INTRODUCTION

Technologies are often thought to influence language (cf. Herring Reference Herring2003), and as access to the internet and its myriad communicative applications has surged over the past two decades, public discourse about its influence has become commonplace in networked society. In many contexts, metalinguistic terms like netspeak and chatspeak circulate as names for a perceived language variety originating in internet discourse (cf. Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2006a). This article examines the enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2007) of an internet-specific language variety and the features comprising it, exploring the foundations of this process in ideologies of language and technology.

To offer some prefatory data: on the popular internet social network site Facebook, member-created groups forge affiliation based on cultural interests, social causes, and so forth. The titles of several groups on the site, given in (1), illustrate a shared stance towards perceived internet-specific linguistic practices.

Relatedly, on the collaborative online slang dictionary Urban Dictionary, the metalinguistic terms chatspeak and netspeak are defined and exemplified as follows:

These examples are among the many and varied cultural artifacts that invoke notions of distinctive online linguistic practice—including online blogs, discussion threads, glossaries, translators, and usage guides, as well as offline novels, comics, newspapers, newscasts, teachers' guides, advertisements, t-shirts, jewelry, and academic research. These examples also illustrate several key ideological themes that I argue are central to enregistering internet language: Footnote 2 linguistic correctness, a distinction between “real life” and that which happens on the internet, technology-driven language change, social acceptability, and English language protectionism.

After providing theoretical background, I begin with a description of scholarly treatment of computer-mediated communication (CMC), focusing on the tendency to categorize linguistic practices online as constituting distinct registers. I follow this with an account of the North American mass media's use of the terms netspeak and chatspeak, arguing that these terms have come to share a basic underlying denotation and can be considered part of the metadiscursive process of enregistering internet language. Third, I analyze an online speech chain comprising a newspaper column and two responsive comment threads in which internet language is the focus of interactive metadiscourse. Finally, I discuss this enregisterment process in light of empirical findings regarding linguistic practice occurring via the internet, underscoring the essentially ideological nature of enregisterment, and discuss implications for the application of indexical order to enregisterment.

ENREGISTERMENT, STANDARD LANGUAGE IDEOLOGY, AND TECHNOLOGICAL DETERMINISM

As introduced by Agha (Reference Agha2003:231), enregisterment is how “a linguistic repertoire becomes differentiable within a language as a socially recognized register of forms” (see also Agha Reference Agha2005, Reference Agha2007, Beal Reference Beal2009, Goebel Reference Goebel2007, Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009, Johnstone, Andrus, & Danielson Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006, Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008, Remlinger Reference Remlinger2009). Through the process of enregisterment, sets of linguistic features are conceived as distinctive, imbued with social meaning linked to social personae, and linked to what are perceived as distinct varieties of language (or “registers”). Several analyses have further developed Agha's work by utilizing Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2003) framework of indexical order to show how regional dialect features undergo enregisterment.

In Silverstein's scheme, the valorization of linguistic features can be explicated through dialectics between properties indexed to features. An index is a sign that points to or indicates some property related to it, either naturally (smoke indexes fire) or socially constructed (a three-piece suit may index formality, professionalism, or social class). Linguistic features may index social properties such as a speaker's region, gender, style, or stance (e.g. postvocalic rhoticity in English may index a speaker's Americanness). Social indices are interpreted contextually, and features may have different indices at different times, in different settings, as used by different speakers to different listeners. Silverstein calls the strata of meanings indexed by linguistic features orders of indexicality.

Orders of indexicality build: any nth + 1-order index presupposes an nth-order index, such that indices emerge through (and are dialectical with) other indices. For instance, in examining “Pittsburghese,” Johnstone and colleagues (Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006) show that certain features, such as /aw/ monophthongization, are sociodemographically correlated with speakers in Southwestern Pennsylvania, which establishes a first-order (nth-order) index of linguistic form to social property. When those regionally distributed features become noticed and metapragmatically linked to regional speech, a second-order (nth + 1-order) index is established. When they are objectified and metadiscursively linked to stereotypic personae, a third-order (nth + 1 + 1-order) index is established, and the features are enregistered as belonging to a variety folk-named “Pittsburghese.”

However, it has been pointed out that enregistered features need not be those that a linguist's analysis would show to be distinctly distributed (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009, Remlinger Reference Remlinger2009), and linguists also participate in enregisterment when they determine which features are characteristic of which varieties (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009). It is therefore unclear what kind of feature correlation need be present in order to motivate feature enregisterment, or indeed whether a correlational nth-order index is a requirement for enregisterment. I argue that internet language provides an example of enregisterment wherein a correlational index is not presupposed by social indices, showing very plainly that enregisterment is not necessarily a matter of featural distribution, but rather an outcome of sociocultural and historical context. Enregisterment is an ideological process whereby speakers' perceptions of linguistic variation, social structure, and other pertinent concepts are put to use in construing practices as group- and/or variety-specific. Ideologies of language are subconscious heuristics through which speakers perceive and explain patterns of linguistic structure and use (Irvine & Gal Reference Garner2000, Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity and Kroskrity2000, Mertz Reference Mertz, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998, Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Clyne, Hanks and Hofbauer1979, Woolard Reference Woolard, Schieffelin, Woolard and Kroskrity1998), and an enregistered variety brings those heuristics into observable and conscious focus, sharpening them into a central organizing concept that specifies (to varying degree) the parameters of a variety and its speakers (or nonspeakers).

Enregistered varieties are both products of language ideologies and key mechanisms of ideological (re)production: an enregistered variety provides the possibility that speakers will perceive linguistic features—including novel features—as belonging to the variety. This dialectic can serve to create, perpetuate, or alter existing ideologies. The data I present show the relevance of standard language ideologies, dominant in the context of American English, to the enregisterment of internet language. These are ideologies that privilege “Standard English,” value linguistic or grammatical “correctness,” and cast negative judgment on speakers for deviance from these perceived norms (Bailey Reference Bailey1991, Bonfiglio Reference Bonfiglio2002, Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2001, Cameron Reference Cameron1995, Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green1997, L. Milroy Reference Milroy2000, J. Milroy Reference Milroy2001, Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999, Mugglestone Reference Mugglestone1997, Preston Reference Preston1996, Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Brenneis and Macaulay1996, Reference Silverstein2003). I argue that the notion of “Standard English” is crucial to the enregisterment of internet language, thus one enregistered variety plays a key role in the enregisterment of another; at the same time, the enregisterment of internet language affects ideologies of Standard English.

