No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

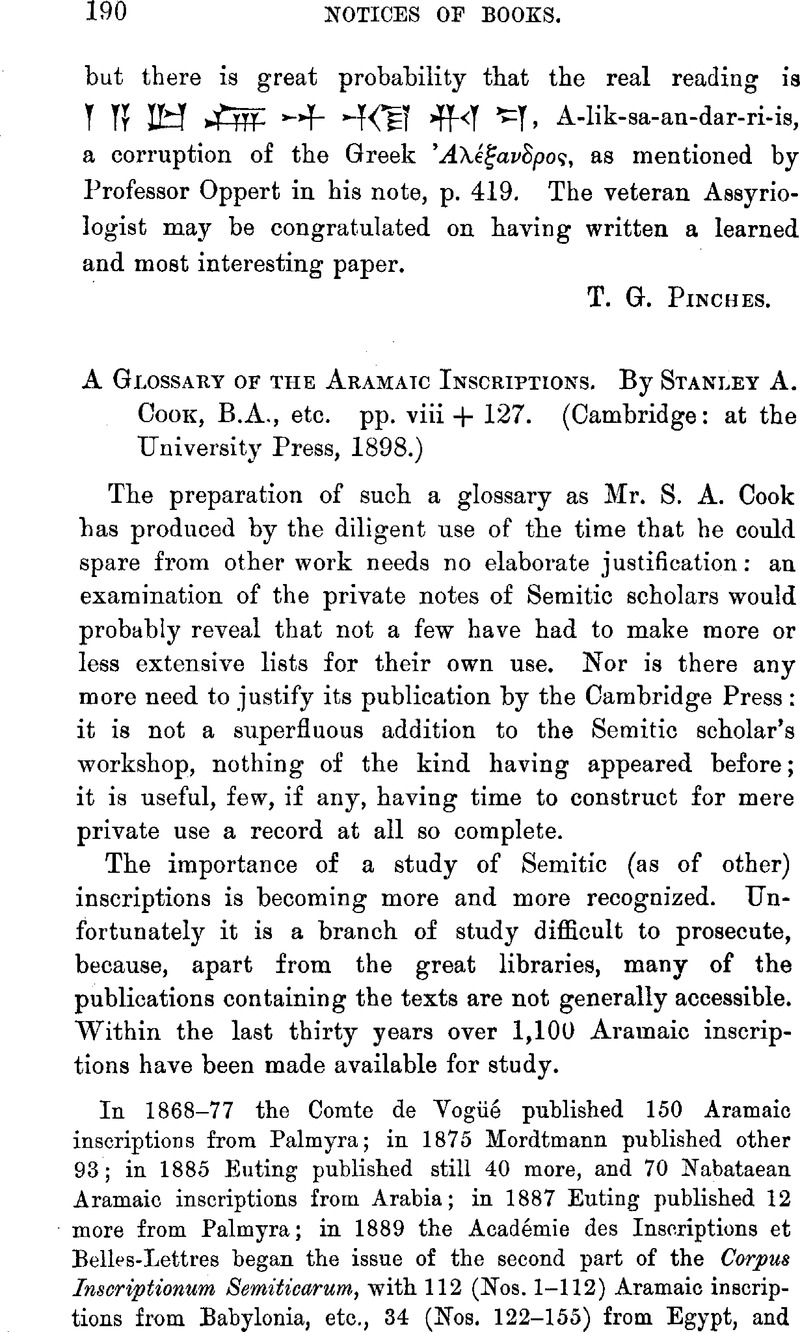

A Glossary of the Aramaic Inscriptions. By Stanley A. CookB.A., etc. pp. viii + 127. (Cambridge: at the University Press, 1898.)

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notices of Books

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Asiatic Society 1899

References

page 191 note 1 We think that readers who at first object to the very free use of abbreviations and symbols will in time come to appreciate them. We do not like, however, the hybrid ‘cfs.’; it should be cps. or cft. (if Pehlevi has to be learned it does not need to be copied). Certain readers would find it convenient to be told that the frequent references to Ibn Doreid are to the Kitāb el-Ištiḳāḳ, ed. Wüstenfeld. A symbol indicating the origin of the inscriptions cited merely by numbers would have been useful. In the article ![]() , e.g., printing 158N for 168 would have informed the reader that 158, as well as N7, is a Nabataean inscription.

, e.g., printing 158N for 168 would have informed the reader that 158, as well as N7, is a Nabataean inscription.

page 192 note 1 Occasional slight discrepancies between a note of reference and the place referred to (e.g. ![]() on p. 11, third article, compared with

on p. 11, third article, compared with ![]() on p. 52) are almost unavoidable and will mislead no one.

on p. 52) are almost unavoidable and will mislead no one.

page 193 note 1 On p. 42, however, under ![]() , 1204 should be 124; and on p. 63, under

, 1204 should be 124; and on p. 63, under ![]() , 362 should be 662. Moreover,

, 362 should be 662. Moreover, ![]() in

in ![]() and in

and in ![]() , on pp. 22 and 97, should be

, on pp. 22 and 97, should be ![]() . The facsimile is quite unambiguous.

