1. Introduction

While research has increasingly demonstrated the effectiveness of instruction in the two vital aspects of communicative competence of pronunciation and interlanguage pragmatics (see, for example, Saito Reference Saito2012 for pronunciation and Rose Reference Rose2005 and Takahashi Reference Takahashi2010 for pragmatics), we have seldom brought these together in a way that is of real practical value for language teachers. However, not only do both of these areas play a crucial role in how learners are understood and perceived, but they also interact in ways that impact significantly on the impression that a second language (L2)Footnote 1 user creates when they speak. Just as it is a great pity for learners to say exactly the ‘right thing’ in a way that nobody can understand, so it is of dubious value to be able to say something intelligibly if it is not appropriate for the situation. Yet, while there has been some interest among pronunciation researchers in the relationship of prosody to pragmatic meaning (e.g. Romero-Trillo Reference Romero-Trillo2012), there has been little work in interlanguage pragmatics on the role of pronunciation in the performance of pragmatic aspects of language use.

While most of what follows will be applicable to a wide range of different learners, in this paper I focus on the needs of adults preparing to use L2 English at work. These may be immigrants or other transnationals hoping to join the workforce in a country where they were not raised and through a language that they are acquiring later in life. For such speakers, the ability to create the right impression – the impression they intend to create through English – is vital to their professional, and perhaps also to their personal, success (Burns & Roberts Reference Burns and Roberts2010). Impression management – trying to manage the perceptions that others have of us – is something that we all do every day, but something that is even more challenging in an L2 (Goffman Reference Goffman1959; Bilbow Reference Bilbow1997).

Although the interaction between pronunciation and pragmatics can play a vital role in impression management, these areas rarely get the attention they deserve. My focus here, therefore, is on why and how we should attend to them in both research and practice. I will start by defining what I mean by ‘pronunciation’ and ‘interlanguage pragmatics’ in the context of adult migrants preparing for work, and discuss their importance in managing impressions of who we are and what we intend when speaking a L2. I will then argue that the two areas have commonalities that may make an integrated approach to instruction very beneficial. Drawing on data from a recent study of immigrant professionals, I illustrate how pragmatic and pronunciation difficulties can combine to create a negative impression on interlocutors, and then provide a brief example of how these could be tackled in a classroom setting. I conclude by suggesting not only that we need more research on the interaction between these two aspects of communication, but also that in our profession we urgently need to make sure that the findings of such studies are translated into products that are directly applicable to language teaching practice.

2. Pronunciation and interlanguage pragmatics

‘Pronunciation’ is a lay term that is widely used in language learning and teaching to describe the way utterances are articulated. Although teachers may disagree on exactly which aspects of speech performance are included, the narrow view that it chiefly covers proficiency in segmental aspects of a language (consonant and vowel phonemes) has been largely superseded by a broader view embracing both segmental and suprasegmental (intonation and word/sentence stress) features, fuelling a debate in the literature over the relative merits of regarding each as the primary content of teaching (Derwing, Munro & Wiebe Reference Derwing, Munro and Wiebe1998; Saito Reference Saito2012; Zielinski Reference Zielinski, Reed and Levisforthcoming). However, since the two are highly interdependent in discourse, and the pronunciation of a sound depends crucially on its context (Zielinski Reference Zielinski2008), learners clearly need to pay attention to both. In what follows, therefore, I assume that pronunciation includes attention to at least the following:

-

• sounds and how they fit together in connected speech

-

• stress in words and utterances, and its placement and role in communicating meaning

-

• intonation patterns

-

• pitch/key, range, variation, compared to interlocutor.

In addition, I suggest that other closely related aspects of delivery, such as gaze, gesture, stance and proxemics, are vital for communication (Firth Reference Firth, Avery and Erlich1992; Schmid Mast Reference Schmid Mast2007) and should therefore be treated as part and parcel of what I will call delivery, that is, the way in which something is said. In interaction these features combine with phonological and pragmatic aspects of a speaker's performance to create an impression on an interlocutor, and are therefore crucial to how she or he is perceived (Kerekes Reference Kerekes2007). Used successfully, they can enhance communication, while inappropriate use can increase negative perceptions.

It is important first to consider the nature of our goals for teaching pronunciation and how we can best work towards them, particularly with adult learners, who rarely achieve ‘native-like’ pronunciation (Abrahamsson Reference Abrahamsson2012) and may not want to. However, more achievable goals such as a ‘comfortable intelligibility’ to a native speaker ‘of average good will’ (Abercrombie Reference Abercrombie1956: 37; Fraser Reference Fraser2000: 10) can also be difficult to define and operationalise since ‘intelligibility’ can mean anything from the ability to eventually work out intended meaning, to the ability to achieve full understanding quickly and easily. Work by Derwing, Munro and colleagues (e.g. Derwing & Munro Reference Derwing and Munro1997) has suggested a useful three-way distinction between intelligibility (how far something is understood), comprehensibility (how easy it is to understand) and accent (how far it differs from the target variety of English). Using these related but separate dimensions, the goal of language pronunciation teaching can be operationalised as intelligibility plus comprehensibility – that is, speech that can be understood with relative ease (Derwing & Munro Reference Derwing and Munro2009).

