Seenku (ISO 639-3: sos) is a Western Mande language of the Samogo group, whose other members include languages like Dzùùngoo (Solomiac Reference Solomiac2014), Jowulu (Djilla, Eenkhoorn & Eenkhoorn-Pilon Reference Djilla, Eenkhoorn and Eenkhoorn-Pilon2004), and Duungooma (Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler1996), spoken on either side of the Mali-Burkina Faso border. The endonymic language name Seenku [sɛ̃́ː-kû] (also spelled on Ethnologue as Seeku) literally means ‘thing of the Sɛ̃ː ethnicity’, but it is widely known to outsiders as Sembla (variant spelling Sambla), which doubles as an exonym for the ethnicity. Seenku has two primary dialects, Northern and Southern, spoken in villages approximately 40 km west of Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso (see map in Figure 1). This study focuses on the more populous southern dialect, particularly the variety spoken in and around the large village center of Bouendé (local name [ɡ͡béné-ɡũ̏]), with a population of approximately 12,000 speakers; the Northern dialect, spoken around the village center of Karangasso (local name [təmî]), has a population of approximately 5000 speakers and was the subject of a sketch grammar (Prost Reference Prost1971). The southern dialect had until recently received little scholarly attention, with the exception of a Master's thesis on the morphophonology at the Université de Ouagadougou (Congo Reference Congo2013), but is now the subject of the NSF Documenting Endangered Languages grant supporting this research (BCS-1664335). Other published work includes McPherson (Reference McPherson2017a, b, c, d).

Figure 1 Map of Burkina Faso, with the location of Seenku indicated.

The phonetics and phonology of Seenku are of particular interest given the heavy amount of morphophonological reduction in the language, even compared to closely related languages. Despite being a Western Mande language, Seenku has more in common with Southern Mande languages like Dan (Vydrine Reference Vydrine2004), which have also moved towards monosyllabicity with complex segmental and tonal systems.

The present Illustration is based on the speech of two consultants, SCT (a 27-year-old male) and GET (a 21-year-old female). Both speakers are also fluent in Dioula and proficient in French.

Consonants

Seenku has a largely symmetrical consonant inventory with five places of articulation (bilabial, alveolar, palatal, velar, and labiovelar). Both plosives and affricates are attested at the alveolar place of articulation, though the contrast is neutralized before high vowels (described below). In native vocabulary, /l/ and /w/ occur primarily at the beginning of functional elements (clitics) or word-internally, though loanwords, primarily from Dioula, have altered this distribution. /p/ is a marginal phoneme, only attested in a small number of words.

The phoneme /p/ is only found in a small handful of words in the lexicon. The affricates and labiovelars are likewise less common than other consonantal phonemes. The nature and behavior of the non-contrastive coda nasal, transcribed as (ŋ), will be discussed in the section ‘Syllable and word structure’ below.

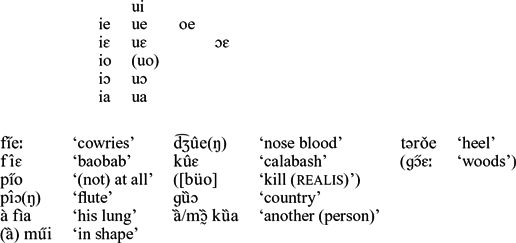

In terms of phonetic realization, voiced obstruents are fully voiced, with long negative VOT, while voiceless obstruents are unaspirated. The waveforms of [dɛ̀ɛ̈] ‘accustomed’ and [tɛ̀ː] ‘termites’ are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 (a) Voiced alveolar stop in [dɛ̀ɛ̈] ‘accustomed’, (b) Voiceless alveolar stop in [tɛ̀ː] ‘termites’, both spoken by GET.

Consonant allophony

In so-called ‘sesquisyllabic words’ (discussed further below), the allophone [ɾ] is commonly attested in C2 position, e.g. [kəɾȕ] ‘hyena’.Footnote 3 It is not clear whether this is an allophone of /d/ or /l/; the former never appears as such, and the latter is restricted to appearing between labials and the vowels /e/ or /a/ on the surface. In related Dzùùngoo (Solomiac Reference Solomiac2014), [ɾ] is treated as an allophone of /d/, occurring both intervocalically and at the beginning of many functional elements, but in Seenku, all liquid-initial functional elements begin with [l]. Given sporadic cases of free variation between [ɾ] and [l] (e.g. [ȁ kərá] ~ [ȁ kəlá] ‘its tail’), I will treat [ɾ] as an allophone of /l/, though it would also be possible to analyze it as an allophone of /d/.

