No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

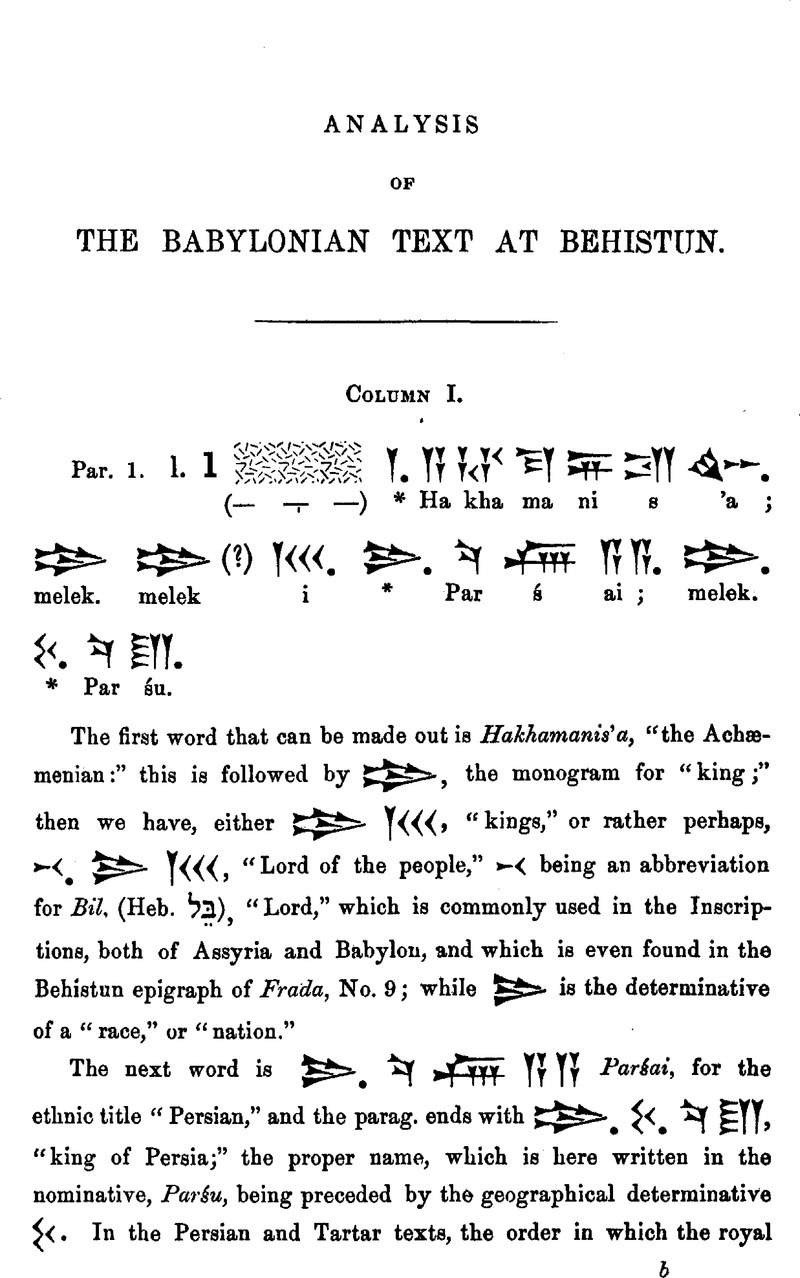

Analysis of the Babylonian text at Behistun.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Prelims

- Information

- Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society , Volume 14: Memoir on the Babylonian and Assyrian Inscriptions , January 1851 , pp. i - civ

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Asiatic Society 1851

References

page iii note 1 This is incorrectr. The expression ![]()

![]() which occurs at Nakhsh-i-Rustam, and generally in the Inscriptions of Xerxes, merely signifies “king of many kings,”

which occurs at Nakhsh-i-Rustam, and generally in the Inscriptions of Xerxes, merely signifies “king of many kings,” ![]() being the pronoun or article used to connect the nominative and genitive.

being the pronoun or article used to connect the nominative and genitive.

page iii note 2 On a further examination and comparison of the Khursabad Inscriptions, I find that the title of melek was especially applied to the rulers of the Khatti or Hittites, who held the Syrian cities of Carchemish, Hamath, Bambyce, and Ashdod. The Khursabad king, at least, always styles himself “conqueror of the maliki” of these cities, and in no other passage do I find the title used. Compare with the phrase quoted in the text, the analogous passages of the Pavement and Bull Inscriptions of Khursabad, (such as 16. 23; 36. 14, &c), and remark for the title malik, the varizant orthography of ![]() sing. and

sing. and ![]() or

or ![]() plural. This discovery, of course, tends to discredit the reading of melek for the Assyrian

plural. This discovery, of course, tends to discredit the reading of melek for the Assyrian ![]() or

or ![]() , and to suggest the uniform adoption of sarru.

, and to suggest the uniform adoption of sarru.

page iv note * The vowel used as the 3rd radical of this verb is, I now think, substituted for a Hebrew i, gabu standing for gabal, which must be compared with ![]() .

.

page vii note * As these sheets are passing through the press, it has occurred to me, that ![]() and

and ![]() are in all probability to be compared with

are in all probability to be compared with ![]() the i and u replacing a primitive l, and the letter

the i and u replacing a primitive l, and the letter ![]() or

or ![]() which interchanges with

which interchanges with ![]() and

and ![]() having a guttural pronunciation like the Arabic

having a guttural pronunciation like the Arabic ![]()

![]() is at any rate used like

is at any rate used like ![]() and

and ![]() like

like ![]() .

.

page vii note 1 In the phrase— ![]() “Which from antiquity, the kings, my fathers . . . . . . . had built.”

“Which from antiquity, the kings, my fathers . . . . . . . had built.”

page viii note 1 The letter ![]() has, however, in addition to its normal value of is, the secondary power of mil or vil, which nearly assimilates with

has, however, in addition to its normal value of is, the secondary power of mil or vil, which nearly assimilates with ![]() so that very possibly the term in question may, after all, be read as viltu or valtu. On the other hand,

so that very possibly the term in question may, after all, be read as viltu or valtu. On the other hand, ![]() “from,” is sometimes replaced by

“from,” is sometimes replaced by ![]() as if the pronunciation were yastu. In other passages, the particle is represented by

as if the pronunciation were yastu. In other passages, the particle is represented by ![]() ta, or

ta, or ![]() and sometimes even by

and sometimes even by ![]() .

