue, an aspect of the goddess particularly related to childbirth. Small offerings, possibly including spindle whorls, were deposited in springs and wells as petitions to the goddess for pregnancy (Durán Reference Durán1971 [1576–1579]:269). The whorl decoration of wing and tail feathers may be related to this practice.

Figure 6. (a–c) Anthropomorphic designs on spindle whorls; (d–f) avian designs on spindle whorls.

Botanical motifs are quite common on spindle whorls from the Cholula collection (see McMeekin Reference McMeekin1992). Plants and flowers are both depicted, usually in plan view. Motifs vary from simple to complex, multielement patterns. Some patterns incorporate geometric elements into the floral motif. Some representations of leaves and petals form a central motif of four-pointed petals, with detailed leaves and tendrils in the space between the petals (Figure 7a–d). This pattern is similar to a representation of the teccizuacalxochitl flower (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]: Book 11:209, Figure 710), which is also known as the “palace flower” or “adultery flower” (G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Sweely1999; Figure 7e–f). In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (1979 [1550]:Plate 45), Malintzin carries a shield with a similar pattern. A related plant, the huacalxochitl, or “basket flower,” has a similar leaf and curlicue. This flower may be represented on the huipil (blouse) of Malintzin (Muñoz Camargo Reference Muñoz Camargo1981:ff. 248v, 23).

Figure 7. (a–d) Plant and flower imagery; (e–f) palace flower imagery; (g–j) floral imagery; (k–l) marigold imagery; (m) goddess Chicomecoatl; (n) sunflower imagery.

Flowers were an essential part of Mesoamerican ritual and were used in ceremonies for both male and female deities (Heyden Reference Heyden1985). The goddess Xochiquetzal, literally “precious flower,” was closely associated with both the domestic and the sexual arts. In Aztec myth, flowers were created when a bat (made from the semen of Quetzalcoatl) traveled to the paradise of Tamoanchan and bit Xochiquetzal on her “sex organ” (Boone Reference Boone1983:206; G. G. McCafferty and S. D. McCafferty Reference McCafferty, McCafferty and Sweely1999). As a result, flowers came to represent all sensual delights, including love, art, and music. Flowers were also used for their medicinal properties by midwives and other followers of the goddess cult. Whorls with floral motifs are well represented in the botanical group (Figure 7g–j). The hole in the whorl becomes the flower's center, with the petals radiating around it. The number and shape of the petals vary, as does the detailing of the petals. Petals may be squared, rounded, or pointed. There can be as few as four petals or multiple petals in rings circling the center hole.

A particular flower that appears often on Cholula spindle whorls is the marigold (Tagetes sp.), known in Nahuatl as the cempoalxochitl (Figure 7k–l). The flower can be identified by its yellow/orange color and the jagged and serrated edges of the petals. Whorls with double-petal rows and zigzag elements may be representations of the marigold. The plant is important for its ritual, medicinal, and culinary uses, as well as its aromatic properties when both its leaves and flowers are used. The marigold has a prominent ritual use in modern Cholula, where it is symbolic of the Day of the Dead in early November; fields surrounding the Great Pyramid are planted with marigolds in preparation for the celebration. In prehispanic times they were similarly associated with the Ochpaniztli ceremony, when women performed the “hand-waving dance” in which they waved bunches of marigolds (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 2:118–119). Women affiliated with the goddess complex, including female physicians, midwives, and “pleasure girls,” participated in a mock battle among themselves, pelting each other with balls of Spanish moss, reeds, cactus, and marigolds.

Another flower that occurs as a whorl pattern is the sunflower, or chimalxochitl (literally “shield flower,” using the more typical word chimalli for “shield”). The goddess Chicomecoatl carries a shield with an eight-petal flower in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:262r; Figure 7m) that was identified as a tonalochimalli or, in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 1) as the tonatiuhchimale, translated as a “sun shield” (1:13). The Cholula whorls feature similar imagery in several examples, ranging from more botanically accurate to more stylized (Figure 7n).

