Khuzestani Arabic (ISO 639-3) is a minority language spoken in the southern west of Iran, in Khuzestan province (see Figure 1). The majority of its speakers live in Ahwaz, Howeyzeh, Bostan, Susangerd, Shush, Abadan, Khorramshahr, Shadegan, Hamidiyeh (Balawi & Khezri Reference Balawi and Khezri2014: 107), Karun, and Bawi. According to Blanc (Reference Blanc1964: 6), this variety of Arabic is closely related to the Gelet subgroup of Mesopotamian dialects.Footnote 1 This dialect is in contact with Bakhtiyari Lori and Persian (Iranian languages of the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European language family), as well as Iraqi Arabic. The lexis of the dialect predominantly contains Arabic words, but it also has several Persian, English, French, and Turkish loanwords.

Figure 1. Map of Khuzestan province (Iran).

There are idiosyncratic sociolinguistic differences among speakers from different cities and tribes (examples are provided in the consonants and vowels sections). Almost all Khuzestani Arabic speakers are bilingual in Arabic and Persian; the latter is the official language of the country. However, in the northern and eastern cities of Khuzestan, Lori is also spoken besides Persian, and in this region the Arabic of KamariFootnote 2 Arabs, is remarkably influenced by Lori. At the center of cities such as Abadan, some of the younger generations, especially females, tend to speak mainly Persian. Furthermore, a number of parents speak only Persian with their children at home.

Nowadays, Khuzestani Arabic has a significant number of speakers in Iran. Based on a survey conducted by the Ministry of Culture in 2010, 33.6% of the population of Khuzestan (i.e. around 1.6 million people) are Arabs. Nevertheless, if the existing shift from Khuzestani Arabic to Persian continues to the next generations, it will be on the edge of extinction in the near future.

Contrary to many Arabic dialects, Khuzestani Arabic has received little scholarly attention. Ingham (Reference Ingham1997, Reference Ingham and Versteegh2007) gives a preliminary description of the dialect. Also there are two almost totally identical M.A. theses on this dialect; Abiyyat (Reference Abiyyat2005) and Balawi (Reference Balawi2008) present a traditional letter-based description of the phonological system of Khuzestani Arabic. Shabibi (Reference Shabibi2006) discusses the influences of Persian on this dialect. Alifar’s (Reference Alifar2015) sociolinguistic study indicates that Khuzestani Arabic spoken in Abadan, Khorramshahr, and Shadegan is the prestigious one among young speakers in Ahwaz.

The purpose of the present paper is to describe the principal features of the phonological system of Khuzestani Arabic.Footnote 3 The participants of this study included 10 female and 20 male adult native speakers from Abadan, aged between 25 and 55 years. They held a diploma or a BA degree and spoke Arabic at home. The phonemic value of the sounds was determined via minimal pairs/ sets, selected from among 800 collected words. Vowels and certain consonants were also studied acoustically. The data were recorded in a quiet room and analyzed by Praat software (version 5.3.56). The acoustic vowel data and other recordings in this article, including the narrative, are based on samples recorded from a 54-year-old male speaker, a school principal and poet from Abadan. Hence the information given in the subsequent parts is based on Abadani variety. However, in referring to a number of sociolinguistic differences, there are three samples from a 30-year-old Susangerdi female speaker of Sawāri tribe and one sample from a Khorramshahri male speaker aged 27. At the end of the paper, the transcription of The North Wind and the Sun story based on the pronunciation of the mentioned Abadani male speaker is provided.

