1. Introduction

As Porte & Richards (Reference Porte and Richards2012) suggest, replication is a tall order in experimental research, let alone in qualitative research. Furthermore, as these authors go on to point out, when we talk about replication, it is important to distinguish among exact (or literal) replication, approximate replication, and conceptual replication, in which different research methods are used to replicate previous findings. The advantage of this latter form of replication is that if the original results are confirmed, this enhances the likelihood that the results are not artifacts of the research design originally used.

So, can qualitative research be replicated (in any of the three senses sketched out above)? The standard reaction to this question is often a resounding ‘No!’ (see, for example, the classic paper by LeCompte & Goetz Reference LeCompte and Goetz1982, and the more recent piece by Casanave Reference Casanave2012). There are good ontological and epistemological reasons for this position, which I describe in more detail in the next section. However, what I will call comparative re-production research—that is, the empirical study of qualitative phenomena that occur in one context, which are then shown also to obtain in another—is a well-attested practice, even in ethnomethodological conversation analysis (CA).

At first blush, this fact may seem quite surprising, as CA is mostly skeptical about the value of quantification (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1993; however, for an opposite point of view, see Heritage Reference Heritage1999; Heritage et al. Reference Heritage, Robinson, Elliott, Beckett and Wilkes2007). Nonetheless, it is quite easy to find excellent examples of even the most stringent kind of replication research (i.e., exact replication) in CA. The classic example of such research is Moerman's (Reference Moerman1977) a priori comparative study of the preference for self-repair in Tai.Footnote 1 This paper not only re-produces (in the sense of intentionally producing X again in another interactional context, not in the sense of copying) the same preference displayed by English speakers in the original classic study by Schegloff, Jefferson & Sacks (Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977), but also makes clear that the purpose of this study is to address wider issues of the cross-linguistic generality of this preference among the world's languages.

I have emphasized the word generality because it obviously has to do with something that is similar to, but is also nonetheless ontologically and epistemologically different from, the concepts of generalizability and universality in experimental research. I discuss these issues in more detail in the next section. But for the moment, let me just gloss the question ‘is practice X a general phenomenon?’ as equivalent to the question ‘is practice X qualitatively organized in the same way across different languages and/or professional contexts?’

At this early point in the paper, I am conscious that I am already running the risk of simultaneously alienating qualitative colleagues who may bristle at the idea of doing research which could (incorrectly, I believe) be accused of mimicking experimental research and (further?) puzzling quantitative colleagues about what it is exactly that qualitative researchers do. So, to be clear: first, I hope to persuade skeptical qualitative colleagues that the kind(s) of research that I am proposing here—which include reference studies, approximate, conceptual, and (rather more rarely, perhaps) exact replications—is worth doing. Second, I want to show quantitative colleagues how such research is done and what it looks like. And third, I want to argue (to both qualitative and quantitative researchers) that issues of universality/generality are of common, fundamental interest to researchers of all ontological and epistemological persuasions.

Another short digression before I continue with the rest of the paper is now also in order. The present paper differs from the other publications in this series in that the other papers (all of which are experimental) review existing studies with a view to replicating them. However, in my view, comparative re-production research (particularly exact re-productions such as Moerman Reference Moerman1977) on the qualitative generality of particular practices in second/foreign language classroom research (S/FLCR) is essentially non-existent.

Now, it may be argued that this is too strong a statement. And indeed, this is precisely the line taken by an anonymous reviewer, who says: ‘I think this is an overstatement. If you take a practice such as repair in L2 classrooms, there have been many published CA studies which have examined repair practices in a particular context and compared what they found to other studies in other contexts. From a discourse analysis perspective, there are many studies from around the world showing the initiation-response-evaluation (IRE)/initiation-response feedback (IRF) pattern in L2 classrooms. I agree that such studies don't badge themselves as comparative re-production research, but you do read lots of claims about the generality/ubiquitousness of repair practices or IRE/IRF.’

