Article contents

Art. IX.—On the Muhammedan Science of Tâbír, or Interpretation of Dreams

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2011

Extract

The subject of Dreams has invited the inquiry of science in many ages and countries. A phenomenon of such frequent occurrence in connection with one of the ordinary functions of the animal economy could not fail to interest men of all classes and temperaments. To develop its theory as a mechanical working of the brain in sleep, or a secret energy of the mind during the temporary inaction of the bodily powers, equally forms a part of physics and of metaphysics; but, further than this, the association of dreams with objects and events having no immediate affinity with the waking thoughts, pursuits, or interests of the dreamer, thus seeming to indicate a sense of things to come, has led inquirers, with more or less of superstitious belief, to rely upon this as a species of foreknowledge within the reach of all, even of ungifted persons. Mankind, naturally anxious for direction in their worldly undertakings beyond the limits of human wisdom, studied every mode of possessing that information which might be supposed attainable by mysterious agency, and, in addition to the less permissible means of sorcery and divination, have endeavoured to obtain the desired instruction from observation of their sleeping thoughts, and even to reduce this process to a system.

- Type

- Original Communications

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Asiatic Society 1856

References

page 119 note 1 The saying, in full, is thus:—![]()

![]() “Dreams constitute one of the forty-six portions of the prophetic mission.” Muhammed was forty years old when he first received inspiration, between which time and the age of sixty-three, when he died, were twenty-three years; during this interval, whatever he desired was communicated to him in dreams. This is the explanation given of the saying, though the double of twenty-three, forty-six, is expressed in the text. Probably from this difficulty, it appears, when quoted, in many forms, and seldom correctly, as 20, 40, and more frequently 23. In the Mishkát it is curtailed to “Good dreams are one of the parts of prophecy” (from Anas).

“Dreams constitute one of the forty-six portions of the prophetic mission.” Muhammed was forty years old when he first received inspiration, between which time and the age of sixty-three, when he died, were twenty-three years; during this interval, whatever he desired was communicated to him in dreams. This is the explanation given of the saying, though the double of twenty-three, forty-six, is expressed in the text. Probably from this difficulty, it appears, when quoted, in many forms, and seldom correctly, as 20, 40, and more frequently 23. In the Mishkát it is curtailed to “Good dreams are one of the parts of prophecy” (from Anas).

It is to be observed, that the chapters relating to dreams in that collection of tradition are extremely scanty and unsatisfactory, the greater part being taken up in the relation of one single dream of Muhammed's, and his own sayings on the subject being few and unimportant. This is the more to be regretted, as those which are found in the native works on Tâbír, especially of Persian writers, are never to be depended on for accuracy; in the present quotation, for example, ![]() sometimes is written

sometimes is written ![]() and

and ![]() “a portion of Sunnah;” leaving the number, forty, quite incapable of being explained.

“a portion of Sunnah;” leaving the number, forty, quite incapable of being explained.

In the Netáïj, as quoted in the Eneycloptæische Uebersicht, a much more exact explanation is given of the tradition; viz. that the forty-sixth part of prophɛcy means the first six months of Muhammed's inspiration, in which he received Divine communications through dreams, previously to the more open revelations made to him in the person of the angel Gabriel; these six months being the forty sixth part of the twenty-three years of Muhammed's mission as above. The explanation I have quoted is from the Kámil ul Rúyá.

page 120 note 1 Ch. xii.

page 120 note 2 Cur. ch. xlviii. 27.

page 120 note 3 In the translation published at Calcutta by Captain Matthews, Vol. II., in which chapter iv. of the 22nd book treats of traditions on dreams.

page 121 note 1 The dream is alluded to in the life of this Khalif in Hammer-Purgstall's Gemäldesaal, Vol. I., p. 289.

page 121 note 2 Similar announcements were made by dreams to Actia, the mother of Augustus; Arlotta, the mother of William of Normandy; of the birth of Cyrus; and in more modern history, those of, Scanderbeg and of St. Bernard.

page 122 note 1 In the encyclopediao arrangement of Muhammedan sciences, Tâbír, Dreaminterpretation, is classed with Medicine. The technical terms are few, and are so simple as to obtain their explanation as they occur. Tâbír ![]() from which the science is called, is Interpretation of Dreams, from

from which the science is called, is Interpretation of Dreams, from ![]() from which root also Ibárat

from which root also Ibárat ![]() of similar signification, and Muâbbir

of similar signification, and Muâbbir ![]() an interpreter of dreams, or dream-expounder; words for which we have no specific terms in English, as, in German, Traumauslegung, Traumausleger, Traumauslegungskunst; and in Greek, Oneirokrites, Oneiromanteia, &c. Tâwíl,

