Introduction

Increasing seawater temperatures related to climate change have become a major concern in recent years. High water temperatures have been predicted and confirmed to induce a shift in the distribution of marine organisms towards higher latitudes (Sunday et al., Reference Sunday, Bates and Dulvy2012; Poloczanska et al., Reference Poloczanska, Brown, Sydeman, Kiessling, Schoeman, Moore, Brander, Bruno, Buckley, Burrows, Duarte, Halpern, Holding, Kappel C, O'Connor, Pandolfi, Parmesan, Schwing, Thompson and Richardson2013; Hastings et al., Reference Hastings, Rutterford, Freer, Collins, Simpson and Genner2020). This distribution shift is also expected in sea turtles (Chaloupka et al., Reference Chaloupka, Kamezaki and Limpus2008; Patrício et al., Reference Patrício, Hawkes, Monsinjon, Godley and Fuentes2021; Mancino et al., Reference Mancino, Hochscheid and Maiorano2023). Green turtles (Chelonia mydas) are found worldwide in tropical to temperate waters (Suganuma, Reference Suganuma1994; Hirth, Reference Hirth1997). After leaving the nesting beaches in tropical and subtropical areas (Pritchard, Reference Pritchard, Lutz and Musick1997), hatchlings use the oceanic waters for several years (Musick and Limpus, Reference Musick, Limpus, Lutz and Musick1997). Juvenile turtles with straight and curved carapace lengths (SCL and CCL, respectively) of approximately 20–40 cm change their habitat from oceanic waters to neritic areas (Musick and Limpus, Reference Musick, Limpus, Lutz and Musick1997; Seminoff et al., Reference Seminoff, Allen, Balazs, Dutton, Eguchi, Haas, Hargrove, Jensen, Klemm, Lauritsen, MacPherson, Opay, Possardt, Pultz, Seney, Van Houtan and Waples2015). This ontogenic habitat shift was accompanied by a dietary shift from omnivory to herbivory (Reich et al., Reference Reich, Bjorndal and Bolten2007; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Boyle and Limpus2008; Jones and Seminoff, Reference Jones, Seminoff, Wyneken, Lohmann and Musick2013). Green turtles appear in coastal waters when their SCL reaches approximately 40 cm in the Northwest Pacific Ocean (Ishihara, Reference Ishihara and Kamezaki2012).

