Introduction

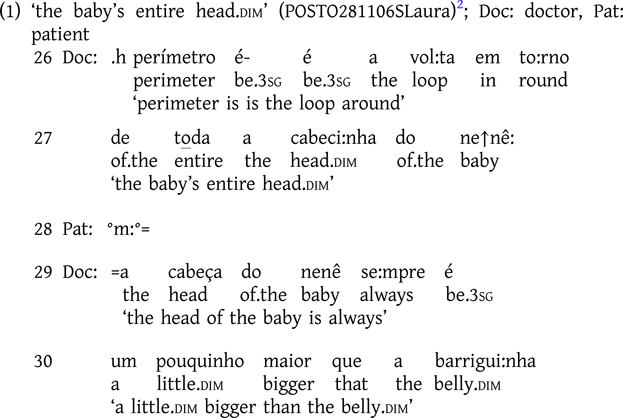

Consider the segment of interaction shown in (1) below, taken from a routine obstetric consultation in Brazil. A pregnant patient and herFootnote 1 doctor are discussing an ultrasound report which includes measurements of different parts of the fetus. They are considering the size of the baby's head.

When explaining that the ‘encephalic perimeter’ mentioned in the report refers to the circumference of a baby's head, the doctor uses the diminutivized form, cabecinha ‘little head’ (morphologically ‘head.dim’) (lines 26–27). Following this, he compares the size of a baby's head to that of the belly, using the base form cabeça ‘head’ (line 29). The doctor thereby produces both diminutivized and non-diminutivized (or base) forms of the same noun to the same addressee in close succession. Our research question is: how might the use of these two, almost juxtaposed, different formats be accounted for?

This is the empirical phenomenon that we explore in this article. We investigate moments where diminutive forms and base forms of a lexical item are used in close proximity. We compare the uses of diminutive forms with their base forms in their respective sequential environments in order to identify some of the primary functions of diminutive morphology in these clinical interactions. By taking action and the sequential progression of interaction as our analytic points of departure, our study exemplifies a novel comparative approach to diminutives, diminutivization, and the interactional relevance of morphological resources to social interaction—a profoundly data-driven approach which, we argue, pays off theoretically by inviting us to reconceptualize existing accounts in more specific or granular terms.

An interest in diminutives in the world's languages is of course not new. In the case of Portuguese, the language investigated here, the earliest written grammar—Fernão de Oliveira's Grammatica da Lingoagem Portuguesa (1536–Reference Oliveira2000)—included diminutive morphology alongside that of augmentatives and other suffixes. Contemporary researchers have continued to examine this feature of grammar in a wide range of different language systems, drawing from a diverse array of disciplinary perspectives. Despite generally being considered a canonically morphological topic, diminutives have been extensively investigated in semantics (e.g. Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996), phonology (e.g. Ferreira Reference Ferreira, Gess and Rubin2005), pragmatics (e.g. Sifianou Reference Sifianou1992; Schneider Reference Schneider and Schneider1999), and morphopragmatics (e.g. Dressler & Barbaresi Reference Dressler and Barbaresi1994). Moreover, diminutives and their uses have played a significant role in research addressing language and cultural socialization (e.g. Ochs, Pentecorvo, & Fasulo Reference Ochs, Pentecorvo and Fasulo1996; Savickienė & Dressler Reference Savickienė and Dressler2007), language and gender (e.g. Mendes Reference Mendes2014), and corpus linguistics (e.g. Turunen Reference Turunen2008).

The denotative semantics of diminutives is derived from the basic concept of dimensional ‘smallness’ (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996) relating to the prototypical dimensions of objects. However, diminutives are known to occur more frequently in contexts other than that of reducing the physical dimension of the referred entity, thereby inviting inquiry into other meanings and functions that such forms convey and index (Dressler & Barbaresi Reference Dressler and Barbaresi1994; Alves Reference Alves2006; Turunen Reference Turunen2008). From this morphopragmatic perspective, diminutives have been understood to operate in three main dimensions: the ‘referent’ dimension (i.e. what is being referred to), the ‘speaker and referred entity’ dimension (i.e. the type of relationship the speaker has to the referred entity), and the dimension of ‘speaker and recipient’ (the type of relationship held between speaker and addressee). Because diminutives may express, among other things, affect, proximity, attenuation, irony, and insignificance (Dressler & Barbaresi Reference Dressler and Barbaresi1994), they have been referred to as belonging to a class of morphology known as ‘evaluative morphology’, alongside augmentative and superlative suffixes (Grandi & Körtvélyessy Reference Grandi, Körtvélyessy, Grandi and Körtvélyessy2015; Costa & Minussi Reference Costa and Minussi2019).

Although pragmatic approaches have indeed been used to study diminutives, Raymond (Reference Raymond2022) notes that such research predominantly relies on single-utterance exemplars that are either invented or extracted from their original environments of occurrence. Data of that sort limits investigation in myriad ways, not the least of which is that the researcher is hindered by their own imagination (see Sacks Reference Sacks, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984). When working with naturally occurring, recorded social interaction, however, researchers are presented both with phenomena that could not have been imagined, and access to the particular sequential environments in which those phenomena occur (see Drew, Ostermann, & Raymond Reference Drew, Ostermann, Raymond, Robinson, Clift, Kendrick and Raymond2024). This is the approach taken in the present study.

In what follows, we begin by describing our dataset of Brazilian obstetric and gynecological consultations, and the endogenous comparative approach adopted in examining these data. We then draw attention to what has been argued in many languages (including Portuguese) to be the primary pragmatic function of diminutives in discourse—namely, ‘mitigation’. While we undoubtedly find support for this generic function in our data, we show that the notion can be further particularized in terms of the specific actions, within sequences of action, that diminutive formulations are implicated in and accomplice to. We offer an account of diminutive usage that has significant ‘empirical “bite”’ (Evans & Levinson Reference Evans and Levinson2009:475) in being tethered to the details of participants’ real-time contributions to interaction. In our final section, we discuss some of the implications of this analysis and suggest some potential avenues for future research.

Data and methods

This study draws upon data from a larger project, coordinated by Ostermann, which was designed to investigate how ‘humanizing’ national government policies and plans implemented in the early 2000s were translated into interactionally situated practices in women's health (Ostermann Reference Ostermann2021). The interactional corpus consists of 145 audio-recorded obstetric (N = 41) and gynecological (N = 104) consultations in Brazilian Portuguese, conducted by four physicians (three men, one woman) at a women's public healthcare clinic in Southern Brazil. All consultations were fully transcribed following the conversation-analytic (hereafter CA) conventions developed by Jefferson (Reference Jefferson and Lerner2004).

