The Bai language (![]() ) is spoken by approximately 1.6 million people in northwest Yunnan Province, China. Of the 25 minority languages spoken in Yunnan, where 33% of the population are ethnic minorities and 67% are Han Chinese, the Bai ethnic minority is second in population only to the Yi (Wiersma Reference Wiersma1990, Reference Wiersma, Thurgood and LaPolla2003; 2010 census). Bai is classified as a Tibeto-Burman language (Xu & Zhao Reference Xu and Zhao1964, Reference Xu and Zhao1984), although arguments have been raised as to its possible early Sinitic origins (Starostin Reference Starostin1994, Reference Starostin1995). A summary in French reviews Chinese loanwords, ancient Bai, and comparative Bai dialects (Dell Reference Dell1981). The historical influence of Chinese on Bai has been significant, but evidence is not compelling that Bai is Sinitic (Norman Reference Norman, Thurgood and LaPolla2003: 73). There are three major dialects of Bái: Jiànchuān (

) is spoken by approximately 1.6 million people in northwest Yunnan Province, China. Of the 25 minority languages spoken in Yunnan, where 33% of the population are ethnic minorities and 67% are Han Chinese, the Bai ethnic minority is second in population only to the Yi (Wiersma Reference Wiersma1990, Reference Wiersma, Thurgood and LaPolla2003; 2010 census). Bai is classified as a Tibeto-Burman language (Xu & Zhao Reference Xu and Zhao1964, Reference Xu and Zhao1984), although arguments have been raised as to its possible early Sinitic origins (Starostin Reference Starostin1994, Reference Starostin1995). A summary in French reviews Chinese loanwords, ancient Bai, and comparative Bai dialects (Dell Reference Dell1981). The historical influence of Chinese on Bai has been significant, but evidence is not compelling that Bai is Sinitic (Norman Reference Norman, Thurgood and LaPolla2003: 73). There are three major dialects of Bái: Jiànchuān (![]() ), Dàlĭ (

), Dàlĭ (![]() ), and Bìjiāng (

), and Bìjiāng (![]() ). The data in this illustration represent the variety of Jianchuan (jian1239, BCA). The third author (

