I. INTRODUCTION

During the Liberal Age in Italy,Footnote 1 Italian economists, statisticians, and social scientists started to debate the economic effects of mass emigration: it became clear that the phenomenon was shaping the economic life of the nation in various aspects and it was thought to be necessary to better understand it, especially defining the costs and benefits of emigration and designing appropriate economic policies. From this perspective, a particular interesting example was a debate that saw the clash of two divergent views on methodology, theory, and policies. The participants were Vilfredo Pareto and Alberto Beneduce on the one side, and Francesco Coletti on the other. The debate, developed in the Giornale degli Economisti, focused on the measurement methodology of the value of men connected with the aim of quantifying the economic effects of mass emigration, and on the policies to be adopted. The reconstruction of this episode in the history of economic thought allows us to find a continuity with the problems encountered in some sections of the vast literature on the subject of brain drain, which developed starting from the 1950s.

The aim of this paper is twofold. The first aim is to backdate the roots of the brain drain research field. In the secondary literature, the first scholar to have drawn attention to this debate and to have highlighted its analytical implications was Stefano Spalletti (Reference Spalletti2005), whose purpose was to connect it with the onset of the literature on human capital. Our purpose, instead, is to place the origin of this debate within the literature on the economic effects of emigration.

Our second aim is to highlight the elements of continuity, specifically referring to the issue of the economic and social effects of emigration. In particular, we show that from the beginning of the issue, economists and statisticians struggled with: (i) the problem of properly defining a specific cost-benefit analysis regarding emigration; and (ii), as a consequence, the problem of recognizing a clear set of economic policies designed to manage the complex economic and social processes connected to emigration.

After an overview of the Italian context in which the debate among the Italian economists took place (section II), we very briefly retrace the long tradition that the idea of measuring the “cost of human production” and the “value of men” has in the history of economic thought (section III). Sections IV and V are devoted to the analyses of Pareto and Beneduce on the cost of human production related to the issue of Italian emigration, to the criticisms that Coletti raised regarding the methodological and theoretical structure of Pareto’s and Beneduce’s analysis, and to the different economic policies derived from these divergent views. Section VI is devoted to the emigration policies adopted until the fascist regime, which in Italy marked the break with the Liberal Age. In section VII, through a wide review of the vast literature on the subject of the brain drain that has developed since the 1960s, we show that the problems of defining and measuring the costs of emigration, and possibly setting up appropriate economic policies, are still at the center of the debate. Section VIII shows the elements of continuity between the early Italian debates and the literature on brain drain, and Section IX proposes some concluding remarks suggesting an explanation for the lack of conclusive results in this literature.

II. THE ITALIAN CONTEXT

Italian emigration from the post-unification period (1861) to the First World War (1915) was an impressive phenomenon caused by an intertwining of demographic and economic factors. It had a very profound and lasting impact on the country’s institutional structure and on the legislative activity of the new unitary state.Footnote 2 Emigration was not a completely new phenomenon for Italy, at least in the North of the country. Since the early decades of the nineteenth century, a system of seasonal migrations had developed between the regions of northern Italy and the regions of western and northern Europe in correspondence with the needs of agriculture and the construction of infrastructural works that required large quantities of workers.

The emigration that developed since 1861 responded to profound changes arising not only from the new institutional political structure of the just-born nation. As in other cases of “modernization” in Europe, the most intense emigration from Italy occurred during the phases of economic growth acceleration, that is to say between the end of the 1880s and the first decade of the 1900s (Sori Reference Sori1979, p. 40). According to Douglas Massey’s estimates, in western Europe, from 1850 to the 1920s, the processes of economic growth and industrialization involved forty-eight million emigrants. Of these, 41% came from Great Britain, the engine of the Industrial Revolution. This phenomenon is due to the fact that the process of economic development inevitably destroys the pre-industrial socio-economic system and indirectly triggers migration processes. “Together the processes of capital accumulation, enclosure, and market creation weaken individuals’ social and economic ties to rural communities making large scale emigration possible” (Massey Reference Massey1988, p. 392). Very important for the Italian emigration were also the strong factors that attracted workers, expressed by the international labor market of the second half of the nineteenth century: the tumultuous development of European capitalism, the opening of new overseas territories, and the growth of the North American economy.

