1 Introduction

In 1958, H. L. A. Hart and Lon Fuller held a heated exchange about the nature of rules in the Harvard Law Review. Hart maintained that a rule’s text was enough to solve most legal cases, while Fuller insisted that it was never sufficient to determine its scope. According to Fuller, the purposes behind rules — their morally laudable ends — were always at play when judging whether they had been obeyed or violated. Their debate was brought to life through competing lines of reasoning about a rule forbidding vehicles in a public park.

Hart first proposed the example in an attempt to show that, no matter how indeterminate legal language might be in certain cases, rules retain a core of undisputed meaning and this meaning is capable of settling legal disputes: We may debate whether “bicycles, roller skates, [and] toy automobiles” are vehicles according to the park’s rule, but regular cars are clearly prohibited. We do not need to exercise any moral reasoning in order to apply the no-vehicles rule to cars.

Fuller took issue with Hart’s understanding of the no-vehicles rule. In Fuller’s view, even the most paradigmatic violations of a rule demand a consideration of the purpose behind the rule’s existence. Fishing for both his readers’ and Hart’s intuitions, Fuller asked:

What would Professor Hart say if some local patriots wanted to mount on a pedestal in the park a truck used in World War II, while other citizens, regarding the proposed memorial as an eyesore, support their stand by the “no vehicle” rule? Does this truck, in perfect working order, fall within the core or the penumbra (Reference FullerFuller, 1958, p. 663)?

For Fuller himself, this was an easy case: The intuitively obvious response is that the memorial truck is allowed in the park. To see that regular cars are prohibited and the memorial truck is allowed, we need to think beyond the rule’s text, resorting to its purpose. According to Fuller, a rule’s purpose is the moral goal it pursues. For example, it would be reasonable to infer that the purpose of a prohibition on vehicles in the park is to keep park-goers safe.Footnote 1 Since a regular car driving through the park would pose a risk to visitors’ safety, it falls within the scope of the rule. The memorial truck poses no comparable risk, and hence falls beyond it.

Although the debate may seem inconsequential, the “no vehicles in the park” rule has become a centerpiece of legal theoryFootnote 2 — so pervasive in fact that, on April 1st, 2012, Lawrence Solum posted the following on his Legal Theory Blog:

Frederick Schauer (University of Virginia School of Law) has posted No More Vehicles in the Park on SSRN. Here is the abstract:

In prior work, I have examined the memorable controversy about the fictional legal rule prohibiting vehicles in the park, which first appeared in the 1958 debate between Lon Fuller and H.L.A. Hart. That essay focused on the original version of the thought experiment as presented by Hart. In this essay, I examine a series of classic variations found in the work of other theorists, including “ambulance in the park,” “tricycle in the park,” “motorized wheelchair in the park,” “radio-controlled toy car in the park,” “tank memorial in the park,” and “silent hovercraft in the park.” Drawing on Daniel Dennett’s critique of thought experiments as intuition pumps, this essay shows that many (if not all) of these variations are simply incapable of generating valuable insights about legal rules, legal interpretation, and the nature of legal language. I conclude by suggesting that the proliferation of vehicle-in-the-park thought experiments be terminated.Footnote 3

This, of course, was an April Fools’ joke inspired by Reference SchauerSchauer’s (2008) own take on the hackneyed thought experiment.Footnote 4 But the joke is telling. For decades, legal philosophers have obsessed over the numerous variants of this thought experiment that helped to immortalize the dispute between Hart and Fuller. Why did this particular thought experiment become so fundamental to legal philosophy?

One of the reasons is its implications for a deeper jurisprudential disagreement about the nature of law. Legal positivists, including Hart, hold that law and morality are conceptually distinct and that one can ascertain what the law is without resorting to moral criteria (Reference GardnerGardner, 2001). In Schauer’s words, “if law is to be understood as not necessarily incorporating moral criteria for legal validity, then there must exist some possible rules in some possible legal systems that can be identified as legal without resort to moral criteria” (Reference SchauerSchauer, 2008, p. 1113).Footnote 5 Since the textual interpretation of a rule, according to its ordinary meaning, does not in principle demand moral scrutiny, this so-called textualist view of rules is compatible with positivism.Footnote 6

Advocates of natural law such as Fuller, on the other hand, take law and morality to be conceptually intertwined, so that the identification of law is necessarily a matter of moral evaluation. According to Schauer, “in offering [his] example, Fuller meant to insist that it was never possible to determine whether a rule applied without understanding the purpose that the rule was supposed to serve” (2008, p. 1111). If we always — in all conceptually possible legal systems — need to engage in purpose-driven moral reasoning in order to determine what the law requires, then there is a necessary conceptual connection between law and morality. So, Fuller’s purposivism is a natural law position. In this way, the Hart-Fuller debate, though focused on legal interpretation specifically, bears upon a more fundamental debate concerning the nature of law.

Aside from these divergent conceptual implications, the Hart-Fuller debate also turns centrally on a particular empirical disagreement:

Fuller is arguing not only that his purpose-focused approach is a necessary feature of law properly so called, but also that it is an accurate description of what most judges and other legal agents would actually do in most common law jurisdictions. On this point Hart might well be read as being agnostic, but there is still a tone in Hart of believing that Fuller not only overestimates the role of purpose in understanding the concept of law, but may well also be overestimating the role of purpose and underestimating the role of plain language in explaining the behavior of lawyers and judges (Reference SchauerSchauer, 2008, p. 1130).

The way lawyers and judges actually think and use the concept of a rule is, according to this characterization of the debate, decisive. If legal professionals generally decide that legal rules cover certain cases without resorting to purposive or moral considerations, positivism may better capture legal cognition. If, instead, the ordinary concept of a rule generally begets a moral appraisal, natural law theory may offer a more accurate account.

But what are the reasons one could have to prefer textualism or purposivism? To understand this normative question, it pays to examine one interesting feature of rules. Legal rules typically regulate action-types (e.g., driving under the influence), but these action-types acquire value insofar as they probabilistically influence one or more of the authority’s objectives (e.g., protecting people’s lives). As a result, action proscriptions in the law are in general both imperfectly sensitive (since some drivers may ingest alcohol yet pose no special risk to road safety) and imperfectly specific (since other drivers pose a risk to road safety even without ingesting alcohol). These imperfections lead us to ask why we should proscribe types of actions, if these proscriptions are mere heuristics and the ultimate goal of law is to promote desirable outcomes. One possible answer is that it is easier, and less subject to controversy, to limit oneself to a rule’s text than to consider every consequence and assess its probability. Another answer is that simple rules sometimes lead to better consequences (on average) when the attempt to decide on the basis of consequences is subject to bias or large errors (Reference Gigerenzer, Todd, Gigerenzer and ToddGigerenzer & Todd, 1999; Reference Gigerenzer, Engel, Gigerenzer and EngelGigerenzer & Engel, 2006). The same kind of reasoning applies to rules outside of the legal domain, such as moral norms.