In Brazilian Portuguese, diminutives are formed using the suffix -(z)inh- —which can be morphologically specified for gender, -(z)inho (dim.m) and -(z)inha (dim.f), and number, -(z)inhos (dim.m.pl) and -(z)inhas (dim.f.pl)—attached to the stem of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and, in colloquial usage, also in pronouns and numerals. Some illustrative examples from the current dataset are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Brazilian Portuguese diminutivization.

Having identified all cases of diminutive use in the data (over 500), we approached their use, particularly by the doctors, from an endogenously comparative perspective (Drew, Ostermann, & Raymond Reference Drew, Ostermann, Raymond, Robinson, Clift, Kendrick and Raymond2024). Specifically, we scrutinized segments within the same interaction in which the same word (e.g. cabeça ‘head’) was used in its diminutive form and its base (or other, for example, augmentative) form, often in close succession, as we saw in extract (1). In this way, we hold constant the prototypical dimensions and variables canonically treated in diminutive research as motivating diminutive usage—that is, speaker, recipient, speaker-recipient relationship, and referent. Instead, we turn to the naturally occurring temporality and sequentiality of interaction (see e.g. Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007; Mushin & Pekarek-Doehler Reference Mushin and Doehler2021) to reveal the action environments to which participants recurrently attend in producing diminutive (and base) formulations in these medical consultations.

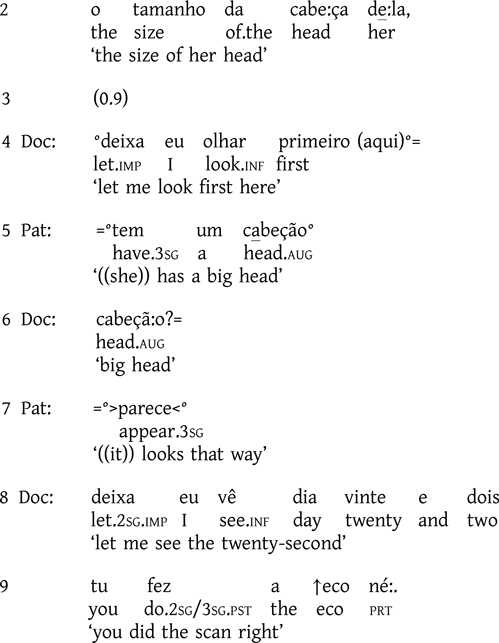

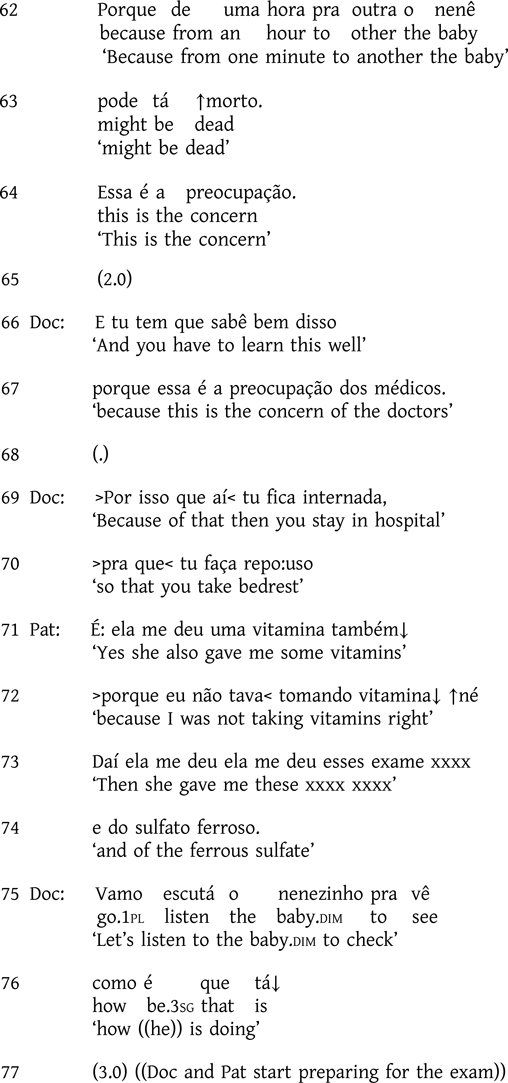

The affordances of this methodological approach can be illustrated by returning to our opening example, in which we saw a doctor use both the base form cabeça and the diminutive form cabecinha. Although it is difficult to discern the functions of these forms from just these turns in isolation, consideration of the broader sequential context in which they are produced gives analysts greater access to the particular actions implemented by the doctor. Extract (2) below occurs before extract (1); observe here how the patient launches the discussion about the baby's head as a ‘concern’, prompted by what she read in the ultrasound report.

When we consider the sequential environment that preceded extract (1), we can begin to uncover possible systematicities and analytic evidence absent in utterance-level inquiry. We see, for example, that the patient introduces the size of the baby's head as a concern; in her opinion, it seems too large (lines 1–2, 5)—an assessment to which the doctor orients as newsworthy and meriting further examination (lines 6, 8–9) (on clinicians’ management of patient's concerns, see e.g. Nishizaka Reference Nishizaka2011; Frezza & Ostermann Reference Frezza and Ostermann2021). While we reserve a more detailed analysis for the next section, we can note that the earlier sequence in extract (2) establishes the context in which the discussion shown in extract (1) occurred, in which both a diminutive and a base form were used.

This is what we mean by comparison in the ‘endogenous’ sense—that is, within the same interaction and sometimes even within the same sequence of talk. This methodology reveals sequential and action contexts in which diminutives are systematically and routinely produced; with those contexts thrown into relief, analysts are then able to return to the broader collection of diminutives to confirm whether such formulations are in any way recurrent in those positions, even in the absence of an adjacent base form. In what follows, we exemplify this methodological procedure, which allows us to respecify the well-known pragmatic function of ‘mitigation’ of diminutives. Note that while cases where the different forms for the same referent (in the strict sense of the term) are our primary focus in this report, our approach also allows us to explore instances in which there is or might be some maneuvering within the referential dimension from the participants’ perspective, as shown in a few of the cases reproduced here.

