1 Introduction

Fundraisers know that social pressure affects pro-social behaviour. Past donors are asked to solicit additional donations; university alumni are encouraged to contact and motivate others in their cohort (Reference Meer and RosenMeer & Rosen, 2011); charity events often require participants to raise a certain amount of money from friends and relatives. The use of giving websites that rely on peer pressure is a significant recent development in this area. The website http://www.justgiving.com, set up in 2000, invites visitors to create and personalise a giving webpage, which tracks fundraising goals and progress for a chosen charity and can be shared with friends and family. This site has been used by 13m people and has raised over £770m. Fundraising and donating to charity is free on this website but charity members (over 9,000 charities are registered) pay a transaction fee of 5% (plus credit and debit card fees) on each donation and a monthly membership fee of £15+VAT. The customer who sets up the page exerts direct peer pressure on the lucky friends and relatives who are asked to donate. There is also indirect pressure among potential donors who, when they view the identity of donors and the size of their gift, may be compelled to donate in equal measure, especially since each donation (or lack of it) is public.

The website http://www.virginmoneygiving.com, set up in 2009, also allows users to create personalised webpages dedicated to fundraising events, personal challenges or other special occasions and share those pages with friends and relatives. Customers creating pages and potential donors can view an up-to-date list of sponsors and the sizes of their gifts. Use of the site is free to donors and fundraisers but charges apply to registered charities who pay a one-off flat joining fee (£100 +VAT) and the site takes a 2% commission on donations to cover operating costs.

Why are these sites so popular? Clearly, charities would not register unless they expect to recuperate the joining fee and commission from increased income. Customers are aware that donations are subject to commission but they probably believe they can raise more money this way than by asking friends to donate to a charity directly. People may also use these websites to broadcast their contribution to society; emailing friends and relatives and asking them to donate directly to charity would not provide such publicity or boasting opportunity.

The success of giving websites illustrates that there are motives other than altruism for pro-social behaviour. An enormous literature in psychology and economics discusses what drives people to give. There is considerable evidence that the main driver of giving or helping behaviour is an emotion like empathy or sympathy or compassion (see, e.g., Coke et al., 1978; Reference Eisenberg and MillerEisenberg & Miller, 1987). The extent to which these emotions are felt depends on a number of factors, including one’s own personal state, past experience, proximity, similarity and vividness (Reference Loewenstein and SmallLoewenstein & Small, 2007), e.g., emotional arousal (empathy and distress) is higher when attention is drawn to single, identified victims and donation requests of this type elicit considerably more contributions than requests for a more general cause, disease or catastrophe affecting many people (see e.g., Reference Small and LoewensteinSmall & Loewenstein, 2003; Reference Kogut and RitovKogut & Ritov, 2005a, 2005b, 2007; Reference Small, Loewenstein and SlovicSmall et al., 2007).

There is, however, debate (e.g., Reference Batson, Batson, Griffit, Barrientos, Brandt, Sprengelmeyer and BaylyBatson et al., 1989) about the potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between empathy and giving and in particular about whether the ultimate motive for giving is purely altruistic or egoistic. Do people give simply because they want to increase the welfare of others or do they give in order to gain rewards or avoid punishments?

Batson and his co-authors (e.g., Reference Batson, Batson, Griffit, Barrientos, Brandt, Sprengelmeyer and BaylyBatson et al., 1989) make the case for pure altruism and claim that prosocial behaviour resulting from empathy is directed towards the benefit of those one feels empathy for rather than only towards obtaining rewards (praise, pride) or avoiding punishments (guilt, shame).

Reference CollardCollard (1978) and Cialdini and his co-authors (see e.g., Cialdini et al., 1973; Reference Cialdini and KenrickCialdini & Kenrick, 1976; Reference Cialdini, Kenrick, Baumann and Eisenberg-BergCialdini et al., 1982; Reference Kenrick, Baumann and CialdiniKenrick et al. 1979), are firmly in the egoistic camp, arguing that the ultimate goal of giving is only benefit to the self. Such benefit arises in the following forms:

-

1. Alleviating aversive arousal: Cialdini et al. (1973) propose a negative state relief model of helping: empathy or compassion increases sadness and it is the egoistic desire to relieve sadness which motivates helping. Helping is thus instrumental to restoring mood (see also Cialdini et al., 1982; Reference Rosenhan, Karylowski, Salovey, Hargis, Rushton and SorrentinoRosenhan et al., 1981; Reference Baumann, Cialdini and KenrickBaumann et al., 1981; Reference Manucia, Baumann and CialdiniManucia et al., 1984). In Reference Cialdini, Schaller, Houlihan, Arps and FultzCialdini et al.’s (1987) Experiment 1 high empathy subjects help more except when they had received a sadness-cancelling reward. In their Experiment 2, high empathy subjects who were given a placebo mood fixing drug (which made them believe their sad mood could not be alleviated by helping) did not help more than low empathy subjects. However, Reference BatsonBatson (1990) points to a body of evidence suggesting that high empathy subjects will offer high levels of help even when escape is easy.

