1 Introduction

Reference Ekman, Matsumoto, Friesen, Ekman and RosenbergScott, Inbar and Rozin (2016) (hereafter, SIR) presented evidence that trait disgust underlies opposition to genetically modified foods (GMFs). We (Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman, Cusimano & Leeman, 2017) disputed their claim on the basis that SIR did not appropriately measure trait disgust (disgust qua oral inhibition or OI)Footnote 1 and that, once measured appropriately, it appears to play no role in people’s opposition to GMF. Instead we found that sensitivity to a potential/uncertain threat (as gauged by feelings of creepiness in response to a variety of “unpleasant” scenarios comprising the 7-item pathogen sub-scale [TDDS-P] [Reference Fessler, Arguello, Mekdara and MaciasTybur, Lieberman & Griskevicius, 2009]) was the best affective predictor of judgments regarding GMF. Reference Inbar and ScottInbar and Scott (2018) (hereafter, IS) have taken issue with our paper on many grounds. In most cases we believe their criticism misses the mark. In this paper, we lay out our rationale why and present additional empirical evidence that bears on the new findings that IS report. Though this response is a critique, we believe that Inbar, Rozin and Scott have raised some thought-provoking points and we would welcome the opportunity to explore them collaboratively in the future. We begin by reviewing our key objections to SIR and what we have done to address them.

2 Objections to SIR and an overview of Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al. (2017)

SIR reported an association between subjects’ responses to the Disgust-Sensitivity Scale – Revised (DS-R, Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk, Lohr and ElwoodOlatunji et al., 2007), a refined variant of Reference Haidt, McCauley and RozinHaidt et al.’s (1994) trait disgust sensitivity scale, and their opposition toward GMF. This scale has been criticized for its content as well as its response options (e.g., Landy & Piazza, 2017; Reference Fessler, Arguello, Mekdara and MaciasTybur et al., 2009). Regarding the former, the majority of vignettes describe situations that could be interpreted as physically disgusting, but also creepy, irritating, frightening, surprising, or upsetting. Regarding the latter, only a subset of items (vignettes) ask participants to report how “disgusting” they find a situation or event, with the remaining items’ response options covering a wide range of negative states, including “bothered”, “upset”, and other non-specific expressions of avoidance. Exacerbating these issues, the meaning of “disgusting” itself has been has been shown to be broad enough to encompass a gamut of affective reactions (e.g., Landy & Piazza, 2017; Reference NabiNabi, 2002; Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman et al., 2017), making it the denotative equivalent of “bothered”. Given the multi-faceted nature of the DS-R, one would be hard pressed to see it as anything more specific than a measure of negative affect (with emphasis on creepiness, horror, disapproval, and disgust).

Our study was, in part, designed to ask if disgust sensitivity would still predict attitudes toward GMF when we could be more certain that we were measuring actual feelings of disgust. To address the limitations of the DS-R, we used a set of vignettes that are more pathogen-specific (TDDS-P, Reference Tybur, Lieberman and GriskeviciusTybur et al., 2009) as well as a 3-item measure of disgust as oral inhibition (OI), a measure derived from the theoretical meaning of disgust (Reference NabiNabi, 2002; Reference Royzman, Leeman and SabiniRoyzman, Leeman & Sabini, 2008; see below). Prior studies have shown OI (unlike “disgust”Footnote 2) to be specific to pathogen-linked content (Reference Royzman, Atanasov, Landy, Parks and GeptyRoyzman, Atanasov, Landy, Parks & Gepty, 2014; Reference Blake, Yih, Zhao, Sung and Harmon-JonesBlake, Yih, Zhao, Sung & Harmon-Jones, 2016), unrelated to social desirability concerns (Reference Royzman, Kim and LeemanRoyzman, Kim & Leeman, 2015), and resistant to figurative use (Reference Royzman, Leeman and SabiniRoyzman et al., 2008). We also included a set of concretely phrased non-disgust options that made it possible to isolate OI from some pertinent alternative reactions (e.g., social disapproval or unpleasant non-gustatory sensations). The inclusion of specific non-disgust options is a significant improvement for two reasons. First, including distinct alternative response options undercuts any motivation for a subject to use OI to express some other feeling that they may have or misreport what they feel in the interest of signaling that they have had some feelings at all. Second, it allows one to test whether any of these other affective reactions may have driven the original reported association between “disgust” and GMF attitudes. Our study was also an improvement in terms of scale administration (see Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al., 2017, p. 467, for a summary).

With these refinements in place, the correlation between oral inhibition and people’s attitudes to GM-food was close to zero. A subsequent analysis showed that OI was not predictive of GMF attitudes either as a composite or at the level of its constituent responses (all ps> 0.4). Thus, contrary to the claims made by SIR, disgust-the-feeling (OI) appears to be unrelated to a desire to restrict GM-food (harms and benefits not withstanding). Notably, disgust-the-word (“disgusting”) still did rather well, serving as a significant predictor of opposition to GM-food (r = .25, p = .004), just as it did in SIR’s original study.

In spite of these deflationary results, Inbar and Scott make no attempt to defend their approach. Thus, it appears that what ultimately divides us is not the question of whether DS-R can be retained or salvaged as a measure of trait disgust but whether our approach offered enough of an improvement over SIR’s to make our findings more trustworthy.

IS advance four major reasons why they do not view our study as an improvement. First, they express a concern about our lack of proper psychometric analyses, thereby calling into question whether our novel high-granularity response options did in fact carve out distinct affective categories. Second, and most fundamentally, they assert that OI is incidental to the modern construal of disgust and therefore that we were unjustified using OI to operationalize disgust. Third, they argue that it is particularly inappropriate to pair OI with TDDS-P since it is characterized by lack of “oral” items. And fourth, they question the lay meaning of “creeped out” in the context of the TDDS-P vignettes. Finally, in their response, IS offer new evidence purporting to bolster their claim that disgust is the predominant feeling in reaction to thinking about GMF. We address each of these issues in turn.