Consonants

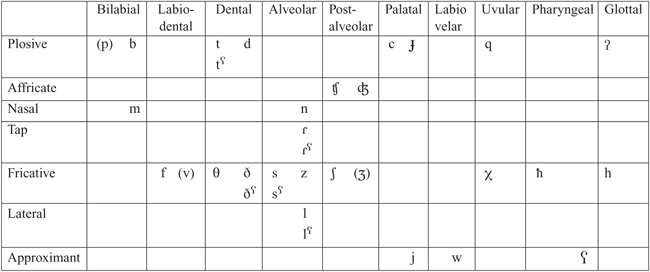

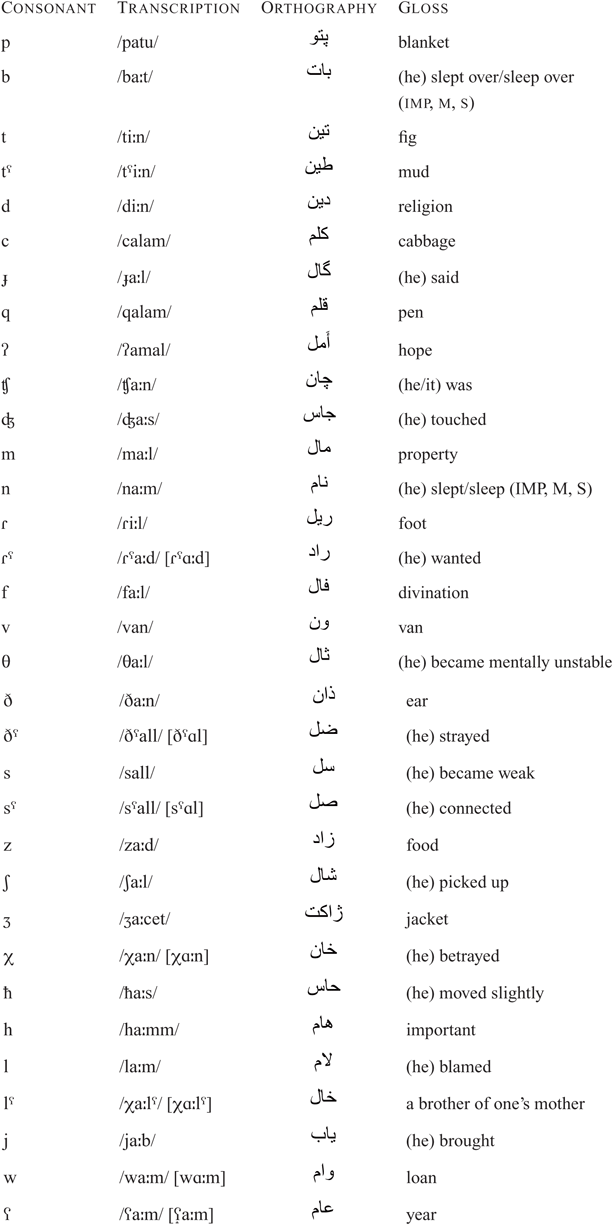

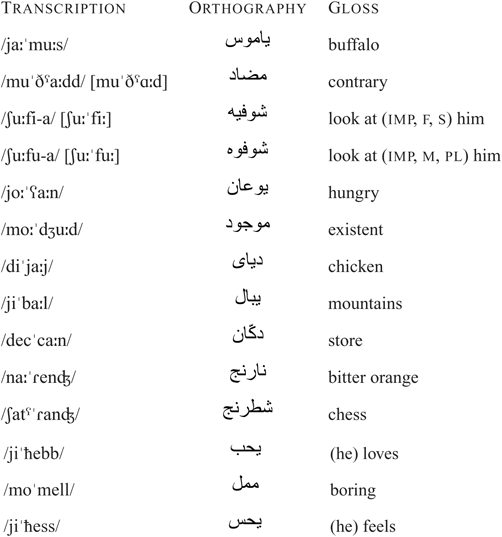

Khuzestani Arabic has a rich consonantal inventory, with 33 consonants, five of which have pharyngealization as secondary articulation (traditionally known as emphatics).

The consonants of Khuzestani Arabic are seen in 10 places and seven manners of articulation. Stops include /(p) b t tˤ d c ɟ q ʔ/. The voiceless bilabial plosive /p/ appears in loanwords only (e.g. /patu/ ‘blanket’, from Persian). Phonologically, the two front dorsal consonants have a palatal place of articulation under the influence of Persian and are hence represented as /c ɟ/. These two consonants have a post-palatal (velar) allophone before central/back vowels and a palatal allophone elsewhere (before front vowels as well as after all vowels).Footnote 4 The Old Arabic (OA) /q/ and /ɣ/ have merged into /q/ (e.g. OA /qaːlib/ > /qaːleb/ ‘template’, OA /ɣaːlib/ > /qaːleb/ ‘dominant’). This voiceless uvular stop has a voiced uvular fricative allophone between two vocoids as in /melʕaqa/ [melʕaʁa] ‘spatula’ and /aqwa/ [ʔaʁwɑ] ‘stronger’. The OA glottal voiceless sound /ʔ/ is generally deleted medially, resulting in compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel when it occurs syllable-finally. This glottal sound is sometimes replaced by /j/ (e.g. OA /maːʔ/ > /maːj/ ‘water’, OA /miʔa/ > /mijja/ [mijje] ‘hundred’).

