Hawaiian belongs to the Eastern Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family and is indigenous to the islands of Hawaiʻi (see Pawley Reference Pawley1966, Marck Reference Marck2000, Wilson Reference Wilson2012). Hawaiian is also an endangered language. Not only was the native population decimated after contact with foreigners and foreign diseases but the language itself came under attack after the occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 (for more on Hawaiian history, see Coffman Reference Coffman2009, Sai Reference Sai2011). Children were thereafter banned from speaking Hawaiian at school and indeed ‘physical punishment for using it could be harsh’ (Native Hawaiian Study Commission 1983: 196). In the decades that followed, Hawaiian was gradually replaced by an English-based creole (HCE or Hawaiʻi Creole English) for practically all Hawaiʻi-born children (Bikerton & Wilson Reference Bickerton, Wilson and Gilbert1987, also Sakoda & Siegel Reference Sakoda and Siegel2003). By the end of the 1970s, most surviving Hawaiian speakers were over 70 years old and fewer than 50 speakers were under the age of 18 (Kawaiʻaeʻa, Housman & Alencastre Reference Kawaiʻaeʻa, Kaluhiokalani (Kaina) Housman and Alencastre2007).

Here we describe the recordings of a 24-year-old speaker of Hawaiian from the town of Hilo on the island of Hawaiʻi who, by his very existence, symbolises the success of the Hawaiian-language revitalisation movement. Established in the 1980s, this movement has resulted in Hawaiian being heralded as a ‘flagship of language recovery’ as well as ‘a model and a symbol of hope to other endangered languages’ (Hinton Reference Hinton2001: 131). The speaker (Hulilau Wilson) is the son of two professors who are also prominent leaders within the Hawaiian language community (William H. Wilson and Kauanoe Kamanā). Professors Wilson and Kamanā each learned Hawaiian as a second language (L2), having grown up speaking General American English and HCE, respectively. Their son's first language (L1) was Hawaiian, which he learned at home and through a progression of Hawaiian-language immersion schools (where he and the author were classmates) (see e.g. Wilson Reference Wilson1998, Reference Wilson and May1999; Warner Reference Warner2001; Wilson & Kamanā Reference Wilson and Kamanā2001, Reference Wilson and Kamanā2006). By high school the speaker could also converse in HCE and English and remains fluent in all three languages today. Recordings from a second male (the author, ʻŌ) have been included to supplement the primary recordings by the speaker (H).

The dialect described here may be called standard Hawaiian and is generally used wherever Hawaiian is spoken across the islands.Footnote 1 It is also broadly represented by both the standard Hawaiian grammar (Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979) and dictionary (Pukui & Elbert Reference Pukui and Elbert1986). The recordings more specifically describe how this dialect is spoken today by the first generation of speakers to be raised within the Hawaiian language revitalisation movement.Footnote 2

Consonants

The consonant chartFootnote 3 depicts eight contrastive segments which correspond to the following letters of the standardised orthography: ‹h k l m n p w ʻ› (Wilson Reference Wilson1976). The upper-case variants are ‹H K L M N P W› as in English, with the exception that there is no upper-case variant of the letter ‹ʻ›, which in Hawaiian is called an ʻokina. By convention, then, the vowel immediately following an ʻokina is capitalised instead (see the author's first name for an example).

Glottal stops may contrast with the lack of a consonant in an utterance-initial position. Spoken in isolation, a word pair like [ˈʔaka] ʻaka ‘laugh’ and [ˈaka] aka ‘shadow’ can be impressionistically distinguished by the relative abruptness of the vocalic onsets. Word-medially, the contrastive glottal stop tends to be realised as creaky voice. Figure 1 illustrates this for the word /puaʔa/ puaʻa ‘pig’, in which /ʔ/ is shown to be voiced throughout.

Figure 1 Word-medial glottal stop realised as creaky voice.