. The facsimile is quite unambiguous.

page 193 note 2 It is not worth while pointing out such things as omissions or misplacements of ![]() ; but it may be of use to some readers to correct the following misprints:— on p. 13

; but it may be of use to some readers to correct the following misprints:— on p. 13 ![]() for the

for the ![]() of CIS—i.e.

of CIS—i.e. ![]() ; on p. 19

; on p. 19 ![]() for

for ![]() of Euting; on p. 27

of Euting; on p. 27 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 37

; on p. 37 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 43

; on p. 43 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 53

; on p. 53 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 55

; on p. 55 ![]() (following a misprint in De Vogüé) for

(following a misprint in De Vogüé) for ![]() , and

, and ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 88 'Obaišat (after CIS) for 'Obaisat; on p. 93

; on p. 88 'Obaišat (after CIS) for 'Obaisat; on p. 93 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 96

; on p. 96 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 97

; on p. 97 ![]() for

for ![]() ; on p. 111

; on p. 111 ![]() for

for ![]() ; (on p. 113

; (on p. 113 ![]() is a rare form, not an error for

is a rare form, not an error for ![]() ;) on p. 115

;) on p. 115 ![]() for

for ![]() ; and on p. 119

; and on p. 119 ![]() for

for ![]() , and

, and ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

page 193 note 3 Sometimes, however, the effort to be concise leads to obscurity or misstatement: on p. 19, under ![]() , Nüldeke's explanation “one who is cut from the body of his mother” is not an alternative translation of

, Nüldeke's explanation “one who is cut from the body of his mother” is not an alternative translation of ![]() , but a translation of

, but a translation of ![]() ; in the same article Leps. 86 refers to Denkmäler aus Aegypten, Abth. vi (Band xi), Tafel 14–21; on p. 22 ānif and ‘nose’ are alternatives, not equivalents; on p. 56 the juxtaposition of

; in the same article Leps. 86 refers to Denkmäler aus Aegypten, Abth. vi (Band xi), Tafel 14–21; on p. 22 ānif and ‘nose’ are alternatives, not equivalents; on p. 56 the juxtaposition of ![]() and Heb.

and Heb. ![]() suggests to the unwary reader that the Arabic word is known in the sense of ‘grasshopper’; on p. 105, if ‘to place, to set’ be correct,

suggests to the unwary reader that the Arabic word is known in the sense of ‘grasshopper’; on p. 105, if ‘to place, to set’ be correct, ![]() should be

should be ![]() . On the other hand, there seems to be a misapprehension on p. 38 in the article

. On the other hand, there seems to be a misapprehension on p. 38 in the article ![]() .

. ![]() does not mean ‘tanner.’ Mordtmann means to say that the Palmyrene proper name

does not mean ‘tanner.’ Mordtmann means to say that the Palmyrene proper name ![]() , coming from a root = Arab.

, coming from a root = Arab. ![]() , will mean ‘tanner.’ Gĕrăm on p. 37, given as the Ethiopic for ‘fear,’ should be germā. On p. 75

, will mean ‘tanner.’ Gĕrăm on p. 37, given as the Ethiopic for ‘fear,’ should be germā. On p. 75 ![]() , Manawāt, should be

, Manawāt, should be ![]() , Manāt.

, Manāt.

In the case of Assyrian and Egyptian words, it is to be regretted that the system of transliteration employed in the CIS has been preserved. It is extremely desirable that, whatever be done about the Egyptian vowels, the system of transliteration of the consonants that is now dominant should be used in all Semitic work. This does not in Assyrian, as in Arabic, employ a ḥ and a ḫ but only a ḫ—![]() not being distinguishable, except etymologically. In any case it is misleading to find kimaḥḥi on p. 37, and similarly ḥ in almost all Assyrian words, but patâḫu on p. 24. In Egyptian, on the contrary, it need hardly be said, ḥ and ḫ represent distinet symbols and distinet sounds. Thus, in ḥakonu(i) on p. 53, and in Ḥor en ḥeb on p. 56, ḥ is correct; but if so, in ḥrd ḥrt on p. 56, in anḥ (i.e. 'nḫ) on p. 94, in ḥontu on p. 82, in ḥalis on p. 50 (and of course in

not being distinguishable, except etymologically. In any case it is misleading to find kimaḥḥi on p. 37, and similarly ḥ in almost all Assyrian words, but patâḫu on p. 24. In Egyptian, on the contrary, it need hardly be said, ḥ and ḫ represent distinet symbols and distinet sounds. Thus, in ḥakonu(i) on p. 53, and in Ḥor en ḥeb on p. 56, ḥ is correct; but if so, in ḥrd ḥrt on p. 56, in anḥ (i.e. 'nḫ) on p. 94, in ḥontu on p. 82, in ḥalis on p. 50 (and of course in ![]() and

and ![]() ), in ḥonsu on p. 55, and in other examples, ḥ should be ḫ. We may add here that we do not suppose the author means to propose a new theory of the date of Daniel when he assigns it to the middle of the second century b.c. (p. 3, note 2).

), in ḥonsu on p. 55, and in other examples, ḥ should be ḫ. We may add here that we do not suppose the author means to propose a new theory of the date of Daniel when he assigns it to the middle of the second century b.c. (p. 3, note 2).