an interpreter of dreams, or dream-expounder; words for which we have no specific terms in English, as, in German, Traumauslegung, Traumausleger, Traumauslegungskunst; and in Greek, Oneirokrites, Oneiromanteia, &c. Tâwíl, ![]() equivalent to Tâbír, is also Dream-interpretation, and in some places is used for its fulfilment or verification by the occurrence of the event predicted in it. Ahkám, Ahlám, Azghás, &c., the various kinds of dreams, are explained in their places. The most general term, in Persian, is Kh'âb

equivalent to Tâbír, is also Dream-interpretation, and in some places is used for its fulfilment or verification by the occurrence of the event predicted in it. Ahkám, Ahlám, Azghás, &c., the various kinds of dreams, are explained in their places. The most general term, in Persian, is Kh'âb ![]() signifying also sleep; and, in Arabic, Rúya

signifying also sleep; and, in Arabic, Rúya ![]() Manám

Manám ![]() Wákiâh

Wákiâh ![]() used also

used also ![]() in Persian; also Mâámalah,

in Persian; also Mâámalah, ![]() of rare occurrence in this sense, but employed almost exclusively so in Tipú's Dream Book. It is remarkable that no verb in Persian or Arable specially signifies “to dream;”

of rare occurrence in this sense, but employed almost exclusively so in Tipú's Dream Book. It is remarkable that no verb in Persian or Arable specially signifies “to dream;” ![]() and

and ![]() to see in sleep, being used instead, similar to the Russian Vidéte vo sné. In Turkish

to see in sleep, being used instead, similar to the Russian Vidéte vo sné. In Turkish ![]() that which was seen (in sleep) and

that which was seen (in sleep) and ![]() a dream,

a dream, ![]() to dream, and

to dream, and ![]() to see in sleep, are the most usual expressions. Hindustani

to see in sleep, are the most usual expressions. Hindustani ![]() .

.

page 123 note 1 D'Herbelot observes on the subject of works on Tâbír, “II y en a m^me un qui porte le titre de Ossoul Daniel, comme si le Prophète Daniel en etoit l'auteur;” alluding, probably, to the vague notice in Haji Khalfah.

page 124 note 1 In the Class of Traditionists, Ueberlieferer, vol. ii. p. 129, no. 397; and again as Mystiker, p. 176.

page 124 note 2 Mentioned by Háji Khalfah. Nos. 3061–2–3–4–6 of Flügel's edition.

page 124 note 3 Of a long series of Greek writers on this subject, the most celebrated and by far the best is Artemidorus Daldiauus, of Daldis in Asia Minor, who lived in the time of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius. He is also the authority most frequently named by Arabian writers on Tâbír, and the resemblance of the two systems is the most strongly traced in his writings. An excellent notice of his Oneirocritica is given in the chapter on dreams, in a very interesting work by the Rev. H. Christmas, which bears the ingenious, though rather fanciful title of “The Cradle of the Twin Giants.” Apparently, the edition of Artemidorus consulted by the learned author was not accompanied by the so-called Greek and Latin version of Ibn Sírín's Oneirocritics, a comparison with which would, no doubt, not have escaped his attention.

page 126 note 1 In Mr. Lane's Modem Egyptians it is said, the authorities most popularly consulted by the Arabs of the present day are Ibn Sháhín and Ibn Sírín, who is there stated to have been a pupil of the former. It will be seen, however, that the dates of authorities quoted by Ibn Sháhín are incompatible with such a connection.

page 126 note 2 The Curán and Traditions notice several dreams connected with personages in Holy Writ, but not received by us. Thus, Pharaoh foresaw in a dream the destruction of his host in the Bed Sea, and in a dream Abraham was desired to sacrifice Isaac. Cor. xxxvii. 101, &c.

page 127 note 1 ![]()

page 127 note 2 These terms were applied to Pharaoh's dream, by his interpreters, to excuse their own inability to explain it Cur. xii. 44.

page 127 note 3 A special arrangement of the Divine Providence, according to Muhammedan belief, prevents much of the evil which might arise from such Satanic interference. “Iblís,” says Jábir Maghrabi, “though able to assume all other forms, is not permitted to appear in the semblance of the Deity, or of any of his angels or prophets, nor any of the higher order of created objects. There would otherwise be much danger to human salvation, as he might, under the appearance of one of the prophets, or of some superior being, make use of this power to seduce men to sin. To prevent this, whenever he attempts to assume such forms, fire comes down from heaven and repulses him.” Tradition says: “God has created the stars for three uses;—for ornament of the heavens; for man's guidance in deserts and by sea; and to stone the Devil with.” In two other traditions in the Mishkát Muhammed says that the Devil cannot assume his likeness to deceive in dreams.

page 127 note 4 ![]() Perhaps the λληγοπικοì of Artemidorus ?