.

page ix note 1 See Nakhsh-i-Rustam, 1. 11, ![]() “they held;” and I. 26,

“they held;” and I. 26, ![]() he held,” or “possessed.” These terms might certainly be read yakhaslu, the root khasal being identical with

he held,” or “possessed.” These terms might certainly be read yakhaslu, the root khasal being identical with ![]() and he sign

and he sign ![]() as the monogram for “a family,” having the phonetic power of yakhas. At any rate. the initial sound must be ya.

as the monogram for “a family,” having the phonetic power of yakhas. At any rate. the initial sound must be ya.

page x note 1 See also ![]() “from former times.” Khurs., 163. 14.

“from former times.” Khurs., 163. 14.

page xi note 1 The letter ![]() in this form represents the conjugational characteristic, and the termination in u marks, of course, the plural number, like the Hebrew

in this form represents the conjugational characteristic, and the termination in u marks, of course, the plural number, like the Hebrew ![]() It remains to be ascertained, however, whether there is any actual grammatical difference between the masculine plural endings in simple u, and those to which the

It remains to be ascertained, however, whether there is any actual grammatical difference between the masculine plural endings in simple u, and those to which the ![]() is attached in lieu of a primitive n, or whether the distinction is merely orthographical.

is attached in lieu of a primitive n, or whether the distinction is merely orthographical.

page xii note 1 The word ![]() I find, occurs in Genesis xi. 6, with the signification of “thinking,” and this word may very well be of cognate origin with the Cuneiform

I find, occurs in Genesis xi. 6, with the signification of “thinking,” and this word may very well be of cognate origin with the Cuneiform ![]() .

.

page xiii note * On further consideration, I am pretty well satisfied that ![]() and

and ![]() are cognate forms, pronounced yaddinu and yaddanu, and derived from a root danan, of the

are cognate forms, pronounced yaddinu and yaddanu, and derived from a root danan, of the ![]() class. (Compare

class. (Compare ![]() from (

from (![]() ). There were probably two roots in Assyrian, danan and dun, immediately cognate, and both signifying “to give.” They were extensively used, and one of their principal derivatives was the word for “law,” or “religion,” as a thing given. Compare dáta,

). There were probably two roots in Assyrian, danan and dun, immediately cognate, and both signifying “to give.” They were extensively used, and one of their principal derivatives was the word for “law,” or “religion,” as a thing given. Compare dáta, ![]() from dá “to give.”) This word is written in Assyrian

from dá “to give.”) This word is written in Assyrian ![]() or

or ![]() danan; but in Babylonian

danan; but in Babylonian ![]() dina; like the Hebrew

dina; like the Hebrew ![]() and Arabic

and Arabic ![]() .

.

page xiv note 1 The term ![]() is constantly used in Babylonian proper names as an adjunct to the names of gods; the meaning of such names being “granted by Nebo,” “granted by Bel,” &c, like the Mithridates of old, or the modern synonyms, Ata Ullah in Arabic; Khodadád in Persian; and Tangri Verdi in Turkish. See the names in Grotefend's Plate, Zeits., vol. II. p. 177, and remark also, that the name of

is constantly used in Babylonian proper names as an adjunct to the names of gods; the meaning of such names being “granted by Nebo,” “granted by Bel,” &c, like the Mithridates of old, or the modern synonyms, Ata Ullah in Arabic; Khodadád in Persian; and Tangri Verdi in Turkish. See the names in Grotefend's Plate, Zeits., vol. II. p. 177, and remark also, that the name of ![]() is found in one of the Cyprus legends. Ges. Men. Phoen., p. 143.

is found in one of the Cyprus legends. Ges. Men. Phoen., p. 143.

page xvii note 1 I have lately met with the name of Susa, (written ![]() in an Ins.) of the time of Darius Hystaspes, discovered by Col. Williams among the ruins of the city, and I have also found the same place noticed in the campaigns of an early monarch of Assyria, under the title of

in an Ins.) of the time of Darius Hystaspes, discovered by Col. Williams among the ruins of the city, and I have also found the same place noticed in the campaigns of an early monarch of Assyria, under the title of ![]() Susan.

Susan.

page xviii note 1 There is also an Eastern tribe of ![]() Aribi, frequently spoken of in the Khursabad Inscriptions, in connexion with Media, but they can hardly be Arabs.

Aribi, frequently spoken of in the Khursabad Inscriptions, in connexion with Media, but they can hardly be Arabs.

page xix note 1 The Babylonian term is thus absolutely the same as the Latin word insula which also signifies “in the sea.”

page xix note 2 The Sanscrit ![]() “green,” has produced on the one side, the Zend zarayo, Persian daraya, &c, applied to “the sea,” and on the other the Latin “viridis,” in French “vert,” almost an identical term with the Babylonian varrat.

“green,” has produced on the one side, the Zend zarayo, Persian daraya, &c, applied to “the sea,” and on the other the Latin “viridis,” in French “vert,” almost an identical term with the Babylonian varrat.

page xix note 3 The discovery that the phrase as varrati, or tya darayahyá, does not refer to the names of Saparda and Yuua, but denotes an independent Satrapy, removes all plausibility from my proposed identification of the former of these names with Σπάρτα. I am now obliged to agree with those who identify Saparda with Lydia, or rather, perhaps, with that portion of Asia Minor west of Cappadocia, but I still see no sufficient grounds for connecting a great geographical name, such as the Saparda of the Inscriptions, with the obscure ![]() of Obadiah. Neither Saparda nor Ionia, I think, are mentioned in the Inscriptions of Assyria, though there is the nearly similar name of

of Obadiah. Neither Saparda nor Ionia, I think, are mentioned in the Inscriptions of Assyria, though there is the nearly similar name of ![]() Yavnai, for a maritime people of Phœnicia, corresponding with the

Yavnai, for a maritime people of Phœnicia, corresponding with the ![]() of Scripture. (2 Chr. xxvi. 6. &c.)

of Scripture. (2 Chr. xxvi. 6. &c.)

page xx note 1 The first syllable in Paropanisus is certainly ![]() paruh, “a mountain;” the etymology of the latter part of the name is more obscure.

paruh, “a mountain;” the etymology of the latter part of the name is more obscure.

page xxiii note 1 Haga, at any rate, may be compared immediately with the Latin hio, and with the Pushtoo hagha, both as to sense and sound, although these forms are supposed to be intimately connected with the Indo-Germanic pronominal system. (Compare Sans. ![]() Zend

Zend ![]() &c.)

