All sounds deserve recognition. This article recognizes, measures, and celebrates a decidedly subtle one: a single, audible breath taken by Dashon Burton two-and-a-half minutes into his recording of the song sermon “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.”Footnote 1 Perhaps best known as a founding member of the vocal octet Roomful of Teeth, Burton is a multi-Grammy Award-winning American opera singer, soloist, and arranger.Footnote 2 His unaccompanied version of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” appears on his 2015 album Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome.Footnote 3 Like all memorable musical experiences, this quietly transcendent moment of narrative breathing owes its impact to both micro- and macro-histories. On the smallest scale, Burton's breath has a local function as an interstitial event between two sung lines of melody; on the largest, it enacts a process by which a piece of American music is created and disseminated through singing, notating, and recording. This study places the poignance of Burton's audible breath within the context of earlier published versions of the song, as well as within the musical flow of his interpretation. My emphasis on the micro-temporal listening experience acts as an intentionally slowed-down documentation of Burton's singing, his breathing, and the interaction between the two. When his recording is viewed at high resolution, it is less a matter of interaction than integration: his breathing is his singing.

Burton recorded “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” on the stage of the Concert Hall at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey on August 22, 2013. According to Burton's sound engineer, Loren Stata, the singer was standing stage left, with a piano to his right; the piano was not used on this track, but remained in place as the session mainly involved Burton singing songs with pianist Nathaniel Gumbs.Footnote 4 Burton's voice was preserved by a set of six microphones: a pair of Milab DC-196 microphones (set to cardioid) were placed about a foot behind his music stand; for the main room sound, a pair of Schoeps Mk2S microphones were spread three feet from one another on a high stand behind him; finally, alternate room sound was captured via an AEA r88 stereo Blumlein ribbon microphone placed at center stage. Stata edited the audio using the sound engineering software Magix Sequoia 12, and reports that the seamless-sounding track actually includes six edit points.Footnote 5 A photograph from the recording session, which shows Burton reading from his iPad score in front of the Milab microphones, is seen in Figure 1. Stata vividly recollects the recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word”: “This was the last song recorded, over two days of sessions. We recorded two full runs, and a last half. This was one of those moments in my recording life—Geoffrey [Silver, the session producer] and I looked at each other and mouthed ‘wow,’ unwilling to break the silence at the end.”Footnote 6

Figure 1. Dashon Burton at the recording session for “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” in the Concert Hall at Drew University, Madison, New Jersey, on August 22, 2013. Photograph © Geoffrey Silver, Acis. Used with permission.

What is the source of Stata's “mouthed ‘wow’”? Or, for that matter, of my own? It is undoubtedly a response to the elements that critics might cite in their praise of Burton's performance: his tone, his phrasing, and his combination of power and restraint while singing of a brutal killing. But there is more to the recording than the sung notes. Singing is a highly specific form of breathing out. Each sung phrase is made possible by an unpitched inhale, and every melody in Burton's unaccompanied recording is, at a fundamental level, an intoned exhale. Inhales are, in every sense of the word, the unsung partners of heard melodies. The simple delineations of “inhale” and “exhale” do not tell the full story, as each of these actions can occur in a wide variety of types: inhales can be drawn, gasped, gulped, sucked, sniffed, and taken; exhales can be expelled, expired, exuded, given, huffed, issued, or vented. Either can be secretly or prominently sounded, and when they are heard, their duration carries narrative information. We can be certain that every performer is breathing when they make a recording; whether or not sound engineers edit them out is another matter. In either case, listeners can be sure that there were breathing sounds intertwined with the melodies emanating from the voice and making those very melodies possible.

This paper documents Burton's recording as an American artwork in and of itself, and not simply a token of a governing “score.”Footnote 7 In discussing this specific instantiation of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word,” it is neither expected nor assumed that Burton sang the work in an identical fashion at any other time, whether recorded or not. Building upon Nicholas Cook's recommendation that musicologists “exploit the potential of sound recordings as documents,” the following close reading uses Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” as a case study of the interaction between sung notes and audible breaths, and the ways in which both work together in the expression of a lyric.Footnote 8 Acknowledging its relationship to earlier notated arrangements by J. Rosamond Johnson, William Arms Fischer, John W. Work, and Roland Hayes, Burton's recording is treated as its own artwork. This study moves from the song's history, lyrics, and structure, to the durations of Burton's sung syllables and, finally, to his individual audible breaths. The last of these, the solemnizing breath that inaugurates the fifth stanza, is pinpointed as the narrative denouement in Burton's version of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.”

Breaths as Music: Corporeal Liveness versus “Intelligent Suppression”

Should breath sounds count as music? At the current historical moment, the answer is genre- and instrument-specific. Audible breaths are perfectly acceptable when they are notated by the composer, as in Caroline Shaw's “Courante” from Partita for Eight Voices.Footnote 9 Likewise, recordings of wind instruments—such as Claire Chase's celebrated recording of Varèse's solo flute work Density 21.5—are replete with sounded inhales.Footnote 10 The matter seems most settled, and most sonically integrated, within popular music. This is no doubt aided by the genre's practice of placing the microphone close to the singer's mouth, as well as its lack of notated scores which might tacitly (even insidiously) prescribe what is, and what is not, “the piece.” Jennifer Iverson makes the point in her discussion of Björk's “Ancestors,” when she classifies Björk's audible breathing—which she deems “wheezing”—as the sonic foreground: “Should this wheezing be musical? The piano sounds in accompaniment, as if a person having an asthma attack is exploring the piano.”Footnote 11 Commonplace elsewhere, the acceptability of breaths-as-music is less resolved within studio recordings of the so-called “classical” vocal artists such as Burton, whose recorded repertoire includes art songs, lieder, Spirituals, and avant-garde compositions. Within the genre of song sermons, the audibility of breath—no doubt expressive and (to some) desirable—is generally absent from musicological or theoretical scholarship.Footnote 12 This article is designed to change that; it elevates the sound of Burton's breathing as co-equal to the notes and lyrics with which they are expressively intermingled.

Disciplines need to be reminded of what, and whom, they exclude. What counts as music (and who does the counting) deserves a reckoning, and I am inspired to ask these questions by Ellie M. Hisama, who asks them of music theory, and by Sarah Ahmed, who directs them at institutional hierarchies.Footnote 13 Once breath sounds have been elevated to the same level as the melodies that surround them, the expressive importance of such “extraneous” sounds can be theorized. One of the first to do this was Paul Sanden, who wrote about a recording's “corporeal liveness,” which he defines as “liveness invoked by music's connection to an acoustic sounding body, usually that of a human performer.”Footnote 14 One of the focal points for Sanden's arguments is the recorded oeuvre of Glenn Gould, whose creaking chair sounds and audible singing contribute to a vivid corporeal liveness.Footnote 15 In later writings, Sanden refines his categorizations to include “liveness of fidelity,” wherein “the further a recording or performance deviates from ‘true’ (acoustic) performed sounds, the less live it is.”Footnote 16 Stata's sensitive engineering of this performance of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” preserves many of Burton's most intimate vocal sounds, including the opening and closing of the singer's mouth. This recording thereby exhibits a high degree of Sanden's “liveness of fidelity.”