As for the Italian economists, the majority of them were in favor of emigration. Some suggested regulating the phenomenon through appropriate legislative action by the state, without, however, preventing in principle the freedom of individual movement.Footnote 3 According to the Italian liberal economist Francesco Ferrara, if individuals are to be considered as an “accumulation of capital,” emigration would certainly result in a loss of capital for the country of departure. But this comparison, according to Ferrara, must be taken to its extreme consequences because it must be considered that departing workers are not valued in the country they leave from. “Any wealth, if it is inert, paralyzed, unable to produce, first loses its character as capital and soon after will lose the character of wealth” (Ferrara [1855] Reference Ferrara1889, p. 668). Gerolamo Boccardo, another Italian economist of that age with a more eclectic orientation, pointed out that emigration was a formidable tool to encourage the export of Italian goods to the countries of destination of the emigrants (Boccardo Reference Boccardo1875). This was a recurring theme in the analysis of economists who foreshadowed a sort of “peaceful” colonization through emigration. The most advanced exponent of this vision was Luigi Einaudi,Footnote 4 who, starting from a view of a successful case of Italian emigration to Argentina, highlighted the possibilities of expansion of Italian capitalism in Latin America (Einaudi Reference Einaudi1900).

However, this was not the only position of Italian economists toward the new phenomenon of emigration. As we will see below, it is possible to summarize their articulated attitudes focusing on their analysis of emigration’s economic effects and implications.

The discourse around these issues started to be conducted on a scientific basis through the collection, analysis, and interpretation of statistical data. It is in this period that statistics began to be defined in Italy as an autonomous sector of investigation,Footnote 5 also through the contribution of Pareto, Beneduce, and Coletti. According to the participants in these debates, the statistical survey had the task of providing the scientific basis necessary to define the public policies for the development of the state. It is in this context, therefore, that a debate in the Giornale degli Economisti on the subject of measuring the economic effects of Italian emigration developed.

The journal, which was founded in 1875, started a new series in 1890 co-directed by Alberto Zorli, Maffeo Pantaleoni, Antonio de Viti de Marco, and Ugo Mazzola. Together with Vilfredo Pareto and Enrico Barone, they constituted the core of the Italian marginalist tradition: they were pure theorists as economists and militant free trade and free market intellectuals in the political sphere, until the rise of fascism (Mosca Reference Mosca2018, pp. 29–31). They radically transformed the theoretical orientation of the journal, which, from being a supporter of protectionist positions and in favor of legislative intervention in the field of social security and labor protection, became liberal, anti-protectionist, and anti-socialist. The new direction also increasingly set the Giornale as the forum for discussion and debate of marginalist economic theory (Magnani Reference Magnani2002, ch. 5).

Pareto, from 1891 to 1897, constantly contributed to the journal, not only with path-breaking theoretical articles but also with a very polemical column dedicated to comment on the political events of the month. Starting from 1904, Beneduce, a statistician and demographer, also collaborated with the Giornale degli Economisti, and in 1910, with Pantaleoni and Giorgio Mortara, became director of the journal, starting another new series and adding the reference to statistical studies in its title.Footnote 6 Beneduce later became a leading figure in the administration of the Liberal state and in the fascist government as an expert in financial and banking matters and in the management of state-controlled companies (Bonelli Reference Bonelli1966). Coletti was an applied economist and a statistician, mainly interested in agriculture and emigration, besides being close, during the 1890s, to the Italian Socialist Party. He was engaged in several debates with the exponents of the Italian marginalist tradition on themes related to trade policy and social legislation, and even on more theoretical issues, like the Marxian theory of value (Prévost, Spalletti, and Perri Reference Prévost, Spalletti and Perri2017).

Before analyzing the Italian debate on the cost of human production in the emigration context of the Liberal Age, we focus below on the analysis of this theme in the history of economic thought.

III. THE MEASUREMENT OF THE “VALUE OF MEN” AND THE ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF EMIGRATION

The Italian debate on the cost-benefit analysis regarding emigration and on the related economic policies revolved around the approach of the so-called cost of production of men, elaborated by economists of the past, prior to this debate, in order to provide a methodological tool necessary to measure the value of the working population considered as a form of capital. This historical background to the Italian discussion is needed to clarify both the concept of “value of men” and the methodological problems related to its measurement. Two different approaches emerged in the economic literature for measuring the value of men as a form of capital. The first is based on the cost of production (net of subsistence) and the second is based on the estimate of the present value of future perceptible income of workers (net or gross of subsistence) (Kiker Reference Kiker1966; Folloni and Vittadini Reference Folloni and Vittadini2010). As we will see, Italian economists developed their reasoning referring to the first approach. In the history of economic thought, the definition of these alternative approaches was often linked to the measurement of the costs and benefits deriving from migration.