&c.)

page xxiii note 2 ![]() as an ideograph for a country, as well as a phonetic power, is thus often replaced by mat. See the orthography of the name of the city of Hamath, and compare

as an ideograph for a country, as well as a phonetic power, is thus often replaced by mat. See the orthography of the name of the city of Hamath, and compare ![]() Khur., 152. 8, with

Khur., 152. 8, with ![]() “this country,” in Khursabad, 129. 5. For “this my country,” we have also,

“this country,” in Khursabad, 129. 5. For “this my country,” we have also, ![]() matiya haga, in Nakhsh-i-Rustam, 1.33; but in Westergaard's H., Is. 8 and 16,

matiya haga, in Nakhsh-i-Rustam, 1.33; but in Westergaard's H., Is. 8 and 16, ![]() and

and ![]() are used in apposition to each other, as if they were different terms.

are used in apposition to each other, as if they were different terms.

page xxiv note 1 This is the feminine singular of the 3rd person, the feminine plural being yakkira'.

page xxvi note 1 The analogy between the forms ![]() attur, or

attur, or ![]() aturu, and

aturu, and ![]() adduk, or

adduk, or ![]() aduku, would lead to a suspicion that the root of the substantive verb might be tarar like dakak, and that the duplication might be similar to the Daghesli used in Hebrew with the first radical of one of the future forms of the verba geminantia. Compare

aduku, would lead to a suspicion that the root of the substantive verb might be tarar like dakak, and that the duplication might be similar to the Daghesli used in Hebrew with the first radical of one of the future forms of the verba geminantia. Compare ![]() for

for ![]() This explanation is, at any rate, preferable to that given in page xv.

This explanation is, at any rate, preferable to that given in page xv.

page xxvi note * In Mr. Layard's new Inscriptions, I have met with numerous examples of this plural ending, which seems, in fact, to be used indifferently with the contracted form in u.

page xxvi note 2 It seems to me impossible that the letter ![]() can here represent its full power of nu, as that termination is unknown to any of the plural forms, either in Hebrew or Arabic.

can here represent its full power of nu, as that termination is unknown to any of the plural forms, either in Hebrew or Arabic.

page xxvii note 1 If the derivation of this term from the root ![]() be correct, the nasal, of course, must be explained as in Chaldee, by the Daghesh forte being resolved, a curious illustration being thus obtained of the applicability to the Babylonian of the orthographical rules proper to the Hebrew and Chaldee.

be correct, the nasal, of course, must be explained as in Chaldee, by the Daghesh forte being resolved, a curious illustration being thus obtained of the applicability to the Babylonian of the orthographical rules proper to the Hebrew and Chaldee.

page xxviii note 1 On a further consideration, I am satisfied that this phrase should be read ![]() ana apusu yabbussu', “they did the doing,” according to a system of redundant expression which the Babylonian particularly affected.

ana apusu yabbussu', “they did the doing,” according to a system of redundant expression which the Babylonian particularly affected.

page xxviii note 2 Ana sasu yapnusu' might signify “to that they turned,” the verb employed corresponding to the Hebrew ![]() The term apnusu, however, is, I think, again used in line 11, and the context will there require a verb similar to the Latin ago.

The term apnusu, however, is, I think, again used in line 11, and the context will there require a verb similar to the Latin ago.

page xxx note 1 This name is written phonetically as ![]() a form which we are certainly warranted, on the united authority of ancient and modern languages, in reading Nabu, rather than Nabiuv.

a form which we are certainly warranted, on the united authority of ancient and modern languages, in reading Nabu, rather than Nabiuv.

page xxx note 2 The Piël form of ![]() signifies, “to engrave,” or “carve,” or “sculpture,” and would suit the Assyrian verh therefore sufficiently well. I doubt, however, the interchange of the Hebrew

signifies, “to engrave,” or “carve,” or “sculpture,” and would suit the Assyrian verh therefore sufficiently well. I doubt, however, the interchange of the Hebrew ![]() with the Babylonian k.

with the Babylonian k. ![]() merely means “to cut in pieces,” and is but remotely connected, therefore, as far as sense is concerned, with the verb in question.

merely means “to cut in pieces,” and is but remotely connected, therefore, as far as sense is concerned, with the verb in question.

page xxxiii note 1 Yaddinu will more probably come from danan, as yadduku comes from dakak; (compare ![]() from

from ![]() ). The connexion, indeed, between din and danan is further shown, by the common use in Assyrian of

). The connexion, indeed, between din and danan is further shown, by the common use in Assyrian of ![]() danan, for “law,” or “religion,” answering to the Arabic

danan, for “law,” or “religion,” answering to the Arabic ![]() which is, of course, etymologically identical with the Hebrew

which is, of course, etymologically identical with the Hebrew ![]() . In the Inscriptions lately brought by Mr. Layard from Assyria, numerous examples occur of the indifferent orthography of

. In the Inscriptions lately brought by Mr. Layard from Assyria, numerous examples occur of the indifferent orthography of ![]() and

and ![]() danani, for the word signifying “laws,” a further proof being thus afforded of the derivation of the noun from the root danan, which has supplied us with the future forma

danani, for the word signifying “laws,” a further proof being thus afforded of the derivation of the noun from the root danan, which has supplied us with the future forma ![]() or

or ![]() yaaddinu or yaddanu, “he gave,” or “granted.”

yaaddinu or yaddanu, “he gave,” or “granted.”

page xxxv note * In Mr. Layard's new Inscriptions ![]() is repeatedly put for lapani, “from.”

is repeatedly put for lapani, “from.”

page xxxvi note * But see the new foot-note to p. xii.

page xxxviii note * Consequent on the discovery that ![]() and

and ![]() are mere variant orthographies for the same word, I would now propose to refer all these forms to a root danan, signifying primarily, “to give,” but used like the Hebrew

are mere variant orthographies for the same word, I would now propose to refer all these forms to a root danan, signifying primarily, “to give,” but used like the Hebrew ![]() to express other meanings, such as “to rule,” “to judge,” “to protect,” or “defend.” Danú, “help,” may thus be connected with the idea of “protection:” danu, applied to a king, may mean “ruling,” or “governing,” (see 1 Sam. ii. 10; Zech. iii. 7, &c): danát, applied to cities, may indicate “walled cities,” or “places of defence.” The same word may also denote “laws,” or “things given,” and limit hudinu, as in the last example here quoted, may be translated, “I gave as dependencies.” The two preceding examples are very doubtful:

to express other meanings, such as “to rule,” “to judge,” “to protect,” or “defend.” Danú, “help,” may thus be connected with the idea of “protection:” danu, applied to a king, may mean “ruling,” or “governing,” (see 1 Sam. ii. 10; Zech. iii. 7, &c): danát, applied to cities, may indicate “walled cities,” or “places of defence.” The same word may also denote “laws,” or “things given,” and limit hudinu, as in the last example here quoted, may be translated, “I gave as dependencies.” The two preceding examples are very doubtful: ![]() seems rather to signify “he threw off allegiance.”