There are two post-alveolar affricates in Khuzestani Arabic, namely /ʧ/ and /ʤ/. The voiceless affricate /ʧ/ comes from OA /k/ in the context of front vowels (e.g. OA /baːkir/ ‘early’ > /baːʧeɾ/ ‘tomorrow’). In Abadan and other cities like Ahwaz, the OA /ʤ/ has shifted to /j/ in some words (e.g. OA /ʤalaba/ > /jaːb/ ‘(he) brought’), while it has remained unchanged in others (e.g. OA /ʤaːsa/ > /ʤaːs/ ‘(he) touched’). As a sociolinguistic variation, the same consonant is replaced by /ʒ/ for Sawāri, Ḥeydari, and Sāʿedi tribes from Susangerd and Hamidiyeh (/ʒaːb/ ‘(he) brought’). Meanwhile, this OA consonant is preserved in Khorramshahr (/ʤaːb/ ‘(he) brought’).Footnote 5

Fricatives include /f (v) θ ð ðˤ s sˤ z ʃ (ʒ) χ ħ h/. Like /p/, /v/ and /ʒ/ only appear in loanwords (e.g. /van/ ‘van’, /ʒaːcet/ ‘jacket’). All three phonemes appear as /b/, /w/, and /ʤ/, respectively, in the pronunciation of older generations. The OA /dˁ/ has merged with /ðˁ/ to result in / ðˁ/ (e.g. OA /ðˁall/ > /ðˁall/ [ðˁɑl] ‘(he) stayed’, OA /dˁall/ > /ðˁall/ [ðˁɑl] ‘(he) strayed’). In addition to the original form, the reflexes of OA /q/ are /c/ (e.g. OA /waqt/ > /wact/ [wɑcet] ‘time’), /ɟ/ (OA /qaːla/ > /ɟaːl/ ‘(he) said’), and /ʤ/ (e.g. OA /qariːb/ > /ʤeɾiːb/ ‘near’, OA /ʃarqiː/ ‘eastern’ > /ʃaɾʤi/ ‘very hot and humid weather’). This is similar to many other Arabic varieties such as the dialects of Muslims in Baghdad (Erwin Reference Erwin1969 [2004]), Southern Iraq, Gulf coast, and central Palestinian villages (Holes Reference Holes2004: 74). The voiced pharyngeal consonant /ʕ/ appears mainly as an approximant in the pronunciation of the speakers of this dialect, although a more closed allophone (fricative) may appear word-initially and word-finally in the pronunciation of some speakers.

Sonorant consonants include /m n ɾ ɾˤ l lˤ j w ʕ/. In OA, the emphatic /lˁ/ exists only in the word /alˁlˁaːh/ [ʔɑlˁlˁɑːh] ‘God’ and its derived forms except when it is preceded by /i/ (Fischer Reference Fischer and Rodgers2002: 18). Similar to Iraqi Arabic (Erwin Reference Erwin1969 [2004]), other examples containing this sound can be found in Khuzestani Arabic (e.g. /χaːlˁ/ [χɑːlˁ] ‘a brother of one’s mother’).

Finally, /l/ of the definite article completely assimilates to all the following coronal consonants.

Vowels

Khuzestani Arabic has 11 vowels: /i iː e eː a aː u uː o oː ɑ/. The traditional quadrilateral vowel plot of Khuzestani Arabic monophthongs is as follows:

There are five phonetic diphthongs in this dialect: [ie ai ou ei au]. In a number of words, [ei] and [ie] correspond to OA /aj/. Figure 2 contains the acoustic vowel plot of Khuzestani Arabic monophthongs and diphthongs.

Figure 2. Vowel plot of Khuzestani Arabic Monophthongs and diphthongs (male speaker).

This vowel plot is based on F1 and F2 formant measurements of one repetition of words by the 54-year-old Abadani male speaker mentioned above. Formant measurements were done by hand at vowel midpoint. Due to contextual restrictions on some vowels, all 11 vowels could not be placed in one minimal set. The words utilized for drawing the vowel plot are as follows:

