Introduction

The aim of this article is to demonstrate that the core fabric and elements of the decoration of the funerary structure of ‘Abd al-Samad in NatanzFootnote 1 pre-date the early fourteenth century, with some elements probably dating back to the Seljuq period (431-590/1040-1194), or slightly later, and to refine the chronology which saw the structure repurposed and redecorated. A new ceiling and extensive lustre tiles were modifications added to the pre-existing structure of the shrine of the Suhrawardi Sheikh Nur al-Din ‘Abd al-Samad and were sponsored by the Ilkhanid amir Zayn al-Din al-Mastari in a series of separate consecutive interventions in the early years of the fourteenth century. Particular attention is dedicated to the characteristics of the original architectural revetments of the Shaykh's shrine, revealed beneath the mortar which held the, now removed, Ilkhanid lustre tile revetments in place.Footnote 2

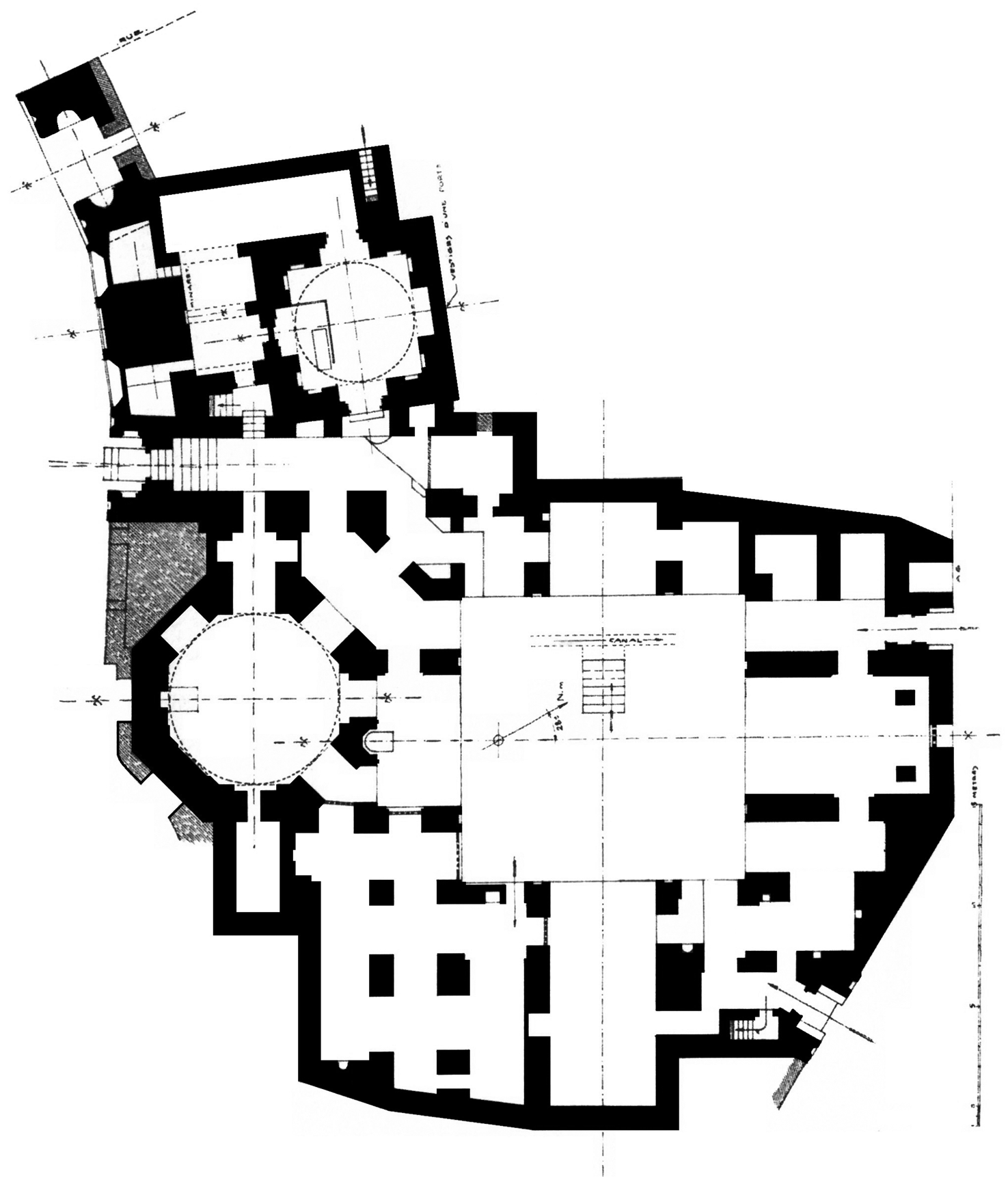

The complex reached its most complete form under the Ilkhanids, and consisted of four main structures, namely; the mosque, incorporating the earlier octagonal domed structure, the shrine of ‘Abd al-Samad, the minaret, and the khanqah with a monumental pishtaq entrance portal (Figures 1 and 2). Each of these structures was built in different phases and modified over time, by a number of different patrons. While the complex is understood as an Ilkhanid masterpiece of architecture and decoration, its earlier phases, with the exception of the octagonal domed structure,Footnote 3 are often only mentioned in passing, while later phases tend to be seen as renovations. However, these ongoing interventions attest to the significance of the monument, and show constant patronage of the site from the tenth century all the way through to the Qajar period and beyond.

Fig. 1. Pre-restoration image of the shrine of ‘Abd al-Samad in Natanz viewed from the south, taken by André Godard before 1936.

Fig. 2. Plan of the Natanz Complex.Footnote 17

The ‘Abd al-Samad complex is located in the historical centre of the settlement of Natanz,Footnote 4 which is located between Isfahan and Kashan in central Iran. The complex consists of a series of interconnected structures which have been altered, extended, rebuilt and restored numerous times over the course of the last millennium. Although several articles and one monograph have been published about the monument, from the 1930s onwards,Footnote 5 significant elements of the constructive and decorative sequence of the complex remain unclear. The accepted chronology, most coherently elucidated in a number of publications by Sheila Blair,Footnote 6 gives a date of 389/998-99 for the construction of the domed octagonal structure, now incorporated into a larger four-iwan plan congregational mosque, with the square shrine of the Shaykh added in around 707/1307-08, the portal and (no longer extant) khanqah added in 706/1306-07,Footnote 7 and the minaret between the shrine and the khanqah built shortly afterwards in 725/1324-25, by Shams al-Din.Footnote 8

Natanz is located on the ancient trade and pilgrimage routes between Isfahan to the south and Kashan and Qum to the north, and is mentioned in Mustawfi's Nuzhat-al-Qulūb.Footnote 9 Several of the monuments in Natanz testify to its past, with the fire temple located near the complex in question being the oldest known structure, and indicating occupation of the settlement in Zoroastrian times.Footnote 10 Later structures, including the Kuche Mir mosque as well as the Complex of ‘Abd al-Samad, testify to the significance and expansion of the settlement under the Buyids, Seljuqs and Ilkhans. The town acquired specific importance during the Safavid period, especially under Shah ‘Abbas I, who often travelled to his estates in Kashan, passing Natanz on the way. This resulted in the construction of Safavid monuments in and around Natanz,Footnote 11 as well as a renewed interest in the complex of ‘Abd al-Samad itself. Further significance of the complex is also evident from the numerous Safavid restorations and modifications to the ‘Abd al-Samad complex.Footnote 12 These modifications comprised, above all, minor repairs to the structure and application of architectural revetments on its surfaces. The domed area of the octagonal structure incorporated into the Friday mosque was redecorated with wall paintings. Additional wall paintings and stone slabs with historic inscriptions concerning modifications were placed on architectural surfaces within the mosque. Furthermore, tile revetments were added to the base of the minaret of the complex and the shrine of the Shaykh was redecorated. Whitewashing of the Shaykh's shrine and the mutilation of the avian elements of the lustre tiles also seems to have been executed in this period.Footnote 13 The monument has a long and complex history, and over time its function changed from first one, then two, simple domed tomb structures into an extensive pilgrimage complex, located on one of the main routes to the holy city of Qum.