Not everyone is comfortable with breath sounds as music. Producers, recording engineers, and performers have seemingly joined forces to present recordings where, for the most part, breath sounds are minimized. In doing so, they have established a practice that enacts the audio equivalent of Photoshop editing. Influenced by both the market and the undue hegemony of a Western European “sanctity” of the composer's score as determinative of “meaningful” content, the recording industry often caters to the belief that consumers desire the nullification of the sounds made by the body of the performer. Consumers are evidently expected to want recordings to be audio representations of the songs listed on the album cover, presented via the interpretive lens of the performer often pictured there, but without the “intrusion” of the bodily sounds that might have been heard if the listener was actually in the room with the musician at the moment of recording. Sounds of inhaling and exhaling are often surgically deleted by audio editing software. In their textbook on sound engineering, James Angus and David Howard place the so-called “breath noises” alongside “key clicks and page rustling” in the category of “extraneous” sounds that are ripe for removal from audio tracks.Footnote 17 To be sure, a loud page-turn or prominent key click might be unwanted by an artist or engineer, but why is the sound of a musician breathing so offensive? The singer is undoubtedly inhaling and exhaling when they are making the recording. Why then is their breathing subject to removal? When Angus and Howard categorize breath as “noises,” they enforce a separation between “music” and “noise” which has a long and contentious history within musicology, theory, and the wider listening audience.Footnote 18 A welcome and contrasting view, which acknowledges the expressivity of corporeal liveness, is provided by Jennifer Judkins: “Musical sounds are generated through rhythmic physical motions or air pressure applied to an instrument, and instruments (and humans) are noisy things.”Footnote 19 Quelling such “noises” is a lucrative business: one of the most widely used audio restoration software suites—Izotope's RX 7, released in September 2018—offers a “breath control module plug-in” that “reduces tedious, seek-and-destroy editing to one click with intelligent suppression.”Footnote 20 It seems disturbingly Orwellian to apply the phrase “intelligent suppression” to an automated process that erases the sound of someone breathing.

Documenting and advocating for the expressive content of Burton's breath and mouth sounds generates a fruitful analogy with the psychological category of micro-expressions. The topic originated with the research of Haggard and Isaacs, and was later popularized by a series of books by Paul Ekman.Footnote 21 According to Ekman, micro-expressions—and the related categories of “slight” and “partial” expressions—are the facial gestures that we unconsciously witness, or make, when listening or speaking.Footnote 22 Such rapid facial motions deliver expressive and often crucial information that would not be recorded in a written transcript of a given conversation. Burton's breaths fall into a similar category of sounds that we might overlook (or “listen past”), but that we nonetheless hear. Just as facial micro-expressions offer valuable and often revealing information that enhances the meaning of spoken words, the placement and duration of Burton's breaths provide audio traces of physical activity. A more complete picture emerges when we rescue the act of listening from the implied admonitions that such sounds are—in the unsettling language of Izotope's audio editing software—candidates for “intelligent suppression.” Indeed, the Magix Computer Products International Company—makers of Magix Sequoia 12, the audio engineering software Loren Stata used to record and edit Burton's performance—has its own unsettling name for their proprietary breath-suppression tool: “Spectral Cleaning.”Footnote 23

Contrary to this ethos of automated, “one-click” silencing, I claim that the most pivotal, knowing, and emotionally intense moment in Burton's three-and-a-half minute recording is not a climactic high note (of which there are none), or a moment of exquisite vibrato (of which there are many), but a single audible intake of breath, one of thirty-five such inhales across the entire track. This level of sonic documentation draws an analogy with the U.S. Census, which is in progress as I write. The Census must necessarily make “an ‘actual Enumeration’ of each state's population”; using this data, informed political decisions may be made.Footnote 24 By analogy, most studies of recorded sound focus primarily on the notes being sung, and occasionally on their rhythm. All other sounds, including mouth and breath sounds created by the singer, are either unconsciously overlooked or consciously ignored. Important detail is lost when such sounds are not counted, and removing or suppressing them deprives the listener of unique types of intimacy and musical understanding. Consciously or not, we hear breaths; we register when they appear and when they subside, and their presence is integral to the interpretive act we engage in when we listen. In the case of Dashon Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word,” recognizing breath sounds as integral to the singing unlocks deeper levels of the recording's expressive content.

When audible breath sounds have found their way past sound engineers and onto commercial recordings, scholars and critics have often derided them as unfortunate and inappropriate. Such attitudes extend back to the origins of the medium of recorded sound itself. Herman Klein's otherwise sterling 1929 review of Lotte Lehmann makes the point, explicitly: “Every sound stands out in bold relief; every syllable, every murmur, every tiny utterance, down to the particular sound whereof one would willingly hear less—I mean the constant hiss of the intake of breath—the only blemish upon the perfection of an exquisite achievement.”Footnote 25 According to Klein, Lehmann's recording is “perfection,” albeit one marred by a single “blemish”: the hiss of her inhales. It often falls to scholars outside of music to remind our field of its prejudices, sonic and otherwise. Kimberly Bain, whose interdisciplinary dissertation “The Theory and Praxis of Black Breath” engages with the interaction between music and race, emphasizes that all recorded vocal sounds are expressive.Footnote 26 In a 2017 presentation, Bain singled out the role of breath in Rashida Bumbray's performance of “Lay Down Body” in the video version of Common's “Black Again America (featuring Stevie Wonder).”Footnote 27 Speaking of Bumbray, Bain writes:

She bears the heavy emotional toll required to perform, and it's audible. As she oscillates between call and response, she begins to run out of breath; words gaining a breathless quality. And then she gasps: in her second repeat of the chorus, between the phrases ‘Lay down’ and ‘Lay down, body,’ she destabilizes the rhythm of the song with a gasp for air.Footnote 28

Music studies can learn a great deal from Bain's sensibility, in which there is no boundary between the notes that Bumbray sings and the inhales on which they rely.