In the mercantilist approach, when a general orientation favorable to population growth was prevalent, the increase in the “production” of men was seen as bringing with it various advantages for the state in terms of an increase in the number of workers and in the aggregate production, an increase in exports and tax revenues, and, more generally, advantages in the welfare of the population and in the prestige and power of the state (see Perrotta Reference Perrotta2004, pp. 168–170; Sunna Reference Sunna, Faccarello and Kurz2016, pp. 452–454). During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe, as population was considered the main productive force, mercantilists proposed two different orders of policies to enlarge population. The first was to maximize the use of the available labor force, reducing unemployment and underemployment; the second concerned the increase of the active population through immigration, above all, of skilled labor (Spengler Reference Spengler and Hoselitz1960, pp. 28–30). During the seventeenth century specific laws designed to favor the increase of the population and immigration, and to contrast emigration, were enacted in Spain and Germany, while in France they opted for measures to support the income of large Catholic families (Glass Reference Glass1952, pp. 85–86). The orientation favorable to state intervention in the matter of populationist policies is well summarized by William Petyt, the author of Britannia Languens (1680). He underlined that population is a form of capital, as far as every production derives from it. Labor, in order to be productive and to favor the greatness of the kingdom, must be governed by the state by specific policies, instead of being under the control of private enrichment interests (in Perrotta Reference Perrotta2004, p. 168).

In the same vein, William Petty ([1676] Reference Petty1690) in the Political Arithmetick, which, significantly, in the subtitle describes the meaning of his work as “A Discourse Concerning The Extent and Value of Lands, People, Buildings: Husbandry, Manufacture, Commerce, Fishery, Artizans, Seamen, Soldiers; Publick Revenues, Interest, Taxes, …,” described and enumerated the policies necessary for the improvement of the power and wealth of England. In search of par value between land and labor, he claims that the “value” of people is measured mainly through the contribution given by workers to the production of commodities and through tax revenues. In the Political Anatomy of Ireland ([1672] Reference Petty and Hull1899, pp. 192–193), Petty analyzes the effects of emigration for the purpose of calculating the value of land rent, consumption, and, more generally, the loss of value associated with the mobility of the population.

Richard Cantillon, in the Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général ([1755] Reference Cantillon and Thornton2010), discusses the question of measuring the cost of men’s production, when it is commensurate with the value of the land. Contrary to Petty, Cantillon theoretically demonstrates that landowners must provide for workers’ needs by producing goods that are at least double the land needed to support them. In this way, the workers can raise enough children to keep the workforce constant over time. Cantillon also states that the amount of land needed to support the workforce varies based on the professions and, above all, the different national and social contexts (pt. I, ch. xi).Footnote 7 Cantillon is ultimately the first author to emphasize the need to measure the value of labor in monetary terms, despite the fact that it is commensurate with the productivity of the land. Cantillon also specified that emigration and, more generally, the decrease of the population are connected with the dynamics of foreign trade. If a country exports its raw materials and its subsistence goods to purchase luxury goods, this decreases the availability of the subsistence necessary for the very survival of the population. The overall effects are poverty increase, starvation, and emigration (Cantillon [1755] Reference Cantillon and Thornton2010, p. 77).

Adam Smith, in the chapters of his Wealth of Nations devoted to the theory of wages, takes up Cantillon’s reasoning by making the value of work commensurate with the wages necessary to support the worker and his family and concludes that population growth can take place only in the “progressive state” where the growing labor demand allows for an increase in wages and a “liberal” level of subsistence (Smith [1776] Reference Smith, Skinner and Campbell1976, bk. I, ch. 8). Unlike the mercantilists, he did not believe that labor migration was as decisive a factor in the development of nations.

On the specific issue of emigration, Thomas Robert Malthus discussed in his Definitions in Political Economy the solution proposed by John McCulloch to relieve the misery in Ireland by promoting emigration that would result in an adjustment in the proportion between capital and labor, given the increase of Irish population: “But if … in all economical discussions, man is to be considered as capital, precisely like the machine which he uses or the food which he consumes, the emigration of a portion of the population will be to deprive the country of a portion of its capital, which has always been considered as most pernicious” (Malthus Reference Malthus1827, p. 91). The issue of emigration and the question of the “correct” cost-benefit analysis related to it, once again, was crucial to understand how to interpret this phenomenon, which, as we have seen, was viewed alternatively as an opportunity or an obstacle in the progress of societies. From another level of analysis, more generally, all classical authors, through the value theory of labor, were looking for a measurement of value corresponding to human labor.