My answer is that the key issue is whether such studies are intended to re-produce previous findings. In other words, comparative re-production research is distinct from primary empirical research that generally situates itself within a particular tradition or set of empirical findings and retrospectively uncovers cross-linguistic or other commonalities. The former specifically sets out a priori to find out how general specific practices may be on the basis of findings from a previous study. And that is why I claim that the field of S/FLCR would be methodologically and substantively enriched by research that was modeled on the comparison between Schegloff et al. (Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977) and Moerman (Reference Moerman1977).

Now, two papers that could form the basis for one strand of future comparative re-production research do exist. These are Markee (Reference Markee1995) and Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004), both of which: (1) focus on S/FLCR; and (2) use the tools of CA to investigate how a particular practice—namely, how teachers answer students’ questions during small group work—is done on a moment-by-moment basis in English as a second language (ESL) and Japanese as a foreign language (JFL) classrooms. However, there are at least three important reasons to go beyond these papers. First, strictly speaking, the second study is not a re-production study (whether we conceptualize such studies in approximate, exact or conceptual terms). It is a follow-up study, which, although it takes up the most important result of the original study, discusses several other practices that were not part of the first paper. Second, the comparative results of these two papers were inconclusive: the most important practice that I found in my paper was rare in Ohta & Nakaone's data, while another practice that was rare in my data occurred massively in theirs. Conversely, the most important practice that Ohta & Nakaone found in their paper was rare in my study, while the most important practice that occurred in their data occurred only once in mine. These are by no means uninteresting results. However, from the perspective of establishing the possible generality of the practices reviewed in the present paper, my paper and the subsequent Ohta & Nakaone study surely constitute a co-beginning, not the end of a comparative re-production research program on these issues. And third, as we will see shortly, unlike experimental research, which is quite unified in its methodological techniques, qualitative research is in fact a cover term for a number of often disparate methodologies. Thus, although I personally favor the use of CA for my own work, the comparative re-production S/FLCR program I am advocating here would be greatly enriched by studies that adopt other qualitative perspectives, such as (critical) ethnography or case study research (among many other possibilities).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, I briefly consider the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of replication research within the experimental research paradigm and then consider how CA research differs from experimental research. At the same time, I argue that a rapprochement between such different epistemologies is nonetheless not only potentially possible but also desirable. In Section 3, I compare the results obtained by Markee (Reference Markee1995) and Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004). And in Section 4, I first reflect on the kinds of generality statements that can be made in comparative re-production S/FLCR and then identify three topics that would lend themselves to such a methodology. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Background information: The ontology and epistemology of replication

The field of second language acquisition (SLA) studies has seen more than its fair share of epistemological warfare in the last 15–20 years (see, for example, the symposia in The Modern Language Journal based around Firth & Wagner Reference Firth and Wagner1997, Reference Firth and Wagner2007). However, I hope that the present paper transcends the largely polemical dimensions of earlier discourse surrounding the establishment of CA in SLA studies. In this spirit, I assume that (for good or for ill) CA in SLA studies is here to stay, and that I do not need to make the case for the legitimacy of this kind of research in 21st century applied linguistics. Let us therefore move on to consider where the idea of replication studies comes from.

