Eastern Andalusian Spanish (henceforth EAS), is spoken in the east of Andalusia, the southernmost autonomous region of Spain. EAS is most similar to Western Andalusian Spanish (WAS) and to Murcian Spanish, the latter spoken in the autonomous region of Murcia, immediately to the east of Andalusia, and it shares some phonetic traits with EAS, such as vowel lowering. Geographically, Eastern Andalusia includes the provinces of Almería, Granada, Jaén and Málaga, although the precise linguistic delimitation of this area is somewhat more complicated (Figure 1). The main criterion to differentiate EAS from WAS is the lowering or opening of vowels preceding underlying /s/ (Villena Ponsoda Reference Villena, Andrés, Georg and de Aguilar2000). More detailed information on the differences between EAS and WAS can be found in Jiménez Fernández (Reference Jiménez Fernández1999), Villena Ponsoda (Reference Villena, Andrés, Georg and de Aguilar2000), Moya Corral (Reference Moya and Juan2010) and Valeš (Reference Valeš2014). According to Alvar, Llorente & Salvador (Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973: map 1696), Cádiz and Huelva in the west are the only Andalusian provinces where vowel lowering before underlying /s/ is not found. As the geographical extent of this phenomenon is widely debated, it is difficult to calculate the precise number of speakers of EAS, but we can assert that this geolect is the native variety of Spanish of approximately 2,800,000 speakers if we take into account the figures from the last census of Andalusia in 2011 (Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía 2011).

Figure 1 Distribution of Eastern and Western Andalusian Spanish. Map taken from de Molina Ortés & Hernández-Campoy (Reference de Molina Ortés, Hernández-Campoy and Geeslin2018: 513).

The description and transcription used in this Illustration are based primarily on spontaneous speech samples from 60 male and female speakers from the towns of El Ejido, Balerma and Adra, in the western part of Almería province. Their ages range from 12 years to 78 years and the recordings were taken during informal conversations covering trivial topics such as hobbies. No recordings were taken of speakers from the cities of Almería or Granada, the main urban centers of EAS. The materials were collected during informal interviews between the first author (from the Western Almería sub-region) and the participants, usually at their home. The examples (and associated sound files) we cite are taken from the speech of the first author (33 years of age), from four male speakers (aged 16, 17, 27 and 34 years) and from two female speakers (aged 33 and 43 years). The first transcribed passage in the final section of this Illustration is an extract from a conversation with a 43-year-old woman. The second passage is a reading of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ by the first author. The features found in the recordings match those presented in previous studies on EAS (e.g. Martínez Melgar Reference Martínez Melgar1986, Morris Reference Morris2000 and Peñalver Castillo Reference Peñalver Castillo2006) and are typical of this variety of Spanish. As EAS is spoken across different cities (e.g. Granada, Almería) and rural areas, the sociolinguistic profile of its speakers is very complex. Wulff (Reference Wulff1889), Rodríguez-Castellano (Reference Rodríguez-Castellano1952), Sanders (Reference Sanders1994) and O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2010) have reported a high degree of variability in the use of certain features in EAS, with some authors finding different realizations of one phoneme even within the same town, depending on the sociolinguistic characteristics of the speakers. Melguizo Moreno (Reference Melguizo Moreno2007), for example, found that, in Granada, the use of [ʃ] for /tʃ/ is more common amongst men than women and Tejada Giráldez (Reference Tejada and de la Sierra2012) found that there is a relationship between the variable use of [s], [h] or deletion of /s/ and age in Granada city. Alonso, Zamora Vicente & Canellada de Zamora (Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950) and Martínez Melgar (Reference Martínez Melgar1994) go even further and report variability within the same speaker, with evidence, for example, of free variation of /s/ as [s], [h] or ∅. EAS has been studied extensively since 1881 (Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2017b) and the fact that different authors present different and even conflicting descriptions of the same phenomena adds to the complexity of describing this variety of Spanish (see Sanders Reference Sanders1994, Ruch & Peters Reference Ruch and Peters2016); the biggest controversy is found with respect to the description of EAS vowels and this is explained further below, in the relevant section. More information on the variability of EAS pronunciation across time and space can be found in Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2017b).

For convenience, the word often used in the present account for the tendency not to pronounce codas in their underlying form (which remain evident in standard orthography) will be ‘deletion’. However, as noted by a reviewer, in most cases the underlying consonant can be recovered from the phonetic signal thanks to different elements, such as gemination of following consonants. Traditionally, several authors have referred to this phenomenon as ‘aspiration’ (e.g. Gerfen & Hall Reference Gerfen and Hall2001, Bishop Reference Bishop2007, Ruch & Harrington Reference Ruch and Harrington2014); however, this term is generally avoided here since relatively few examples of so-called aspiration to [h] have been found in the tokens analyzed for the present Illustration. While aspiration and breathy phonation are common in WAS, they are far less common in EAS.