The construction phases of the monument have been elucidated by Blair, based on the existence of several dated historic inscriptions.Footnote 14 However, additional sources of evidence regarding further constructive and decorative interventions in the shrine remain in situ, and so far have only received very scant scholarly attention. The oldest structure of the complex is the domed octagonal structure, with an historic inscription in fired brick and stucco giving the year 389/998-99, located around the base of the dome. The inscription was discovered during the restoration programme that took place between 1970 and 1978.Footnote 15 The octagonal structure appears to have been incorporated into a larger mosque during the Seljuq period, of which no traces remain, and it was later rebuilt into a four-iwan type Ilkhanid mosque.Footnote 16 Historic inscriptions on the monument suggest that the mosque of the Ilkhanid period was constructed between 704/1304 and 707/1307-08, and that this was an intervention of mosque re-building. The most problematic area of the complex with regards to dating is the shrine of the Shaykh. This is currently assumed to have been built in a single phase in 707/1307-08, based on the date in the stucco inscription, which runs along the base of the muqarnas dome of the shrine. However, a closer look at the shrine structure and the remains of its revetments illustrates that the shrine was constructed and decorated in several stages and that structurally it largely predates the year 707/1307-08.

The Shrine of ‘Abd al-Samad: its features and their chronology

The ground floor plan of the funerary structure is cruciform and it consists of a square room which originally had an entrance on each side, with eight shallow blind recessed arches, one either side of each of the four central openings. The one on the southern side was closed off at the time of the installation of the mihrab, and the building is topped by one of the finest surviving muqarnas domes.Footnote 18 The most remarkable aspects of the interior were the revetments, which were applied in several stages and comprise carved rising joint plugs set between fired bricks in the walls, carved gracile engaged stucco columns, lustre tiles, which are dispersed in different museum collections, and the monumental stucco inscription band, which runs along the top edges of the supporting walls. Close study of the shrine reveals pieces of evidence that show that its construction consisted of several phases, rather than there having been a single intervention in 707/1307-08.

The two important landmarks for understanding the nature of the patronage and chronological development of the shrine are the death of the Shaykh, and the death of the main Ilkhanid patron of the complex. The Shaykh passed away in 699/1299-1300,Footnote 19 and it would be logical for the construction of his shrine to have begun immediately after his death, as in the case of the Pir-i Bakran mausoleum, where the exact date of Pir-i Bakran's death is mentioned in historic inscriptions, and the same date is found in several parts of the mausoleum.Footnote 20 It is therefore probable that at least some of the interventions on the Natanz site took place before 707/1307-08. Moreover, the inscriptions in the mosque of the Natanz complex mention repairs and refurbishments, in place of construction ex-nuovo, suggesting the existence of an earlier structure on the site, which would make the existence of an earlier shrine on the site more plausible.Footnote 21 The second important date is the year 711/1312, when ‘Ali al-Mastari was executed. The death of the patron signalled a break in continuous patronage of the complex, with the 37-metre-high minaret being the result of a slightly later construction phase under Shams-al Din Muhammad.

Additional evidence for the pre-Ilkhanid, and probably Seljuq-era, dating for the beginning of the construction of the shrine structure can be found at the nearby Kuche Mir mosque, which comprises both Seljuq and Ilkhanid phases of development. This mosque was enlarged and decorated with an exquisite stucco mihrab during the Ilkhanid period (probably contemporary to the ‘Abd al-Samad shrine), but the main structural core of the mosque dates to the Seljuq period.Footnote 22 It is also probable that the main core of the ‘Abd al-Samad complex was already constructed in the Seljuq period, when the domed octagonal structure was made part of a Seljuq congregational mosque. Given the qibla variation, it is likely that the mosque was built earlier in the Seljuq period, and the original iteration of the shrine was built somewhat later, following an advance in the calculation of the direction of Mecca. In the Ilkhanid period, the entire complex was rebuilt, enlarged, and refurbished,Footnote 23 with the addition of the khanqah, and the minaret after the death of al-Mastari. Such a pattern would not be unusual, as several other tombs and pilgrimage complexes in the wider region all underwent numerous refurbishments and continuous patronage for the purpose of pilgrimage over the longue durée.Footnote 24 Moreover, it was not only shrines that received ongoing patronage through different historical periods, as the same pattern can be seen at a number of congregational mosques. Studies of several monuments which have been known as Seljuq or Ilkhanid have revealed that the majority of them were founded at an early stage, and were then modified through time by different patrons.Footnote 25

The original structure was almost certainly built as a funerary monument, but the closing off of one entrance, and the installation of the lustre mihrab and tiled dado, signalled a transformation of the shrine chamber into a prayer space for pilgrims, notwithstanding the proximity of the nearby mosque. This is very similar to the parallel case of the Pir-i Bakran mausoleum, where a stucco mihrab was installed to close off the funerary iwan and therefore to transform the funerary iwan into a pilgrimage structure consisting of the burial chamber with the tomb of the Shaykh and the adjacent prayer space. Both examples, at Natanz and Pir-i Bakran, exemplify the change of a simple tomb into a true pilgrimage site. This is in line with the fostering of pilgrimage activities by Ghazan Khan (d. 703/1304) after his conversion to Islam, as well as later during the time of Öljeitü (d. 716/1316).Footnote 26

In her monograph on the complex, Sheila Blair dismisses the possibility of the shrine having been built prior to 707/1307-08, based in part on the lack of any mention of other figures associated with the site in the sources.Footnote 27 While it is in theory possible that the interior decoration was executed in an anachronistic monochrome manner, and rapidly covered over with mortar and tiles,Footnote 28 the construction break around the mihrab (Fig. 3) and the variance in qibla alignment from the Ilkhanid mosque (Fig. 2) are more problematic. If the entire shrine complex, with the exception of the earlier Buyid octagonal domed structure, was the result of a single campaign by Zayn al-Din al-Mastari in the first decade of the fourteenth century,Footnote 29 then the reason for the construction break at the side of the entrance portal accessing the shrine and the mosque also becomes rather difficult to explain. Furthermore, joints between the stucco revetments and remaining lustre tile adhesion mortar also testify to the fact that the revetments of the shrine structure were applied in a series of consecutive interventions, rather than a single decorative undertaking. The hand-carved decoration incised into the rising mortar joints of both the shrine and the portal have been published by Blair, in which she describes them as stamped plaster end plugs.Footnote 30 Donald Wilber has challenged the early-fourteenth century date for the core of the building based on these visible areas of incised patterns in the rising joints inside the shrine.Footnote 31

Fig. 3. Construction break on the right of the mihrab.

Evidence for the Multiple Phases of Construction and Decoration

There are a number of elements that provide evidence of a much earlier phase of construction than the early-fourteenth century date, to which the whole building has been generally attributed in the literature, based on the date of 707/1307-08 given in the upper stucco inscription band inside the shrine. The internal structural and decorative evidence is analysed chronologically in order to demonstrate more clearly the order in which the different interventions took place. This is followed by an assessment of the somewhat more limited external evidence. This evidence includes the entrance portal between the mosque and the shrine, as well as elements of the octagonal section of the shrine itself. Among the key elements that will be examined in detail are the areas of rising mortar joint decoration on the qibla facing wall of the shrine. These were subsequently covered up by the glazed tile dado and the decorative engaged columns. They were only revealed following the removal of these tiles in the nineteenth century,Footnote 32 along with subsequent restorations, alterations and other interventions. Establishing the nature of the possible phases of construction between the late tenth and early fourteenth centuries is the focus of the following discussion.