seems rather to signify “he threw off allegiance.”

page xliii note * I now prefer explaining forms in which the first radical is doubled, such as yattur, yadduku, yaddinu, by supposing the roots to be of the ![]() class.

class.

page xliv note * As we have masc plur. ![]() madut; fem. plur.

madut; fem. plur. ![]() madet, so we have masc plur.

madet, so we have masc plur. ![]() hakannut; fem. plur.

hakannut; fem. plur. ![]() haganet. The undoubted connexion, indeed, of these last terms, leads me to suspect that the letters

haganet. The undoubted connexion, indeed, of these last terms, leads me to suspect that the letters ![]() and

and ![]() must be placed in the same phonetic category, either the sign

must be placed in the same phonetic category, either the sign ![]() having the secondary power of kon, or the sign

having the secondary power of kon, or the sign ![]() being valued in certain positions as ga. I leave this point, however, for subsequent research.

being valued in certain positions as ga. I leave this point, however, for subsequent research.

page xlviii note 1 That the root dakak was in use as well as duk is shown by the form of the participle in Assyrian, which is usually written ![]() vadakik, or

vadakik, or ![]() vadakiku. See Brit. Mus., 17, 8; 76, 5; and Khur. revers, passim.

vadakiku. See Brit. Mus., 17, 8; 76, 5; and Khur. revers, passim.

page xlviii note 2 It would of course be more correct etymologically to translate azadá “unknown,” supposing the initial a to be the privative particle; and in this particular passage such a translation would suit the Scythic and Babylonian texts without the necessity of supplying the word niya; but in the Nakhsh-i-Rustam passages, where a negative signification is impossible, azadá must be rendered almost certainly by “known;” and I am obliged, therefore, to regard the initial a as a mere unmeaning prosthesis.

page xlix note 1 This word may rather, perhaps, be read yavvaldakka for yanvaldakka, and may be identified with the passive causative form of the root vadak. There are good grounds, indeed, for reading ![]() as val, rather than va, and there are many examples of the introduction of the l in Babylonian, in order to give a causative power to the verb. I would suggest, therefore, the gradation of vadak, “to know;” valdak, “to make known;” nivaldak, “to be made known;” and would translate yavvaldakka by “it shall be made known to thee.”

as val, rather than va, and there are many examples of the introduction of the l in Babylonian, in order to give a causative power to the verb. I would suggest, therefore, the gradation of vadak, “to know;” valdak, “to make known;” nivaldak, “to be made known;” and would translate yavvaldakka by “it shall be made known to thee.”

page l note 1 I should have expected barataniya for the infinive form; but there may have been an initial a, answering to the Sanscrit ![]() and preserved in the modern Persian,

and preserved in the modern Persian, ![]() awardan, “to bring.”

awardan, “to bring.”

page l note 2 But see the note on the last page.

page lii note * I now read ![]() as qabi, and compare

as qabi, and compare ![]() although it must be confessed that that particle will hardly suit the context of the present passage.

although it must be confessed that that particle will hardly suit the context of the present passage.

page lii note 1 The imperfect Persian phrase in the Nakhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, 1. 52, pátuwá hachá sara, — —, “protect from decay,” is translated in Babylonian, by ![]()

![]() liuṣṣr anni lipani mivva biyasi; and the Scythic correspondent for this word, biyasi,

liuṣṣr anni lipani mivva biyasi; and the Scythic correspondent for this word, biyasi, ![]() is the same which answers to the Persian thadaya, “decay,” in line 58 of the same Inscription.

is the same which answers to the Persian thadaya, “decay,” in line 58 of the same Inscription.

page liii note * The connexion of ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() having suggested the attribution to the letter

having suggested the attribution to the letter ![]() of the secondary power of ga or ka, I would now propose to read

of the secondary power of ga or ka, I would now propose to read ![]() as yatlakka, and to explain it as the Tiphal form of a root answering to

as yatlakka, and to explain it as the Tiphal form of a root answering to ![]() “to go,” the duplication being similar to that which we also find in another Tiphal form yatbavva, and the first radical having fallen away as a weak letter, before the conjugational characteristic; or it might be better, considering the guttural

“to go,” the duplication being similar to that which we also find in another Tiphal form yatbavva, and the first radical having fallen away as a weak letter, before the conjugational characteristic; or it might be better, considering the guttural ![]() and its congener

and its congener ![]() to be especially appropriated to gutturals of the

to be especially appropriated to gutturals of the ![]() class, to derive yatlaqqa from

class, to derive yatlaqqa from ![]() In Tiphal forms of

In Tiphal forms of ![]() indeed, the conjugational characteristic would require, I think, to be doubled, to compensate for the lapse of the first radical.

indeed, the conjugational characteristic would require, I think, to be doubled, to compensate for the lapse of the first radical.

page lv note * I am now rather inclined to think that there is a distinction between ![]() and

and ![]() the former being sounded as ya with the short vowel, and the latter as yá with the long.

the former being sounded as ya with the short vowel, and the latter as yá with the long.

page lvii note 1 Perhaps, however, yatba and yatbuni mean in Assyrian, “arising,” rather than “coming.” I should wish, indeed, to derive these forms from a root tabah or dabah (for tabu or dabu), but the orthography of the cognate form of yatbavva renders such a derivation impossible, for the duplication would then fall on the 3rd radical, which is entirely opposed to the rules of Hebrew conjugation.

page lviii note * There can be no doubt, but that ![]() in this passage and in many others, signifies “there,” or “that place.” meanings which it is very difficult to connect with the Chaldee

in this passage and in many others, signifies “there,” or “that place.” meanings which it is very difficult to connect with the Chaldee ![]() nevertheless, I shall still continue to read

nevertheless, I shall still continue to read ![]() as qabi, until some more suitable explanation can be given.

as qabi, until some more suitable explanation can be given.