Before a nasal vowel in a sesquisyllabic word, [ɾ] is nasalized to [ɾ̃], as in [dəɾ̃ĩ̋] ‘children’ (cf. [dəɾô(ŋ)] ‘child’). There appears to be a partial merger in this position with C2 /n/, which likewise can be heard leniting to [ɾ̃], as in [fáná] ~ [fəɾ̃á] ‘also’ (loanword from Dioula fáná).Footnote 4 Nevertheless, this variation seems to be lexically-specific; the word for ‘woman’, [məni̋], exceptionlessly contains [n], while intransitive ‘drink’ is [məɾ̃ĩ̂], presumably from an underlying representation /mlĩ̂/ (cf. transitive [à mḭ̀] ‘drink it’), and another transitive–intransitive pair /ɟű/ ‘say (trans)’ (in the example phrase [ȁ d͡ʒú] ‘say it’) vs. /ɟlúi̋/ [ɟəɾú̯i̋] ‘say (intrans)’).

For further discussion of sesquisyllabic word structure and consonantal distribution, see section ‘Syllable and word structure’ below.

High vowels /i/ and /u/ are responsible for much of the consonant allophony in Seenku. Before high vowels, alveolar plosives and affricates are neutralized to affricates (with the exception of one verb, [tíi] ‘accept’, and one noun [tûŋ] ‘pot’, which retain their plosive pronunciation); for monomorphemic roots, the underlying representation is indeterminate (e.g. [t͡sû] ‘hippopotamus’ could be either /tú/ or /t͡sú/, see below for tone), but alternations can be found in verbal morphology, where realis verb stems often undergo diphthongization with the insertion of [i] or [u] before the root vowel. Verbs with initial /t/ will thus show [t] ~ [t͡s] alternations between the irrealis and the realis (e.g. [tɔ̀] vs. [t͡si̯̋ɔ] ‘leave’).Footnote 5 The alveolar fricative /s/ has a palatal allophone [ʃ] before high vowels, as in /sȉ/ [ʃȉ] ‘water jar’, /sű/ [ʃű] ‘antelope’, except in certain ideophones like [súː] ‘directly’, where [s] is variably preserved. There is likewise neutralization of velar and palatal stops (oral and nasal) to palatal, but only before the high front vowel /i/. If, however, a velar + high vowel sequence is derived through vowel hiatus resolution, the velar does not palatalize (/kí/ or /cí/ [cî] ~ [t͡ʃî] ‘house’, but /kɛ́ í wó tȅ/ [kí wó tȅ] ‘it is yours (pl)’). Palatal stops have an optional (but common) palato-alveolar affricate allophone before all high vowels, thus /ɟũ̏/ [d͡ʒũ̏] ‘hill’ and verbal alternations such as [ɟó] vs. [d͡ʒi̯̋o]/[d͡ʒî̯o] ‘see’ (irrealis vs. realis).Footnote 6 The palato-alveolar allophone is also found initially in sesquisyllabic words where C2 is velar, i.e. /ɟɡȅ/ [d͡ʒəɡȅ] ‘dog’, possibly due to dissimilation that eases articulation.Footnote 7

Lenition is sometimes seen in C2 position of sesquisyllabic words. First, before a nasal vowel, /ɡ/ is variably realized as [ŋ], e.g. /f(ə̏)ɡã̂/ ~ [fə̏ŋã̂] ‘power’. Second, some speakers regularly lenite C2 /b/ to [β], as in /dbî/ [dəβî] ‘brick oven (for roasting shea nuts)’.

Finally, there is interspeaker variation in the realization of affricates and palatals. What has been described until now is characteristic of most people's speech (in the experience of the author), but younger speakers, especially younger females, have a tendency to swap alveolar and palatal affricates. For instance, while SCT (the 27-year-old male) pronounces words like /cȉe/ ‘die’ as [t͡ʃȉe], GET (the 21-year-old female) says [t͡sȉ̯e].Footnote 8 When asked about differences, both explain that women tend to speak ‘more finely’, though recordings of older women do not show the same behavior. It is unclear whether this is a change in progress, led as is typical by younger women (Labov Reference Labov1990).

Vowels

Seenku has a very large vowel inventory, with between seven and nine oral vowel qualities, five nasal vowel qualities, fourteen oral diphthongs, and (at least) six nasal diphthongs; length is in principle contrastive for all vowels (monophthongs and diphthongs alike), though there are many accidental gaps for rarer vowel phonemes.

Monophthongs

The core oral and nasal vowel inventory is typical for a Mande (or West African) language: a contrast between open and close mid vowels for oral vowels, with the contrast neutralizing in nasal vowels. It is not clear whether this mid vowel contrast is purely height-based (as in many Mande languages) or a tongue root distinction [±ATR].

Figure 3 shows a normalized vowel plot based on recordings made with our male and female speakers. The vowel plot was produced by the NORM Vowel Normalization and Plotting Suite from the University of Oregon using the Lobanov normalization method. Formant values were extracted in Praat using a formant extraction script by Lennes (Reference Lennes2003), which takes the midpoint of each vowel. Data were then visually inspected and corrected by hand. The high back nasal vowel /ũ/ was particularly problematic, with the Praat formant tracker often unable to disentangle F1 and F2. In this case, spectral slices were taken from the midpoint of each vowel and formants identified by hand.Footnote 9

Figure 3 Normalized vowel plot of oral and nasal monophthongs in Seenku.