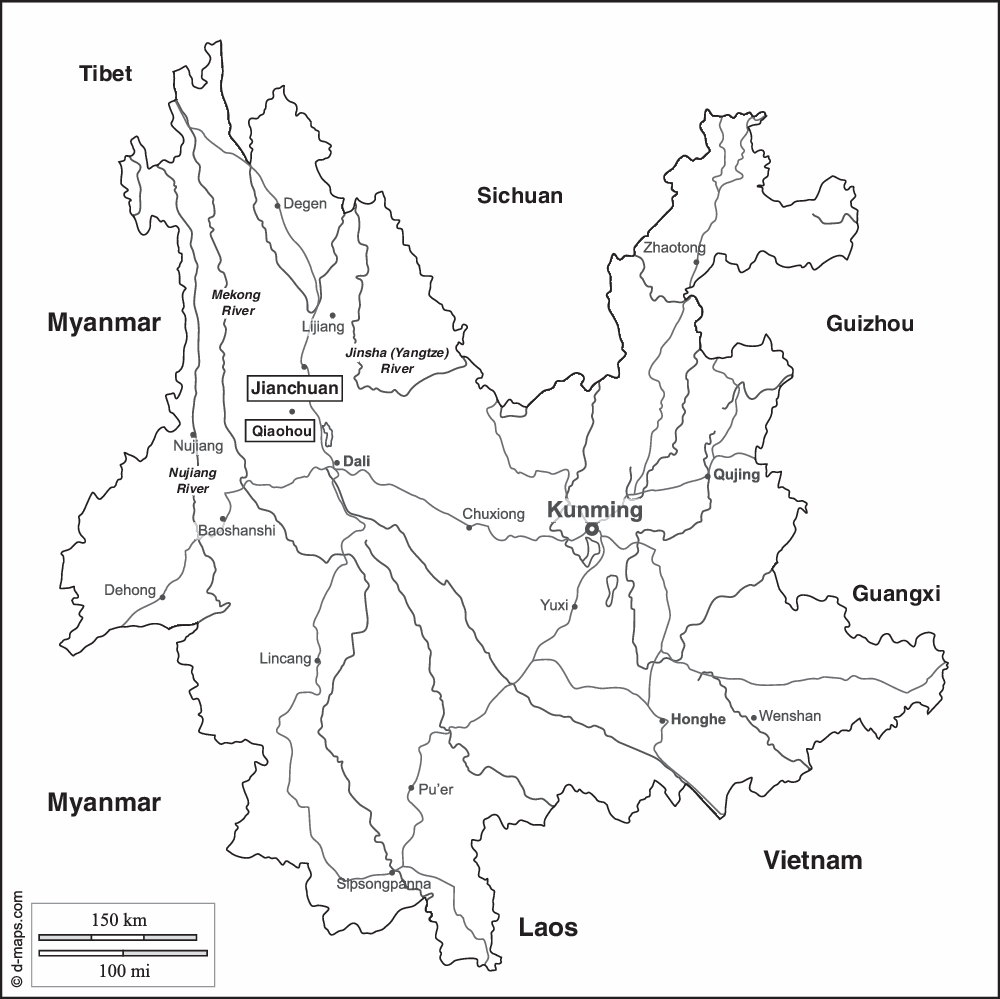

). The data in this illustration represent the variety of Jianchuan (jian1239, BCA). The third author (![]() ), who was about 60 years old at the time of recording, is a male native of the Jianchuan region, originating from QiÁohǒu, a mountain village some 50 km southwest of Jianchuan city – a remote area known for salt mining and where the language has been less influenced by modern Chinese. These locations are indicated on the map of Yunnan (the southwesternmost province of China in an intensely minority-language-populated area) in Figure 1. The traditional geographical link from Qiaohou is to Jianchuan to the north rather than to Dali to the south, and many of the most distinctive characteristics of Jianchuan Bai described here are not found in Dali Bai.

), who was about 60 years old at the time of recording, is a male native of the Jianchuan region, originating from QiÁohǒu, a mountain village some 50 km southwest of Jianchuan city – a remote area known for salt mining and where the language has been less influenced by modern Chinese. These locations are indicated on the map of Yunnan (the southwesternmost province of China in an intensely minority-language-populated area) in Figure 1. The traditional geographical link from Qiaohou is to Jianchuan to the north rather than to Dali to the south, and many of the most distinctive characteristics of Jianchuan Bai described here are not found in Dali Bai.

Figure 1 The Province of Yunnan in southwestern China. The county of Jianchuan is located in the northwest of the province, just south of the corridor where the three major rivers (Nujiang, Mekong, and Yangtze) flow out of Tibet. The city of Jianchuan and the town of Qiaohou are indicated with outlines. Map from d-maps.com.