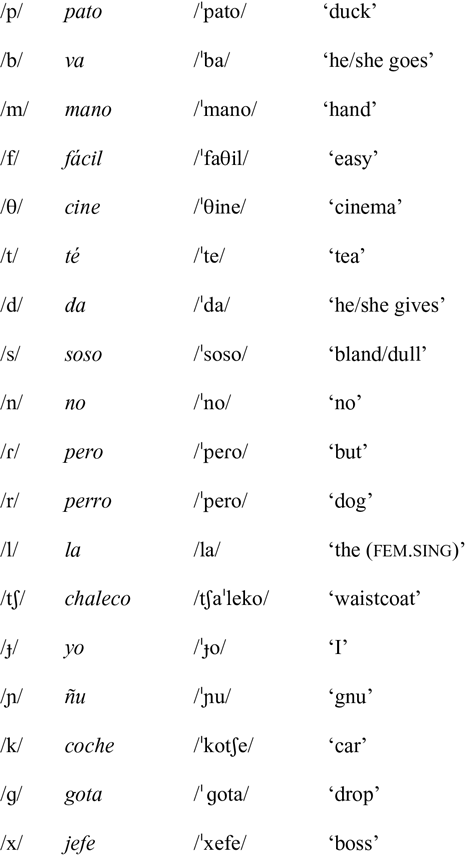

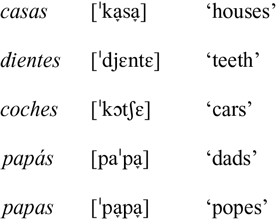

Consonants

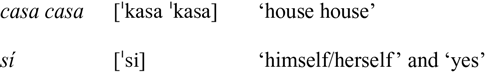

The list below exemplifies each consonant phoneme found in EAS. Allophonic variation, where it occurs, is presented in the discussion that follows. It is worth noting that in any phonetic as opposed to phonemic transcription we use [i e a o u] to represent /i e a o u/, respectively, in all contexts except when these vowels are ostensibly lowered; in those cases, the vowels are transcribed [![]() ɛ

ɛ ![]() ɔ

ɔ ![]() ]. Further details about this process are given in the ‘Vowels’ section.

]. Further details about this process are given in the ‘Vowels’ section.

A few general characteristics of the consonant system of EAS are in order before details of specific consonant phonemes.

Although some differences have been reported between EAS and Castilian Spanish consonants in onset and intervocalic positions, it is in coda position where most differences have been described and analyzed (e.g. Navarro Tomás Reference Navarro Tomás1938, Reference Navarro Tomás1939; Salvador Reference Salvador1957, Reference Salvador1977; Alarcos Llorach Reference Alarcos Llorach1958, Reference Alarcos Llorach1983; López Morales Reference López Morales1984; Gerfen Reference Gerfen2002; Henriksen Reference Henriksen2017). As in other varieties of southern Spanish (WAS and Murcian Spanish), EAS consonants tend to be deleted, reduced or fully assimilated in coda, which has a series of implications for adjacent segments which will be discussed further below.

While complete assimilation of codas in medial position is usual, e.g. hazte [ˈ![]() tːe] ‘to do for/to yourself’ (see also below and in the passages in the final section), full deletion in word-final position is especially common:

tːe] ‘to do for/to yourself’ (see also below and in the passages in the final section), full deletion in word-final position is especially common:

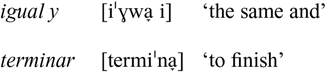

In some circumstances, however, codas can be retained, i.e. especially in careful speech, with /n/ and /l/ being most prone to retention. Coda deletion triggers two main effects: (a) the gemination of the following consonant, even across word boundaries; and (b) lowering of a preceding vowel (discussed in detail in the section below related to vowels):

There is, however, an exception to this pattern. In lower basilects, the final /r/, unlike other consonants, can be deleted from infinitives without lowering the preceding vowel or geminating initial consonant of the enclitic pronoun:

In EAS, consonant gemination (triggered by the deletion or assimilation of a previous consonant always still evident in orthography) can, as some sources have argued, have an apparently contrastive role and is the cue to recognizing an underlying word-medial /s/ (gata ‘she-cat’ [ˈɡata] vs. gasta ‘he/she spends’ [ˈɡ![]() tːa]) (e.g. Gerfen & Hall Reference Gerfen and Hall2001, Gerfen Reference Gerfen2002, Bishop Reference Bishop2007, O’Neill Reference O’Neill2010) (note that we do not provide recordings of examples cited by other authors). Carlson (Reference Carlson2012), however, claims that the distinguishing feature between words like gata ‘she-cat’ and gasta ‘he/she spends’ is vowel lengthening before the underlying /s/.

tːa]) (e.g. Gerfen & Hall Reference Gerfen and Hall2001, Gerfen Reference Gerfen2002, Bishop Reference Bishop2007, O’Neill Reference O’Neill2010) (note that we do not provide recordings of examples cited by other authors). Carlson (Reference Carlson2012), however, claims that the distinguishing feature between words like gata ‘she-cat’ and gasta ‘he/she spends’ is vowel lengthening before the underlying /s/.

Acoustic analysis of plosive gemination shows lengthening of stop closure followed by a burst. Although vowel lowering will be explained in detail in the next section, it is worth noting from the examples below that EAS vowels lower when they precede an underlying consonant that has been deleted or assimilated:

The voiced plosives /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ after a deleted /s/ present an interesting case. In a more emphatic or careful pronunciation, these consonants are pronounced as plosives in codas, although they are much more frequently pronounced as voiced approximants. There seems to be free variation when /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ are geminated, as several examples have been found in our corpus where geminated /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ are pronounced either [bː], [dː] and [ɡː] or [βː], [ðː] and [ɣː], even by the same speaker. Geminated /b/ can also be pronounced [vː] or [fː]:

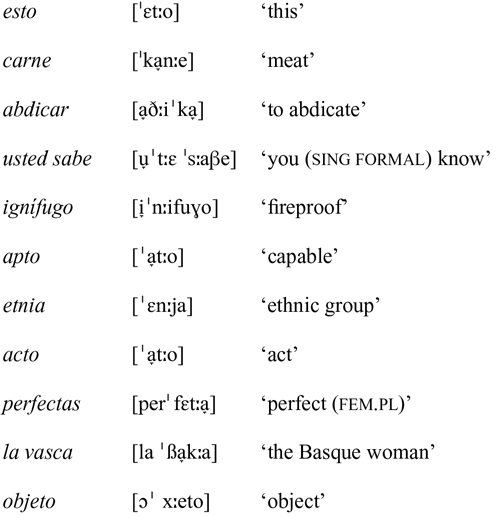

Regarding intervocalic allophones, voiced /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ usually appear as approximants, although fricative articulations, especially of /d/, may also be heard (Table 1).