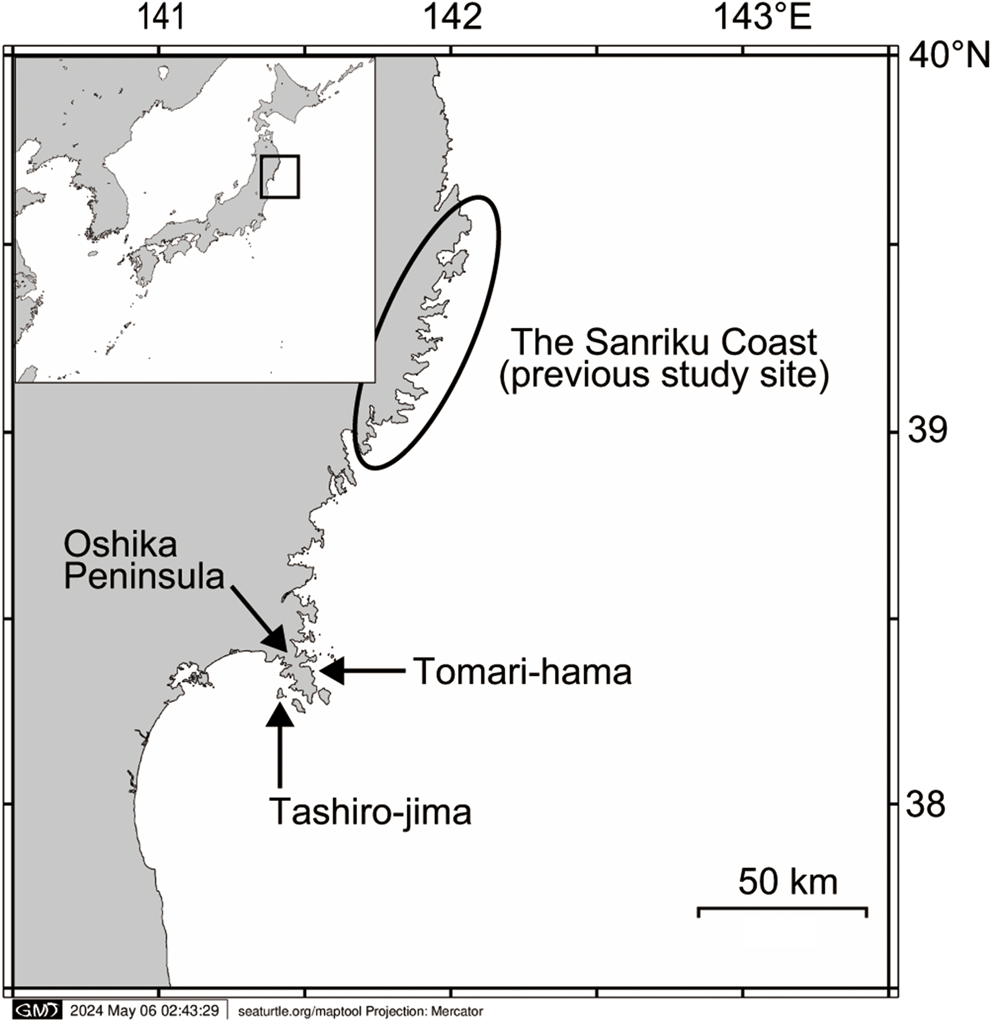

The Sanriku Coast (38°55′–39°40′ N, 141°40′–142°05′ E) is located on the Pacific coast of northeast Japan (Figure 1). This area is a relatively high-latitude habitat for green turtles in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. A bycatch survey, in which sea turtles incidentally caught in commercial fixed nets (one of the fishery methods: see Slack-Smith, Reference Slack-Smith2001) are brought to researchers, has been ongoing since 2005. The survey revealed that juvenile green turtles appear from July to November, peaking from late August to September (Fukuoka et al., Reference Fukuoka, Narazaki and Sato2015). According to mark-recapture studies and satellite tracking, these turtles conduct seasonal migrations of more than 500 km to reach their southern overwintering habitats (Fukuoka et al., Reference Fukuoka, Narazaki and Sato2015). No turtles have been captured in winter, indicating that the Sanriku Coast serves as a seasonal foraging habitat for this species.

Figure 1. Map of the study site.

The Oshika Peninsula, where the green turtles reported in this study were observed, is located approximately 100 km south of the previously surveyed area on the Sanriku Coast (Figure 1). A new monitoring survey at the Oshika Peninsula has been ongoing since 2017. Although systematic bycatch surveys like those along the Sanriku Coast (e.g. detailed morphometrically measuring, satellite tracking) have not been conducted, information on turtle bycatch has been collected. As a result, it was confirmed that green turtles were caught during late June and late November (personal communication, K. Fukuda). Additionally, sea surface temperature (SST) in this region drops to approximately 7°C during the winter months (February to April). This is below the threshold for cold stunning (<10°C: Milton and Lutz, Reference Milton, Lutz, Lutz, Musick and Wyneken2003) and the lethal temperature (<8°C: Witherington and Ehrhart, Reference Witherington and Ehrhart1989) for hard-shell sea turtles. The waters surrounding the Oshika Peninsula are, therefore, considered summer to autumn habitats for green turtles, similar to the Sanriku Coast. This study reports the appearance of green turtles during winter in the Oshika Peninsula. This is the first recorded observation of this species in winter on the Pacific coast of northeast Japan, which was previously considered a summer to autumn habitat.

Materials and methods

One individual found in the present study was incidentally observed by a diver during a single dive while conducting other research for benthic animals. Another individual was provided by a local fisherman who had cooperated with our bycatch surveys. The latter was measured morphometrically for SCL and body mass (BM). Species of the turtles were identified though diagnostic features including the number of vertebral and coastal scutes, the number of frontal scales, and the shapes of the carapace and head (Hirth, Reference Hirth1997). SST data at turtle observed points were obtained from fixed-point observation buoy via the website of the Miyagi Prefecture Fisheries Technology Institute (https://suisan-navi.pref.miyagi.jp/).