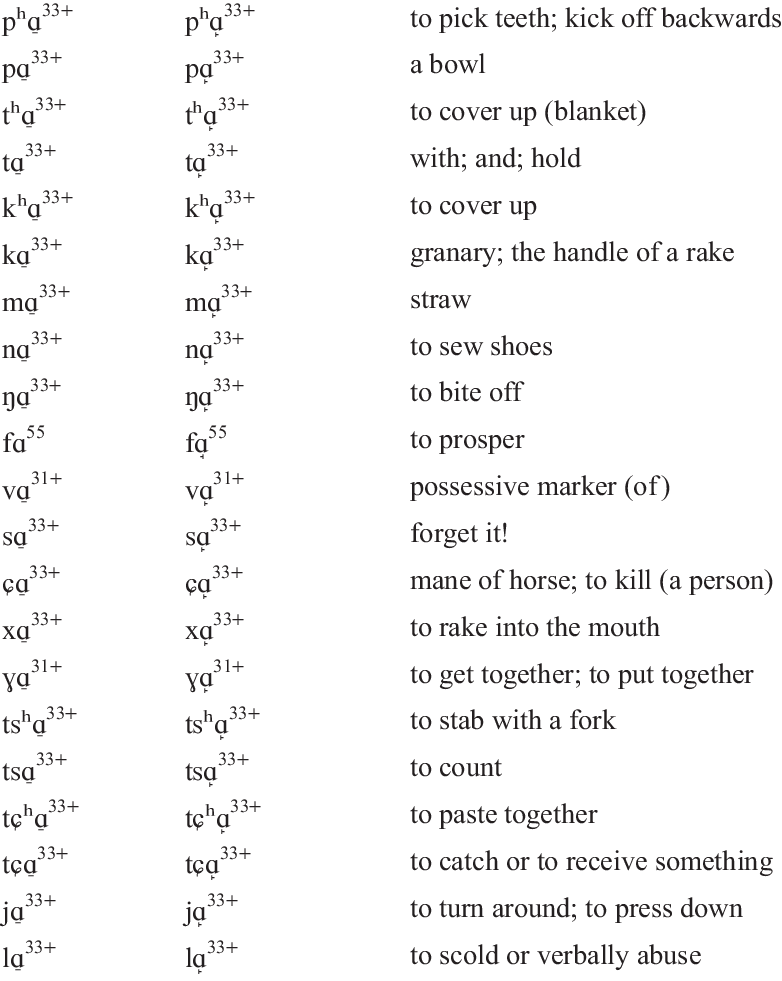

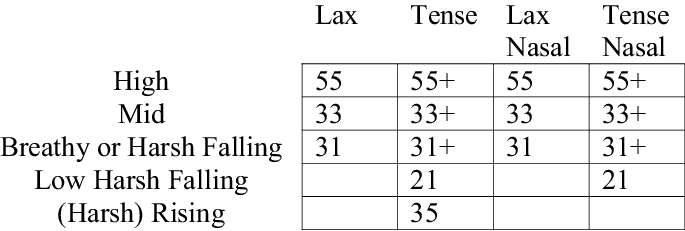

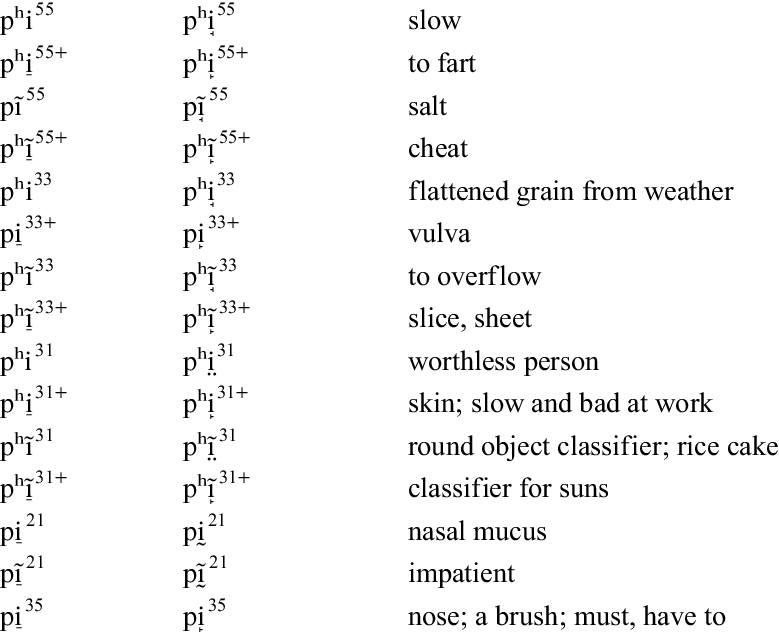

Jianchuan Bai possesses a set of pitch contrasts: 55, 33, 31, 21 and 35 in the Chao tone system (Xu & Zhao Reference Xu and Zhao1964). Perhaps the most telling characteristic of this variety is the contrast between two systematic tonal register series, lax and tense (Dai Reference Dai and Dai1990), realized as contrasting phonation types depending on the pitch level – modal, breathy or degrees of harshness – demonstrating the essential relationship between laryngeal constriction, phonation type and pitch (see Edmondson & Li Reference Edmondson and Li1994, Esling et al. Reference Esling, Moisik, Benner and Crevier-Buchman2019). There is a great deal of variation across Bai dialects, and the same lax/tense (laryngeal constriction) contrast found in Jianchuan Bai is not generally present in other varieties such as Dali Bai. Even within the Jianchuan region, the forms described in this illustration will have altered with the generations along sociolinguistic lines over the past 60 years. The standard Bai inventory also includes a set of four retroflex (affricate and fricative) sounds to accommodate educated pronunciations of Beijing Mandarin loans, but these sounds have not been included here because they are not required by the local inventory, such loans popularly assuming a pronunciation that fits within the local parameters. In Jianchuan Bai, all rhymes (syllable codas), except /u/ and /ɑo/ (and /iɑo/ where attested), have nasalized as well as oral reflexes, although the distribution of such nasalized rhymes is limited. The presence of vowel nasalization is lexically distinctive in Jianchuan, while in Dali Bai, no nasalized rhymes are found. As observed by Starostin (Reference Starostin1994), some Jianchuan nasalization appears to be secondary rather than historical. A treatment of Bai phonology and of contrasts across dialects may be found in Opper (Reference Opper2017). Relevant reports on voice quality in other related languages can be found in Maddieson & Ladefoged (Reference Maddieson and Ladefoged1985) and Chen (Reference Chen1988). In the Consonant Chart below, sounds that occur phonetically in predictable phonological contexts are included in the inventory, between square brackets.