Jonathan Dunsby has called upon the field of music studies to pay closer attention to the expressivity of audible breaths.Footnote 29 The source of Dunsby's position is circuitous, but bears excavation. It originates with Roland Barthes's bold statement about sound in cinematic film:

In fact, it suffices that the cinema capture the sound of speech close up (this is, in fact, the generalized definition of the ‘grain’ of writing) and make us hear in their materiality, their sensuality, the breath, the gutturals, the fleshiness of the lips, a whole presence of the human muzzle (that the voice, that writing, be as fresh, supple, lubricated, delicately granular and vibrant as an animal's muzzle), to succeed in shifting the signified a great distance and in throwing, so to speak, the anonymous body of the actor into my ear: it granulates, it crackles, it caresses, it grates, it cuts, it comes: that is bliss.Footnote 30

Dunsby throws down a gauntlet to current musicology: redirecting Barthes's words toward the analysis of audio recordings, he characterizes close listening as valuably discomforting. Recognizing and celebrating the totality of each grainy, vocal, human sound “may make us squirm, may render us coyly objective, it may be that post-structuralist criticism knew something which current musicology would do well to reinvent for itself.”Footnote 31 Cinematic sound brings the listener not only closer to the declaration, but closer to the mouth of the declarer. Transposed onto music, Barthes's image implies a microphone embedded in the “le museau humain” (the human muzzle), the part of the face including the nose, mouth, and jaw. This microphone picks up every tick of the tongue against the teeth, every glint of saliva between the lips, and the toned and untoned sound of the words that flow through this area, be they sung or spoken. To be sure, “muzzle” has several meanings, some more disturbing than others, including: as a noun, a covering for the mouth used to prevent biting, something that prevents expression, or the open end of an implement such as the discharging end of a weapon; as a verb, to gag, restrain, or restrict. Though such meanings resonate frighteningly within America's history and politics, I seek to retain Barthes's term here in its primary sense as a physical descriptor. I was initially resistant to Barthes's equating of the singer's muzzle to that of an animal's; however, the extraordinary beauty and complexity of both human and animal mouths are natural, fascinating, and praise-worthy: my own muzzle is a place of interest as a locus of my speaking and singing, as is Burton's. Audio recordings such as Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome provide listeners with rich traces of muzzle- and lung-based activity: not only preserving notes being sung in certain rhythms, but capturing glottal stops, plosive pops, and the audible sounds of breathing.

Like Bain, Barthes is not celebrating breath-as-breath, but breath-as-music. Discussing a recording by the Swiss baritone Charles Panzéra, Barthes writes: “All of Panzéra's entire art, on the contrary, was in the letters (simple technical feature: you never heard him breathe but only divide up the phrase).”Footnote 32 The distinction is telling, and Dunsby once again steps forward to refine Barthes's attitude, arguing that “One would think that breathing can itself be part of the ‘grain.’ Yet [Barthes's] inflection seems to reinforce how meticulous a theorist Barthes is in demanding a corporeality in which breathing is heard only when assimilated in the poetic diction.”Footnote 33 The point proves useful: it is not the case that we hear Dashon Burton “breathe” and then “sing”; the two are intertwined. Bringing the Bain/Dunsby/Barthes perspective to bear on Burton's recording, I seek to document precisely how—rhythmically and sonically—his audible breaths are a part of the phrasal and lyrical content in which they are embedded. To be sure, Burton's recording is not a showy, noise-forward audio document, nor is it a locus classicus of high-resolution, ASMR-level mouth sounds. As captured by the microphones in the Drew University Concert Hall, Burton's sounds are restrained, controlled, even reserved. His reserve, however, heightens the narrative power of his audible breathing and mouth sounds.

The Origins of Burton's Version

Of the twenty-two tracks on Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome, “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” is the only one that Burton arranged himself.Footnote 34 Although Burton created no authoritative score for his own solo version, he owes a debt to the great American tenor Roland Hayes (1887–1977), who performed the song sermon in recitals, popularized it in recordings, and published his own score of it in My Songs: Aframerican Religious Folk Songs Arranged and Interpreted (1948).Footnote 35 Prior to its inclusion in Hayes's collection, published scores of the work include arrangements by J. Rosamond Johnson (1925), William Arms Fischer (1926), and John W. Work (1940).Footnote 36 Far from being a simple collection of varied folk songs, Hayes's collection organizes and annotates thirty of his own arrangements into three cycles of ten songs each. Hayes calls each grouping a “panel”; each panel is prefaced by a contextualizing essay, and each song within the panel receives a short written introduction, placing it within the larger dramatic and liturgical arc. While the versions by Johnson, Fischer, and Work are for piano and voice, Hayes's version—seen in Figure 2—is unaccompanied. Hayes connects the songs in his collection thematically and musically, a practice exemplified by his dovetailing of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” with the surrounding songs in its panel. It appears as the eighth song in panel three, and thereby acts as the antepenultimate song in his entire collection.Footnote 37 In Hayes's hands, “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” is part of a religious, quasi-liturgical, through-composed arrangement. Burton's recorded version has a lengthy evolution that includes a pivotal intersection with Hayes: the influence seems to have been primarily via Hayes's score, rather than from his celebrated recordings of the work. For example, Burton does not replicate Hayes's elongated ‘n’ and ‘m’ sounds on the words “never,” “not,” and “mumberlin’,” all of which can be heard on Hayes's seminal mid-twentieth-century recordings.Footnote 38 In this way, the development of Burton's version illustrates that the pathways of influence within Spiritual singing are both aural and written.

Figure 2. Roland Hayes's arrangement of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” from My Songs: Aframerican Religious Folk Songs Arranged and Interpreted (1948). Public domain.

Hayes's annotations for “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” are both musically and personally revealing. He writes: “In respect to both its music and its marvelous words, this song is a master work among all Aframerican religious folk songs. It definitely was the creation of an African who came to these shores already an accomplished bard. This particular version is a song sermon, emphatically a solo. He whom this poet-musician so poignantly reveres in this song is the only being he would call master.”Footnote 39 Hayes's lauding of the “bard” who created “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” has a strikingly personal dimension: writing in The Black Perspective in Music in 1974, Warren Marr II records an origin story that places Roland Hayes himself in the lineage of the song's creation, as the grand-grandson of its composer. Marr writes:

In 1926, Hayes went back to Curryville, Georgia, and bought 600 acres of the former 1500-acre farm where his mother had been a slave. By chance, he met Horace Mann, the son of her former owners, who was said to be 105 years of age. Mr. Mann and his wife were sick and in abject poverty. Hayes fixed a small house on the farm and moved them in. Mr. Mann told Hayes of his [Hayes's] great-grandfather. The African had been a tribal leader. In the United States he became a Christian and a creator of songs, one of which became known around the world.Footnote 40

This statement is followed directly by the printed lyrics of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word,” implying that Hayes—one of most celebrated tenors of the twentieth century—was a direct descendant of the song sermon's composer.Footnote 41

Burton's history with “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” includes a pivotal interaction with Hayes's score, but the story does not begin there. Burton first heard the song performed at a student concert during his first undergraduate year at Oberlin (2003–04) and recalled the experience vividly:Footnote 42

I didn't know the singer, because I was a transfer and I was very shy and that was my second week, maybe, so I actually don't remember who sang it. But the person who sang it—I'd never heard the song before—he just destroyed me. It was fairly ornamented and Rihanna-fied and really kind of soulfully sung in a very unique-to-him way, so I think that was a big part of it. But the melody, too, it just grabbed me immediately. So that was the first time that I heard this song.Footnote 43