Just as important to internet language are ideologies about technology. Prior analyses have explicated ideologies driving enregisterment in notions of place, showing that local dialects are enregistered in part through the belief that different localities will have different speech patterns (on “Pittsburghese” see Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009, Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006, Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008; on “Yooper” see Remlinger Reference Remlinger2009). In his treatment of Received Pronunciation, Agha (Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2005) has also shown that regional dialect features can become linked to supraregional social prestige through enregisterment. While the enregisterment of internet language is similar to these other cases, it is also fundamentally different for at least two reasons. First, the internet is not a geographically bounded place with local, place-distributed linguistic features; the internet also has no clearly definable population of “speakers.” Second, communication via the internet, like most CMC, is predominantly text-based and typed, rather than spoken. Thus, the factors laying the foundation for enregisterment are likely somewhat different from those underlying regional dialect enregisterment.

Especially central to the enregisterment of internet language are beliefs that technologies have some inevitable consequence on social practice—a form of technological determinism. A deterministic view holds that technology inherently and autonomously influences society, though this term is applied to views that admit to varying degrees of individual agency and relevance of sociocultural factors (Bimber Reference Bimber, Marx and Smith1994, Chandler Reference Chandler1996, Dahlberg Reference Dahlberg2004, Herring Reference Herring1999, Reference Herring2004, Hutchby Reference Hutchby2001:14–20, Smith Reference Smith, Marx and Smith1994, Thurlow, Lengel, & Tomic Reference Thurlow, Lengel and Tomic2004:40–44). Much earlier research on CMC could be interpreted as somewhat technologically deterministic (if unintentionally so), when claims were made that some features of computer technology—its textual basis, asynchronicity, lack of nonverbal cues, or unfamiliar turn-taking mechanisms—determined users' experience or satisfaction with it (e.g. Daft & Lengel Reference Daft and Lengel1986, Herring Reference Herring1996, Kiesler, Siegel, & McGuire Reference Kiesler, Siegel and McGuire1984, Ko Reference Ko1996, McCarthy, Wright, & Monk Reference McCarthy, Wright and Monk1996, Murray Reference Murray and Coleman1989, Rezabek & Cochenour Reference Rezabek and Cochenour1998, Rice & Love Reference Rice and Love1987, Sproull & Kiesler Reference Sproull and Kiesler1991; for an overview, see Dahlberg Reference Dahlberg2004).

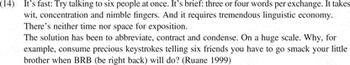

The viewpoint of technological determinism in CMC research has been widely critiqued, and more recently CMC interactions have come to be viewed as sites of potentiality rather than inevitability. Communicative technologies carry both constraints and affordances, which are not deterministic as to their use or impact (see Hutchby Reference Hutchby2001, Lee Reference Lee2007). Yet the viewpoint that a medium in some sense determines what happens in it is present in the way that public discourse frames the internet, and it is highly visible in the way that language in particular is discussed in relation to the internet. The next section shows that this view has also been present in academic discourse about language on the internet.

ACADEMIC ENREGISTERMENT IN CMC SCHOLARSHIP

There is by now a good amount of scholarship focused on language in CMC.Footnote 3 Much of this work has foregrounded the medium in its analysis of language, utilizing somewhat deterministic explanations for linguistic patterns. In particular, a much-belabored concern has been CMC's relationship to “speaking” and “writing,” considered to be fundamentally different modes of language with distinct paradigmatic features (e.g. Biber Reference Biber1988, Chafe & Danielewicz Reference Chafe, Danielewicz, Horowitz and Samuels1987). Early CMC scholars were intrigued by the fact that CMC usage seems to encompass canonical features of both speaking and writing: it may be informal, synchronous, and ephemeral—“like speech”—and/or editable, text-based, and asynchronous—“like writing.”

In working from the analytical foundation of a strong distinction between spoken and written language, many scholars characterized language in CMC, or in particular CMC applications, as unique, bounded, and distinct in their “in-between-ness:” early electronic messages as “a hybrid language variety” or “hybrid register” (Ferrara, Brunner, & Whittemore Reference Ferrara, Brunner and Whittemore1991:10), email as “written speech” (Maynor Reference Maynor, Little and Montgomery1994), Bulletin Board Systems as a “new variety of English,” “so clearly a ‘hybrid’ variety of English” (Collot & Belmore Reference Collot, Belmore and Herring1996:15, 28). Such characterizations persist in more recent accounts: the internet as a “third medium” (Zitzen & Stein Reference Zitzen and Stein2004:984; see also Crystal Reference Crystal2006:52), chat as “a newly emerging, hybrid form with its own characteristics and uses” (Al-Sa'Di & Hamdan Reference Al-Sa'Di and Hamdan2005:422), the internet as “a novel medium combining spoken, written, and electronic properties” (Crystal Reference Crystal2006:52), instant messaging as “a vibrant new medium of communication with its own unique style” and “a hybrid” (Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008:25, 24).Footnote 4

The technical factors to which CMC's “in-between-ness” are typically attributed are the constraints and affordances of text-based dialogue, especially asynchronicity in some applications such as email (where a time lag exists between messages exchanged), synchronicity in other applications such as instant messaging (IM), where participants presumably seek to exchange messages quickly to approximate real-time, face-to-face conversation, and the modality of typewritten text across virtually all applications (for discussion of taxonomies of CMC, see Herring Reference Herring2007). These technical factors couple with the idea that internet interaction tends to represent a “casual” space for written language use that was somewhat unprecedented before widespread CMC.

When scholars isolate medium-bounded contexts and characterize the linguistic patterns within them as emerging from those contexts, they imply that new technologies breed new language varieties; that a medium in some sense determines the language used there. As Herring (Reference Herring2004:27) has noted, scholars tend to research technologies seen as “new,” an approach that “overestimates the novelty of much CMC.”Footnote 5 Overall, the medium (typing versus speaking; email versus chat) has tended to be examined without equivalent attention to social parameters within, or surrounding, the medium. In this way, a technologically deterministic slant has been present in academic discourse, and academic discourse has thereby contributed to the enregisterment of internet language.Footnote 6

As noted by Androutsopoulos (Reference Androutsopoulos2006a:2), the academic construction of internet language as unique and medium-dependent is exemplified by Crystal's (Reference Crystal2006) uptake of the term Netspeak to denote internet language. Crystal (Reference Crystal2006:20) defines Netspeak as:

a type of language displaying features that are unique to the Internet, and encountered in all of the above [internet-based] situations, arising out of its character as a medium which is electronic, global and interactive.