However, the attitude, commitment and background of the interlocutor is crucial here. We have long known about the impact of interlocutors’ attitudes and familiarity on how well they understand speakers with different accents (Gass & Varonis Reference Gass and Varonis1984; Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green2012; Rubin Reference Rubin2012). Our goals for teaching actually depend heavily on the listener as well as on the speaker, and are partly defined by the type of listener a speaker wants to communicate with. Increasingly around the globe this may be a fellow non-native English speaker from what Kachru (Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985) has described as an ‘outer circle’ country (where English is not the native tongue but nevertheless plays a significant or official role) or an ‘expanding circle’ country (where English is neither a native nor an official language, but is sometimes required, perhaps prestigious, and often studied). As a result we have seen a rising interest in goals relating to English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) (e.g. Jenkins, Cogo & Dewey Reference Jenkins, Cogo and Dewey2011). However, for immigrants to ‘inner circle’ countries, such as Australia, Canada and the UK, native speakers are often still the target interlocutors, or at least the gatekeepers to professional success and thus the most important for practical career progression (Kerekes Reference Kerekes2007). In such contexts, therefore, an appropriate goal may be intelligibility to such speakers (Derwing & Munro Reference Derwing and Munro2005; Levis Reference Levis2005; Yates & Springall Reference Yates and Springall2008; Saito Reference Saito2012). As a consequence, although goals for pronunciation teaching do not necessarily orient explicitly to native-like accuracy, there is often a tacit assumption that such norms underlie the models, activities and assessments used.

Moreover, although pronunciation teaching is often de facto treated primarily as a remedial activity, this is to fundamentally misunderstand its basic importance in learning to speak. Spoken language is not the same as written language, and learners do not know how to say something just because they can read it. Activities are therefore required that enable the learning of both spoken and written forms (such as clearly modelling words before they are put on the board, giving students the opportunity to say new items before they write them, marking stress, and practising speaking without the support of written texts), particularly for literate adults whose previous educational experiences may encourage too much reliance on the written word. Pronunciation teaching is very much a proactive activity that should be integrated into virtually all language learning activities from the very beginning (Chela-Flores Reference Chela-Flores2008; Zielinski & Yates Reference Zielinski, Yates and Grant2014), and teacher feedback and regular attention to pronunciation – both as explicit goals and as part of incidental learning – are vital to keeping learners aware of their progress and what they need to do to improve (Yates & Zielinski Reference Yates and Zielinski2009).

Pragmatics, at its most general, can be understood as ‘the study of speaker and hearer meaning created in their joint actions’ (Lo Castro Reference Lo Castro2003: 15) and encompasses a great many specific domains of study. My focus here is on the field of interlanguage pragmatics, as this has provided a range of insights particularly relevant to adults seeking to achieve everyday communicative competence in an L2. Interlanguage pragmatics can be broadly defined as ‘the study of how-to-say-what-to-whom-when’ (Bardovi-Harlig Reference Bardovi-Harlig2013: 68). Research has most often focused on the performance (and sometimes interpretation) of various speech acts such as requests, refusals and compliments by native speakers and learners, providing useful insight into not only how such acts may be performed differently by speakers from different backgrounds, but also how misunderstandings can arise when we apply the norms and understandings of our L1 in the use of an L2 (e.g. Gass & Neu Reference Gass and Neu2006; Martinez-Flor & Usó-Juan Reference Martinez-Flor and Usó-Juan2010; Yates Reference Yates and Trosborg2010a, Reference Yates2010b). This has allowed a focus on interpersonal elements of language, such as softeners, directness and markers of modesty, that contribute to perceptions of politeness across cultures (e.g. Trosborg Reference Trosborg2010). It also allows examination of the role these elements play in how speakers are perceived, and thus in how accurately they communicate their intended meaning (Thomas Reference Thomas1983; Eslami-Rasekh Reference Eslami-Rasekh2005; Gass & Neu Reference Gass and Neu2006; Ishihara & Cohen Reference Ishihara and Cohen2010; Yates Reference Yates and Trosborg2010a).