There is a clear vertical construction break all around the area from which the mihrab tiles have been removed (Fig. 3). This area features the traditional Seljuq-style X-and-O rising joint decorations in the section around the construction break, but none on the later mihrab section, with the internal surface covered in a smooth fine coat of plaster. There is evidence of a door indicated on Godard's plan (Fig. 2), and an image of the exterior appearance of the wall in his publication of the complex.Footnote 33 This, alongside the construction break around the mihrab, the existing entrance, and the opposite side of the structure only recently having been bricked up, all prove that in its original iteration the building had four openings. This would place it firmly into realm of the chahar taq structures found across the wider Iranian world. Earlier examples include the two Ghurid ones in ChishtFootnote 34 and the tomb of the Samanids in Bukhara.Footnote 35 The no longer extant Imamzada Rabia’ Khatun in Ushturjan, which had a stucco mihrab dated 708/1308 that is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Tehran, appears to have featured a similar ground floor plan.Footnote 36 The later Imamzada Baba Qasim (1340-41) in Isfahan also features a similar ground floor plan.Footnote 37 Such a layout would also have fitted in with the earlier Buyid octagonal tomb right next to it, which was originally a free standing octagonal domed structure with an ambulatory open on all sides, and is considered to be the earliest dated dome structure in Iran.Footnote 38

In addition, attention must be focused on the lack of axial alignment between the shrine structure and the later khanqah façade and the minaret, added during various phases of construction over the course of the first quarter of the fourteenth century. Beyond the shrine itself, there is a shift in alignment and a clear construction break between the minaret and khanqah façade, and the earlier portal to the entrance corridor located between the octagonal domed building and the shrine. This entrance, which is flanked by tall recessed panels with pointed arches, also features slightly different, and more standardised, rising-joint decorations.

Regional Comparanda

Another square plan structure which is open on all sides is the northern domed structure at the Masjid-i Jami‘ in Isfahan, commissioned by Taj al-Mulk in 481/1088-89. In addition, the internal mural decoration of several north-western Iranian monuments of the Seljuq period, such as the Friday mosque of Sujas, the Friday mosque of Qurva and the Pir mausoleum at Takistan,Footnote 39 can be compared with the interior of the square shrine, as well as with elements of the decoration and form of the lower portion of the entrance portal to the octagonal and square structures.

Given the convincing case made by Blair for the octagonal structure having originally been an imamzada for a descendant of the Prophet,Footnote 40 it is not surprising that another tomb would subsequently have been built in close proximity. The questions remain; when was it built? and for whom was it built? Unfortunately, both these questions will in all probability never be definitively answered, as there does not appear to be any information pertaining to this period in the written sources.Footnote 41 The hope of some baraka being gained from the dedicatee of the octagonal tomb may well have influenced the original patron of the square tomb to build it in such close proximity. Despite the well-known Sunni orthodoxy of the Seljuqs, there remained a large Shi‘ite population in the region around Kashan, which only lies a short distance to the north. Over time the tomb became part of a large pilgrimage complex, which appears to have been Shi‘ite from at least the Ilkhanid period onwards.Footnote 42

It is important to note the almost ten-degree change in qibla alignment from the octagonal Buyid tomb and the later square one.Footnote 43 What is more surprising in Natanz is that the later mosque is built on the same alignment as the earlier octagonal domed structure to which it was connected at several points, rather than that of the square-plan shrine. This variance is especially problematic if one were to accept the argument that the mosque and shrine were part of the same phase of construction. Misaligning the qibla of a mosque simply to integrate an earlier octagonal structure, which is awkwardly executed anyway, and then highlighting the misalignment by building the shrine right next to it with a clear variance of nearly ten degrees would be unprecedented and seems highly unlikely.

The Seljuq gateway in the north-eastern corner of the Masjid-i Jami‘ in Isfahan, dated 515/1121-22,Footnote 44 features the same simple X-and-O rising joint decoration incised into the mortar, as well as a very similar style of the more complex variant, located in the two panels just above the capitals in the background of the short inscription on either side of the door. These patterns, alongside the presence of square epigraphic Allah patterns and the same complex variant of joint pattern on the seemingly coeval east iwan of the Masjid-i Jami‘ in Isfahan, indicate that the core of the Natanz shrine may well date from the twelfth century. There are also rectangular epigraphic sections between bricks, at least one of which clearly reads Allah, while another ends with Allah, but features a preceding word, which is too effaced to be certain of the original reading.Footnote 45

A comparable site for understanding the multiple phases of Ilkhanid interventions can be seen at the Imamzada Yahya at Varamin, south-east of Tehran. In this case a shrine, formerly part of a larger complex with a portal and other structures, most of which are now lost,Footnote 46 has evidence of a series of different phases of decoration under the Ilkhanids. A phase in the 660s/1260s saw the application of a tiled dado, with sixty of the tiles bearing dates between 661 and 662/1262 and 1263. Two years later a mihrab, now in Honolulu and dated 663/1265, was added.Footnote 47 There was an additional phase of decoration in the early fourteenth century, which may have included the installation of the lustre tile revetments for the cenotaph of the Shaykh dated 705/1305,Footnote 48 as well as a stucco inscription band which was added above the tile dado shortly afterwards, in 707/1307-08.Footnote 49 This final addition covered part of the earlier brickwork with rising joint decoration, and corresponds with the later addition of an inscription band above the polychrome star and monochrome cross tiled dado at the Natanz shrine. In the latter example the new band was in lustre tiles, but, as discussed above, a similar, if somewhat larger, stucco band was also added at the base of the muqarnas ceiling. The interior at Varamin also features a series of rising joint plugs, including, but not limited to, the X-and-O pattern, and the more complex variant seen in Natanz, as well as tip-to-tip triangles, which have yet to be found at the ‘Abd al-Samad shrine complex. In both cases the later interventions cover parts of the rising joint plug decorated brickwork, and at Varamin significant areas were deliberately left visible. However, this may also have been the case at the Natanz shrine, prior to the application of the kahgil (mud and straw) and plaster layers. The greater epigraphic evidence at the Varamin shrine for a series of separate phases of decoration,Footnote 50 and the covering up of one type with another, is instructive for understanding the somewhat less well documented interventions that took place at Natanz.

Fig. 4. Rising joint mortar decoration beneath the (lost) band of lustre tiles, ‘Abd al-Samad Shrine, Natanz.

Fig. 5. North wall and arch of the ‘Abd al-Samad Shrine, Natanz.

It is clear that the early-fourteenth century additions to the building made a major difference to the internal appearance of the space. However, the vertical recessed panels above the dado height on all four walls are original, as a small section of missing kahgil and whitewash reveals the presence of the same basic X-and-O rising joint pattern as is found on the rest of the walls. Tall recessed panels of the kind seen on both the portal and the inside of the shrine can be seen on the northern dome in the Masjid-i Jami‘ in Isfahan as well as the entrance of the Seljuq mosque in Ardistan.Footnote 51