Such a term denotes one variety of language that is specific to the internet and independent of social differentiation: the medium determines linguistic practice. Crystal's list of Netspeak features includes lexical items that belong “exclusively to the Internet” (86); various types of abbreviation—including acronyms for nouns or whole phrases, orthographic reduction of letters, and rebus replacements of letter combinations; nonstandard capitalization and punctuation; and nonstandard spelling such as replacements of <s> with <z> (86–98).

As Dürscheid (Reference Dürscheid, Pittner, Pittner and Schütte2004) among others has pointed out, there are two main problems with Crystal's formulation. First, many features named as belonging to Netspeak have long been prevalently used in other written contexts, including private correspondence (e.g. Elspaß Reference Elspaß2002, cited in Dürscheid Reference Dürscheid, Pittner, Pittner and Schütte2004:6), personal note-taking (Janda Reference Janda1985), and telegraph messages (cf. Baron Reference Baron2002) (this point is also discussed in Herring Reference Herring2004 and Shortis Reference Shortis, Posteguillo, Esteve and Gea-Valor2007; for non-internet-specific discussions of the prevalence and significance of orthographic variation, see, for instance, Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2000, Jaffe Reference Jaffe2000, Sebba Reference Sebba2007). Second, while some features may in fact emerge specifically within the bounds of internet discourse, they will not be used uniformly across every setting or by every user of the internet (cf. Hård af Segerstad Reference Hård af Segerstad2002). In other words, what shapes language use in online environments is not just a matter of its being used online. As with any other use of language, online language use varies by (at least) what format or genre it is used in (chat, email, instant messaging, message boards, blogs, websites, etc.) and the social characteristics and relationships of its users.

Dürscheid's critique resonates in studies of CMC that recognize the importance of sociocultural factors, in addition to the medium, in analyzing linguistic patterns in a given medium (e.g. Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos2006b, Baron Reference Baron2000, Reference Baron2004, Hård af Segerstad Reference Hård af Segerstad2002, Herring & Zelenkauskaite Reference Herring and Zelenkauskaite2009, Jones & Schieffelin Reference Jones and Schieffelin2009, Montero-Fleta, Monesinos-López, Pérez-Sabater, & Turney Reference Montero-Fleta, Monesinos-López, Pérez-Sabater and Turney2009, Paolillo Reference Paolillo2001, Su Reference Su2003, Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008, Yang Reference Yang2007). In other words, linguistic work on CMC has trended away from determinism and towards more nuanced investigations of how language is used in mediated settings, keeping in mind the affordances of different technologies but not assuming that those will steer language use in one direction or another. Furthermore, many scholars have shown that the linguistic features often claimed to be unique to the internet are not common in certain forms of CMC (discussed further in the General discussion). These authors often present their findings in explicit contradiction to the trope of unique, homogeneous new media language (e.g. Baron Reference Baron2004, Hård af Segerstad Reference Hård af Segerstad2002, Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008, Thurlow Reference Thurlow2003).

However, the use of terms like netspeak does continue in academic contexts;Footnote 7 and the view that there is some distinct variety used across the internet even more frequently surfaces in public discourse (Herring Reference Herring2003, Thurlow Reference Thurlow2003, Thurlow et al. Reference Thurlow, Lengel and Tomic2004). As noted above, these public perceptions are often mentioned in scholarly treatments of CMC, yet metadiscourse about CMC and language use has not been a major focus of scholarly study (though see Iorio Reference Iorio2007). One exception is Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2006), who outlines the mass media's representation of CMC and youth. Thurlow finds that the media tend to portray online language as representing a drastic change in linguistic form that is widespread across internet users; they caricature this form based on a select set of features; and they represent the change as a threat to literacy and social organization.

Though Thurlow's concern is representations of youth language, his analysis more broadly indicates that the internet occupies a place in contemporary ideologies about language, English in particular. Thurlow suggests that metadiscourse about CMC demonstrates a “triple whammy” social panic, wherein adult fears about young people, language, and technology coincide. The following two sections build on Thurlow's work, first, by examining the history of the print media's use of variety-naming terms as evidence of the enregisterment of internet language; second, by examining metadiscourse in online discussion threads to give a broader picture of enregisterment through interactive discourse.

MASS MEDIA METADISCOURSE ABOUT LANGUAGE AND THE INTERNET

In analyses of the history of English and Standard English, the mass media are often taken as key producers and sustainers of standard language ideologies and engines of language standardization (e.g. Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green1997, Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999, Silverstein Reference Silverstein, Brenneis and Macaulay1996). The mass media are also a crucial site of enregisterment in media-heavy societies, as shown in several analyses, including Agha Reference Agha2003 and Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006. This section focuses explicitly on the metalinguistic terms netspeak and chatspeak as used in North American print mass media to trace the enregisterment of internet language.Footnote 8 While the use of a metalinguistic term such as chatspeak in some sense presupposes a referent for its use, it simultaneously constructs a referent each time it is used, potentially changing its denotational scope (Agha Reference Agha2007:64–69, 87–89). At the same time, each use may reinforce or alter indexical links associated with the referent. The use of referring terms thus contributes to enregisterment by metadiscursively constructing language varieties and their social indices. I explore two primary aspects of these terms' usage: their denotation(s), including what linguistic practices they are said to include; and their linkage to social contexts, speaker personae (Agha Reference Agha2003), other language varieties, and so on. I begin with netspeak because it is the earlier occurring (and more prevalent) term in searches of print media.Footnote 9

Netspeak: From lexical register to nonstandard writing

Netspeak has been in public usage since at least 1993 (Bacon Reference Bacon1993), when the internet was still considered a novelty to all but the very technically savvy. In the mid-1990s, the term refers to vocabulary words necessary to use internet applications or talk about them, and netspeak is often framed as a code to be translated into common words, as evidenced in the following examples.

These usages show netspeak naming a code of vocabulary terms (mailing list, newsgroup, snail mail, links) that can be glossed, translated, or defined in non-netspeak. News sources also printed glossaries of netspeak terms at this time, sometimes as sidebar companions to “how to access the internet” articles (Putzel Reference Putzel1994).Footnote 10 In 1996, netspeak was one of US News & World Report's buzzwords—“the language that will shape our world in 1996”—and was defined as a lexicon:

This period also saw the creation of glossaries printed in book form, such as Fahey's (Reference Fahey1994) Net.speak: The internet dictionary. Fahey's book was included in The Star-Ledger's (Newark, NJ, 1998) guide to “computer dictionaries,” which introduces the need for such books with a list of words said to form “a whole new language” related to the internet.