Those two advantages are highlighted by the literature on normative models of decision-making in law. Reference SchauerSchauer (1991, 1988) points out that formalism — the commitment to apply the rule’s text even when this seems to be wrong vis-à-vis an all things considered reasoning — yields faster and cheaper decisions than the alternative of trying to find the optimal moral solution to every legal case (a position he calls particularism). He also points out that formalist judges will often be better on aggregate than their particularistic counterparts, because particularists will err more often, given the complexity of moral decision-making and the relative simplicity of following rules’ authoritative linguistic formulations.

Furthermore, when interpreted textually, rules that establish linguistically determinate action-types tend to better promote predictability and coordination among their subjects. Legislators in heterogeneous societies where values are disputed frequently do not agree with regards to outcomes but they will eventually vote on an agreed text. A norm presented in clear wording which requires certain actions and excludes others will at least allow subjects with different moral outlooks to know what is expected of them, thus allowing them to plan their lives accordingly. Even among groups composed exclusively of well intentioned people who hope to do what is good or right, clear-cut proscriptions of actions are necessary for coordination and predictability, if these people diverge regarding the right and the good. Given the indelible predicament of profound moral disagreement in plural societies, some legal philosophers have advocated, contra Fuller, that law be taken as a set of determinate rules to be understood according to their text:

Thus, if people were gods — morally omniscient, but not angels, morality would be an adequate guide to behavior and posited norms would be unnecessary. If, however, people were angels but not gods, then posited norms in the form of determinate rules would be necessary to implement morality. Law as determinate rules is a solution to a cognitive, not a motivational, problem (Reference Alexander and SherwinAlexander & Sherwin, 2001, 219).

The mock abstract Solum attributed to Schauer culminated with a suggestion that “the proliferation of vehicle-in-the-park thought experiments be terminated”. We would not go that far, but we definitely sympathize with the urgent need for a change of focus. Hart and Fuller can be viewed as advancing competing empirical predictions about the way legal agents understand, interpret, and apply rules. As such, we may be able to arbitrate between their contrasting views through empirical research. In order to shed light on legal agents’ concept of a rule, thought experiments won’t do. We need to conduct actual experiments.

Furthermore, there are important reasons to examine naive subjects’ intuitions as well. After all, the law is directed at all of us, and citizens’ intuitions about rules are important in order to understand how they conceive the rules’ demands. As one prominent legal philosopher of law recently put it:

In one way or another the law plays a role in the practical reasoning of everyone in society, and in reasonably well functioning societies, law works as an internal guide to (nearly) everyone in society, and not just to appellate judges. It is to say that a general jurisprudential theory would be radically incomplete and seriously misleading, if it failed to give some account of the place of law in the practical reasoning of officials, lawyers, and lay citizens alike (Reference PostemaPostema, 1991, pp. 799–800).

Following in the footsteps of recent work on experimental jurisprudence (Reference Donelson, Hannikainen, Lombrozo, Knobe and NicholsDonelson & Hannikainen, 2020; Reference Kneer and MacheryKneer & Machery, 2019; Reference MacleodMacleod, 2019; Sommers, forthcoming; Reference TobiaTobia, 2018, forthcoming), we employ the methods of experimental philosophy to reveal how people ordinarily understand and apply the concept of a rule. This fills an important gap, since current experimental investigations into the tension between text and purpose (Reference Turri and BlouwTurri & Blouw, 2015; Reference TurriTurri, 2019; Reference Garcia, Chen and GordonGarcia, Chen & Gordon, 2014) miss some of the most important conceptual features of rules in law and in life (Reference SchauerSchauer, 1991). We take the ordinary concept to be the concept that non-philosophers, understood as both the folk and legal professionals, employ in their use of language.

We tested both legal and non-legal rules because the concern of the Hart-Fuller debate — the tension between text and purpose in the making of a rule — obviously extrapolates the field of legal theory. We also used non-legal rules because it seems to be a common practice among legal philosophers to assume that discussing non-legal prescriptive rules can help illuminate legal rules themselves. In this sense, sport rules (Reference HartHart, 1994), household rules (Reference Twinning and MiersTwining & Miers, 2010), parenting rules (Reference SchauerSchauer, 1991) and many others can be found in discussions within jurisprudence. As one book clearly expresses:

All of us are confronted with rules every day of our lives. Most of us make, interpret and apply them, as well as rely on, submit to, avoid, evade and grouse about them; parents, umpires, teachers, members of committees, business- people, accountants, trade unionists, administrators, logicians and moralists are among those who through experience may develop some proficiency in handling rules. Lawyers and law students are specialists in rule-handling, but they do not have a monopoly of the art. A central theme of this book is that most of the basic skills of rule-handling are of very wide application and are not confined to law. There are certain specific techniques which have traditionally been viewed as ‘legal’, such as using a law library and handling cases and statutes. But these share the same foundations as rule-handling in general: they are only special in the sense that there are some additional considerations which apply to them and are either not found at all or are given less emphasis in other contexts (Reference Twinning and MiersTwining & Miers, 2010, xiv).

We investigated people’s intuitions about a series of putative rule infractions through correlational (Study 1) and experimental (Studies 2, 3 and 4) methods. Our findings reveal that people spontaneously consider both a rule’s text and its purpose when determining whether a particular incident constitutes an infraction. Yet experimental manipulations of textual compliance yielded stronger effects than did manipulations of purposive violation — a pattern mirrored in participants’ subjective assessments. Finally, the weight of moral considerations upon judgments of rule infraction varied across experimental conditions. In spontaneous conditions, judgments of rule infraction depended more on the blameworthiness of the agent — but analytic conditions annulled this effect.

2 Study 1

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

272 volunteers (mean age = 24.6, 169 women, 227 reported no legal training) were recruited through snowball sampling on social media and completed the survey.

2.1.2 Design

In a correlational design, we asked participants to consider a rule and report whether an agent committed an infraction, and whether they had violated the text and/or the purpose of the rule.

2.1.3 Procedure

Participants first read an adaptation of Reference SchauerSchauer’s (1991) “no dogs in the restaurant” rule. The introduction described a previous incident involving a customer’s dog jumping, running and barking in the restaurant. This incident led the owner to “ban dogs from the restaurant” (the rule’s text) in order to “avoid behaviors that cause nuisances to the restaurant’s customers” (the rule’s purpose). Thus, both the rule’s text and its purpose (the normative goals the creator of the rule aimed to achieve) were explicitly stated in the introduction to the study.

Respondents then viewed a random subset of four scenarios from a battery of eight (seeFootnote 7), describing a putative infraction of the no-dogs rule. The scenarios introduced variation along four related dimensions: being a dog, looking like a dog, behaving like a dog, and annoying other customers. In some scenarios, the client brought a misbehaved dog (“…a dog that runs, jumps, barks and eats food from the floor”), in others, a well-behaved dog (“… a purse containing what seems to be a teddy bear. Actually, it’s her dog, who doesn’t bark and barely moves, being easily mistaken for a toy”). Other scenarios included something that looks like a dog, but doesn’t behave like one (“…a taxidermied dog”), and something that acts like a dog, but doesn’t look like one (“…a dog in an extremely realistic pig costume”).

