Dàgáárè /dàgááɹɪ̀/ (ISO 639-3) is a Mabia language (Bodomo Reference Bodomo1997) of Niger-Congo family. It is spoken by about 1.5 million The map in Figure 1 shows the areas, in northwestern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso, where Dàgáárè is spoken predominantly. There are four broad dialects of Dàgáárè. These include Northern Dàgáárè [dàgàɹà], spoken in Lawra /lóɹáː/, Nandom /nàndɔ̀ː/ and Burkina Faso; Southern Dàgáárè /wáːlɪ́/, spoken around Kaleo /kàlèó/ and in Wa /wá/; Western Dàgáárè /bɪ̀ɹɪ̀fɔ̀/ spoken in Lassie /lààsɪ̀ɛ́/, Tuna /tʊ́ːnà/ and along the western side of the Black Volta river in Burkina Faso. The other dialect is Central Dàgáárè. These broad dialects are further divided into sub-dialects, as there are internal variations in these dialect groups (Bodomo Reference Bodomo2000). This paper’s primary focus is on Central Dàgáárè, which comprises the varieties spoken in and around Jirapa /ʤɪ̀ɹɛ́bǎː/, Han /hɛ̌ŋ/, Ullo /úlò/, Daffiama /dàfɪ̀ɛ́mɛ́/, Nadowli /nàdòlí/, Charikpong /tʃɛ̀ɹɪ̀kpóŋ/, Sombo /sʊ̀mbɔ́/ and Duong /dùóŋ/.

Figure 1 Areas where Dàgáárè is spoken in northwestern Ghana and in Burkina Faso.

Most of the data in this paper come from Central Dàgáárè spoken in some parts of the Nadowli-Kaleo district, with specific focus on the variety spoken in the Sombo area. The data were elicited in Ghana from five native speakers. All five speakers were male; they were born and had lived all their lives in Sombo. They were between the ages of 31 and 45 years. The first author, who is also a native speaker of Central Dàgáárè, provided supplementary data in Vancouver, Canada. The narrative in the transcription section was recorded from a 28-year-old woman of the Daffiama /dàfɪ̀ɛ̀má/ variety of Central Dàgáárè. The data presented in this work are represented orthographically and phonemically. All orthographic forms are without brackets while all phonemic representations are in slant // brackets. Note that the Dàgáárè language as presented here as well as in Bodomo (Reference Bodomo2000: 3) corresponds to a group of between three and six languages in other publications – the Dàgáárè–Waale–Birifor linguistic continuum in Bodomo (Reference Bodomo1997: 1) and Dagaaric in glottology.org on Ethnologue.

The data were recorded with a SHURE WH30XLR cardioid condenser (a headset microphone) and Rode NGT2 supercardioid condenser (a shotgun microphone) at the sampling rate of 48 kHz and bit depth of 16 bit. The microphones were attached to a zoomQ8 camera. The data presented in this work are from fieldwork funded by Insight grant by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) to Douglas Pulleyblank.