Whole books have been written on this subject, the most recent (and most pertinent) of which for our purposes is Porte (Reference Porte2012).Footnote 2 Very briefly, and at the risk of brutally condensing many complex issues, experimental researchers start out by assuming that verifiable truths about the phenomena that they are interested in may be discovered, explained and generalized by studying these phenomena under carefully controlled laboratory conditions (see Hatch & Lazaraton Reference Hatch and Lazaraton1991 and Chalhoub, Chapelle & Duff Reference Chalhoub, Chapelle and Duff2006 for further discussion). More specifically, the research process typically starts with the development of predictive research questions and hypotheses that are derived from pre-existing theory. Aggregate data gathered in the laboratory are then manipulated using appropriate statistical techniques to determine whether the hypotheses are supported or not according to pre-determined levels of mathematical probability. Typically, the most valued results are those that reach statistical significance. Epistemologically, these results are held to explain a particular part of the phenomenon under study and to be generalizable from the sample to the wider population as a whole. However, hypotheses that are not supported are also useful, particularly in terms of fine-tuning the scope of underlying theory and the design of future empirical research. As studies on the phenomenon build up over time, a theoretically driven and empirically validated consensus eventually emerges regarding the phenomenon under study (say, the causal relationships between interaction and acquisition in the Interaction Hypothesis: see Long Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996). Replication studies (and by extension, meta studies Footnote 3 : see, for example, Norris & Ortega Reference Norris and Ortega2002, Reference Norris and Ortega2006) play a key role in the emergence of this consensus, in that such studies enable us to get ever more detailed pictures of what a phenomenon consists of, and why it behaves in the way(s) it does.

In qualitative research, a rather different set of assumptions governs the research enterprise. As a general observation, we should note that, unlike experimental research, qualitative research has many different manifestations (for an overview of these issues, see Chapelle & Duff Reference Chapelle and Duff2003; Richards Reference Richards2003; Merriam Reference Merriam2009; Stake Reference Stake2010; Cresswell Reference Cresswell2013) Here, I concentrate on how CA in particular is done. First, from an ontological and epistemological perspective, CA begins with the assumption that all knowledge about a phenomenon must be grounded in the local details of actually occurring, natural conversation, not from a priori theory. Thus, in contrast with experimental research, knowledge construction involves: (1) adopting an emic ( = participant oriented), not an etic ( = researcher oriented) point of view; (2) gathering naturally occurring data in everyday rather than laboratory contexts; (3) providing these data (that is, excerpts from the original recordings and accompanying transcripts) to readers for inspection so that readers can independently evaluate the authors’ analyses on the basis of the original data; and (4) interpreting these data to show how a particular practice (for present purposes, the ways in which teachers answer students’ questions during small group work) is observably organized as a series of inter-related sequential actions that occur at that particular moment in that particular conversation (Schegloff et al. Reference Schegloff, Koshik, Jacoby and Olsher2002).

At first sight, the ontology and epistemology of CA are quite different from that of experimental research. Most importantly, CA researchers seek to understand, not explain, phenomena. The research process begins with recording and transcribing naturally occurring talk, typically produced by dyads or small groups of participants, from which interesting phenomena are allowed to emerge for subsequent analysis. In other words, CA researchers do not use a priori theories, research questions or hypotheses to organize their research, at least not initially. So, for instance, when I first gathered the classroom data from which the results obtained in Markee (Reference Markee1995) were extracted, I let the research questions emerge from the data, in that I did not have any preconceived ideas about the specific phenomena that would prove to be of interest in the database. However, once such a phenomenon has been identified and documented at a particular level of abstraction, it is then legitimate for other researchers to look for the same phenomenon in their data. See Jefferson (Reference Jefferson1983, Reference Jefferson2002) for further exemplifications of this approach.

Recordings constitute the primary data for analysis, and publicly displayed transcripts (based on the kinds of fine grained transcription conventions found in Jefferson Reference Jefferson, Atkinson and Heritage1984), not statistics, constitute the discursive departure point for CA argumentation and analysis. More specifically, conversation analyses focus on the micro details of emerging talk in real time (for example, how participants take turns, repair various troubles in talk, or build spates of talk into socially organized sequences of interaction; see Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974; Schegloff et al. Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977, Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007).

As if these crucial theoretical and methodological differences between experimental research and CA were not enough, there is also the eminently practical point that there is (at least initially) no point in trying to gather CA data that address a priori research questions, since the practice that is potentially of interest may never even occur in a particular recording. Thus, it is easy to see why the concept of replication, which is so intimately tied to explanation and generalizability in the experimental paradigm, might be alien to CA researchers in particular, and to qualitative researchers more generally.