Note that while phonologically we can speak of the contrast in mid vowels neutralizing for nasal vowels, from a phonetic standpoint, high and mid-close are more similar, with this ostensibly being the contrast neutralized in nasal vowels. Note finally that /ɔ̃/ is particularly variable in GET's speech.

While a vowel inventory with seven oral qualities is sufficient for the bulk of the vocabulary, there appears to be a marginal contrast in back vowels, shown in parentheses above. A handful of words contain a vowel that plots phonetically between /o/ and /ɔ/ in terms of F1 and F2 (shown in Figure 2 above), but F3 tends to be lower. It has an audible pharyngealized quality to it and also sounds hyper-rounded. Speakers’ metalinguistic judgments dictate that it is neither /o/ nor /ɔ/, though the two speakers (neither literate in Seenku, as Seenku has no orthography) differ in writing it as either <o> or <ɔ>. The pharyngealized quality and low F3 are suggestive of a retracted tongue root vowel, either [o̙] or even [u̙]. The former falls in line with the fact that it appears intermediate between /o/ and /ɔ/, while the latter is compatible with the fact that this vowel behaves like high vowels in triggering consonant allophony (e.g. palatals are realized as palato-alveolar affricates and alveolar plosives are realized as alveolar affricates; /s/ varies between [s] and [ʃ]). Another hypothesis is that this vowel is underlyingly a diphthong /uo/, a gap in an otherwise rich diphthong inventory, which would explain the allophonic behavior of the preceding consonant. However, it would leave the pharyngealized quality and the fact that it is lower in the vowel space than /o/ unexplained, and additionally, [uo] is at times created through diphthong formation in verbs and it does not have this pharyngealized quality. It cannot be the diphthong /uɔ/, as there are minimal pairs differentiating the two. I will treat it here as RTR /u̙/, with the tongue root effects strong enough to raise F1 beyond the F1 of /o/.

This contrast would benefit from articulatory study.Footnote 10

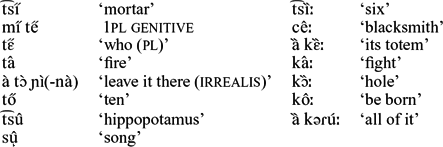

Minimal sets for short and long oral vowels are as follows:

Curiously, there is an accidental gap for long /uː/ in open class vocabulary; there is nothing to indicate that such a vowel should not be possible, given the otherwise symmetrical nature of the language, but the current dataset does not include any instances outside of adverbial or ideophonic words (ideophonic quantifier shown below).

Length appears to be contrastive for nasal vowels as well, though long nasal vowels are quite rare and currently restricted to two vowel qualities, /ɛ̃/ and /ã/:

Diphthongs

All diphthongs in Seenku are either back–front diphthongs at the same degree of aperture or rising sonority diphthongs. The diphthong-initial vocalic element is non-moraic (a glide), but it retains its degree of aperture (that is, vowel contrasts do not reduce to a binary [j] vs. [w]). Non-moraic high vowels have the same allophonic effects on the preceding consonant as full vowels. Because the diphthong-initial element is non-moraic, diphthongs can also be either long or short without creating super-heavy vowels. The attested oral diphthongs are as follows:

All of the above examples are lexical (underlying) with the exception of [bű̯o] ‘kill (realis)’, whose diphthong is the result of realis mood (cf. irrealis [ȁ bó] ‘kill him’) and [ɡɔ̯̋ɛː] ‘woods’, derived from plural formation. Back–front diphthongs like the latter are commonly created in morphological processes like the nominal plural and the verbal antipassive. These back–front diphthongs always maintain the same vowel height and length, e.g. [fɾ̃ɔ̃̏] ‘monkey’ vs. [fɾ̃ɔ̯̃̀ɛ̃] ‘monkeys’, [à kòː] ‘sing it’ vs. [kȍ̯eː] ‘sing’.

A smaller number of nasal diphthongs can be identified, though others may be found in a larger dataset:

Vowel allophony and vocalic processes

After alveolar affricates, /ɛ/ centralizes to [ɘ]: /tsɛ̋/ [tsɘ̋] indefinite (as in /bɛ̏ː tsɛ̋/ ‘some pig’). Between palatals and a front vowel, /u/ can be fronted to [y]: /ɲũ̋ĩ/ [ɲỹ̯̋ĩ] ‘honey’.

The most common process affecting vowels is hiatus resolution. Content words are all consonant-initial, but common pronouns and functional elements can be simply V. The following observations can be made about hiatus resolution in Seenku:

• If V1 is a round (back) vowel, a diphthong is formed with compensatory lengthening of V2: /mó ȁ/ [mô̯aː] ‘1sg 3sg’ (from ‘I have killed him’, recording 035, this section).