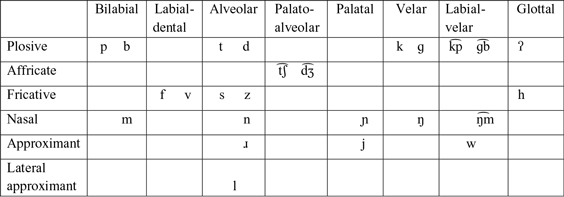

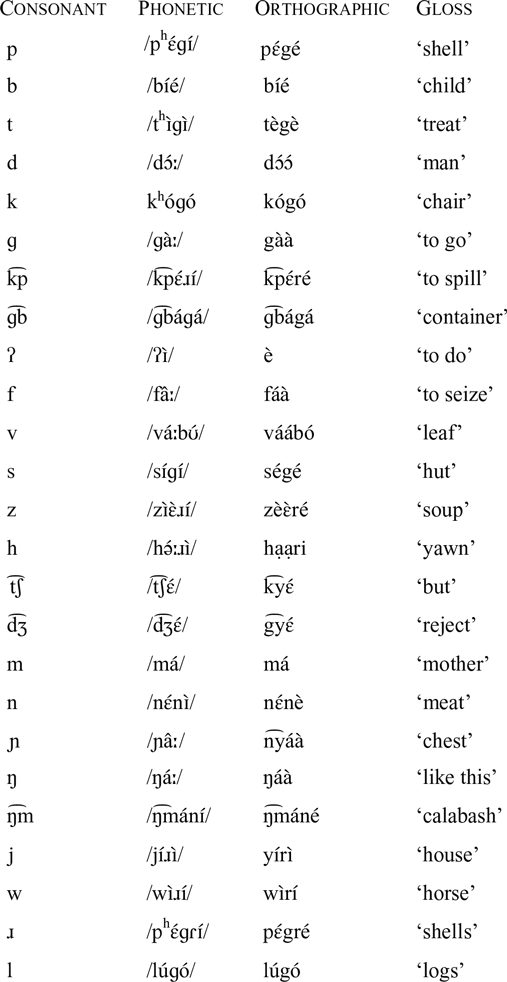

Consonants

Dàgáárè is reported to have four main varieties (Bodomo Reference Bodomo1997) that form a dialect continuum of varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Bodomo reports that Dàgáárè has 25 consonants and two glides. However, the number of consonants varies between the various dialects. In Central Dàgáárè, there are 23 consonants and two glides (semi-vowels). These include stops /p b t d k ɡ k͡p ɡ͡b ʔ/, affricates /t͡ʃ d͡ʒ/, fricatives /f v s z h/, nasals /m n ŋ ŋ͡m ɲ/, approximants /j w/, a lateral approximant /l/ and the alveolar approximant /ɹ/ which can only occur intervocalically, word-medially and root-finally. In Southern Dàgáárè (![]() ), there are 22 consonants and two glides (Abdul-Aziz Reference Abdul-Aziz2015). The voiced alveolar fricative /z/ that is present in the central, northern and western dialects is not attested in the southern dialect. Northern Dàgáárè (

), there are 22 consonants and two glides (Abdul-Aziz Reference Abdul-Aziz2015). The voiced alveolar fricative /z/ that is present in the central, northern and western dialects is not attested in the southern dialect. Northern Dàgáárè (![]() ) and Western Dàgáárè (

) and Western Dàgáárè (![]() ) are each reported to have 25 consonants and two glides (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013). The following sounds: voiceless bilabial implosive /ɓ/ and voiceless glottalized lateral /ʔl/ are attested in the northern dialect and in the western dialect. Voiceless glottalized palatal /ʔj/ and the voiceless glottalized labial-velar glide /ʔw/ are found only in the western dialect, while the voiceless velar fricative /x/ is attested only in the northern dialect. The table shows the consonants for Central Dàgáárè.

) are each reported to have 25 consonants and two glides (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013). The following sounds: voiceless bilabial implosive /ɓ/ and voiceless glottalized lateral /ʔl/ are attested in the northern dialect and in the western dialect. Voiceless glottalized palatal /ʔj/ and the voiceless glottalized labial-velar glide /ʔw/ are found only in the western dialect, while the voiceless velar fricative /x/ is attested only in the northern dialect. The table shows the consonants for Central Dàgáárè.

Aspiration

In this paper we observe that when the voiceless stops /p t k/ occur in word-initial position, there appears to be some degree of aspiration. In phonetic transcription, aspiration is indicated by a superscript h, [ʰ]. Consequently, all initial voiceless stops in this work are transcribed as /pʰ tʰ kʰ/.