Polynesian plosives have often been described as unaspirated (e.g. Krupa Reference Krupa1982: 21). Nonetheless we found /p/ and /k/ to be aspirated in the recordings, at least when measured against typical voice onset times (VOTs) in English. To test the received view that /p/ and /k/ are unaspirated in Hawaiian, we therefore formulated a null hypothesis that sample VOTs would not significantly exceed 25 ms, a threshold that would make them aspirated in English (see e.g. Maclagan & King Reference Maclagan and King2007: 92; also Kent & Read Reference Kent and Read1992: 108). Sample VOTs were obtained from the illustrative passage recording (a Hawaiian translation of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’) by manually checking the durations between consonant bursts and voice onsets.

These data show /p/ and /k/ to be aspirated in Hawaiian.Footnote 4 This result raises the question of how to interpret previous claims to the contrary (e.g. Krupa Reference Krupa1982: 21). One conjecture – consistent both with the recordings and with the literature – is that Hawaiian plosives used to be unaspirated but have since become progressively aspirated as a result of contact with English. Indeed, Maclagan & King (Reference Maclagan and King2007, Reference Maclagan, King, Reyhner and Lockard2009) have developed an analogous argument for New Zealand Māori, which is closely related to Hawaiian and shares a similar history of contact with English. A second hypothesis is that aspirated plosives existed as a feature of some older Hawaiian speakers. Some support for this hypothesis comes from Helene Newbrand, who claimed to hear ‘strong aspiration’ on ‘some [k] sounds’ (Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951: 66, 107).

Interestingly, Hawaiian lacks a contrast between [t] and [k], although it does not lack [t] as is sometimes claimed (e.g. Ladefoged Reference Ladefoged2001: 177).Footnote 5 [ˈtapa] and [ˈkapa] refer to the same culturally significant artefact, a type of ‘cloth beaten from the bark of . . . trees’ (Andrews 1865: 260). But both word forms are acceptable and neither is uncommon. We represent the segment as /k/ rather than /t/ since the [k] allophone is more commonly used in the standard dialect.

As Schütz (Reference Schütz1994) explains, both ‹t› and ‹k› appear in early word lists as well as in an earlier version of the orthography, which has suggested a dialectical division between the north-western islands (T-dialects) and south-eastern islands (K-dialects), including the southern and easternmost island of Hawaiʻi, where the speaker comes from. In the 1820s, a group of Congregational missionaries from New England voted on which of the ‘superfluous’ consonants to expunge from Hawaiian (see Schütz Reference Schütz1994). In addition to ‹t› and ‹k›, the missionaries found that the letters ‹p› and ‹b› could also be supplemented for each other; as could ‹w› and ‹v›. The letters ‹d›, ‹r›, and ‹l› could all three be interchanged freely. Despite some debate among the missionaries (depending on where in the islands they were based), the final vote resulted in the exclusion of all but one letter in each set – the winners being ‹k›, ‹p›, ‹w›, and ‹l›. It is somewhat arbitrary, then, that the orthography retained ‹k› rather than ‹t›. The missionary vote may, however, explain the confusion over the mistaken ‘lack of [t]’ in Hawaiian.

Hawaiian does not contrast [w] and [v] either (see Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979: 12). Some authors have distinguished a third allophonic variant of [w] and [v] – i.e. a ‘soft v’ or labio-dental approximate [ʋ] (see Wilson Reference Wilson1976: Section 4). Schütz (Reference Schütz1981) hypothesised that the letters ‹w› and ‹v› were failed attempts to approximate an intermediate sound when Hawaiian was first transcribed. Since the missionary vote, however, only ‹w› is written. While some attempts have been made to distinguish a continuum of W- and V-dialects from one end of the Hawaiian archipelago to the other (e.g. Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951: 128–131; Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979), these attempts have been confounded by the existence across all documented dialects of a phonetic [w]-glide (see Wilson Reference Wilson1976: Section 3; Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010: 70–71). We represent the segment here as /v/, in contrast to the orthography, because we only found instances of the [v]-allophone in the recordings. The variety of Hawaiian spoken on the island of Hawaiʻi is usually identified as either a V- or a mixed W-V dialect (e.g. Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951; Wilson Reference Wilson1976: Section 4; Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979).

