Introduction

“Context” has been increasingly featured and acknowledged in second language (L2) research because L2 teaching is recognised to be shaped by the environments in which it is situated. Numerous theoretical perspectives were introduced to L2 research that aim to capture the contextual forces at work in teaching and learning, including but not limited to Activity Theory, Complexity Theory, and Sociocultural Theory. Activity Theory holds that a learner's motives (human needs directed towards an object) are highly malleable, subject to the influence of such contextual variables as institutional rules, community, tools and artefacts available (see Leont'ev, Reference Leont'ev1978, Reference Leont'ev1981 who popularised Activity Theory from Sergei Rubenstein's founding and also Engeström's more current work in Reference Engeström, Miettinen and Punamäki1999). Complexity Theory, which has been widely adopted in both physical and social sciences, originates from physics (Martin et al., Reference Martin, McQuitty and Morgan2019). Complexity Theory was later introduced into L2 research by Diane Larsen-Freeman who posits that language learning is not only a process but a volatile and emerging system that is shaped by components of the system (e.g., learners, teachers, schools) engaging in constant and vibrant interactions (Larsen-Freeman, Reference Larsen-Freeman, Dörnyei, MacIntyre and Henry2014). Sociocultural Theory highlights the sociocultural contexts where learning takes place (Lantolf, Reference Lantolf2000; Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978). Informed by a social constructivist view of learning, key concepts such as scaffolding (e.g., teachers’ support for learners) are put forward. In particular, Vygotsky argues that communication plays an indispensable role in language learning. Extrapolating Vygotsky's work to L2 research, Swain (Reference Swain and Byrnes2006) claims that languaging, dialogues among learners to discuss issues in L2 learning, is an important process of learning a L2.

These social constructivist theories refer to context in general terms. For instance, Complexity Theory describes the nature of context (one that is volatile and subject to change); Activity Theory examines how learning is mediated by “tools” (e.g., textbooks) and “community”; and Sociocultural Theory focuses on the broader socio-political and cultural landscape where learning and teaching takes place. From the perspective of conceptualisation of context, it appears that there is a need for a more granular view of contexts (as opposed to context as a singular concept), which enables L2 researchers to identify various contextual forces and the interactions among them. It is therefore the purpose of this timeline to offer an alternative theoretical perspective, Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979Footnote *), which has been introduced to L2 research for some time, although receiving less attention. Ecological Systems Theory offers a unique perspective regarding “contexts” because it adopts a more granular and systematic approach to conceptualising contexts than the other theories. Having said that, it must be acknowledged that boundaries between layers of “contexts” are blurry, especially in light of the widespread use of technology in education that enables L2 learning to take place beyond the classroom.