3 Have we measured distinct affective categories?

One of Inbar and Scott’s central critiques is that we are not justified to assume that our scale of concrete, high-granularity options (e.g., “feel like gagging”) in fact measured separate affective categories (e.g., distinguishing oral inhibition from non-gustatory aversive sensations or moral disapproval).

In developing this critique, Inbar and Scott state early on that confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is not appropriate for the three single-item factors in the measure because CFA requires a minimum of two (but preferably three) indicators for each latent factor (Reference BentlerBrown, 2006). This is a valid point, but the issue is broader than that. Factor analysis in general (not only CFA but including exploratory factor analysis), is considered inappropriate for factors with less than two items (Reference Costello and OsborneCostello and Osborne, 2005). As a result, the full 11-item measure utilized by Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al. (2017) is not appropriate for inclusion in any type of factor analysis since it was designed to include multiple single-item factors. Thus, the exploratory factor analysis conducted and reported by Inbar and Scott was inappropriate on statistical grounds.

CFA is relevant to our measure because it was based on established scales, and items were grouped a priori according to presupposed factors based on theory, prior findings, and face validity (Reference BentlerBrown 2006). Thus, for each of the seven vignettes we conducted CFA for the three putative factors that included at least two indicator variables. This yielded a total of 8 items per vignette: the three oral inhibition items, the three disapproval items, and the two epidermal discomfort items.

The model fit indices included (among others): chi-square (Reference HatcherHatcher, 1994), the SRMR (Reference Hu and BentlerHu & Bentler, 1999), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Reference BentlerBentler, 1990), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Reference Brown, Cudeck, Bollen and LongBrown & Cudeck, 1993).Footnote 3 These indices indicated excellent fit of the data to the proposed model structure. For example, chi-square was statistically significant for 6 of the 7 vignettes with the “poop” vignette being the only one with a significant chi-square value. (Notably, chi-square is often significant even in cases when a model provides an acceptable fit to the data [Reference Floyd and WidamanFloyd & Widaman, 1995; Reference HatcherHatcher, 1994]). CFI values were greater than .95 for all seven vignettes and SRMR values were less than .08 for all seven vignettes. RMSEA was less than .08 for six vignettes with the other coming in under the .10 value that is considered acceptable. Additional indices were equally consistent with the model (contact authors for further details).

In summary, the single item factors included in the measure are not appropriate for any form of factor analysis. This is indeed an inherent limitation to the use of single item factors, however these items included in Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al. (2017) were highly face valid. CFAs conducted with the remaining response options indicated excellent model fit for each of the seven vignettes measured. These results support a conclusion that the measure utilized in Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al. (2017) was not psychometrically unsound as argued.

4 Is oral inhibition an appropriate measure of disgust?

IS’s most pivotal critique is that there is a clear scientific consensus that oral inhibition is not a theoretically appropriate conceptualization of disgust. If they are correct, then our failure to observe an association between oral inhibition and GM attitudes has no significant bearing on their claim that feelings of disgust affect GM attitudes. However, it appears that IS are mistaken about the current consensus among disgust scholars.

From Darwin on, scholars viewed disgust as a category of food rejection (e.g., Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Lewis and HavilandRozin, Haidt & McCauley, 1993; Reference Olatunji and SawchukOluatunji & Sawchuck, 2005), whose origin is the “mammalian bitter taste rejection system” (Reference Rozin, Haidt and FincherRozin, Haidt & Fincher, 2009, p. 1180), and whose facial emblem is the “gape” (Reference Rozin, Lowery and EbertRozin, Lowery & Ebert, 1994) or the “sick face” (Reference Widen, Pochedly, Pieloch and RussellWiden, Pochedly, Pieloch & Russell, 2013). Rozin views disgust as “a food-related emotion” defined as “revulsion at the prospect of oral incorporation of offensive objects” (Reference Rozin and FallonRozin & Fallon, 1987, p. 23; Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Levinson, Ponzetti and JorgensonRozin, Haidt & McCauley, 2000) and affirms that all the classic disgust “scholars, as well as most others, posit a special relation between disgust and the mouth, and disgust and food rejection” (Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Levinson, Ponzetti and JorgensonRozin et al., 2000, p. 188). Reference Haidt, McCauley and RozinHaidt et al. (1994), whose trait disgust scale is the precursor to the DS-R (Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk, Lohr and ElwoodOlatunji et al., 2007), stipulate that disgust is “at its core, an oral defense” (p. 702) while Olatunji & Sawchuck describe it as a manner of food rejection and a “guardian of the mouth” (Reference Olatunji and SawchukOluatunji & Sawchuck, 2005, p. 935). Reference EkmanEkman (2003) explicitly linked disgust with gagging (see also Reference Ekman, Matsumoto, Friesen, Ekman and RosenbergEkman, Matsumoto & Friesen, 2005). Thus, in an influential research report designed to unknot the more pointed theoretical meaning of disgust from the rougher lay meaning of the term, Reference NabiNabi (2002) affirms that, though disgust’s broad “common usage … appears to reflect that which is not only repellent but also irritating or annoying” (Reference NabiNabi, 2002, p. 695), “theoretically, disgust refers to the offence taken to noxious objects or ideas that evoke…nausea” (Reference NabiNabi, 2002, p. 695) (see also Reference Kayyal, Pochedly, McCarthy and RussellKayyal, Pochedly, McCarthy & Russell, 2015; Reference Royzman and SabiniRoyzman & Sabini, 2001).