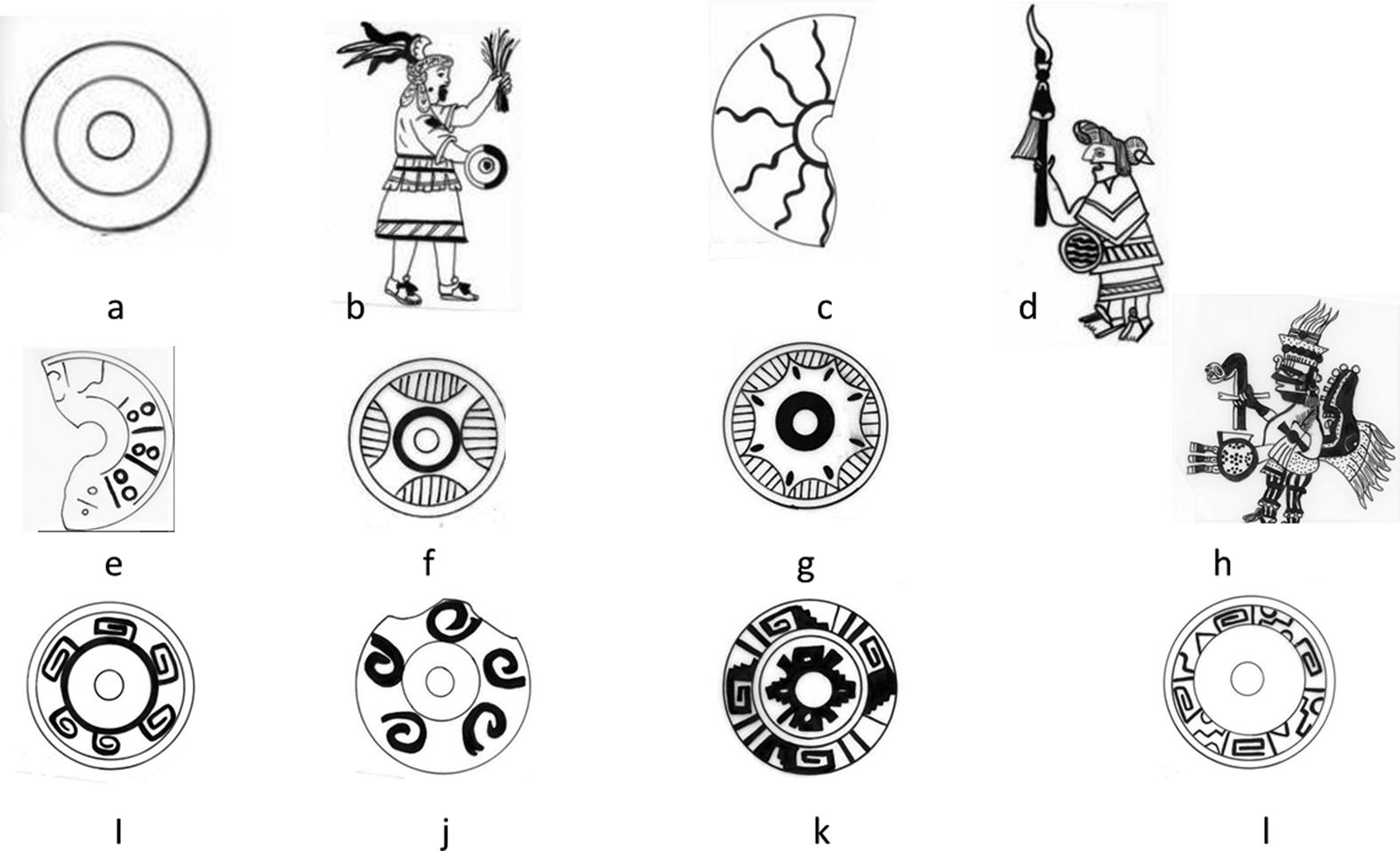

The greatest number and variety of whorl patterns fall into the geometric category and range from simple to complex. One of the simplest patterns features concentric circles around the center hole (Figure 8a). This pattern is characteristic of the shield of the old goddess Toci/Teteo Innan/Ilamatecuhtli. Sahagún (Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982 [1547–1585]:Book 1:16) records that “[Toci's] golden shield was perforated in the center” like a spindle whorl (Figure 8b).

Figure 8. (a) Concentric circle motif; (b) goddess Toci with shield of concentric circle motif; (c) wavy line motif; (d) goddess Xilonen with shield of wavy line motif; (e) radiating line and dot motif; (f–g) hatched semicircle motif'; (h) god Huitzilopochtli with tehuehuelli shield; (i–j) spiral fret motif; (k–l) stepped fret, or xicalcoliuhqui, motif.

Some whorls have wavy lines radiating out from the center hole (Figure 8c). Wavy lines may signify “shiny” or “water.” This pattern is found in association with several members of the goddess complex, including Cihuacoatl, Chicomecoatl, and Chalchiutlicue. Xilonen, a goddess associated with corn, carries a shield with wavy lines (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:ff. 263v; Figure 8d), though they do not radiate from the center.

Whorls may also have a combination of radiating lines and dots (Figure 8e). In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (1979 [1550]:Plate 22), Malintzin carries a sword and a shield with this pattern during the assault on Tepotzotlan.