These excerpts indicate that during the mid- and late-1990s, a set of vocabulary words was being enregistered as a lexical register linked to the internet; netspeak was characterized as a unique “argot,” “language,” or “dialect.”

If netspeak was emerging as an enregistered variety, what kinds of social indexicalities did the variety have? In early instances, netspeak was linked to the “insider” status of internet users, a marker of authenticity acquired through genuine participation in internet culture. The author of (9) laments lacking mastery of netspeak and therefore authenticity as an internet user.Footnote 11

Earlier usages of netspeak as a set of vocabulary words focused on the internet as a new sphere of utility and interaction, with a new language being a key determinant of access. They did not often present netspeak or its users as negative, except to the extent that the internet was framed as an exclusive tool. However, as the internet became more widely accessible throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, mass media applications of netspeak came to include linguistic forms seen as emblematic of language online, namely acronyms, other abbreviations, emoticons, and phonetic respellings. These were typically presented as emerging from the desire for participants to communicate quickly in the text-based realm of the internet. Perhaps representing the midpoint of this shift, a 1999 USA Today article titled “Language on the web” mentions both vocabulary words and features, including <lol> ‘laugh out loud’, <ftf> ‘face to face’, and <rotfl> ‘rolling on the floor laughing’ as examples of internet-specific acronyms (Viotti Reference Viotti1999). And a 1999 Seattle Post-Intelligencer article claims that in online chat rooms, “a correctly spelled word is a sign of the inarticulate and an innovative abbreviation is prized above all else” (Harmon Reference Harmon1999); the headline reads “Netspeak seeps into public lexicon …” With this headline we begin to see the linking of netspeak to nonstandardness, and what I call an imperative of containment that stigmatizes the use of internet language in noninternet contexts. Coinciding with the term being used more to refer to language features came an increased scrutiny on netspeak as a potentially negative social force (cf. Thurlow Reference Thurlow2006). I suggest that this came about in part because netspeak features now were ones perceived as flouting standard written English norms.

In 2000, The New York Times ran a review of the book Wired style: Principles of English usage in the digital age under the headline “Capturing netspeak, but not reining it in.” The author, English usage expert Bryan Garner, characterizes the internet's “dialect” as “a written dialect in which punctuation is abandoned, uppercasing is largely unknown (unless you're shouting), and all sorts of acronyms replace phrases” (Garner Reference Garner2000). Two letters to the editor responding to this review illustrate netspeak's formulation as counter to standard language practices with the headlines “The death of grammar” (Woog Reference Woog2000) and “Long live good grammar” (Skogsberg Reference Skogsberg2000). One letter even stylizes (in the sense of Coupland Reference Coupland2001) netspeak as a rhetorical device to demonstrate its detrimental effect on high school students' writing:

The author intentionally departs from the English typically encountered in a major American newspaper, attempting to elicit sympathy from readers. Internet language is characterized through abbreviations (<hi>, <w/>), nonstandard typography (uncapitalized <i>, sentence-initial <it> and <do>), and respellings (<u>). These features are linked to “grammar” by the headline and presented as a threat to standard writing. The idea that internet language might undesirably “seep in” to noninternet contexts—articulating an imperative of containment—occurs consistently in the media from the late 1990s to the present.

By the mid 2000s, most print media uses of netspeak presented acronyms and abbreviations as iconic of the variety, and acronyms and abbreviations were enregistered as netspeak largely through the idea that people make linguistic adaptations to achieve a level of typographical efficiency on the space- and time-constrained internet. Also in this time, the emphasis on netspeak as emerging from youth practices appeared. In 2002, a syndicated Knight Ridder Newspapers piece stylizes the variety and links it to youth:

The first line typifies the variety with respellings (<RU>, <der>, <GR8>) and abbreviations (<abbrz>, <bout>, <mo&mo>, <TLK>, <MSGS>), and the article links these features to people “young enough” to be natively entrenched in digital technology. As Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2006) notes, in public discourse, concern about youth often co-occurs with concern about language, and this is evident especially in news articles from the mid-2000s discussing netspeak. Another Knight Ridder story confronts public concern about young people and netspeak, interviewing David Crystal, Naomi Baron, Susan Herring, and Simeon Yates—some of the most prolific and respected linguists who research CMC:

Public fears about netspeak are the author's point of departure, writing that purists need not “worry” about netspeak. This frames netspeak in contradistinction to Standard English, highlighted by the article's subheadings “Violations of the rules” and “Normal English has its place.”

These latter typifications differ sharply from earlier instances of netspeak in the print media: rather than lexical items, it is now nonstandard written features—acronyms, abbreviations, respellings—that are enregistered as internet language. These features are portrayed as resulting from the time and space constraints of text-based internet applications. I suggest that these typographical features are akin to the phonological features enregistered in spoken language, such as /aw/ monophthongization in Pittsburghese (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006).Footnote 12 Netspeak also became linked to nonstandardness and youth, and an imperative of containment articulated a normative contextual appropriateness for the variety. In both periods, the idea that the internet gives rise to a distinctive and new set of unified language practices can be interpreted as a form of technological determinism. In the later period, the often negative social evaluation of these language practices can be interpreted as a manifestation of standard language ideologies, where netspeak is enregistered as a nonstandard language variety and, hence, an object of public concern.

Chatspeak: From chatrooms to the internet

According to my research, the print media's use of chatspeak comes later than its use of netspeak and from the earliest instances, acronyms and abbreviations, framed as accommodations to synchronous text-based interaction, form the core of its reference. The first instance occurs in 1998, when a Dallas Morning News article reports that some of psychologist Sherry Turkle's chatroom research participants found that “chat is more real than RL—Real Life in chat-speak” (Bedell Reference Bedell1998). As with early instances of netspeak, chatspeak words are glossed, but these are largely limited to spelling out acronyms, as in this 1999 USA Today article about online dating:

A 1999 Washington Post article (reprinted across the country in several major papers) also indicates an early focus on both abbreviations and youth, describing teens' use of “shorthand” in chatroom interaction as a means of achieving speed:

The article also mentions a lack of vowels as common in chatspeak, quotes teens who say that chatspeak words are unspeakable, and offers a glossary of acronyms such as <CYA> ‘see ya’, <OMG> ‘oh my gosh/god’, <TTFN> ‘ta-ta for now’, and <B/F> ‘boyfriend’. Several other instances of chatspeak refer to language composed of abbreviations from 1999 through the 2000s. For example, a Chicago Tribune story from 2000 emphasizes acronyms, youth, and emoticons:

As with netspeak, several glossaries of chatspeak appear (e.g. Fisher Reference Fisher2000), and chatspeak is linked to internet “insider” status. The same 2000 Chicago Tribune story excerpted above portrays chatspeak as a barrier to internet participation for the unversed, a new code that must be learned for full participation:

Several writers also warn against using chatspeak in noninternet environments, echoing the imperative for containment of internet language, such as this 2004 piece in the Fort-Worth Star Telegram which divorces chatspeak from “actual communication:”

Interestingly, while many earlier instances of chatspeak suggest that it emerged specifically from chatrooms (such as through Internet Relay Chat), later uses sometimes attribute the variety to another form of synchronous CMC—instant messaging (IM):

Later uses like this broaden the term chatspeak to apply to these particular language features used across internet applications. Thus, chatspeak refers to a set of features of a medium-dependent, not application-dependent, language variety.Footnote 13 Whereas the denotational history of netspeak shows a shift in what features were enregistered, that of chatspeak shows a shift in what contexts were linked to the features, broadening to internet contexts generally—perceived as similar in their technological constraints and hence linguistic practice.

Chatspeak uses also show public concern about the internet's effect on language, writing, and English, especially in the latter part of the 2000s. For instance, following the release of a 2008 Pew Research study,Footnote 14 a writer in the Los Angeles Times bemoaned English's demise in the face of chatspeak:

In invoking the imperative of containment, this example highlights how extremely negative (even violent) stances sometimes are towards internet language.

Enregistering internet language; enregistering features of internet language

This section has provided evidence for the enregisterment of internet language by examining the uses of two metalinguistic terms in the mass print media over the past two decades. I have said that netspeak appears to have occurred earlier and denoted a lexical register, but around the time chatspeak emerged, both terms encompassed a common set of linguistic features—acronyms, other abbreviations, and nonstandard writing practices. At the time of the writing of this article, in late 2009, these two terms are often treated as synonyms, demonstrated by the cross-referencing definition in (3). These data suggest that over this relatively short period of time, there has consistently been a concept of internet language in the public imagination, though its bounds and applications have changed. Netspeak shifts to include nonstandard features; chatspeak grows to encompass broader internet contexts; the terms' denotations and social indexical links converge.

The case of internet language shows that it is useful to talk about the enregisterment of a variety as partially separate from the enregisterment of the variety's features. The enregisterment of internet language—the recognition and valorization of linguistic forms linked to the internet—has been happening since the early 1990s and perhaps earlier, when ideas emerged alongside new technology that the internet gave rise to unique linguistic practices. But while the concept of the variety has persisted, its specifications have varied—the enregisterment of internet language, the variety, is different from the enregisterment of lexical items or acronyms, the features of the variety. This enregisterment process is motivated by a widespread and compelling perception that the internet is a “new,” “different,” “revolutionary,” and ultimately troubling social space (Paradis Reference Paradis2005), along with experience or perception of the internet as a place for synchronous written communication. For this process to be analyzed via the framework of Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2003) indexical order (after, e.g., Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006), one would need to identify a set of features as correlated with a sociodemographic property or pragmatic function, such as internet users or internet communication. This index would then be presupposed by second- and higher-order indexicalities related to personae, register, social meaning, and so forth. But it is not first and foremost a correlation between the internet and the use of these features that precipitates their enregisterment; it is rather the perception that there is some correlation, driven by the belief that internet language is unique. This belief is related to technological determinism. I discuss these issues further in the General discussion.

The metalinguistic referring terms netspeak and chatspeak offer just one possible departure point for investigating how metadiscourse configures an internet-specific language variety. Excerpts from the mass media demonstrate convergence on the features attributed to this variety and its social valuation. While the mass media publicly circulate these tropes about language, to understand enregisterment we must also investigate the processes by which values are transmitted between the media and speakers (cf. Spitulnik Reference Spitulnik1997) and by which speakers negotiate and circulate ideas about language (cf. Agha Reference Agha2007:228–32, Johnstone & Baumgardt Reference Johnstone and Baumgardt2004).

METADISCOURSE IN AN ONLINE SPEECH CHAIN: LANGUAGE ON THE INTERNET ABOUT LANGUAGE ON THE INTERNET

In their metadiscursive descriptions of communicative phenomena, the mass media formulate models of language that may be received by others and transmitted through interaction. To account for these processes, Agha (Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2007) uses the concept of speech chains—linked series of encounters that are a central mechanism of enregisterment, the means through which semiotic and social values are transmitted and changed. While the mass media might begin a speech chain as sender of a certain message, the chain does not necessarily end at the audience as receiver of that message, since the message can go on to be transmitted and altered by the audience in extensions of the chain. In this section, I analyze metadiscourse in a multi-sited speech chain that begins with an online mass communicative prompt and continues with readers' responses through two online discussion threads. By examining speech chains such as these, we can see how media messages are echoed or reanalyzed by recipients and how internet users—as interactive with the mass media—contribute to the enregisterment of internet language. Each type of metadiscourse is situated within a cultural context that includes the other.

I first overview the data and then analyze how internet language is metadiscursively characterized by participants in terms of linguistic features, Standard English, sociohistorical explanations, and speaker personae.

Overview

This speech chain consists of readers commenting on an opinion column published online by the Chicago Maroon, the student newspaper of the University of Chicago (Hogan Reference Hogan2006). Readers left comments directly on the column's webpage, and the column was multiply linked to by readers, as is typical of heavily-read internet content.Footnote 15 Among these links was a post on the social bookmarking website Digg (http://digg.com), which enables site members to share links and discuss online content.Footnote 16 At the time I captured the data, Maroon held 91 comments while Digg held 214 comments, amounting to 305 comments between the two texts, from 266 delimited commenters.Footnote 17 Although two separate comment threads are discussed here, I consider them part of one speech chain, since they emerge from the same originating prompt.