• If V1 is /i/, a diphthong is likewise created: /sĩ̌ ȁ/ [sı̯̃̀ ã̈ː] ‘be 3sg’ (from ‘I am leaving it there’, recording 045, consonant section).

• If V1 is /a/ and V2 is /i/, there is variation between the full elision of /a/ and the coalescence of the two vowels to [ɛ]: /ȁ ɲá̰ í sɡɔ̌ ŋɛ́/ [ȁ ɲí səɡɔ̌ ŋɛ́] ~ [ȁ ɲɛ́ səɡɔ̌ ŋɛ́] ‘it is not good’, with the former more common than the later.

• If V1 is /ɛ/ and V2 is /i/, V1 can either delete (as in /kɛ́ í wó tȅ/ [kí wó tȅ] ‘it is yours (pl)’) or the /ɛi/ sequence can be realized as [e] (/lɛ̏ í/ [lé] ‘narrative logophoric’), from the fourth line of the narrative in the transcription section below.

• If V1 is any of the remaining vowels /e ɛ a/ and V2 is other than /i/, then V1 is elided without compensatory lengthening. /kɛ́ á wó tȅ/ [ká wó tȅ] ‘it is yours (sg)’.

Syllable and word structure

Most native vocabulary is either monosyllabic or ‘sesquisyllabic’ (Matisoff Reference Matisoff1990, Pittayaporn Reference Pittayaporn, Enfield and Comrie2015), a term more commonly applied to Southeast Asian languages. On the surface, sesquisyllabic words consist of an initial half-syllable (a consonant–schwa sequence) followed by a full syllable (e.g. [təɡɛ̂] ‘chicken’). These have evolved from iambic reduction of disyllabic words, still attested in other Mande languages. There is some question as to the underlying representation of these words in Seenku, specifically whether the schwa (or some vowel) is underlying or epenthetic. To avoid the need to posit an extra vowel quality restricted to this position, I treat schwa as epenthetic. This analysis is consistent with the fact that the schwa never contributes tone (though it can realize the tone melody of the word) and it is often absent before liquids, one of the least phonotactically restricted onset clusters cross-linguistically (e.g. [(ȁ) blě] ‘big’).Footnote 15 Further, when asked to pronounce sesquisyllabic words slowly, speakers rarely introduce a full vowel quality in the initial sesquisyllable, lending support to the fact that the reduction that led to sesquisyllabic words is diachronic rather than synchronic.

This is not to say that longer words are unattested. Disyllabic words can be found, with or without an initial half syllable, such as [d͡ʒȕ̙ŋ͡ma̋] ‘cat’ or [ȁ ɲəŋámɛ́] ‘mix it’. But such words are rare compared to mono- and sesquisyllabic words.

Consonant distribution and positional restrictions

All consonants, with the exception of /l/ and /w/, can occur freely in word-initial position in open class vocabulary (nouns and verbs), but in C2 position of sesquisyllabic words, no voiceless consonants are allowed (with the exception of one instance of /f/) and only a subset of voiced consonants are attested, illustrated in the following words:

The attested combinations of C1 and C2 in sesquisyllabic words are shown in Table 1, where gray cells indicate presence and white cells indicate absence. The cells containing ‘x’ are cells where C1 and C2 are homorganic; all of these cells are empty, showing that Seenku has an OCP principle on underlying consonant clusters. The exception is initial /s/, which can co-occur with /l/ (with the surface allophone [ɾ]). This is reminiscent of the exceptional nature of initial /s/ in clusters in languages like English. No sesquisyllabic words begin with affricates or with the labiovelar nasal. The other labiovelars are only attested in the following words: [(ȁ) k͡pɾṵ́] ‘(its) stomach’, [ɡ͡bəɡǎː(ŋ)] ‘shed’, [ȁ ɡ͡bəɡá] ‘its hoof’, and [ɡ͡bəɡɛ̂] ‘approach’.

Table 1 Co-occurrence table for C1 and C2 in sesquisyllabic words.