Most importantly, oral inhibition emerges as the criterial feature of disgust that contemporary scholars reach for when in need of a clear touchstone to separate disgust from non-disgust. Reference NabiNabi (2002) used a desire to vomit (“feel like throwing up”) as a key criterion for establishing if the lay terms “disgusted/“disgust” brought to mind what was mainly disgust or some mix of annoyance and anger. In an analysis seeking to differentiate disgust from a related parasite avoidance adaptation, Reference Kupfer and FesslerKupfer and Fessler (2018) delineate the experience of being disgusted as involving “feelings of revulsion, nausea, gagging, the urge to vomit”. In arguing that Nazis are genuinely disgusting, Reference Sherman, Haidt and CoanSherman, Haidt and Coan (2007) aimed to show that people watching a video about the neo-Nazi culture reported the tightening and clenching of their throats. In claiming that fraud and dishonesty provoke actual disgust, Reference Chan, Boven, Andrade and ArielyChan, Boven, Andrade and Ariely (2014) sought to demonstrate that being exposed to instances of deceit reduces oral consumption of water or milk. And, as part of the project aiming to produce a highly discriminant facial display of disgust, one that would clearly differentiate it from anger, sadness, or fear, Widen et al. (2014) instructed an actress to imagine that she was feeling sick and was about to vomit (with the resultant “sick face” being highly similar to the “gape” face used by SIR).

Some scholars have also forewarned of the dangers of linking disgust with something as non-criterial as avoidance since, unlike OI, it would result in difficulties demarcating it from states such as “fear” (e.g., at spiders and gore; Reference Cisler, Olatunji and LohrCisler, Olatunji & Lohr, 2009; Reference Woody and TeachmanWoody & Teachman, 2000), which people also experience when exposed to pathogen vectors. In the case of a self-report measure such as the TDDS-P, operationalizing disgust as avoidance (e.g. “rate the degree to which this [bleeding cut] makes you want to move away”) would make it nearly impossible to separate it from a medley of other affective states (fear, creepiness, epidermal discomfort, disapproval) which TDDS-P is well capable of invoking (Landy & Piazza, 2017; Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman et al., 2017).

The current scientific consensus is hard to miss. Oral inhibition is what scholars uniformly appeal to when the goal is isolate the criterial feature(s) of disgust, be it for the purpose of segregating the specific theoretical meaning from a broader lay one, differentiating disgust from a closely related non-disgust response, establishing that a non-prototypical disgust stimulus (e.g., Nazis, fraudsters) is genuinely disgusting, developing a discriminant non-verbal operationalization of disgust, or ascertaining cases of disgust-specific avoidance in a clinical setting. Any non-OI delineation of disgust is thus likely to be a minority position.

What about the authors that IS cite? Could they be the dissenting minority in question? The answer appears to be no. To the degree that these authors take a stab at delineating the disgust experience at all, all appear to endorse OI as the key component of that experience. Reference Tybur, Lieberman and GriskeviciusTybur et al. (2009) list “sensation of disgust” and “disgust facial expression” as the two primary features of the output of the “disgust system” (p. 69) and suggest that disgust is characteristically or “often accompanied by nausea, a desire to vomit, and a loss of appetite” (p. 70). Reference Cisler, Olatunji and LohrMurray and Schaller (2016) limit their comment on the “emotional experience” of disgust to an observation that said experience has “evolved from a more ancient and functionally specific distaste response to oral stimuli (Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Levinson, Ponzetti and JorgensonRozin et. al, 2000), and many contemporary conceptual accounts identify infectious diseases as the primary selective pressure underlying its evolution” (p. 83). Finally, according to Reference Curtis, de Barra and AungerCurtis, de Barra, and Aunger (2011):

Contact with disgust elicitors, real or imagined, is associated with (i) a characteristic facial expression that is recognizable across cultures, (ii) behaviour patterns that include withdrawal, distancing, stopping or dropping the object of disgust and shuddering, (iii) physiological changes including lowered blood pressure and galvanic skin response, recruitment of serotonin pathways, increased immune strength, and (iv) reports of negative affect including nausea. (p. 390; italicized text is what Inbar and Scott quote as support for their view; bold emphasis is ours).

The quote merits two observations. First, Curtis et al.’s goal is clearly not to define or specify the criterial feature(s) of disgust, but rather to describe some of its observable identifiers or “associates”, none of which are at odds with the conception of disgust as OI. But more importantly, there is little doubt that, in the context of self-report measures, the identifier or associate of greatest relevance is (iv), which specifies what disgust is as an affective state and features nausea front and center.

None of this is obviously to dispute that disgust is linked to pathogen avoidance. Reference Royzman and SabiniRoyzman and Sabini (2001) were among the earlier authors to characterize disgust as a system for minimizing toxin or pathogen exposure at the level of adaptive task description. However, they also noted that the aversive experience of OI is a good candidate response for motivating physical withdrawal. All in all, there is little doubt that the prevailing scientific consensus is squarely on the side of OI being the criterial feature of disgust. The authors that IS have appealed to are either a part of (or, at the very least, do not detract from) this broad consensus.

5 Is oral inhibition ill-suited for TDDS-P?

Even if OI comprised a defensible measure of disgust in general, it may not have been defensible in the context of TDDS-P. In IS’s view, OI is “a priori … a poor fit for these [TDDS-P] non-oral items” (Reference Inbar and ScottInbar & Scott, 2018, p. 5). They are not explicit about why this is an issue, but we have a hunch. When it comes to items featuring red sores, bleeding cuts, or scurrying insects, the key adaptive task seems to be that of avoiding a potential pathogen exposure by eschewing physical contact with its source. One could argue that gagging and pursing one’s lips would have little adaptive value; what one wants first and foremost is to put some distance between oneself and a potentially diseased entity. Thus, the argument goes, people may not have felt true oral inhibition in response to these items at all.