Restricted distribution of consonants

In addition to the consonants listed above, Central Dàgáárè has some consonants which are restricted in their distribution, such as voiced alveolar approximant /ɹ/ and its allophonic variant the alveolar tap /ɾ/. For example, /ɹ/ only occurs intervocalically, as in /d̀-ɹé/ ‘eating’, and root-finally, as in /sʊ̀ʊ̀ɹ-ɪ̀/ ‘ask’, and in word-medial position it is occasionally realized as an alveolar tap /ɾ/ after a /ɡ/, as in /pʰɛ́ɡɾɪ́/ ‘shells’. Another sound with restricted distribution is an allophonic variant of voiced velar plosive /ɡ/. Bodomo (Reference Bodomo1997) describes the allophonic variant of /ɡ/ as a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/, as in /pɔ́ɣɔ́/ ‘woman’ and /wɛ́ɣɛ̀/ ‘log’. However, a recent acoustic, palatographic and ultrasound study (Akinbo et al. Reference Akinbo, Angsongna, Ozburn, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2020) suggests that this velar fricative is a velar with strong tap-like features, which is a previously unattested sound in human language. The findings of Akinbo et al. on the velar are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of acoustic results of Dàgáárè /ɡ/ experiment (Akinbo et al. Reference Akinbo, Angsongna, Ozburn, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2020).

In summary, although the Central Dàgáárè /ɡ/ has a longer duration than an alveolar tap, its production is most consistent with the behaviour of a tap, in terms of waveform, spectrogram, ultrasound, and palatography. In particular, it is not consistent in a number of ways with a stop or a resonant; rather it is a velar with tap-like features. Consequently, according to the report on the 1989 Kiel Convention (Roach Reference Roach1989: 70), ‘where no independent symbol for a tap is provided, the breve diacritic [˘] should be used’. Therefore, the velar tap would be represented as /ɡ˘/.

Note also that Dàgáárè has CV syllables as well as CVC syllables with either a nasal or the approximant /ɹ/ and /l/.

Vowels

The vowel inventory of Dàgáárè contains ten contrastive oral vowels.

The vowels are acoustically represented in Figure 2. The vowels were plotted using phonR (McCloy Reference McCloy2012) in R (R Core Team 2018).

Figure 2 Means for first and second formants (F1, F2) of ten vowels.

While previous studies (e.g. Bodomo Reference Bodomo1997) report that Dàgáárè has nine contrastive vowels, a recent acoustic study (Ozburn et al. Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018) suggests that Central Dàgáárè has a tenth vowel. The tenth vowel is reported to be /ə/, which is an [ATR] (advanced tongue root) counterpart of the [RTR] (retracted tongue root) vowel /a/. In this study, formants of low vowel were measured in verbal particles surrounded by different combinations of [ATR] and [RTR] vowels. The results show that the low vowel is significantly higher and fronted when followed by an [ATR] vowel compared to when followed by an [RTR] vowel, suggesting that /a/ has significantly different variants depending on whether it occurs in an [ATR] or an [RTR] context. This supports the claim in Saanchi (Reference Saanchi1997) that Central Dàgáárè indeed has ten vowels. In this paper, brackets around [ATR] and [RTR] indicate that they are phonetic features. The bare ATR without brackets is simply an abbreviated term used to refer to vowel harmony that is based on tongue root advancement and retraction.

Using Kernel density estimation, the contour plot in Figure 3 shows the distribution of the two low vowels within the vowel space based on the acoustic study by Ozburn et al. (Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018).

Figure 3 Normalised F1-F2 of /a/ by following context (Ozburn et al. Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018).

The results of the research in Lloy et al. (Reference Lloy, Akinbo, Angsonga and Pulleyblank2019) also suggest that the tenth vowel is (partially) contrastive. The list in (1) is based on the minimal pairs identified by Saanchi (Reference Saanchi1997) in (1).

(1) Minimal pairs of [ATR] and [RTR] low vowels

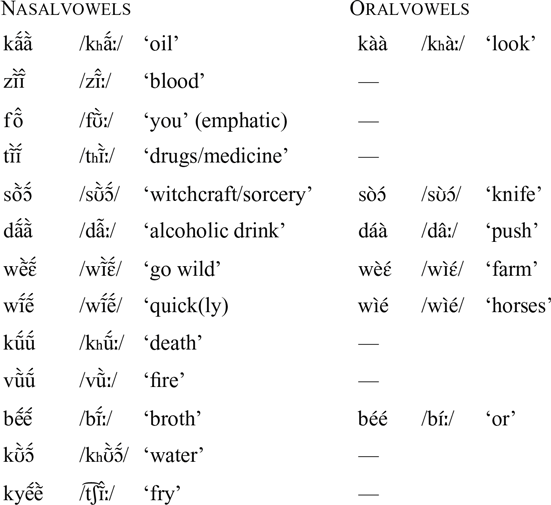

Vowel length, nasalization and co-occurrence

Vowels in Dàgáárè may contrast in length. Each vowel has a long counterpart and the differences in length of the vowels can bring about differences in meaning. However, the distinction between the short and long vowels may not necessarily be phonemic. Some examples are shown in (2).