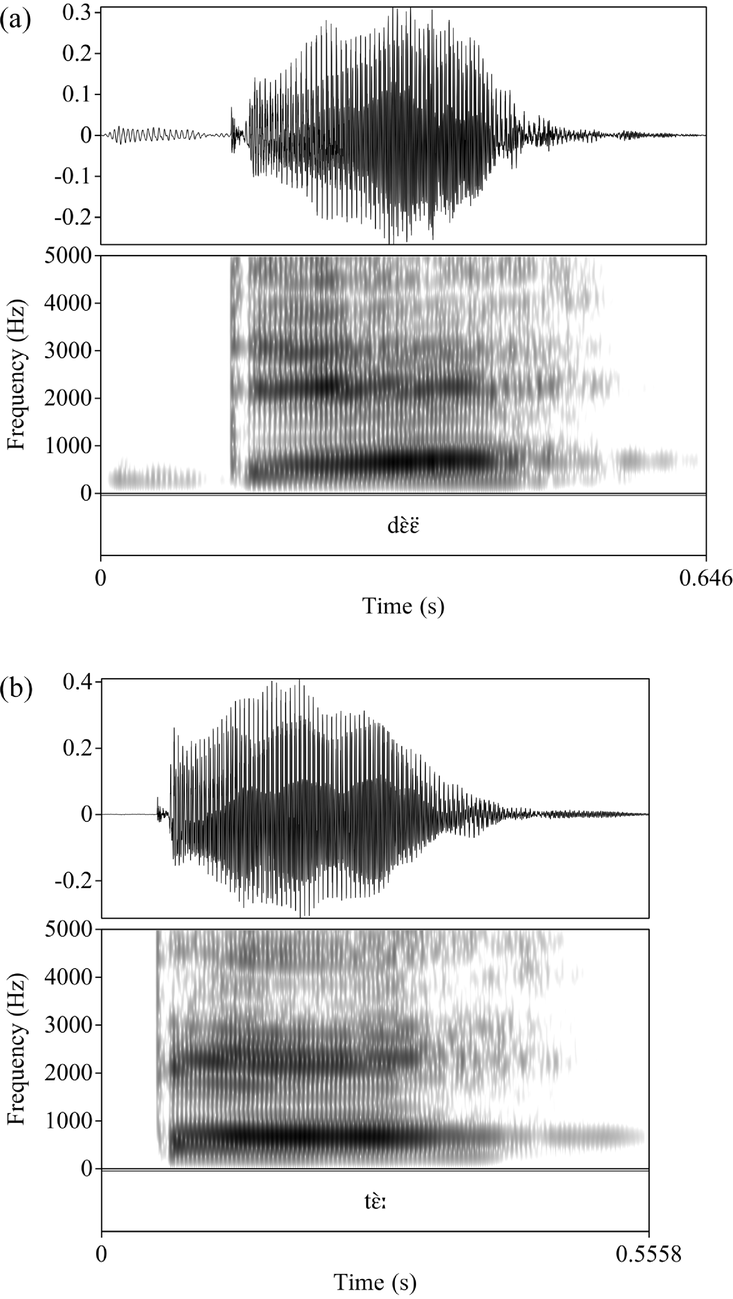

Coda nasals

The other complication in Seenku syllable structure is the question of nasal codas. With the exception of a nasal coda (whose place of articulation is non-contrastive), all syllables are open. However, this nasal coda is only fully realized when the word is phrase-medial and followed by an obstruent, in which case the nasal assimilates to the place of articulation of this obstruent. This is shown in Figure 4, where the coda nasal of /sɔ̋(ŋ)/ ‘sky’ is realized as an alveolar nasal before /t/ in the compound /sɔ̋(ŋ)-ta̋/ ‘sun’ (lit.: ‘sky-fire’).

Figure 4 Realization of the coda nasal as a homorganic stop before an obstruent (/sɔ̋(ŋ)-ta̋/ → [sɔ̋n-ta̋] ‘sun’), from the North Wind and the Sun spoken by SCT.

Before a following nasal, the nasal coda is deleted, as shown in Figure 5 /sɔ̋(ŋ) nǎ bɛ̃́/ ‘it (lit.: sky) will rain’. It should be noted that the /n/ in Figure 5 is not lengthened when preceded by an underlying nasal coda; it is the same length here as it would be in any other environment, indicating that the nasal coda is truly deleted.

Figure 5 Deletion of the coda nasal before a following nasal in /sɔ̋(ŋ) nǎ bɛ̃́/ ‘it will rain’, spoken by SCT.

If followed by an approximant, the nasal coda will optionally turn the approximant into its corresponding nasal stop (/l/ → [n], /w/ → [m]), after which the nasal coda itself is deleted. However, this behavior is variable, depending both on the speaker and phonological phrasing. Sonorants are typically turned into nasal stops within a phonological phrase and simply nasalized across a phonological phrase boundary (for instance, between a subject and a predicate), but as Figure 6 shows, this is subject to variation. SCT, in the North Wind and the Sun, pronounces the imperfective particle /wɛ̏/ with an initial [m] after the coda-final verb /dzĩ̋(ŋ)/ ‘put’ (Figure 6a), while GET pronounces it with a nasalized sonorant [w̃] after the same verb in another text (Figure 6b).

Figure 6 (a) Realization of /w/ as [m] after /dzĩ̋(ŋ)/ ‘put’, from North Wind and the Sun, spoken by SCT, (b) Realization of /w/ as [w̃] after /dzĩ̋(ŋ)/ ‘put’, in the phrase ‘put that on it’ spoken by GET.