page lviii note 1 No great weight after all attaches to this example, for it seems pretty certain that the sign ![]() can be used instead of

can be used instead of ![]() to represent the plural termination of nouns without any reference to its phonetic value. Of more importance would be the phrase, answering to “then,” and expressed by

to represent the plural termination of nouns without any reference to its phonetic value. Of more importance would be the phrase, answering to “then,” and expressed by ![]() or

or ![]() (meaning, probably, “in die illo,” or “in diebus illis;”) for as the letter

(meaning, probably, “in die illo,” or “in diebus illis;”) for as the letter ![]() is a labial congener with

is a labial congener with ![]() it would seem almost certain that the preceding

it would seem almost certain that the preceding ![]() must end in a homogeneous consonant, the reading, in fact, being aś yommu su, or aś yommi su; but, on the other hand, it is quite unusual to find the pronoun su applying indifferently to the singular and plural number, and the orthography, moreover, sometimes occurs of

must end in a homogeneous consonant, the reading, in fact, being aś yommu su, or aś yommi su; but, on the other hand, it is quite unusual to find the pronoun su applying indifferently to the singular and plural number, and the orthography, moreover, sometimes occurs of ![]() which can hardly be read aśs yommi, as the

which can hardly be read aśs yommi, as the ![]() represents exclusively the sound of bi.

represents exclusively the sound of bi.

page lx note 1 Since writing the above, I have examined some Assyrian Calendars brought by Mr. Layard from Nineveh, and I find that the year did consist of twelve lunations, of thirty days each. The same name, therefore, must be represented by variant monograms.

page lx note 2 With this indication, I would venture also to compare ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() or

or ![]() with which they certainly coincide very nearly in use, and would thus assign to the letter

with which they certainly coincide very nearly in use, and would thus assign to the letter ![]() or

or ![]() the phonetic power of qa.

the phonetic power of qa.

page lxii note 1 In the rendering of proper names, at any rate, we see that the Babylonians doubled the consonants as they pleased, without any regard to the orthography of the Persian originals; and it would be too much, therefore, to expect from them a rigorous attention to grammatical rule in representing their own language.

page lxiii note 1 I can hardly believe that ![]() really represents the particle

really represents the particle ![]() notwithstanding the applicability of such an explanation to this phrase, for I have never met with min, “from,” written phonetically in any other passage of the Inscription. I should rather suspect

notwithstanding the applicability of such an explanation to this phrase, for I have never met with min, “from,” written phonetically in any other passage of the Inscription. I should rather suspect ![]() to represent a noun in combination with the suffix of the 3rd person. It is possible, indeed, as

to represent a noun in combination with the suffix of the 3rd person. It is possible, indeed, as ![]() and

and ![]() are both polyphone signs, that the true reading of the word may be nissalsu, (Hebrew

are both polyphone signs, that the true reading of the word may be nissalsu, (Hebrew ![]() ); and that the phrase may signify “he was delivered by death,” or his deliverance was dying.”

); and that the phrase may signify “he was delivered by death,” or his deliverance was dying.”

page lxvi note 1 I observe, in many passages of this Inscription, an extraordinary similarity between suffixed pronouns of the 3rd person and forms of the substantive verb, a similarity which strikingly resembles the presumed relationship in Hebrew between the pronouns ![]() and

and ![]() and the verbs

and the verbs ![]() and

and ![]() In line 3,

In line 3, ![]() sun, seems to be used for “have been.” The common phrase

sun, seems to be used for “have been.” The common phrase ![]() which precedes the dates, may mean “these were.”

which precedes the dates, may mean “these were.” ![]() sina, in the same way, in line 10C, replaces the substantive verb in the fem. plural, and

sina, in the same way, in line 10C, replaces the substantive verb in the fem. plural, and ![]() siya, in the present passage must, I think, be similarly explained as standing for the fem. sing. I conjecture, accordingly, that the suffix of the 3rd person, agreeing with its antecedent in gender and number, was optionally used in Babylonian for the substantive verb; and I thus define

siya, in the present passage must, I think, be similarly explained as standing for the fem. sing. I conjecture, accordingly, that the suffix of the 3rd person, agreeing with its antecedent in gender and number, was optionally used in Babylonian for the substantive verb; and I thus define ![]() siya as the suffix of the 3rd person singular, answering to the Hebrew

siya as the suffix of the 3rd person singular, answering to the Hebrew ![]() , and put in the feminine gender to agree with the nominative melkut or sarrut, “empire.”

, and put in the feminine gender to agree with the nominative melkut or sarrut, “empire.”

page lxix note 1 Etymologically it would be proper to translate manma by “aliquis,” rather than by “nemo,” for the Hebrew ![]() , which is the original of the Arabic

, which is the original of the Arabic ![]() , has a mere indefinite sense, corresponding, in fact, exactly with the indefinite affix chiya, in the compound pronoun chishchiya, which is the Persian equivalent to

, has a mere indefinite sense, corresponding, in fact, exactly with the indefinite affix chiya, in the compound pronoun chishchiya, which is the Persian equivalent to ![]() but, on the other hand, I observe that manma is only employed where the action is negative, and the double negative is quite agreeable to Semiti usage.

but, on the other hand, I observe that manma is only employed where the action is negative, and the double negative is quite agreeable to Semiti usage.

page lxix note 2 For the cursive rendering of this line, see Bellino's Cyl., side 2, line 4.

page lxx note 1 For the Piël participles, singular ![]() hvanakkim, plur.

hvanakkim, plur. ![]() hvanakkimu; see East Ind. Ins., col. 7, 1. 21, and 8, 1. 18.

hvanakkimu; see East Ind. Ins., col. 7, 1. 21, and 8, 1. 18.

page lxx note 2 The letter ![]() is a variant for

is a variant for ![]() as the monogram for “a house”; and it has thus several phonetic values, such as bit, mal, &c, in common with that sign; but I suspect that the two characters have also independent powers. At any rate, the verb

as the monogram for “a house”; and it has thus several phonetic values, such as bit, mal, &c, in common with that sign; but I suspect that the two characters have also independent powers. At any rate, the verb ![]() which occurs in this passage, cannot possibly have the same meaning as the term

which occurs in this passage, cannot possibly have the same meaning as the term ![]() , used in line 22 of the Nakhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, which, however, if

, used in line 22 of the Nakhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, which, however, if ![]() and

and ![]() were phonetically identical, would have every appearance of being a cognate Ifta'al form.

were phonetically identical, would have every appearance of being a cognate Ifta'al form.