Consonants

Vowels

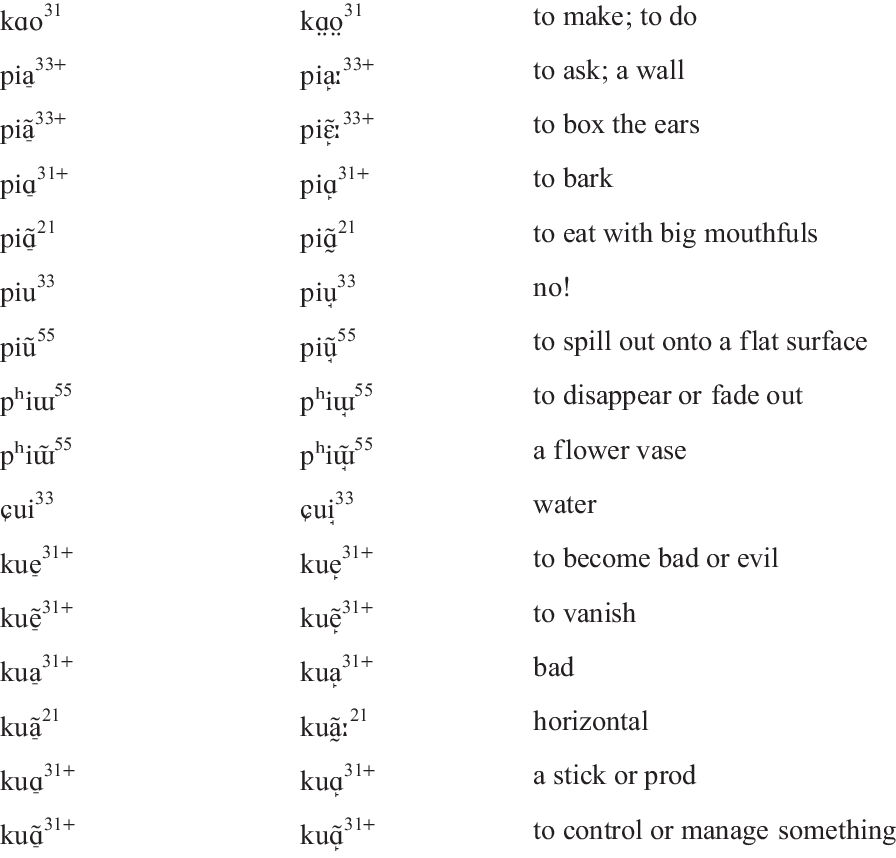

All vowels except /u/ have an oral reflex and a corresponding nasal quality. Nasality can be viewed either as a property of the vowel set or of the syllable paradigm (as a function of the tonal register set). The /vˌ vˌ˜/ vowels are fricativized vowels (meaning that the syllable maintains the posture of labiodental [v]). The examples are primarily from the two highest tone categories, for comparative clarity, and because they have the most elaborated distribution of vowels. Most of the examples are also from the tense register series, where the vowel is marked with a retracted underscore, as the retracted quality is a function of the tonal register category (Esling & Edmondson Reference Esling, Edmondson, Braun and Masthoff2002). It should be noted that tonal register (the combination of pitch levels and phonatory laryngeal state) plays a major role in the Jianchuan Bai sound system and that the use of lax or of tense register may change the perception of vowel quality, particularly in the case of the close oral fricative stricture for /vˌ vˌ˜/. The open front vowel /a/ has also been described as /ɛ/ (Wiersma Reference Wiersma1990, Reference Wiersma, Thurgood and LaPolla2003).

The syllable nucleus (or rhyme) of each vowel at tone 55, 33, and 31 is produced with either what has been called ‘lax’ register or ‘tense’ register. Vowels at tone 21 and 35 only have tense register. The phonetic meaning of lax register is that the laryngeal constrictor mechanism in the lower vocal tract is not engaged, while the phonetic meaning of tense register is that the laryngeal constrictor mechanism in the lower vocal tract is actively engaged (see Esling et al. Reference Esling, Moisik, Benner and Crevier-Buchman2019). The articulatory and phonatory ramifications of this contrast are explained in detail for each tone in the section on Tonal Register. The lexical examples presented in the Consonant list above are all, save one, words with tense register, due to the ease of completing the paradigm with an open vowel. Words in the above Vowel list are also mostly from the tense series. The Vowel Chart displays the basic vowel quality contrast between oral and nasal vowels, without reference to the effects of register, but each vowel will have a lower-vocal-tract register component, differing in quality according to the tone.

Because of the interactive role of nasality and of tonal register, vowel quality may be spread unevenly phonotactically across the open vowels. In this data set, for example, there are no examples of oral /ɑ/ in the lax register – only in the tense register. This may reflect the inherent association of retracted vowels with constricted laryngeal quality (Esling Reference Esling2005), but that relationship has yet to be evaluated systematically.

A clear example of the open-vowel phonemic contrast in the lax nasal series is

although the tone differs. The oral open-vowel contrast in the tense series is shown by

and

Tense /ã/ does contrast with lax /˜/, although with phonatory registers that would be counterintuitive if only the vowels (and not the dominant register system) were taken into account, in

Diphthongs: ɑo, ia, ia˜, iɑ, iɑ˜, iu, iu˜, iɯ, iɯ˜, ui, ue, ue˜, ua, ua˜, uɑ, uɑ˜. Although /iɑu/ or /iou/ is sometimes reported for Bai (Wiersma Reference Wiersma, Thurgood and LaPolla2003), a triphthong that is distinct from /iu/ does not occur in this speaker’s inventory.