How can such major differences be reconciled, if at all? The first thing to recognize is that (as I demonstrated in the introduction to this paper) qualitative and quantitative researchers in fact often actually end up doing roughly similar things, although, following Guba (Reference Guba1981) and Guba & Lincoln (Reference Guba and Lincoln1981, Reference Guba and Lincoln1982, Reference Guba and Lincoln1989), it is probably prudent to call these related activities by different names in order to preserve the underlying ontologies and epistemologies of different research paradigms (though see Morse et al. Reference Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson and Spiers2002 for a contrary perspective). So, for example, I have proposed the term ‘comparative re-production research’ (in the sense of research whose fundamental results can intentionally be produced again in other interactional contexts, not in the sense of research whose results can be copied) as a qualitative alternative to the experimental term ‘replication research’. My rationale for doing this is that the principal goal of qualitative research is to understand, not explain phenomena. For similar reasons, I have borrowed Moerman's term generality as an alternative to generalizability, because CA focuses on how particular actions are done as qualitative achievements in real time, and not, as happens in experimental research, on why things happen in terms of a priori cause and effect relationships. Second, as demonstrated by Bachman (Reference Bachman, Chalhoub, Chapelle and Duff2006; see, in particular, pages 197–198), from a philosophy of science perspective, ontological and epistemological issues in applied linguistics are not nearly as black and white as my all too brief summary above might imply. At abstract levels of conceptualization, such differences frequently become much less prominent than they at first seem. And finally, if, as has actually been demonstrated in CA over a period of some 30 years, we find that certain practices are robustly instantiated in many different languages, cultures and/or professional contexts over time, it is hard in the end to escape the conclusion that such practices are massively applicable to many different conversational contexts (for a general discussion of context in CA, see Heritage Reference Heritage, Roger and Bull1989). Notice also that by invoking the concept of applicability or prototypicality, I am avoiding using the word universal, which, to my mind, is loaded with excessive experimental baggage. The consequences of this distinction are illustrated in more detail in my discussions of Fragment 4 later on in this paper).

More specifically, for experimental researchers, the goal of making universal generalizations is an a priori theoretical priority, while for qualitative (especially CA) writers, general statements that are applicable to other context-free examples of talk-in-interaction are cumulative by-products of empirical research (see Hammersley Reference Hammersley1992 about the place and function of theory in qualitative research; and Jefferson Reference Jefferson1983, Reference Jefferson2002, and Markee Reference Markee2008 about the same issue in CA research, respectively). It is within this broad comparative re-production perspective on the organization of talk-in-interaction that I ground the discussion of the target papers by Markee (Reference Markee1995) and Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004) that now follows.

3. The original studies

In Markee (Reference Markee1995), I studied what happened when students who were working in small groups during task-based instruction asked their teachers questions, typically about vocabulary they did not understand. The data for this particular pedagogical practice came from classes taught by teaching assistants in the ESL service courses at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, whom I recorded in 1990. The analyses were based on naturally occurring classroom talk produced by three teachers and their students in regularly scheduled university classes that lasted 50 minutes each. All three teachers were experienced ESL instructors, and all the students were mid- to late-intermediate students (in the sense that they had obtained a score of 550 on the paper-based TOEFL test, which the university used as a minimum admission requirement for international students).

The central finding in my paper was that teachers preferred (in the technical CA sense of this word) using what I called counter question (CQ) sequences in the original paper. CQ sequences are systematic modifications of teacher-fronted classroom talk. Following McHoul (Reference McHoul1978), teacher-fronted classrooms are prototypically organized in terms of recursive question-answer-comment (QAC) sequences (also known as initiation-response-evaluation/feedback or IRE/IRF sequences; see Mehan Reference Mehan1979, and Sinclair & Coulthard Reference Sinclair and Coulthard1975, respectively). More specifically, teachers ask students questions in first turn. In second turn, students must give teachers answers. And in third turn, teachers provide evaluative comments that evaluate the adequacy of students’ responses. These third turns either close a sequence, or serve as springboards for further recursive QAC sequences. Thus, to summarize who owns what kinds of turns in this speech exchange system, the discursive sequence organization of teacher-fronted classroom talk may be graphically represented as in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The ownership of turns and sequential structure in teacher-fronted talk