Diminutives in action, part 1: Unpacking ‘mitigation’

A primary and generic pragmatic function of diminutives—one widely attested across languages, including Portuguese (e.g. Alves Reference Alves2006; Turunen Reference Turunen2008; Bisol Reference Bisol2010; Costa & Minussi Reference Costa and Minussi2019)—is that of mitigation, typically conceptualized as in some way reducing the ‘force’ of the action in which the form is implicated. While this overarching function is clearly visible in the obstetric and gynecological consultation data that we consider here, such a broad-strokes account is underspecified in terms of the actual actions involved. That is, it leaves open the question as to where—within the ‘inescapable temporality of interaction’ (Raymond, Clift, & Heritage Reference Raymond, Clift and Heritage2021:722)—such ‘mitigation’ is deemed a relevant component of action by participants. How do interactants themselves mobilize this form of mitigation in the service of particular actions, in specific sequences of action? The methodological approach we adopt here reveals two particular action and sequential environments in which mitigation via diminutivization is regularly implicated in this setting: (i) to offer reassurance, and (ii) to attenuate intrusiveness. By drawing attention to these specific actions and where they occur, we offer an account of diminutivization and ‘mitigation’ in this context that is both more granular than that which has been posited in the literature thus far, and more firmly grounded in the evolving intersubjective perspectives of the participants themselves.

Let us briefly return to our initial extracts but examine them in the actual order in which they occur in the unfolding interaction. In extract (2), the patient presents her concern regarding the size of the baby's head with an inquiry about its normality, and an evaluation of its size, for which she uses the augmentative suffix -ão, cabeção ‘big head’ (lines 1–5).Footnote 3 In continuing the exchange (see extract (1)), the doctor reassures the patient regarding the normalcy of the baby's head. This reassurance is achieved through the use of a diminutivized form in referring to the perimeter of the baby's head, cabecinha ‘head.dim’ (line 27). In the wake of this reassuring action, in his subsequent turn the doctor uses the base form cabeça ‘head’ (line 29) to account for this reassurance: he delivers a generic comparative description (i.e. ‘always a little bigger’) between the size of a baby's head and its belly (diminutivized to indicate smallness). Thus, across this stretch of talk, we see a sequential, morphological transformation of the lexeme cabeça ‘head’, from the augmentative cabeção (by the patient) to express concern, to the diminutive cabecinha (by the doctor) to issue reassurance, to the base form cabeça (also by the doctor) as the medical reasoning for that reassurance is explained. In this way, ‘mitigation’ serves to offer reassurance in light of a patient's concern.

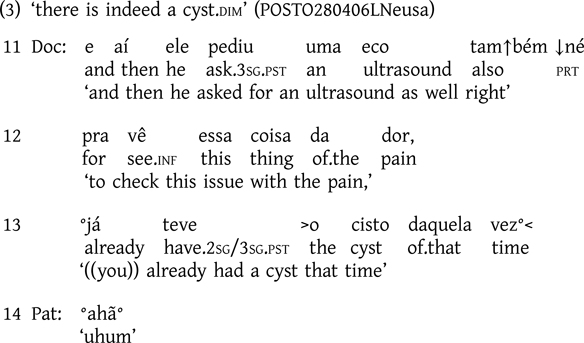

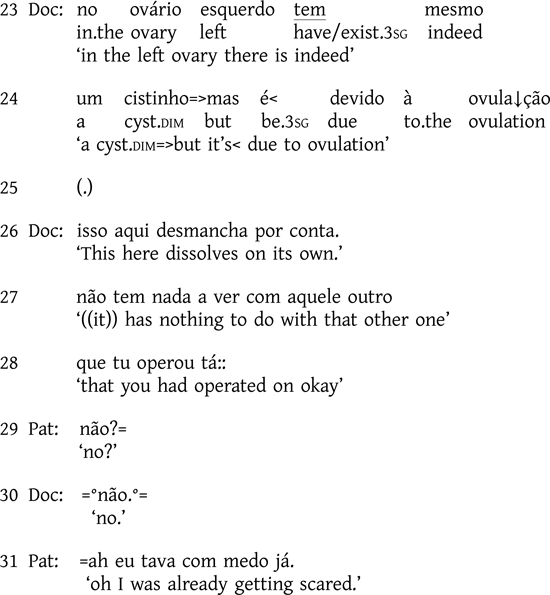

For a similar instance, consider extract (3) below. Immediately before the segment shown here, the patient reported having had part of an ovary surgically removed due to the development of cysts. She has brought with her to this appointment ultrasound results showing a recurrence of cysts. We join the interaction as the doctor begins engaging with the imaging reports.

((Omitted lines during which Doc examines the ultrasound report))

The doctor first refers to the earlier, surgically removed cyst with base format, cisto ‘cyst’ (line 13). After reviewing the report, he confirms that a new cyst has indeed developed, but he refers to the object with the diminutivized form, cistinho ‘cyst.dim’ (lines 23–24). This turn design not only delivers a diagnosis (i.e. that the patient does have a cyst) but also issues reassurance by qualifying the severity of that diagnosis. As seen in our prior examples, the doctor continues to account for this evaluation medically; he even employs a rush-through (Walker Reference Walker, Barth-Weingarten, Reber and Selting2010), circumventing possible speaker transition, in pursuing this adversative but-prefaced explanation (line 24). After a brief silence, he continues with the prognostic upshot of this explanation, namely that no surgery is necessary as this cyst differs from the patient's earlier ones (lines 26–28). Additional evidence of the relevance of issuing reassurance in the delivery of this diagnosis is shown in the subsequent expansion of this sequence—both in the patient's known-answer request for confirmation (line 29; Raymond & Stivers Reference Raymond and Stivers2016), as well as her on-record change-of-state ah (Heritage Reference Heritage, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984) now that she is no longer ‘scared’ (line 31).

The other principal sort of mitigation in our data is the use of diminutives to attenuate intrusiveness. In these obstetric and gynecological consultations, this intrusiveness is often physical, with the doctor physically manipulating the patient's body as well as using a range of specialized (and often uncomfortable) medical instruments. In extract (4) below, for instance, following a Pap smear test showing an alteration, the patient has scheduled this visit for a colposcopy—a procedure to examine the uterine cervix, vagina, and vulva for signs of (pre)cancerous tissue. Here, the doctor explains how the procedure works. Our focus is on lines 5 and 9, where reference is made to the apparatus that will be used.

The introduction of a device into the vaginal canal is not an innocuous action and might therefore be cause for some apprehension on the part of the patient. The doctor's use of diminutive morphology in first topicalizing the apparatus (aparelhinho ‘apparatus.dim’, line 5)—and in a turn describing specifically how the apparatus will be used (i.e. ‘put inside the vagina’)—displays an orientation to this reality by mitigating the intrusiveness of the object within the patient's body. Once this mitigating action is delivered and receipted (line 8), he subsequently uses the base form aparelho ‘apparatus’ to describe and account for the object's medical functionality (lines 9–10, 12).