The nasals /m/ and /n/ are distinguished by place of articulation. In the literature, /n/ has sometimes been described as a dental [![]() ] (Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951, Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979). The speaker did report producing /n/ at the alveolar ridge when pressed. But this would be better studied experimentally, perhaps using palatography. Like aspiration in plosives, as well as other dialectical features in Hawaiian, the articulation of /n/ may have changed over time because of contact with English, change within Hawaiian, or both (see Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951: 44–50).

] (Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951, Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979). The speaker did report producing /n/ at the alveolar ridge when pressed. But this would be better studied experimentally, perhaps using palatography. Like aspiration in plosives, as well as other dialectical features in Hawaiian, the articulation of /n/ may have changed over time because of contact with English, change within Hawaiian, or both (see Newbrand Reference Newbrand1951: 44–50).

Newbrand (Reference Newbrand1951: 8) claimed that /l/ alternates freely between clear and velarised pronunciations, although it sounds relatively clear in the recordings. While more prominent on other islands (Wilson Reference Wilson1976: Section 4), the alternative realisation of /l/ as a tap [ɾ] may explain the early spelling variants ‹d› and ‹r›.

Given such a relatively small set of contrastive consonants, foreign words may be stretched to fit into the native Hawaiian system. At the same time, foreign borrowings also motivate a division within the Hawaiian lexicon.

On the one hand, loanword adaptation describes the changes made when words are borrowed from one language to another, including mappings between segmental inventories. One mapping, from the English consonants [t d θ ð s ʃ z ʒ tʃ dʒ k ɡ] to Hawaiian /k/, stands out in particular for its lopsidedness (e.g. Carr Reference Carr and Fischel1951; Pukui & Elbert Reference Pukui and Elbert1957: xvii; Schütz Reference Schütz1994: 192; Adler Reference Adler2006; Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009).

Lexical stratification, on the other hand, describes the partition of a language's words into distinct sets – often as the result of contact with other languages (Saciuk Reference Saciuk1969, Itô & Mester Reference Itô, Mester and Goldsmith1994). Unlike loanword adaptation, this is an example of the language system changing in response to borrowings. In this sense, lexical stratification should not be confused with the ‘affixation levels’ of Lexical Phonology (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky and Yang1982). As an illustration, consider the following loanwords from the Kōmike Huaʻōlelo (Reference Huaʻōlelo2003).

Consonants (foreign)

As the recordings show, these words are not just written with foreign letters – they are also pronounced with foreign sounds that are absent from the native consonant chart above. One way to account for these sounds in the recordings, and in Hawaiian more generally, is to divide the Hawaiian lexicon into core and peripheral strata, which represent native words and foreign words respectively. The following loanwords from English ‒ [pea] pea ‘pear’, [bea] pea ‘bear’, and [fea] fea ‘fair’ ‒ might therefore contrast meaningfully in the peripheral stratum, but collapse into a single form within the core stratum via loanword adaptation, formally as in /pea/ ‘pear, bear, fair’.Footnote 6

Vowels

Short vowels

Short vs. long vowels

‘Short’ diphthongs

‘Long’ diphthongs

Analyses of the Hawaiian vowel system today owe an enormous debt to Schütz Reference Schütz1981 (see e.g. Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2005, Rehg Reference Rehg, Siegel, Lynch and Eades2007, Donaghy Reference Donaghy2011 via Schütz Reference Schütz, Bowden, Himmelmann and Ross2010). Schütz (Reference Schütz1981) distinguished five short and five long vowels. In this Illustration we represent the vowels as /i e a o u/ and /iː eː aː oː uː/.Footnote 7