-

2. Anticipating feeling good about oneself (maintaining or enhancing self-image) or avoiding feeling bad (guilt): Reference AndreoniAndreoni (1989, 1990, 2001) has written extensively about the psychological benefits (warm glow) associated with giving. Using survey data from 136 countries, Reference Aknin, Barrington-Leigh, Dunn, Helliwell, Biswas-Diener, Kemeza, Nyende, Ashton-James and NortonAknin et al. (2010) show that prosocial spending universally leads to emotional benefits for donors. Reference Konow and EarleyKonow and Earley (2008) find a correlation between happiness and generosity—dictators who share experience more long run happiness and happy subjects are more likely to share—but conclude that psychological well being is the primary cause of both happiness and dictator generosity. In an experiment designed to disentangle causality, Dunn et al. (2008) find that students randomly assigned to spend money on others are significantly happier than those assigned to spend money on themselves.

-

3. Anticipating receiving social rewards or avoiding social punishments: If prosocial behaviour (or the lack thereof) is publicly observed, social considerations such as gaining prestige (Reference HarbaughHarbaugh, 1998; Reference Ariely, Bracha and MeierAriely et al., 2009) or avoiding shame may matter. Individuals with higher social desirability concerns help more. Altruism can be instrumental in signalling wealth or status (see e.g., Reference BeckerBecker, 1974; Reference Glazer and KonradGlazer & Konrad, 1996; Reference Griskevicius, Tybur, Sundie, Cialdini, Miller and KenrickGriskevicius et al., 2007). There is ample evidence that peer pressure or even the mere knowledge that others are contributing increases contributions (see e.g., Reference Andreoni and ScholzCialdini, 1984). Showing prospective donors a (fictitious) list of previous donors increases compliance and donations (Reference ReingenReingen, 1978). Several field experiments have shown that contributions to public goods or charity can be manipulated by providing participants with information on others’ contributions (see, e.g., Reference Shang and CrosonShang & Croson, 2009, on donations to a public radio station and Reference Frey and MeierFrey & Meier, 2004, on charity donations). The presence of peers can have a strong influence on the choice between selfish and selfless behaviour. Reference Andreoni and ScholzAndreoni and Scholz (1998) find that neighbours’ (defined by socio-demographic space) donations have a measurable effect on household giving. Reference Andreoni and PetrieAndreoni and Petrie (2004) and Reference Rege and TelleRege and Telle (2004) find that unmasking subjects and their donations in a public good game significantly increases contributions. In a field experiment at a Costa Rican national park, Alpizar et al. (2008) find that voluntary contributions in public in front of the solicitor are 25% higher than those made in private. Image concerns may be particularly salient if the observer of one’s generosity (or lack thereof) is an acquaintance or a friend. Reference MeerMeer (2009) finds that both the decision to give and the amount donated are affected by the existence of social ties and shared characteristics between the solicitor and the donor. Reference Reinstein and RienerReinstein and Riener (2012) show that even a superficial acquaintance can significantly affect donation decisions. In a similar experimental setup to ours, participants could choose to give some, all, or none of their endowment to a real charity. The experiment started with a meet and greet session among participants. Leaders (first movers) and followers (second movers) are observed in a range of anonymity scenarios. When a leader’s donation and identity are revealed to the follower, the follower’s donation increases directly with the leader’s. When the donation is revealed without the leader’s identity, however, no such impact is observed. Reference Mujcic and FrijtersMujcic and Frijters (2011) find that car commuters act more selfishly when they are alone and display greater altruistic behavior when passengers are present. This, however, could be due to the two groups having different personality traits: those in cars with passengers may be intrinsically more altruistic than those travelling alone. This type of issue highlights the role of controlled experiments in this field. There is a psychology literature which shows that even a very minimal social cue such as watching eyes (three dots in the configuration of a simple face) has a positive effect on giving. In Reference Haley and FesslerHaley and Fessler’s (2005) dictator games, if the computer screen displays stylized eye spots, twice as many subjects give than in the control group (see also Reference Rigdon, Ishii, Watabe and KitayamaRigdon et al., 2009; Bateson et al., 2006 and Reference Burnham and HareBurnham & Hare, 2007).