Column author Hogan conveys dislike for what he terms AOL-speak,Footnote 18 “an increasingly new and incomprehensible language.” (It is perhaps useful for the reader to keep in mind that this was published in a university newspaper, which presumably serves students who may typically be categorized as “youth,” or at least “young adults.”) The following excerpt encapsulates the column's thesis:

I have become convinced that these abhorrent abbreviations are nothing less than an insidious linguistic plague slowly but surely wreaking havoc on competent communication everywhere. Cute and cuddly abbreviations such as “LOL” and “BFF” may save time and allow for faster, more efficient correspondence, but that is precisely the problem. The efficiency of AOL-speak not only erodes relationships by dumbing down how people talk to one another but it also degrades the English language itself. (Hogan Reference Hogan2006)

When broken down, the column makes three primary claims: First, a type of language called AOL-speak exists that is characterized by the use of “abbreviations” (including acronyms). Second, this variety is motivated by a desire for efficiency when communicating online. Third, this variety contributes to the demise of the English language. The column's stance largely aligns with the content of the mass media presented above. It also aligns with standard language ideologies about English.

These claims put forth a model of language for readers to negotiate, and readers' comments echo much of the claims' main substance. The existence of AOL-speak is hardly challenged; neither is its characterization as an abbreviated form of English. The term AOL-speak itself is used in the comments of thirty-two separate commenters, along with numerous other terms that invoke the internet (netspeak and chatspeak among them).Footnote 19 Participants also make reference to internet language through demonstrative deictics (such as “talk like that”) and the pronominal it that presupposes AOL-speak as a given referent. For example:Footnote 20

Other metalinguistic terms invoke nonstandardness, informality, slang, or poor typing, construing internet language in juxtaposition to normative English. Table 1 outlines all metalinguistic referring terms for internet language found in the data, subcategorized by specific indices each might be thought to carry based on the content of the term.

Table 1. Metalinguistic terms referring to internet language, with bare counts of their occurrence across the Digg and Maroon threads (no count indicates the variant occurs only once; asterisk indicates orthographic variation within the variant term).

While this list shows that many discussion participants disagree with Hogan's terminology, only one commenter challenges the notion that there exists a particular type of language corresponding to what is meant by AOL-speak. Participants here share a concept of a variety of language that is internet-specific that subsumes terminological differences, giving further evidence for enregisterment (as argued in the prior section).Footnote 21 There is contestation, but it is not about what terms like AOL-speak refer to; this much seems taken for granted by discussion participants as common ground. This is seen in how consistently commenters' metadiscourse configures the features of the variety.

Features enregistered as internet language

These speech-chain participants by and large orient to the definition of internet language as a set of orthographic and linguistic features. Following the column's emphasis, commenters primarily discuss abbreviations and acronyms. Mention of “abbreviations” is made explicit by twenty-five different commenters, with more indirect allusions to “shortening” throughout. Thirty-eight different participants make explicit reference either to “acronyms” generally or to specific acronyms, most often <LOL>. Additionally, respellings that mimic phonetic characteristics, such as replacing letters with numbers (<gr8>), are commonly invoked (cf. Sebba Reference Sebba2007, Thurlow Reference Thurlow2003). As seen in Table 1, several referring terms contain the notion of “abbreviations” within them, such as in the comment below, where Andy couches the referring term IM-speak within the description of its features, “these shortened IM-speak words”:

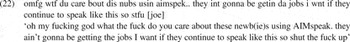

Example (21) shows that while some participants talk explicitly about “abbreviations,” others define the variety by demonstrating it. The most common exemplifications are <LOL>, <BRB>, <OMG>, and <WTF> ‘what the fuck’ for acronyms; and <u> ‘you’ for alternative spellings. More extreme modes of demonstration consist of participants stylizing the variety (as the mass media also does) as in (22).

Demonstration and discussion of textual shortenings link the internet to technology-adaptive nonstandard written renderings of words or phrases that could also be produced in spoken language, and perhaps the idea of written manipulation of speech itself causes some anxiety.

Strictly written orthographic features involving punctuation and capitalization are also discussed in the comments, but only in a few instances. Yet mentions of capitalization are embedded within some of the most extremely negative of comments, as shown in MeridianBlade's stylization:

The relative lack of concern for punctuation or capitalization is noteworthy here, because these orthographic features are domains where nonstandard usage is very common in instant messaging and other forms of CMC (see General discussion). A handful of participants attribute other features to internet language, including typos or “incorrect spelling,” “smiley faces,” and “bad grammar.” In terms of the typification of internet language features, then, this speech chain is generally consonant with mass media metadiscourse; this convergence happens against a common backdrop of standard language ideologies.

Internet language and standard English: The imperative of containment

The discussion above hints at my central claim that internet language features are enregistered as being in contrast and even conflict with Standard English. This metadiscourse shows that the process of enregisterment of one language variety often depends upon the existence of other enregistered varieties within speakers' schemata of language variation (Remlinger Reference Remlinger2009 points to similar processes). Hogan's column claims that AOL-speak poses danger to English; while participants do not often use the term standard (“standard English” occurs only twice), they frequently employ notions of correctness or normality. Participants juxtapose internet language features to “proper English,” “perfect English,” “correct English,” “coherent English,” and “the actual English language.” Participants also index standardness when they contrast internet language with the practices of people who “type normally,” “form sentences,” “type properly,” “speak coherently,” “write properly,” “[use] proper ways of speaking,” and “correctly us[e] the written language.” Because standard ideologies are commonly articulated via appeals to “grammar” (cf. Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999), I argue that participants also indirectly reference “Standard English” through mentions of “correct grammar,” “proper punctuation and grammar,” and “good grammar and spelling.” These metalinguistic acts of reference, as with those to netspeak or chatspeak, point to and re-establish the notion of standard language; again, the terminological differences are subsumed by a conceptual commonality.

Internet language and Standard English are also distinguished by the domains in which participants claim they are acceptable. Several participants argue that users of internet language should be able to switch into Standard English when the situation demands it. The imperative of containment is visible here in the contexts in which the two varieties are said to be acceptable, a summary of which is given in Table 2. Participants often juxtapose pairs of settings that require different types of language: formal and casual, school and internet, business and internet, formal writing and informal chatting, IM chats and written letters.

Table 2. Summarization of reported contexts of use for internet language and Standard English.

An especially interesting aspect of the imperative of containment is how notions of speech and writing are deployed within participants' metadiscourse. As seen in the mass media examples, comment thread participants talk about internet language features as “slipping” or “creeping” into unwarranted contexts, including contexts of speech. By most scholarly accounts, written English forms a zone where standardization has been most successful and where nonstandard features are least acceptable (cf. Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999; see also Sebba Reference Sebba2007 for a complementary view). As Bucholtz (Reference Bucholtz2001) notes, standard language ideologies typically characterize varieties of spoken English as nonstandard when they diverge from the rules of written English. Internet language indeed consists of divergences from Standard Written English, yet participants claim that internet language should be confined to what are fundamentally written domains. Meanwhile, internet language is also not to be used in more “formal” online settings, such as emails to a boss.