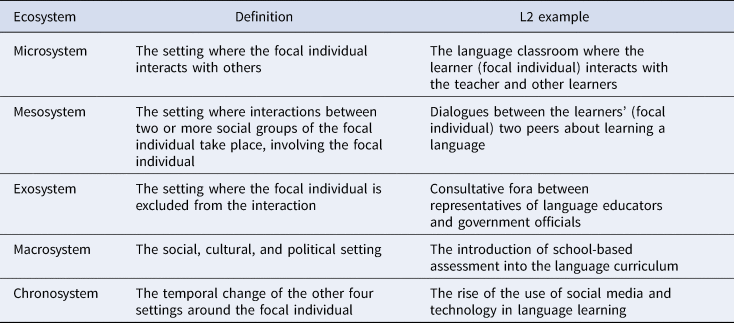

Ecological Systems Theory employs a metaphorical use of the terms “ecology” and “ecosystem” to conceptualise contexts. Ecology is a sub-field of Biology that focuses on the relationships between living organisms and the physical components of the habitats of living organisms, the ecosystem (van Lier, 2014*). In educational research, with the advent of the social constructivist view of learning and teaching, the notion of “ecology” or “ecosystem” has been borrowed by researchers to refer to the environments where learning takes place. An ecological perspective is theorised by Bronfenbrenner (1979*) when he puts forward his seminal nested Ecological Systems Theory framework, which comprises four layers of context: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. Neal and Neal (2013*) further highlight the temporal aspect of context and bring to the fore an additional dimension of context: chronosystem, which was not explicitly mentioned in Bronfenbrenner's book. In the same paper, Neal and Neal put forward a networked version of Ecological Systems Theory. While retaining the five layers of ecosystem, they redefine the notion of “setting” in Bronfenbrenner's (1979*) model. Bronfenbrenner defines “setting” as a location or physical space where people interact. However, given the increasing use of technology in communications, Neal and Neal (2013*) argue that setting is more appropriately understood as face-to-face and virtual interactions among people, focusing on the people rather than places. When presented diagrammatically, a nested Ecological Systems Theory reveals that layers of context form a series of concentric circles, while ecosystems in a networked Ecological Systems Theory are represented by discrete circles, which are connected by the people engaged in interaction in those contexts. In Table 1, we attempt to unpack the meanings of the five ecosystems with an example relevant to L2 learning and teaching.

Table 1. Definitions and examples of the five ecosystems

In social sciences, there has been budding interest in conducting ecologically valid research (Lewkowicz, Reference Lewkowicz2001), for example, in the form of naturalistic classroom-based research. An ecological perspective was introduced to the language education community by van Lier in his 1997 article on adopting an ecological lens to language classroom observation research. van Lier draws on Bronfenbrenner's (1979*) and Gibson's (Reference Gibson1979) seminal work to discuss two approaches to classroom observation: microanalytical (an emic approach to research) and macroanalytical, with the latter referring to Bronfenbrenner's (1979*) four layers of context. van Lier (1997*) also introduces the notion of affordance that refers to the alignment between learners’ needs and environmental design. Following van Lier (1997*), a series of conceptual works were published, discussing various aspects and notions of Ecological Systems Theory, namely, types of interactions between individuals and contexts (Tudor, 2003*), temporal aspect of context (Kramsch, 2008*), an emic approach to research (Lafford, 2009*). These publications laid the groundwork for establishing a firm theoretical and conceptual basis for introducing Ecological Systems Theory into L2 research. Since then, aspects of Ecological Systems Theory have featured in L2 research in various topics, most evidently in the areas of computer-assisted language learning, language policy, language teacher education, and L2 classroom instruction. In this timeline, we aim to include key and recent publications related to the following themes:

-

A. Conceptualisation of an ecological perspective

-

B. Ecological research/perspective on computer-assisted language learning

-

C. Ecological research/perspective on language policy

-

D. Ecological research/perspective on L2 teacher education

-

E. Ecological research/perspective on L2 classroom instruction

-

F. Ecological research/perspective on L2 assessment

Given the transdisciplinary nature of Ecological Systems Theory, selected works vis-à-vis conceptualisation (Theme A) extend beyond L2 research. To make the timeline relevant to L2 researchers, only primary L2 research informed by Ecological Systems Theory is included (Themes B–F). The focus of this timeline is on Ecological Systems Theory and L2 learning and teaching in naturalistic instructional settings that considers sociocultural influences, which is not to be confused with the broader meaning of the term “ecological” in applied linguistics, second language acquisition (SLA), and instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) research. In applied linguistics (especially in sociolinguistics), the term “language ecology” is used synonymously with “linguistic landscape” (for example, see publications in the journal Language Ecology, published by John Benjamins). The notion of “ecology” is also featured in the work of Jay Lemke (Reference Lemke2000) on discourse and social dynamics, Jan Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2010) on timescales in globalised contexts, Uryu et al. (Reference Uryu, Steffensen and Kramsch2014) on the ecology of intercultural interaction, and the field of ecolinguistics (e.g., Bang et al., Reference Bang, Door, Steffensen and Nash2007; Fill & Mühlhäusler, Reference Fill and Mühlhäusler2001; Stibbe, Reference Stibbe2015). In SLA research, the edited volume by Leather and van Dam (Reference Leather and van Dam2003) focuses on ecology and language acquisition that extends to non-instructional contexts. Regarding the established line of SLA research on task-based language teaching, albeit its focus on instructional setting, it rarely considers the role of contexts outside of the language classroom (Long, Reference Long2016). In ISLA, the interpretation of “ecology” is restricted to only classroom settings (in lieu of broader sociocultural settings) and ISLA research focuses on efficacy of pedagogical interventions rather than how contextual forces influence language acquisition (Loewen, Reference Loewen2014). In short, although we are aware of the connotative meaning of “ecology”, the inclusion of this body of important work is beyond the remit of our timeline.