Monophthongs

Diphthongs

The phoneme /ɑ/ only exists in loanwords from Persian (e.g. /ɑʃ/ ‘a thick Iranian soup’, /ɑbpɑʃ/ ‘watering can’) and other languages (e.g. /motcɑɾ/ ‘motorcar’, /ɑncɑl/ ‘on call’). This low back vowel is sometimes fronted (e.g. Persian /jaxʧɑl/ > Khuzestani Arabic /jaχʧaːl/ ‘refrigerator’). For the remaining 10 vowels, vowel length is contrastive and each short vowel has a long counterpart. Speakers tend to use /e/ and /o/ in place of the OA short high vowels /i/ and /u/ (e.g. OA /min/ > /men/ ‘from’, OA /dubb/ > /dobb/ ‘bear (m)’). In word-medial position, the two OA diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ are generally monophthongized to the long vowels /eː/ and /oː/ (e.g. OA /ʕajʃ/ ‘life’ > /ʕeːʃ/ ‘bread’, OA /lawn/ > /loːn/ ‘color’, OA /jawm/ > /joːm/ ‘day’). However, in some cases OA /aj/ has changed to /je/ (e.g. OA /lajl/ > /ljel/ ‘night’, OA /bajt/ > /bjet/ ‘home’). Except in some monosyllabic words, the OA long vowels /iː uː aː/ have lost their [+long] feature word-finally (e.g. OA /ʃaɾqiː/ > /ʃaɾqi/ ‘eastern’).

The vowels /a aː/ generally change into a back low vowel ([ɑ ɑː]) in the context of emphatics and sometimes when they are adjacent to /ɟ w χ q ħ ʕ h ʔ/ (e.g. /χaːn/ [χɑːn] ‘(he) betrayed’, /ðˁall/ [ðˁɑl] ‘(he) strayed’). In a few examples, the same change is observed in the context of labial consonants (e.g. /jumma/ [jummɑ] ‘mother (voc)’). Erwin (Reference Erwin1969 [2004]: 48) explains that in Iraqi Arabic labial consonants can be pharyngealized (e.g. /bˤ mˤ fˤ/). In Khuzestani Arabic, the vowel change in the environment of labial consonants suggests that they can be pharyngealized as well, although the phonemic status of these consonants has not been confirmed in our study. The application of this phonological process is related to sociolinguistic differences; for example, unlike speakers from Abadan, Ahwaz, and Khorramshahr, the three Sawāri, Ḥeydari, and Sāʿedi tribes from Susangerd and Hamidiyeh, utter the OA words /anaː/ ‘I’ and /maːʔ/ ‘water’ with changing the first vowel into a low back vowel, namely [ʔaːne] ‘I’ and [maːj] vs. [ʔɑːne] ‘I’ and [mɑːj] ‘water’.

The raising of final /a/ (traditionally known as imāla ‘inclination’), which has been recognized in many Arabic varieties, such as the dialects of Amman (Al-Wer Reference Al-Wer, Miller, Al-wer, Caubet and Watson2007: 68–69), Beirut (Naїm Reference Naїm and Versteegh2006: 276), Damascus (Lentin Reference Lentin and Versteegh2006: 547), and Muslims of Baghdad (Jastrow Reference Jastrow and Versteegh2007: 418), also exists in Khuzestani Arabic. The level of raising and the extent to which this process occurs is different from one dialect to another. In Khuzestani Arabic, final /a/ raises to become a mid front vowel [e]. This process occurs in the feminine gender marker and the 3rd person singular masculine and feminine oblique morphemes /-a/ and /-ha/.

Raising of final /a/ of the feminine gender marker

Raising of final /a/ of the 3rd person singular masculine oblique morpheme

Raising of final /a/ of the 3rd person singular feminine oblique morpheme

It is also seen in other examples and seems to have spread considerably to the instances of /a/ in final position.

Raising of final /a/ in other origins of this sound

Despite the widespread application of the raising process in Khuzestani Arabic, examples can still be found in which this final sound remains unchanged or is backed, mainly in the vicinity of consonants with posterior place of articulation.

Absence of final /a/ raising process in the feminine gender marker

Absence of final /a/ raising in the 3rd person masculine and feminine oblique morphemes /-a/ and /-ha/

Absence of final /a/ raising in other origins of this sound

Syllable structure

The following six syllable types are observed in Khuzestani Arabic:

Empty onsets are filled by a glottal stop at the phonetic level. Only vowels fill the nucleus position. Generally, consonant clusters are not allowed. However, there are a few loanwords (e.g. /ʒest/ [ʒest] ‘gesture’) with a CC cluster in coda position. Phonologically, in Arabic words, CVCC and CVːCC are also allowed, provided that the final consonants are identical. Identical and adjacent second and third radical consonants do not appear word-finally and only appear when followed by a vowel, e.g.:

Arabic words with identical 2nd and 3rd radical consonants

Thus, /ʧebb/ ‘pour!’ appears as [ʧeb] when followed by silence or a consonant-initial morpheme. The same morpheme appears as [ʧebb] when followed by a vowel, as in [ʧebbi].

