No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2011

page 97 note 1 July, 1926, pp. 433–6.

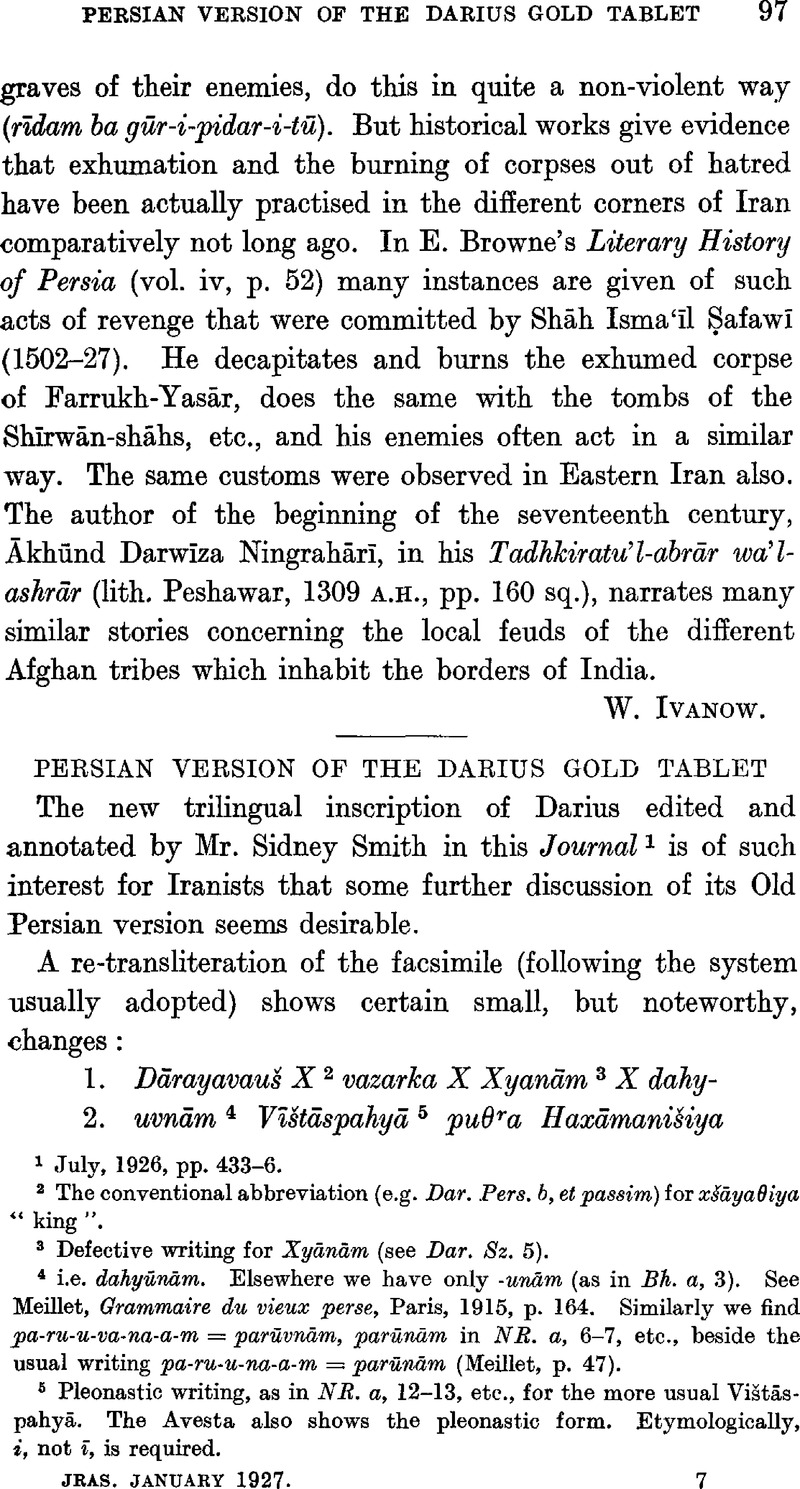

page 97 note 2 The conventional abbreviation (e.g. Dar. Pers. b, et passim) for xšāyaθiya “king”.

page 97 note 3 Defective writing for Xyānām (see Dar. Sz. 5).