Burton did not sing the piece himself until years later, and then only in a version for multiple voices. While a member of the vocal ensemble Cantus, Burton recalls his friend, the tenor Shahzore Shah, presenting Hayes's score to the group.Footnote 44 Shah confirmed that he introduced Hayes's 1948 notated arrangement of “He Never Said A Mumberlin’ Word” to Cantus for the ensemble's Independent Voices program, in preparation for their 2006–07 season, and that they began performing it in the Spring of 2007.Footnote 45

Burton's own unaccompanied version took shape years later, in 2009–11, while he was earning a Master of Music degree at the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale University. While he credits Shah for introducing him to Hayes's arrangement, Burton's recorded version differed from all those that he had heard (or read) before:

What I definitely had in my ear, as much as I do love the Roland Hayes version, was closer to the version that we did in Cantus. But even still, I sort of strayed from what we did there, certainly from the Roland Hayes and certainly from the notated version of the Roland Hayes, and then also from the first time I'd heard it in this very florid style. So it felt very individual in those terms, but in the context of how I presented it in the programs and the maybe twenty to thirty times that I'd sung it up until that point in solo programs.Footnote 46

Burton's reflection reinforces the celebrated and ongoing tradition of individualized versions within the tradition of Spiritual singing. Tammy L. Kernodle has called Spirituals “a praxis of Black postmodernism.” She illuminates their role at the core of Black concert artists’ repertoires and as the basis for compositions by Undine Smith Moore (1904–89), Margaret Bonds (1913–72), and Julia Perry (1924–79), among others.Footnote 47 Rather than being re-performed as static emblems of the past, Spirituals are regularly refashioned to create varied expressions of contemporary lived experience. Writing about the nomenclature used for such constantly evolving works, Kernodle relates that “[Undine Smith] Moore refused to use the word ‘arrangement’ to describe these settings. Instead, she called them ‘theme and variations,’ stating that her compositional intentions were not to ‘make something’ that was better than what was sung in the fields, churches, and homes, but to mine what she believed to be the intrinsic beauty of Spiritual melodies.”Footnote 48 While both Hayes and Burton describe their versions of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” as “arrangements,” each musician personalizes the material in accordance with his own expression, as Burton makes clear: “In terms of the kernel of what this song is, to me, really: it is an offering. It's an offering and it's a statement of my gratitude for my own tradition and for my own corpus of work, and for the coterie of people who have raised me in every possible way.”Footnote 49 Burton's recording mines the intrinsic beauty of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word,” drawing from his own sensibility and from the variants that he encountered over a decade of listening and singing, a trajectory that includes his first encounter with a “Rihanna-fied” variation at Oberlin, his introduction to Hayes's 1948 score when he sang with Cantus, and finally the unaccompanied recording that Burton made at Drew University on August 22, 2013.

The Lyrics: Content and Resonances

Transcriptions into standard notation of recorded music invariably fail to represent numerous salient and expressive details of the sound, and the same holds true for transcribed lyrics. Following Cook's recommendation to treat recordings “as documents,” every effort has been made to consider precisely what Burton sings on this track in an effort to honor the details that make the recording expressive. Before studying the pitches and breath sounds, it is necessary to clarify the precise lyrics of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” as sung by Burton on Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome, as Burton's sung lyrics differ both from Hayes's 1948 score and, notably, from the liner notes that accompany Burton's own disc. Burton's liner notes seem to reprint the lyrics from Hayes's score, even as he does not sing them. Below is a transcription of the complete lyrics as Burton recorded them; I have kept editorial punctuation to a minimum in an effort to stay as close as possible to the sung text:

The poetic form of these twenty-five lines is structured around a series of changing, intensifying actions, each of which is answered by resolute, meaningful muteness. Purposefully leaving aside the religious connotation of the song as a portrayal of the crucifixion, the actions of the five stanzas relate the story of a man being killed, and the first lines of each stanza present the death scene as a series of five related, escalating actions: (i) feeling, (ii) nailing, (iii) piercing, (iv) bleeding, and (v) bowing/dying. These stages summarize the trajectory of the narrative, whose developing story of torture and death is answered at every turn by a powerful non-action: the steadfast silence of the dying man. The poetic form of the lyric draws its power from the tension between an intensifying arc of violence and the dying man's repeated reaction of non-violent stoicism. The pronouns in each stanza draw a narrative trajectory that plays out across Burton's performance. Taken as a whole, the lyric posits four agents: the narrator, those listening to the narrator, the killers, and the man being killed. These four groups—narrator, listeners, killers, and killed—are invoked differently across the five stanzas. Stanza one includes no pronouns; it simply states that the scene is, unequivocally, “a pity and a shame.” Stanzas two and three shift the focus to the killers themselves. The plural pronoun “they” which begins stanza two simultaneously instantiates the existence of both the violent actors and the narrator-as-onlooker; the narrator stands separate from the violent acts and reports them. The opening line of stanza four withdraws again from pronouns, and centers on the body of the dying man. The “twinkalin’” of the blood is described factually, recalling the earlier “pity” and “shame.”Footnote 50 Stanza five (“He bowed His head and died”) culminates the lyric and focuses the gaze. It demonstrates the outcome of the preceding violence: nailing, piercing, and bleeding have brought about dying.Footnote 51 This final stanza also resolves the pronoun conflict that has marked those before it. Stanza five refers neither to the killers (“they”), nor the listeners, nor the narrator; the entire drama converges on the man who is dying and, by the end, has died.

As seen in Figure 2, the dramatic form of Hayes's arrangement centers on his unique setting of stanza three (“Dey pierced Him in de side” in Hayes's version of the lyric). After establishing a repeating melodic structure in stanzas one and two, stanza three presents a divergent melody and a truncated lyric structure. In this central stanza, Hayes prevents the melody from reaching the highpoint of the first two verses, and likewise shortens the lyric. While all the other verses rise up to a notated D, this third stanza never reaches above A. Meanwhile, the expected closing lines are missing. Burton's approach to the song sermon is decidedly different. He regularizes its structure, singing all five verses to the basic melody found in Hayes's stanza one. In doing so, Burton is preserving the power of large-scale repetition, if at the expense of Hayes's more varied narrative form. Even with their respective differences in stanza three, Burton's recording extends the lineage of Hayes's score.

Hayes's and Burton's versions have a single salient pitch difference. Hayes makes ample use of the raised fourth scale-degree: G-sharp in his implied D minor mode. As seen in Figure 2, the pitch is handled carefully and dramatically across the whole of the work, mainly as a chromatic lower neighbor to A-natural. Hayes invokes the signature sound of the G-sharp at every instance of the titular word “mumberlin’,” as seen in mm. 6, 13, 26, 33, 60, 67, 80, and 87. In addition, Hayes makes use of this chromatic pitch during his altered stanza three. He sets the “in” of “in de side” by falling to G-sharp, a dramatic thwarting of the pattern set up by the first two verses, where the analogous moment triggers a rise to C-sharp. This unexpected descent to G-sharp is part of this stanza's uniqueness within Hayes's overall form.