The prohibition of final clusters in Khuzestani Arabic has resulted in the insertion of an auxiliary vowel between the two consonants where OA or a loanword contains such clusters. This is illustrated in the following two lists:

Vowel insertion in word-final consonant clusters in Khuzestani Arabic

Loanword adaptation in Khuzestani Arabic

If a morpheme with an empty onset occurs after words ending in a consonant cluster, no auxiliary vowel is added. Instead, as seen in the examples in (1) below, the second element of the consonant cluster fills the empty onset position.

Stress

It appears that the stress rules of Khuzestani Arabic are similar to those in Iraqi Arabic described by Erwin (Reference Erwin1969 [2004]: 13–74). If the last syllable of a word is heavy (CVː(C)(C), CVCC), it carries primary stress, e.g.:

Word-final stress in Khuzestani Arabic

This statement holds true regardless of the number of syllables in a word and regardless of the presence or absence of other long vowels in the preceding syllables.

If the final syllable is not heavy, stress falls on the heavy syllable nearest to the end of the word. If there are no heavy syllables among the last three syllables of the word, stress falls on the penultimate syllable in two-syllable words and on antepenultimate syllable in all others.

Non-final word stress in Khuzestani Arabic

There are some grammatical features which affect the stress pattern of the word. For example, in words ending in the suffix /-a/ ‘him/it (m)’, stress falls on the syllable preceding that suffix. For the feminine object pronoun /-ha/, stress also falls on the preceding syllable. If that syllable is an open syllable, its vowel is lengthened:

Transcription of the recorded passage ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

The story’s orthographic transcription is in the Khuzestani Arabic orthography. The speaker on whose recording the transcription is based was a 54-year-old adult male native speaker from Abadan.

English version

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveler came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveler take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveler fold his cloak around him; and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shined out warmly, and immediately the traveler took off his cloak. And so the North Wind obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.

Transcription

hɑwɑ͜ ʃʃimaːl ‖ wu͜ ʃʃames ‖ ʧaːnu jitʃaːʤɾuːn ‖ biʔan jaːhu minhum ʔɑʁwɑ ‖ ʔebħiːnethe͜ wɑsˤɑl musaːfeɾ min͜ iddaɾo(b) ‖ ʔu ʧaːn laːf ʕala ɾuːħa ʕabaːje daːfije ‖ ʔohmɑ͜ twɑːfqɑu ‖ cilman minhum ‖ ɟidaɾ ʔasɾaʕ ‖ ʔinezzeʕ͜ ilmusaːfeɾ ʕabaːjte ‖ ʔohwɑ ʔɑʁwɑ ‖ baʕdien ‖ hɑwɑ͜ ʃʃimaːl ‖ habb͜ ebcil quːte ‖ laːcen ‖ cilma ʧaːn jiheb ʔacθaɾ ‖ ʔelmusaːfeɾ jilif͜ ilʕabaːje ʕala ɾuːħa ‖ ʔacθaɾ ‖ ʔu binnaha:je ‖ hawa͜ lʃimaːl ‖ jaːz min muħaːwɑle ‖ baʕadhe͜ ʃʃames ‖ bidat tisˤhɑɾ͜ ebħaɾɑːɾathe ‖ wu͜ lmusaːfeɾ foːɾan ‖ nizaʕ͜ elʕabaːje ‖ ʔu bennatiːʤe ‖ hawɑ͜ ʃʃimaːl ‖ ʔenʤubaɾ jeʕteɾef ʔebquwwɑt͜ iʃʃames ‖ ʔacθaɾ minne ‖

Orthographic version

Abbreviations

- 3

third person

- du

double

- f

feminine

- F1

1st formant

- F2

2nd formant

- imp

imperative

- m

masculine

- n

noun

- OA

Old Arabic

- pl

plural

- s

singular

- voc

vocative

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks to Ms. I. Shamus, Mr. Donya’izadeh, Mr. Musavi, Mr. Ghayyem, and other Khuzestani Arabic speakers in Abadan who helped us in gathering the required data and recording samples. We also are extremely grateful to the editor of the Journal of International Phonetic Association and reviewers of this Illustration for their comments and suggestions that helped in the clarification of certain points and improved the article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100319000203.