Table 1 Word-onset and intervocalic voiced plosives in Eastern Andalusian Spanish.

Intervocalic /d/ tends to be deleted when it appears in the last syllable of a word:

For ease of transcription, approximant and fricative realizations of /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ will not be distinguished further here and both will be transcribed as [β], [ð] and [ɣ].

The Andalusian /s/, considered to be stereotypical of Eastern and Western Andalusia, when fully articulated, is reported to be convex in tongue shape (either coronal and flat/convex or pre-dorsal and more convex), as opposed to the concave /s/ in Castilian Spanish (Navarro Tomás, Espinosa & Rodríguez Castellano Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa and Castellano1933). In EAS, the most typical /s/ is alveolar, pre-dorsal and convex (Jiménez Fernández Reference Jiménez Fernández1999: 33) and this consonant can also be pronounced further back in the mouth:

The Spanish phonemes /s/ and /θ/ merge in some varieties of Andalusian Spanish in two different ways: seseo, which is when the phonemes /s/ and /θ/ are pronounced [s] and ceceo, which is when /s/ and /θ/ are pronounced [θ]. Ceceo used to be the norm in the towns of our participants but Navarro Tomás et al. (Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa and Castellano1933) identified a change in progress as they noticed that young speakers in that area were starting to differentiate /s/ and /θ/. This demerger of ceceo in favor of the distinction of /s/ and /θ/ is currently in progress in some locations of Western Andalusia (Regan Reference Regan2017), but this process is much more advanced in Eastern Andalusia. All the participants recorded for the current description maintain the contrast /s/ vs. /θ/ regardless of their level of education; however, we note that this is not the norm across all EAS speaking areas. Furthermore, we also acknowledge the issues and limitations which may arise as a result of comparing studies which were published over six decades apart, as different linguistic changes may have taken place in that time. The following studies are useful nevertheless in terms of highlighting variability regarding seseo and ceceo: Alonso et al. (Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950), for example, reported seseo in Albaicín, a neighbourhood in Granada, Peñalver Castillo (Reference Peñalver Castillo2006) found seseo in Cabra (Córdoba) and García Mouton (Reference García Mouton1992) reported ceceo in the countryside of Jaén, seseo in the capital city of the province albeit with contrast between /s/ and /θ/ in the speech of women and older men.

The same consonants /s/ and /θ/ can also be optionally pronounced [h] in onset and [h] or [ɦ] in intervocalic position, a phenomenon called heheo:

The reduction of /s/ in coda position and more rarely in onset position, has been widely reported to occur in many different varieties of Spanish (e.g. Hammond Reference Hammond and Humberto López1978 in Miami-Cuban Spanish, Figueroa Reference Figueroa2000 in Puerto Rican Spanish, Monroy & Hernández-Campoy Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015 in Murcian Spanish, Henriksen & Harper Reference Henriksen and Harper2016 in south-central Peninsular Spanish). The consonant /s/ can be maintained, debuccalized or deleted to different degrees across EAS and some scholars have also linked different realizations to various sociolinguistic features. Gerfen & Hall (Reference Gerfen and Hall2001) and Bishop (Reference Bishop2007), for example, studied so-called aspiration in EAS and concluded that the aspiration that results from the debuccalization of /s/ is longer than the one that results from debuccalizing /p/ or /k/, so words such as casta [ˈkahtːa] ‘caste’ and capta [ˈkahtːa] ‘he/she captures’ are not fully neutralized in EAS. Even though [h] has been reported as being a realization of coda /s/ in EAS (e.g. Alvar et al. (Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973: map 1696), we have found little evidence of so-called aspiration as a pronunciation of coda /s/ in our corpus.

The realization of plosives after debuccalized /s/ in EAS has also been studied in detail. Torreira (Reference Torreira, Pilar, Joan and María Josep2007) posits that what differentiates minimal pairs like ata [ˈata] ‘he/she ties’ and hasta [ˈ![]() tːa] ‘until’ is post-aspiration of the geminated [t]. He suggests that this also applies to /sk/ and /sp/ and that this is more salient in WAS than in EAS; O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2010) and Ruch & Harrington (Reference Ruch and Harrington2014) reach similar results. Aspiration of voiceless plosives following debuccalized /s/ is less salient in EAS than in WAS but it has been found in our samples:

tːa] ‘until’ is post-aspiration of the geminated [t]. He suggests that this also applies to /sk/ and /sp/ and that this is more salient in WAS than in EAS; O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2010) and Ruch & Harrington (Reference Ruch and Harrington2014) reach similar results. Aspiration of voiceless plosives following debuccalized /s/ is less salient in EAS than in WAS but it has been found in our samples:

In EAS, /n/ and /l/ assimilate to the place of articulation of some consonants even across word boundaries, becoming dental before [t] and [d] and interdental before [θ]; the difference between dental and interdental is not marked in the transcription. The consonants /n/ and /l/ become post-alveolar before [tʃ] and in addition to velar assimilation seen previously in ninguno [niŋˈɡuno] ‘none’, /n/ also becomes labiodental before [f]. This pattern is similar to that found in Castilian Spanish:

It is worth noting that, again for ease of transcription, (inter)dentalized and palatalized allophones of /l/ and /n/ will henceforth be transcribed simply as [l] and [n], respectively.