Burton, on the other hand, avoids the raised fourth scale-degree entirely. In his version, every iteration of the three-syllable word “mumberlin’” is sung to the pitches B–A–B, rather than Hayes's B–A–G-sharp. Revising Hayes's raised fourth-scale-degree out of existence, Burton enacts a significant change to the piece, altering its essential modality and silencing one of its signature tones. Burton was also reading Fischer's 1926 arrangement for voice and piano, and it is in Fischer's version that one finds a clue to Burton's alteration.Footnote 52 Fischer, a student of Dvořák at the National Conservatory of Music, refashioned the song toward the Western European lieder tradition: his piano introduction owes a large debt to Schubert's “Am Meer” from Schwanengesang. Burton's version seems to draw almost entirely on Hayes's arrangement. However, one detail from Fischer's score seems to have made an impression: Fischer's setting avoids the raised fourth scale-degree present in Hayes, and Burton follows suit. Example 1 provides a comparison of the titular line from the arrangements by Fischer (1926), Hayes (1948), and Burton (2015). To facilitate the comparison, the example places all three excerpts in the same key and makes their notated rhythms proportional: Fischer's eighth notes are doubled to create a logical visual analogy with Hayes's quarter notes. Burton's line reveals a cross-pollination of influences: his version fuses Fischer's melodic shape on “mumberlin’” with Hayes's syncopated anticipation on “word.”

Example 1. Comparative transcription of Fisher's, Hayes's, and Burton's respective versions of the end of stanza one, line two, revealing Burton's fusion of Fisher's melodic shape on “mumberlin’” with Hayes's syncopation on “word.” To facilitate comparison, all three versions are placed in the same key and Fisher's durations have been doubled.

I have discussed Burton's lyrics at some length without making explicit reference to their religious or liturgical content. In doing so, I am taking cues from Burton himself, via his own stated sense of the songs’ plurality of interpretations and via the visual vocabulary of his album. Regarding the former, Burton makes a rather stirring case for his singing of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” as less related to biblical narratives than to the multiplicity of Black American experiences:

So for me the idea of inhabiting any song is about the connection between all of the people who have gone into that song. That is to say nothing of the subject of the song, certainly, itself. And I don't necessarily mean Jesus in this form, but really the plight of Black America, which is so inherent in this kind of music because it's a universally held emotion that has been placed onto a kind of music onto which you were imported. This sort of music was forced into your life and so you have this universal experience of deep, deep tragedy and deep longing for home and belonging. To place that onto other people's music, you kind of get this other universe that comes through the wholly unique phenomenon that is Black American music: to take the music of your captors and magnify it and multiply it beyond anything that it could have been before.Footnote 53

Burton's positioning of his version of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” in the realm of the “universal experience” recalls Wyatt Tee Walker's observation that certain Spirituals exhibit an “Eternality of Message,” writing that “the message speaks not only to the Black condition out of which it was born but also the human condition at many points, giving a quality of universality.”Footnote 54

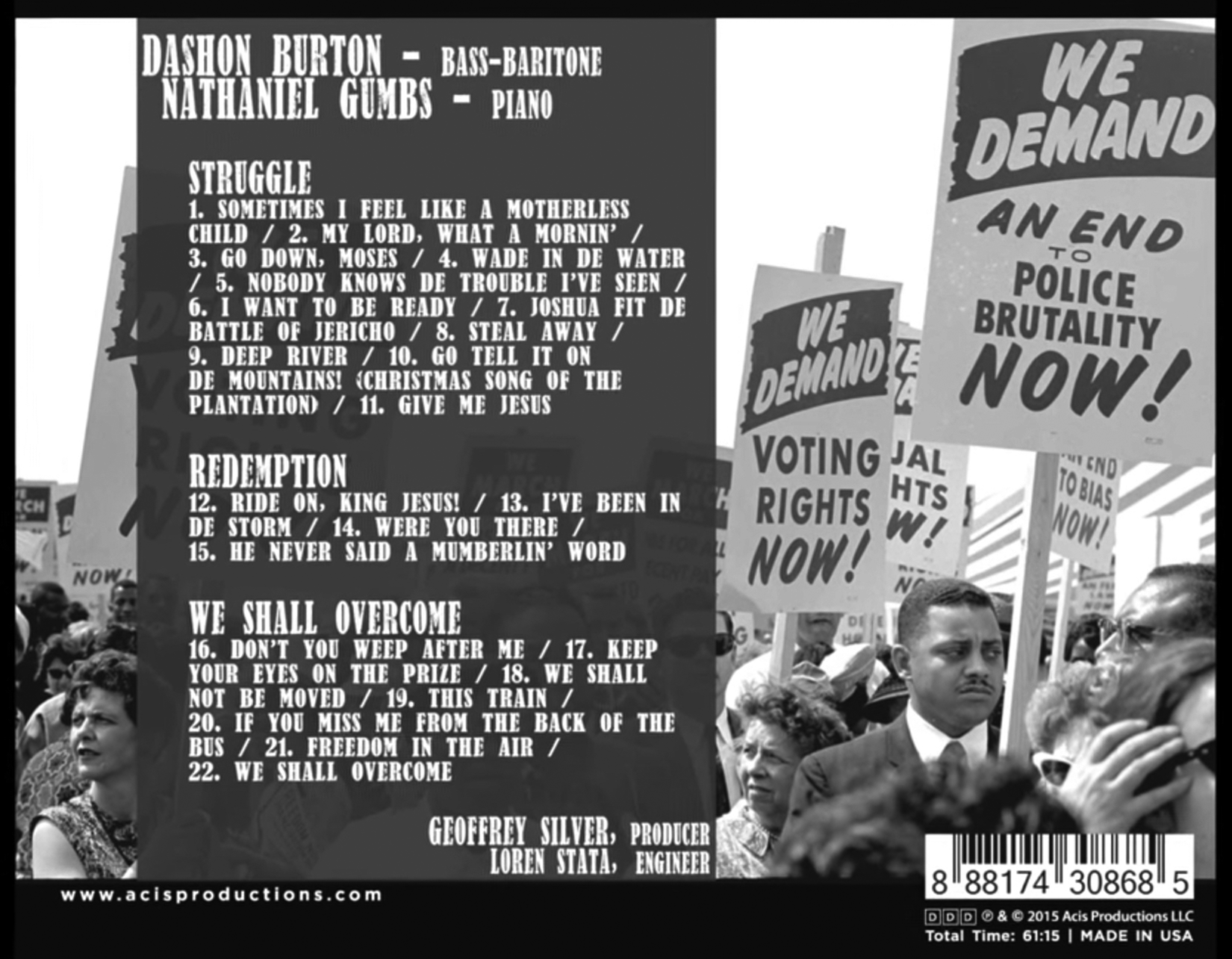

Regarding the artwork that appears in Burton's Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome, none of the images on the compact disc sleeve are religious in nature; instead, the photographs that illustrate the recording are presented in solidarity with the ongoing movement for Black civil rights. Figure 3 presents the back cover of the disc, which features Marion S. Trikosko's August 28, 1963 photograph of proud activists marching for social justice. The most foregrounded placard reads: “We demand an end to police brutality now!”Footnote 55 The two photographs used on the interior of the album sleeve—James K. Atherton's “Emancipator looks down on demonstrators,” taken at the Lincoln Memorial on the same date as Trikosko's photograph, and Leonard Freed's undated “Girl on an M. K. & O. Bus”—document pivotal moments in the history of anti-racist protests in the United States. Burton's chosen iconography contrasts the emphatically liturgical character of Hayes's 1948 collection. This is not to say that Hayes was less interested in civil rights, nor that Burton is less aware of the song's religious content, only that each artist situates “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” in his own way.