Results

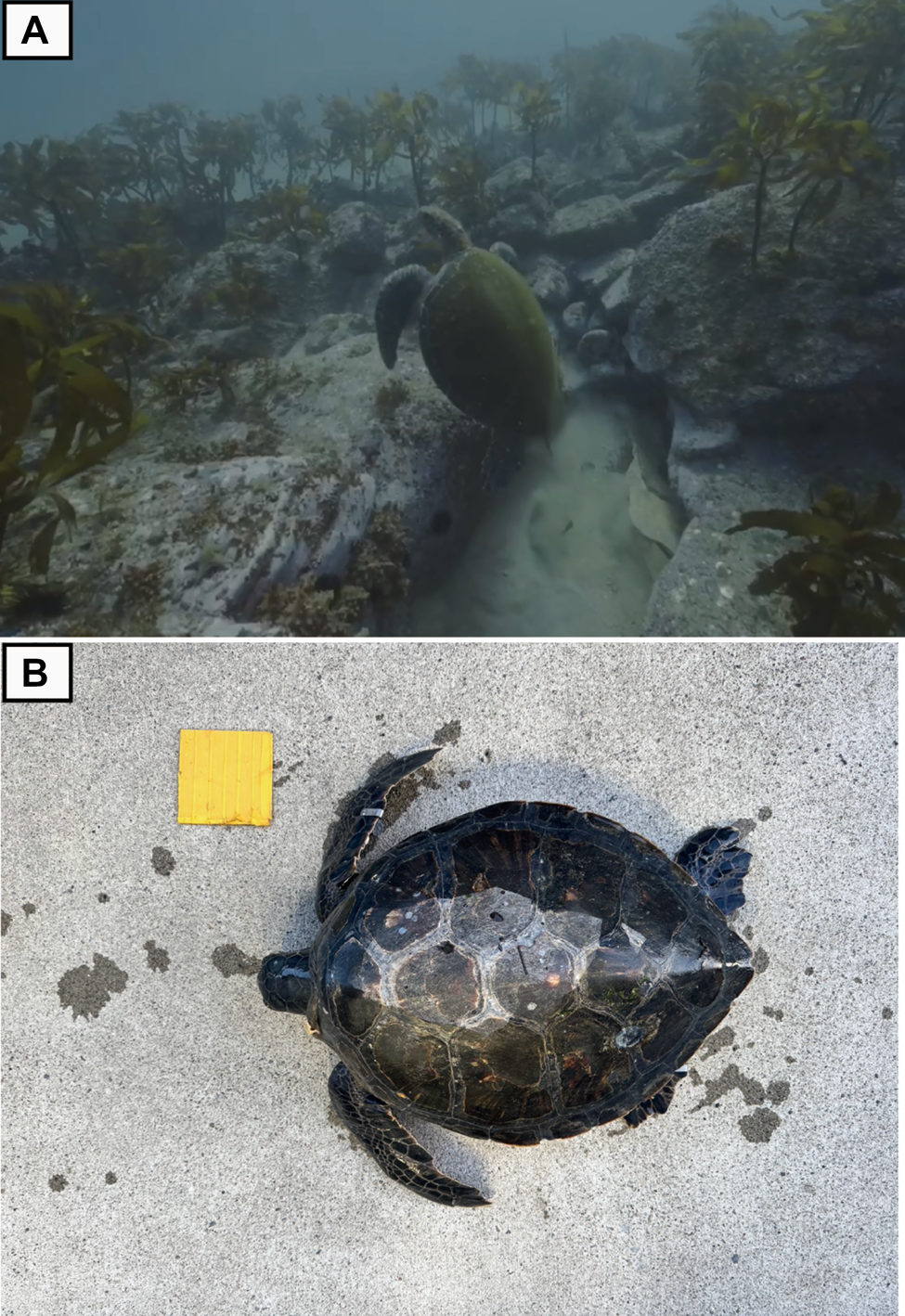

One turtle was observed at Tomari-hama on the Oshika Peninsula (38°21′ N, 141°31′ E) on 28 December 2023 (Figures 1, 2A, Table 1). This turtle was identified as Chelonia mydas based on the circle-shaped carapace and relatively small head (Figure 2A). The SST at Enoshima, the nearest observation point (7 km northeast of Tomari-hama), was 15.9°C. In addition, the turtle was observed to be actively swimming (Supplementary Movie S1) and demonstrated no signs of emaciation.

Figure 2. Green turtle (A) observed at Tomari-hama on 28 December 2023, and (B) incidentally captured in Tashiro-jima on 18 April 2024.

Table 1. Information on observed green turtles at Oshika Peninsula

SCL, Straight carapace length; BM, Body mass; SST, Sea surface temperature.