(2) Words with short and long vowels

As reported by Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1966), Dàgáárè vowels can be phonetically nasalized when they are contiguous with nasal consonants, as seen in (3).

(3) Nasalized vowels

In addition, all vowels in Dàgáárè can show nasality even when not adjacent to a nasal consonant. In such cases, they can be referred to as nasal vowels. However, unlike in Northern and Western Dàgáárè, in Central Dàgáárè, not all nasal vowels are phonemic. Consider the examples of nasal and oral vowels in (4).

(4) Nasal vowels and oral vowels

Nasal vowels in Central Dàgáárè occur only in CVV sequences either as a long monophthong or diphthong, just like nasal vowels in the Southern Dàgáárè (![]() ). There are, however, some restrictions on the distribution of the front mid vowel /e/: it cannot occur as a long nasal vowel but can occur as part of a nasal diphthong. In the northern and the western dialects (

). There are, however, some restrictions on the distribution of the front mid vowel /e/: it cannot occur as a long nasal vowel but can occur as part of a nasal diphthong. In the northern and the western dialects (![]() and

and ![]() ), there are long CVV nasal vowels as well as short nasal vowels which occur in CV forms (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013).

), there are long CVV nasal vowels as well as short nasal vowels which occur in CV forms (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013).

In terms of sequences, vowels in Dàgáárè occur in a particular pattern. They either occur as long monophthongs or diphthongs. However, not every vowel sequence is allowed in the language. For instance, while opening diphthongs such as /ie uo/ are permitted, there is a prohibition on closing /aɪ ɔɪ/ and centering /ɪə ʊə/ diphthongs. Bodomo (Reference Bodomo1997) identifies the following phonemic vowel sequences which are the same vowel sequences in Central Dàgáárè.

(5) Vowel sequences in Dàgáárè

In addition to the sequences identified by Bodomo, the following sequences are equally possible and productive in Dàgáárè:

Vowel harmony

Dàgáárè has assimilatory processes which involve the obligatory agreement of adjacent vowels in the values of [ATR] and round features. These processes are known as vowel harmony (Archangeli & Pulleyblank Reference Archangeli, Pulleyblank and Paul2007, Rose & Walker Reference Rose, Walker, Goldsmith, Jason and Yu2011).

The ten vowels in Dàgáárè fall into two natural classes based on [ATR] feature, as seen in (7). Only [ATR] vowels co-occur with each other. Similarly, only [RTR] vowels co-occur with each other.

(7) Natural classes of Dàgáárè vowels

Stewart (Reference Stewart1967), cited in Bodomo (Reference Bodomo1997: 20), refers to the kind of tongue root harmony in Dàgáárè as cross-height vowel harmony. In this case, the feature [ATR] is distinctive at more than one vowel height and the process of harmony operates across sequences of vowels which differ in vowel height (Stewart & van Leynseele Reference Stewart and van Leynseele1979). In (8), we first show that harmony operates across the same vowel height. In the [ATR] cases, the vowels are of the same height and in the [RTR] examples, all vowels in each word are of the same height. Each example is either comprised of all high vowels or all mid vowels. Note that there is no harmony in the orthography as both [ATR] and [RTR] vowels can co-occur in the word, as in sáárè ‘broom’ and![]() ‘meat’. Harmony is realized only in the phonemic forms.

‘meat’. Harmony is realized only in the phonemic forms.

(8) Tongue root harmony across the same vowel height

The examples in (9) show that ATR harmony can operate across vowels with different heights.