One of the most common whorl designs features semicircular elements arranged around the edge of the whorl. The semicircles are the consistent design element, within which the configuration of the elements often forms an interior pattern ranging from a cross to a multipoint “star” (Figure 8f–g). Some examples feature additional decoration in the central area around the hole. The semicircles themselves are often embellished with hatched lines, in a pattern reminiscent of the feather tufts that occur on the tehuehuelli shield carried by Huitzilopochtli (Figure 8h) and by warriors in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. Durán (Reference Durán1971 [1576–1579]:72–73) described this shield as having feathers arranged to create a pattern of a cross.

Spiral frets comprise another major design group, which can range from simple to more complex (Figure 8i–l). The fret motif is used to indicate water in Nahua iconography; in other cases it represents a cut conch shell that was a diagnostic symbol of Quetzalcoatl, the principal deity venerated in Postclassic Cholula. The more complex stepped fret, or xicalcoliuhqui, is a characteristic of the merchant god Yiacatecuhtli, an avatar of Quetzalcoatl. The spiral fret pattern is also used as a decorative costume element; for example, on the skirt of Malintzin as she directed the attack on Cholula (Lienzo de Tlaxcala 1979 [1550]:Plate 9).

Conclusion

In this article we argue that objects associated with the diagnostically feminine crafts of spinning and weaving carry iconographic messages relating to an explicitly female pattern of symbolic communication. The spindle whorls of Postclassic Cholula exhibit an extensive corpus of signs. Cholula was one of the principal centers for the international Mixteca-Puebla stylistic tradition, and so pictorial manuscripts and other aspects of the tradition can be useful in interpreting the symbolic meanings codified in the whorls.

Numerous whorl patterns relate to the shields carried by Postclassic goddesses, especially those represented in the early colonial codices illustrated by indigenous artists. We therefore suggest that spindle whorl patterns provide another “voice” from the precolumbian past, in contrast to more androcentric texts recorded by Spanish priests using elite male informants or in imagery communicated on more public art. Listening carefully to the “mutterings” of these objects of domestic material culture, one can interpret a distinctively female discourse.

By incorporating shield patterns on spindle whorls, women identified with the Mother Goddess complex and other powerful women and thus engaged in a conversation about female power. Through the use of symbols of power incorporated on such common elements as whorls, women were able to express their gender identity, as well as a form of resistance through the subversion of male emblems (e.g., shield motifs) onto a medium that was expressly female. In this regard, a spindle with a whorl would be a plausible emblem for female power, as indicated by its depiction in association with deities in the codices, as well as being a formidable weapon in its own right (comparable to a 12-inch hatpin). In precolumbian pictorial manuscripts, goddesses are represented holding spinning and weaving tools in postures that parallel males using spear throwers, suggesting a “structural equivalence” similar to that which Susan Kellogg (Reference Kellogg, Kathryn Josserand and Dakin1988) has generalized for Aztec gender relations.

It should be noted that whorl designs and the context of decoration varied greatly between the different regions of Central Mexico, suggesting that this format was dynamic and that other areas should be analyzed to identify alternative messages or media of symbolic communication. For example, Elizabeth Brumfiel (Reference Brumfiel2006:866, Reference Brumfiel2007) interprets whorl motifs from the Basin of Mexico as relating to solar imagery, symbolic of the divine heat of the tonalli. Other whorls from the Valley of Mexico are often decorated with incised cross-hatching in simple geometric patterns (Parsons Reference Parsons, Parsons, Spence and Parsons1972), whereas xicalcoliuhqui frets are the most common motif from Tlaxcala (García Cook and Merino Carrión Reference García Cook and Carrión1974). At Chichen Itza, spindle whorls often feature militaristic eagle and jaguar motifs, relating to the warrior clans, yet Ardren and colleagues (Reference Ardren, Kam Manahan, Wesp and Alonso2010) found a combination of bird, floral, geometric, and toad imagery on whorls from the secondary site of Xuenkal. Clearly whorls were used to express a variety of messages, and further studies will broaden our understanding of this important artifact class.

Decorated spindle whorls provide a potential means of inferring female symbolic communication, and thus an alternative to the androcentric histories recorded by Spanish chroniclers. Spindle whorls as “little shields,” as well as the other textile production tools with metaphorical parallels to male weapons, served as symbols of female power in direct contrast with established male symbols. These small and relatively ubiquitous artifacts therefore hold strong potential for a more nuanced interpretation of Postclassic Mexican social relations and female gender ideology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sergio Suarez Cruz of the Puebla Regional Center of the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia for allowing access to the spindle whorls of the Proyecto Cholula, in storage at the Museo del Sitio in Cholula. Funding was provided by Brown University (1994) for student participation in the analysis. Variations on this paper have been presented at numerous conferences since 1986, and we thank all the malacatistas who have commented over the years.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact authors for additional information, or see https://antharky.ucalgary.ca/mccafferty/cholula.