Perhaps the λληγοπικοì of Artemidorus ?

page 127 note 5 This was Muhammad's own classification, according to a tradition of Masúd Ibn Abdallah.

page 128 note 1 “A dream cometh from the multitude of business.”—Ecclesiastes, ch. ii. v. 3.

page 128 note 2 Thus Nicephorus—

ψɛυδɛις ονɛιρυς κολιας δηςɛι γομος

Πολλη ποσις τɛ και καπωσις ακρατου

και φπωυτιδων ζοφωσις και φρɛνων γνοφος.

page 129 note 2 The 109th, 112th, 113th, and 114th Súrahs are also recommended.

page 130 note 1 The Greek system prescribes a similar preparation, in order to obtain auspicious and lucid dreams.

Аρχɛ προ παντων και παθων και κοιλιαζ

και δακρυα στɛυαξου υκ τωυ ομματωυ

Ευχασ προπɛμπωυ ɛξ ολης της καπδιας

και χɛιπας αιπωυ τω Θɛω και δɛσποτη

Οτɛ προς υπνον ως βποτος νɛυσαι θɛληζ

Niceph. Constant.

page 131 note 1 This seems rather at variance with the Muhammedan doctrine of predestination; but the evil is intended to be averted by prayer, &c.

page 132 note 1 Artemidorus states also the qualifications necessary for an interpreter of dreams, but they are not so rigidly exacted by his rules.

page 133 note 1 Similar duties are enjoined in the Greek system as explained by Artemidorus with respect to inquiring the name, age, habits, and occupation of the dreamer and his state of health.

page 134 note 1 Characteristic of that Khalif himself, who was particularly distinguished for charity and almsgiving, and would naturally attach great importance to such virtues.

page 134 note 2 Ibn Sírín says, dreamers are necessarily to be considered believers or infidela (Múmin or Káfir), and further, of one of these fourteen classes:—

page 134 note 3 Αιɛι τοις μικρις μικα διδωσι θɛοι. Callimachus.

page 135 note 1 Eating camel's flesh is forbidden in Leviticus, but not in the Curán.

page 135 note 2 ![]() Synonymous with Abí is Bihí, meaning also Prosperity.

Synonymous with Abí is Bihí, meaning also Prosperity.

page 136 note 1 A similar example is given in the pseudo-Ibn Sírín.

page 136 note 2 The influences are, of course, those of the planets, which are here called by their pagan names as more familiar, instead of Persian as in the original.

page 136 note 3 This inquiry was even practised by the ancient Arabians before Islamism.

page 137 note 1 This system is not easy to understand from the passage quoted, altbongh the examples in it perfectly correspond with their interpretation, severally, in classed dream-books. Some, however, are not to be found explained there. The other examples given in the texts will be added in an Appendix, to assist further investigation.

page 138 note 1 I cannot hut think that there is here also an allusion to the words Shutur and Ranj, forming, when combined, Shatranj, the name of Chess; Ranj, denoting the grief and pain from the accident, as Shutur does the name of the hospital, and resemblance of a broken leg to that of a camel, &c. It is true, in die Greek story, in which the game played is diee, this fancied connection no longer obtains. The Greek, indeed, is very probably the original story, as Dice would be converted, in a Muhammedan narrative, into Chess, a less objectionable game, or, at least, one on the lawfulness of which the opinions of the Orthodox are divided.

page 139 note 1 At the end of the 4th book of Artemidorna is a chapter on the period of fulfilment of dreams, chiefly depending on the time and season when the dream occurs, and very exactly arranged according to eaeh hour in succession; but it does not perfectly agree with the Eastern rules.

page 140 note 1 There is an Arabic proverb which says: “A, secret which reaches a third person, is lost.” ![]()

page 140 note 2 The passages quoted are the following:

9. “And there were nine men in the city, who acted corruptly in the earth, and behaved not with integrity.”—Cur. xxvii. 49.

8. “And others say they were seven [the Sleepers], and their dog was the eighth.”—xviii. 21.

7. “Seven fat kine, which seven lean kine devoured, and seven green ears of corn.”—xii. 43.

6. “Who hath created the heavens and the earth in six days, and then ascended his throne.”—x. 3.

5. (The authority is not given in either of the MSS.)

4. “And provided therein the food thereof, in four days [of the creation] equally, for those that ask.”—xli. 9.

3. “There is no private discourse among three persons, but He is the fourth of them.”—lviii. 7.

Also, “For three days [Zachariah's silence], otherwise than by gesture.”— iii. 36.

2. “The second of two [Abu Bekr], when they were both in the cave.”—ix. 40.