After each scenario, participants were asked “Did he/she break the rule?”. Responses were recorded as either (1) “Yes” or (0) “No”. Alongside their rule infraction decisions, participants were asked to assess four features of the case at hand — namely, whether the animal/object:

(i) “was a dog” (identity),

(ii) “looked like a dog” (appearance),

(iii) “behaved like a dog” (behavior), and

(iv) “bothered other customers” (purpose).

Each assessment was recorded on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1: “Clearly not” to (7) “Clearly yes”. Of the first three assessments, the first (i.e., identity) reflects the most direct interpretation of the rule’s text. Thus, we predicted that identity judgments would reveal a stronger association with rule infraction decisions than either appearance or behavior judgments. The fourth assessment asked directly about the rule’s stated purpose.

The introduction to the rule stipulated that the rule’s text is “no dogs allowed in the restaurant” (text) in order not to “bother other customers” (purpose). By asking whether there is a dog in the restaurant, and whether it bothered other customers, we sought to capture commensurate estimates of the effect of textual and purposive considerations in infraction decisions.

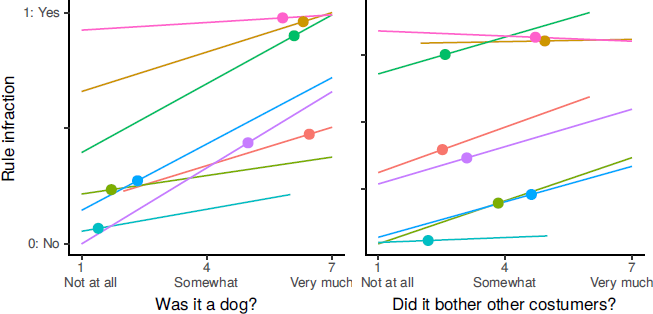

2.2 Results

We entered rule infraction judgments as the dependent measure in a mixed-effects, logistic model with participant and scenario as crossed random effects. We evaluate the fixed effect of each assessment in a series of simple linear regressions, allowing random slopes by participant and scenario. Both identity and purpose judgments revealed robust effects (identity: OR = 1.57, z = 7.03; purpose: OR = 1.30, z = 3.70; ps < .001). In turn, judgments of appearance and behavior revealed weaker associations with infraction decisions (appearance: OR = 0.91, z = −1.21, p = .23; behavior: OR = 1.14, z = 2.1, p = .034).

Querying our causal assumptions helps to further interpret this pattern of results. While ‘being a dog’ is a cause of ‘looking like a dog’ and ‘behaving like a dog’, the opposite is not true. Thus, a ‘backdoor path’ connects behavior to infraction decisions (i.e., Behavior ← Identity → Infraction; see Reference PearlPearl, 2009) — confounding the bivariate analysis above. In a multiple regression analysis, participants’ infraction decisions were predicted by assessments of behavior (OR = 1.34, if anything higher than without the covariate, z = 2.67, p = .007), after accounting for the effect of assessments of identity (OR = 1.67, z = 5.10, p < .001).

A similar line of reasoning may suggest that the effect of purpose too is confounded (i.e., Purpose ← Behavior/Identity → Infraction): Specifically, one could think that ‘being a dog’ and ‘behaving like a dog’ both cause ‘bothering other customers’ and, ex hypothesi, rule infractions. And yet, in a multiple regression analysis, participants’ purpose assessments predicted their infraction decisions (OR = 1.51, z = 3.53, p < .001), even when conditioning on both confounds (identity: OR = 2.00, again higher than when alone, z = 5.27, p < .001; behavior: OR = 1.42, z = 2.39, p = .017).

Finally, the above analyses do not distinguish subject variation from case variation. Looking at the point-biserial correlation between purpose assessments and infraction decisions revealed positive coefficients (rs) ranging from .02 to .21 (.80 < ps < .015) for all but one scenarioFootnote 8 — suggesting that the effect of purpose assessment is not due solely to variation across cases (see Figure 1). Still, first and foremost, the Hart-Fuller debate concerns our intuitions regarding different cases, i.e., the intuitions we feel when considering the car entering the park versus the memorial truck, and not differences between individuals when perceiving the same case. Thus, the primary concern in Study 1 was to examine the features of cases that are seen as involving a rule infraction (Figure 1). For instance, an overwhelming majority of participants judged the misbehaved dogs (97% without and 96% with a pig costume) to be in violation of the rule, while only a slim minority (7%) judged a goldfish to violate the no-dogs rule (see Table 1). Finally, cases where textual and purposive assessments supported opposing verdicts yielded substantial division: For instance, the guide dog was judged to be in violation of the rule by 48% of participants.

Figure 1: Effects of identity and purpose assessments on infraction decisions. Case means are overlaid.

Table 1: Displays summary statistics for each of the putative infractions in Study 1.

2.3 Discussion

‘Being a dog’ (identity) and ‘bothering customers’ (purpose) were the strongest predictors of participants’ decisions about whether the no-dogs rule had been violated. Meanwhile, ‘acting like a dog’ and especially ‘looking like a dog’ yielded notably weaker effects. Thus, in the context of a non-legal rule, lay decisions regarding a series of putative infractions appeared to reflect the very concerns that dominate the jurisprudential debate between Hart and Fuller: the rule’s text and its purpose.

The results of Study 1 also provide tentative support for a textualist approach to interpretation. Participants were more likely to report that the rule was broken by well-behaved dogs than by bothersome non-dogsFootnote 9 — despite having stipulated both the text and the purpose of the rule. This pattern of results echoes a broad theme in moral psychology: People exhibit a strong adherence to simple action proscriptions, adopting this policy even in contexts in which an alternative action plan would yield the superior outcome (Reference Baron and SprancaBaron & Spranca, 1997; Reference BartelsBartels, 2008).

However, the conclusions of Study 1 rest on a single rule. In addition, Study 1 relied on participants’ subjective assessment of whether the rule’s text and purpose had been violated. We address these limitations in Study 2 by surveying a broader set of rules, while experimentally manipulating whether the text and purpose were violated.

3 Study 2

One of the defining features of rule-based decision-making is the possibility that text and purpose will diverge. Imagine that John, in hopes of keeping his apartment clean, establishes a rule according to which no one is allowed to enter his home with shoes on. To make his decision clear, he hangs a sign on the front door saying “no shoes allowed in the house”.

Suppose that a friend walks barefoot in the mud outside John’s apartment. She would not, according to the rule’s text, be barred from entering John’s apartment — though doing so would most certainly dirty the floor. Reference SchauerSchauer (1991) calls cases like this, where a rule’s text fails to cover actions that violate the rule’s purpose, cases of underinclusion.

Now, imagine that a second friend bought a brand new pair of shoes. According to the rule’s text, this friend would not be allowed to try her new shoes on inside John’s apartment — even though doing so would not dirty the apartment in any way. Schauer calls cases like this, where a rule’s text proscribes behavior that does not violate the rule’s purpose, overinclusion cases.