In the modified speech exchange system that I found in my data, when students asked teachers to join their groups in order to get help with understanding unknown language, instructors typically preferred to insert a CQ turn into these QAC sequences, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The ownership of turns and sequential structure of student-initiated questions during small group talk

Let me now provide three empirical examples of CQ sequences from the original paper (all the original transcripts have been revised). Notice also that in this paper, I focus only on the insights that were subsequently picked up by Ohta & Nakaone Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004). In each of these fragments, the instructor was a different individual, who was teaching different students, who were members of different classes.

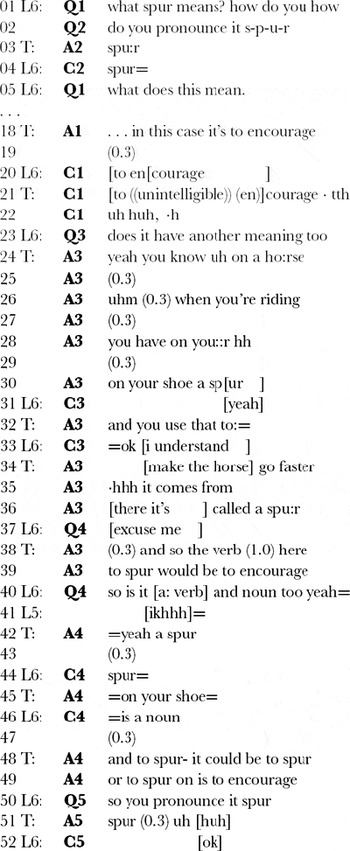

Fragment 1

The four components of the CQ sequential structure outlined in Figure 2 emerge as follows in this fragment. In lines 01 and 03, L7 formulates the initial question. In line 02, T acknowledges the question and does a CQ turn in line 04. This response effectively selects a speaker other than L7 to start speaking in next turn. L8 duly self-selects as next speaker in line 05 and goes on to produce an answer to T's CQ turn through line 08. In line 09, L12 adds his own suggestion, thus collaboratively expanding L8's answer. And in line 10, T closes the sequence by making an evaluative comment on the adequacy of the preceding answers.

Fragment 2

In this second fragment, we can see another instructor orienting to the same CQ practice. More specifically, L10 poses the question about the meaning of the word coral in line 01. In lines 03–06 (which have been omitted from the present version of the transcript), T does some preliminary work finding where this word occurs in L10's text, and then (as in Fragment 2) redistributes the question to the other group members with a CQ turn in lines 07–08. This action prompts L9 to begin providing an answer in lines 09–10, on which T then comments favorably in lines 11 and 13.

Fragment 3

In this last fragment, we have another example of the same CQ sequential structure. More specifically, in lines 01–10, L6 asks T to explain what the phrase ‘We cannot get by Auschwitz’ means.Footnote 4 T then does a CQ turn at line 11, and in lines 13–15, L6 self-selects as continuing speaker and provides a candidate answer to this CQ. Finally, in line 16, T says, ‘does it mean that?’ which: (1) assesses L6's answer as inadequate; and (2) simultaneously invites another learner to take over the next turn. I return to the significance of the seemingly minor difference in speaker selection behavior that occurs in lines 13–15 in Section 4 of this paper.