As it is well known, marginalist and neoclassical authors abandoned the labor theory of value, but in some cases, as in the cases illustrated below, they did not give up the search for a monetary unit of the measurement of human value. Alfred Marshall, for example, in the Principles, discussing the extensions of the theory of supply and demand for the determination of the value of labor, cites the theme of the determination of the cost of production of men and specifically mentions the example of the value of immigration in terms of wealth for receiving countries. In this regard, Marshall discusses the most appropriate calculation methodology for estimating human value;Footnote 8 i.e., whether it is more appropriate to “discount the probable value of all the future services that he would render; add them together, and deduct from them the sum of the discounted values of all the wealth and direct services of other persons that he would consume,” or, alternatively, to “estimate his value at the money cost of production which his native country had incurred for him; which would in like manner be found by adding together the accumulated values of all the several elements of his past consumption and deducting from them the sum of the accumulated values of all the several elements of his past production” (Marshall [1890] Reference Marshall2013, p. 469; emphasis in the original). In conclusion, using both estimation methodologies, Marshall believes that the average value of an immigrant can be estimated at around 200 pounds (Marshall [1890] Reference Marshall2013, p. 470). Marshall’s systematization of the alternative methodologies was very influential in the following Italian debate and often quoted as a starting point of reference to the question of measuring the cost of emigration, like in Coletti (Reference Coletti1905a).

To sum up, since the mercantilist period, economic reasoning has been concerned with measuring the “cost of production of men,” with the aim of identifying a measure of value associated with the increase or decrease in the number of men on a national basis. From the point of view of the “cost of production” approach, the general thesis behind this enquiry was related to the perception that the value of an individual is linked to his cost of production, that is to say, to what has been spent to raise and educate that individual from the moment of birth up to the considered age. The Italian debate between economists and statisticians that we analyze concerned not only the methodology of estimating the cost of emigration but also the use of these estimates for the purposes of any applicable economic policies.

IV. PARETO’S AND BENEDUCE’S VIEWS

The constant increase in Italian emigration at the end of the nineteenth century brought to the fore the issue of its economic and social effects. In the Cours d’économie politique, Pareto estimated that from 1887 to 1893 emigration had “stolen” from Italy 400 to 450 million lire a year (Pareto [1896–97], Reference Pareto1953, vol. I, §254, p. 181). Pareto explicitly defined the working-age population (from twenty to fifty years of age) as “personal capital” and dedicated the first chapter of his Cours to the analysis of the economic determinants of the demographic dynamic. Regarding emigration, Pareto maintained: “In ancient times, emigration was, it seems, an effective remedy for an excess of population. In modern times its effectiveness is much lower because the cost of human production is such that emigration takes out of the country, with men, very considerable sums of capital” (Pareto [1896–97] Reference Pareto1953, vol. I, §249, p. 174).Footnote 9

Pareto’s reasoning is connected to two aspects. First, in “ancient times” emigration was a way to relieve demographic pressure and it did not represent a dead-weight loss for the country of departure, as the cost of human production was very low. Second, at the end of the nineteenth century, given the increase in the cost of production of men, the growth of emigration constituted an economic problem for the country of departure. This second aspect of the reasoning was motivated by the estimates on the cost of production of men that Pareto drew from the studies of Ernst Engel (Reference Engel1866, Reference Engel1876), which he cited both in the Cours and in a previous analysis on the calculation of the cost of infant mortality (Pareto Reference Pareto1893). With his tight and rational style, Pareto, using this methodology for calculating the cost of infant mortality, argued that the data do not confirm the thesis according to which a high infant mortality rate would result in an aggregate loss of wealth compared with a situation in which the rate is lower. Comparing Bavaria and Switzerland, Pareto argued that, given that the cost of raising newborns is much lower than that of a boy or an adult, in the case of Switzerland when a boy dies, the loss in relation to the cost of producing the man is higher than in Bavaria, which instead has higher infant mortality rates. According to Pareto, the methodology used to calculate the cost of infant mortality can also be used to calculate the cost of emigration (Pareto [1896–97] Reference Pareto1953, vol. I, §255, p. 182).