Tonal register

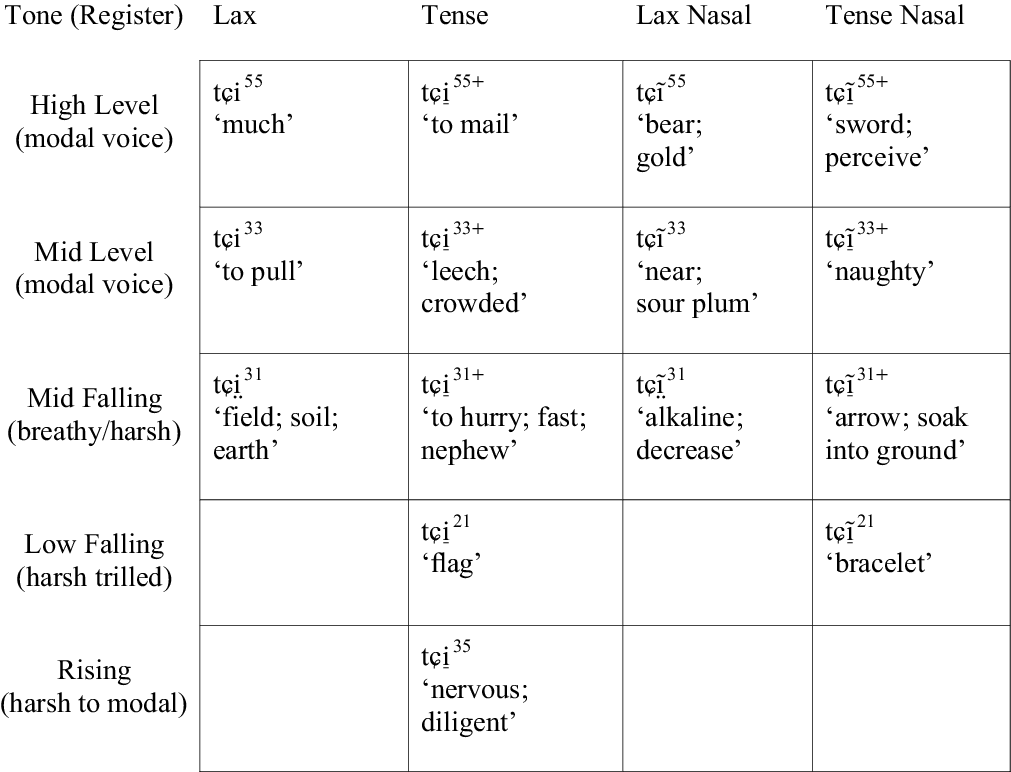

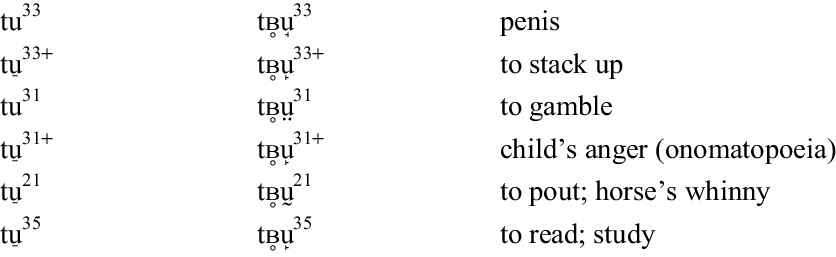

The most characteristic aspect of the phonetics of Jianchuan Bai is its tonal register system. Pitch levels or contours differ depending on the register series: lax or tense. The phonatory quality of each tone category changes as pitch height changes. The lax series reflects an open or unconstricted laryngeal/pharyngeal space, while the tense series reflects a laryngeally constricted posture of the lower vocal tract (Edmondson et al. Reference Edmondson, Jerold, John, Esling, Li, Jimmy, Harris and Lama2000, Reference Edmondson, Esling, Shaoni, Harris and Ziwo2001; Edmondson & Esling Reference Edmondson and Esling2006). The 55, 33, and 31 tones are slightly elevated in pitch when the syllable is tense (constricted). They are therefore marked with a plus as 55+, 33+, and 31+ in the tense series. Often, they are alternatively designated as 66, 44, and 42, respectively, to emphasize the pitch effect that accompanies laryngeal constriction in the language. Their phonatory quality is labelled as harsh voice, due to the constriction of the epilaryngeal space. The simultaneous longitudinal tension required for high pitch gives the 55+ tonal category a quality which approximates the isometric tightness referred to as ‘pressed voice’ in the speech science literature or the quality labelled ‘high-pitched harsh voice’ in descriptions of states of the larynx (Esling & Harris Reference Esling, Harris, Hardcastle and Beck2005), although the quality in Bai is moderate and not nearly as extreme as in canonical peripheral possibilities (especially in fluent running speech, which is probably true for spoken languages in general). Tones 33+ and 31+ differ in contour, but their phonatory quality and length also differ: 33+ has tighter constriction, while 31+ engages slight ventricular-coupled phonation (as in harsh voice or creaky voice) or aryepiglottic trilling with truncated duration. The lax 55 and 33 counterparts are relatively modal, while 31 is breathy voiced. The paradigm is asymmetrical at this point, as all pitch patterns can be tense (constricted), but breathiness is inherently lax (open/unconstricted) and cannot occur in the tense series, even though 31 and 31+ have the same pitch contour. Thus, at pitch contour 31, the phonation type distinction is maximized. Tone 21 combines the targets of low pitch and harsh phonation, which both require degrees of