The contribution of our paper is as follows. In line with the literature we find strong evidence of peer effects and the impact of social desirability concerns. We also find that more generous donors are happier with their donation decision. Our focus is however on how donors’ happiness with their decision is affected by peer pressure.

Some recent literature discusses avoidance of giving. Several studies use exit options in a dictator game to illustrate such avoidance. Dana et al.‘s (2006) subjects are offered a choice between a $10 dictator game and a $9 exit option (if exit is chosen the recipient does not find out about the game). Rational subjects should demand at least $10 to exit but a substantial fraction of subjects (about one third) choose to exit at $9. Broberg et al. (2007) find that the mean exit reservation price equals 82% of the dictator’s endowment. Again, only about one third of subjects demand the full endowment or more to exit. Lazear et al. (2012) find that when forced to play a dictator game, over 60% of subjects share but when offered the option to avoid the game altogether (without the potential recipient finding out) less than a quarter of subjects share. These findings suggest that (some) people feel uncomfortable about being asked to give and are prepared to forego payoffs to avoid being in that situation. Making a choice of how much to give may be considered uncomfortable. The anticipation of discomfort with any resulting inequality may be unpleasant. Yet another explanation is that subjects know they would give too much.

The study most closely related to our work is Della Vigna et al.’s (2012) field study which investigates the effect of door-to-door solicitation on donors’ welfare. They vary the extent to which households are made aware of a forthcoming fundraising drive. Some households receive a flyer informing them of the exact time of solicitation (thereby allowing them to avoid solicitation), others are also provided with an “opt out” box if they don’t want to be solicited, and a control group is approached in the usual way without any prior warning in the form of a flyer. A significant proportion of warned households do not answer the door and also (when possible) check the box requesting no solicitation. The findings also suggest that those who ticked the “do not disturb” box would have made a small contribution in the absence of a warning about solicitation.

A recent newspaper article, Footnote 1 entitled “Stop asking me for charity money!”, contains the following quotes, which illustrate how some people feel about sponsorship and donation requests:

“I hate being made to feel as though I don’t care if I don’t respond to my friends’ requests for sponsorship.”

“…who gives £2 once they are on the online pledge page and see everyone else’s gift of a tenner or more?”

“I hate it when my friends ask me to donate.”

“Please don’t lay a guilt trip about it on me just to get me to sponsor you.”

“I ended up donating money I could ill afford.”

Clearly not everyone gives to charity freely, and, whilst we don’t wish to claim that other motivations don’t play an important role, we argue that peer pressure is effective in generating donations but those donations may reflect reluctant altruism.

2 Experimental design

We recruited 211 students at the London School of Economics via email, inviting them to take part in a short survey in return for £10. As part of the survey, subjects were asked whether they wished to donate any of their newly earned cash to charity. The questionnaire contained a list of five charities (Oxfam, Cancer Research, Red Cross, Demelza and RSPCA) along with a brief description of each charity. Subjects selected one charity and could choose to donate £1, £2,…, £10.

The survey was relatively short and consisted of a brief set of demographic details along with a personality questionnaire. We also asked subjects how much money they had donated to charity in the last year. Subjects indicated their level of agreement with the statement “I care about what others think of me”, which we used to measure image concern. In addition, subjects were asked to guess the average donation in the experiment. They were told that the person making the most accurate guess of the average donation would win a prize (a £50 Amazon voucher). The guess of others’ donations was made prior to subjects’ own donation decision.

At the time of recruitment, subjects were given a time slot. Subjects were randomly allocated to individual and pair time slots. There were 108 subjects (54 pairs) in the treatment group and 103 subjects in the control group. Subjects in the control group were asked to make their donation decision on their own while those in the pair treatment made two donation decisions. Before making their initial donation decision, individuals in the pair treatment were instructed that their donation decision would be revealed to their partner. After they made their donation decision privately, they were given two minutes to discuss their decision. They then had the opportunity to revise their donation decision. They were informed that their final decision would again be revealed to their partner. Although pairs were told at the start of the survey that their donation decision would be revealed to their partner, they were not aware that they would be given the opportunity to revise their donation decision.