Engel’s studies were very influential in this period and were cited, directly and indirectly, by all the authors who dealt with the subject of measuring the cost of production of men. In summary, Engel argued that the value of an individual of a certain age must be considered equivalent to his cost of production, that is to say, to the amount spent to raise and educate that individual from birth until the considered age. According to Engel’s estimates, referring to Prussia, this cost is 100 marks at birth and, following an arithmetic progression, the cost increases by ten marks per year until the twenty-sixth year of age (Engel Reference Engel1866, Reference Engel1876). The Pareto estimates, referring to the Italian case, essentially used the same approach and aimed to measure the value of men with the purpose of being “able to form an idea of the importance of the capital that emigration takes away from a country” (Pareto [1896–97] Reference Pareto1953, vol. I, §255, p. 182).

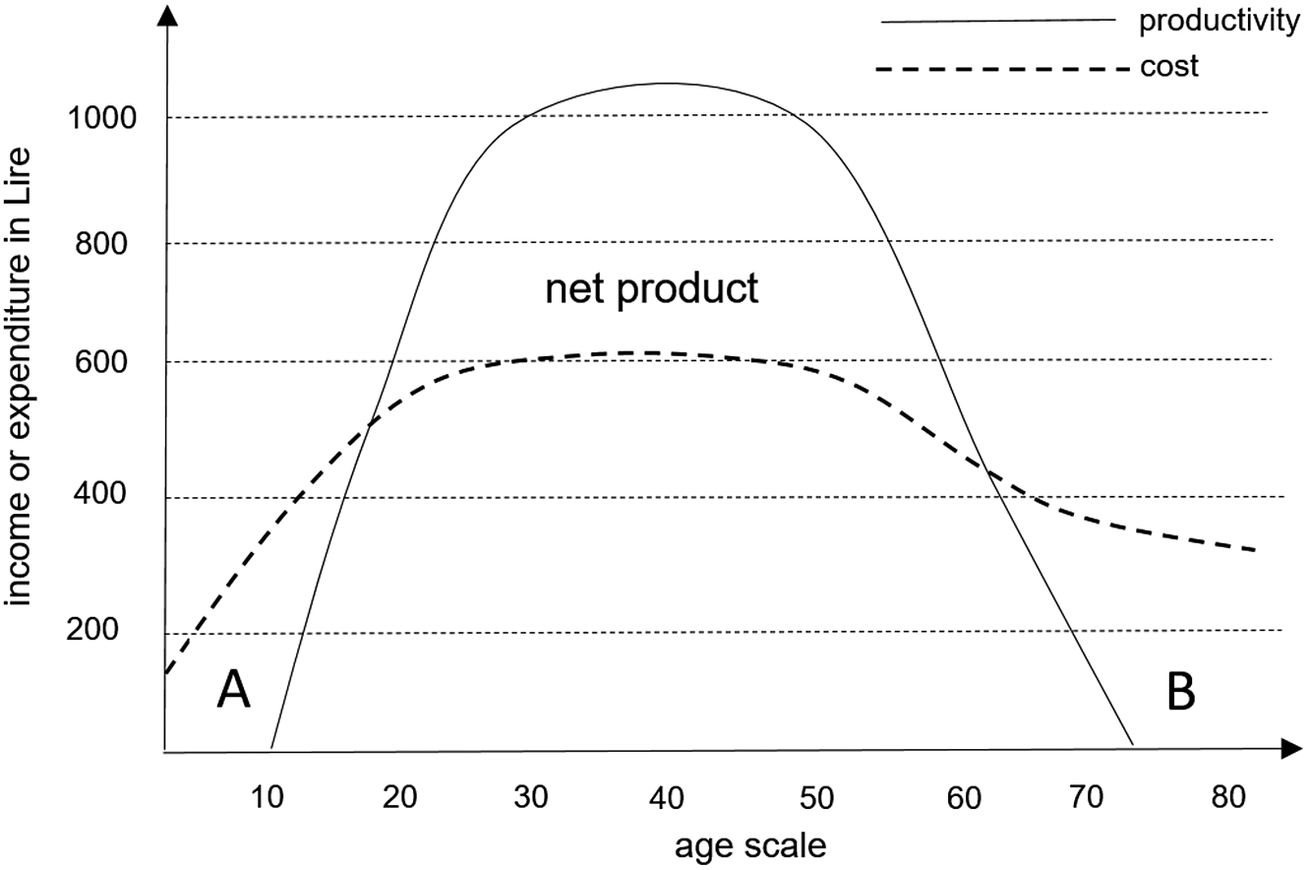

The Italian statistician and demographer Rodolfo Benini, in the commemoration published after Pareto’s death in the Giornale degli Economisti in 1924, represented in a graph (Figure 1) the analysis of the cost of production of men that summarizes the reasoning of Engel and Pareto (Benini Reference Benini1924, p. 95).