page 97 note 4 i.e. dahyūnām. Elsewhere we have only -unām (as in Bh. a, 3). See Meillet, , Grammaire du vieux perse, Paris, 1915, p. 164Google Scholar. Similarly we find pa-ru-u-va-na-a-m = parūvnām, parūnāmin NS. a, 6–7, etc., beside the usual writing pa-ru-u-na-a-m = parūnām (Meillet, p. 47).

page 97 note 5 Pleonastic writing, as in NR. a, 12–13, etc., for the more usual Vištāspahyā. The Avesta also shows the pleonastic form. Etymologically, i, not ī, is required.

page 98 note 1 Written -mi-i-y.

page 98 note 2 Read thus (cf. e.g. martiyaibiš, Bh. i, 56–7), in conformity with the frequent use of Saka (Bh. k, 2; NR. a, 25, 25–6, 28; NR. xv; Dar. Pers. e, 18), rather than Sakibiš, which presupposes a base in -in, whose meaning (“possessing”) would be practically impossible to reconcile with the context.

page 98 note 3 Elsewhere written Suguda, Suguda (e.g. NR. a, 23). Cf., perhaps, the Avesta form Suγδa- and the Greek Σογδιáνη (cf. Meillet, p. 75).

page 98 note 4 For the reading āmata… ā rather than amata … ā see my remarks in the text under (3).

page 98 note 5 For the conventional reading Spardā (sa-pa-ra-da-a) see Meillet, pp. 26, 59.

page 98 note 6 Pleonastic writing as contrasted with υiθam in Bh. i, 69, 71 (cf. Meillet, p. 46). The Avesta likewise has vīs- beside vis-, the latter being etymologically correct (cf. Sanskrit víś-).

page 98 note 7 For alla “than” see Brockelmann, , Grundriss der vegleichenden Grammatik der semitīschen Sprachen, Berlin, 1908–1913, ii, 426–7Google Scholar.

page 99 note 1 Meillet, pp. 172, 189–90; Reichelt, , Awestisches Elementarbuch, Heidelberg, 1909, p. 276Google Scholar; Bartholomae, , Altiranisches Wörterbuch, Strasbourg, 1904, coll. 137, 1751–2Google Scholar; cf. also Brugmann, , Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogerrnanischen Sprachen, do., 1897–1916, II, ii, 894–6Google Scholar.

page 99 note 2 Cf. Meillet, pp. 187, 200; Reichelt, p. 275; Bartholomae, col. 852; on the word in general see Brugmann, II, ii, 884–7.

page 99 note 3 Die persischen Keilinschriflen, Leipzig, 1847, p. 59Google Scholar.

page 99 note 4 JRAS. 1847, pp. 294, 295, 297; 1849, pp. 189–90.

page 100 note 1 Cf. Meillet, p. 192; Reichelt, pp. 268–70; Bartholomae, coll. 300–303; Brugmann, II, ii, 818–19; Delbrück, , Allindische Syntax, Halle, 1888, pp. 451–3Google Scholar. Old Persian script has no way of distinguishing initial or single a from ā.

page 100 note 2 Cf. Brugmann, II, iii, 1008–9, and also his Griechische Grammatik, 4th ed., Munich, 1913, pp. 627–8Google Scholar; Delbrück, , Vergleichende Syntax der indogermanischen Sprachen, Strasbourg, 1893–1900, ii, 506–11Google Scholar.

page 100 note 3 On adverbial formations in -*te generally see Brugmann, II, ii, 731–2.

page 100 note 4 For this shortening (or, rather, restoration of an original short vowel) see Meillet, pp. 79, 80, 166, 174.

page 101 note 1 Meillet, p. 173; Brugmann, II, ii, 115, 166–7, 670, 730–1; Lindsay, , The Latin Language, Oxford, 1894, pp. 561–2Google Scholar.

page 101 note 2 For this pronoun see Brugmann, , Die Demonstrativpronomina in den indogermanischen Sprachen, Leipzig, 1904, p. 111Google Scholar.

page 101 note 3 Explanation of amata as from *ahmatah, *asmatas is impossible, since the correlative of this pronominal base is given by Sanskrit átas (cf. Sanskrit tátas: tasmāt; yátas: yasmāt; etc.).