/n/ may also be fully reduced in EAS in coda. Alonso et al. (Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950) and Zamora Vicente (Reference Zamora Vicente1960: 324) explain that when this occurs, the nasality is retained on the preceding vowel to maintain the semantic meaning associated with a deleted /n/. According to these authors, viene [ˈbjene] ‘s/he comes’ and vienen [ˈbjenḛ] ‘they come’ are distinguished by the nasality found in the final vowel of the latter form. Other examples of /n/ deletion and vowel nasalization include:

This can also happen in word-medial codas, but to a much lesser degree:

We can in fact think of /n/ deletion as being involved in a two-step process. The first step is when /n/ is deleted and the previous vowel is left nasalized. The second step would be vowel denasalization, which is also possible in some cases, but is much less frequent:

When retained, however, word-final coda /n/ is usually pronounced [ŋ] in EAS, as in WAS:

While the lateral /l/ is also deleted at a higher rate in word-final codas than word-medially, as in Murcian Spanish (Monroy & Hernández-Campoy Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015), coda /l/ is also frequently rhotacized when the following syllable onset is a consonant:

In EAS, as in most other varieties of Spanish, /r/ is found word-initially and in intervocalic position, as well as after /n/, /l/ and /s/, while /ɾ/ is found intervocalically and in the following sequences /pɾ bɾ tɾ dɾ kɾ ɡɾ fɾ/. The rhotics /r/ and /ɾ/ are only contrasted in intervocalic position in EAS, as /ɾ/ does not appear word-initially and the opposition /ɾ/ vs. /r/ is neutralized in coda position, even when EAS speakers maintain the coda consonant instead of deleting it, which can happen in more formal situational contexts. Following Monroy & Hernández-Campoy (Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015), we transcribe coda tap and trill phonemically as /r/. These two rhotics are also merged in syllable-final position in Castilian Spanish, even though this variety of Spanish does not reduce coda consonants in the manner found in EAS. In EAS, as in Castilian Spanish, coda rhotics present a continuum of realizations from tap to trill which depend on stylistic and dialectical variation (e.g. Blecua Falgueras Reference Blecua Falgueras, María José, Margarita, Celia Casado, María Victoria, Manuel, José Manuel, Pilar García, Lourdes García-Macho and Victoria Marrero2005, Bradley Reference Bradley2014). The coda rhotic is the only consonant which shows a different pattern of deletion word-finally and word-internally in EAS. Although it can be maintained in emphatic or in more careful speech, this rhotic is generally deleted word-finally in everyday conversation:

As is the case when any consonant is deleted, word-final /r/ deletion triggers lowering of the previous vowel (explained in more detail in the vowel section) and gemination of the following consonant due to complete assimilation of /r/; the latter also occurs across word-boundary:

In word-medial codas, the rhotic is normally fully assimilated to the following consonant only when it precedes /n/ or /l/ (e.ɡ. perla [ˈpɛlːa] ‘pearl’, tierno [ˈtjɛnːo] ‘tender’) or in infinitives preceding an enclitic pronoun starting with /m/, /l/ or /n/, e.g. comerlo [koˈmɛlːo] ‘eat it’; if this happens, /m/, /n/ or /l/ are geminated. The rhotic can, however, be maintained in word-medial codas involving /l n/ in careful speech:

The reduction of /tʃ/ to [ʃ], mentioned in the introduction as occurring in Granada EAS, is not found in the EAS variety spoken in Almería and described here.

EAS palatal plosive /ɟ/ can also surface as [j] in intervocalic position. Monroy & Hernández-Campoy (Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015) describe a similar process for Murcian Spanish and review various descriptions of this consonant. Some authors, however, have argued for a palatal affricate phoneme or fricative in Castilian Spanish (e.g. Martínez Celdrán, Fernández Planas & Carrera Sabaté Reference Martínez Celdrán, Planas and Sabaté2003).

It is worth noting that due to a reduction process called yeísmo, /ʎ/ (spelt ll in Spanish) has merged with /ɟ/ (spelt y) in most parts of the Hispanic world, even in most phonologically conservative varieties of Spanish. None of the participants in our study differentiated /ɟ/ and /ʎ/, so /ʎ/ will not be included in our analysis. However, in the older literature some authors have reported that the opposition /ɟ/ and /ʎ/ is maintained in some areas where EAS is spoken: Salvador (Reference Salvador1957) found the distinction /ɟ/ – /ʎ/ in the speech of women over 70 years of age whom he had interviewed in Cúllar-Baza (Granada), although younger people in this town no longer maintained it; Alvar (Reference Alvar1955a) and Llorente (Reference Llorente1962) reported the opposition /ɟ/ – /ʎ/ in the northeast of Granada province; Zamora Vicente (Reference Zamora Vicente1960: 311) found the same in parts of the province of Granada and Jaén; finally, Zamora Vicente (Reference Zamora Vicente1960: 312) claimed that the distinction /ɟ/ – /ʎ/ was maintained in some areas by women. To our knowledge, no recent study has analyzed the opposition /ɟ/ – /ʎ/ in EAS.

The velar fricative /x/ presents some variability in EAS, both word-initially and word-medially, as well as geographically – something that is evident when comparing earlier discussion on EAS since the late nineteenth century. Some areas present some local variability and it is possible to find variation even within the same speaker. Rodríguez-Castellano & Palacio (Reference Rodríguez-Castellano and Palacio1948a, b) found that /x/ was pronounced [h] in a town they studied in Granada. Wulff (Reference Wulff1889), Salvador (Reference Salvador1957) and Peñalver Castillo (Reference Peñalver Castillo2006) also found that [h] was the preferred pronunciation of /x/ in EAS; however, Peñalver Castillo (Reference Peñalver Castillo2006) reported breathy voiced [ɦ] at times in intervocalic position and after voiced consonants and [x] in speakers of a medium or high education level. The most complete study of this phenomenon can be found in Alvar et al. (Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973: map 1716). According to these authors, /x/ is pronounced [h] in the west of the province of Granada, in the south of Jaén province and to the east of Málaga province, while it is pronounced [x] in central and eastern Almería and in central and northern Granada. Interestingly, Alvar et al. (Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973: map 1716) present Western Almería, the area where all the participants analyzed for the present study are from, as having /x/ pronounced as either [h] or [ɦ]; the same map presents the area immediately to its east as pronouncing /x/ as [x]. This border must have moved towards the west since Alvar et al. (Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973) was published as the most frequent option found in the speakers analyzed in the present study is to pronounce /x/ as [x], alongside [h]. No studies have reported any link between word-initial or word-medial position and a preference for [x] and [h].