Why did these ESL instructors prefer such an organization? Figure 3 shows a potential consequence of teachers answering student questions directly in next turn:

Figure 3 The trajectory of student-initiated QAC sequences during small group talk

Fragment 4 (which is the only example of an instructor answering a student's questions directly that I found in my database) illustrates how this trajectory ran off in my data:

Fragment 4

Figure 3 and Fragment 4 show that learners who initiate questions are in sequential position to do final commenting turns (see the five QAC sequences that are identified in the transcript, namely: Sequences 1 and 2, lines 1–22; Sequence 3, lines 23–32, + 33–36 + 38–39; Sequence 4, lines 36–49; and Sequence 5, lines 50–52). However, these sequences are characterized by considerable internal complexity. For example, Sequences 1 and 2 are inextricably intertwined. The boundaries of Sequence 3 are a matter of contention between L6 and T (who is the same instructor that we already met in Fragment 2): the sequence is over for L6 at line 32 but T continues with her answer through lines 36 and 38–39. Sequence 4 (which tellingly starts with L6 saying ‘excuse me’ in line 37 in overlap with T's turn in line 36), is first fully stated in line 40 and goes on until line 49. However, as with Sequence 3, the boundaries of this sequence are ill defined. For L6, the sequence is over in lines 44 and 46. But T continues with her answer through line 49. It is thus only Sequence 5 in lines 50–52 that has a clean QAC organization. I therefore concluded on the basis of these and other fragments that the reason why the instructors preferred the interactional trajectory shown in Figure 2 was that it allowed them to maintain moment-by-moment control over the local pedagogical agenda in their classrooms.

Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004) carried out their study at the University of Washington under the same kinds of general conditions described in the first paragraph of this section, with similar university participants. This study not only investigated JFL instructors’ answering practices but also analyzed the quality of student–student interactions in small groups, which was not part of the original paper by Markee (Reference Markee1995). As I have already indicated, this fact indicates that, strictly speaking, Ohta & Nakaone's piece is more of a follow up study rather than an approximate re-production study. Furthermore, Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004) found very few CQ sequences in their data, but they did find many instances of JFL teachers at the University of Washington using a direct answering practice (see discussion of Figure 3 and Fragment 4) in the interactional environment under study. Fragment 5 provides an empirical example of how this practice ran off in their data (Ohta & Nakaone Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004: 232–233).

Fragment 5

The preference (again, in the technical CA meaning of this word) for direct answers exhibited by these JFL teachers obviously provides an interesting counter-finding to the ESL teachers’ preference for CQs in the ESL classes at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. But it would be even more interesting to look at what happens at the specific pedagogical decision point identified in the original paper in a broad range of L2 classrooms in a broad range of institutional settings in other parts of the world. In this way, we would be able to get a clearer picture about which of these two practices found so far at two US universities is the most prototypical.

In this context, Ohta & Nakaone (Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004: 236) conclude that:

These results show the importance of studying second language interaction in the varying contexts in which it occurs. Contrasting the effects of different classroom practices may give insight into which strategies are more or less useful in enhancing the effectiveness of peer interactive tasks in second and foreign language classrooms.

More specifically, it is clear that there are different floor issues when it comes to the use of CQ and direct answer sequences in small group work, as opposed to what happens during teacher fronted interaction, respectively.Footnote 5 In the latter context, teachers’ next actions (typically CQs, at least in ESL classrooms) are relatively non-problematic, because teachers know what has happened in previous talk, so that what is known and what is not known is relatively public knowledge. In contrast, in small group work, the situation is much more complicated. Teachers do not know what has transpired during previous interaction in different groups. Thus, they do not know whether members of a group have already tried to resolve a particular issue before they are invited to join the group's conversation. Consequently, a class in which small group work occurs is to all intents and purposes no longer treatable as a single group. Therefore, we would need to look at class contexts and group contexts separately (but possibly also comparatively), and within each context, we might then be able to identify other factors that might explain important differences in behavior (such as the ‘teachers from different cultural backgrounds or who have experienced different training’ issue in the quotation from Ohta & Nakaone Reference Ohta and Nakaone2004: 236).