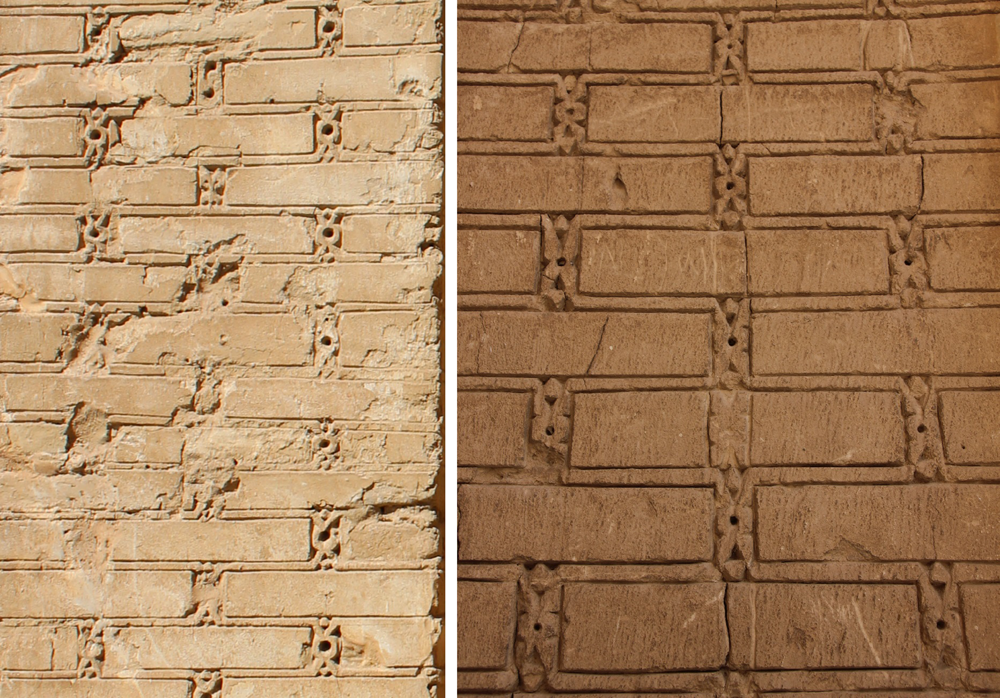

The Seljuq Incised Rising Joint Patterns

The earliest surviving elements of the decorative programme of the building can only now be seen as a result of the removal of the glazed tiles from the dado and around the mihrab in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Large sections of the underlying brick wall feature an array of different incised patterns in the mortar of the rising joints between the bricks. These are typical of Seljuq work, and the following section examines the surviving examples in detail in order to better understand the earliest phase of the shrine's construction and decoration.

A single brick-width return juts out into each side of the four former entrances to the building, with the ones on either side of what was to become the mihrab niche featuring alternating full bricks, and then two half bricks with an incised rising joint X-and-O plug in between them. Large areas of the visible brickwork do not feature any plugs, including the upper area of the wall to the right of the mihrab area, even though they are present at a similar level on the left. It is possible that the original dome and part of the upper walls fell at the same time as part of the dome over the octagonal structure nearby collapsed.Footnote 52 The damaged walls would then have been rebuilt with plain brickwork, upon which the muqarnas ceiling was built, and the rest of the decoration except the lustre epigraphic frieze was applied. The upper exposed plug in the brickwork on the left of the mihrab area, as well as other sections on the edge by the construction break, shows evidence of the original brick surface being covered in a thin layer of white plaster, with paired or single lines incised to mimic the appearance of the mortar beds beneath (Fig. 8), and appears to have been used to fill the rising joint voids into which the X-and-O patterns were then carved.Footnote 53

A section of the mortar that held the Ilkhanid star and cross tiles in place has been removed near the corner to the right of the mihrab recess, revealing a section of the fired bricks laid up to the height of the beginning of the recess.Footnote 54 This lower section has no wide rising joint gaps, and so no rising joint decoration, unlike the section above. This shows that the lower portion of the shrine, separated by a band the height of a single course of bricks, which may have been wood, was plain while the rest of the internal walls were decorated with incised lines and carved rising joint decoration.Footnote 55

The uppermost visible plug is inside the recessed niche to the left of the mihrab recess, proving that the shallow niches are contemporaneous with the first phase of construction, even though the engaged columns and capitals running up the sides are from a later phase of development. The clear construction break running in line with the edge of the recess in the eastern wall, behind the dado tiles to the right of the entrance, adds to the evidence for the recesses being part of the original phase of construction. The engaged column can be seen to extend behind where the lustre tile frieze ran, but not all the way down the side. Instead it sits on a later sill in line with the top of the star and cross dado. It is clear that the recesses were decorated with engaged columns and capitals, of the same form as seen in the cenotaph tiles now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,Footnote 56 presumably at the same time as the larger stucco engaged corner columns and the stucco inscription band were added.

Fig. 6. Corner to the right of the mihrab recess; detail of the original brickwork and later column.

Fig. 7. Construction break beside the blind recess to the right of the mihrab, with the later engaged column extending down behind the (lost) lustre inscription band to the height of the top of the star and cross tile dado.

Fig. 8. Incised construction lines in the earliest phase of brick decoration to the right of the mihrab niche (L), and square Kufic Allah brick plug (R).

On the right of what was to become the mihrab recess there is a partial square epigraphic plug with the last part of Allah (Fig. 8 (R)), but it is in a far more angular and square form of Kufic than the corresponding square plug on the right side, which also features Allah but in a somewhat more cursive script (Fig. 9). This is suggestive of at least two different craftsmen being responsible for the execution of the wall decoration in the initial construction phase of the structure.

On the left side of the mihrab there is also a more complex rising joint plug, the same size as the X-and-O plugs. In the same area the plugs can be seen to extend under the later stucco engaged corner columns. Vertical construction lines for laying out the pattern of the incised plugs are visible on the left side of the mihrab recess, just to the left of the first, presumably Seljuq, phase construction break marking the edge of the original opening. (Fig. 8 (L)).

Fig. 9. Rising joint plugs to the left of the mihrab, including ones extending underneath the stucco corner columns.

In the earliest iteration of the building it would have been a pure white space, owing to the thin coat of plaster over the brickwork into which the lines were incised, with the appearance of vertical lines of rising joint brick plugs on every other course, as well as creating the appearance of diagonal lines, with thin incised lines connecting the plugs horizontally. In addition, there was a greater variation of plugs, including a square one with the name of Allah, in the qibla wall. It is not clear if the walls in the eastern half of the building lacked plugs from the start, or if the building was significantly damaged and major sections of the walls needed to be rebuilt.

The Ilkhanid Dado Tiles

The application of a thick layer of mortar over the lower portion of the brick walls and their attendant incised patterns allowed for the first introduction of colour and glazed decoration to the shrine. Six full bands and one half band of star-and-cross tiles were added to the walls to create a glazed dado, radically transforming the decorative aesthetic of the building.

The length of the engaged columns in the pointed-arch topped recesses in the walls shows that they were added at the same time as the glazed star-and-cross tile dado, with the columns starting at the top of the dado, and the lower portion of the recesses filled in to allow a surface for the mortar to be applied (Fig. 7). These columns in the recessed niches are flush with the original, pre-kahgil covered wall surface. Subsequently, the famous lustre inscription band with the defaced birds was added at a later date. The fact that the main corner columns supporting the upper inscription band also extend to the top of the same dado adds additional credence to this observationFootnote 57 (Fig. 6).

The tiles that were added over the brickwork and rising joint plugs consisted of plain monochrome turquoise glazed pointed-tip cross tiles, several of which remain intact,Footnote 58 and corresponding eight-point star tiles, of which little is known but they were probably lustre star tiles. One small fragment of the bottom point of one half-tile in a corner remains in situ (Fig. 10), which shows that the stone paste tiles were on a white base glaze, with underglaze black and blue decoration, which could have been combined with lustre decoration.Footnote 59

Fig. 10. Fragment of eight-pointed glazed half star tile from the dado wall revetment of the shrine.

The multiple stages of Ilkhanid work have already been referred to by Blair, as the lustre tiles originally thought to be from the cenotaph, some of which are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,Footnote 60 have a partial date that has been read as Shawwal 709, being March 1310.Footnote 61 The stucco band was presumably completed by 707/1307-08, while the lustre frieze is dated Shawwal 707/March 1308, based on the frieze tile in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Footnote 62 The aim here is to push the chronological range back for the underlying structure, based on the stucco plugs and the addition of a mihrab, and also to highlight the surviving evidence in the building. Such observations make it possible to prove the exact sequence of decorative additions, while acknowledging that the absolute dates of some of the stages cannot be determined through visual analysis alone, and that additional dated inscriptions are unlikely to be found.