The use of such interpersonal elements of communication is heavily influenced by the cultural values that speakers share (Kerekes Reference Kerekes2007; Meier Reference Meier2010), so it is important to understand the cultural underpinnings of the choices they make. We must therefore understand both the sociopragmatics – the shared understandings in a language community – and the pragmalinguistics – the linguistic means afforded by a language through which different intentions might be expressed (Thomas Reference Thomas1983). For example, sociopragmatic values that have been associated with a prevalent communicative ethos in Australia include a preference for informality, friendliness and displays of solidarity, and a dislike of taking oneself too seriously or overt displays of hierarchy (Goddard Reference Goddard2009; Dahm & Yates Reference Dahm and Yates2013; Gassner Reference Gassner2013). These communicative values give rise to a fiction of egalitarianism to which speakers regularly orient, and which therefore constitutes an interpretive prism through which the performance of others is judged (Wierzbicka Reference Wierzbicka1997; Peeters Reference Peeters2004; Yates Reference Yates, Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford2005). Speakers of Australian English may therefore see formality or the use of titles by speakers of other languages or other varieties of English as intentionally distancing, and hence judge them as aloof or self-important.

Pragmalinguistically, English is rich in syntactic and lexical resources for expressing deference, politeness and solidarity, and this can sometimes be confusing for learners whose L1 uses other means (e.g. honorifics or diminutives) to express these sentiments (e.g. Trosborg Reference Trosborg2010). Since there is no necessary correspondence between languages in how force is mapped onto form – the same word may exist in two languages but have a different force and be used in a different way – learners cannot necessarily simply translate the use of pragmalinguistic devices from their native language. For example, while a polite request may be commonly formulated using the formula Can you. . .? in English, this form does not have the same force and is not used in the same way in other languages (e.g. Russian). Conversely, while some languages (e.g. Vietnamese or Arabic) offer a choice between different levels of language or range of titles to convey either respect or closeness, this is not the case in English. Learning to convey a level of deference or solidarity that is appropriate through an L2 is therefore a considerable challenge: learners need to understand both how much deference or solidarity it is appropriate to signal, and exactly how to do it. One frustrated learner described these pragmatic dimensions as the ‘secret rules’ of communication (Bardovi-Harlig Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Rose and Kasper2001). And, of course, it is not only necessary to understand what should be done in a context, but also how to do it – and this includes delivery.

3. Research and teaching

As teachers, our goals for both pragmatics and pronunciation teaching should be to help learners not only be understood in the way they intend but also accurately understand other people's intentions. This entails using a pronunciation that is both intelligible and comprehensible and the use of speech acts and pragmatic phenomena in order to create the intended impression, because both how a speaker delivers what they say – their pronunciation (broadly conceived) – and how they choose to express their intentions through the use of pragmatic devices are vital to the impression that they ultimately create. Since talk is collaborative and interactional, meaning resides in how conversational participants use various features and forms as well as in the specific forms themselves (Szczepek Reed Reference Szczepek Reed2012). For learners who want to conduct their professional lives through English, the ability to manage the impressions that they create is crucial for communicative success, so the ability to control both their pronunciation and the interpersonal elements of pragmatics – and the way these interact – is essential. Both should therefore be taught explicitly and in combination from the very beginning of language learning, and yet both have suffered from neglect in the classroom (Ishihara & Cohen Reference Ishihara and Cohen2010; Foote, Holtby & Derwing Reference Foote, Holtby and Derwing2011).

Research on the relationship between pronunciation and pragmatics is also sadly lacking, perhaps due to the increasing specialisation required of researchers competing for ever-diminishing sources of funding. Moreover, reports of pronunciation studies that have focused on the relationship between pronunciation and pragmatics can be rather technical and theoretical in nature, and are therefore not very accessible to a practitioner readership (for example, some of the papers in the recent collection by Romero-Trillo Reference Romero-Trillo2012). They also tend to explore the needs of more proficient, higher-level ‘English major’ students, rather than those of other learner populations. With some honourable exceptions (e.g. Pickering, Hu & Baker Reference Pickering, Hu and Baker2012), the practical pedagogical advice given to teachers on the basis of research findings can be a little thin on the ground, or relegated to the concluding paragraphs almost as an afterthought (as in Riesco-Bernier Reference Riesco-Bernier2012). Similarly, while research from an interlanguage pragmatics perspective has provided useful insights that feed directly into practice through such volumes as the influential Teaching and learning pragmatics (Ishihara & Cohen Reference Ishihara and Cohen2010), attention to pronunciation is noticeably absent (for an overview, see Barron Reference Barron2012).

It seems that the academic specialisation required for careful research militates against the interdisciplinarity that can help teachers to integrate these two crucial aspects of communicative performance. Yet this integration makes sense, both because there are commonalities in the way that the two areas can be approached with adult learners in particular, and because – as I argue next – they are so closely interconnected in the speaking skills needed for success in everyday communication.

4. Some parallels for learners and teachers

While there are different bodies of knowledge and sets of skills to be learned in pronunciation and pragmatics, there are also parallels in the role that they play in the lives of L2 learners, and in the way that teachers can approach these two areas in the classroom. These can be summarised briefly as follows:

-

• Transfer

-

• Awareness: difficulty hearing/understanding differences in self and others

-

• Different understandings of basic concepts

-

• Close relationship of both to a sense of identity

-

• Conscious and unconscious resistance

-

• The necessity of instruction in both from very beginning but often insufficient and ‘sanitised’.