Pairs and individuals were given fifteen minutes to complete the survey. Pair members sat in the same room to fill out the survey but did so privately (the only time subjects were allowed to communicate was during the pairs discussion period). Subjects in the control group completed the survey privately in a room without any other participants.

Once they had made their donation decision, all subjects were asked how happy they were with their choice (for the treatment group this was asked twice: once after the first donation decision, but before the discussion, and once after the second donation decision).

After filling out the survey, subjects were paid the amount they had decided to keep.

3 Results

3.1 Treatment effect

3.1.1 Pair donations are larger than control group donations

Paired subjects’ mean first round donation is significantly higher than the control group average. On average, pair subjects donate £3.64 while control group subjects donate £2.55 (p=0.02).Footnote 2

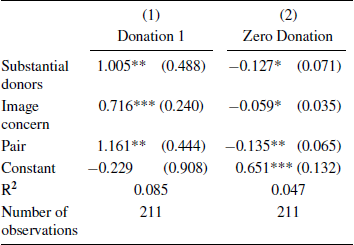

In Table 1, column (1), the dependent variable, Donation 1, represents the first round donation decision of paired subjects and the only donation decision of control group subjects. We asked subjects to state the amount they had donated to charity in the last year. Out of 211 participants, 47 reported having donated £0, 103 donated between £0 and £50, and 61 donated £50 or more. We will refer to the last category as substantial donors. Footnote 3 Image concern indicates the level of agreement (5 point Likert scale) with the statement “I care about what others think of me”. Pair is a dummy variable indicating whether the subject is in the treatment group. Note that the effect of pair is also significant by a simple t test (p=.02).

Table 1: Regression results for Donation 1 and Zero Donation. Coefficients are unstandardized.

Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively. Coefficients in column (2) are based on ordinary regression, but the results are similar for probit regression.

Substantial donors give significantly (£1) more than others. Image concern has a significant and large effect on donation. Paired subjects give significantly more (£1.16) controlling for image concern and whether they are subtantial donors.

3.1.2 Fewer zero donations in pairs

The treatment effect is largely due to a significantly lower proportion of zero donations in the pair treatment. Footnote 4 Overall, 72 subjects out of 211 donated £0. Out of 103 people in the control group, 42 donated £0 (41%), and out of 108 paired subjects, 30 donated £0 (28%).

As can be seen in Table 1, column (2), substantial donors are 13% less likely to donate zero. Paired subjects are significantly (13%) less likely to donate zero controlling for whether they are substantial donors and image concern.

The finding of fewer non-donors in the pair treatment is consistent with Dickert et al. (2011), who in their two stage processing model of donations, argue that mood management motivation is important in the decision whether to donate or not whereas the actual amount donated depends on more altruistic empathy feelings. Genuine altruism or empathy (which affects amount donated) can be assumed to be equal in both groups of subjects. However, mood management differs between the two groups. Paired subjects may have anticipated more shame if they did not donate.

Although Table 1 provides evidence for the treatment effect, the explanatory power of the models for donation and zero donation is low. Clearly, participation in charitable giving and the level of donations is affected by a number of variables not included in this study. Reference Jones and PosnettJones and Posnett (1991), for example, find that household participation in charitable giving depends on income, education, house tenure and region whereas the level of donation depends mainly on income.

3.1.3 False consensus effect

Reference Frey and MeierFrey and Meier (2004) discuss the false consensus phenomenon (e.g., Ross et al., 1976) in the context of charity donations: individual preferences regarding contribution may influence expectations about pro-social behaviour of others, and vice versa, beliefs about how much others contribute can affect subjects’ donations. Footnote 5 We asked subjects to guess the average donation made by participants in this study prior to making their own donation decision. We found a high correlation between subjects’ guesses and their own donations (0.54, p<0.001). Our subjects anticipated the treatment effect in the sense that those in pairs guessed significantly higher than those in the control group (£4.37 versus £3.64, p=0.03). Both groups over-estimated their peers’ generosity: 55% of subjects donated less than their guess and the average guess (£4) was significantly (p<0.001) higher than the actual mean donation level (£3), so, on average, subjects must think that they are less generous than others. This finding is in contrast with Muehleman et al. (1976) and Reference Kogut and Beyth-MaromKogut and Beyth-Marom (2008), who find that subjects consider themselves more generous than their peers. However, in these studies participants were asked hypothetical questions about their own and other’s inclination to help whereas in our study subjects had to decide to actually help or not. Abstract stimuli may be more likely than concrete situations to generate a better than average effect.