While prior work has highlighted mitigation as an overarching pragmatic function of diminutive morphology (in Portuguese and beyond), by tightening our analytic lens to take social action and sequential context into consideration, we are able to respecify mitigation as a participants’ construct, demonstrating how participants themselves make mitigation interactionally relevant and procedurally consequential. In these obstetric and gynecological data, the diminutive's denotative semantics of ‘smallness’ is routinely implicated specifically in issuing reassurance, in turns that are responsive to concerns presented by the patient, and attenuating intrusiveness, in turns that are not responsive to a patient's first action, but instead orient to a current or future course of (manual) action that the doctor will engage in. Our approach thereby illustrates novel ways that mitigation, enacted through grammar, serves as a profoundly social resource, produced by and for co-interactants as they navigate social encounters in real time.

Diminutives in action, part 2: Pursuits and transitions

The endogenously comparative approach that we adopt here not only allows us to respecify the overarching pragmatic function of ‘mitigation’ in more specific, sequential detail than is achievable with utterance-level inquiry; it also allows us to identify other systematic uses of diminutives that may escape this generic categorization, at least initially. Such uses have thus far gone largely if not entirely unnoticed in the literature—perhaps because they are less intuitively ‘imaginable’ or ‘inventable’ (cf. Sacks Reference Sacks, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984)—and have therefore remained unexamined, with the result being an incomplete picture of the nuanced interactional work that diminutives are in fact implicated in. In this section, we draw attention to two further sequential and action environments in which diminutives are recurrently produced in these obstetric and gynecological data: (i) in pursuits, in response to patient resistance, and (ii) in transitions, as doctors bring one phase of the visit to a close and launch another. Crucially, these uses of diminutives are altogether undiscoverable without attending to the moment-by-moment sequential progression of interaction, and thus the approach we take here again further refines our conceptualization of the so-called ‘mitigating’ function(s) of diminutives in action.

Responding to patient resistance: Diminutives in pursuits

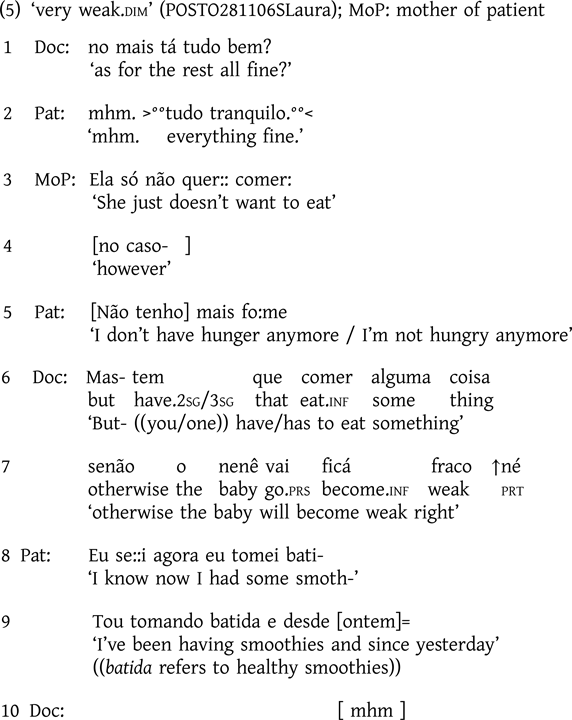

Consider extract (5), involving a young pregnant patient whose mother is present. The topic of discussion here, introduced by the mother (line 3), is the patient's eating habits. The doctor's first attempt at recommending and accounting for behavior change—Mas- tem que comer alguma coisa senão o nenê vai ficá fraco ↑né / ‘But- ((you/one)) have/has to eat something otherwise the baby will become weak right’ (lines 6–7)—is initially resisted by the patient (lines 8–9), in response to which the doctor continues by listing specific foods the patient should be eating (lines 14–19). When met with yet further resistance from the patient, citing fear of nausea (lines 20–21), the doctor re-issues the recommendation and accompanying account, this time employing diminutive morphology: ‘otherwise the baby becomes weak.dim’ (lines 22–23).

((a few lines omitted))

Recent research has highlighted two main activities in which patients enact resistance within medical consultations: diagnosis (e.g. Ijäs-Kallio, Ruusuvuori, & Peräkylä Reference Ijäs-Kallio, Ruusuvuori and Peräkylä2010; McCabe Reference McCabe2021) and, as we see in extract (5), recommendations (e.g. Kushida & Yamakawa Reference Shuya, Yamakawa, Lindholm, Stevanovic and Weiste2020; Ostermann Reference Ostermann2021). Patient resistance can be more active, including actions that postpone or halt an aligned response—for example, requests for further information, accounts, and repair initiations (Stivers Reference Stivers2005, Reference Stivers, Heritage and Maynard2006; Gill, Pomerantz, & Denvir Reference Gill, Pomerantz and Denvir2010); or it may be achieved more passively—for example, deviation to another topic and away from the initiated action, withholding acceptance, or agreeing only minimally (Koenig Reference Koenig2011; Ostermann Reference Ostermann2021). When encountering resistance, doctors respond in varying ways (see e.g. Stivers & McCabe Reference Stivers and McCabe2021)—ranging from adapting or even changing recommendations, to demonstrably not doing so and instead ‘doubling down’ to pursue acceptance of the original recommendation. It is the latter strategy that we see in extract (5), in which the doctor reissues the recommendation and its warning account, now selecting the diminutivized version of the same lexical item: …senão o nenê fica muito fraquinho ‘otherwise the baby becomes very weak.dim’ (lines 22–23). Cases such as this are clearly occupied with mitigation of a different sort than those we saw in the previous section. Here we find the diminutive implicated in a highly agentive pursuit of agreement—one that is produced in conjunction with additional features of turn design that are likewise ‘upgraded’ from the initial version in lines 6–7 (cf. Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984). Note also the shift from the earlier use of the future (vai ficar ‘will get’) to now using the present (fica ‘gets’), and the addition of the intensifier muito ‘very’. And indeed, the patient orients to the upgraded nature of this turn as a pursuit action by issuing a limited concession, namely that she ‘has been drinking plenty of water’ (lines 26–27) which the doctor agrees is ‘important’ (line 28).