Figure 1. Theoretical Representation of Cost and Productivity of Men

The age scale of the workers is represented on the x-axis, while an estimate of the incomes and expenses incurred over the life of the workers is indicated on the y-axis. The graph shows the trend of the cost and productivity curves of workers, highlighting that, in areas A and B, the cost is greater than productivity. The area identified as net product corresponds to the maximum of labor productivity, which is expressed from twenty to sixty years. Pareto’s concern about mass emigration was essentially related to the departure of workers during their period of maximum productivity while the phase in which costs were higher than productivity fell entirely to the country of departure. This approach was essentially centered on the aggregate estimate of the alleged loss of “personal capital” generated by emigration. From this point of view, as we will specify later, even if emigrants were not educated or possessed high professional skills, it was perceived by Pareto that Italy was hindering its economic development possibilities due to the “draining” of population through emigration.

In 1904 Beneduce argued that it was necessary to “re-establish” the discourse on the cost of emigration initiated by Pareto through a better articulation of the emigration problem and, above all, starting to think not only about the costs but also about the benefits deriving from it (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904). Using the estimates of the statistician Enrico Raseri (Reference Raseri1892) and of the Direzione Generale di Statistica, the national office of public statistics of the time, Beneduce calculated the cost of emigration for 1903 by diversifying by type of worker (peasants and workers) and concluded that the average annual value of emigration in that year was 380 million lire (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 513). To this “personal capital” he added the mobile capital that each emigrant brings with him, estimated at around 200 lire (i.e., $10 per capita for the emigration of workers to the United States who do not already have an economic or familial relationship in the country of arrival, estimated by Beneduce to be around 73% of migrants; Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 513). This sum takes into account both the cost of the ship ticket and the availability of personal capital that migrants must prove they have on arrival in order not to be declared “paupers” and be rejected at the border. Given the numbers of emigration from Italy in 1903, it is therefore necessary to add 34 million lire to calculate the “annual loss of mobile capital” (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 513). By subtracting the number of returns to their homeland from the total sum, Beneduce concluded that the total cost of emigration was 287 million lire per year (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 514).

Once the cost of emigration has been established, the novelty introduced by Beneduce concerns an estimate of the benefits of emigration. In particular, the author refers to three categories of benefits. The first is the remittances of emigrants. For 1903, using the report by the politician Eduardo Pantano of the Commissione parlamentare sul fondo dell’emigrazione (Parliamentary commission on the emigration fund), they are estimated at about 200 million lire (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 515). The second positive factor concerns the increase in maritime trade favored by the flow of “man-goods” and the export of goods to the countries of destination of the emigrants but also by the development of the Italian merchant navy, which transports immigrants to the countries of destination (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 516). The third factor, according to Beneduce, is that there would also be indirect benefits deriving from emigration linked to the easing of demographic pressure on resources (especially felt in the South of Italy) and the consequent increase in real wages for agricultural workers, which would create an incentive for the mechanization of work in the countryside (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, p. 517).Footnote 10 In conclusion, according to Beneduce, “emigration is, in the current conditions of Italy, economically good” (Beneduce Reference Beneduce1904, pp. 517–518).

We can say that Pareto and Beneduce, with their analytical and statistical approaches, attempted to analyze the effects of emigration in a perspective that can be defined as macroeconomic. The question that their investigation sought to resolve was whether emigration could constitute an economic problem for Italy or whether, also considering the benefits, it could be economically advantageous for the country.