Using the data in the illustrative passage as a small spoken corpus, we found that all short-vowel pairs contrasted with each other in F2 (degree of tongue advancement) with the exception of the back vowels, /o/ and /u/, which differed only in F1 (tongue height). Three vowel pairs did not differ in F1 (height). These were the high vowels (/i/ and /u/), the mid vowels (/e/ and /o/), and /i/ and /e/. All other vowels were found to differ in both F1 and F2.Footnote 8 See Figure 2 for a visualisation of the data and Figure 3 for a schematic of the vowel system.

Figure 2 Short vowels in log-format space, taken from the recorded passage.

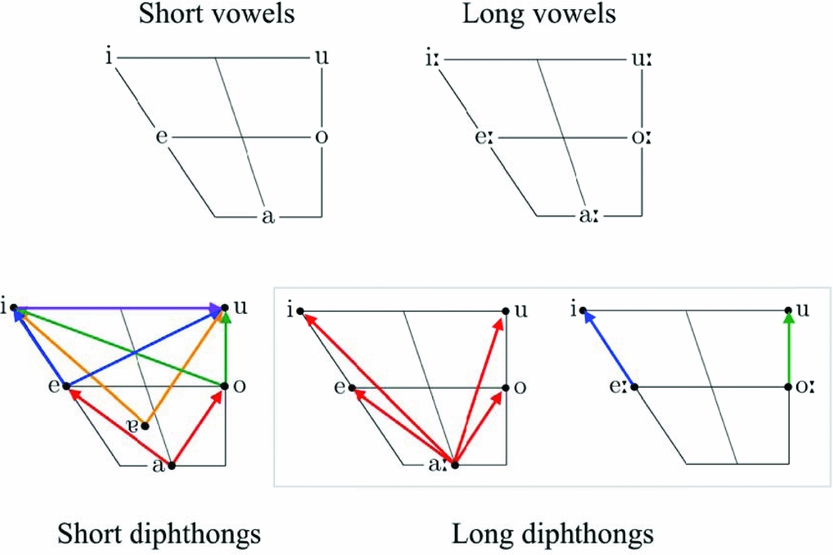

Figure 3 Pseudo-articulatory diagrams for short vowels, long vowels, short diphthongs, and long diphthongs. Arrows in the diphthong charts point from the first to the second articulatory target, and are colour-coded by the first.

Because of insufficient numbers in the sample, it was not possible to compare long vowels with long vowels.Footnote 9 We were, however, able to compare long /aː/ with short /a/. These vowels differed in F1 (height), even when unstressed instances of /a/ were excluded from the analysis, demonstrating that so-called long and short vowels are not simply contrasted by quantity of duration, but also in phonetic quality.Footnote 10 Unstressed tokens of /a/ were excluded to control for a potential confound (Schütz, Kanada & Cook Reference Schütz, Kanada and Cook2005: xiv–xv), which was that, while long vowels are always stressed in Hawaiian, short vowels are only stressed contingently depending on their position in the metrical structure (see ‘Prosody’ section below).

We further tested the prediction that unstressed /a/ would reduce to schwa (e.g. Schütz et al. Reference Schütz, Kanada and Cook2005: xiv–xv) by comparing stressed and unstressed tokens of /a/, but were unable to find a significant difference in F1. An alternative hypothesis was that exemplars of /a/ would be more reduced in high- relative to low-frequency words (e.g. Bybee Reference Bybee2001). To test this we compared measurements from function and content words (high- and low-frequency, respectively), this time finding F1 to differ in the expected direction.Footnote 11 To the best of our knowledge, this represents a new finding in Hawaiian phonetics.