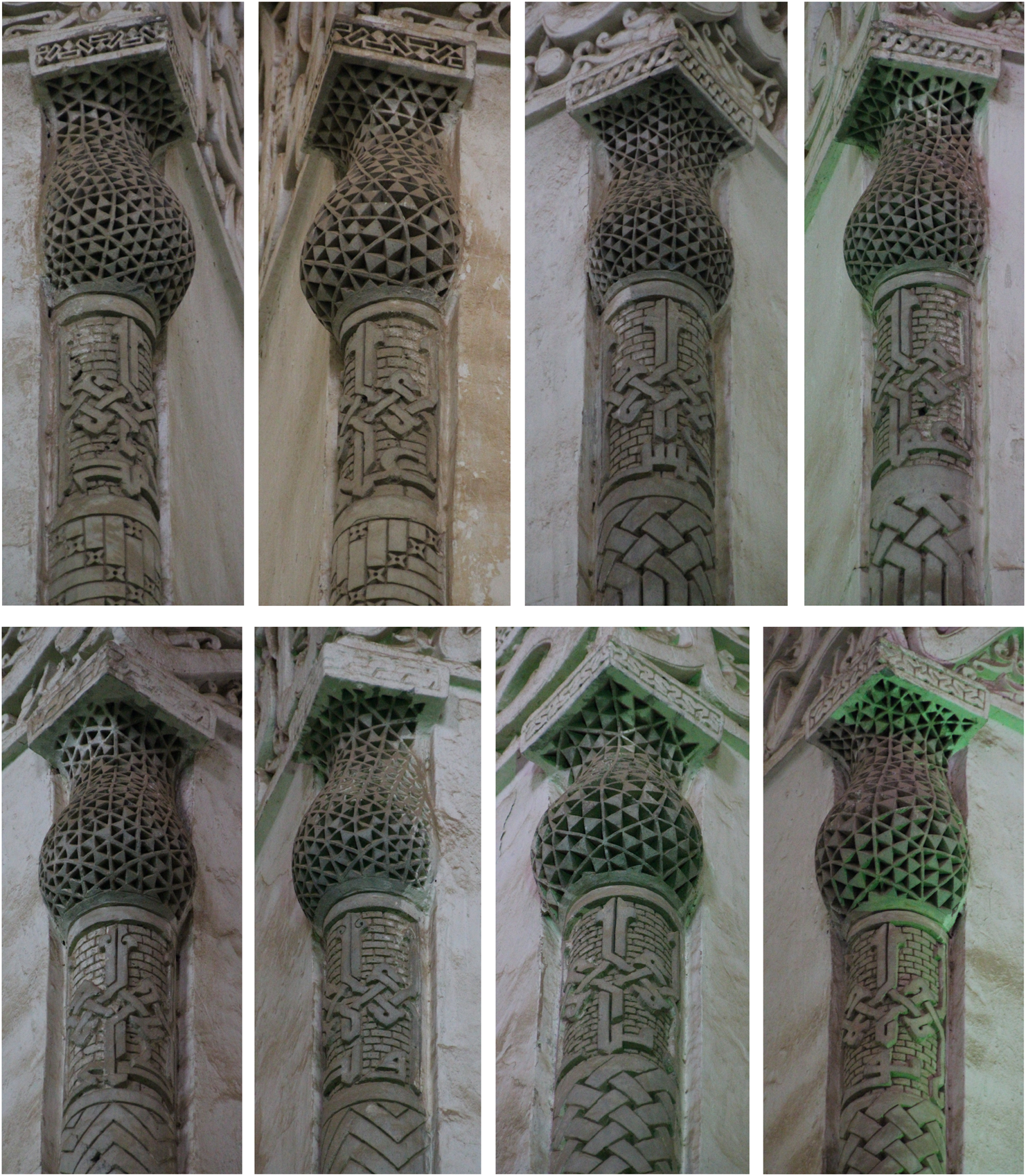

The Stucco Corner Columns

The interior of the shrine features eight engaged stucco columns, two on each wall, with four different patterns. The two on either side of the mihrab niche are identical, featuring a knotwork pattern which is, perhaps, not surprising given the location, the most complex of the four variants (Fig. 11). A chevron pattern is employed on the two columns flanking the arched recess in the northern wall, (Figure 11 (R)) while the two columns flanking the current entrance, from the south, have something akin to a fictive brickwork pattern. This consists of vertical and horizontal rectangles of varying lengths, separated by squares featuring four-point star patterns. In addition, the central vertical axis on the outside edge features a four-petal like pattern in the centre of the lozenge shape created by the diagonally set star motifs (Fig. 11 (R)). The columns cover sections of X-and-O plug decorated areas (Fig. 9), proving that the first stage of decorative brickwork did not include the corner columns. These columns were clearly built to line up with the protruding inscription band above, which is unquestionably from a later construction phase than the initial plastered and incised brickwork with rising joint plugs in the Seljuq manner. It is clear that the carved stucco columns, and the inscription topping them, can be securely dated to the Ilkhanid period, and signal the beginning of Ilkhanid interventions.

Fig. 11. Engaged column details from the east (L), south, (C) and west (R) walls of the shrine.

Fig. 12 shows the base of the column on the right of the eastern opening, with the basket-weave pattern. It is clear that the columns, which are produced out of grey gypsum-based stucco,Footnote 63 needed some of the curvature to be chipped away in order to allow for the corner pieces of the lustre tile frieze to be installed, in the last of the Ilkhanid-period interventions in the decoration of the shrine.

Fig. 12. Base of the column to the right of the mihrab recess.

The dated stucco inscription, which mentions the patron of the shrine as Zayn al-Din al-Mastari, was part of a modification to the original design of the building, and this may well have also included rebuilding parts of the walls and the construction of the muqarnas dome. An argument in favour of this is the fact that the inscription uses the term qubba,Footnote 64 which appears to refer to the dome, rather than to the whole structure. Additional evidence for different phases of construction has already been seen in the way the stucco columns were applied.Footnote 65

Decoration of the Column Capitals

The signature split across the bands below each of the eight capitals is well known, and has been read as the name of the craftsman Hasan Ibn ‘Ali Babawayh. However, detailed images of all the columns were not available when this reading was published,Footnote 66 and there are additional unclear elements at the end of the inscription. It appears to closely resemble the signature of the craftsman who signed the tiles in the Metropolitan Museum of ArtFootnote 67 and the stucco mihrab from Mahallat-i Bala,Footnote 68 and reads:Footnote 69

عمل حسن على احمد بابو [يه ] بنا ويدگلى

Work of Hasan ‘Ali Ahmad Babawayh banna Vidguli

The inscription, which starts atop the column to the right of the mihrab recess, is arranged in a manner that is without parallels. The signature is spread across a series of bands below the capitals with a fictive brickwork design behind the lettering. The manner of signing this stucco work is truly unique, as generally it is stucco mihrabs that are signed, or the end of monumental stucco inscriptions.Footnote 70 The signature of the craftsman was carefully designed to fit in the column capital spaces, and there is a mix of true and fictive hastae in order to retain the rigid knotwork pattern in the upper register of the band. It is only on the two sections on the north wall that the hastae tips have additional incised ornament (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Capitals and inscription band, starting to the right of the mihrab in the south wall and moving anticlockwise round the building.

The decorative patterns along the top of the capitals have escaped the attention of previous scholars, and each pair of columns is topped with a different pattern. The four variants include an angular guilloche at the start, followed by an unusual arrangement of rectangles set flat and diagonally on the south side, with another two, different, continuous patterns on the east and north sides (Fig. 13).