Thus, in two different ways, appraisals of the text of a rule give rise to verdicts that fall short of the rule’s guiding spirit. In addition to Schauer’s categories, we can also define core cases as those in which the rule is violated on both grounds of text and purpose (for instance, dirty boots), and off-topic cases where neither text nor purpose prohibit the action (someone enters John’s apartment barefoot and with clean feet).

In Study 2, we devised scenarios of all four types: core, overinclusion, underinclusion, and off-topic cases. What would Hart and Fuller predict about each? They would agree that core cases are rule violations while off-topic cases are not. Their theories, however, make competing predictions about overinclusion and underinclusion cases.

Hart’s textualism would predict that people are more willing to take overinclusion cases to be rule violations than underinclusion cases. What’s more, by agreeing that cases of overinclusion constitute rule violations nonetheless, people would be expressing that, at least sometimes, rules cover circumstances in which they yield morally undesirable outcomes. By the same token, if people denied that underinclusion cases violate the rule at hand, they would be implying that purposive considerations do not suffice to determine whether a rule has been violated. This pattern of results would be congenial to a positivist like Hart.Footnote 10

Fuller would disagree. He held that law makes sense only as a purposive enterprise. According to this view, people are much more concerned with advancing the goals that inspired a rule than with abiding by their specific textual formulation. As such, the Fullerian prediction would be the exact opposite of the Hartian prediction: namely, that underinclusion cases should be viewed as rule violations more often than are overinclusion cases.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

200 volunteers (mean age = 28.6, 116 women, 101 reported no legal training) were recruited through sponsored posts and snowball sampling using social media and completed the survey.

3.1.2 Design

In a 2 (text: abide vs. violate) × 2 (purpose: abide vs. violate) Latin square design, participants read about four scenarios: No Shoes in the House, No Vehicles in the Park, No Sleeping at the StationFootnote 11, and No Cellphones in Class (see Supplementary Materials).

3.1.3 Procedure

After each scenario, participants were asked whether the agent violated the rule, and responses were recorded as either (1) “Yes” or (0) “No”. Alongside their rule infraction decisions, participants were asked to make two assessments about the case at hand — namely, whether:

(i) the rule’s text was violated (e.g., “Did Jane wear shoes in the house?”), and

(ii) the rule’s underlying purpose was violated (e.g., “Did Jane dirty the house?”).

Both assessments were made on seven-point scales, ranging from 1: “Clearly not” to (7) “Clearly yes”.

3.2 Results

Manipulation checks revealed that violations of the rule’s text were rated higher on the textual assessments, B = 3.64, t = 24.11, p < .001. Correspondingly, violations of the rule’s purpose were rated higher on the purposive assessment, B = 1.55, t = 10.48, p < .001.

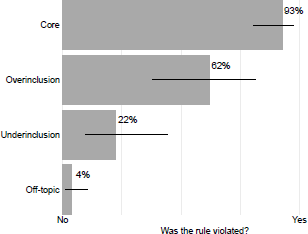

Looking at a wider variety of legal and non-legal rules, we replicated the effect in Study 1. Experimental manipulations of both text (B = 3.76, z = 11.69, p < .001) and purpose (B = 2.04, z = 7.56, p < .001) violations increased the probability of perceived infraction. Critically, in a pairwise comparison (OR = 5.60, z = 6.73, p <.001), cases of overinclusion (![]() = .62) were more likely to be considered rule violations than were cases of underinclusion (

= .62) were more likely to be considered rule violations than were cases of underinclusion (![]() = .22), as depicted in Figure 2.Footnote 12 The same pattern of results holds when we restrict the analysis to those with legal training.Footnote 13

= .22), as depicted in Figure 2.Footnote 12 The same pattern of results holds when we restrict the analysis to those with legal training.Footnote 13

Figure 2: Predicted probability of a rule violation by scenario type.

3.3 Discussion

Both textual and purposive violations were treated as rule infractions. However, extending the results of Study 1, overinclusion cases (violations of the text that do not infringe upon the rule’s purpose) were more likely to be seen as infractions than were underinclusion cases (violations of the purpose that are not captured by the rule’s text).Footnote 14 Thus, once again, a rule’s text appeared to play a predominant role in infraction decisions.

Rules may be thought of as proscribing actions that hinder the rule’s purpose in most conditions. The results of Study 2 add nuance to this picture: Infraction decisions were determined primarily by the action (i.e., bringing a vehicle to the park, wearing shoes in the house), even when the resulting outcome was known (e.g., whether the park-goers were endangered, or the apartment was dirtied). This result suggests that abiding by the rule’s text is encoded as a source of intrinsic, and not merely instrumental, value (Reference BlairBlair, 1995; Reference BartelsCushman, 2013).

4 Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 focused on cases that we might describe as clear-cut: Each potential infraction unambiguously violated the rule’s text and/or its purpose (or else, the action clearly violated neither). However, the cases that stoke jurisprudential interest often involve some degree of uncertainty: i.e., either it is unclear whether the putative infractor’s action is described by the rule’s text, or it may be unclear whether the action violates the rule’s purpose.

For Study 3, we developed a new battery of 24 borderline cases. For instance:

One day, in a high profile case, a 21 year old young woman got into a deadly traffic accident. The accident happened because the young woman was using her smartphone in one hand to text her friends while driving. Congress, recognizing the graveness of the situation and with the goal of avoiding this type of accident, passed a law with the following textual formulation: “it is forbidden to send text messages while driving”.

This time, however, the particular action did not clearly violate the text of the rule:

Felipe uses the voice-to-text functionality of his smartphone to text his friends. While doing so, Felipe suffers a serious accident with another vehicle, severely injuring the occupants of both cars.

There is some ambiguity in whether Felipe complied with the rule’s text. On the one hand, he was sending text messages by using his phone (which processed his voice into text). On the other hand, neither his hands nor his eyesight were diverted from driving.

Analogously, other cases were unclear as to whether or not the protagonist’s behavior violated the rule’s stated purpose: e.g., a case where someone who was harassed for being agnostic in a Catholic country uses an ecumenical chapel created to protect religious minorities to read the biography of an atheist mathematician.

Study 3 introduced a further change to the way participants’ decisions were elicited. In our first two studies, we asked participants to simultaneously consider the rule’s text and its purpose — while they decided whether the rule had been violated. This feature of our protocol could have primed participants to consider these factors in their infraction decisions to a greater extent than they spontaneously would have. To reveal the balance of textual and purposive considerations in spontaneous circumstances, in Study 3 participants made rule infraction judgments in isolation. Participants in other conditions judged whether the text was violated, or whether the violator was morally blameworthy.

Finally, instead of asking whether the purpose had been violated (“Did Felipe’s behavior cause an accident?”), we asked whether putative infractors were morally blameworthy for the outcomes they brought about (“Is Felipe morally blameworthy for using the voice-to-text functionality of his smartphone to communicate with his friends while he was driving?”). Insofar as the purposes in our scenarios were univocally good, ascriptions of blame to the infractor should be closely linked to assessments of whether the rule’s purpose had been violated.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

175 volunteers (mean age = 27.3, 89 women, 40 reported no legal training) were recruited through sponsored posts and snowball sampling on social media and completed the survey.