Decades of SLA research have shown that learning is a very creative process, at least as far as the acquisition of syntax is concerned (Ortega Reference Ortega2009; Atkinson Reference Atkinson2011). However, in the acquisition of both pronunciation and pragmatics, transfer seems to be an important consideration, at least for adult learners. By the time they are in their twenties, most adults seem to have set certain parameters which mean that they have much greater difficulty than young children in distinguishing sounds and patterns that are phonetically different from those of their L1 (Best, McRoberts & Sithole Reference Best, McRoberts and Sithole1988; Flege Reference Flege and Strange1995). It is as if the phonology of an L1 becomes a prism through which its speakers interpret the sounds of an L2, and this makes it difficult for them to both hear and master the subtleties of a novel segmental and suprasegmental system (Leather & James Reference Leather and James1991; Flege Reference Flege and Strange1995). For example, although the phenomenon of stress may exist in a speaker's L1, it may be realised differently in English: the contributions of length, force and voicing may be different. Similarly, although voicing may exist in both, the exact timing of the onset of voicing may be different. Indeed, such differences in the way learners understand some of these basic concepts have led to the suggestion that learners should be engaged in critical listening and, together with their teachers, devise a socially constructed metalanguage to bridge these differences (Fraser Reference Fraser2006; Couper Reference Couper2011).

The learning of pragmatics seems similarly inhibited in some way by a learner's prior experiences in a particular lingua-culture. Already familiar with (but not necessarily fully conscious of) a particular way of seeing the world, adults can see the communicative values that they learned as a child as natural and right rather than culturally relative (Thomas Reference Thomas1983). An adult raised in China, for example, where hierarchical terms of address and deference to seniors are highly valued, may find it very difficult to recognise, let alone adopt,Footnote 2 the informality or the syntactically elaborate indirect requests that are often expected by speakers of Australian or American English (Bilbow Reference Bilbow1997; Li Reference Li2000; Yates Reference Yates, Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford2005). The consequences of using the pragmatics of an L1 in the use of an L2, however, can go largely unrecognised, and a speaker can be perceived as rude or bossy rather than simply in the process of acquiring the pragmatics of a new language. Thus the features and use of both pronunciation and pragmatics can be crucial for creating the right impression, and yet difficult to recognise without explicit help.

Accent and pragmatic behaviour and values are crucial to our identity, our sense of who we are and who we align with. Thus the acquisition of a second accent is much more than simply learning another set of sounds or patterns, but is related to deep-seated feelings of comfort or identification with a sense of self and group affiliation (Lybeck Reference Lybeck2002; Marx Reference Marx2002; Gatbonton, Trofimovich & Magid Reference Gatbonton, Trofimovich and Magid2005). Such issues can have a serious impact on a learner's motivation. While for some, particularly high-proficiency L2 learners, wanting to sound like a native speaker is important (Piller Reference Piller2002), for many others the situation is much more complicated. As LeVelle & Levis (Reference LeVelle, Levis, Levis and Moyer2014) argue, the motivation to invest in pronunciation is closely related to the desire to interact and align with a cultural group. By the same token, if we do not wish to be too closely associated with a person or group, we may wish (perhaps unconsciously) to retain the accent from our L1 (e.g. Gatbonton, Trofimovich & Magid Reference Gatbonton, Trofimovich and Magid2005; Gatbonton & Trofimovich Reference Gatbonton and Trofimovich2008): a very good reason for teachers to gain the trust and respect of their learners.

In the same way, if we have grown up believing that certain aspects of pragmatics, such as ways of addressing seniors or subordinates, are ‘natural’ and ‘right’, we can feel very uncomfortable with the idea that we should behave differently. Because these aspects of communication are so deeply held and therefore associated with feelings of who we are and what we believe to be right, the teaching of pragmatics cannot, like the teaching of grammar, provide absolute ‘right’ answers or insist that learners do something in a particular way. Instead, we need to help learners understand that the sociopragmatics and pragmalinguistics of lingua-cultures differ, so they cannot assume that their behaviours will be interpreted in the same way in their new operating environment. Our role is to illustrate the possible impact of behaving in a particular way, and then leave to the learners the choice of how far to make adjustments. They cannot, will never be, and may not wish to be native speakers; instead they must find their own ‘third place’, an English-speaking self somewhere between their previous selves and a native speaker (Kramsch Reference Kramsch1993; Hinkel Reference Hinkel1999). Of course, although pronunciation and pragmatics are interrelated, they are also quite distinct and there are certainly differences in how they are acquired. For example, older L2 learners usually find it particularly difficult to ‘hear’ and recognise unfamiliar phonological features, and often find them not only challenging but also tiring to produce on a regular basis: that is, there is a mechanical component. Moreover, while L2 pronunciation is notoriously difficult to change as an adult, it is not something that most had to attend to in learning their L1. In contrast, most adults have acquired, at least unconsciously, skills in varying pragmatic behaviour according to context, albeit with different degrees of facility and success. However, while they may be unconsciously aware of this as a general principle, they may nevertheless have difficulty with how variation works in a new culture and language and in recognising the pragmatic expectations of the new environments they encounter (Ishihara & Cohen Reference Ishihara and Cohen2010).