By extension, we also need to ask what kinds of insights are unlikely candidates for generality statements about the prototypicality of particular behaviors because these actions are intrinsically local artifacts of talk that occurs at a particular moment in a particular conversation. In order to understand this issue empirically, let us now return to the apparently minor difference in speaker selection that occurs in lines 13–15 in Fragment 3. While we can discern the by now familiar CQ structure that organizes the instructor's talk in this fragment, it is clear that much more is going on in Fragment 3 than in Fragments 1 and 2 in terms of the complexity of the actions that are being performed in this talk. More specifically, L6 observably orients to a complex, highly delicate, problem in Fragment 3. That is, in lines 1–10, he simultaneously tries to: (1) get the instructor to clarify the meaning of the problem phrase ‘We cannot get by Auschwitz’; (2) discreetly suggest that he is acting on behalf of somebody else; and (3) avoid making the person who does not understand the meaning of this phrase (L15) lose face by identifying her too explicitly.

How can we empirically demonstrate these orientations in L6's observable verbal behavior? In line 01, he first says: ‘there is a problem here’. He then immediately continues to say: ‘she doesn't under(h)stand and we don't understand what h what means exactly this why we cannot get by Au/shvi/tz’ in lines 01, 03, 05–06 and 10. Thus, L6 begins by using the vague pronoun she to refer to L15 in the last part of line 01. In line 03, the word ‘under(h)stand’ is marked by a laughter token, a perturbation which frequently occurs in the environment of an ongoing repair, and in line 05, L6 changes his attribution of who has the problem of not understanding the problem phrase by changing the referential pronoun ‘she’ to ‘we’. Independent confirming evidence for this analysis is also provided by L15, who overlaps L6's talk with a laughter token of her own in line 02, as does L7 in line 04. Thus, both these participants also recognize the delicacy of the work that L6 is undertaking as he is producing it.

This reformulation of who owns the problem of not understanding the phrase ‘We cannot get by Auschwitz’ is actually rather generous on L6's part, since prior empirical evidence in the transcript (not shown here) demonstrates beyond doubt that L6 actually does know what this phrase means. More specifically, we know this because L6 tries several times (correctly, but, it turns out, unsuccessfully) to explain to L15 the highly symbolic meaning of this phrase before he eventually decides to call T over to break what he (L6) judges to be a deadlock that only T can resolve. However, this action has a number of problematic consequences for both participants.

First, for T, what L6 is doing during this talk is opaque, because she was busy monitoring other groups when L6 was trying to explain what ‘We cannot get by Auschwitz’ means to L15. It is therefore unclear whether she orients to the various delicate actions that L6 performs in lines 1–10. Consequently, the way she subsequently responds in the talk that follows may lead to a breakdown in intersubjectivity (which is in fact what happens). As for L6, he ends up being sanctioned quite sharply by T in line 16, when she says: ‘does it mean that?’ very quickly and sharply.

Now, an interesting question that becomes relevant at this particular moment in this particular conversation is: ‘Why does T sanction L6?’ It seems that there are two interrelated reasons why T performs this action. The most important reason is that L6's behavior in lines 13–15 violates an interactional norm in this institutional speech exchange system, which we have already seen in operation in lines 5–9 and 9–10 in Fragments 1 and 2 respectively. More specifically, when instructors do CQ turns (see lines 04, 7–8 and 11 in Fragments 1, 2 and 3), this action prototypically redistributes the next turn to another speaker, who is thereby cast as a potentially more knowledgeable participant than the current speaker. Thus, when L6 self-selects as continuing speaker in lines 13–15 of Fragment 3, he is apparently violating a normative, behaviorally manifested expectation in this institutional speech exchange system that a different speaker from current speaker must start talking after a CQ turn. This largely explains T's negative assessment in the C turn in line 16. Note, however, that this behavior may also be partially explained in terms of what the phrasal verb ‘get by’ might mean at this particular moment in this particular interaction. As I suggested in Note 4, T observably orients to this phrase in subsequent talk not shown here as meaning not allowing Auschwitz to happen again. However, L6's response in lines 13–15 is consistent with an interpretation of this phrase as meaning that Nazi racial policies during World War II represented an insurmountable obstacle to German reunification in 1990.