Schütz identified 15 possible diphthongs, in addition to the long and short monophthongs. The diphthongs are qualified as being merely ‘possible’ because ‘some speakers separate the vowels into two syllables’ (Schütz et al. Reference Schütz, Kanada and Cook2005: xiv). For a long time there was no good way to predict how likely any sequence of vowels was to constitute either a single diphthong or a pair of syllables. But diphthongs can now be predicted using statistical models of syllabification which have been trained on Hawaiian corpora (Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010).

Hawaiian diphthongs subdivide into so-called ‘short diphthongs’ (short vowel + short vowel) and ‘long diphthongs’ (long vowel + short vowel). Unlike English, but like many other languages including Māori (see e.g. Harlow Reference Harlow2007), diphthongs in Hawaiian are not ‘unit phonemes’ (Rehg Reference Rehg, Siegel, Lynch and Eades2007). If we assumed that Hawaiian diphthongs were ‘unit phonemes’, and therefore indivisible, we would not expect words like hei ‘snare’ to produce partial reduplications like hehei ‘to entangle’ (Rehg Reference Rehg, Siegel, Lynch and Eades2007: 127).Footnote 12 Examples like these led Rehg to analyse Hawaiian diphthongs as complex constituents containing distinct units at a segmental level.

In practice, vowel pairs can be identified as diphthongs by looking for violations in the stress rules (Schütz Reference Schütz1981; see also Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010: 81–84). These state that stress is typically perceived on a penultimate short vowel as in [liˈona] liona ‘lion’. A word like [ˈloina] loina ‘custom’ violates this rule and motivates the analysis of /oi/ as a diphthong. The sequence /io/, by contrast, is classified as two consecutive syllables, /i/ and /o/. Diphthongs are heavy syllables and, in Hawaiian, heavy syllables always receive stress on their first vowel (see ‘Prosody’ section).

A similar line of reasoning implies that /oe/ is not a diphthong since [moˈena] moena ‘mat’ has penultimate stress in the recordings (also see Pukui & Elbert Reference Pukui and Elbert1986). It has been observed, however, that speakers produce this word as [ˈmoena] ‘mat’ in another Hawaiian dialect (Larry Kimura, personal communication). Whether a sequence like /oe/ is counted as a diphthong may therefore depend on social factors. More work will be needed to explore these fascinating dialectical differences.

Because it has been reported that /ai/ and /ae/ can be distinguished by their realisations of /a/ (Schütz et al. Reference Schütz, Kanada and Cook2005: xiv–xv), we examined these diphthongs in our spoken corpus. The results showed the realisation of /a/ to be higher before /i/ than it is before /e/, which is consistent with pre-assimilation to a height feature. We note that /i/ and /e/ differed both in F1 and F2 in the diphthongs.Footnote 13

Prosody

There is an outdated view that Hawaiian phonology includes not only a sparse system of eight consonants and five vowels, which we have argued against above, but as Schütz (Reference Schütz1981: 2) observed (in order to refute) also ‘a closed list of forty-five simple syllables (either V or CV), occurring in any order, and then accented in a regular way’. The template for Hawaiian syllables might instead be described as (C)V1(V2), where V is either a long or short vowel (10 total) and where the possible V1 + V2 sequences are constrained to yield exactly the set of acceptable diphthongs detailed in the previous section (see Schütz Reference Schütz1981, also Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2005, Reference Parker Jones2010). Although the orthographic digraphs ‹Kr›, ‹st›, and ‹ch› provide potential counterexamples (suggesting CC-clusters), they only occur in loanwords like [k![]() istʷo] Kristo ‘Christ’ (< Greek Χριστός) and [moːtʃiː] mōchī ‘mochi’Footnote 14 (< Japanese 餅) (see Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009). It is unclear, then, whether these digraphs should be represented as clusters (CC) or singletons (C). Borrowings from biblical languages, including Greek, are outliers as well for being deliberately loaned by English-speaking missionaries.

istʷo] Kristo ‘Christ’ (< Greek Χριστός) and [moːtʃiː] mōchī ‘mochi’Footnote 14 (< Japanese 餅) (see Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009). It is unclear, then, whether these digraphs should be represented as clusters (CC) or singletons (C). Borrowings from biblical languages, including Greek, are outliers as well for being deliberately loaned by English-speaking missionaries.