4.1.2 Design

In a 3 (Question: text, moral, rule) × 1 between-subjects design, each participant viewed a random subset of four cases drawn from a total set of 24 cases.

4.1.3 Procedure

Each case described an incident giving rise to a rule (e.g., the accident involving a young woman texting), followed by a subsequent target incident (e.g., Felipe’s texting). For each case, participants were asked to make a single judgment, which varied by condition: in the Rule condition, after each case, participants read a statement that the agent violated the rule (e.g., “Felipe broke the law passed by Congress”). In turn, participants in the Text condition read a statement that the agent violated the text of the rule (e.g., “Felipe sent a text message while driving”). Finally, participants in the Moral condition read a statement that the agent’s behavior was morally blameworthy (e.g., “Felipe should be morally chastised for using the voice-to-text functionality of his smartphone to communicate with his friends while he was driving”). In each condition, we asked participants to report whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1: “Strongly disagree” to 7: “Strongly agree”.

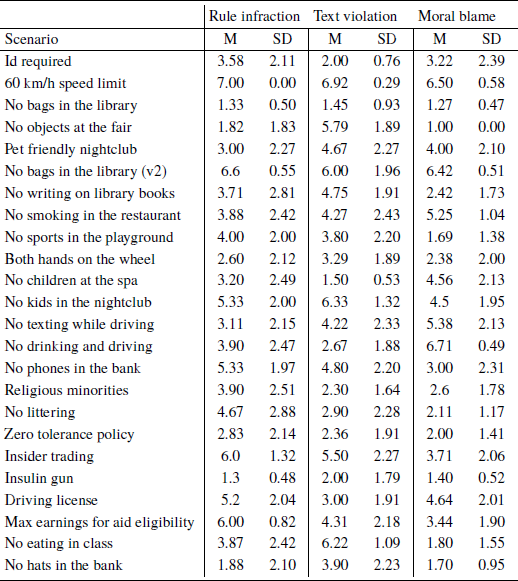

4.2 Results

To understand whether participants in the Rule condition were spontaneously incorporating assessments of the law’s text and/or the behavior’s immorality, we averaged textual, moral and rule judgments by scenario (see Table 2). In a by-scenario analysis, rule judgments correlated with both textual (r = .55, 95% CI [.19, .78], p = .005) and moral blameworthiness (r = .61, 95% CI [.27, .81], p = .002) judgments — as displayed in Figure 3. Meanwhile, textual and blameworthiness judgments were themselves uncorrelated, r = .28, 95% CI [−.14, .61], p = .19. This pattern of results held true when looking at the partial correlation coefficients (text: partial r = .50, 95% CI [.11, .76], p = .015; moral: partial r = .57, 95% CI [.20, .79], p = .005). Again, results were robust as to legal training.Footnote 15

Table 2: Rule violation judgments (y-axis) by textual (left) and moral (right) assessments. Each observation represents a scenario.

Figure 3: Rule violation judgments (y-axis) by textual (left) and moral (right) assessments. Each observation represents a scenario.

4.3 Discussion

In Study 3, textual compliance and moral blameworthiness each predicted judgments about rule infraction in a separate group of participants. Unlike Studies 1 and 2, in which textual compliance was more important than abidance with the purpose, in Study 3, the effects of compliance and blameworthiness were comparable in magnitude.

These results coalesce well with Fuller’s position. Inasmuch as this study was concerned with borderline cases, Hart could be just as willing to acknowledge the prominence of purposes as Fuller. After all, his claim was not that the “no vehicles in the park” rule’s text was always clear (as we have seen, he conceded that it was not, at least as applied to “bicycles, roller skates, [and] toy automobiles”), but only that it clearly covered certain cases (such as regular cars). Therefore, if this characteristic of Study 3’s design was the reason for the increased influence of moral evaluation, Hart can still claim to be fully vindicated by the data. If, however, the second change introduced in Study 3 — asking only one question per participant — proves decisive, Fuller might claim that moral purposes, under some conditions, are certainly more empirically relevant than Studies 1 and 2 made them out to be.

5 Study 4

Study 3 revealed stronger effects of moral-purposive concerns than were observed in Studies 1 and 2. Two methodological shifts could account for these divergent results: First, in Study 3 we asked participants to consider borderline cases rather than clear cases; second, participants in Studies 1 and 2 were asked to simultaneously determine whether the text and the purpose of the rule had been violated.

We speculated that the supplementary questions regarding moral blameworthiness and textual compliance could have modulated participants’ spontaneous concept of a rule violation. Previous work investigated the effects that questions regarding part of a concept exert over answers to a more general question regarding the same concept. Specifically, when asked to rate their marital or dating life before assessing their overall life quality, participants answered differently depending on the conversational setting introduced by researchers (Reference Schwarz, Strack and MaiSchwarz, Strack & Mai, 1991). If the questions were introduced outside of a joint evaluation context (i.e., if both questions were presented sequentially through no unifying context), participants showed an assimilation effect whereby there was a higher correlation between both answers than in a control condition. If, however, both questions were introduced by a shared prompt that made it salient that they pertained to one single conversational context, participants showed a contrast effect, whereby the correlation between questions was (non significantly) lower than in the control condition. The authors theorized that this is due to the Gricean maxim of non-redundancy: since participants have already expressed that they have a good (bad) romantic life, the remaining general question must be probing for something else that is unrelated to the first question.Footnote 16

Study 4 asked whether the differences in the effect size of purpose stem from contrast effects when textual and moral assessments are made simultaneously. Prompting participants to take into account the degree of textual compliance and purpose violation may have affected the balance of these considerations in participants’ infraction decisions — relative to spontaneous judgments made in isolation. If the rule concept is composed of both text and purpose, contrast effects are predicted by the maxim of non-redundancy: inquiring about one of the sub-elements in the same conversational context as the general rule-breaking question should make participants more likely to answer the latter based on the second, latent sub-element. To test the hypothesis of a contrast effect, in Study 4 we manipulated whether participants were asked to decide rule judgments either in isolation or while simultaneously considering its sub-elements, i.e., textual compliance and/or moral blameworthiness.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

364 people (mean age = 30, 184 women, 125 reported no legal training) were recruited through sponsored posts and snowball sampling on social media and completed the survey.

5.1.2 Design

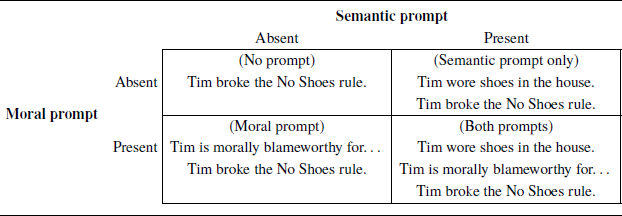

In a 2 (Case-type: overinclusion vs. underinclusion) × 2 (Semantic-prompt: present vs. absent) × 2 (Moral-prompt: present vs. absent) between-subjects design, participants viewed a battery of four clear-cut cases adapted from Studies 1 and 2.