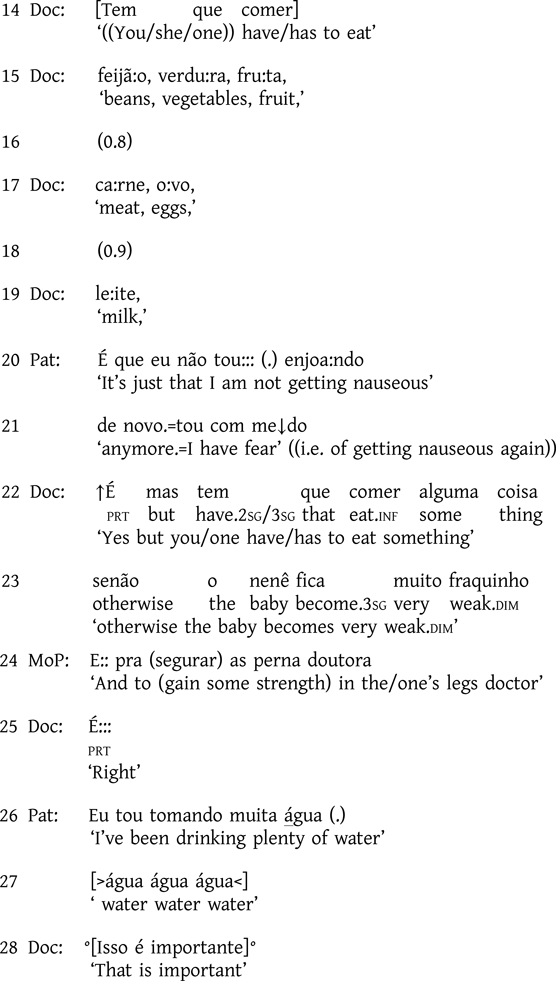

Extract (6) offers another instance of the use of the diminutive in a doctor's pursuit in the sequential context of patient resistance. The patient has presented with a type of benign cyst (‘Bhartolin's cysts’) that requires no treatment (data not shown); the extract begins after the doctor has delivered the diagnosis and indicated that no treatment is needed. As seen across the segment below, the patient resists this diagnosis and accompanying no-treatment recommendation—both more actively, by topicalizing other specific negative outcomes that the condition may cause (lines 1, 14), as well as more passively, by withholding response or responding only minimally to the doctor's medical explanation (lines 3, 6, 8, 18), which in turn prompts the doctor to continue (e.g. lines 4, 7, 11).

Following a series of long silences (lines 3, 6 and 18) at which points the patient does not respond, and her minimal (line 8) and skeptical (line 14) responses, the doctor pursues an explicit display of understanding from the patient, which she provides in line 20 with ‘okay, thank god’. The doctor, clearly unconvinced that this display is genuine, and after another silence (line 21), continues to describe the cyst with an even more innocuous and benign terms in pursuit of another, more genuine response from the patient. He compares the cyst to a wart—first using the base form, é como se fosse uma:: verruga na pe↓le ‘it's as if it were a wart on the skin’ (line 22), before articulating the upshot of that comparison using the diminutive form, verruguinha ‘wart.dim’ (line 24). This turn can also be said to be concerned with issuing reassurance, as described in the previous section, and thus these uses are not altogether mutually exclusive. Note, however, that the reassurance in this case is offered primarily as a response to the patient's continued resistance (cf. e.g. extract (3)), and in pursuit of acquiescence to the diagnosis and no-treatment recommendation that have been made. Continued orientation to this pursuit context is seen in the aftermath of this turn, as further explicit stance displays are issued, re-solicited, and reconfirmed (lines 26–28).

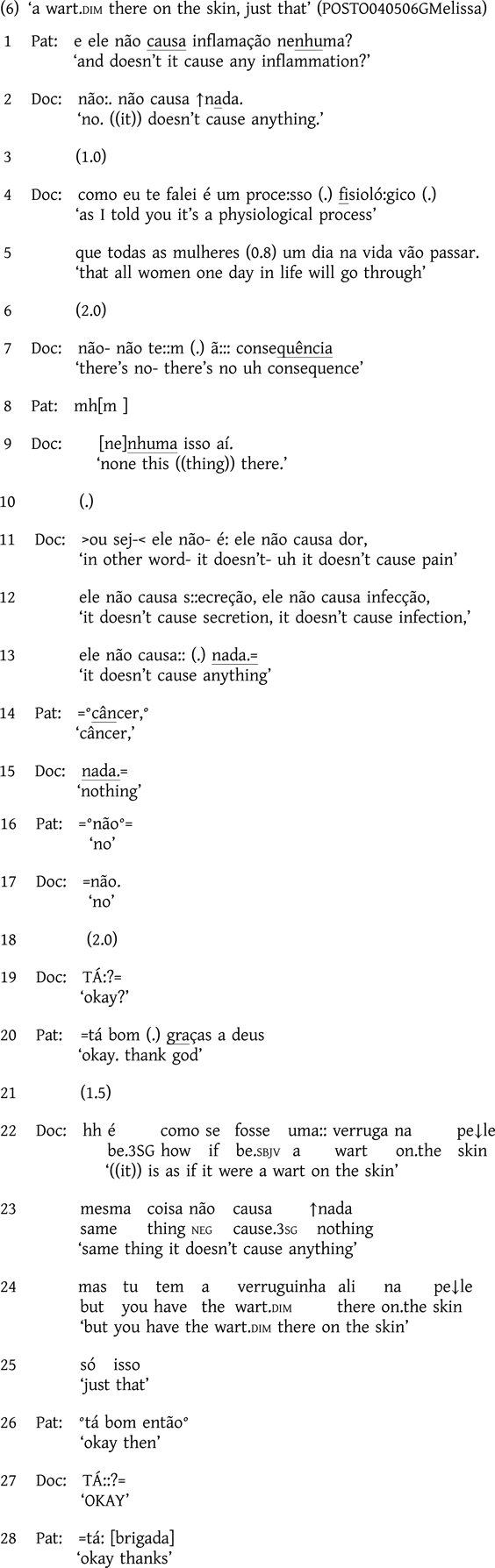

One additional example of patient resistance, and subsequent doctor pursuit, is found in extract (7) below. After the interactants have concluded the physical examination, the doctor delivers a treatment recommendation that will include two injections, one on each side of the patient (lines 1–5). As the doctor begins to write the prescription (line 6), the patient interdicts to ask tem que tomá as duas junto? ‘does one have to take the two together?’ (line 7), thereby resisting the proposed course of action or, at least, postponing acceptance. Following the doctor's repetitional confirmation in line 7 (Harjunpää & Ostermann Reference Harjunpää, Ostermann, Bolden, Heritage and Sorjonen2023), observe her shift to the diminutivized form ladinho ‘side.dim’ as she explains the particular way that both injections are administered together (line 9–11), which the patient finally acknowledges (line 12).

In this section we have shown that when patients resist doctors’ advice or their diagnoses or treatment recommendations, doctors routinely deploy diminutives as part of pursuit actions, combining this grammatical resource with other features of turn design that are demonstrably upgraded in various ways vis-à-vis alternative designs. In this way, doctors can pursue on-record acceptance of, or at least acquiescence to, their diagnoses and recommendations, and proceed to the next phase of the visit. We reserve consideration of how such an account further particularizes the notion of ‘mitigation’ for the discussion section, after a presentation of diminutives in activity or phase transitions, to which we now turn.