When selecting the entries to be included in the timeline, we consider importance of the publications, that is, classic work frequently cited in L2 research that adopts an ecological perspective (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979*; van Lier, 1997*). More recent publications are also included, including a number that were published in 2021, to demonstrate the growing use of the theory in various sub-fields of applied linguistics. It must be noted that despite the long history of development of Ecological Systems Theory since 1979, its application to L2 research has only been recently taken up, resulting in a prolific growth in the amount of L2 ecological research in post-2019, especially in 2021.

When selecting L2 primary studies that employ Ecological Systems Theory, we take into account depth and explicitness of discussions of Ecological Systems Theory in the publications. In other words, we do not automatically include a publication that claims to adopt an ecological approach; rather, we review publications and include those that dedicate specific sections of the manuscript to discussing Ecological Systems Theory or its components. Another criterion for including L2 primary research is its substantive focus: we would like to include publications from a variety of sub-fields in L2 research to illustrate applications of (aspects of) the theory.

In the research timeline below, which contains 31 entries published between 1979 and 2021, in addition to summarising the original contributions of each piece of work, relationships among the works are highlighted through small capitals whenever possible to demonstrate developments in the conceptualisation, operationalisation, and/or evaluation of L2 learning ecologies. From the timeline, there has been a widespread uptake of Ecological Systems Theory in L2 research, especially in areas related to computer-assisted language learning, language policy, L2 teacher education, L2 classroom instruction, and L2 assessment. Earlier work is mostly conceptual, introducing components of Ecological Systems Theory and underscoring its relevance and usefulness as a theoretical lens to L2 research. More recent publications, mainly adopting a qualitative research design, apply Ecological Systems Theory to examine sources of influence of L2 learning and teaching. Having said that, the majority of the reviewed studies demonstrate a fragmented application of Ecological Systems Theory, referring to specific notions of the theory such as “affordance” and “mutuality” rather than the philosophical underpinning of the theory (e.g., its eco-sociocultural view towards social phenomena, and its relationship with other sociocultural theories). Moreover, the central tenets of Ecological Systems Theory – interplay among (1) layers of contexts, and (2) contexts and people – are not captured in some of the reviewed studies. For example, some (e.g., Song & Ma, 2021*) focus on specific levels of contexts mentioned in Ecological Systems Theory rather than adopting a holistic view towards contexts, forfeiting the opportunity to examine the relationships among various contextual dimensions. Some (e.g., Hofstadler et al., 2021*), on the other hand, focus solely on contexts, neglecting the fact that people within the contexts are agentic beings who are not only influenced by the environments they are in but actively reshape the environments. With this timeline, we aim to introduce Ecological Systems Theory to the broad field of L2 research, demonstrating its usefulness as a theoretical framework. At the same time, we call for a more holistic and fine-grained understanding of the theory.

Sin Wang Chong (SFHEA) is Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Language Education at University of Edinburgh and is completing his second Ph.D. at University College London. Sin Wang is Associate Editor of two SSCI-indexed journals: Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching and Higher Education Research & Development. Sin Wang's research interests are in language and educational assessment, computer-assisted language learning, and research synthesis.

Talia Isaacs is Associate Professor of TESOL and Applied Linguistics and Programme Leader for MA TESOL In-Service at the IOE–UCL's Faculty of Education and Society, University College London. She has wide ranging research interests in applied linguistics, including second language speaking, language assessment, classroom-based research, and health communication. Methodological interests centre on mixed methods research and evidence synthesis. Talia is a current member of the TOEFL Committee of Examiners, serves on the Editorial Board of Language Testing, and was a core adviser to the OECD on questionnaire development for the PISA 2025 foreign language assessment.

Jim McKinley (SFHEA) is Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics and TESOL at University College London. He has taught in higher education in the UK, Japan, Australia, and Uganda, as well as US schools. His research targets implications of globalisation for L2 writing, language education, and higher education studies, particularly the teaching-research nexus. Jim is co-author and co-editor of several books on research methods in applied linguistics. He is an Editor-in-Chief of the journal System, and Co-Editor of the Cambridge Elements series Language Teaching (Cambridge University Press).