5.1.3 Procedure

As in previous studies, participants learned about a rule, its literal wording and its underlying purpose, and were asked to determine whether a case of either under or overinclusion was in violation of that prior rule. We also manipulated whether participants were asked to make textual and/or moral judgments simultaneously. When the semantic prompt was present, participants were asked to determine whether the act violated the text of the rule. When the moral prompt was present, participants were asked to determine whether the agent’s behavior was morally blameworthy. Semantic and moral prompts were orthogonal factors, such that participants could see either, both or neither (Table 3).

Table 3: Experimental conditions in Study 4.

In every condition, participants read a statement that the agent violated the rule (e.g., “Tim broke the No Shoes rule”)Footnote 17, and reported whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1: “Strongly disagree” to 7: “Strongly agree”. Participants in the Semantic Prompt Only condition read a statement that the agent violated the text of the rule (e.g., “Tim wore shoes in the house”) immediately above or below the rule-violation statement in a counterbalanced order across participants. Similarly, participants in the Moral Prompt Only condition read a statement that the agent violated the rule’s moral purpose (e.g., “Tim is morally blameworthy for walking in the house with dirty feet”). Lastly, participants in the Both Prompts condition saw both the semantic and moral prompts, together with the rule-violation statement, in an order randomized across participants.

If moral-purposive concerns play a greater role in the spontaneous concept of a rule, participants should treat underinclusion as prohibited in the No Prompts condition — but treat overinclusion as prohibited in the Both Prompts condition. The inclusion of the Semantic Prompt Only and Moral Prompt Only conditions enables us to infer whether either prompt drives the hypothesized shift away from a spontaneous (i.e., moralized) concept of rules.

5.2 Results

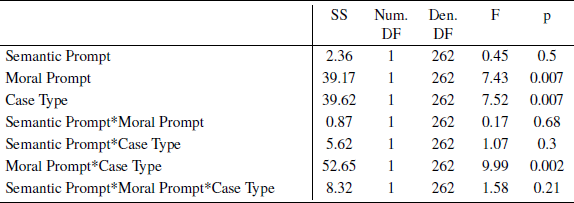

In a 3-way ANOVA, we entered Case-Type (overinclusion, vs. underinclusion), Semantic Prompt (present, vs. absent), and Moral Prompt (present, vs. absent) in the fixed effects portion of the model (see Table 4). To account for the non-independence of observations, we include crossed random effects of participant and scenario.

Table 4: Type-2 ANOVA Table with Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom.

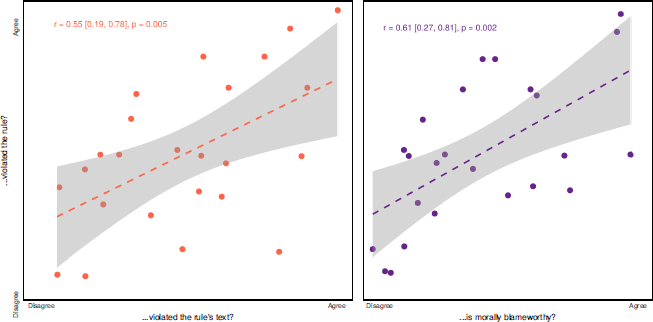

We replicated the effect of case-type documented in Study 2, F(1, 262) = 7.52, p = .007. The effect of case-type was qualified by a two-way interaction between case-type and moral prompt, F(1, 262) = 9.99, p = .002. Meanwhile, no corresponding interaction emerged between case-type and textual prompt, F(1, 262) = 1.07, p = .30. The marginal means by condition are displayed by Figure 4.

Figure 4: Rule violation judgments (marginal mean, and 95% confidence interval) in cases of under- and over-inclusion, for each of the four experimental conditions. We observe a distinction between cases of under- and over-inclusion when the moral prompt is present (bottom panel), but not absent (top panel).

Inspection of the significant two-way interaction helps to interpret the overall pattern of results: In the absence of the moral prompt (i.e., No Prompts & Semantic Prompt Only conditions), participants did not distinguish overinclusion (M = 3.46, 95% CI [3.08, 3.94]) from underinclusion (M = 3.54, 95% CI [3.15, 3.93]) cases, B = −0.08, t = −0.29, p = .99. Meanwhile, in its presence (i.e., Both Prompts & Moral Prompt Only), participants treated cases of overinclusion (M = 4.58, 95% CI [4.19, 4.97]) as rule violations more often than cases of underinclusion (M = 3.45, 95% CI [3.10, 3.81]), B = 1.13, t = 4.24, p < .001 — as in Studies 1 and 2. Again, the overall pattern of results remains the same when controlling for legal training.Footnote 18

Thus, the textualist distinction between case types appeared to arise from a contrast effect — i.e., requesting that people simultaneously assess the blameworthiness of the infraction at hand. The inclusion of the moral prompt appeared to lead participants to interpret the infraction decision as distinct from the question of moral blameworthiness — resulting in the tendency to view cases of overinclusion, but not underinclusion, as violations of the rule at hand.

Finally, we garner further evidence for this interpretation by analyzing participants’ subjective assessments. We look at the association between textual compliance and rule infraction judgments, and ask whether this association is moderated by the presence of the moral prompt. Specifically, in a two-way ANCOVA, controlling for Case Type, we enter Moral Prompt, Textual Assessment, and the Moral Prompt×Textual Assessment interaction. (Since only participants in the Semantic Prompt Only and Both Prompts conditions made assessments of textual compliance, this analysis draws on data from two of four groups.)

If a contrast effect is present, adding the moral prompt ought to strengthen the relationship between textual assessments and rule infraction decisions. Indeed, we observed a two-way interaction between Moral Prompt and Textual Assessment, F(1, 438) = 10.93, p = .001. Simple slopes analyses revealed that the effect of textual assessments on infraction decisions was larger when accompanied by the moral prompt (B = 0.70, 95% CI [0.59, 0.81], vs. unaccompanied: B = 0.45, 95% CI [0.33, 0.58]; t = −3.27, p = .001), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Rule violation judgments in overinclusion (red) and underinclusion (blue) cases, by textual (top) and moral (bottom) assessments. Left-side panels display responses from the single prompt conditions (i.e., semantic prompt only and moral prompt only), while right-side panels display responses from the Both Prompts condition. The introduction of a moral prompt strengthened the association between textual assessments and rule violation judgments. In contrast, the introduction of a semantic prompt did not moderate the association between moral assessments and rule violation judgments.