(9) Tongue root harmony across different vowel heights

The vowels in /pʰíé/ ‘ten’ and /tʰùò/ ‘carry’ are combinations of high vowels /i u/ and mid vowels /e o/; they are also [ATR]. Similarly, each of the words /tʰɪ̀ɛ́/ ‘tree’ and /pʰʊ́ɔ́/ ‘stomach’ contains both high and mid [RTR] vowels.

Status of /a/ in ATR harmony

The status of /a/ in Dàgáárè ATR harmony is a topic of interesting debates. Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1966) argues that /a/ occurs with vowels showing open harmony and excludes vowels that exhibit close harmony. Open harmony involves low vowels which are made with an open mouth while close harmony involves high vowels which are made with the mouth closed. Hall (Reference Hall and Dakubu1973), on the other hand, suggests that /a/ occurs with [ATR] vowels to the exclusion of [RTR] vowels. Bodomo (Reference Bodomo1997) argues that /a/ occurs with [ATR] and [RTR] vowels.

However, as noted above, Ozburn et al. (Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018) suggest that /a/ is not neutral to ATR harmony in Central Dàgáárè. They show that /a/ is significantly higher and fronted when the following vowel is [ATR], compared to when the following vowel is [RTR], thereby suggesting that /a/ has an [ATR] counterpart. The carrier sentences from Ozburn et al. (Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018) illustrating /a/ in [ATR] and [RTR] environments are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Carrier phrases with /a/ between [ATR]/[RTR] vowels (Ozburn et al. Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018: 1).

In ![]() and in

and in ![]() , /a/ is reported to be neutral and co-occurs with both [ATR] and [RTR] vowels (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013). However, similar to what is reported in Saanchi (Reference Saanchi1997), Ozburn et al. (Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018) and Lloy et al. (Reference Lloy, Akinbo, Angsonga and Pulleyblank2019) about /a/ in Central Dàgáárè, Southern Dàgáárè (

, /a/ is reported to be neutral and co-occurs with both [ATR] and [RTR] vowels (Dundaa Reference Dundaa2013, Kuubezelle Reference Kuubezelle2013). However, similar to what is reported in Saanchi (Reference Saanchi1997), Ozburn et al. (Reference Ozburn, Akinbo, Angsongna, Schellenberg and Pulleyblank2018) and Lloy et al. (Reference Lloy, Akinbo, Angsonga and Pulleyblank2019) about /a/ in Central Dàgáárè, Southern Dàgáárè (![]() ) is said to have ten oral vowels in which the low vowel /a/ has an [ATR] counterpart /ạ/ (Abdul-Aziz Reference Abdul-Aziz2015).

) is said to have ten oral vowels in which the low vowel /a/ has an [ATR] counterpart /ạ/ (Abdul-Aziz Reference Abdul-Aziz2015).

Tone

Dàgáárè has two contrastive tones: H(igh), as in tú ‘to dig’, and L(ow), as in tù ‘to follow’ (Anttila & Bodomo Reference Anttila and Bodomo1996, Reference Bodomo2000; Bodomo Reference Bodomo1997). H tone is marked with the acute accent (́) and L tone is marked with the grave accent (̀). In some words, different tones can co-occur. Examples of the tones are shown in (10)–(12).

Downdrift and downstep

Dàgáárè has downdrift, which is the cumulative lowering of pitch in the course of an utterance due to interaction of tones (Akinlabi & Liberman Reference Akinlabi and Liberman1995, Connell Reference Connell2001). Downdrift is illustrated with a pitch track of the phrase in (13). As shown in Figure 4, the pitch of H with a preceding L is lowered.

(13) Downdrift

‘The people were eating the yam.’

Figure 4 Pitch track [L H L L L H H L L H].

When two adjacent syllables bear H tone, the pitch of the second syllable is lowered. For instance, the phrase /jí! Fáá/ ‘bad house’ contains a sequence of H! HH, the pitch of second H is lower than the pitch of the initial high. This lowering of pitch is referred to as downstep (Hyman Reference Hyman1985, Selkirk & Tateishi Reference Selkirk, Tateishi, Carol and Roberta1991). The lowering is usually represented with an exclamation mark (!) to signal an unassociated floating L tone. The following examples from Anttila & Bodomo (Reference Anttila and Bodomo1996: 14–15) illustrate this process. The lowering of the second phrase in (14a) can be visualized in the pitch track in Figure 5.