The Stucco Inscription

The stucco inscription band runs along the area just below the muqarnas dome, but because it follows the profile of the wall below, it ties the upper and lower sections of the building together. Externally it can be seen to actually cover the lower portion of the octagonal zone of transition. The inscription has been whitewashed at some point in the intervening centuries, which has decreased the sense of relief and contrast between the inscription and the background scrolls, making the inscription appear flatter than it actually is. Traces of polychromy can be found on the vast majority of contemporaneous stucco inscription bands, and it is probable that the Natanz inscription band also featured polychromy, although any evidence for this is now hidden underneath the layers of whitewash.Footnote 71 Such use of colour on stucco was inherited by Ilkhanid stucco craftsmen from their Seljuq predecessors. However, ongoing research demonstrates some difference in the use of pigments and stucco colouring principles between the Seljuq and the Ilkhanid periods.Footnote 72 The inscription is written in cursive Naskh script, which is large enough and sufficiently clear for it to be read without difficulty when standing in the shrine.Footnote 73

The background scrolls of the Natanz inscription band feature different floral ornaments mimicking palmettes and half-palmettes, which are common motifs of the period. These elements have been heavily perforated in different patterns in order to reduce their visual weight. However, the extensive use of stucco perforation, also seen on the capitals below, reveals a greater richness of incised perforation patterns than is seen on other comparable stucco work from the period in central Iran. The capitals of the columns also retain traces of direct incisions in their design, which the craftsmen employed to outline the design prior to its carving. This frequently occurring phenomenon suggests that the stucco design was produced freehand rather than with the use of stencils. The inscription was produced by carving of at least two layers of stucco and the application of slightly protruding elements. This was a common mode of production of such inscription bands employed by Seljuq and Ilkhanid stucco craftsmen. A close parallel for this method can be seen in the monumental framing inscription on the Öljeitü mihrab in the Masjid-i Jami‘ in Isfahan, dated 710/1310.Footnote 74 From the point of view of stucco carving techniques and the ornamental repertoire of the Natanz shrine, there are closer parallels in the Ilkhanid stucco of the Isfahan region,Footnote 75 rather than Kashan or Qum. The style and technique of production of the monumental inscription band and the engaged columns of the shrine have little in common with the stucco band of the northern iwan in the Friday mosque of the complex, or the nearby Kuche Mir mosque mihrab. These three repertoires also contain different stucco craftsmen signatures, which shows that the three examples of Ilkhanid stucco in the city of Natanz were produced by three different, and presumably itinerant, stucco workshops, rather than by a single locally based one.

The muqarnas Dome

The fact that the stucco inscription band at the top of the walls of the shrine is almost flush with the surface of the thick coat of kahgil and plaster added over the original brick walls appears to preclude the possibility of it and the muqarnas dome above belonging to the same phase of construction as the lower, brick-built, walls. It is probable that the structure originally had a domed roof, but, perhaps due to its collapse at the same time as a large portion of the dome over the nearby octagonal structure collapsed,Footnote 76 a new structural roof and the inner plaster muqarnas ceilingFootnote 77 were probably added at the same time as the dated stucco inscription band, in the early fourteenth century. Extensive restorations on the shrine structure in recent decades have concealed any possible further evidence for understanding the construction of the dome interior. The engaged columns must be the same date as the stucco inscription, as the capitals line up perfectly with the outer edge of the inscription band. The muqarnas cells extend into the northwest corner recess, which is the only one that lacks a brick grille screen, and obscures the brick sub-structure. This can be seen from the outside to have been added at a later date to the original octagonal section of the structure, which adds further credence to the argument that the building originally had a different roof system, and that the muqarnas dome was an Ilkhanid addition that did not form part of the original iteration of the building. It is constructed on the same geometrical principles as the heavily restored muqarnas half-dome of the pishtaq of the khanqah, which provides further evidence for an Ilkhanid date for the muqarnas dome of the shrine, as the khanqah portal can also be firmly assigned to the Ilkhanid period.

The style of the plaster muqarnas dome is almost unknown in Iranian architecture, but it is a masterpiece, built in a style developed in Iraq and Syria in the thirteenth century, though with non-structural plaster inserts. It is of a clear design, employing only 90 and 45 degree angles, with a twelve-pointed star at the apex that has the same diameter as the arch over the larger windows.Footnote 78 The stucco inscription immediately below it refers to the qubba Footnote 79 and not the buq'a, which suggests that it refers to the building of the dome and the installation of the inscription band, rather than to the whole structure, the lower sections of which are clearly earlier. Although it has been extensively rebuilt, the glazed ceramic tile muqarnas semi-dome in the entrance portal of the khanqah was built using the same muqarnas design principle as the dome in the shrine, adding additional credence to the Ilkhanid dating of the stucco muqarnas dome of the building.

The Lustre mihrab

No elements of the lustre mihrab and its associated framing tiles remain in situ, although numerous pieces are preserved in collections around the world,Footnote 80 and the remaining mortar and grout lines give a clear idea of the shapes and sizes of the missing pieces.Footnote 81 The most striking of the surviving pieces is the three-dimensional mihrab hood, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which features Qur'an 17:78 and the date 707/1307-8 (Fig. 14).Footnote 82 It is seemingly unique in the corpus of Ilkhanid mihrabs, with the rest all being flat with relief decoration. Given the date, it may be assumed that the closing off of the southern entrance into the building and the installation of the glazed mihrab and surrounding tiles was all part of the same intervention as the dated stucco inscription of 707/1307-8 and the dado tiles. It is clear that the lustre frieze was not part of the original conception, given the fact that the stucco columns were finished down to the height of the top of the dado, but that within a few months at most, the decision was made to commission the frieze tiles, and thus the need to cut back the base of the stucco columns to incorporate several of them soon arose.

Fig. 14. The upper section of the lustre mihrab niche, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Lustre Inscription Frieze

The best known aspect of the decoration of the shrine in Natanz is the lustre tile epigraphic frieze that ran above the top of the tiled dado, and it is this inscription band that marked the final Ilkhanid decorative intervention in the interior of the shrine.Footnote 83 The fact that the addition of the lustre frieze was one of the last phases of decoration can be demonstrated by looking at the lower section of the decorative engaged columns. They can all be seen to have been shaved down after installation and completion in order to create an angled corner over which the lustre inscription band of tiles could be applied, as can be seen in Fig. 12. None of these tiles remain in situ, and many of them are now dispersed among the major museums with holdings of Islamic art around the world.Footnote 84 The tile frieze features a monumental inscription band quoting verses of Surat al-Insan, but the feature that has attracted the majority of attention is the fact that the background of these tiles features numerous bird images, and that every single one of the birds has been defaced by chipping away the head (Fig. 15). Although there is no firm evidence concerning the date at which the birds were defaced, the fact that all the extant examples have suffered the same fate proves that it occurred while all the tiles were still in situ, and thus probably occurred prior to the middle of the nineteenth century. In addition, a farman of Shah ‘Abbas I, located in the mosque and dated 1615, refers to idolatry in both structures that had to be changed.Footnote 85 In lieu of anything else, this is the closest thing to evidence for the actual date at which the birds were defaced. It is plausible to argue that the iconoclastic defacing of the bird heads occurred at the same time as the interior of the shrine was whitewashed, as is suggested by the same inscription.

Fig. 15. Lustre inscription frieze tile from Natanz, reading wa la shukura[n] (…and no thanks), Qur'an 76:9, with defaced bird heads, now in the British Museum, London.