3.2 Peer effect

3.2.1 Effect of partner’s first round donation on second round donation

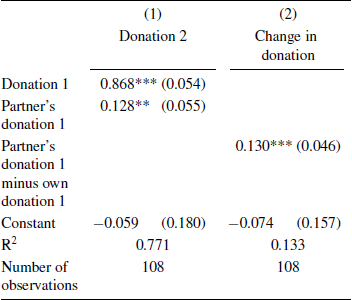

In Table 2, column (1), Donation 2 is the second round donation of paired subjects. Donation 1 is their first round donation and Partner’s donation 1 is their partner’s first round donation. Partner’s first round donation has a significant impact on second round donation. Not surprisingly, first round donation has a strong effect on second round donation.

Table 2: Regression results for Donation 2.

Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

In column (2) we regress change in donation between second and first round on the difference between own and partner donation in the first round. Being paired with a more generous donor significantly increases second round donations.

3.2.2 Change in donations

The change from first donation to second donation ranged from −£10 to +£5. A large majority of subjects (78%) did not change their donation decision at all. Out of 54 pairs, in 32 pairs neither subject changed their donation decision, in 20 pairs one changed and in 2 pairs both changed. Subjects whose partners donated more than them in the first round significantly increased their donation by £0.55 on average. And subjects whose partners donated less than them in the first round significantly decrease their donation by £0.72. In the 7 pairs where subjects’ first round donations were equal, neither subject changed his or her donation decision. Out of the 47 subjects whose partners’ first round donation exceeds theirs, only one changed to a lower donation, and, similarly, only one out of the 47 subjects whose partner’s first round donation was below their own changed to a higher level of donation.

3.2.3 The extreme subjects

It is well known that individuals tend to conform to a social norm even when their preferences are heterogeneous but agents with sufficiently extreme preferences tend not to conform (Reference BernheimBernheim 1994): subjects at the extreme (choosing to donate either £0 or £10 in the first round) were less likely to change their donation decisions than subjects who were not extreme (donating between £0 and £10 in the first round). 89% of the extreme donors did not change versus 70% of the non-extreme donors (p=0.02). This effect is in line with Reference Frey and MeierFrey and Meier’s (2004) findings. In their study, individuals who have donated on some occasions and not on other occasions are labelled as indifferent. These are the people who are most likely to change their behaviour. Those who never contributed do not change their behaviour, while those who are indifferent react most strongly to information on others’ behaviour. A similar result is found in Reference Andreoni and PetrieAndreoni and Petrie (2004) who discuss fundraisers’ intuition that there are three groups of people—those who never contribute, those who always contribute and those who can be persuaded by social pressure.

3.3 Happiness with donation decisions

Our subjects were generally happier with their donation decision, the higher the amount donated, but those in pairs were significantly less happy with their donation decision when controlling for amount donated. We know that paired subjects donated more. The fact that they are unhappier with their donation decision suggests that subjects in pairs may have felt coerced to donate more than they would have in the absence of a peer.

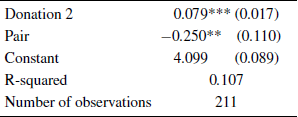

In Table 3, column (1), the dependent variable, Happy, represents the level of agreement (5 point Likert scale) with the statement “I am happy with my donation decision”. For pairs, it refers to their response after their final decision. Donation 2 refers to the only donation decision for the control group and the second donation decision for paired subjects. Donation has a significant, positive effect on happiness levels. But paired subjects feel significantly less happy with their decision, controlling for donation. (The difference without the control for donation was in the same direction but not significant.)

Table 3: Regression results for Happy.

Standard errors are reported in parentheses. *, **, *** indicates significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively.

4 Conclusion

In our experiment, subjects donate an amount up to £10 (their show-up fee). One group of subjects donates on their own (control group) and another group of paired subjects makes a final (second) donation decision after conferring with their partner and revealing their own initial donation decision (treatment group). Before making their initial donation decision, subjects in the pair treatment are aware that their donation decision will be revealed to their partner. We find a significant pure treatment effect: paired subjects’ mean first round donation is significantly higher than the control group average. On average, pair subjects donate £3.64 whereas control group subjects donate £2.55. This treatment effect is largely due to a significantly lower proportion of zero donations in the pair treatment. This latter finding ties in with Dickert et al.’s (2011) two stage model of charitable donating: the decision whether to donate (as opposed to the second stage decision of how much to donate) is driven by mood management. In the pair treatment, subjects are exposed to shame if they do not donate, hence a higher proportion makes a positive donation.