Some scholars since the time of Wulff (Reference Wulff1889) have also reported variable intervocalic voicing of voiceless consonants in EAS. O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2010), for instance, found that, in his sample, Andalusian intervocalic voiceless plosives were voiced in 69% of cases; intervocalic consonant voicing has also been reported in other varieties of Spanish (e.g. Trujillo Reference Trujillo1980). The voicing of /p t k/ can create potential mergers with /b d ɡ/, respectively, and O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2010) reports that this happens in intervocalic position in Andalusian Spanish in 12.5% of cases in his corpus; however, he does not give specific figures for EAS. Further information on the phonological recategorization which might be at play here can be found in studies of non-Andalusian Spanish by Torreira & Ernestus (Reference Torreira and Ernestus2011), Hualde, Simonet & Nadeu (Reference Hualde, Simonet and Nadeu2011) and Nadeu & Hualde (Reference Nadeu and Hualde2015). Examples of voicing of obstruents in our sample include:

Vowels

Monophthongs

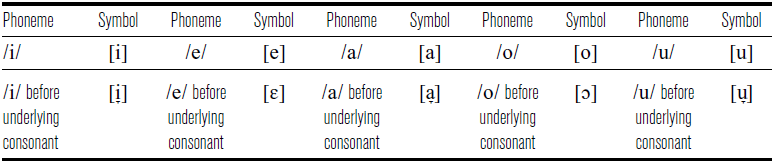

In EAS, it is important to differentiate between vowels that do not precede an underlying consonant and vowels that do (e.g. Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2017c, Reference Herrero de Haro2018, Reference Herrero de Haro2019a).

The EAS vowel system is subject to the already noted and much debated process of ‘vowel opening’. Following a reviewer’s recommendation, this phenomenon will henceforth be referred to as vowel lowering, although it is worth bearing in mind that vowel lowering may also be accompanied by an F2 movement. Given the significant level of disagreement among researchers on Eastern Andalusian Spanish regarding its phonological nature, the extent to which different vowels participate in vowel lowering, as well as which underlying consonants are involved, it is necessary to provide an account of this debate before moving on to a phonetic description of vowel lowering in our own data (see Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2017b for a detailed overview).

Navarro Tomás (Reference Navarro Tomás1938, Reference Navarro Tomás1939) posited that when /s/ was aspirated, i.e. debuccalized, in coda position, a preceding /e/, /a/ or /o/ became lower, with the so-called aspiration being lost in some cases. According to the same author and others, e.g. Salvador (Reference Salvador1977), vowel lowering obtains phonemic value when aspiration is lost, as this differentiates pairs of words such as la ‘the (fem.sing)’ and las ‘the (fem.pl)’. It should be noted, however, that some authors believe that /a/ closes before a deleted coda (e.g. Hernández-Campoy & Trudgill Reference Hernández-Campoy and Trudgill2002). Furthermore, other authors, such as Mondéjar Cumpián (Reference Mondéjar Cumpián1979) and López Morales (Reference López Morales1984), believe that vowel lowering is a phonetic process with no phonological value.

While all sources on vowel lowering in EAS agree that mid and low vowels /e a o/ are affected by this reduction of /s/, opinions significantly vary as to whether high vowels /i u/ also participate. The claim by Navarro Tomás (Reference Navarro Tomás1938, Reference Navarro Tomás1939) and Sanders (Reference Sanders1998), for instance, that only /e/, /a/ and /o/ open but not /i u/ before underlying /s/ is supported by a recent experimental study conducted by Henriksen (Reference Henriksen2017) on speakers from Granada. However, there is also a body of research of more than twenty studies that reports the lowering of /i/ and /u/ before a deleted /s/ (e.g. Rodríguez-Castellano & Palacio Reference Rodríguez-Castellano and Palacio1948a; Alvar Reference Alvar1955a, b; Alvar et al. Reference Alvar, Llorente and Salvador1973; Gómez Asensio Reference Gómez and José1977; Martínez Melgar Reference Martínez Melgar1986, Reference Martínez Melgar1994; Peñalver Castillo Reference Peñalver Castillo2006; Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2019a, b, c). Even some studies that do not fully support opening of /i/ and /u/ report evidence of some lowering; for example, Salvador (Reference Salvador1977) finds lowering of /i/ but not of /u/, while Sanders (Reference Sanders1994) reports a very slight opening of /i/ and /u/ preceding deleted /s/ and Sanders (Reference Sanders1998) finds lowering of pretonic /u/ and a very slight opening of pre-tonic /i/ before deleted /s/. It is worth noting that Zubizarreta (Reference Zubizarreta1979), López Morales (Reference López Morales1984) and Martínez Melgar (Reference Martínez Melgar1986) support the opening of /i/ and /u/ but they consider this phonetic, not phonemic.

The question of which deleted consonants trigger vowel lowering is also the subject of ongoing debate and research. Eighteen studies have found different degrees of vowel lowering depending on what the following underlying consonant is (e.g. Wulff Reference Wulff1889; Navarro Tomás Reference Navarro Tomás1938, Reference Navarro Tomás1939; Alonso Reference Alonso1956; Gómez Asensio Reference Gómez and José1977; García Marcos Reference García Marcos1987; García Mouton Reference García Mouton1992; Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2016, Reference Herrero de Haro2017a, c, Reference Herrero de Haro2019a, b, c). Rodríguez-Castellano & Palacio (Reference Rodríguez-Castellano and Palacio1948a), for instance, claim that /a/ opens to different degrees depending on whether the following deleted consonant is /s/, /θ/ or /d/ and, for Alonso et al. (Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950), /a/ has a different quality before deleted /s/, /r/ and /l/. Alonso (Reference Alonso1956) found that final /as/, /al/ and /ar/ were pronounced [e̞] in some some towns in the west of Eastern Andalusia but this phenomenon does not appear in our samples. Finally, according to Mondéjar Cumpián (Reference Mondéjar Cumpián1979), all vowels open before deleted /s x θ r l/.