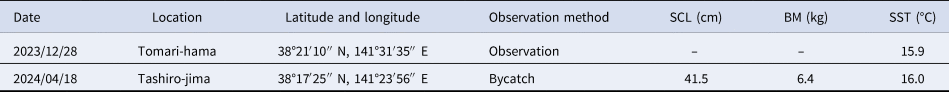

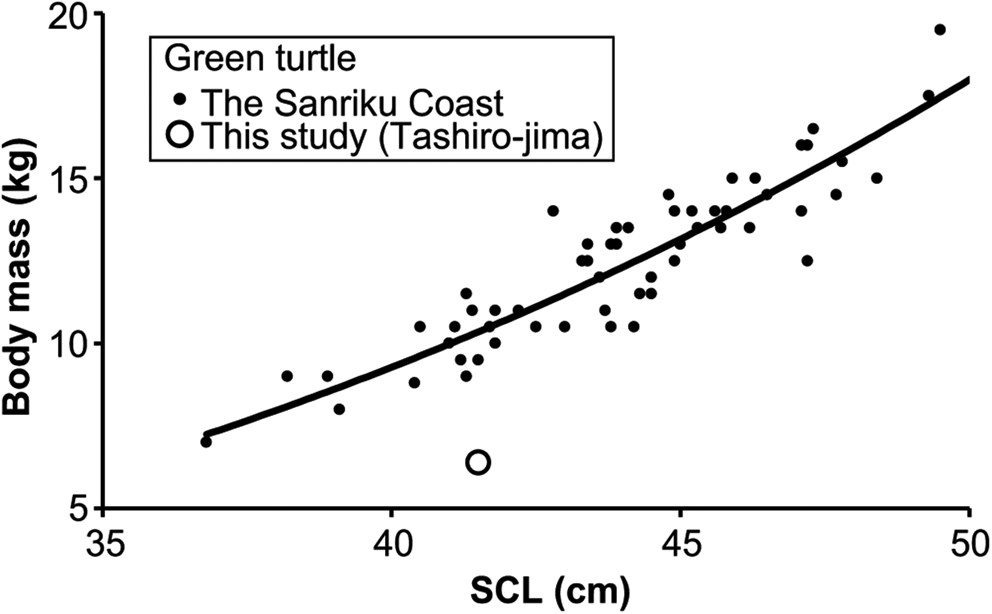

Additionally, another turtle was incidentally captured in a fixed net near Tashiro-jima on the Oshika Peninsula (38°17′ N, 141°24′ E) on 18 April 2024 (Figures 1, 2B). This turtle was identified as Chelonia mydas based on the presence of five central scutes, four pairs of lateral scutes, and one pair of prefrontal scale (Figure 2B). The SCL and BM of this turtle were 41.5 cm and 6.4 kg, respectively, indicating that this turtle is juvenile (Table 1). The BM of this turtle was lighter than the previous record for green turtles with a similar SCL on the Sanriku Coast (Figure 3), suggesting poor nutritional condition, but the turtle appeared to have sufficient energy left to swim. The SST at the time was 16.0°C. This turtle was released near the fixed net in which bycatch event occurred the following day after attaching Inconel tags for individual identification.

Figure 3. Relationship between straight carapace length (SCL) and body mass (BM). An open circle demonstrates the turtle in this study. The small filled circles indicate the turtles on the Sanriku Coast, and the regression curve is the relationship between SCL and BM (body mass = 1.64 × 10−4 × SCL2.97: Fukuoka et al., Reference Fukuoka, Narazaki and Sato2015).