1. “Far be it from him. He is the sole, the Almighty God!”—xxxix. 6.

page 141 note 1 To feed from a golden vessel is, in some Tâbír Namehs, explained “to enjoy illicit pleasure.” Swine, in general, denote “bad men.”

page 142 note 1 The eastern houses having flat roofs and an open court in the middle, the easiest access, by stealth, would be in this way. In a story of the Anwári Suhaili, thieves enter a house by the roof, and are overheard consulting as to their descent into the court, in attempting which, one of them breaks his neck.

page 142 note 2 The circumstance of the coins bearing an effigy, which is unusual in Muhammedan coinage except in that of the Ortokides and a few others, seems to ndicate a Greek origin to this story.

page 143 note 1 1 Ch. ex. This chapter was delivered to Muhammed a short time only before his death, for which it was intended to prepare him.

page 145 note 1 A similar hypothesis is found in Bishop Newton's Treatise on Dreams, and in Baxter's Essay on the Phenomena of Dreaming.

page 146 note 1 The history of the manuscript is learned from the following note, written in the fly-leaf by Major Beatson, by whom the volume was presented to the Honourable East India Company from the Marquis Wellesley.

“ This register of the Sultaun's dreams was discovered by Colonel William Kirkpatrick, amongst other papers of a secret nature, in an escritoire found in the Palace of Seringapatam. Hubbeeb Oollah, one of the most confidential of the Sultaun's servants, was present at the time it was discovered. He knew that there was such a book of the Sultaun's composition, but had never seen it, as the Sultaun always manifested peculiar anxiety to conceal it from the view of any who happened to approach while he was either reading or writing in it. Of these extraordinary productions six only have been as yet translated, which I have inserted in the appendix of a View of the Origin and Conduct of the War. By some of them it appears that war and conquest, and the destruction of the Kaufers (Infidels) were no less the subjects of his sleeping than of his waking thoughts.

“ London, 23rd April, 1800. A. Beatson.”

page 148 note 1 The arrangement of the Sultan's cycle, and the other alterations made by Tipú in the calendar, are fully explained in Marsden's Numismata Orientalia, in describing the coins of that prince; and the system is also noticed in the Life of Tipú, translated by Colonel Miles for the Oriental Translation Fund.

page 148 note 2 Tipú reigned from the 20th December, 1782, to A.D. 1799, being killed on the 4th of May in that year.

page 149 note 1 The' Id ul Fitr, or Breaking the fast after Ramazan, commences with the appearance of the new moon, the first glimmering of which is watched for anxiously, and announced triumphantly by him who discovers it.

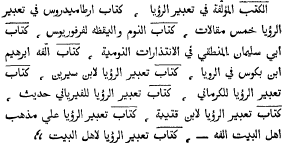

page 158 note 1 ![]() Fihristu 'I Kutúb, the oldest Atabic anthority for literatute, by Muhamroed ben Ishac al Nadím, is fully described in the last article of Hammer-Purgstall's Handschriften, No. 412, in whose collection there was at that time a copy of the first volume, unique in Western Europe. A transcript of the second volume has since been made from a MS. in one of the public libraries in Constantinople, and deposited in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. From this copy I am indebted to the kindness of my friend M. Garcin de Tassy for an extract Containing the subject of dreams, which, from the scarcity of the original, I insert here, verbatim, in text. It will be Been that, besides those, already quoted, of Ibn Sírín, Al Kirmání, and Ibn Cutaibah, and the Greek authors Artemidoras and Porphyrius, two other works are alluded to, under the general title of Tâbíru 'I Rúyá, but without their authors' names, and apparently designed for the use of the Shiahs.

Fihristu 'I Kutúb, the oldest Atabic anthority for literatute, by Muhamroed ben Ishac al Nadím, is fully described in the last article of Hammer-Purgstall's Handschriften, No. 412, in whose collection there was at that time a copy of the first volume, unique in Western Europe. A transcript of the second volume has since been made from a MS. in one of the public libraries in Constantinople, and deposited in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. From this copy I am indebted to the kindness of my friend M. Garcin de Tassy for an extract Containing the subject of dreams, which, from the scarcity of the original, I insert here, verbatim, in text. It will be Been that, besides those, already quoted, of Ibn Sírín, Al Kirmání, and Ibn Cutaibah, and the Greek authors Artemidoras and Porphyrius, two other works are alluded to, under the general title of Tâbíru 'I Rúyá, but without their authors' names, and apparently designed for the use of the Shiahs.

page 170 note 1 Artemideri Daldiani et Achmetis Sereimi F. Oneirocritica, Astrampsychi et Nicephori Versus etiam Oneirocritici. Nicolai Eigaltii ad Artemidorum Notæ. Lutetiæ, apud Marctlm Orry, via Jacobæa, ad insigne Leonis salientis.

- 7

- Cited by