Studies such as Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2016, Reference Herrero de Haro2017a, c) have examined whether that expanded type of vowel lowering has phonemic value, although we make no definitive claims about this here noting only that further investigation, including in terms of phonological patterning, is required.

Perception tests carried out in Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2016, Reference Herrero de Haro2017a) seem to indicate that, at least in the cases of /e/ and /o/, the lowering that these vowels undergo preceding deletion of final /s r θ/ may be what provides the cue to these listeners that a consonant segment is missing, thus helping them infer the meaning of the word heard. It could be argued that final-consonant deletion may be incomplete, so that, in the articulation, some kind of reduced consonantal gesture remains; however, no indication or remnant of consonantal gestures has been found in the samples used for the acoustic analysis. That said, investigation is still needed to ascertain that the identification is not based on undetected suprasegmental features (e.g. duration, pitch, intensity); a possible relation between identification and any formant slope (transition), and not only formant values, as studied in Kewley-Port & Goodman (Reference Kewley-Port and Goodman2005), should also be investigated but this falls outside the remit of the present description.

The divergence of viewpoints and results between the studies with respect to vowel lowering in EAS may be accounted by the differing effect of a range of factors. For example, many researchers point out to a great deal of sociolinguistic variation in EAS pronunciation (e.g. Wulff Reference Wulff1889, Navarro Tomás Reference Navarro Tomás1939, Peñalver Castillo Reference Peñalver Castillo2006, Tejada Giráldez Reference Tejada and de la Sierra2012) and some researchers have analyzed read speech while others have examined spontaneous speech. Likewise, most articles focus on Granada (136 km from Western Almería), some on Jaén (225 km from Western Almería) and some on Córdoba (332 km from Western Almería) and this geographical differentiation could also explain differences between previous research and ours; as with any other language variety, EAS varies through space and, therefore, it is normal to find some variation between towns located over 200 or 300 km from each other. Finally, different researchers work with different sample sizes and this could have influenced results. For example Sanders (Reference Sanders1994) analyzed the speech of three male speakers from villages near Granada city while the present corpus has been taken from the speech of 60 speakers from Western Almería. The fact that so many researchers have reported /i/ and /u/ lowering in EAS makes the issue of statistical power less likely; however, it should be clear from these paragraphs that there is no consensus regarding EAS vowels at this point and that further research is required since this issue is still not settled.

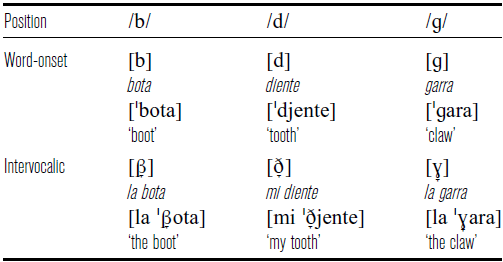

The vowel data presented in the current description come from a corpus of 1913 stressed and unstressed vowels taken from a corpus collected by the first author and already partly analyzed (e.g. Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2016, Reference Herrero de Haro2017a). The analysis of our data shows not only that the five basic Spanish vowels (/i e a o u/) open when they precede an underlying /s/, but it suggests also that the deletion of /r/ and of /θ/ changes the quality of the vowels to a different degree than with /s/ deletion. As Figure 2 shows below, lowering is more evident in non-high vowels, especially /e o/, which could explain in part why /i/ and /u/ lowering is reported less frequently in the literature; a detailed breakdown of the statistical significance for each of these realizations can be found in Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2019c). The greatest degree of lowering seen in Figure 2 appears to be associated mostly with a following coda /r/, with post-sibilant lowering more moderate in degree. Lowering before /θ/ appears also to involve more fronting of high vowels and backing of non-high vowels. It should be noted that Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2016, Reference Herrero de Haro2017a, c, Reference Herrero de Haro2019a, b, c) are the only studies that have analyzed vowel lowering specifically before /r/ or /θ/ (rather than just /s/) acoustically, perceptually and/or statistically (for a detailed account of EAS vowel descriptions in studies published between 1881 and 2016, see Herrero de Haro Reference Herrero de Haro2017b).

Figure 2 Distribution of Eastern Andalusian Spanish vowels (average values based on 1913 stressed and unstressed tokens, 60 subjects).

Table 2 Proposed symbols to transcribe Eastern Andalusian Spanish vowels.

The type of vowel lowering shown in Figure 2 is also included in our description and transcription but no distinction is made in the transcriptions regarding whether a lowered vowel precedes an underlying /s/ or an underlying /r/ or /θ/. The list of words included in the account of gemination in the Consonants section contains various examples of EAS vowels laxing before different underlying consonants (e.g. /s r p k/); however, these items are not repeated here in the interest of brevity. As noted briefly above, we propose the phonetic symbols in Table 2 to transcribe EAS vowels and EAS vowels preceding underlying consonants. It is important to note that we do not propose different symbols to differentiate between different degrees of vowel lowering depending on what consonant has been deleted (e.g. /e/ before underlying /s/ vs. /e/ before underlying /r/) given the acoustic differences are typically small, as Figure 2 shows.