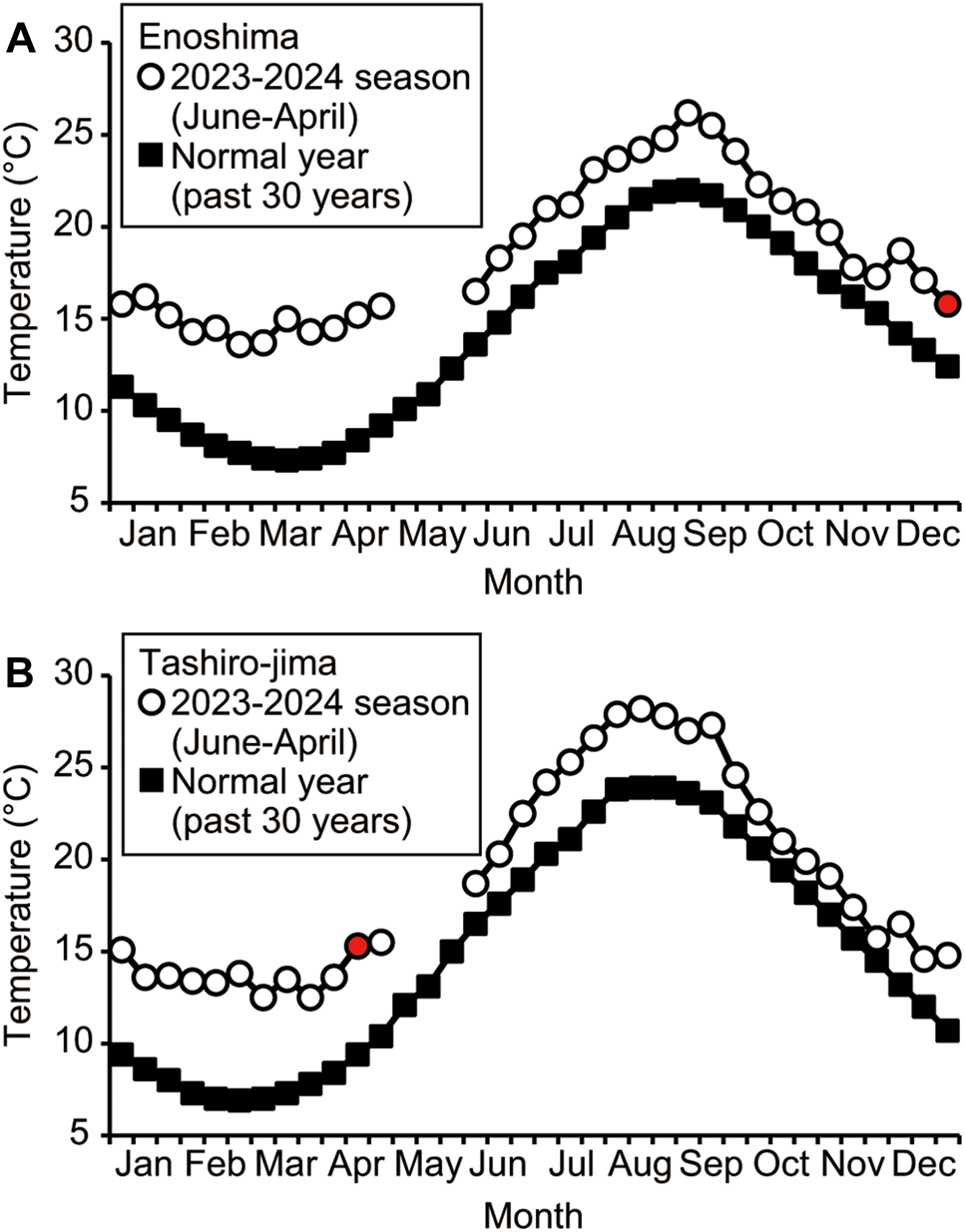

Seasonal changes in SST around the Oshika Peninsula are presented in Figure 4. The SST in late December (Enoshima) and mid-April (Tashiro-jima) is 12.4 and 9.4°C, respectively, in normal years (average on past 30 years). Hence, the SSTs at the time of the turtle observations in this study were 3.5 and 6.6°C higher than normal. These higher SSTs were additionally demonstrated over a wide range (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4. Seasonal changes of SST at (A) Enoshima and (B) Tashiro-jima. Filled squares and open circles indicate the normal year (past 30 years) and the current season, respectively. The red circle indicates the time when green turtles appeared in this study.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report of green turtles observed in winter on the Pacific coast of northeast Japan (> 38° N). Previous records of the earliest and the latest appearances of green turtles on the Oshika Peninsula noted the occurrence in late June and late November, respectively. The occurrences reported in this study were, therefore, two months earlier and one month later. However, the SSTs at the time of turtle observations (15.9 and 16.0°C) are close to the lower limit of the range at which green turtles have been captured on the Sanriku Coast (16–24°C, Fukuoka et al., Reference Fukuoka, Narazaki and Sato2015). The turtle observations in this study, therefore, did not indicate extremely low water temperature conditions. Moreover, the SST remained warmer than normal throughout the winter season (>12°C) and never dropped below the threshold for cold stunning in sea turtles (<10°C: Milton and Lutz, Reference Milton, Lutz, Lutz, Musick and Wyneken2003). It is, therefore, possible that the turtles observed in winter were not only transported by currents from the south but also overwintered around northeast Japan.