In both cases the nasal coda itself goes unrealized. These examples also illustrate that nasal codas are lexically attested after nasal vowels in addition to oral vowels. Note that nasal vowels in underlyingly open syllables (i.e. without the nasal coda) never nasalize a following sonorant. Preliminary study of the behavior of nasal codas in context suggests that variation is both within-speaker (free variation) and between-speaker (variation in rates of nasalization in different environments). It may also be sensitive to speech rate or speaking style, as SCT's recording of the North Wind and the Sun was a more careful and practiced passage of speech than the spontaneous utterance by GET in Figure 6b above.

Some of the most challenging behavior is found when the nasal coda is before a pause. Here, it is optionally pronounced, with its place of articulation determined by the preceding vowel (palatal for front vowels, velar for back vowels, and uvular after the low vowel /a/); but often it is simply omitted, with or without late nasalization of the preceding vowel. As GET astutely observed, ‘it is as if you start by saying [a] and finish by saying [ã]’. These words contrast with both fully oral and fully nasal vowels (/kâ/ [kâ] ‘griot’, /kǎ̰/ [(ȁ/í) kã̌] ‘white’ vs. /kâ(ŋ)/ [kâ̯ã̯] ‘granary’, where the sequence of two extra-short vowels is intended to indicate a single short vowel with late nasalization). This three-way contrast can be seen in the spectrograms in Figure 7, for ‘griot’, ‘granary’, and ‘white’, respectively (female speaker GET). The shift towards a nasal vowel can be seen about halfway through the vowel in Figure 7b for ‘granary’, particularly in higher formants.

Figure 7 (a) Oral vowel in /kâ/ ‘griot’, (b) Half-nasal vowel in /kâ(ŋ)/ ‘griot’, (c) Nasal vowel in /kã̌/ ‘white’, all spoken by GET.

The same words pronounced by male speaker SCT are shown in Figure 8. The shift to a nasalized vowel is subtler for SCT, perhaps involving less nasal airflow in the case of the underlying nasal coda, though instrumental measurement would be required to test this hypothesis.

Figure 8 (a) Oral vowel in /kâ/ ‘griot’, (b) Half-nasal vowel in /kâ(ŋ)/ ‘granary’, (c) Nasal vowel in /kã̌/ ‘white’, all spoken by SCT.

Tone

The Seenku tone system is arguably among the more complex in Africa, in terms of the number of contrasts. There are four contrastive levels, referred to as extra-low (ȁ), low (à), high (á), and super-high (a̋), and abbreviated X, L, H, S, respectively, for convenience. As I have argued elsewhere (McPherson Reference McPherson, Payne, Pacchiarotti and Bosire2017b), there is evidence for a feature system underlying these tones, such as that proposed by Yip (Reference Yip1980) and elaborated upon by Pulleyblank (Reference Pulleyblank1986). This system is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Tone features for Seenku tone inventory.

In addition to evidence from register agreement in contour tones (discussed below), the feature system is supported by tonal morphology, with featural affixes (Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1996) accounting for tone raising and tone lowering in inflectional categories such as the plural or the perfective; see McPherson (Reference McPherson2017a, b) for further discussion.

Most morphologically simplex open class vocabulary contrasts only three levels, X, H and S, with the second lowest tone L phonologically conditioned (by a following S tone) or morphologically derived (typically in plural formation, by raising of X due to the [+raised] plural affix (McPherson Reference McPherson2017a), or in a process of ‘tonal compounding’ whereby two X-toned words in specific morphosyntactic configurations both become L; see McPherson Reference McPherson2016). However, lest we think L is always derived, it is attested lexically in adverbs, ideophones, proper names, and numerals.Footnote 16 All examples in the recordings are embedded in the frame sentence [mó ___ sɔ́ː] ‘I sold __’ to highlight the tonal contrasts, with the exception of /sá/ ‘cry’, which appears in the phrase [ȁ nǎ sá ŋɛ́] ‘he will not cry’.

There are few minimal pairs for level H-toned words, due to a tonotactic restriction against final H in nouns; instead, H must be followed by X, creating an H–X contour tone, indicated in the transcription system with the circumflex. The diachronic origins of this X tone are likely in a definite marker (attested, for example, in Dzùùngoo; Solomiac Reference Solomiac2014), though it has lost all definite meaning in Seenku. Nominal (near) minimal pairs including H–X include:

Table 3 lays out the other attested two-tone contour tones in the language, with examples. Down the left-hand side is Tone 1, and along the top Tone 2. Note that where a single tone diacritic is unavailable to mark a contour, long vowels can carry each of the component level tones.

Table 3 Attested contour tones in Seenku.

a In the phrase mó ȁ bã̈ ‘I have hit him’.

b In the phrase ȁ sĩ̌ ŋáa̋ nɛ̋ ‘he is yawning’.