Figure 3. Back cover of Dashon Burton, Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome, Acis APL08685, 2015, CD, incorporating a August 28, 1963 photograph by Marion S. Trikosko.

Burton's Recording: Duration, Transcription, and Breath Patterns

As Burton sings a nearly identical melody across all five stanzas, the narrative drama of his version is primarily rhythmic and durational. Melodically, Burton's rendition has no single climactic highpoint: the uppermost note of the melody is heard repeatedly and regularly in the first and third lines of each stanza. The drama therefore occurs not in some long-term ascent to a heroic climax, but in the rhythmic proportions and tempo of his delivery. Rhythmically, Burton presents fluctuating durations within and between each individual line. Befitting Hayes's characterization of this work as a song sermon, Burton's rhythmic fluidity renders any attempt to locate stable tempi neither useful nor possible.Footnote 56 In place of pulsing metric regularity, Burton's singing presents narrative irregularity. Taking the stanza as the largest structural unit, Example 2 illustrates the comparative length of each verse. The duration of each stanza is represented by the size of its square and also noted numerically, in milliseconds, within that square. Burton's control of the pacing creates a natural curve. The narration accelerates from stanza one (“feeling”) through stanza two (“nailing”), finding its apex in the relatively brief stanza three (“piercing”). From there, a deceleration begins in stanza four (“bleeding”) and finds a final calm in stanza five (“bowing/dying”), the longest stanza of all. Burton's pacing tells the story: the most violent verb—“piercing”—is associated with the fastest delivery of the melody in stanza three, while the most expansive declaration—“died”—is saved for the final stanza's implication of eternity.

Example 2. Comparative durations (in milliseconds) of the five stanzas in Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.” This and subsequent musical examples are based on the recording Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome, Acis APL08685, 2015, CD.

Moving from stanzas to individual lines, Example 3 presents a specialized transcription of the lyrics, pitches, and breath sounds across the entirety of Burton's recording.Footnote 57 The melodies of each stanza are nearly identical, and allow Burton's song sermon to gain narrative and dramatic momentum atop a repeating melodic structure. Each breath sound is notated—using the customary breath-mark apostrophe—and numbered. Burton takes thirty-five audible inhalations during the track. Some are more audible than others, to be sure, but each one can be identified by ear. Admittedly unorthodox within music studies, the act of counting breaths both respects and celebrates Burton's sounds as they are. I have no interest in raising the expressive level of these thirty-five inhalations above those of his sung melodies; however, I am also not content to ignore them. They are part of his recording, and deserve to be counted. The melody-plus-breaths transcription of Example 3 reveals the pattern of Burton's breathing across all five stanzas. The regularity of his melodic structure is joined by an exacting and decidedly regular breath pattern. Burton takes seven audible inhales within each stanza, one before each of the first four lines, and one before each of the three cadential iterations: “[breath] O not a word, [breath] not a word, [breath] not a word.”

Example 3. Transcription of the pitches, lyrics, and the thirty-five audible inhales in Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word”.

The inhales that inaugurate each stanza—breaths 1, 8, 15, 22, and 29—track the narrative arc of the lyric. Burton sounds each of them with the character of a great storyteller. All five inhales foreshadow the content of the verse that Burton is about to sing, and together they form a narrative of intensity that supports the lyric. Such breaths are not merely ways for the singer to gain the air necessary to produce sound, but (recalling and repurposing Dunsby) they create a “corporeality in which breathing is heard only when assimilated in the poetic diction.” Example 4 charts the duration of each pre-stanza breath. The first four verses record an intensification of violence: feeling, nailing, piercing, and bleeding. Across the first four stanzas, Burton's pre-stanza breaths become more rapid, moving from 1320 ms, to 978 ms, to 712 ms, to 305 ms. The breath preceding the fourth stanza is less than one quarter of the length of the breath preceding the first. The final stanza breaks this pattern and, in its description of the moment of death, shifts the narration away from violence and towards its ramifications. The duration of Burton's breath leading into stanza five is 1508 ms, nearly five times longer than the breath that ushered in stanza four. This inhale—breath 29—is unlike any other on the recording. It sets a narrative seal on the performance, and can be understood as the dramatic denouement of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.”

Example 4. Duration (in milliseconds) of Burton's audible breaths preceding each stanza of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.”

Studying Burton's narrative rhythm allows us to perceive the enormous rhythmic flexibility that he brings to this work. Examples 5 and 6 present, respectively, the duration of every sounding event in the song sermon's two most contrasting stanzas: stanza three (“They pierced Him in the side”) and stanza five (“He bowed His head and died”). The notation in these diagrams is designed to illustrate Burton's sung rhythm without the rhythmic approximations imposed by standard Western music notation.Footnote 58 This is not an analysis of Burton's singing, but simply a specialized transcription that illustrates the granular detail of his sung rhythm. The notation is rather simple: a standard five-line staff presents all the sounding events, and above each event is a square. The duration of each event is denoted both by the number in the square (in milliseconds) and by the dimensions of the square itself. Scanning the height of the squares provides a comparison of the rhythm of each breath and sung syllable. For example, Burton's first three syllables in stanza three—the three G-naturals on “They pierced Him”—have respective durations of 778, 786, and 380 ms. Those who wish to translate these millisecond measurements faithfully into standard music notation will quickly find that it is difficult, and the task might demonstrate how blunt of an instrument standard Western notation is in the domain of representing performed rhythm.Footnote 59

Example 5. A representation of the precise sung rhythm in stanza three of Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.” The durations are expressed both numerically (in milliseconds) and by the relative size of each square.

Example 6. A representation of the precise sung rhythm in stanza five of Burton's recording of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word.” The durations are expressed both numerically (in milliseconds) and by the relative size of each square.