The phonology of Hawaiian is weight-sensitive (Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2005, Reference Parker Jones2010). Syllables containing a long vowel or a diphthong (or both) are ‘heavy’ and all heavy syllables are stressed, whereas syllables containing a single short vowel are ‘light’ and may or may not be stressed, depending on metrical position (Hyman Reference Hyman1985, Hayes Reference Hayes1989). However, it is descriptively inadequate to describe Hawaiian stress as being assigned with regular right-to-left trochees (refer to the Fijian analysis in Hayes Reference Hayes1995). While such a regular pattern works for some words, like /ma.ˈku.a.ˈhi.ne/ makuahine ‘mother’, it fails for other words, like /ˈʔe.le.ma.ˈku.le/ ʻelemakule ‘old man’ (Schütz Reference Schütz1978, Reference Schütz1981).Footnote 15 Hayes (Reference Hayes1995) met a similar pattern in his metrical analysis of Fijian, where one pattern was much less common than the other and could, with relative economy, be lexicalised. But this is not the case in Hawaiian, where, at least in the case of five-syllable words like those above, almost half of the vocabulary uses the ‘mother’ pattern while the other half uses the ‘old man’ pattern (Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2005, Reference Parker Jones2010). Any attempt to lexicalise one pattern would therefore require lexicalising half of the words. Although this has led Schütz (Reference Schütz1981) and Schütz et al. (Reference Schütz, Kanada and Cook2005) to claim that Hawaiian stress is ‘unpredictable’, recent work has shown that stress can be predicted accurately for 96% of the native vocabulary through the use of machine learning (Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010).

More work is still needed on other areas of Hawaiian prosody, such as intonation. A systematic ToBI-like analysis would be very useful (see the chapters in Jun Reference Jun2005, for example extensions of the ToBI system to new languages; also see Murphy Reference Murphy2013).

Conventions

Wilson (Reference Wilson1976) has produced a detailed list of conventions for converting the standard Hawaiian orthography (effectively phonemic transcriptions) into more phonetic transcriptions, representing the standard dialect or dialectical variants. Many of these rules have been implemented as finite-state transducers (Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010), which for example made it possible to convert from orthographic to allophonic representations automatically in the illustrated passage.

A few conventions stand out in the passage. First, before round vowels consonants appear labial. Second, after nasal consonants vowels appear nasalised. An example of each can be found in the word [ˈlʷoinã] loina ‘custom’ (note the labialised /l/ and nasalised /a/). Hawaiian also has two phonetic glides that sometimes appear, presumably due to co-articulations. One glide, [j], occurs either between /i/ and /a/ or between /e/ and /a/ (as in mea [meja] ‘thing’), whereas the other glide, [w], occurs between /o/ or /u/ and another vowel (as in nui [nuwi] ‘big’) (Wilson Reference Wilson1976, Elbert & Pukui Reference Elbert and Pukui1979). These glides may be summarised in the following re-write rules, where ε represents the empty string and V stands for any short or long vowel (see Parker Jones Reference Parker Jones2010):

ε → j / {i, e} __ a

ε → w / {o, u} __ V

In older sources, the [w]-glide has sometimes been confused with the [w]-allophone that belongs to contrastive /v/. For example Pukui & Elbert (Reference Pukui and Elbert1986) recorded two spellings for ‘old woman’, luahine and luwahine, where the spelling includes an unexpected ‹w›. One never pronounces the [v] allophone in this word (Wilson Reference Wilson1976). Since the allophones [v] and [w] vary freely, we reason that the [w] in the variant spelling of ‘old woman’ is in fact a glide and not a contrastive segment. The segmental representation should therefore be /luahine/ and not */luvahine/. We note that similar reasoning generalises to other cases of ambiguous [w].