For completeness’ sake, we mirror the above analysis with moral blameworthiness as the continuous moderator: Did the presence of the semantic prompt weaken the effect of perceived moral blameworthiness on infraction decisions? This ANCOVA revealed no two-way interaction between Text Prompt and Moral Assessment, F(1, 321) = 0.88, p = .35. The effect of moral blameworthiness on infraction decisions was comparable whether accompanied by the semantic prompt or not (B = 0.41, 95% CI [0.26, 0.57] vs. unaccompanied: B = 0.50, 95% CI [0.35, 0.64]; t = −0.93, p = .35; see Figure 5).

5.3 Discussion

Study 4 yielded evidence of a contrast effect (Reference Schwarz, Strack and MaiSchwarz, Strack & Mai, 1991). Specifically, making a separate yet simultaneous moral judgment of the agent’s conduct strengthened the association between textual compliance and infraction judgments. In other words, in the absence of a moral prompt, participants spontaneously assigned greater weight to the moral-purposive dimension of rules (and as a result treated cases of underinclusion as violations to a comparable extent). Meanwhile, the presence of the moral prompt led participants to distinguish morally blameworthy agents from rule violators. In sum, when people interpret rules spontaneously, they tend to ’moralize’ the concept of rule — an effect that can be weakened by demanding that participants simultaneously reason about the morality of the putative infractor’s conduct, which leads to a stronger textualist approach to rules. This pattern of results suggests that the discrepancy between Studies 1 and 2 on one hand, and Study 3 on the other, is driven to some extent by a part-whole contrast effect of the prompt about the agent’s moral blameworthiness.

One question that might arise is that the part-whole hypothesis should predict contrast effects not only with the inclusion of the moral probe, but also (and in the opposite direction) with the inclusion of the semantic probe. We did not detect such an effect. A possible explanation is that, although composed of both textual and moral elements (a dual concept account of rules), the primacy of the textual component in the folk concept of rule is such that it overrides the maxim of non-redundancy. Instead, one hypothesis is that we should expect assimilation to be the outcome dictated by conversational pragmatics in such circumstances.Footnote 19

An alternative explanation for the effects is to do away completely with the dual concept account and maintain that the folk concept of rule is only textual, but that moral concerns often interfere with our ability to apply that concept correctly. Under this alternative account, the reason why the introduction of the moral prompt increases the correlation between textual and rule-violation judgments is that participants have been given an opportunity to vent their moral views in a way independent of their rule-violation judgments, which leaves them free to correctly apply the latter concept (see Reference Turri and BlouwTurri & Blouw, 2015; Reference TurriTurri, 2019). This explanation is consistent with our results and further research should test it.

6 General Discussion

Social life is characterized by the ubiquitous presence of prescriptive rules of all kinds — e.g., legal, etiquette, moral, political, and so on. From the simple “no shoes in the house” rule to the highly institutional governmental rules prohibiting insider trading, what all of them have in common is that they exist in the hope of exerting pressure in the world, by guiding judgments and channeling behaviors. As long as we are dealing with non-ultimate linguistic prescriptions — i.e., those rules that aim at achieving background purposes and are communicated through language — there remains the question characteristic of the Hart-Fuller debate: Is a rule its textual formulation understood according to its ordinary meaning, or is a rule first and foremost the background moral purposes it aims at achieving? From their armchairs, philosophers have advanced many different competing theories about the nature of rules. However, what do non-philosophers — those who are the target of rules in their daily lives and operate with and under rules — actually believe them to be?

In this paper we embrace the experimental turn in order to answer the age-old question about the concept of rule, trying to capture its ordinary meaning and seeing which philosophical theory would be vindicated by the results. We find that, for both legal experts and non-experts, both text and purpose are relevant components of rules (legal or otherwise). Even though both components are relevant, our evidence points to a predominance of text over purpose in people’s understanding of rules.

The main reason for the primacy of text has been noted by psychologists, rule consequentialists in normative ethics, as well as by some legal scholars working on the nature of rules. As discussed in the introduction, rules that are applied according to their text (assuming that their text is reasonably determinate) are more prone to achieving certain objectives: predictability, certainty, coordination, decision-making efficiency, and avoidance of moral errors due to complex moral reasoning. Some research suggests that many times we are better at pursuing outcomes indirectly, through clearly expressed rules that are followed according to their text, than trying to get at these goals directly (Reference Gigerenzer, Todd, Gigerenzer and ToddGigerenzer & Todd, 1999; Reference Gigerenzer, Engel, Gigerenzer and EngelGigerenzer & Engel, 2006; Reference SchauerSchauer, 1991). This could explain why people have taken the stance of acknowledging text as a major component of the concept of rule through and through our set of experiments.

However, text is not the only relevant feature of rules. To a lesser, but significant extent, participants also feel that purposes matter when making judgments about rule violations. There are two ways to conceptualize this finding. Previous work (Reference Turri and BlouwTurri & Blouw, 2015; Reference TurriTurri, 2019) dealt with a similar phenomena by assuming that the concept of rule is entirely determined by the rule’s text, but that our ability to correctly apply this concept might be affected by our moral commitments. So, when someone blamelessly violates a rule’s text, we feel the temptation to excuse them and respond that there was no rule violation not because they did not violate the rule, but because we are conflating two different speech acts: one purely descriptive that states the fact that they violated the rule and another one normative that states that they should be punished. This account is compatible with our results. It might be the case that the folk concept of rule is entirely textual, but that our capacity to correctly apply this concept is mitigated by our normative commitment not to blame people who did nothing wrong (and, on the other hand, to blame people who did something wrong despite complying with the text).

A different way to make sense of our results is to hypothesize that the concept of rule is composed of at least two elements: one textual and descriptive, the other purposive and normative. Under this account, it is not the case that we have a capacity to apply a descriptive concept that is biased by the confounding demands of morality. In effect, the concept of rule itself — like many others (see Reference KnobeKnobe, 2010) — would host these different components. Both interpretations fit the data well. Future research should design novel experiments to tease apart these different theories about the concept of rule.

6.1 Implications for legal theory

If the strong view attributed to Fuller by Schauer according to which it is “never possible to determine whether a rule applied without understanding the purpose that the rule was supposed to serve” (2008, p. 1111) hinges on people’s actual beliefs and attitudes, then it is clearly at odds with the present evidence. Oftentimes people are willing to say that a rule was violated even by behaviors that do not hinder the rule’s explicit purpose at all. There do seem to exist “(…) some possible rules in some possible legal systems that can be identified as legal without resort to moral criteria” (Reference SchauerSchauer, 2008, p. 1113), a point in favor of Hart’s conceptual positivism.

Hart’s views are also only partially vindicated. Even though people drift towards a more textualist view on joint-evaluation, they remain susceptible to moral concerns through and through. The fact that moral and purposive concerns are just as important in determining people’s spontaneous grasp of rules might pose a challenge for Hartian positivism to the extent that it is concerned with accurately describing the attitudes that laypeople, who presumably engage with law intuitively, have towards legal rules. If this is the case, positivist theories may not always be as accurate as natural law in explaining the way people ordinarily conceive, or reason about, the law.