Now, this analysis is important from a general CA methodological perspective, because L6's apparently deviant self-selection behavior in Fragment 3 actually serves to confirm the claim made on the basis of the talk in Fragments 1 and 2 that teachers’ CQ turns normatively redistribute next turn to a different speaker. However, it would obviously be foolish to expect that exactly the same kind of locally contingent details that are relevant in Fragment 3 would ever occur in any other conversation. Thus, a key issue in making generality (i.e., applicability) statements in qualitative S/FLCR is to pitch such statements at the right level of abstraction from the data. And this is extremely hard for qualitative researchers, because we love to get into the details of interaction.

4. What kinds of findings need to be re-produced in qualitative S/FLCR?

In the previous section, I have outlined how further CA work in SLA on a rather precise topic—which would hopefully be explicitly designed as exact, approximate, and/or conceptual re-productions of the original behavior—could potentially lead to some interesting general statements about the relative prototypicality of different pedagogical actions in second and foreign language classrooms.

Now, the findings I have reported here essentially focus on the phenomenon of sequence organization in L2 classrooms. A research program in this area that would lend itself well to such a treatment would be John Hellerman's longitudinal work on students’ participation in various sequential practices at different levels of proficiency (see Hellerman Reference Hellerman2007; Hellerman & Cole 2007). In addition, comparative re-production studies in S/FLCR that focus on the other two aspects of the CA trinity—that is, turn taking (McHoul Reference McHoul1978; Mehan Reference Mehan1979; Markee Reference Markee2000) and repair (McHoul 1990; Seedhouse Reference Seedhouse2004)—would obviously also fit rather well in a qualitative S/FLCR program.

Second, research on massively common pedagogical actions—such as how teachers do giving instructions (see Seedhouse Reference Seedhouse, Garton and Richards2008; Hellerman & Pekarek Doehler Reference Hellerman and Pekarek Doehler2010; Markee 2015)—is likely to be productive, because: (1) these actions occur in all classrooms all over the world; and (2) their very familiarity probably hides surprising interactional complexities. And finally, I would recommend that research which goes beyond the spoken word and includes phenomena such as eye gaze, gesture and other forms of embodiment (see Goodwin Reference Goodwin2013) would also be highly productive, as it is becoming increasingly clear that human beings do not just use words—they also simultaneously use their bodies and their surroundings to communicate and to learn from each other. This too is an under-researched topic in S/FLCR (though see Markee Reference Markee2008, Reference Markee2011; Mori 2004; Sert Reference Sert2013; Sert & Walsh Reference Sert and Walsh2012 for promising developments in this area), and I predict that such a topic would lend itself very well to a comparative re-production methodology.

5. Conclusions

I hope that this paper has gone some way toward persuading qualitative colleagues who might be skeptical about the kind(s) of research I am proposing here is actually worth doing. I also hope that I have given quantitative colleagues an indication of how CA research is done. And finally, I hope that that I have provided a compelling rationale for researchers of all ontological and epistemological persuasions to focus on what ultimately unites us rather than what divides us. Qualitative and quantitative researchers have different views about the place and function of theory. However, what we have in common is a commitment to sound empirical work. This common orientation provides a foundation for complementary work, such as Heritage et al.'s (2007) quantitative study that was possible only because of prior conversation analyses that reveal two different ways of asking the ‘same’ question.Footnote 6 My proposals for a program of comparative re-production research in CA inspired S/FLCR are thus also ultimately quite consistent with multi-methods extensions of qualitative work on how teachers and students accomplish language learning behavior.

Numa Markee is an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he teaches courses in applied linguistics. His main research interests are in ethnomethodological CA for SLA, discursive psychology, and classroom research. He has written single authored books on the management of curricular innovation and CA for SLA and has an edited book on classroom interaction in the works. In addition, he has numerous book chapters and papers in refereed journals such as The Modern Language Journal, Applied Linguistics, the Journal of Pragmatics and Language Learning.

Numa Markee

Associate Professor

Department of Linguistics

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

4080 Foreign Languages Building

707 S. Mathews

Urbana, IL 61801