5. Teaching pronunciation and pragmatics

As I hope I have demonstrated, both pronunciation and pragmatics must be explicitly taught. Since it can be very much more difficult to help adults unlearn bad habits than to teach them new ones, this should be started from the very beginning of language learning. Despite the inconclusive results of early studies (e.g. Macdonald, Yule & Powers Reference Macdonald, Yule and Powers1994, but see Saito Reference Saito2012), recent research has shown that students who receive pronunciation instruction do better than students who do not (Couper Reference Couper2006; Derwing, Munro & Thompson Reference Derwing, Munro and Thomson2008), and that beginners can also be taught very successfully (Chela-Flores Reference Chela-Flores2008; Zielinski & Yates Reference Zielinski, Yates and Grant2014). Indeed, studies have also found that the pronunciation of long-term immigrants may improve very little without it (Derwing, Munro & Thompson Reference Derwing, Munro and Thomson2008). Studies have similarly demonstrated benefits for instruction in pragmatics (e.g. Bardovi-Harlig Reference Bardovi-Harlig, Rose and Kasper2001; Rose Reference Rose2005; Riddiford & Joe Reference Riddiford and Joe2010).

However, we know from studies on various continents that such instruction is often insufficient (see Gilbert Reference Gilbert2010 for pronunciation and Diepenbroek & Derwing Reference Diepenbroek and Derwing2013 for pragmatics). Where it does occur, it is likely to be highly ‘sanitised’ – that is, drawing on models and activities that focus on citation forms, slow teacher talk or reading aloud for the teaching of pronunciation, and idealised, imagined model interactions rather than naturally occurring connected discourse. Yet attention to these two areas of spoken skills could be very successfully integrated in a teaching approach that encourages reflection and practice on the basis of carefully selected models.

In the remainder of this paper I draw on the analysis of role-play data from two experienced doctors: Fara, from Central Asia, who is seeking to re-establish her career in Australia, and Anne, a native speaker of English who is practising in an Australian hospital. I identify what specific features of pronunciation and pragmatics it might be useful for Fara to focus on, and suggest an instructional approach that could be used to do this.

6. Doctors at work: The study

The data are drawn from a study in which native and non-native English-speaking doctors were invited to a specially set up simulation facility to role-play two medical scenarios common in hospital emergency departments (for further details of the study, see Dahm & Yates Reference Dahm and Yates2013). While all the participants were experienced, only the native speakers were currently practising, as the non-native speakers had not yet passed the clinical examinations required for registration in Australia. These are expensive, and success is highly dependent on good spoken communication as well as medical skills. The aim of the study was to explore how the doctors approached interaction in the same medical scenario in order to identify some of the areas in which they might benefit from specific communications training. The data from this complemented ethnographic explorations of authentic, naturally-occurring doctor discourse (O’Grady et al. Reference O’Grady, Dahm, Roger and Yates2014).

In the scenario from which the two following excerpts are taken, each participant played the role of a doctor who had just come on duty and needed to obtain the details of a case from the nurse who had been handling it. The nurse, Sandra, was played by an actor who was also a part-time nurse. The case involved a child, Aaron, who had broken his leg and had an adverse reaction to a CT scan. Each performance was video-recorded and reviewed by a senior surgeon for comment on the participant's communication and medical skills. It was then transcribed and analysed for various linguistic features. The analysis presented here focuses on the impressions of the surgeon and some of the pronunciation and interpersonal pragmatic features that may have contributed to those impressions, in order to identify what Fara could do to improve her skills in these areas.

The surgeon's first impression of Fara's performance was very negative. He felt she had what he termed an ‘aggressive pronunciation’. On second viewing, however, he softened his earlier position, noting that ‘she does a good and, importantly, a safe job’. Given that first impressions are formed very quickly and are often difficult to dispel, it is instructive to explore what might have contributed to his hasty initial view. An expert in surgery but not in linguistics, his observation notes captured in lay terms the difficulties he had with her communicative style. He noted that she had problems with introductions, ‘stands a bit close and is very still’, has ‘very little inflection in voice’, ‘really does seem to talk fast without getting information across fast’, but that ‘all of the irritating questions are good questions’. In the following analysis I will try to unpack how aspects of her pronunciation and interpersonal pragmatics seem to have combined to give the impression that she was aggressive.