Within the treatment group of pairs we observe significant peer effects which result in some convergence of pair donation decisions. Each subject in a pair makes two donation decisions, one before conferring with his partner and one after. In the pairs where first round donations are equal, neither subject changes his donation decision. In the other pairs, subjects, on average, move their donation decision towards their partner’s. Reference Andreoni and PetrieAndreoni and Petrie (2004) report convergence of contributions in a repeated public good game. Presence of leaders (high contributions) increases and presence of laggards (low contributions) decreases other group members’ contributions. Such conditional cooperation is extensively explored in the literature on contributions to public goods, and is related to peer effects in charitable giving. There is a subtle difference however: in public goods experiments, subjects stand to potentially gain from the common public good if they contribute, so they may contribute because they do not want to be seen to be a free rider. In charitable giving experiments, in contrast, subjects do not directly benefit from donations and hence there is no free rider stigma.

We also found heterogeneity in peer pressure effects: extreme donors (those who donated nothing and those who donated all of their endowment) are less susceptible to peer pressure, they are less likely to change their donations.

The final part of our analysis is concerned with the “happiness” associated with subjects’ donation decisions. In particular, we investigate whether the increase in donations due to peer pressure is accompanied by lower comfort levels of the (more generous) paired donors. Subjects are generally happier with their donation decision the higher the amount they donate but those in pairs are significantly less happy with their donation decision controlling for amount donated. This result suggests that subjects in pairs may have felt coerced to donate more than they would have in the absence of a peer, a sign of “reluctant altruism”.

In our experiment, the extent to which subjects care about what others think of them affects donations. The focus of our paper is however not the existence of social image or peer effects, although we find strong evidence of both of these effects. The contribution of our paper is the investigation of subjects’ comfort levels with their donation decisions in the presence of peer pressure. If people give more due to social influence, does that make them more or less happy with their donations? Peer effects in charitable giving may arise from lack of information needed to make decisions. Information from peers may be important when deciding how much to give and whether to give, especially if subjects are unaware of any norm. However, if the main effect of peer presence is provision of information then subjects should be more comfortable with their donation decisions when they have received such information. Our result that paired subjects are less happy with their decision indicates that information provision is not the main driver of peer effects in charitable giving.

Peer pressure has a significant effect on giving behaviour. Merely increasing the number of observers from one (the experimenter) to two (the experimenter and a peer) increases donations by over 40%. It is not surprising that giving websites which exploit peer pressure effects are popular. Our results suggest that a good strategy for street fundraisers (chuggers) is to approach pairs rather than single pedestrians. Pairs may feel more social pressure to stop and donate. Individuals raising money via sponsorship forms or giving webpages may find it easier to raise money by, say, approaching friends in groups. However, our findings represent a health warning in this context: pressure leads to increased donations but it reduces donors’ comfort levels. Potential giving website customers may want to ask themselves whether they care enough about their charitable cause to compensate for the unease inflicted on their friends.

Although peer pressure is effective in generating donations, charities might want to consider the longer term effects of using peer pressure strategies. We found that donors who give more due to peer pressure are less happy about their donation. In addition, it is possible that a donor who rationalises his donation decision as instrumental in avoiding shame will not attribute his giving behaviour to caring about the cause. Footnote 6 Both of these phenomena make future donations less likely.

Whilst capturing some essential features of giving websites, our experimental design does not mimic that environment perfectly. Our paired subjects are publicly invited to donate, whereas on a giving site there is no evidence of who received a request, although a fundraiser could make this information public by sending the invitation to donate on the site in a mass email revealing the identity of all potential donors. It would be interesting to see whether donations can be increased by having public lists of potential donors on the webpage with their donations initially set at zero.

A possible extension of our study is to look at the effect of peer pressure in larger groups. We found some evidence of a desire to conform in our paired subjects. It would be interesting to examine these dynamics in larger groups. Increased heterogeneity in groups may reduce pressure to conform but being observed by several peers may increase it. The effect of a larger number of subjects on donation levels would be of interest in itself. Various possible motives could be present to generate a higher level of donations but there is a possibility that donations would decrease in larger groups if subjects feel that their own contribution is less significant as in the bystander effect.