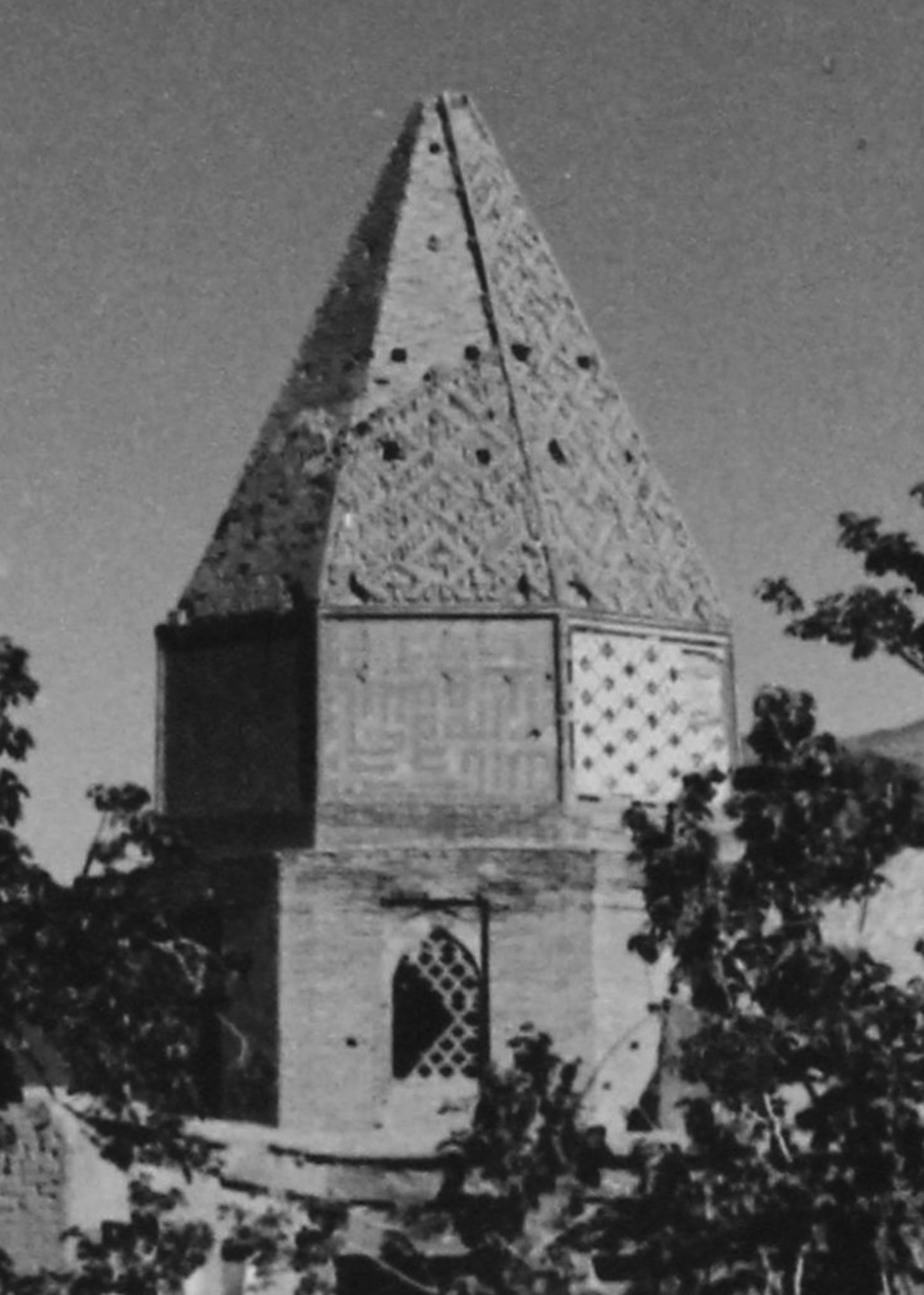

The Shrine Exterior

The upper portion of the exterior of the shrine featured extensive turquoise glazed intarsia forming a variety of patterns on the roof facets and the eight panels below. However, while the pattern on the roof facets appears to be faithful to the original, the most recent restoration has unfortunately resulted in the loss of most of the original patterns on the vertical panels and their replacement with far more simple patterns. Perhaps the greatest loss is the boustrophedonic square Kufic repeats of Allah that were on the southeast facing panel,Footnote 86 between the ones over the entrance and over the mihrab, and which are clearest in a photograph taken by Myron Bement Smith (Fig. 16). There is a marked difference in the brick work of the upper section, with the glazed accents, and the lower section without, which is also indicative of the lower section being largely earlier in date, the numerous repairs and losses notwithstanding.

Fig. 16. Southeast facet of the shrine exterior with square Kufic inscription repeating Allah, prior to restoration. Detail of a photograph taken by Myron Bement Smith.

The first published plan of the site shows a set of stairs going up to the northwest corner of the shrine buildingFootnote 87 (Fig. 2). There remains a mass of brickwork on the corner, which has a far shorter bevel than is seen on the other three corners, and this is the only corner with no brick fretted grille. There appears to be evidence of an additional staircase to a now lost structure, as there are step-like sections with wooden beams visible (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. ‘Abd al-Samad Shrine; northwest aspect of the zone of transition.

The recess for the brick fretted grille over the west entrance has a clear construction break running down one side, with the upper half featuring the fretted opening, and the lower part plain brickwork. This section has the large stucco inscription band attached to the interior, which suggests that in an earlier iteration of the building this whole archway was open, allowing far more light into the building. The other arched sections with grilles in the upper half have either been repaired, or never had a construction break.Footnote 88 There is an octagonal plan, and inside there is an opening, but it does not let in light owing to the brick structure on the corner, possibly added when the khanqah was built. In addition, the octagonal facet on the north-western corner has a low stepped section below the grille, as well as evidence for the lower section having been bricked up, both of which are features lacking from the two corner facets on the east side of the structure.

The Ilkhanid Mosque and Shrine Entrance Portal

There is a significant difference in the original ground level of the entrance to the mosque and the shrine, which also features X-and-O pattern rising joint plugs, and the rest of the façade to the west, which was added in the first quarter of the fourteenth century. The incised joints in the rising joints of the external brickwork around the entrance to the mosque and shrine feature a similar X-and-O pattern as seen inside the tomb, but the overall aesthetic effect is different as they are almost all identical, and are all connected to each other via double incised lines (Fig. 18). This creates a more unified pattern across the entire surface, and there are none of the square epigraphic patterns seen inside the shrine. Although there is a later glazed inscription band referring to the construction of the mosque by Zayn al-Din al-Mastari dated 704/1304-05Footnote 89 and mounted proud of the brickwork, the lower brick section, to a height of about two metres above the top of the doorway, appears to predate the façade built next to it. There is a construction break and a clear shift in alignment to the left of the recessed pointed-arch panel on the face of the entrance portal to the mosque and the shrine.Footnote 90 The section of wall to the right of the door leans significantly towards the octagonal structure, and the surrounding sections of brickwork, including the entire upper section, are of late twentieth-century vintage. When Godard surveyed the complex the entire portal to the point of the construction break to the east was covered in white plaster, and none of the brickwork was visible.Footnote 91

Fig. 18. Incised mortar bed patterns in brickwork on left side of the entrance to the mosque and the shrine in Natanz.

The incised mortar bed and rising joint plugs on the façade of both the entrance portal to the ‘Abd al-Samad shrine, on the left of Fig. 18, and on the nearby Kuche Mir portal,Footnote 92 on the right of Fig. 19, are very similar, but not identical. In both cases the pattern is incised into a layer of plaster,Footnote 93 rather than the actual brick joints and mortar beds as seen in the earlier interior of the shrine. There are variations in the thickness of the fictive courses of brickwork at the ‘Abd al-Samad portal, as well as a single non-standard pattern near the top of the return on the left side of the entrance (Fig. 19 (L)). Although both examples have the same triangular section at the top and bottom of each repeating pattern, a detail which is not seen in earlier Seljuq work, the central circular elements are much smaller, and at times rather angular, in the Kuche Mir examples, as well as being proportionally narrower.Footnote 94 The evidence of vertical incised construction lines and an incomplete pattern mistakenly carved in the wrong placeFootnote 95 suggest that the individual responsible for the Kuche Mir patterns was not the same person who executed the ones at the ‘Abd al-Samad portal, although they both appear to date from around the same time. It is the filling of actual voids between bricks in the Seljuq work, rather than the application of a fictive pattern imitating brickwork in the plaster coating over structural brickwork beneath in the later Ilkhanid work, that that is the fundamental difference between the two styles.Footnote 96

Fig. 19. Ilkhanid rising joint decoration detail of the ‘Abd al-Samad shrine/mosque entrance portal (L), and the entrance portal of the Kuche Mir mosque (R).