But if the major concern is a lack of variance due to a floor effect, this is a worry easy enough to dispel by looking at our data. We found that oral inhibition (tied with creeped out) was the strongest high-granularity response reported in reaction to the TDDS-P items (with OI’s coefficient of variance [0.42] being 20% higher than that of “disgusted” [0.23], which did predict resistance to GMF, in line with Reference Scott, Inbar and RozinScott et al. [2016]). We see no reason why this should be otherwise. Other than the “moldy leftovers” item and the scurrying cockroach item (see Reference van Huisvan Huis, 2017 on the evidence of insect consumption among early humans and through evolutionary history), at least three items in the TDDS-P feature explicit (body odor) or implied (sweaty palms, dog poop) malodorousness, one of the key inputs to the food rejection system (Reference Rozin, Lowery and EbertRozin et al., 1994)Footnote 4. This issue to the side, it is unclear why the “orality” of an item should matter in the first place. Congruent with the theory of preadaptation (i.e., the co-option of existing structures/systems for new use; Reference Rozin and FallonRozin & Fallon, 1987), there is plentiful evidence that oral inhibition is elicited by a range of “non-oral” items ranging from bodily fluids (Reference Royzman, Leeman and SabiniRoyzman et al., 2008, Pilot) and injuries (Reference Chapman, Kim, Susskind and AndersonChapman, Kim, Susskind & Anderson, 2009; Reference Royzman, Leeman and SabiniRoyzman et al., 2008, Pilot) to anomalous sex (Reference Royzman, Leeman and SabiniRoyzman et al., 2008; Studies 1 and 2; Reference Royzman, Atanasov, Landy, Parks and GeptyRoyzman et al., 2014). In sum, our use of the TDDS-P scale for eliciting oral inhibition is as well justified as the use of OI itself.

6 Taking stock

Let’s collect our results. IS critiqued OI as a theoretically appropriate way to conceptualize and operationalize disgust while also contending that it was a particularly poor match for the TDDS-P vignettes. Having reviewed IS’s arguments, we have concluded that (1) according to the prevailing scientific consensus, oral inhibition is the criterial feature of disgust, (2) has no clear alternative, and (3) is the only reliable way to demarcate disgust from other pathogen avoidance mechanisms (creepiness, epidermal discomfort, fear), at least in the context of a self-report measure à la TDDS-P. Furthermore, (4) the combined weight of theory and evidence strongly indicates that our use of the TDDS-P scale was appropriate for eliciting oral inhibition. Along with the psychometric evidence in the section above, our decision to use a wide range of additional affective response options (including some face valid single-factor response options) further engenders confidence that subjects used our measure as intended.

What can be said about the overall validity of our measure? In modern validity theory (Reference Newton and ShawNewton & Shaw, 2013), validity is not considered a property of the test, but of a particular interpretation of that test adopted for a given purpose and whether this interpretation is justified in light of the totality of evidence before us. The key interpretative move that undergirds all conclusions in Reference Royzman, Cusimano and LeemanRoyzman et al. (2017) is that, imperfect as our assessment might have been, it is a considerably better proxy for the feelings of disgust (as understood by the scientific community at large) and their relationship to GMF attitudes than SIR’s. Everything that has been said above — OI’s hard-to-argue status as the criterial feature of disgust, its apparent specificity, its psychometric differentiation from Disapproval and Epidermal Discomfort, its selective tracking of pathogen-linked content — makes the move well justified.

7 The meaning of “creeped out”

If disgust sensitivity, properly measured, does not predict GMF attitudes, why might disgust sensitivity, improperly measured, do so? We hypothesized that sensitivity to potential threats might have, among other things, confounded the relationship between improperly-measured disgust sensitivity and GMF attitudes. This hypothesis was supported by a correlation between GMF attitudes and feeling “creeped out” in response to the TDDS-P.

IS claim that, while “creeped out” may be associated with unease about a potential threat or riskFootnote 5, it is an open question if this is the meaning that subjects had in mind when rating the items of TDDS-P. Implied in this worry is the claim that (a) the canonical elicitors of creepiness (those that one would expect to loom large in a subject’s minds when queried about the meaning of “creepiness” as such) are categorically different from (b) the content of the TDDS-P vignettes. But is this borne out by the evidence? Reference McAndrew and KoehnkeMcAndrew and Koehnke (2016) conclude from their study that non-normative health and hygiene (e.g., being extremely thin or obese, having greasy hair or pale skin) are typical triggers of creepiness (see also Reference Watt, Maitland and GallagherWatt, Maitland, & Gallagher, 2017, for a convergent analysis). In light of this, it appears that the characteristic triggers of feeling creeped out are well represented in TDDS-P. Indeed, half of the TDDS-P items portray individuals with non-normative, unhealthy physical characteristics or poor hygiene, including “Sitting next to someone who has red sores on their arm.”, “Standing close to a person who has body odor.” “Shaking hands with a stranger with sweaty palms”, and “Accidentally touching a person’s bloody cut”.

Whatever “creeped out” may or may not mean in the context of TDDS-P, it clearly not a stand-in for oral inhibition, the construct that comprises the theoretical meaning of disgust. It is this construct that SIR and IS presumably would want to implicate, not merely as a trait predictor, but also as a state antecedent, of people’s avowed opposition to genetically engineering animals and plants. Thus, the strong correlation between “creeped out” and GMF attitudes should not be taken as evidence in favor of IS’s thesis.