(14) Downstep

Figure 5 Pitch track [H!H!H!H].

Transcription of recorded passage

The text provided is a story entitled ‘The shea butter baby’ told by a female native speaker of the Daffiama [dàfɪ̀ɛ̀má] variety of Central Dàgáárè. Note that there is occasional intervocalic deletion of some segments like /ɡ/ and /ɹ/ in some words by this speaker especially in![]()

![]() ‘woman’;

‘woman’;![]() ‘rise’

‘rise’

PHONETIC TRANSCRIPTION

The slashes in this text indicate boundaries between sentences.

Translation

The shea butter baby

Listen to my story!

There lived a certain woman who married her husband. She was not able to bring forth children. So, the husband went for a second wife. The second wife could bear children, but the first wife still could not. Though the first wife could not bear children, she considered and treated the child of the second wife as her own. The second wife was however not happy about it and treated the first wife with discontent. So, one day, the first wife cried to her hometown (father’s house).

There was a certain old woman in the father’s house who liked the woman so much. Upon getting to her father’s home, the old woman gave her shea nuts and asked her to extract shea butter for her. She extracted the shea butter for her (the old woman). After that, the old woman asked her when she would go home. She said she would go home in three days. The old woman then went and kept the shea butter in a large pot. The day the woman said she was returning to her husband, the shea butter transformed into a baby and the old woman gave the baby to her. She (the old woman) told her that she should take this child and go with it as the only thing she had for her. She told her to never allow the child to set fire or be exposed to the sun or eat hot food, because she can only survive in cool environments.

The woman returned to her husband with the child and handled her as advised by the old woman. She raised her into a beautiful young woman. There was a certain man who had three wives, but after seeing the young woman, he wanted to marry her because she was beautiful; the mother did not agree initially. The man insisted he would marry her, the mother declined because her daughter cannot be exposed to the sun. The man said he can cater for her and ensure she is never exposed to heat. The woman agreed and gave the daughter out in marriage. The man took her home and informed the other three wives never to allow her bath hot water or eat hot food. So, the other wives did all house chores until they got fed up.

Meanwhile, their husband had gone for war and had not returned after three days. The other three wives asked her to cook and she started crying. She went in to cook and the heat from the fire made her to start melting. She sprinkled cold water on her body and continued cooking. However, the heat was too unbearable that she eventually melted completely. The other wives entered the kitchen to find that she had completely melted. There was a dog in the house, but aside the new wife, the other three wives never fed the dog. The women went to call the dog to come and eat the oil; the dog refused saying, ‘Dog will not eat oil; dog does not eat oil.’ The women chased the dog with clubs; the dog ran toward the direction the husband travelled and eventually met the man and reported the incident. The man returned on his horse to find that what the dog reported was true. Out of anger he pulled out his sword and kill everyone in the house.

Phonemic transcription with interlinear glossing

A list of abbreviations used in the glosses will be found at the end of this passage.

Abbreviations

- 2, 3

-

2nd, 3rd person

- aff

-

affirmative

- c

-

complementizer

- cnj

-

conjunction

- cop

-

copula

- d

-

determiner

- dem

-

demonstrative

- foc

-

focus

- fut

-

future

- hab

-

habitual

- ideo

-

ideophone

- imp

-

imperative

- indf

-

indefinite

- ipfv

-

imperfective

- neg

-

negation

- nmlz

-

nominalizer

- pfv

-

perfective

- pl

-

plural possessive

- pst

-

Past tense

- red

-

reduplication

- rel

-

relative

- rep

-

repetitive marker

- sg

-

singular

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the native speakers in Sombo (Nadowli-Kaleo district) who were happy to share their time and language with us during our field work in Ghana. Thanks to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their great comments and suggestions. This research is part of the project funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Insight grant (#435-2016-0369) awarded to Douglas Pulleyblank.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, (including audio files to accompany the language examples), please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100320000225.