Using a chart designed for use in classrooms to help teachers identify their learners’ pronunciation problems (Yates & Zielinski Reference Yates and Zielinski2009), we analysed Fara's performance in the role-play and identified some of the segmental and prosodic features that may have contributed to the overall impression (see Table 1). From this we can see that she did, as noted by the surgeon, have difficulty with intonation (see also Excerpt 1 below). Combined with little use of stress and sense groups, this made her delivery choppy. She also used full value vowel sounds where native speakers use and expect the reduced vowel ‘schwa’. These issues could well have contributed to the impression noted by the surgeon that she spoke a lot without clearly signalling what should be given priority in what she had to say, and may also have conveyed a sense of rushing. The resultant choppy rhythm, together with the fact that she did not produce the expected degree of aspiration in consonants, and trilled /r/ sounds, in addition to aspects of her stance and body language (see below), may have made her performance seem more forceful than she had intended.

Table 1 Fara's pronunciation difficulties

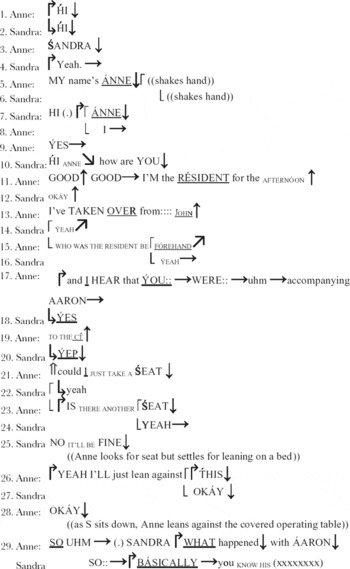

As far as pragmatic issues are concerned, the following excerpt, taken from the opening sequences of her handover from Sandra, illustrates the difficulty Fara had with the greeting sequence (for transcription conventions, see Appendix).

Excerpt 1 Fara: Opening sequence

As can be seen in line 2, in response to Sandra's formulaic initial query ‘how are you’ (a standard greeting sequence in Australian English), Fara's greeting was formal (‘morning’ compared to Sandra's informal ‘hi’), her ritual follow-up greeting was inaccurate (‘how ’bout you’ rather than a reciprocal ‘how are you’) and was delivered with a low pitch accent often associated with information that is extrapropositional information (Wennerstrom Reference Wennerstrom2001: 33). She also paused in lines 4 and 5 as if uncertain how to respond and then repeated the rather formal ‘nice to meet you’. Her choice of opener to request details of the case from Sandra (‘what's the problem’ in line 10) tends to set Fara up as the expert who has arrived to sort out an issue rather than request information, and the trilling and lack of aspiration in her pronunciation of /pr/ in the word ‘problem’ made her delivery sound quite explosive. Each one of these pragmatic and pronunciation features by itself would be very minor and might even have passed unnoticed, but taken together and in the context of other elements of her delivery such as her erect posture, close proximity to Sandra and the aspects of her pronunciation discussed above, she seems to have projected more force or at least more distance than might be expected in this context.

In contrast, consider the opening sequence of the handover scenario between Sandra and Anne, a native speaker.

Excerpt 2 Anne: Opening sequence

A reciprocal informal ‘hi’ is exchanged right away. Anne immediately checks on Sandra's first name, and supplies her own, also offering a handshake. In response to Sandra's greeting move ‘how are you’ in line 10, she supplies a ritual ‘good, good’ and then explains her role and why she is here, something that Fara omitted to do. There then follows a side sequence (lines 21–28) in which Anne casts around for some way to position herself on a level with Sandra to counteract that fact that the latter has been sitting. Not finding a chair, she searches for and finds something to lean on and thereby avoids towering over Sandra as she sits.

Anne's performance also shows some traces of the Australian sociopragmatic values discussed earlier. Her approach is informal and her use of first names, greetings and physical positioning downplays the hierarchical difference between doctor and nurse and reduces social distance between them in a way that Fara's more formal stance and greeting sequence does not. A similar tendency can be seen in their use of other micro-features. For example, while both Anne and Fara use the first person pronoun ‘I’ and ‘we’ to the same extent throughout the handover, they use them differently. Fara noticeably uses ‘I’ more often in fairly bald requests which stress her own needs and wants and in general statements of responsibility, as in:

‘and I want to see the patient [yup] and I want to know about him’

‘because I want to see how is the allergy condition’

‘I have the responsibility after her’

‘first of all I have to check myself the patients’

Anne, on the other hand, uses the first person in moves which mitigate requests, as in:

‘Alright, could I just take a seat?’

‘Is there any other information that y- that I haven't asked or haven't covered you want to tell me’

While Fara regularly uses ‘I’ to establish her position of authority, Anne stresses team work and joint responsibility through the use of the more inclusive ‘we’ when talking about management of the case. From the examples below it can be seen that Fara's statements on management of the case tend to stress her own expertise and responsibility:

But uh let's uh first of all I have to check myself the patients [yes] to see what is the c-[okay] going on [alright]. Uhm At first I will uh see the vital signs is the same like before [yes] as the breathings has okay [yeah] or auscultation [yeah] the auscultation because if there is uh some allergy (condition) [yeah] it can come back [yes sure] that's why it's so important.’