8 State disgust

In the penultimate section of their commentary, Inbar and Scott present an empirical critique of what they perceive to be our theoretical counterpoint to their “disgust fuels the moral opposition” proposal, i.e., that “fear, not disgust, is the primary emotion associated with GM food opposition” (Reference Inbar and ScottInbar & Scott, 2018, p. 3). They offer no textual evidence for this claim. This is not surprising since we never made such a claim. Our paper was concerned with the experience of “creepiness” (which we explicitly and repeatedly set apart from that of “fear” both in the principal study and in the supplementary survey) as a proxy for trait sensitivity to a potential hazard or risk. Our claim that sensitivity or vigilance towards risks may underlie GMF opposition is not equivalent to the claim that fear is the dominant reaction to thinking about GMFs, nor that fear (or a related feeling) is a causal antecedent of GMF oppositionFootnote 6. Therefore, IS are largely correct that we do not show evidence in favor of the claim that state fear is the dominant reaction to GMFs, but this is because no such evidence has ever been searched for in the first place.

This misunderstanding to the side, we have no principled opposition to the view that disgust is the dominant affective reaction towards GMF. That said, we were skeptical of the evidence that IS and SIR presented defending this claim, and conducted a study to re-assess the prevalence of disgust as a reaction to GMF.

9 Study re-assessing the prevalence of state-disgust

We conducted a study (described in detail in the Appendix) geared to re-reassess the absolute and relative prevalence of state disgust when thinking about GMF. Both SIR and IS presented some studies to this effect. Our study departed from theirs in several ways. First, rather than presenting subjects with GMF-related vignettes, (e.g., unintentionally eating genetically modified salmon), subjects were asked simply to report what they felt while thinking about GMF. This affords us a more ecologically valid measure of the types of stimuli/vignettes that might naturally come to mind when thinking about whether GMF should be opposed or prohibited.

We also modified the way we probed subjects’ affective states. SIR asked their subjects to report which of the two response options (disgust vs. anger) best reflects their reaction to different GM scenarios. IS used a similar method with three response options (disgust, anger, and fear) instead. However, this method comes with some strong assumptions. First, it forces people to report one feeling or another (leaving no room for the possibility that no emotion is being felt). Second, it operationalizes disgust as the word “disgust” (assuming, once again, a close correspondence between the theoretical and lay meanings of the term, an assumption disconfirmed some 15 years ago; see also our arguments above). Third, it limits the range of non-disgust options to one (“anger” in SIR) or two (“fear” and “anger” in IS), assuming that these states would adequately and fairly cover anything and everything else one could feel in this case. These assumptions are difficult to defend, and therefore call into question the validity of subjects responsesFootnote 7. To address this, in addition to running a conceptual replication of SIR’s study, we designed two additional conditions that do not make these assumptions and so furnish a truer test of what feelings, if any, people experience.

At the beginning of the study, all subjects (N = 1048 recruited, N = 922 retained following attention check) were queried about whether they opposed or did not oppose “genetically engineering plants and animals for food production” (thus separating opponents from non-opponents) and whether they thought it “should be prohibited no matter how great the benefits and minor the risks of allowing it” (with an affirmative answer leading to the subject being classified as an opposing absolutist). Then, after completing a brief attention check, subjects were randomly assigned to one of three affective report conditions: (1) a replication of IS’s study in which subjects were forced to choose between two feeling states, Angry or Disgusted (2-item FC), (2) a 12-item forced choice condition (12-item FC) in which subjects were forced to choose between feeling Afraid, Angry, Bothered, Confused, Creeped out, Excited, Frustrated, Grossed out [a slang term shown to correspond more precisely than “disgusted” to the theoretical meaning of disgust, Nabi, 2002], Neutral, Sad, Suspicious, or Worried, or (3) an open-ended response mode condition (OERM).

The OERM condition was unique in that it left open the possibility that people do not feel or perceive themselves as having affective reactions at all. Rather, in this condition, subjects were prompted to “use the space below to describe (as you would in a diary) what is going though your mind and what you are experiencing as you are thinking about the practice of genetically engineering plants and animals for food production”. Subjects were further enjoined to note that there are “no right or wrong answers” and not to “hold back or self-censor in any way”.

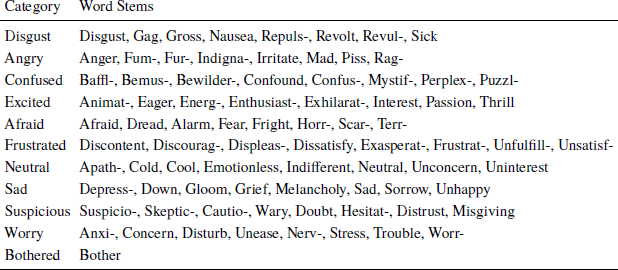

To diagnose the prevalence of affective language in OERM, we carried out a series of content analyses using a total of 81 affective word stems corresponding to the feeling concepts tapped in the 12-item FC condition of the study. 80 of these were organized into 8-item clusters detailed in Table 2 (Appendix). Due to its precise classification being the present point of contention, “creeped out” was retained as a “free-standing” term, though, in our view, the evidence from prior research (Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman et al., 2017; Reference McAndrew and KoehnkeMcAndrew & Koehnke, 2016), clearly substantiates its inclusion in a Fear (Afraid + Worry + Suspicion) super-cluster.