We believe that the lowering of /i e a o u/ when they precede underlying consonants justify using the symbols [![]() ɛ

ɛ ![]() ɔ

ɔ ![]() ], respectively. Some authors consider /e/ and /o/ higher in EAS than in Castilian Spanish (e.g. Hualde & Sanders Reference Hualde and Sanders1995) but /e/ and /o/ before underlying consonants have already been transcribed as [ɛ] and [ɔ] by other researchers (e.g. Henriksen Reference Henriksen2017). The EAS /a/ is a central vowel. It is more open when it precedes an underlying consonant and that justifies our decision to transcribe lax EAS /a/ as [

], respectively. Some authors consider /e/ and /o/ higher in EAS than in Castilian Spanish (e.g. Hualde & Sanders Reference Hualde and Sanders1995) but /e/ and /o/ before underlying consonants have already been transcribed as [ɛ] and [ɔ] by other researchers (e.g. Henriksen Reference Henriksen2017). The EAS /a/ is a central vowel. It is more open when it precedes an underlying consonant and that justifies our decision to transcribe lax EAS /a/ as [![]() ] when required.

] when required.

Due to vowel harmony, vowel lowering is not restricted to word-final position or to vowels preceding assimilated underlying consonants. The lowering of vowels which precede an underlying word-final consonant spreads leftwards as far as the stressed vowel, as was first identified by Navarro Tomás (Reference Navarro Tomás1938):

Several other authors have also studied this phenomenon and there are different opinions regarding how it works. For Alonso et al. (Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950), features of a vowel only spread across a word to its vowel counterparts (e.g. the first /o/ would open in todos ‘all masculine’ but not in todas ‘all feminine’). Other authors believe that /a/ participates in vowel harmony processes (e.g. Navarro Tomás Reference Navarro Tomás1938), while others believe /a/ does not (e.g. Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1979). Furthermore, Zubizarreta (Reference Zubizarreta1979) believes that /a/ does not let harmony extend beyond it. Optimality Theory has proved useful to analyzing EAS vowel harmony (Jimenez & Lloret Reference Jiménez and Lloret2007 and Lloret & Jimenez Reference Lloret and Jiménez2009) and from a perceptual point of view, the motivation for vowel harmony seems to be to increase the perception of a feature (vowel lowering) by extending it across syllables as much as possible (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2012). Jiménez & Lloret (Reference Jiménez and Lloret2007) and Lloret & Jiménez (Reference Lloret and Jiménez2009) suggest that vowel harmony results from languages attempting to minimize resetting of articulators; for Henriksen (Reference Henriksen2017), however, vowel harmony is due to phonological harmony, not to coarticulation, as first posited for EAS by Alarcos Llorach (Reference Alarcos Llorach1958). Likewise, although most authors believe that vowel harmony cannot travel past stressed vowels, Jiménez & Lloret (Reference Jiménez and Lloret2007) believe this can happen. The reasons given above to explain the different results in the study of vowels also apply to vowel harmony, demonstrating that there is no definite description of how vowel harmony works in Eastern Andalusian Spanish.

Further explanations of the role of stress in EAS vowel harmony can be found in Zubizarreta (Reference Zubizarreta1979), Jiménez & Lloret (Reference Jiménez and Lloret2007) and in Henriksen (Reference Henriksen2017). A more thorough summary of past studies on EAS vowel harmony can be found in Herrero de Haro (Reference Herrero de Haro2017b).

Some authors (e.g. Rodríguez-Castellano & Palacio Reference Rodríguez-Castellano and Palacio1948a, Alonso et al. Reference Alonso, Vicente and de Zamora1950, Alarcos Llorach Reference Alarcos Llorach1958) claim that EAS vowels are longer when they precede a deleted consonant. However, for Salvador (Reference Salvador1977), lengthening is not a regular feature of these vowels. On the other hand, Martínez Melgar (Reference Martínez Melgar1994) posits that all vowels are shorter when they precede an underlying /s/, although for Sanders (Reference Sanders1998), only high vowels are shorter before underlying /s/ than syllable-finally. Carlson (Reference Carlson2012) found that the duration of Andalusian vowels increased by 24.2% when they precede an underlying /s/, which she believed was the distinguishing feature in words with word-medial /s/ deletion (e.g. coto [ˈkoto] ‘nature reserve’ vs. costo [ˈkɔtːo] ‘cost’). Although further investigation is required, our analysis of /e/ in the contexts /ˈeta/, /ˈesta/, and /ˈekta/ shows instead that /e/ tends to be 9.72 ms shorter when it precedes a deleted /s/ or /k/ (F(1, 270) = 32.56, p < .05, ηp 2 = .108). The effect of coda deletion in EAS on preceding vowel duration remains an open question and more investigation is needed.

EAS speakers can lengthen and intensify stressed vowels in order to intensify meanings. This lengthening is considerably longer than that found in other varieties of Spanish in similar contexts:

Diphthongs

In Spanish, diphthongs can be formed by two high vowels (/i/ and /u/, irrespectively of the order), by a high vowel (/i u/) and a mid or low vowel (/e a o/) or by a mid or low vowel and a high vowel. A combination of either high vowel and mid/low vowel or mid/low vowel and high vowel is only considered a diphthong if the high vowel is not the stressed element.