Of these, only H–S and L–S are lexical in nature, and even H–S is vanishingly rare. This means that the two most common lexical contours, L–S and H–X, both share a common [raised] feature. S–X is morphologically derived in the perfect, by suffixing X to an S-toned verb; H–X was addressed above. The three contours S–H, H–L, and X–H are derived through a common process by which enclitics are elided, lengthening the vowel of the previous word and adding its tone. For instance, /mi̋ lɛ́/ ‘1pl subordinate’ is often elided to [mi̋í] with a long vowel and an S–H contour tone; /ȁ lɛ́/ ‘3sg subordinate’ similarly is realized as [ȁá] with an X–H contour.Footnote 19 H–L contours are created in tonal compounding, where an underlying /H–X X/ sequence becomes [H–L L], as in /ɡɔ̂ː wɛ̏/ [ɡɔ́ɔ̀ wɛ̀] ‘with wood’.

Tritone contours are also attested. In nouns, we find X–H–X (presumably /X–H/ underlyingly, with a tonotactically-enforced final X): /dȁá(ŋ)/ [dȁâŋ] ‘hanging basket holder’, /ɡɔ̏ɔ̂(ŋ)/ [ɡɔ̏ɔ̂ŋ] ‘hibiscus’. In verbs, the same process of perfect formation that creates S–X contours with S-toned verbs creates L–S–X contours on X-toned verbs: [nàä] ‘come (perfect)’. Finally, elision of the S-toned past tense clitic /lɛ̋/ after subjects can create unusual trough-shaped H–X–S contours, e.g. /dô(ŋ) lɛ̋/ → [dôõ̋] ‘child (past)’.

Despite the large number of level contrasts, Seenku still shows downstep and downdrift, whereby specifically S is lowered following [–upper] tones. I use the term downstep to refer to the situation in which there is no surface realization of the triggering [–upper] tone, and downdrift to refer to the situation in which the [–upper] tone is realized. The latter is also referred to in the literature as automatic downstep (e.g. Stewart Reference Stewart1983, Connell Reference Connell2001), and it is indeed automatic in Seenku, applying to any sequence [+upper][–upper]S.