The exceptionally high SST during this winter is considered to be due to the northward extension of the warm Kuroshio Current, which typically flows below 37° N but reaches the waters off Sanriku (39–40° N). The latest study reports that an unprecedented marine heatwave, characterized by periods of abnormally high seawater temperatures, occurred in northeast Japan in the summer of 2023 (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Takemura, Ito, Umeda, Maeda, Tanimoto, Nonaka and Nakamura2024). Because this phenomenon had continued during the subsequent winter, the warm water entered the Oshika Peninsula, disrupting the cold Oyashio Current from the north and resulting in elevated SSTs during the winter. Additionally, there has been a global increase in marine heatwaves and this trend is expected to continue (Hobday et al., Reference Hobday, Alexander, Perkins, Smale, Straub, Oliver, Benthuysen, Burrows, Donat, Feng, Holbrook, Moore, Scannell, Gupta and Wernberg2016; Miyama et al., Reference Miyama, Minobe and Goto2021). It is, therefore, expected that the number of sea turtle cases that occur during unusual seasons will continue to increase. The reported observations of green turtles have been increasing in the northern part of the East China Sea and East (Japan) Sea (~37.5° N) accompanied by increasing seawater temperatures (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park, Park, Kim, Cho, Yang, Han, Cho, Shim, Hong and An2024).

The waters off the Sanriku Coast, including the current study site, are one of the most productive areas in Japan, where cold Oyashio water and warm Kuroshio water interact (Hanawa and Mitsudera, Reference Hanawa and Mitsudera1987; Sugimoto and Tameishi, Reference Sugimoto and Tameishi1992). However, with the recent rise in seawater temperature, the annual catch of important cold-water fishery species (e.g. chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), Japanese sand lance (Ammodytes japonicus), Japanese common squid (Todarodes pacificus), North Pacific krill (Euphausia pacifica)) have declined, while that of warm-water species (e.g. Japanese jack mackerel (Trachurus japonicus), hairtail (Trichiurus lepturus), red seabream (Pagrus major), Japanese blue crab (Portunus trituberculatus) have increased in recent years (Takahashi, Reference Takahashi2022). It may, therefore, be necessary to consider this case as a distribution shift of marine organisms around the study site. However, we cannot conclude whether this represents a habitat shift based on these two cases of green turtles occurrence. Further cases should be collected on a continuous monitoring survey to reveal this potential trend.

The green turtle is primarily known as an herbivore, according to previous dietary studies (as reviewed by Bjorndal, Reference Bjorndal, Lutz and Musick1997). In the last decade, the population of green turtles in the Ryukyu archipelago (southern Japan) has increased by approximately 80% (Kameda et al., Reference Kameda, Wakatsuki, Takase, Nakanishi and Kamezaki2023). As a result, there has been increasing concern about the potential overgrazing of seagrass by the turtles (Takeyama et al., Reference Takeyama, Kohno, Kuramochi, Iwasaki, Murakami, Kenshi, Ukai and Nakase2014). It is currently unlikely that the presence of a few green turtles in this area for an extended period would have an immediate effect on seaweed and seagrass beds because the Sanriku coastal waters (including the Oshika peninsula) are characterized by an abundance of seaweeds and seagrass (Ministry of the Environment, 2011). However, if the biomass of seaweeds and seagrass significantly decreases due to future changes in the marine environment, overgrazing may occur due to the increased presence of green turtles. It is, therefore, essential to conduct monitoring surveys not only on important fisheries species but also on non-fisheries species, including sea turtles, to evaluate changes in the distribution of marine organisms and their effects on fisheries resources under climate change.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315424001048.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all volunteers from the Fisheries Cooperative Association of Michishita, who turned over the sea turtle in this study. We acknowledge Maptool (http://www.seaturtle.org/maptool/) used to generate the map of the study site. We thank 3 anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments on this manuscript. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author Contributions

Takuya Fukuoka conceptualized this study and wrote first draft of manuscript. Kaito Fukuda conducted the field investigation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial Support

This study is financially supported by the management expenses of Behavior, Ecology and Observation Systems, the University of Tokyo.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical Standards

The present study was incidentally conducted during a tag and release program where loggerhead and green sea turtles were caught by commercial fixed nets as bycatch in the Sanriku Coastal waters and then turned in by fisherman to researchers. The program was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethic Committee of the University of Tokyo, and the protocol of this study was approved by the committee (P23-21).

Data availability statements

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of the study are available within the article.