The similarity between the plugs and mortar bed decoration, but differences from the related patterns inside the shrine, suggest that both the aforementioned entrances are of similar date, and appear to be from the first Ilkhanid phase of intervention in Natanz.Footnote 97 The construction of the new mosque incorporating the domed structure, and the reconstruction of the shrine, would have necessitated the new access point, as did the major reconstruction work at the Seljuq Kuche Mir mosque nearby. It is probable that the portal of the Friday mosque of the Natanz complex was therefore built during the first phase of Ilkhanid interventions at the site, prior to the construction of the khanqah and minaret. However, it is entirely plausible that it was added in an earlier phase, as the dated inscription runs over the decorative brickwork, and there is no guarantee that it refers to the initial construction, especially as the ground level of the entrance is considerably lower than that of the khanqah next to it.

Post-Ilkhanid Phases in the Shrine

The subsequent periods of modifications of the shrine under the Safavids and Qajars resulted in additional embellishment of the structure of the complex, and an overview of these later interventions is key to the emergence of a fuller understanding of the history of the complex, its function and meaning.

The significant modifications of the Safavid period include the application of mural revetments. In this period the cenotaph of the Shaykh was renewed and given a Safavid look, with the application of cuerda seca tiles donated by Khadija Sultan in 1045/1635-6 (Fig. 20).Footnote 98 The change of aesthetics for the focal point of the shrine with the introduction of cuerda seca tiles, which have a very different ornamental vocabulary, is indicative of the ongoing religious significance of the site to the Safavids.

Fig. 20. Safavid cuerda seca tiles on the cenotaph of the Shaykh, added in 1045/1635-6.

The Application of kahgil and Whitewash

The kahgil, and the whitewashed layer of plaster over it, is only slightly recessed from the front edge of the stucco inscription band. Without the layer of kahgil the inscription band probably would have appeared to project a long way out from the wall and look as if it were overhanging. The column capitals that support the corners of the inscription band also protruded from the supporting walls, in the same manner as the shafts of the columns. The application of the kahgil diminished the contrast in planes between the column capitals and shafts, and the supporting wall surfaces. Originally, the columns did not appear to be engaged in the way that they do, due to the subsequent application of kahgil layers. In the same manner, the kahgil layer made the projection of the mortar bed and the thickness of the tiles less pronounced from the wall than would be the case otherwise. The evidence from the historic inscriptions in the Friday mosque of the Natanz complex suggests that the layers of kahgil, with white plaster covering them, could not have been applied on the surfaces of the ‘Abd al-Samad shrine prior to the Safavid period. However, there are some examples of monuments that testify to the use of layers of plaster on interior surfaces in earlier periods. The mosque of Baba Abdullah in Na'in preserves the interior domed chamber which was covered with layers of plaster, presumably in the Ilkhanid period. An additional argument in favour of dating the kahgil and plaster layers in the Natanz shrine to the Safavid or Qajar period is the fact that the octagonal domed chamber of the Friday mosque of the complex was also covered with plaster layers, perhaps in parallel to the redecoration of its domed area with wall paintings, which are clearly post-Ilkhanid. It is therefore probable that both the shrine and the Friday mosque of the Natanz complex were whitewashed and plastered (on kahgil) at the same time. If so, the kahgil and plaster application represents a fourth phase of intervention in the development of the internal appearance of the monument.

Outside the shrine itself, the northern iwan of the mosque was embellished with wall paintings, which comprise lengthy texts referring to patronage of the complex in the Safavid period and hint at the assertion of political power through patronage of these modifications. It is in this period that the interior of the octagonal pavilion of the Friday mosque of the complex, which already comprised an Ilkhanid lustre mihrab, now no longer extantFootnote 99 and probably contemporary to the tiles in the shrine, was covered with wall paintings.Footnote 100 These wall paintings explicitly covered the dated inscription of 389/998-99, suggesting that there was an attempt to visually unify the entire structure of the mosque using a contemporary Safavid aesthetic (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Buyid inscription dated 389/998-99, with later Safavid painted sections (now partially removed) in the dome of the octagonal tomb structure, now part of the mosque.

Further modifications of the complex took place in the Qajar period as attested by historic inscriptions on the walls of the Friday mosque. Some sections of the lustre mihrab Footnote 101 were still in situ in the shrine in 1915, according to Hussein Muhammad Ibrahim Khan Isfahani, who also noted that other sections were for sale in Isfahan for 20 toman each.Footnote 102

It is clear that the octagonal building was originally a funerary structure, and later became part of a mosque, presumably in the Seljuq period. The installation of the lustre mihrab in the interior of this structure during the Ilkhanid period signalled a change in the functional role from a funerary building into a domed prayer hall. It is probable that the shrine of the Shaykh was a funerary structure from its beginning, but the interventions in the early fourteenth century, including the installation of lustre tiles and the lustre mihrab, transformed it into a proper mazar, with a prayer space for the pilgrims who visited the shrine. The new decorative programme, much like the one at Pir-i Bakran, signalled a slight, but nonetheless important, change to the function of the shrine. This change reflects increasing trends of pilgrimage, which were being encouraged by Ghazan Khan at the time.Footnote 103

Conclusion

Despite all the things that remain unclear, a number of facts concerning the relative chronology of the internal decoration, and some aspects of the external appearance can be known with certainty. The building now known as the shrine of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Samad was originally a structure open on all four sides, with entrances of equal width, presumably datable to the Seljuq period. In this first phase the lower half of the interior wall surfaces featured rectangular X-and-O rising joint plugs, with a limited number of epigraphic square plugs also employed on the lower two meters on the southern and eastern walls. It remains unclear who the original patron of the building was, but it may be assumed that it was built as a funerary structure.

The building was subsequently transformed into the shrine of a renowned Sufi sheikh in the Ilkhanid era. This second phase of decoration consisted of the application of larger decorative columns on the corners of the main walls topped with capitals featuring the name of one of the craftsmen. At the same time the existing blind recesses either side of each entrance were augmented with smaller engaged columns. It was at this point that the southern entrance was bricked up, in order to fill the space with a glazed mihrab. During the same phase of construction the large openings in the octagonal zone of transition were bricked up to the halfway point and the large upper stucco inscription band was added. The other major addition in this phase was the glazed monochrome cross and the eight-pointed star tiled dado. Presumably it was not long after this point, as is suggested by the dates on the tile and the stucco band, that the lustre tile frieze was added above the dado tiles, covering the lower portion of the recently added corner columns and completing the main decorative programme of the shrine.

Subsequently, in the seventeenth century the Safavid tiles were added to the cenotaph, the walls were covered with kahgil and whitewashed, with the stucco inscription band probably being whitewashed at the same time. It was probably also during the same period that the bird heads were all defaced on the lustre tile inscription frieze atop the dado.

What remains less clear is the chronology of the construction of the muqarnas ceiling, which is almost certainly not Seljuq, and was probably added prior to, but in the same development phase as, the dated stucco inscription band of 707/1307-08.Footnote 104 As with so many pre-modern sites in Iran, there remain far more questions than answers, but at least a little more light has now been focused on some of the aspects of the development of this enigmatic complex.