Comparing Examples 5 and 6 reveals the extraordinary rhythmic contrast in Burton's presentation of the third and fifth stanzas. The pacing of the seven audible breaths he takes during each stanza—denoted by darkened squares—work in concert with the narrative content of the lyric. The moment of highest violence (the “piercing” of stanza three) is met by Burton's quicker, more restless breathing. The duration of the seven breaths in stanza three are, respectively, 715, 267, 416, 321, 227, 551, and 333 ms. Conversely, in the death scene of stanza five, each breath is far longer: they are, respectively, 1538, 1150, 945, 1279, 579, 1082, and 710 ms. Cumulatively, the audible breath sounds in stanza five are more than one-and-a-half times longer than in stanza three. Burton's languorous, knowing breaths in the final verse not only aid the narrative of the lyric, but co-express the dramatic content in the manner of a great oration. Even as they share nearly identical melodic material, the durations of the pitches and the duration of the breaths between these two stanzas differentiate the quick-paced drama of “piercing” from the expansive nobility of “bowing/dying.” Failing to acknowledge the audible and psychological presence of Burton's breath is to miss a significant portion of his utterance.

Narrative Liveness: Ujjayi and the Solemnizing Breath

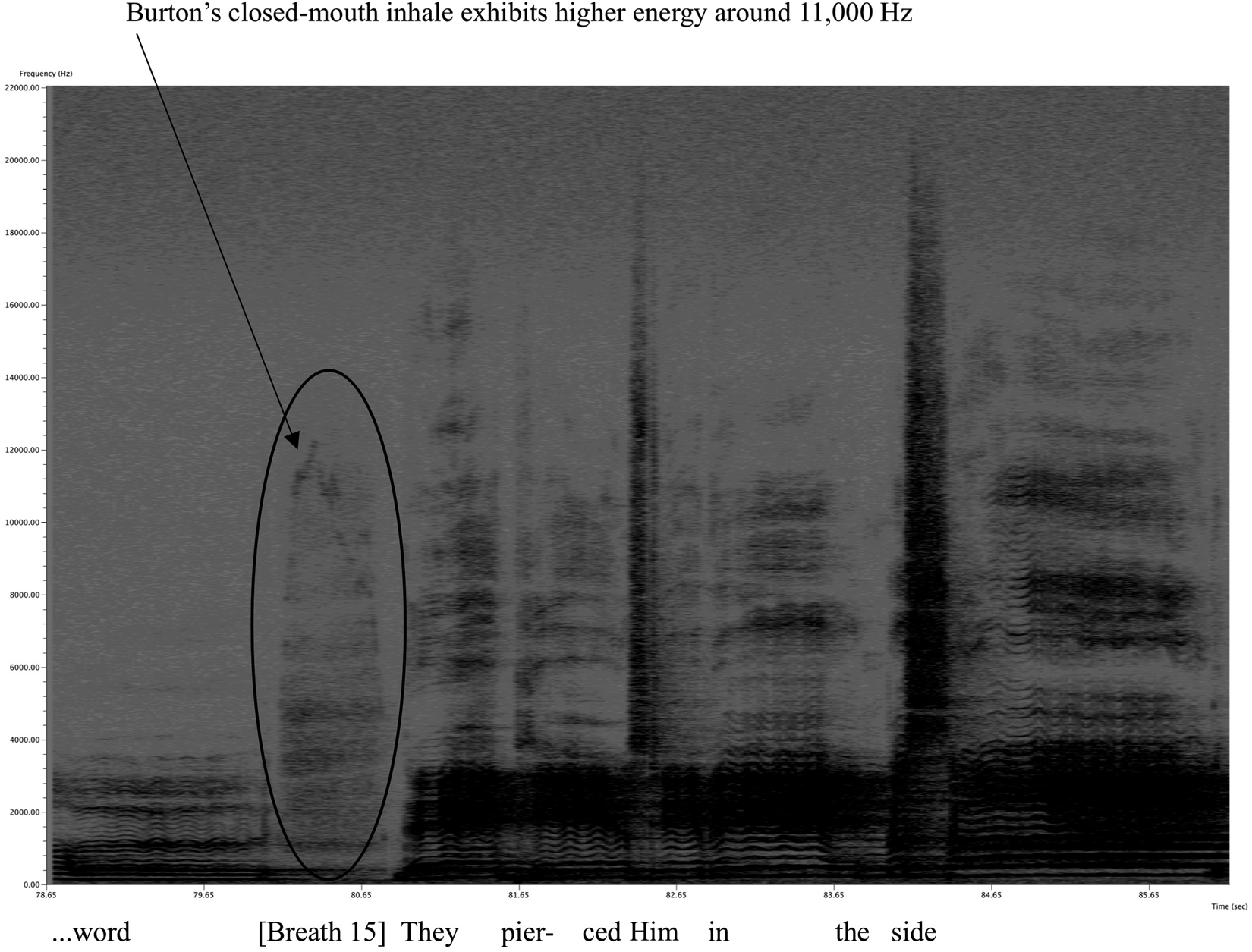

Having moved from stanzas to phrases to syllables, we now arrive at the most subtle level of Burton's interpretation: two single, narrative, audible inhales—breath 15 and breath 29—which exemplify the recording's corporeal liveness. Narrative foils of one another, these two micro-expressions are amongst the loudest and most dramatic inhales on the track. In their own way, each embeds itself in the poetic diction and narrative unfolding. I will call breath 15, which immediately precedes the violence of stanza three, the ujjayi breath, and breath 29, which precedes the final stanza, the solemnizing breath. Both moments are the expressive highpoints not only of Burton's breathing sounds, but of his recording as a whole. These two breaths—like two different chords in a piece of piano music—have functional differences related to their spectral content. Likewise, each inaugurates a contrasting aspect of Burton's narrative pacing: the first initiates a rapid acceleration, the second signals the death scene.

Breath 15 is the loudest and most sonically complex on the track. Occurring at 1:20 and inaugurating stanza 3 (“They pierced Him in the side”), it represents a continued escalation of violence and forms the centerpiece of the feeling–nailing–piercing–bleeding–bowing/dying trajectory. Example 7 displays this breath's spectrographic trace, showing time (in seconds, on the x-axis) and frequency (in hertz, on the y-axis).Footnote 60 For those unaccustomed to reading spectrograms, lyrics are provided for orientation. Unlike all other breaths on the track, breath 15 exhibits high harmonic energy in its upper register. This can be seen in the darker, curving line around 11,000 Hz, marked by an arrow in Example 7. Burton's breath here is quicker than any of the other pre-stanza breaths, and a single listen reveals its signature feature: the glottis in breath 15 is tightened as Burton takes this breath through his nose. The resulting sound is related to the ujjayi breath from Taoist and yoga practices.Footnote 61 Colloquially called “the ocean breath,” the ujjayi is an inhalation taken through the nose whose distinctive sound results from the narrowing of the glottis. Recalling Bain's description of Rashida Bumbray, Burton's fifteenth breath makes audible the “heavy emotional toll required to perform” a work with such violent content. Likewise, following Dunsby, this breath makes us squirm, renders us objective, and connects us more deeply to the singer as narrator. This breath contains the shock and unease portrayed in the subsequent lyric: “They pierced Him in the side.” Listening to breath 15, we not only anticipate the pain of what Burton is about to sing, but, with its vibrant harmonic spectrum, the breath itself reveals an anguish all its own.