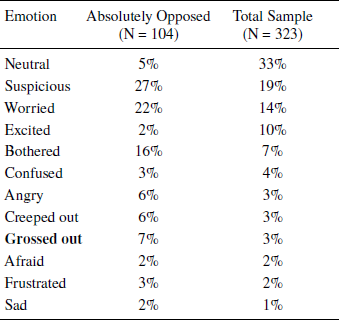

As we predicted, SIR’s procedure for measuring state disgust overestimates the absolute prevalence of disgust in relation to other, more assumption-free methods (see Table 1 above). When subjects’ choices were limited to disgust and anger, disgust substantially and significantly dominated non-disgust for absolute opponents (73.3 percent) as well as for the sample as a whole (62.2 percent). However, only 2.8% of the sample chose “grossed out” in the 12-item FC condition (Table 3, Appendix) and only 1.7% of the sample mentioned one of the target disgust-related words in the OERM condition (Table 4, Appendix), both significant drops from the 62.2 percent, χ2(1, 633) = 256.55, p< .0001 and χ2(1, 598) = 246.5, p< .0001, respectively (based on the “N-1” Chi-squared test as recommended by Reference CampbellCampbell, 2007, and Reference RichardsonRichardson, 2011), with no significant difference between the 12-item condition and OERM (χ2[1, 633] = 0.82, p = 0.36).

Table 1: Proportion of subjects choosing/using disgust-related terms as a function of study condition and evaluative orientation (absolute opposition, non-absolute opposition, non-opposition).

Note. FC = forced choice; OERM = open-ended response mode. Superscripts indicate whether disgust is more dominant than

a is dominated by

b or is equivalent to

c non-disgust by Chi-square goodness-of-fit at α = 0.05.

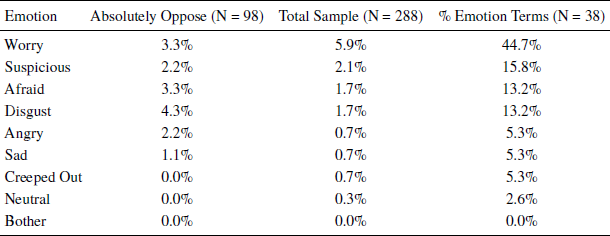

The open-ended response format (Table 4, Appendix), which provides the most assumption-free approach to the problem, suggests that very few people spontaneously perceived themselves as experiencing any emotion at all (41 out of 288, 14.2%). For those apt to experience any feeling at all, feeling worried appears to be three times more common than feeling disgusted (see Appendix for details). Finally, it is worth noting that 1.7 percent (the absolute prevalence of disgust in the open-ended condition) is likely to be an overestimate and that a truly conservative estimate of spontaneously experienced and causally relevant state disgust is likely to be closer to zero (see Appendix for discussion).

These results strongly disqualify disgust as the driver of absolutist opposition in the face of consequentialist reasons. If Reference Scott, Inbar and RozinScott et al.’s (2016) sentimentalist viewpoint was correct, and absolute opposition to GM food was in fact “disgust-based” (p. 316) or “disgust-backed” (p. 322), the last thing one would expect to find is that the majority of GMF’s absolutist opponents feel no disgust at all.

10 Conclusion

In this reply, we defended our critique of the relationship between trait disgust and GMF and extended it to the issue of state disgust. In both cases, SIR and IS appear to overestimate the role that disgust may play in opposing GMF due to imprecisely measuring disgust or by providing limited response options that artificially constrain a subject’s capacity to state their feelings (or lack thereof). When these limitations are addressed, we find a different suite of feelings to come forth, by and large, related to the perceptions of danger, misfortune, or risk.

When considered in the broader context of disgust and moral judgment research, our findings are not at all surprising. A meta-analysis (Reference Landy and GoodwinLandy & Goodwin, 2015), and large-scale replication (Reference Johnson, Cheung and DonnellanJohnson, Cheung & Donnellan, 2014) both conclude that feelings of incidental disgust have practically no influence on moral judgment. Similar in spirit are several past studies (e.g., Reference Fessler, Arguello, Mekdara and MaciasFessler, Arguello, Mekdara & Macias, 2003; Reference Royzman, Leeman and BaronRoyzman, Leeman & Baron, 2009; see also Reference Royzman, Kim and LeemanRoyzman, Kim & Leeman, 2015) that found no significant association between disgust sensitivity and moral evaluations when special design precautions (time delay, misdirection, appropriate controls) were in place. Our own (Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman et al., 2017) study found no relationship between the fine-tuned measure of disgust as OI and either GMF or moral purity concerns (as measured by MFQ-P, Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Spassena and DittoGraham et al., 2011]; r = .14, p = .09).Footnote 8 The findings assembled in recent years have lead another research group to conclude that “there is little evidence for a unique predictive effect of physical, pathogen-based disgust experiences on moral judgments” (Reference Piazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young, Wasserman, Strohminger and KumarPiazza, Landy, Chakroff, Young & Wasserman, 2018, p. 75). From the Bayesian point of view, one’s a priori expectation that disgust predicts GMF moralization should be fairly low.

By contrast, our expectation that people will be principally worried or suspicious about the consequences of GM food should be high. Many studies have provided evidence that people critique GM food based on their unease about the possible harm that genetically modified food may have on the populace, and express a suspicion that scientists have not studied GM sufficiently or long enough to rule out negative effects (e.g., Reference Chen and LiChen & Li, 2007; Reference Connor and SiegristConnor & Siegrist, 2010; Reference Onyango and NaygaOnyango & Nayga, 2004; Reference Prati, Pietrantoni and ZaniPrati, Pietrantoni & Zani, 2012; Reference Rzymski and KrólczykRzymski & Krolczyk, 2016). Indeed, a review of subjects’ verbatim statements in the OERM condition of our study, indicates that 60 percent of the absolutist opponents and 65 percent of all opponents were thinking uniquely in terms of harm and risk.