Rather, our data suggest that the concept of law reflects both a preferential concern for the legal text as claimed by positivists, and a default sensibility towards the purpose of law, as argued by Fuller. In many circumstances, people’s understanding of whether a rule is broken is spontaneously informed by both concerns. Yet, we also found evidence that, upon concerted consideration, people were more likely to distinguish morality and law, resulting in a positivist understanding of the concept of rule.

Our results trace the psychological fault lines of the Hart-Fuller debate. It is possible that the philosophical styles of Hart and Fuller could explain their different views about the concept of rule and the perennial character of their debate. Hart was the analytic philosopher par excellence and the methods of analytic philosophy emphasize the decomposition of concepts. Therefore, one could speculate that Hart and other analytic philosophers, who succeeded him and held similar views, are prone to decompose multifaceted concepts into their constitutive sub-elements, thus privileging text. On the other hand, as noted by Schauer, “Fuller’s philosophical forays were far clumsier” (2008, 1132). This more holistic, and less analytic, approach to legal reasoning may have contributed to Fuller’s predilection for purposes.

If contextual factors play this critical role in rule infraction judgments, maybe we should move away from general jurisprudence (which makes claims about essential features of law in all possible legal systems and worlds) to particular jurisprudence (which makes claims about localized legal systems). If people in different cultures and contexts conceive rules in different ways, carving out the interplay between text and morality in distinct manners, then their very concept of law may be different. Big general claims about the empirical, even if not conceptualFootnote 20, descriptive correctness of positivism or natural law should be informed by the experimental findings of particular jurisprudence.

Finally, law is a socially constructed concept (Reference HartHart, 1994; Reference SchauerSchauer, 2005; Reference SearleSearle, 1995). As such, people may be able to promote their preferred concept by shifting the conditions under which others engage with rules. Aware of our results, those who are optimistic about a morally infused concept of law may wish to encourage the spontaneous point of view, while those who are not stand to benefit from fostering a more analytic perspective on rules.

6.2 Limitations and future work

The experimental research we conducted has several limitations that should be taken into account in discussing its implications for general jurisprudence. The first of such limitations is the extent to which our results generalize across languages, cultures and jurisdictions. After all, we conducted our studies in Portuguese, and a vast majority of our subjects were Brazilian. Perhaps, our particular pattern of results reflects a quirk of Brazilian legal culture, or of certain kinds of legal systems (i.e., civil law systems), and only future cross-cultural studies will tell if they are representative of legal reasoning more broadly.

Another limitation is that, inspired by Schauer, we set out to experimentally examine rules not only in law, but also in life. As a result, several of our examples dealt with non-legal rules, such as the no-dogs, and the no-shoes rules. Positivists may very well say that this reduces the import of our results to their theory. After all, exercising one specific and particularly stringent form of authority is the distinctive way law works. Other normative systems need not be so stringent and can live with looser, more moralized concepts of rule. In fact, post-hoc analysis of Study 3 data, classifying our rules as legal or non-legal showed that people might in fact think differently about legal rules.Footnote 21 In any event, future research should test in a controlled setting whether or not judgments about legal and non-legal rules differ.

Another valid objection deals with the relationship between a rule’s purpose and overall morality. In the first two experiments, we asked whether each case impinged on the purposes of the relevant rule (i.e., was the animal/object a nuisance to the clients of the restaurant?). In Studies 3 and 4, in contrast, we asked whether or not rule-breaking agents were morally blameworthy. These two questions are not necessarily the same. Imagine a group of lawyers who think that a rule’s purpose has precedence over its text, but that overall morality should have no influence over the law. They think, for instance, that the truck-turned-monument proposed by Fuller should be allowed in the park because the park’s rule’s purpose is to avoid accidents and a stationary truck poses no such risk. If they are committed to this specific underlying purpose, but not to overall morality, they should object to the passage of an ambulance through the park: even though letting the ambulance through might be the right decision all things considered, it certainly increases the risk of an accident inside the park. By design, we surveyed cases where (to our eyes) both specific purposive reasoning and general moral reasoning recommended the same result — and sought to collect data on both tasks. On the other hand, we are left with a diffuse understanding of how natural law considerations play into processes of legal cognition. In future work, we hope to distinguish whether the ordinary concept of rule spontaneously incorporates either (1) concerns with doing the best thing all-things-considered (Reference De Freitas, Tobia, Newman and KnobeDe Freitas et al., 2017), or (2) a preoccupation with the specific underlying purposes (2a) ascribed to or (2b) intended by the rule (Reference Rose and NicholsRose & Nichols, 2019), or else (3) some special moral domain unique to legal systems in general (the Fullerian view) or in particular (see Reference WaluchowWaluchow, 2007).

Finally, different agents might engage with legal rules under very different circumstances. Think of the rules prohibiting dogs in restaurants. The restaurant’s maître d’ has to decide whether a man carrying a cat will be allowed in the restaurant even before he gets a table. If the cat later makes a mess, the restaurant owner or even a judge, if the case somehow ends in court, will have to decide whether the maître d’ should have allowed the customer with the cat according to the rule. People in different roles may have a different take on what makes a rule while occupying these different positions. This calls for a more nuanced “perspectival theory of law” (Reference Sinnott-ArmstrongSinnott-Armstrong, 1999).

In line with this, ongoing work (Struchiner, Almeida & Hannikainen, in preparation) shows that legal judgments about rule violation are subject to the abstract/concrete paradox. Maybe fact-finding judges and law enforcement agents hold the purpose to be more important insofar as they are exposed to the case’s concrete facts. Appellate judges, for instance, might be more inclined to adopt a textualist view of rules, in part as a result of the abstraction with which legal cases are brought before them.

Alternatively, judges and law enforcement agents might tend more closely to the textual features of rules insofar as they are accountable to higher authorities. It seems intuitively easier to justify strict adherence to a law’s text than to defend one’s purposive interpretation of a law and its relation to the concrete case at hand. If this is the case, then we should expect that decision-makers may exercise the freedom to moralize legal rules when making definitive or autonomous rulings — i.e., that will not be subject to further oversight — but stick closely to a rule’s text when issuing provisional or highly scrutinized decisions.

7 Conclusion

After 60 years of speculation, the Hart-Fuller debate needed to leave the armchair. In a series of four studies, we have tried to draw the psychological fault lines of the philosophical divide. We have found that people’s judgments about rule violation are influenced by both textual and moral-purposive considerations. At a broad level, this dueling aspect of the concept of rule leans Hartian, as text is often sufficient to determine whether a rule was broken. However, this tendency appears to be weaker when participants reasoned spontaneously about a series of putative infractions. In these contexts, participants show a greater comparative concern for broader moral purposes beyond the text.

These findings represent an important step toward understanding people’s intuitions regarding rules, legal and otherwise. Much remains to be done both conceptually and experimentally: First and foremost, subsequent research should survey people from diverse legal and cultural backgrounds to understand whether our results generalize. Moreover, more data need to be collected on legal and non-legal rules to determine whether or not legal status matters with regards to the influence of text and purpose. We also need to tease apart purpose and morality to understand what drives the normative component of a rule. Finally, different roles might privilege different aspects of the concept of rule.