Phrase-final conventions have been observed in Hawaiian: phrase-final long vowels shorten and phrase-final short vowels devoice (Wilson Reference Wilson1976). But more work in this area is needed.

To conclude, this phonetic illustration has touched on sound changes over time, dialectical differences, infrequent sounds (like the long vowels), intonation, and pronunciation conventions in Hawaiian. Future studies might interestingly expand on stylistic differences in Hawaiian such as the optional deletion of /a/ (e.g. puʻa for puaʻa ‘pig’) (Wilson Reference Wilson1976) or the contexts in which an allophone like [t] might be preferred. However, the most useful contribution right now would be the creation of shared resources such as a spoken corpus of Hawaiian. A spoken corpus would be a valuable tool for Hawaiian researchers and learners; it would also be a powerful symbol of Hawaiian's continued revitalisation and growth.

Recorded passage in transcription

The illustrative passage is a Hawaiian translation of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’. It has been rendered orthographically and in broader and narrower allophonic forms, where the narrower transcription applies the conventions discussed above. In addition, the realisation of /a/ differs when preceding either a mid or high vowel in a diphthong or when appearing as a monophthong in function or content words.

Orthographic version

I ka hoʻopaʻapaʻa ʻana o ka Makani ʻĀkau me ka Lā ʻo wai ka mea o lāua i ʻoi aku ka ikaika, māʻalo maila he kanaka hele i kīpuni ʻia i ke koloka mehana. Ua ʻae like lāua ʻo ka mea o lāua e hana aku a wehe ke kanaka i kona koloka, ʻo ia ka ikaika loa. Hao ʻino akula ka Makani ʻĀkau me kona ikaika a pau loa, e like naʻe me ka nui o kona hao ʻana, pēlā ka nui o ko ke kanaka kīpuni paʻa ʻana mai i kona koloka; a hoʻokuʻu akula ka Makani ʻĀkau i ka pahuʻa o kāna hana. Pā mehana maila ka Lā, a ʻo ka wehe koke akula nō ia o ke kanaka i kona koloka. Pēlā i pono ai ko ka Makani ʻĀkau ʻae ʻana ē ʻo ka Lā ka ikaika loa o lāua.

Allophonic versions

Broader

i ka hoʔopaʔapaʔa ʔana o ka makani ʔaːkau me ka laː ʔo vai ka mea o laːua i ʔoi aku ka ikaika maːʔalo maila he kanaka hele i kiːpuni ʔia i ke koloka mehana ‖ ua ʔae like laːua ʔo ka mea o laːua e hana aku a vehe ke kanaka i kona koloka ʔo ia ka ikaika loa ‖ hao ʔino akula ka makani ʔaːkau me kona ikaika a pau loa e like naʔe me ka nui o kona hao ʔana peːlaː ka nui o ko ke kanaka kiːpuni paʔa ʔana mai i kona koloka a hoʔokuʔu akula ka makani ʔaːkau i ka pahuʔa o kaːna hana ‖ paː mehana maila ka laː a ʔo ka vehe koke akula noː ia o ke kanaka i kona koloka ‖ peːlaː i pono ai ko ka makani ʔaːkau ʔae ʔana eː ʔo ka laː ka ikaika loa o laːua ‖

Narrower

Acknowledgements

Mahalo to John Coleman, Albert J. Schütz, ‘Anakala Pila (William H. Wilson), ‘Anakala Lale (Larry Kimura), ‘Anakala Kalena (Kalena Silva), Adrian Simpson, as well as two anonymous reviewers and the copy-editors for comments on earlier drafts. I am grateful to acknowledge a Mellon Fellowship and The Kohala Center for financial support. Mahalo pū i ka mea nona ka leo i hoʻopaʻa ʻia.