page lxx note 3 Mons. Oppert's amended readings of the Behistun Inscription are now in the course of publication in the Journal Asiatique. His learning is undoubted, and some of his corrections are important; but a large portion of his criticism is to be found in my Behistun Vocabulary, the 1st volume of which was published in 1849, but of the very existence of which Mons. Oppert seems, nevertheless, to be completely ignorant.

page lxxi note 1 As there appear to have been no signs of the ![]() class of sibilants, appropriated to the syllables yaś and vaś, the corresponding signs of the

class of sibilants, appropriated to the syllables yaś and vaś, the corresponding signs of the ![]() class (namely,

class (namely, ![]() and

and ![]() ) were necessarily used in conjunction with

) were necessarily used in conjunction with ![]() and

and ![]() but for the syllable aś there was a distinct character

but for the syllable aś there was a distinct character ![]() ; and wherever, accordingly, we find the

; and wherever, accordingly, we find the ![]() assimilating with the śa, śi or śu, (as in this word

assimilating with the śa, śi or śu, (as in this word ![]() ) it must be considered an instance of careless orthography.

) it must be considered an instance of careless orthography.

page lxxii note 1 The follovring are the materials I have collected for determining the power of ![]() In the annals of the Koyunjik king, it stands for the numeral 3. In the Khursabad Inscriptions, the term

In the annals of the Koyunjik king, it stands for the numeral 3. In the Khursabad Inscriptions, the term ![]() commonly interchanges with

commonly interchanges with ![]() The word

The word ![]() signifies “he dared.” The standard epithet applied to the god

signifies “he dared.” The standard epithet applied to the god ![]() at Khursabad is

at Khursabad is ![]() The sign

The sign ![]() is also a common element in Babylonian names; compare

is also a common element in Babylonian names; compare ![]() “Nebo —, the son of Nalazu,”(?) referring to the chief placed by Esar Haddon in charge of Babylonia, (British Museum, 22. 50:) and the Babylonian king,

“Nebo —, the son of Nalazu,”(?) referring to the chief placed by Esar Haddon in charge of Babylonia, (British Museum, 22. 50:) and the Babylonian king, ![]() or

or ![]() “— — Merodach, the son of

“— — Merodach, the son of ![]() ” who gave tribute to the Obelisk king. (See Brit. Mus., 46, 17, and 15, 29.) The name of this king has certainly a Btriking resemblance to the Mesessimordacus of the Canon of Ptolemy; but, on the other hand, chronologically, the identification seems impossible; and I have no authority from etymological sources for thus attributing to the sign

” who gave tribute to the Obelisk king. (See Brit. Mus., 46, 17, and 15, 29.) The name of this king has certainly a Btriking resemblance to the Mesessimordacus of the Canon of Ptolemy; but, on the other hand, chronologically, the identification seems impossible; and I have no authority from etymological sources for thus attributing to the sign ![]() the value of sas.

the value of sas.

page lxxiii note 1 ![]() exchanges with

exchanges with ![]() or

or ![]() , as the correspondent for hamaranam, “battle,” throughout the Behistun Inscription.

, as the correspondent for hamaranam, “battle,” throughout the Behistun Inscription. ![]() salmanu haganut, “these images” (compare Hebrew

salmanu haganut, “these images” (compare Hebrew ![]() Arab.

Arab. ![]() ) occurs in Behistun Inscription, line 106, where, however, the printed text has an erroneous reading; and for vusalkha, “victorious,” see the titles of Sargina, [Shalmaneser] in B. M., 33. 1. 4.

) occurs in Behistun Inscription, line 106, where, however, the printed text has an erroneous reading; and for vusalkha, “victorious,” see the titles of Sargina, [Shalmaneser] in B. M., 33. 1. 4.  I derive vusalkha, of course, from

I derive vusalkha, of course, from ![]() .

.

page lxxiii note 2 As there are several characters which thus fluctuate between the l and s, there would seem to be some phonetic law connecting the two classes. At any rate, ![]() and

and ![]() interchange repeatedly:

interchange repeatedly: ![]() is sometimes put for

is sometimes put for ![]() seems also to have the power of as, and I am half inclined to think that what I have hitherto called Liphal and Iltaphal forms, are in reality Shaphel and Istaphal (for Hiphil and Hithpael); the sign

seems also to have the power of as, and I am half inclined to think that what I have hitherto called Liphal and Iltaphal forms, are in reality Shaphel and Istaphal (for Hiphil and Hithpael); the sign ![]() having the power of as as well as of al; for amongst other examples, I observe, that

having the power of as as well as of al; for amongst other examples, I observe, that ![]() in the 1st pera, seems to answer to

in the 1st pera, seems to answer to ![]() in tlie 3rd; and that

in tlie 3rd; and that ![]() and

and ![]() belong apparently to the same tense of the same verb. All this is very puzzling, and can only yield to careful and continued research.

belong apparently to the same tense of the same verb. All this is very puzzling, and can only yield to careful and continued research.

page lxxiv note 1 The sign ![]() or

or ![]() is constantly used in the Assyrian Inscriptions as determinative of “a title.” Compare the word

is constantly used in the Assyrian Inscriptions as determinative of “a title.” Compare the word ![]() “a general,” (rendered by the Hebrews as

“a general,” (rendered by the Hebrews as ![]() ;) also

;) also ![]()

![]() ; and perhaps,

; and perhaps, ![]() .

.

page lxxx note 1 The ya in yazaṣ may be taken as a middle form between ![]() and

and ![]() at any rate, examples of the yod interchanging with gutturals are not uncommon; while the Babylonian z is known to be a frequent substitute for the dental, as in the orthography of Barziya for the Persian Bardiya.

at any rate, examples of the yod interchanging with gutturals are not uncommon; while the Babylonian z is known to be a frequent substitute for the dental, as in the orthography of Barziya for the Persian Bardiya.

page lxxxii note 1 I may here add a few words on the pronoun of the 3rd person. The masc. singular is ![]() the feminine

the feminine ![]() siva

siva ![]() The masc. plural is

The masc. plural is ![]() sunut; the fem. plural,

sunut; the fem. plural, ![]() sinat. The abbreviated forms used as suffixes are, masculine

sinat. The abbreviated forms used as suffixes are, masculine ![]() or

or ![]() su, singular;

su, singular; ![]() sun, plural: feminine

sun, plural: feminine ![]() (?) si, singular;

(?) si, singular; ![]() sin, plural. Sunuti and sinati are used also for the oblique cases of the plural pronoun, and sunu and sina frequently take the place of sun and sin, for the plural suffix, without involving, I think, any grammatical distinction. With regard to the distinction between ut and at, for the masculine and feminine gender of plural, I may observe that a kindred rule of orthography seems to pervade the whole structure of the Babylonian grammar; we have thus, masculine

sin, plural. Sunuti and sinati are used also for the oblique cases of the plural pronoun, and sunu and sina frequently take the place of sun and sin, for the plural suffix, without involving, I think, any grammatical distinction. With regard to the distinction between ut and at, for the masculine and feminine gender of plural, I may observe that a kindred rule of orthography seems to pervade the whole structure of the Babylonian grammar; we have thus, masculine ![]() madut, fem.

madut, fem. ![]() . madet, “many;” —masc.