Diminutives in activity or phase transitions

The other sequential environment in which we systematically find diminutives in our obstetric and gynecological data is in transitions from one phase or activity of the medical consultation to another. Such moments have been shown in prior research to be the site of important interactional work within the visit, as patients collaboratively negotiate these transitions—for example, moving from history-taking to a physical examination of the patient, or from treatment recommendation to closure of the visit (see e.g. Robinson & Stivers Reference Robinson and Stivers2001; Robinson Reference Robinson2003; Ostermann & Harjunpää Reference Ostermann, Harjunpää, Betz, Deppermann, Mondada and Sorjonen2021). Adopting our endogenously comparative approach, we explore the use of diminutives in turns dedicated to the management of these phrase/activity transitions.

Extract (8) occurs in an obstetric consultation with a high-risk pregnant patient who has a low placenta level and fetal weight, continues to smoke, and may have syphilis. The segment follows a sequence in which the doctor has warned and admonished the patient after learning that the patient had discharged herself from the hospital when ordered bed rest and had missed a rescheduled clinical visit. The doctor's initial references to the patient's baby make use of the base form nenê ‘baby’ (lines 13–17, 62–64) in addressing the high-risk level of the patient's pregnancy (i.e. risk of fetal death), which the patient passively resists through silence and minimal response (lines 9, 14, 16, 65). When the patient responds more explicitly, she does so defensively, asserting that she has been taking the vitamins and supplements that she was prescribed (lines 71–74). In the context of this assertion by the patient, which disattends the doctor's extended recommendation of bed rest, the doctor proposes to transition away from this discussion of risk and into a physical examination, shifting to the diminutivized form nenezinho ‘baby.dim’ in doing so (lines 75–76).

((Lines omitted, during which Doc explains severity of the case,

urging Pat to follow the recommendations.))

In this case we see an extended pursuit by the doctor in the context of patient resistance, similar to the kind of sequential environment we illustrated in the previous section. Here, however, the diminutive is not implicated in the pursuit itself, but rather in its abandonment. That is, the action in which the diminutive occurs does not continue to pursue acquiescence or agreement with the prior line of action (i.e. the patient's responsibility in causing risk to the baby), but rather demonstrably transitions to a distinct phase of the visit: the physical examination. Following line 76, both doctor and patient begin to move into position for the examination, thereby showing successful uptake of the transition action.

The following is another case that illustrates the transition from the greeting and opening phases to the proposal to complete a new patient intake form.

The patient begins by announcing that she has brought test results conducted elsewhere (lines 6–8). Before looking at those results, the doctor checks the patient's status (i.e. whether or not she is a new patient), which determines what will be done next, in this case, to start a new patient's file. To announce this activity and transition into it, the doctor uses the diminutive form fichinha ‘file.dim’ (line 15). Note that, in the context of the patient's subsequent open-class initiation of repair (Drew Reference Drew1997) (line 17), the doctor reissues the turn, but this time without the connector então ‘then’ and with the non-diminutivized base form ficha ‘file’ (line 19), as this turn is now occurring within a repair sequence as opposed to proposing a transition (on which, see Jefferson Reference Jefferson1978; Schegloff Reference Schegloff2004).

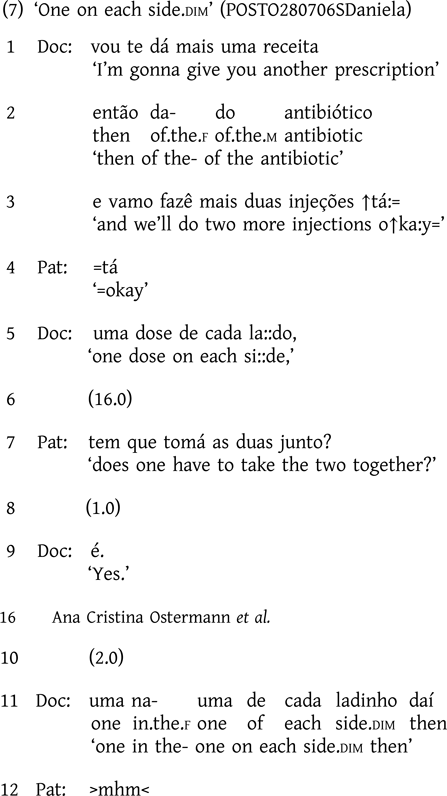

Extract (10) is taken from the same gynecological consultation seen above in extract (6), and illustrates a similar sequential progression to that which we just saw in (9). The action and sequential environment examined here—that is, launching instructions (sometimes a series of them) on how to arrange the body for the start of the physical examination—is one in which diminutives are recurrently deployed in this dataset. Extract (10) begins with fifty-eight seconds of silence during which the doctor prepares the instruments he will be using, and the patient accommodates herself on the examination table. Note the doctor's initial use of the diminutive form perninha ‘leg.dim’ to launch his instructions (line 12), which are to place one leg on each side of a metal stand to position the patient's body for examination. In the context of a request for clarification from the patient (line 13), the doctor shifts to using the base form pernas ‘legs’ when issuing subsequent directives outside of the sequential environment of transition (lines 14, 17).

Inserted activities.