Diphthongs preceding underlying consonants in EAS are subject to two types of modifications. Firstly, the final element of the diphthong undergoes vowel lowering in a manner similar to monophthongs. Secondly, if the first element of a diphthong is stressed, this also undergoes lowering due to vowel harmony:

Triphthongs

EAS triphthongs, which all have the stress on the middle element, behave like EAS diphthongs with the same last two elements (e.g. the last two vowels of the triphthong in copiáis [koˈpj![]()

![]() ] ‘you(pl) copy’ are the same as in the diphthong in llamáis [jaˈm

] ‘you(pl) copy’ are the same as in the diphthong in llamáis [jaˈm![]()

![]() ] ‘you(pl) call’). It is worth noting that the last element of the diphthong and triphthong above is transcribed [

] ‘you(pl) call’). It is worth noting that the last element of the diphthong and triphthong above is transcribed [![]() ] as it precedes a deleted /s/; the same applies to the examples below. To our knowledge, these are the only four triphthongs of this type (with pre-nuclear glides derived from /i/ and /u/ represented by [j] and [w], respectively):

] as it precedes a deleted /s/; the same applies to the examples below. To our knowledge, these are the only four triphthongs of this type (with pre-nuclear glides derived from /i/ and /u/ represented by [j] and [w], respectively):

Prosodic features

Lexical stress

EAS stress has phonemic value, that is, it differentiates between meanings (e.g. hábito [ˈaβito] ‘habit’, habito [aˈβito] ‘I inhabit’ and habitó [aβiˈto] ‘he/she inhabited’). In EAS, stress is transferred from the final to the penultima syllable in some proper nouns in familiar forms:

Vowel harmony

As previously noted, in EAS, stress has a key role in determining which vowels lower as a result of vowel harmony. Given its prosodic nature, we briefly represent the phenomenon here. The vowel preceding a word-final underlying consonant opens and all vowels further to the left open up as far as the stressed syllable.

Intonation

The general nuclear intonation pattern of EAS is low fall for wh-questions, high rise for yes/no questions, and progressively descending for declarative sentences; this is the same for Castilian Spanish (Martínez Celdrán et al. Reference Martínez Celdrán, Planas and Sabaté2003). However, EAS can display a very narrow range of tones in statements and in questions (Figures 3 and 4), as in Murcian Spanish (Monroy & Hernández-Campoy Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015), that differs from Castilian Spanish:

Figure 3 F0 tracing of Esa igual que tu prima el día que se murió tu abuela ![]() ‘that one, like your cousin the day that your grandmother died’.

‘that one, like your cousin the day that your grandmother died’.

Figure 4 F0 tracing of ¿Sabes lo que te digo? ![]() ‘Do you know what I’m saying?’.

‘Do you know what I’m saying?’.

Rising intonation as well as vowel lengthening can be used to intensify meanings, as exemplified in the fragment in Figure 5.

Figure 5 F0 tracing of ha suspendido una ![]() ‘She has failed one’ with lengthening of /u/.

‘She has failed one’ with lengthening of /u/.

Transcriptions

The first of the two passages is a story as told by a 43-year-old female speaker from El Ejido while the second is a transcription of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ read by the first author (from the Western Almería sub-region, as the other 60 speakers analysed for this paper). The style of transcription is in general alignment with previous illustrations of varieties of Spanish, e.g. Martínez Celdrán et al. (Reference Martínez Celdrán, Planas and Sabaté2003) and Monroy & Hernández-Campoy (Reference Monroy and Hernández-Campoy2015). We have included a phonemic transcription and a phonetic one, following Coloma (Reference Coloma2018).

‘Mi hija y las matemáticas’ [My daughter and mathematics]: Broad (phonemic) transcription

‘Mi hija y las matemáticas’ [My daughter and mathematics]: Semi-narrow (phonetic) transcription

‘Mi hija y las matemáticas’ [My daughter and mathematics]: Orthographic version

Sí, cuando se lleva, mira, terminó... hizo una multiplicación, y la primera tanga [sic] me la puso bien, la segunda me puso... Empezó por ponerme un número debajo de otro, y no era debajo, era en el siguiente, porque era el segundo. Y luego, se llevaba una y en vez de poner (eran diez lo que le daba y se llevaba una) y en vez de poner que se llevaba una puso el diez directamente, y le digo... y digo: ¿Qué es lo que has hecho? ¡Otra vez! Pero yo creo que no voy a suspender. Hombre, yo creo que no, depende también de la maestra, ahora. Pero, Alfredo, lleva cuatro veinticinco, cuatro setenta y cinco, un tres..., que son en pruebas...

‘Mi hija y las matemáticas’ [My daughter and mathematics]: English translation

Yes, when she carries, look, she finished… she did a multiplication, and she did the first one correctly, with the second one she wrote down… She started by putting one number underneath another, and it didn’t go under, it had to go next to it, because it was the second one. And then, she had to carry one and instead of writing (it was ten what she got and she had to carry one) and instead of writing down that she had to carry one, she wrote ten straightaway, and I said… and I said: What have you done? Again! But I don’t think I’m going to fail. Man, I don’t think so, it’s up to the teacher too, now. But, Alfredo, she got four twenty-five, four seventy-five, a three… which are in tests…

‘El sol y el viento’ [The North Wind and the Sun]: Broad (phonemic) transcription

‘El sol y el viento’ [The North Wind and the Sun]: Semi-narrow (phonetic) transcription

‘El viento norte y el sol’ [The North Wind and the Sun]: Orthographic version

El viento norte y el sol porfiaban sobre cuál de ellos era el más fuerte, cuando acertó a pasar un viajero envuelto en ancha capa. Convinieron en que quien antes lograra obligar al viajero a quitarse la capa sería considerado más poderoso. El viento norte sopló con gran furia, pero cuanto más soplaba, más se arrebujaba en su capa el viajero; por fin el viento norte abandonó la empresa. Entonces brilló el sol con ardor, e inmediatamente se despojó de su capa el viajero, por lo que el viento norte hubo de reconocer la superioridad del sol.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor of JIPA Amalia Arvaniti and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The collection of data samples analyzed in this paper was funded by the Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts of the University of Wollongong (Australia) and by a Hispanex grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. We would like to thank staff and students at the following schools for helping us gather the necessary materials for this paper: I.E.S. Fuente Nueva (El Ejido); I.E.S. Santo Domingo (El Ejido); C.E.I.P. Laimún (El Ejido); I.E.S. Mar Azul (Balerma); I.E.S. Virgen del Mar (Adra); and I.E.S. Abdera (Adra).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100320000146.