Anne, however, still retains control of the situation, but includes Sandra in subsequent management:

‘We need to have some blood tests and uh:m an anaesthetic consult just to sort of see what they think about’

‘let me just see him and then we go from there’

‘No I think I let me see see the patient [okay] and then we’ll work out where to go’

Pronunciation is crucial here, too. As a non-linguist, the surgeon who evaluated Fara's performance could not fully articulate what feature or combination of features led to this impression, but as linguists we can make some respectable guesses as to the causes. For instance, because Fara does not fully control the placement of stress on words that are important for her meaning, or how not to stress parts of her utterance that are not important, her use of the first person pronoun is particularly salient. Fara not only uses the first person pronoun in ways that tend to stress her own responsibility and role – a stance that is dispreferred in Australian communicative culture (Peeters Reference Peeters2004; Goddard Reference Goddard2009) – but her pronoun usage is even more salient than usual because she fails to use the unstressed variants in places where they would be expected. Thus what she chooses to say and how she says it – her pragmatic choices and her pronunciation – combine to reinforce an impression that she is ‘big-noting’ herself.

In Figure 1 I summarise how pronunciation and pragmatics interact in Fara's case to give an unfortunate and unintended impression of aggression.

Figure 1 The interaction between pronunciation and pragmatics

7. Learning and teaching pronunciation and pragmatics

So what should Fara focus on and how can we help her? Teaching approaches that focus on how features of pronunciation and pragmatics work together to create an impression and which combine awareness-raising activities with opportunities for practice, experimentation and reflection are particularly useful for adults. An example is the prefer approach:

-

• Practice-relevant models

-

• Raising awareness of pragmatic and pronunciation issues and their interaction

-

• Experimentation with new pragmatic resources and pronunciation

-

• Feedback

-

• Exploring the world outside

-

• Reflection on what to do and how to do it.

Central to this approach is the idea that since a learner is not, and never will be, a native speaker, we cannot require them to sound or act like one. Rather, our role as teachers is to provide the information, sensitivity and tools they need to decide for themselves how they want to behave as non-native transnational speakers of English. In order to do this, of course, they still need an appropriate knowledge base from which they can make informed choices. This means understanding the expectations that other speakers will have of them in the domains and contexts where they want to operate, and the consequences of the language choices they make.

Practice-relevant, authentic or semi-authentic samples of discourse are crucial to provide learners with input that accurately reflects the way language is actually used in their target communities. Semi-scripted role-play recordings can offer a viable alternative to naturally occurring authentic language samples, which can be challenging to collect in the quantity and quality required (Yates Reference Yates, Griffin and Guilfoyle2008). Nevertheless, to avoid simply reproducing our own intuitions about professional talk, models should wherever possible be based on evidence from speakers used to communicating in the relevant professional context, even if actors or teachers are used to make the recordings that are used in the classroom.

Activities designed to raise awareness should guide learners to exploit these authentic or semi-authentic models for specific features of pronunciation and pragmatics, and then allow them the opportunity to reflect on how they speak in a similar situation and their feelings about the features they notice. Below I illustrate, by way of example, how an activity sequence might be based on Anne's opening sequence using a prefer approach.

-

• General listening:

-

• Rationale: To establish context, participants.

-

• Sample activity: Listening followed by group discussion of questions: Who's talking? Where? Why? What is their relationship? How do you know this? Would you speak in the same way in this context? Explain.

-

-

• Targeted listening:

-

• Rationale: To guide learners to focus on specific features of pronunciation and pragmatics in context and reflect on why the speakers used them in this way. This will help learners develop the tools they need to identify other features in talk outside the classroom.

-

• Sample activities: Learners listen in order to note the form and delivery of the initial greeting/introductions/use of names or titles etc., perhaps with the assistance of a partial transcript. Class discussion of reflective questions such as: ‘What do they notice about the greeting?’ ‘Would they do it the same way? Why/why not?’ ‘What impression do you think Anne makes? Say why’.

-

-

• Experimentation with, and feedback on, use of features identified:

-

• Rationale: To allow learners opportunities to practise manipulating forms/using the segmental/suprasegmental features identified in the ‘safe’ environment of the classroom, and to receive feedback on their efforts. This can be particularly important when learners are trying to master specific sounds or aspects of prosody such as relative key in conjunction with unfamiliar pragmatic devices.

-

• Sample activity: Controlled practice in the form of dialogue-matching or scripted dialogues followed by freer activities such as short role-plays that allow learners the opportunity to use what they have practised in longer stretches of less controlled, more spontaneous speech. Feedback should take into account learning goals (intelligibility with comprehensibility for pronunciation and accurate impression management for pragmatics).

-

-

• Exploration:

-

• Rationale: To experiment with using these forms and skills outside the classroom and explore how others use them. Since classes cannot cover everything learners need to know, they need to develop tools to identify important communicative features for themselves.