laryngeal constriction. Tone 21 therefore has no lax counterpart, as its phonation takes on the multiple source characteristics of a constricted epilaryngeal tube rather than an open epilaryngeal space. It is a sustained pharyngeal trill, i.e. with ventricular-coupled or aryepiglottic-fold vibration in addition to glottal vocal fold vibration. It approximates the quality labelled ‘low-pitched harsh voice’ among canonical states of the larynx (Esling & Harris Reference Esling, Harris, Hardcastle and Beck2005). The supraglottic oscillation contributes a periodic component at about half the frequency of the fundamental. Tone 35 has a rising pitch contour, beginning with the same periodic trilling as tone 21 (and occurs predominantly on recent Chinese loan words). Tone 35 has a laryngeally constricted onset, justifying its placement in the tense series, although it ends with modal voice. Each tonal register syllabic category has a corresponding nasal counterpart, except for the 35 tone. Each of the 15 contrasting syllables is illustrated with a /tɕ-/ initial consonant, in a complete paradigm, as well as with a /pʰ-/ or /p-/ initial consonant. Each list presents successions of contrastive pairs: the lax oral variant first, followed by the tense oral variant, then the lax nasal variant, followed by the tense nasal variant (except for tones 21 and 35, which have no lax counterparts, and tone 35, which has no nasal reflex). The second list illustrates that some consonant manners, e.g. aspiration, may be more compatible with the higher tones (55, 33) than with the lower trilled tones (21, 35), e.g. where unaspirated onsets may be more common.

Laryngoscopic videos

The tonal register paradigm is illustrated with laryngoscopic video data. Nasendoscopic videos show the articulatory activity in the larynx in an [i]-vowel context for the /tɕ-/ and the /pʰ-, p-/ paradigms listed above. The [i] vowel allows the lower vocal tract to be visualized more clearly over the back of the tongue. The /tɕi, tɕ̘/ paradigm may be schematized as follows:

Conventions

The palatal approximant /j/ can sometimes be realized as [ɲ] in the context of a nasal vowel:

A reduced [ə] occurs morphophonemically in the second syllable of words where that syllable bears a particle relationship to the first syllable, as in ‘sheep’ or in the following:

The /u/ vowel following /t/ yields a bilabial trill [

![]() ] that becomes voiced into the vowel:

] that becomes voiced into the vowel:

The fricativized vowels (labiodental-fricative vowels) may be realized as a syllabic [

![]() ], as an approximant [

], as an approximant [

![]() ] with raised-back vowel quality especially in nasal contexts, or as a syllabic nasal, e.g. as [ɱ] especially when the rhyme is nasal with no consonant onset, or as [ɳ] when the initial consonant is nasal:

] with raised-back vowel quality especially in nasal contexts, or as a syllabic nasal, e.g. as [ɱ] especially when the rhyme is nasal with no consonant onset, or as [ɳ] when the initial consonant is nasal:

The /ui/ diphthong can be realized with a fronted onset in the environment of alveolo-palatal consonants:

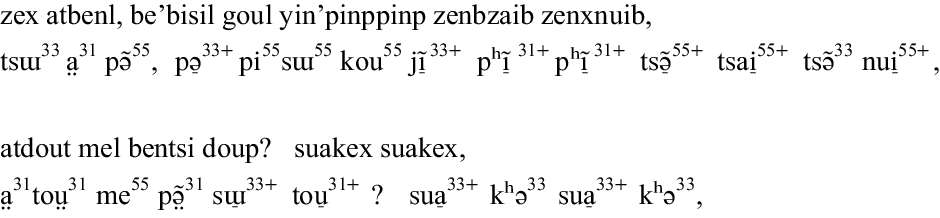

Transcription of recorded narrative passages

An example of a linguistically constructed utterance with words of only low falling (21 and 31+) tones in the tense register is:

An example of an utterance with words of only 31 tones with the lax-breathy register is:

‘The North Wind and the Sun’ is presented in Bai pinyin orthography and in narrow phonemic representation. Tense nuclei are redundantly marked as laryngeally constricted: [

![]() ], or trilled

], or trilled

![]() ] at 21 tone. Lax nuclei are unmarked, or marked as breathy voiced at 31 tone: [

] at 21 tone. Lax nuclei are unmarked, or marked as breathy voiced at 31 tone: [

![]() ].

].

Acknowledgements

Support for this research, in the laboratory and in the field, was provided by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We are grateful to Li Ya for her expertise and assiduous hard work in assembling, evaluating, translating, and transmitting Bai language data from China. We are indebted to Christopher Coey for the technical post-processing of audio and video files and to Patrick Szpak for graphics design and to two anonymous reviewers.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100319000379.

) is spoken by approximately 1.6 million people in northwest Yunnan Province, China. Of the 25 minority languages spoken in Yunnan, where 33% of the population are ethnic minorities and 67% are Han Chinese, the Bai ethnic minority is second in population only to the Yi (Wiersma

) is spoken by approximately 1.6 million people in northwest Yunnan Province, China. Of the 25 minority languages spoken in Yunnan, where 33% of the population are ethnic minorities and 67% are Han Chinese, the Bai ethnic minority is second in population only to the Yi (Wiersma  ), Dàlĭ (

), Dàlĭ ( ), and Bìjiāng (

), and Bìjiāng ( ). The data in this illustration represent the variety of Jianchuan (jian1239, BCA). The third author (

). The data in this illustration represent the variety of Jianchuan (jian1239, BCA). The third author ( ), who was about 60 years old at the time of recording, is a male native of the Jianchuan region, originating from QiÁohǒu, a mountain village some 50 km southwest of Jianchuan city – a remote area known for salt mining and where the language has been less influenced by modern Chinese. These locations are indicated on the map of Yunnan (the southwesternmost province of China in an intensely minority-language-populated area) in Figure

), who was about 60 years old at the time of recording, is a male native of the Jianchuan region, originating from QiÁohǒu, a mountain village some 50 km southwest of Jianchuan city – a remote area known for salt mining and where the language has been less influenced by modern Chinese. These locations are indicated on the map of Yunnan (the southwesternmost province of China in an intensely minority-language-populated area) in Figure