All in all, our study (Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman, et al., 2017) was methodologically and conceptually sound. Our critique, as well as our novel findings, fit neatly with the recent pattern of findings showing that disgust plays little role in moral judgment. The burden of proof is on those who wish to claim otherwise.

Appendix: Study re-assessing the prevalence of state-disgust

Method

Subjects.

We recruited 1048 individuals from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (561 reported Female, AgeM = 35.7 AgeSD = 12.23).

Procedure and Design.

At the beginning of the study, all subjects were queried about whether they opposed or did not oppose “genetically engineering plants and animals for food production” (thus separating opponents from non-opponents) and whether they thought it “should be prohibited no matter how great the benefits and minor the risks of allowing it” (with the affirmative answer leading to the subject being classified as an opposing absolutist). This allowed us to sort each subject in one of the three categories: absolutist opponent, non-absolutist opponent, non-opponent. Then, after completing a brief attention check, subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three affect report conditions described below: (1) a two-item forced choice condition (2-item FC) serving as a replication of the study reported in SIR, (2) a 12-item forced choice condition (12-item FC), or (3) an open-ended response condition (OERM).

In the 2-item FC (modeled after Scott et al., 2016) and 12-item FC conditions, subjects were asked to indicate which of the available affect terms best described what they felt while thinking about genetically engineering plants and animals for food production. In 2-item FC, the options were limited to Angry and Disgusted. In the 12-item condition, the options were considerably broader: Afraid, Angry, Bothered, Confused, Creeped out, Excited, Frustrated, Grossed outFootnote 9, Neutral, Sad, Suspicious, and Worried.

We reasoned that “worry”, “suspicion”, and other aforementioned terms would constitute better alternatives to disgust than “anger” (or “fear”). The bulk of the published data on GMF attitudes shows that people are concerned about the possible harmful consequences that these products may have on their well-being or health, and are suspicious that scientists have studied GM sufficiently or long enough to rule out key negative effects (e.g., Reference Chen and LiChen & Li, 2007; Reference Connor and SiegristConnor & Siegrist, 2010; Reference Onyango and NaygaOnyango & Nayga, 2004; Reference Prati, Pietrantoni and ZaniPrati, Pietrantoni & Zani, 2012; Reference Rzymski and KrólczykRzymski & Krolczyk, 2016). And, as pointed out by Jonathan Baron (personal communication, June 15, 2018), “worry” is also the affective category most commonly cited in Slovic’s “psychometric approach to risk” studies of lay responses to emerging technologies and medicine (e.g., Reference Peters, Slovic, Hibbard and TuslerPeters, Slovic, Hibbard & Tussler, 2006; Reference SlovicSlovic, 2000). Consistent with Slovic, we see worry largely as the ruminative cousin of fear, arising as part of the affective sequelae of prospecting (Reference Seligman, Railton, Baumeister and SripadaSeligman, Railton, Baumeister & Sripada, 2013) future threats over which one can exert some (but only partial) control.

The two forced choice conditions were alike in that all the subjects had to feel something, and it was up to us, the researchers, what feelings they could express. By contrast, in the third open-ended response mode (OERM) condition, we left open the possibility that people do not feel anything at all. Rather, in this condition, subjects were prompted to “… use the space below to describe (as you would in a diary) what is going though your mind and what you are experiencing as you are thinking about the practice of genetically engineering plants and animals for food production.”

The subjects were further enjoined to note that there are “no right or wrong answers” and not to “hold back or self-censor in any way”Footnote 10. This circumlocution was motivated by several prior reports (reviewed by Feldman Barrett, 2017) suggesting that framing an affect-related question in terms of specific emotion concepts or feelings may result in an overestimate of a particular affective state due to subjects’ constructing their internal experiences around the concepts in question. Thus, the OERM condition was the most conservative (assumption-free) of the three experimental conditions in that it made no direct reference to affect.

Emotion coding.

To diagnose the prevalence of affective language in OERM, we carried out a series of content analyses using a total of 81 word stems corresponding to the feeling concepts tapped in the 12-item FC condition of the study. 80 of these were organized into 8 item-clusters detailed in Table 2.Footnote 11 (No affective cluster was formed around “bothered” due the extremely low granularity of the term.) Due to its precise classification being the present point of contention, “creeped out” was retained as a “free-standing” term, though, in our view, the evidence from prior research (Reference Costello and OsborneRoyzman et al., 2017; Reference McAndrew and KoehnkeMcAndrew & Koehnke, 2016), clearly substantiates its inclusion in the Fear (Afraid + Worry + Suspicion) super-cluster.

Table 2: 81-word affective word stems used in the OERM condition of the study.

Note. In all cases, subjects either used a single affective term or two affective terms from the same cluster, making all responses assignable to a single cluster.

Results and discussion

124 subjects (12% of our entire sample) failed a brief attention check and were removed. Including these individuals has no noticeable effect on the results. All analyses reported below were performed on the remaining 922 subjects. Of these subjects, 424 (46%) indicated that they opposed GMF. Of people who indicated that they currently oppose GMF, 312 (74%) agreed with the statement that GMFs should be prohibited “no matter what”, and thus would be considered as “absolutist” opposers by SIR’s criterion.