This suggests that for these participants, the distinction between standard and nonstandard English obtains primarily through contexts dichotomized by social function, rather than modality—formal versus casual, business versus personal, not writing versus speaking. Indeed, while most of the features ascribed to internet language are dependent upon a written modality, they are not dependent upon being used in one written modality versus another, and in practice many of these textual strategies—namely abbreviations, acronyms, and phonetic respellings—are used across written contexts, from the handwritten to the typewritten to the printed sign (see Shortis Reference Shortis, Posteguillo, Esteve and Gea-Valor2007). This underscores the importance of technological determinism to the enregisterment of internet language. As seen in Table 2, internet language is never said to be acceptable in noninternet contexts, yet it is also said to be unacceptable in certain internet contexts. Thus, in this case, I suggest that certain types of online interaction are characterized as internet interactions, and these contexts form the conceptual foundations that motivate the enregisterment of internet language features. For most participants in this data, email is not one of these contexts, likely because it is perceived as used for more formal purposes; but instant messaging is, because it is used more casually (see also Quan-Haase Reference Quan-Haase2007, Squires Reference Squires2003).

The foregoing discussion relates to scholars' conclusions that internet language is a “hybrid” between speech and writing, because it shows that speakers' concepts “speech” and “writing” are actually not dichotomous. With the increasing social contexts in which writing is used, distinctions like spoken and written are less important to users than those based on speaker roles and pragmatic functions. Internet language is constructed here as a variety that ought not encroach on Standard English, but what counts as “Standard English” does not include the whole of written English. Thus enregisterment may reinforce some aspects of ideology while reconfiguring others; and indeed may impact the ongoing enregisterment of other language varieties (at least, in this case, Standard English).

Sociohistorical explanations for internet language

The enregisterment of internet language follows fairly recent developments in social infrastructure, and accordingly, Digg and Maroon participants often explain its existence in terms of sociohistorical processes of technological change and language change (or change in language proficiency). The issue of technological change is, as I have said, related to a viewpoint of technological determinism. The issue of language change has been common throughout “the complaint tradition” in English history (Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999; also documented in Bailey Reference Bailey1991), in which public debate has focused on perceived declines in language or literacy.

In this speech chain, communicative technologies are said to catalyze language change, as in krosk's supposition in (24) that new technologies require linguistic adaptation, resulting in “shorthand.”

Some participants also give historical context to internet language by historically situating the technologies implicated, and pointing out that abbreviations and acronyms are not new, as Steve writes in (25).

Steve argues for broader historical perspective and more accuracy in how “internet” is conceptualized, contesting the idea that “internet” can be considered one thing, or that “internet” gave rise to these linguistic innovations. Steve thus resists technological determinism, taking a minority stance among the commenters. Nevertheless, (25) indicates a belief that new settings (yearbooks, BBS, IRC) motivate linguistic change or adaptation to their technical constraints and affordances. Many commenters similarly focus on language change—beyond the context of the internet—as an element of internet language's development.

Most attributions to language change are value-neutral declarations that language always changes, denying that internet language can be any better or worse than other changes. There are, however, disagreements, with claims that internet language is “devolution” not “evolution.” For instance, soupisgoodfood (26) claims that the change is regressive.

The attribution of positive values to language change, including the changes giving rise to internet language, is much more common and co-occurs with affirmations of its efficacy:

Participants making claims about internet language as a positive progression refer to its efficiency, utility, and suitability to the internet, reinforcing the notion of the variety as “shortened” elements of English.

The imperative of containment appears again in several comments claiming that internet language results from a negative change in English proficiency, due to inadequate schooling. In such comments, participants bemoan the negligence of the (presumably) American education system in teaching students grammar and writing:

As Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2006) shows, both technological change and language change are common sites of societal moral panics. When participants orient to the salience of these factors as motivating internet language, they orient to aspects of existing ideologies about the value of Standard English, and about technology as a societal determinant.

Personae linked to internet language

The speech chain also gives evidence of speaker personae—social types—linked to internet language, though this occupies a relatively small portion of the comments. There is an implicit, presumably stable link to an undifferentiated “internet user” who uses internet language, but this in itself does not suffice for explanation, since all participants in this speech chain are internet users, yet most claim not to use internet language. Links to personae are an integral component of enregisterment (Agha Reference Agha2003), and here I offer a brief discussion of this component of the data.

Participants attribute internet language primarily to four broad categories of speakers: youth, females, the lazy or inexperienced (those who do not put forth the effort required to type in standard fashion, including novice internet users), and the uneducated/low-status/unintelligent. These categories often overlap in descriptions, such that gender is hardly mentioned without reference to youth. Table 3 shows these four social categories as evoked by specific referential constructions in the data.

Table 3. Social personae categories linked to internet language (asterisk indicates overlapping categories; brackets indicate author notes).

Just as language change and technological development have often sparked moral panics, the categories of youth, gender, and education status have long been staples of public discourse about nonstandard English (cf. Cameron Reference Cameron1995, Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999); youth and gender have in particular also been common in mass media representations of CMC (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2003, Reference Thurlow2006). It is thus not surprising that these personae linkages occur for internet language; what is perhaps surprising is how relatively little of the metadiscourse draws links to specific personae, focusing instead on the medium of the internet.

Metadiscursive themes in enregistering internet language

This section has overviewed metadiscursive assessments of internet language in an online, interactive speech chain. These assessments are generally positive when internet language is presented as an adaptation to specific settings and negative when it is presented as an unnatural deviation from Standard English. These assessments are interpretable in the context of their connections to other spatially, textually, and temporally disconnected discourse. This speech chain is a temporally-bound snapshot, one chain among many, in the enregisterment of internet language—as evident in the print media, this process has been occurring for over a decade. Furthermore, its foundations predate the internet itself. This speech chain—from the initially printed column to the unfolding, interactive participant responses—emerges within a climate of ideological attitudes toward technology and nonstandard language, and it is a site where those ideologies are reconstructed in light of perceptions of technological and social change.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

I have presented evidence for the enregisterment of internet language from academic discourse, mass media discourse, and interactive internet discourse. My argument has been that two ideological factors most centrally motivate this enregisterment process: standard language ideology and technological determinism. I have argued that these two forces converge in metadiscourse about the internet, and that internet language is foremost an ideological construction based on perceptions of the uniqueness of internet interaction and its language. Here, I elaborate on my claim that this enregisterment process does not completely mirror the processes of enregisterment of regional varieties discussed elsewhere, primarily because the enregisterment of internet language does not proceed from linguistic features that bear a “first-order index” of either a sociodemographic category or pragmatic function (as the notion of indexical order has been developed and applied by Johnstone Reference Johnstone2009, Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006, Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008, Remlinger Reference Remlinger2009, Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003).