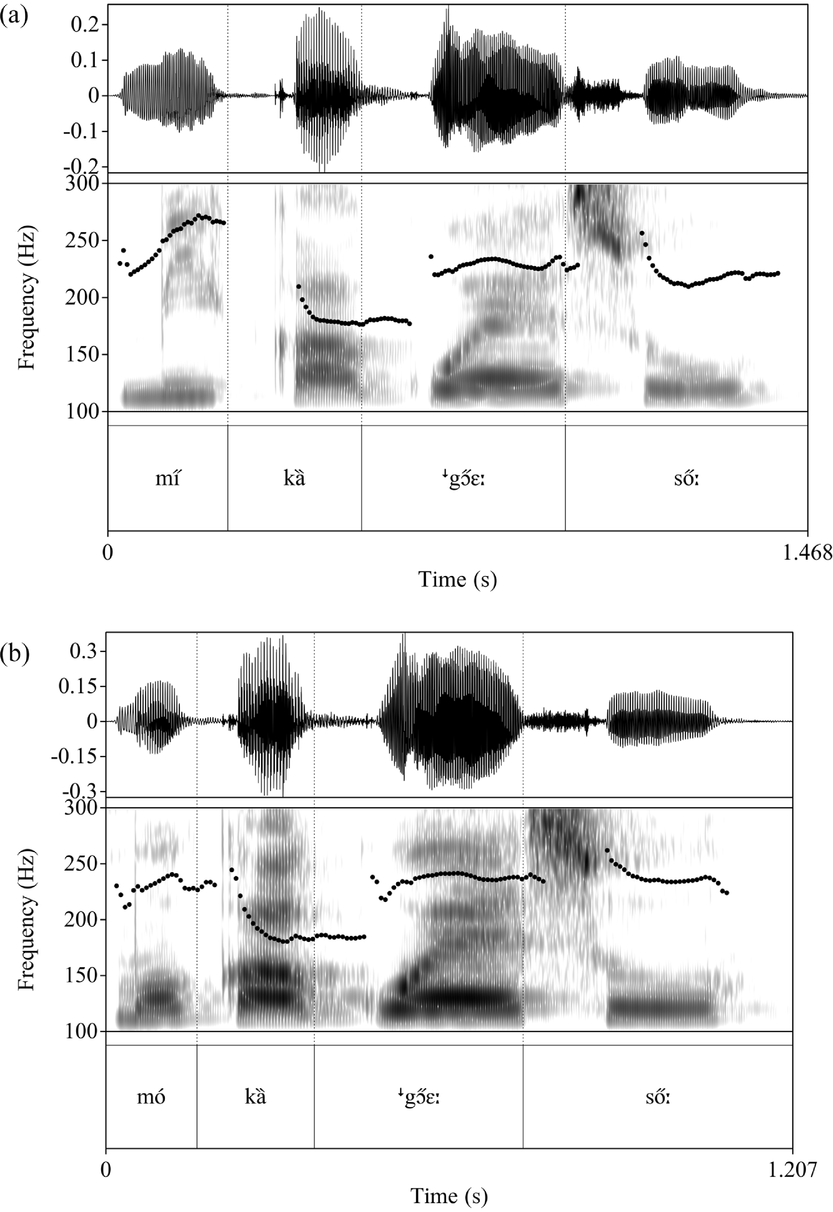

Unlike analyses of downstep that invoke the spreading of register features (e.g. Snider Reference Snider1990), Seenku downstep and downdrift cannot be the result of a spread of [–upper], since downstepped S is pronounced at approximately the same level as H (with which it shares a feature [+upper]) rather than at the level of L (the result of spreading [–upper]). Downdrift in the environment S#X#S and H#X#S is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9 (a) Downdrift in the environment S#X#S in [mi̋ kȁ ↓gɔ̋ɛː sőː] ‘we go gather woods’ (b) Downdrift in the environment H#X#S in [mó kȁ ↓gɔ̋ɛː sőː] ‘I go gather woods’, both spoken by GET (where S = super-high, H = high, and X = extra-low).

The amount of downdrift is the same regardless of whether the initial tone is S or H (approx. 56 Hz for GET). Figure 9b shows that downstepped S is pronounced at nearly the same level as the preceding H tone.

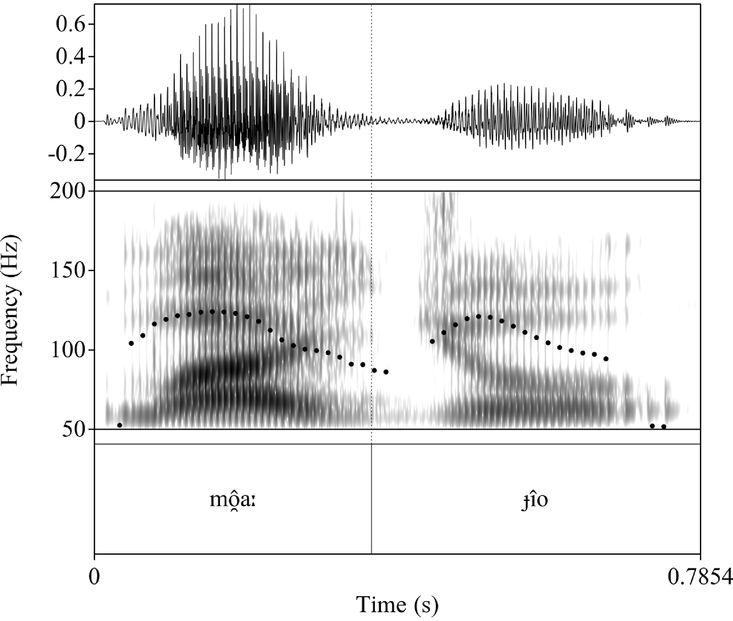

Curiously, H does not appear to undergo downdrift; this can be seen at multiple points in the North Wind and the Sun, including in the first line [mô̯aː dʒî̯o] ‘I saw it’, where the second H tone after the H–X contour is pronounced at the same level as the first, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 No downdrift in the context H-X#H-X in the phrase /mó ȁ ɟîo/ ‘I saw it’ from the North Wind and the Sun, spoken by SCT.

Downstep is attested through contour tone simplification of L–S contour tones to ↓S after a [+upper] tone (H or S) and before a non-S tone. This is shown between S and H in Figure 11.

Figure 11 Downstep of S resulting from contour-tone simplification in the phrase /mi̋ nǎ gɔ̂ː sȍ:/ ‘we will gather wood’, spoken by SCT.

Once again, ↓S is pronounced at nearly (though not entirely) the same level as the following H. Because the distinction is maintainted between H and S after ↓S, with H pronounced lower than ↓S, we cannot treat the downstepped tone as the phonological equivalent of H. This is consistent with the fact discussed above that downstep and downdrift do not appear to follow from the spread of tone features, which would change one tonal category into another.

Between two S tones, L–S simplifies to L, in a process referred to in the literature as ‘tonal absorption’ (Hyman & Schuh Reference Hyman and Schuh1974). The remaining L triggers downdrift on the following S, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12 Tonal absorption turning L-S to L before a following S in the phrase /mi̋ nǎ gɔ̋ɛː sőː/ ‘we will gather woods’, spoken by SCT.

Transcription of recorded passage

The following is a broad (B) and narrow (N) transcription of a Seenku translation of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’, as spoken by SCT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Documenting Endangered Languages grant BCS-1664335. I am grateful to my consultants, SCT and GET, for their help in recording all of the examples, to André Radtke for his help managing the recordings, and to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors are my own.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100318000312.