. madet, “many;” —masc. ![]() haganut, fem.

haganut, fem. ![]() haganet, “these;”—masculine

haganet, “these;”—masculine ![]() annat, feminine

annat, feminine ![]() annat (obl.

annat (obl. ![]() anniti) “those;”—masc.

anniti) “those;”—masc. ![]() ellut, “goods,” fem.

ellut, “goods,” fem. ![]() ellit, “goddesses,” &c. &c.

ellit, “goddesses,” &c. &c.

page lxxxvii note 1 If it were possible to obtain for the letter ![]() the secondary power of ka, I should of course prefer reading this word as yatkamma, and deriving it from

the secondary power of ka, I should of course prefer reading this word as yatkamma, and deriving it from ![]() but I have met with no other authority for such a phonetic value, and I cannot venture to adopt it on a single example.

but I have met with no other authority for such a phonetic value, and I cannot venture to adopt it on a single example.

page xcii note 1 The phrase to which I allude is ![]() the first word being often written phonetically, as

the first word being often written phonetically, as ![]() or

or ![]() dikta or dikut and thus admitting of explanation either as a correspondent for the Chaldee

dikta or dikut and thus admitting of explanation either as a correspondent for the Chaldee ![]() “a palm-tree,” or as a kindred derivative with

“a palm-tree,” or as a kindred derivative with ![]() “a wall,” or “tower.” The latter is, I think, however, the most probable explanation, for it is impossible to suppose that all the cities to which this phrase refers had either “ships” to be destroyed, or “palm-trees” to be cut down; whereas, there were undoubtedly “walls and towers” in every instance to be levelled by the Assyrian conqueror. I think, also, that

“a wall,” or “tower.” The latter is, I think, however, the most probable explanation, for it is impossible to suppose that all the cities to which this phrase refers had either “ships” to be destroyed, or “palm-trees” to be cut down; whereas, there were undoubtedly “walls and towers” in every instance to be levelled by the Assyrian conqueror. I think, also, that ![]() and

and ![]() must be plural formas, the theme being dika, which would nearly resemble

must be plural formas, the theme being dika, which would nearly resemble ![]() .

.

page xciii note 1 This verb is constantly used in the Insc. of Assyria, with the sense of “withholding;” comp. ![]() mandattasun yaklu, “they withheld their tribute.”

mandattasun yaklu, “they withheld their tribute.” ![]()

![]() yaklu tamarku, “they withheld allegiance,” &c. &c.

yaklu tamarku, “they withheld allegiance,” &c. &c.

page xciii note 2 Possibly the initial sign of this name, ![]() which is properly bar, may here have the secondary power of hi or hid, answering to the first syllable of the Hebrew title

which is properly bar, may here have the secondary power of hi or hid, answering to the first syllable of the Hebrew title ![]() . In Assyrian, at any rate, it often interchanges phonetically with

. In Assyrian, at any rate, it often interchanges phonetically with ![]() before t; compare Khursabad, 38, 65 and 16, 113, &c. The second sign

before t; compare Khursabad, 38, 65 and 16, 113, &c. The second sign ![]() has several values, but tik is that most usually employed, and that the last character

has several values, but tik is that most usually employed, and that the last character ![]() or

or ![]() of which paru seems to be the normal power, may also be pronounced gar, I infer from the forms

of which paru seems to be the normal power, may also be pronounced gar, I infer from the forms ![]() and

and ![]() aggur and attagar, which are the Kal and Nithpael(?) futures of the same root, answering to the Hebrew

aggur and attagar, which are the Kal and Nithpael(?) futures of the same root, answering to the Hebrew ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

page xciii note 3 I should wish to read ![]() as khalkhal, or supposing the word to be a plural form, as khali; and would thus compare with the title, the name of the river Halys, together with the geographical appellations of Calah, Calachene, Calneh, &c.; but this is, after all, little more than a conjecture; for the evidence which would attach to the letter

as khalkhal, or supposing the word to be a plural form, as khali; and would thus compare with the title, the name of the river Halys, together with the geographical appellations of Calah, Calachene, Calneh, &c.; but this is, after all, little more than a conjecture; for the evidence which would attach to the letter ![]() the power of khal, is exceedingly slight.

the power of khal, is exceedingly slight.

page xciv note 1 It may be convenient, also, to mention in this place, that I have at length decided in referring to the same root, ![]() the terms

the terms ![]() and

and ![]() which occur so often in the trilingual Inscriptions, and which have hitherto resisted all explanation. I am satisfied, indeed, from comparing Bel. Cyl., side 2, 1. 6; with East India Insc, Col. 6, 1. 26, that the letter

which occur so often in the trilingual Inscriptions, and which have hitherto resisted all explanation. I am satisfied, indeed, from comparing Bel. Cyl., side 2, 1. 6; with East India Insc, Col. 6, 1. 26, that the letter ![]() which is usually bul, has also the power of mal, and in the same way, therefore, that

which is usually bul, has also the power of mal, and in the same way, therefore, that ![]() mala aś bit, answers to vithápatiya, so will

mala aś bit, answers to vithápatiya, so will ![]() diyaku va mallu, answer to uzatayapatiya, the signification being “slain one and all.” The phrase, also,

diyaku va mallu, answer to uzatayapatiya, the signification being “slain one and all.” The phrase, also, ![]() mallut vassabbit, which occurs everywhere at Behistun, in the numerical notice of the slain and prisoners, must be rendered, “I took many prisoners,” or “I took prisoners numbering – — — —;” mallut being the masculine plural of an adjective derived from

mallut vassabbit, which occurs everywhere at Behistun, in the numerical notice of the slain and prisoners, must be rendered, “I took many prisoners,” or “I took prisoners numbering – — — —;” mallut being the masculine plural of an adjective derived from ![]() compare

compare ![]() Gen. xlviii. 19;

Gen. xlviii. 19; ![]() “in full number.” Nahum. i. 10, &c.