For regional varieties like “Pittsburghese” and “Yooper,” there is claimed to be an underlying frequency distribution of the enregistered features (what Johnstone and colleagues (Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006:87) have called “preconditions for dialect enregisterment”). This means neither that, for instance, only one variant of a sociolinguistic variable is used in a geographical area, nor that that area is the only area to use that variant. But it might mean that either a) in that area, the variant is more likely to be used than other variants, or b) the variant is more likely to be found in that area than in other areas. If the enregisterment of internet language comes about in a similar manner, we might expect that the relevant features—acronyms, abbreviations, and phonetic respellings—are either more commonly used on the internet than their orthographically standard counterparts are, or more common on the internet than in other settings. This would provide a kind of feature-based first-order indexicality for speakers to “notice” and work into existing sociolinguistic schema. Yet there is evidence that neither of these properties holds true for enregistered internet language features.

First, empirical studies have called into question the notion that these features are more common on the internet than their standard counterparts are. For example, regarding acronyms, both Baron (Reference Baron2004) and Tagliamonte and Denis (Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008) found very few acronyms in English-language instant messaging (IM) conversations. Baron (Reference Baron2004) found only ninety acronyms in a nearly 12,000-word corpus, and many of the variants occurred only once. The form <lol> was most frequent, occurring seventy-six times. In a much larger corpus, Tagliamonte and Denis (Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008) found numerous uses of <lol> (.41% of total words) and <omg> (.11%), but very few instances of other stereotyped forms, including <brb> (.04%) and <wtf> (.02%). Together, all of these features constitute just 2.5% of total words in their corpus. Tagliamonte and Denis also found few cases of <u> relative to the standard variant <you> (8.6% vs. 91.41%, with <u> used by only by twenty-seven speakers out of fifty; Tagliamonte, personal communication), and Baron found only thirty-one “CMC abbreviations” altogether (and reports no cases of <u>).

My own corpus of sixteen IM conversations, collected in 2004, shows similar patterns. The tables below summarize the occurrence in my data of these forms. Table 4 shows the acronyms discussed in Tagliamonte & Denis (Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008) and Baron (Reference Baron2004),Footnote 22 and Table 5 shows two forms of letter substitutions. Each variable shows a preponderance of standard usages compared to nonstandard ones, and few overall stereotyped features.

Table 4. Use of forms in instant-messaging data in a corpus of approximately 10,000 words.

Table 5. Distribution of standard and nonstandard variants for (you) and (are) in instant-messaging data in a corpus of approximately 10,000 words.

However, some nonstandard forms do appear to be more common in IM than their standard counterparts, especially in the domains of punctuation and capitalization. For instance, lowercase <i> rather than uppercase <I> for the first-person pronoun was found commonly (though conditioned by individual) in both Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2008 and my own data, shown in Table 6.Footnote 23

Table 6. Distribution of variants of (I) in two sets of instant-messaging data.

My corpus also shows individual differences in the use of apostrophes in contractions and possessive nouns, where some speakers use apostrophes 100% of the time while others use them 0% of the time; the overall apostrophe usage rate is at just over half (see Squires Reference Squires2007). I believe it to be remarkable that these orthographic features—punctuation and capitalization—are relatively rarely discussed as part of internet language, though their nonstandard versions occur as common variants to their standard versions, and in many cases the nonstandard variants overwhelm the standard ones; this contrasts with the features that are commonly attributed to internet language but are relatively rarely used.Footnote 24

It is more difficult to prove whether or not internet language features are indeed quantitatively used more often in online versus offline contexts, due to the historical lack of serious analysis of vernacular written texts. But as Shortis (Reference Shortis, Posteguillo, Esteve and Gea-Valor2007) and others have argued, the orthographic features that the media have recently focused on have long been commonly used in written arenas outside of those sanctioned by dominant language standards. Shortis provides a number of orthographic features often cited as being common to text-based practice—especially text messaging and internet communication—including vowel omission, letter replacements, and acronyms. He shows that these features have long been part of many vernacular literacy practices, such as trade names, codified occupational and uncodified personal shorthands, and popular culture (such as song lyrics). What is new about these features' role in written practice is that internet discourse documents, publicizes, and diffuses them—not that they are more frequent in internet discourse than in other realms.

This evidence suggests that for the enregistered features of internet language, patterns of usage do not exist that clearly correlate with either “internet user” or “internet.” The construct of internet language (referred to by various terms) glosses over many different patterns of variation in an extremely large sphere of discourse with many different types of speakers, the heterogeneity of which is typically erased. In the empirical studies on IM described above, the subjects were teenagers or young adults, which is precisely the population implicated as personae linked to internet language, yet these speakers did not commonly employ the stereotyped features. Hence, instead of presupposing a sociolinguistic feature correlation, the enregisterment of internet language proceeds from ideas about technology and social space, and language is taken as a way to delineate that social space. It is not the case that features are distributed along “internet/noninternet” lines and come to be perceived as such, but rather that an “internet/noninternet” line is perceived, and features are categorized as belonging on either side of the line. This categorization is based largely on what features are enregistered as belonging to another type of language, Standard English, and which social settings it is perceived as appropriate to.

CONCLUSION

This article has attempted to provide more rigorous analysis of a popular phenomenon—public discourse about language and computer-mediated communication—often noted but rarely interrogated, utilizing a developing theoretical framework for understanding the social significance of language variety. Internet language provides one example of how enregisterment brings the forces that bear on language's significance to the forefront, helping us see which cultural logics, facts, and perceptions are pertinent in a given place at a given time. By taking metadiscourse about language and the internet as a central point of investigation, I have shown the enregisterment of internet language to be interpretable as outcomes of extant dominant ideologies of language and technology. Only a small slice of the enormous potential evidence for this enregisterment has been dealt with, and only a small bit of its complexity is represented here. I hope that more scholars will provide more nuanced analyses of the ever-changing social and linguistic practices involved in computer-mediated communication, and of the value that those practices hold within networked (and nonnetworked) social life.