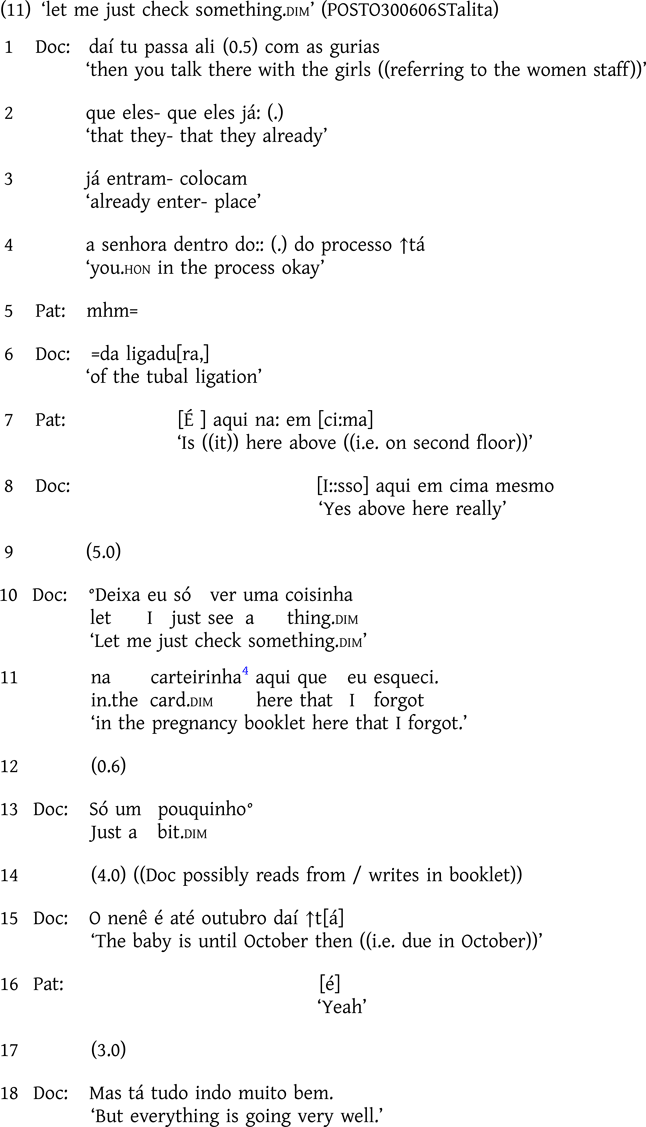

A subset of our cases of diminutives in transitions involve inserted activities, in which the doctor halts the expected progression of the consultation—something like ‘breaking the order’—to detour to new, emerging business. Extract (11) illustrates this; the segment occurs toward the end of the consultation when the doctor has already handed the patient the referrals to initiate the sterilization process of tubal ligation.

Having instructed the patient where to take the paperwork (lines 1–8), a pre-closing device in medical consultations (West Reference West, Heritage and Maynard2006), the doctor suspends the transition into the closing phase to insert something he has just remembered he should do: deixa eu só ver uma coisinha na carteirinha aqui que eu esqueci ‘let me just check something.dim in the pregnancy booklet here that I forgot’ (lines 10–11). ‘Something’ (coisinha) is produced in the diminutive form, thereby attenuating his halting the normative progression of the consultation in order to engage in another activity. Note also the use of só ‘just’ (cf. Marrese Reference Marrese2022), with both this device and diminutivization reissued in the subsequent elided version of the transition turn: só um pouquinho ‘just a bit.dim’ (line 13).

A similar situation happens in extract (12) below, this time at the beginning of the consultation.

((Pat continues presenting the reason for the visit))

After a greeting exchange and what seems to have been the patient's (self) initiation of the problem presentation (line 4, but inaudible), the doctor halts the progression of the consultation to finish the task with which she was engaged when the patient entered (lines 5–7). To do so, as in extract (11), she uses a diminutive form coisinha ‘something.dim’, and ‘just’, indicating a brief, temporary suspension of the interaction with the patient. The doctor thereby achieves a form of mitigation that addresses having to halt the progression of the consultation to handle something else first.

Asking the patient's age.

Doctors in our dataset regularly ask patients both for their current age and their age when some medical event occurred, which in Portuguese typically takes the form of asking ‘how many years’ the patient has/had. This question offered an interesting case study for our analysis, as it allowed us to systematize yet another dimension of comparability across cases. In focusing on this particular question—including its form and its sequential position—we were able to hold constant other features of turn design in these cases, and further interrogate how (non)diminutive morphology intersects with the sequential progression of the visit.

First consider extract (13), in which an elderly patient (either sixty-eight or seventy-eight-years-old—unclear) has come for a general check-up. In this case, the doctor uses the diminutive form in asking the patient's age, diminutivizing ‘years’ in ‘with how many years are you’ (line 3).

((omitted lines, Doc asks birth place))

Although it may be tempting to point to external categorizations (i.e. the patient's advanced age) and notions of ‘elderspeak’ (see e.g. Shaw & Gordon Reference Shaw and Gordon2021) to account for the doctor's use of the diminutive in line 3, such a categorial explanation lacks empirical support (both in individual cases, as well as across the dataset), and moreover fails to specify why this particular turn and action would include ‘elderspeak’ when others do not. In the continuation of this example, for instance, to ask the patient's age when her menstruation ceased, the doctor uses the base form of ‘years’ instead (line 12). The primary difference between these turns and their designs, we argue, is their sequential position: the first (diminutivized) form is produced in conjunction with transitioning to a new activity (i.e. launching history-taking to start a new patient file), whereas the later (non-diminutivized) form occurs well within that ongoing activity, and thus diminutivization is not deemed interactionally relevant. It bears mention as well that these two age questions differ in their second-person pronominal choices—namely with a shift from a senhora (V-form) in line 3, to tu (T-form) in line 12 (on which, see Ostermann Reference Ostermann2003; Raymond Reference Raymond2016)—thereby further supporting our claim that the category of ‘age’ cannot be the overriding explanatory variable for the linguistic conduct here.

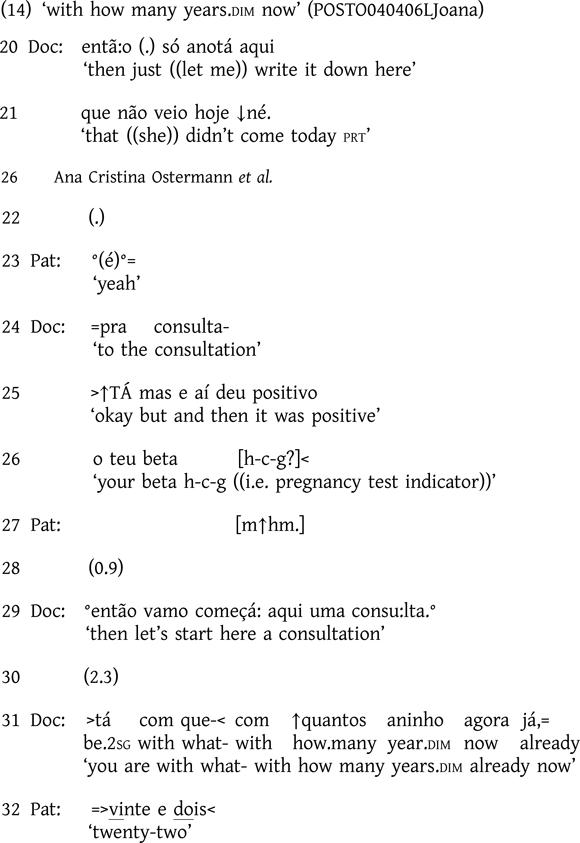

The use of diminutives in transitioning to begin filling out the ‘patient file’, which starts with information about the patient's age, is recurrent in our data. This is the case even when visits begin differently, such as in extract (14) below, when a twenty-two-year-old patient enters the room already announcing that her pregnancy test came back positive. This results in a delayed exchange of greetings and the patient launching a story regarding her pregnancy test (data not shown here). In the segment below, the doctor orients to such a ‘crooked’ start (and that the patient ‘jumped in the queue’) by working to reestablish a more usual progression through the phases of the visit: ‘then just let me write it down here’ (line 20, also earlier in the interaction, not shown). In lines 25–26, the doctor acknowledges that there is a story to be told, thus putting on the table the reason for the consultation, and he announces in line 29 that they will properly start the consultation. It is then and there, in the transition to the file-filling activity, that we see the diminutive employed in the design of the age question (line 31).