“in full number.” Nahum. i. 10, &c.

page xcv note 1 If we could suppose, however, that a root dik existed in Babylonian, of cognate rigin with the Sanscrit ![]() and having the same meaning, we should resolve most of the difficulties connected with the Cuneiforn

and having the same meaning, we should resolve most of the difficulties connected with the Cuneiforn ![]() and

and ![]() Dikta, as a feminine noun, would signify “the sharp,” or “the rapid,” and might thus be appropriately used as a name for the river Tigris; while dikat or dikut (plural forms) would also designate “boats” or “canoes,” from the rapidity of their movement, precisely as we have in Persian the cognate forms of

Dikta, as a feminine noun, would signify “the sharp,” or “the rapid,” and might thus be appropriately used as a name for the river Tigris; while dikat or dikut (plural forms) would also designate “boats” or “canoes,” from the rapidity of their movement, precisely as we have in Persian the cognate forms of ![]() “sharp” or “rapid,” and

“sharp” or “rapid,” and ![]() “a boat” or “canoe,” and in the same way as the skiffs used at the present day upon the Tigris and Euphrates, are named tarádeh, to indicate their lightness and velocity.

“a boat” or “canoe,” and in the same way as the skiffs used at the present day upon the Tigris and Euphrates, are named tarádeh, to indicate their lightness and velocity.

page xcvii note 1 That the letter ![]() must have represented a sound more nearly resembling i than a, is shown by its being always preceded by a consonant of the i class, when it is included with such a consonant in a single articulation.

must have represented a sound more nearly resembling i than a, is shown by its being always preceded by a consonant of the i class, when it is included with such a consonant in a single articulation.

page xcviii note 1 I may at any rate, however, cite the word ![]() vusalti, “fighting,” in a passage regarding the titles of Sargina, which is inscribed on the reverse of the Khursabad Slabs:—

vusalti, “fighting,” in a passage regarding the titles of Sargina, which is inscribed on the reverse of the Khursabad Slabs:—

I should propose to render tliis in English by “The king, who throughout his reign his enemies never spared; [who] in war and battle never ceased fighting; who smote the great ones of the earth like [briars, (?)]” &c.

page c note * As this sheet of the Analysis is passing through the press, I think I have discovered that the sign ![]() has the power of khas, as well as of ku, and this discovery has led to the identification of

has the power of khas, as well as of ku, and this discovery has led to the identification of ![]() or hvakhas, as a participial noun derived from

or hvakhas, as a participial noun derived from ![]() “to do,” and immediately cognate with

“to do,” and immediately cognate with ![]() which, indeed, exactly answers both in sense and etymology to the Persian kara. The equivalent of the Babylonian kh with the Hebrew y, is proved by a multitude of examples.

which, indeed, exactly answers both in sense and etymology to the Persian kara. The equivalent of the Babylonian kh with the Hebrew y, is proved by a multitude of examples.

page c note 1 In many cases, the power of lik answers sufficiently well for ![]() compare the orthography of

compare the orthography of ![]() Khilikku, for Cilicia, and the constant unicn of

Khilikku, for Cilicia, and the constant unicn of ![]() with a succeeding k; but I do not consider the value to be by any means established. The Hieratic form, however, of this letter is, I think,

with a succeeding k; but I do not consider the value to be by any means established. The Hieratic form, however, of this letter is, I think, ![]() and that sign lias certainly the phonetic power of lik or luk.

and that sign lias certainly the phonetic power of lik or luk.

page cii note 1 It certainly appears to me as if the term ![]() without being a geographical title, was still expressly employed to denote the valley of the Euphrates, or perhaps the Mesopotamian plains. In almost all cases where the king of Assyria takes the title of king of

without being a geographical title, was still expressly employed to denote the valley of the Euphrates, or perhaps the Mesopotamian plains. In almost all cases where the king of Assyria takes the title of king of ![]() that epithet supersedes the title of king of Babylon. (Compare British Museum, 12. 4; 19. 6, 17. 1; 33. 1; Obelisk, side 1, 1. 16.) In the Khursabad Inscriptions again, the epithets “

that epithet supersedes the title of king of Babylon. (Compare British Museum, 12. 4; 19. 6, 17. 1; 33. 1; Obelisk, side 1, 1. 16.) In the Khursabad Inscriptions again, the epithets “![]() ” and “

” and “![]() of Babylon” are always associated (see everywhere in commencement of Inscriptions of Sargina), and in the same way the

of Babylon” are always associated (see everywhere in commencement of Inscriptions of Sargina), and in the same way the ![]() are joined with the

are joined with the ![]() of Babylon and Borsippa in Khurs. 152. 2. The application of the term, however, seems more general in the epithet taken by the Nimrud king. British Museum, 1. 1. 2.

of Babylon and Borsippa in Khurs. 152. 2. The application of the term, however, seems more general in the epithet taken by the Nimrud king. British Museum, 1. 1. 2.

a phrase which I doubtfully translate by “the strong ruler who, walking in the service of Assar, his lord, overcame innumerable kings of the foreign countries” oi perhaps “of the plains of Mesopotamia.” It should also be observed, that this term ![]() is rendered in the East India Inscription, col. 10, 1. 9, by

is rendered in the East India Inscription, col. 10, 1. 9, by ![]() and on Bel. Cyl., side 3, 1.51, by

and on Bel. Cyl., side 3, 1.51, by ![]() , as if the sign

, as if the sign ![]() had the phonetic value of kip, kiprát being the masc. plur. and kiprat the fern. sing, of an adjective, signifying “great,” and allied to the root which is

had the phonetic value of kip, kiprát being the masc. plur. and kiprat the fern. sing, of an adjective, signifying “great,” and allied to the root which is ![]() in Hebrew, and

in Hebrew, and ![]() in Arabic. The signification, too, of “the great river” (the

in Arabic. The signification, too, of “the great river” (the ![]() of Gen. xv.18), would apply perfectly to the Euphrates, but it would be difficult to account for the employment of kiprát, so explained in other passages, unless we supposed the title to have been used with an express reference to the river, geographically, rather than in its primitive and indefinite sense of “great.”

of Gen. xv.18), would apply perfectly to the Euphrates, but it would be difficult to account for the employment of kiprát, so explained in other passages, unless we supposed the title to have been used with an express reference to the river, geographically, rather than in its primitive and indefinite sense of “great.”