-

• Sample activities: Pronunciation and pragmatic homework ‘noticing’ activities, such as collecting three different greeting sequences they hear outside class and noting not only the forms used but also aspects of delivery such as stressed words and relative key. Short performance tasks which encourage learners to put into practice what they have noticed. For example: ‘Greet three different people using the forms and pronunciation features you have discussed in class’.

-

-

• Reflection:

-

• Rationale: To help learners to reflect on what they have learned from their explorations and experimentations outside the classroom, how they feel about them and why they feel that way in order to help them become more conscious of how they are constructing their ‘third place’. This can help to identify areas of resistance to unfamiliar practices such as using a wider pitch range than they are used to or exchanging reciprocal first names on first meeting with a subordinate at work.

-

• Activity: Pair-work discussions of such questions as: ‘How did you feel when you. . .? Why? What would you normally do?’ ‘What greetings forms were used in the examples you collected? Why?’ ‘How did that sound to you?’.

-

To conclude, as I have argued in this paper, effective communication and impression management involves the integration of a range of speaking skills, including intelligible pronunciation and appropriate pragmatics. Not only do these combine in communication to influence how intentions are interpreted, but each provides a meaningful context for the teaching and learning of the other. It therefore makes sense to teach together what occurs together (Szczepeck Reed Reference Szczepek Reed2012). As I hope I have illustrated, an integrated approach combining these two crucial aspects of interaction is not only vital for learners, but also eminently achievable for teachers. It is time, therefore, that we, researchers and teachers alike, ventured out of our silos to focus attention on how these and other features of talk combine in practice if we are to really help immigrants like Fara to realise their true potential at work.

8. Postscript

Some time has now passed since I gave this plenary, and I have had some time to reflect on the arguments I put forward. Moreover, an oral plenary presentation has a slightly different purpose and, in this case, a more specialised audience than the written version and is less constrained by the need to make a colourful claim with which to open a conference. These considerations and some queries from referees have also led me to consider some of the differences between how pronunciation and pragmatics are learned. While my own practical classroom experience as a teacher has amply illustrated that adult learners find both challenging and that there are very noticeable differences between individuals in the learning of both skills, I certainly concede that there are differences. For example, while ultimate attainment (to borrow the term from SLA) in pronunciation is not likely to be native-like, there does not seem to be the same ceiling on the learning of pragmatics. Moreover, while feedback on performance is useful in both cases, it is more crucial in the learning of pronunciation where specific features may place particular cognitive and physical demands on the learner. This said, however, I still maintain that it is imperative for us to investigate more closely how these two aspects of language interact in the talk of L1 and L2 speakers, and look forward to the development of both research perspectives and teaching approaches that allow a more integrated and multi-modal insight into the nature of communicative competence.

Appendix Transcription conventions from Wennerstrom (Reference Wennerstrom2001)

Pitch accents

Tones associated with salient lexical items.

-

(CAPITAL LETTERS) H*

-

(UNDERLINED CAPITAL LETTERS) L+H*

-

(SUBSCRIPTED CAPITAL LETTERS) L*

-

(SUBSCRIPTED AND UNDERLINED CAPITAL LETTERS) L*+H

Pitch boundaries

-

(↑) High-rising boundaries

-

(↗) Low-rising boundaries

-

(→) Plateau boundaries

-

(↘) Partially falling boundaries

-

(↓) Low boundaries

-

(╸) No pitch boundary or ‘cut off intonation’.

Key

The choice of pitch made at the onset of an utterance to indicate the stance toward the prior one.

-

(↱) High key

-

(→) Mid key

-

(↳) Low key

Paratones

The expansion or compression of pitch range.

-

(⇑) High paratone

-

(⇓) Low paratone

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge financial support for this study from a Macquarie University Seeding Grant, and the expertise of Maria Dahm, Peter Roger and John Cartmill, Agnes Terraschke, Beth Zielinski, Sophia Khan and Sophie Yates. Thanks also to two anonymous reviewers whose comments were invaluable in shaping the final draft.

Lynda Yates is Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistics at Macquarie University, Australia. Her research interests include interlanguage pragmatics, adult language learning and teaching; in particular, spoken language including pronunciation and pragmatics, workplace language, bilingualism, migration and settlement. She has recently completed a large-scale longitudinal study of English language learning and settlement among immigrants to Australia. Her recent publications include two special issues on the teaching and learning of pragmatics: a special Issue of System (forthcoming: co-edited with Eva Alcón-Soler) on Interlanguage pragmatics research across contexts, and one for TESL Canada on the teaching of pragmatics (2013). She has recently published various articles and book chapters with colleagues in the areas of pronunciation teaching and assessment, medical communications training (particularly for internationally trained doctors), bilingualism and the teaching and learning of pragmatics for adult migrants. Her publications also include free, downloadable professional development resources for teachers on pronunciation teaching and assessment, pragmatics, teaching strategies and building confidence in adult learners.