As we predicted, SIR’s procedure for measuring state disgust overestimates the absolute prevalence of disgust. When subjects’ choices were limited to disgust and anger, disgust substantially and significantly dominated non-disgust for absolute opponents (73.3 percent) as well as for the sample as a whole (62.2 percent; see Table 1, main text). By contrast, only 2.8% of the sample chose “grossed out” in the 12-item FC condition (Table 3), and only 1.7% of the sample mentioned one of the target disgust-related words in the OERM condition (Table 4), both significant drops from 62.2 percent, χ2(1, 633) = 256.55, p< .0001 and χ2(1, 598) = 246.5, p< .0001, respectively (based on the “N-1” Chi-squared test as recommended by Campbell, 2007, and Richardson, 2011]), with no significant difference between the 12-item condition and OERM (χ2[1, 633] = 0.82, p = 0.36).

Table 3: Frequency of feeling states selected in the 12-emotion forced choice condition.

Note. Rows ordered by rank frequency in total sample. “Grossed out” highlighted to indicate rank.

Table 4: Frequency of feeling states selected in the open response choice format condition.

Note. Rows ordered by rank frequency in total sample. Disgust highlighted to indicate rank.

Disgust does not appear to be an especially prominent feeling for people absolutely opposed to GMF, either. Only 6.7% of these subjects selected “grossed out” and only 4.3% of these subjects provided one of the disgust-cluster words in OERM (with 4 out of 5 cases using the non-specific word “disgust”, which commonly means merely “disapproval”). These both represent substantial decreases from SIR’s 2-condition method,χ2(1, 220) = 99.51, p< .0001 and χ2(1, 208) = 99.31, p< .0001, respectively (with no significant difference between 12-item FC and OERM, χ2[1, 196] = 0.53, p = 0.46). In contrast to disgust, other feelings, e.g., worry, suspicion, and apathy were far more common in people’s reactions. The open-ended response format, which provides the most assumption-free approach to the problem, suggests that very few people spontaneously perceived themselves as experiencing any emotion at all (41 out of 288, 14.2%), though opponents appeared somewhat more likely to do so (24/140, 17%) than non-opponents (14/148, 9.5%), χ2(1, 288) = 3.07, p = .08.

For those apt to experience any feeling at all, feeling worried appears to be three times more common than feeling disgusted (Table 4), though even worry comprises a relatively small proportion of the overall sample (5.9% for worry vs 1.7% for disgust). The sheer paucity of affect under OERM is in striking contrast to the conclusions one might have drawn from the 2-item FC. Finally, it is worth noting that 1.7 percent (the absolute prevalence of disgust in the open-ended condition) is likely to be an overestimate. As indicated earlier, in everyday speech, “disgust” or “disgusting” are often used to signify “immoral”, “bothered”, or “disliked”. This also likely overestimates the extent to which these feelings would be causally implicated in (or be even temporally antecedent to) the rise of absolutist disapproval. Thus, a truly conservative estimate of spontaneously experienced and causally relevant state disgust (disgust quo OI) is likely to be closer to zero.

Disgust words vs. disgust faces

There is little doubt that IS/SIR would challenge these results. They could, for example, argue that their 2016 assessment was not predicated solely on emotion words. In their original study (Reference Ekman, Matsumoto, Friesen, Ekman and RosenbergScott et al., 2016), some subjects indicated their preference by being asked to select from a set of facial displays: two anger faces (the “maximal” anger face in the open mouth form with bilateral lip raise and the “minimal” anger face in the lip press form) and two disgust faces (the “maximal” gape/tongue protrusion disgust face and the “minimal” bilateral upper lip raise disgust face).

There are a number of problems with this method – key among them is the inclusion of the minimal disgust face as one of the bases for demarcating disgust from anger. As Reference Rozin, Lowery and EbertRozin et al. (1994) themselves have observed,

“Among disgust situations, upper lip raise [AU 10] was the significant (p < .01) predominant response in two cases: ‘seeing a deformed person’ and ‘looking at pictures of the slaughter at a WWII concentration camp’…Upper lip raise was also the predominant response for anger, contempt, and rights violation (stealing), confirming its role in the anger expression. Thus…the major results of the choice test… affirm a link between upper lip raise and other moral emotions.” (p. 878).

According to Rozin et al.’s own data (see also Reference Widen, Pochedly, Pieloch and RussellWiden et al., 2013), the upper lip raise AU was not selectively related to the experience of disgust. Thus, it appears that, as with “disgust” itself, one of the constituent disgust displays lacks discriminant validity as a gauge of disgust vs. anger, contempt, and disapproval as well as any capacity to differentiate between physical and socio-moral domains.

To address this concern, we re-analyzed Scott et al.’s study comparing the maximal (gape) disgust face with its maximal anger counterpart.Footnote 12 With the minimal disgust and anger faces removed, we no longer observed significant anger/disgust differences for any of the four scenarios. This was the case irrespective of whether we looked at the sample as a whole or limited our analyses to GMF opponents only.

One could also argue that forcing subjects to choose between two types of facial configurations that visually stereotype two folk emotion concepts inherits all or most of the problems we discussed above in the context of emotion words. These include the key criticism that applied to the forced-choice approach: people are forced to “feel” something (leaving no room for the hypothesis that they process the information in an emotion-free way). And the most likely emotions, including suspicion, worry, or apathy, are clearly not on the list. The face of fear is fundamentally a face of terror and there is simply no established facial configuration for the lower-activation states of “worry”, “suspicion”, or “concern”.

Finally, because Inbar and Scott’s presentation of their newer findings emphasize faces over words, it is worth noting that many of the theoretical and methodological assumptions underlying this method have been strongly and repeatedly questioned (see Reference RussellRussell, 1994, 2003; Feldman Barrett, 2017 for discussion). In our view, the use of facial displays is still of historical interest, but its current scientific status is so unsettled that its use as a means to resolve yet another scientific debate is contentious at best.