Example 7. An annotated spectrogram of 1:18–1:23 of Burton's recording, highlighting breath 15 (the ujjayi breath) in the oval.

Breath 29 is the dramatic foil to the rich spectral fingerprint and quick pacing of breath 15. Occurring at 2:31 and inaugurating the last stanza (“He bowed His head and died”), breath 29 acts as a narrative highpoint in the recording. Example 8 provides a spectrographic picture of this breath in context. Burton's inhale sets a seal over the entire song sermon; it is a knowing, solemnizing breath.Footnote 62 The act of solemnizing confers dignity.Footnote 63 It marks an earnest sobriety—a kind of wise awareness—and a sublime, awe-inspiring nobility. This lengthy inhalation becomes a signal narrative event in the recording. Unlike the effortful breath 15, breath 29 turns the narrative away from the violent world of the killers and towards the intimate, interior death scene of the dying man. Though not loud, breath 29 is vividly audible and when it is acknowledged as an integral part of the music—when it is counted—it acts as a pivotal moment of audition and understanding.

Example 8. An annotated spectrogram of 2:29–2:41 of Burton's recording, highlighting breath 29 (the solemnizing breath) in the oval.

The hyper-expressive quality of breath 29 is enhanced by the fact that Burton inhales, and then audibly stops inhaling, before singing his next note. The hesitation creates a small but meaningful gap between the breath and the “He” that opens stanza five. Burton's temporary cessation of breath is suspenseful, and is marked by subtle, intimate mouth sounds that are denoted in Example 8 with arrows. These small but expressive sounds provide traces of the corporeality that Barthes singles out in his paean to cinematic sound. Indeed, this is a cinematic moment in Burton's recording. The narrative impact of this sound is immense: if the recording were stopped after breath 29, the listener would still have the sense of the content of the final stanza. In the small interstitial moment between the completion of this breath and the beginning of stanza five, even a first-time listener knows that Burton's song sermon—which owes a debt to Hayes's—has reached its denouement.

Although both breath 15 and breath 29 can be classified physiologically as inhales, their spectral content sets them apart as entirely different sound objects. Comparing the respective ovals in Examples 7 and 8, the rapid air flow and narrowed glottis of breath 15 generates sonic activity as high as 11,000 Hz, whereas the slower air flow and more relaxed glottis of breath 29 generates activity only up to 5,000 Hz. The intense inhale that marks the impending violence of breath 15 (“They pierced Him in the side”) is just that: pure air sound. On the contrary, the solemnizing breath 29 (“He bowed His head and died”) is infused with the delicate sounds of Burton's mouth, specifically his tongue releasing from the teeth and his lips parting. This is the very materiality and sensuality that Barthes invokes when he lauds the grain of the voice in recorded audio: as it “granulates” and “crackles,” Burton's voice is “fresh, supple, lubricated, delicately granular and vibrant.” Recognizing the narrative totality of Burton's recording—from his sung melodies to his interstitial breaths and subtle mouth sounds—engenders a connection between singer and orator. It builds a historical continuity between Burton and his antecedents, and calls to mind Hayes's depiction of “the mastersinger types, the original creator[s] of the song sermon” who use a “sonorous simplicity of utterance to stir the imagination.”Footnote 64

Epilogue: Recognizing Sounds as They Are

The presence of microphones at one end, and earbuds or speakers at the other, establishes audio recordings as unique collaborations between composers, publishers, performers, sound engineers, software designers, equipment manufacturers, recording companies, and listeners. I see no reason to consciously and actively hear past the aural evidence of Burton's breath and body, in the same way that it makes little sense to ignore the facial micro-expressions of an interlocutor as they speak. Such information is expressive, and should be recognized and documented alongside all sounding events. Such attentiveness generates a mode of listening that reckons with a complete, equalizing census of all the sounds present on a given recording. Evidence of corporeal liveness captured on recordings provides a vivid window into the humanity of music-making. Often, such sounds remain on recorded tracks simply because their placement within the soundscape makes them too difficult for audio engineers to remove. As shown in the preceding analyses, Burton's inhales are integral to our interpretation of his interpretation.

Millisecond-level transcriptions and audio spectrograms have their limits. Numbering, as an act, can be seen to blunt the expressivity of both art and life. Writing about the imposition of house numbers on the fluid landscape of city streets in the United States, Dierdre Mask writes: “Numbering is essentially dehumanizing. In the early days of house numbering, many felt their new house numbers denied them an essential dignity.”Footnote 65 Microtiming Burton's rhythm might seem to support Mask's point, as this type of transcription superimposes numbers onto the human experiences of both singing and listening. However, I enact this hyper-vigilant study of Burton's recording not to suppress its dignity, but to emphasize and amplify it. Spectrographic documentation is a refined approach to transcription that pays attention to all sound events, not simply the lyrics and melody of Burton's version, but the rhythmic timings and breath sounds that create its unique audio fingerprint. Burton's audible breaths—here celebrated through close-listening, measurement, and naming—are generative and suggestive of a corporeal liveness that builds a historical continuity between Burton, Hayes, Fischer, Work, Johnson, and the original composer(s) of the song sermon.

Analyzing Burton's performance of “He Never Said a Mumberlin’ Word” in such detail does not quantify all of its embedded resonances, nor does it exhaust its capacity for meaning. Indeed, Roland Hayes himself might feel that this study misses the point, given his characterization of academic music studies:

That specific stamp of unforgettable dignity that gives life and reason to an individual or to a piece of music is often difficult to analyze … It is curious how in our times such religious poetic creations as the Hebrew chant, Palestrina, Lassus, Gregorian chant, the great masses of Bach, Beethoven, the monumental Biblical oratories, the religious folk songs of my people, have become concert fare, and sometimes museum pieces, that we study with the rational abstract aloofness of the scholar or student.Footnote 66

The quantification and micro-temporal measurement of Burton's singing does not spoil the spiritual or emotional effect of the listening experience; instead, the rationality and abstractness of analytical scholarly work is itself a form of love and respect for the material and the artists being studied. Jennifer Bain devotes scholarly energy to Rashida Bumbray, Jennifer Iverson to Björk, Jonathan Dunsby to Charles Panzéra; such research emerges, in part, from admiration for specific recordings. My study of this seminal piece of American music is no different. Documenting Dashon Burton's every sound and breath cultivates a sensitivity to the location, contour, and duration of each element of his music-making, and celebrates the “specific stamp of unforgettable dignity” present in this recording.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the JSAM editors Emily Abrams Ansari and David Garcia, to the journal's anonymous reviewers, and to Dashon Burton, Sam Burton, William Cheng, Lea Douville, Celia Douville Beaudoin, Allie Martin, Olivier Senn, Shahzore Shah, Geoffrey Silver, and Loren Stata.