Whereas the new activities launched with diminutivized turns vary, as seen in the extracts discussed in the earlier transition subsections, what all cases in this section have in common is that a diminutive form gets selected in turns that manage a transition in the progression of the consultation, in moving from one phase or activity to the next. Importantly, this analysis is able to account for the variable use of diminutivized and non-diminutivized forms with the same recipients, in accordance with where they are and what they are doing at that moment within the unfolding consultation.

Discussion and conclusions

In order to explore the interactional and pragmatic function(s) of diminutives in Brazilian obstetric and gynecological consultations, we have adopted an endogenous comparative method—we have identified cases where doctors use the diminutive form of a lexical item in close proximity to its base form. This analytic procedure revealed that diminutives, which in general serve a mitigating function, are used by doctors systematically in particular sequences of action, thereby allowing a reconceptualization of what is meant by ‘mitigation’, and where, specifically, it is deemed a relevant component of action by participants in this setting.

We began our analysis in Diminutives in action, part 1: Unpacking ‘mitigation’ by demonstrating that what might canonically be called ‘mitigation’ via diminutivization occurs in two specific actions: (i) offering reassurance to patients in responsive turns, and (ii) attenuating the physical intrusiveness of current or future actions. That diminutives, with their base semantics of ‘smallness’, are systematically deployed in these two sorts of actions, is inextricably linked to the medical setting and clinical activities underway: (i) smallness is frequently a positive or ‘good news’ characteristic of referents within clinical interactions (see Beach Reference Beach2019), and thus the indexation of smallness can be used to offer reassurance to patients; and (ii) medical devices are presented as minimally intrusive into the patient's body through indexation of their small size, thereby painting the upcoming procedure in an arguably less uncomfortable, more agreeable light. Thus, grammatical indexations of ‘smallness’, through the use of diminutivization, become ‘accomplice to’ (Heritage Reference Heritage, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984:299; Jefferson Reference Jefferson, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984:216) the achievement of two specific actions in these obstetric and gynecological data.

In Diminutives in action, part 2: Pursuits and transitions, we then turned to explore two distinct, yet no less recurrent, sequential environments in which diminutive formulations are observed in these data—namely, (i) in response to resistance from patients to advice, recommendations, or some other aspect of the diagnosis or prognosis of their condition, in active pursuit of an acquiescent response; and (ii) in transitioning from one activity or phase to another. In both sets of cases, including the subtypes of transitions explored—that is, inserted activities and questions of age—we propose that what specifically is being mitigated through the use of the diminutive is the speaker's expression of deontic authority over the progression of the consultation. Deontic authority is broadly conceived of as the capacity of a participant to determine courses of action (see Stevanovic & Peräkylä Reference Stevanovic and Peräkylä2012), which in recent work has been used to operationalize ‘agency’ at the local, sequential level (Raymond, Clift, & Heritage Reference Raymond, Clift and Heritage2021). Pursuits and transitions, the two actions identified here, are both demonstrably agentive, with much of that agency deriving from their producer's thereby enacted deontic rights—through the very production of the action—to determine how the interaction will proceed. In the first case, pursuits cast patients’ prior actions as insufficient or otherwise inapposite, thereby actively renewing the relevance of a revised response from them in next position, as opposed to allowing the already-offered response to stand. And in the second case, when doctors enact transitions into next phases of the consultation, they likewise plainly effectuate an action that exercises deontic authority over what the participants will do next. That diminutives are so regularly produced as part of these two specific actions suggests that the precise sort of mitigation they deliver is geared toward attenuating the expression of deontic authority. That is, we argue that it is precisely due to the intrinsic local-sequential deontic implications of these specific actions (pursuits and transitions) that diminutivization is deemed interactionally appropriate as a means of militating against some of the deontic primacy inherently conveyed through the actions.

This reconceptualization of mitigation—interrogating it and its components at varying levels of specificity, dimensionality, or ‘granularity’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2000; Fox & Raymond Reference Fox, Raymond, Steensig, Jørgensen, Lindström, Mikkelsen, Suomalainen and Sørensen2024)—not only demonstrates stronger ‘empirical “bite”’ (Evans & Levinson Reference Evans and Levinson2009:475) by being more tightly tethered to the details of participants’ real-time contributions to interaction; it also sets the stage for a range of possible new lines of inquiry. It is a matter for future research to determine, for example, which of these particularized forms of ‘mitigation’ are used in other situated contexts—both in other medical and institutional settings, as well as in mundane conversation—and whether these usages prove more or less recurrent in other languages and cultural contexts (for a comparable case in Spanish, see Raymond & Fox Reference Raymond, Fox, Ono and Thompson2020:123–27). One of the advantages of unpacking a concept like ‘mitigation’ into its constitutive sequential and action particulars is that those same sequential and action environments can be targeted in other data to see if diminutives—or indeed some other resource—might be deployed there to similar effect. While beyond the scope of the present inquiry to offer a systematic comparison to another corpus of data, it can be noted that in a comparably sized dataset from Brazilian urology clinicsFootnote 5 (to which Ostermann has access), there are no instances of diminutives being used to launch the physical examination, including in turns delivering instructions on how to arrange one's body in preparation for the digital rectal examination. The gender makeup of these consultations is of course different than in the obstetric and gynecological data we examined in the present study, thus also inviting future inquiry into how considerations of gender may intersect with the specific sequential and action environments described here. Lastly, in these and other situated contexts, exploration of participants’ multimodal conduct, and how features such as facial expressions (e.g. of concern; Peräkylä & Ruusuvuori Reference Peräkylä, Ruusuvuori, Peräkylä and Sorjonen2012) may intersect with the deployment and interpretation of diminutives, would be a worthwhile area for further investigation.

In conclusion, then, we aim to have offered a contribution that is both methodologically and theoretically innovative, while at the same time not sacrificing our attention to the details of the empirical data. We hope that this analysis inspires future morphological inquiries from conversation-analytic and interactional perspectives, which have only recently begun to target such resources explicitly (see Keevallik Reference Keevallik2011; Bolden Reference Bolden, Sorjonen, Raevaara and Couper-Kuhlen2017; Stevanovic Reference Stevanovic, Sorjonen, Raevaara and Couper-Kuhlen2017; Raymond Reference Raymond2022), and we look forward to continued refinement of the social-interactional concepts and phenomena used to account for their deployment and interpretation in naturally occurring social interaction.