V. COLETTI’S CRITICISMS AND PARETO’S REPLY

The expansion of the factors considered by Pareto and Beneduce to measure the economic effects of emigration was radically questioned by Francesco Coletti, who, again from the pages of the Giornale degli Economisti, highlighted all the shortcomings of the methodology for calculating the value of men, which, as we have seen, was the basis of the cost-benefit analysis of emigration proposed by Beneduce. Coletti, in 1905, wrote a long polemical article criticizing the methodology for measuring the cost of human production applied to emigration. His analysis essentially focused on two types of arguments: the first was statistical and the second was economic.Footnote 11

From a statistical point of view, for Coletti, the calculations of the cost of human production (which in most of the literature cited refers to the working class) were vitiated by the incompleteness of the data. The hypothesis of Engel’s arithmetic progression, which Pareto and Beneduce endorsed, was to be rejected because it did not consider various factors that were activated in the presence of population growth. For example, as the family unit increases, according to Coletti, the commitment to work by the whole family unit (which includes women and children) also increases. In substance, it increases the total income produced, and this factor should be computed in the calculation of the cost of production of men (Coletti Reference Coletti1905a, pp. 262–263). Furthermore, anticipating a vast amount of literature on the subject of the production and reproduction of labor, Coletti argued that the statistics on the cost of production of men did not consider the cost of the mother’s care activities. When these activities are carried out outside the family unit, they have a cost and therefore represent a value that should be included in the general calculation (Coletti Reference Coletti1905a, p. 264).

Coletti’s criticism from an economic point of view essentially focused on the refusal to detect the economic value of emigration starting from the cost of production of the emigrants. The heart of the problem, for him, was in the fact that, in the literature that Coletti criticized, migrants were considered to be on a par with other forms of “movable” capital, but the worker who emigrates “does not sell himself,” he sells his workforce (Coletti Reference Coletti1905a, p. 268). In Coletti’s words, “the productivity of labor … cannot be assumed, a priori, by reason of the cost of producing personal capital. It depends on the quantity and intensity with which human labor is employed” in the individual production combinations and when it is associated with other production factors, such as land, machinery, and so on (Coletti Reference Coletti1905a, pp. 272–273). Individuals are also profoundly different from each other in terms of labor productivity: “considering a priori … that all emigrants always have a value … and that the economy of the country of origin suffers a subtraction of wealth corresponding to the sum of these values is a logical absurdity and an economic absurdity” (Coletti Reference Coletti1905a, p. 284).

In conclusion, according to Coletti, the greatest risk that can be incurred following the approach of calculating the cost of emigration in terms of dead-weight loss for the country of departure (and here the controversial target is directed specifically at Pareto) is to hinder emigration on the basis of improper and incorrect calculations.

Pareto’s reply was published a few months later, again in the Giornale degli Economisti. He accepted, albeit controversially, Coletti’s remarks, which he considered overall to be appropriate, but, at the same time, argued that “a problem of economics or sociology can never be solved with the rigor and certainty that the solution of a mathematical problem gives; you can only get approximate and more or less probable solutions” (Pareto Reference Pareto1905, p. 325). With regard to the implications of economic policy that derived from partial and/or approximate theoretical or empirical approaches, Pareto argued that “it would be foolish for the statesman to condemn emigration only because there is an expense to be written out; but he would also be unwise if he voluntarily closed his eyes and ears, so as not to see and not to hear how much that expense is” (Pareto Reference Pareto1905, p. 327). Pareto’s answer ultimately remains quite vague since he did not enter into the merits of Coletti’s precise criticisms and merely observed that emigration can represent a cost for a country and that it is important to have national awareness about the amount of this cost. Coletti replied to Pareto in a short note in 1905, again from the pages of the Giornale degli Economisti, reiterating all his arguments against the methodology of calculation and the use of the same for the direction of economic policy on emigration (Coletti Reference Coletti1905b). The debate ended without further replies.Footnote 12

Notice that Coletti adopted a point of view that was radically different from Pareto’s. He investigated the deeper causes of the phenomenon of emigration by developing a subjective, psychological theory, in which he argued that the individual decision to emigrate was made when the perception of the costs of emigration were lower than the expected benefits, or, alternatively, that the inconvenience of migrating was lower than the inconvenience of staying in the country of origin (Coletti Reference Coletti1899; Reference Coletti1911, p. 159). In later works he also studied the collection of statistical data on Italian emigration from a methodological point of view (Coletti Reference Coletti1911, ch. 1) and concentrated on the analysis of the economic and social effects of emigration. Coletti managed to grasp that emigration could not be analyzed only as one of the items in the national accounts as it produced transformative and permanent effects on social behavior. Emigration, in addition to bringing the benefits to the national economy also traced by Beneduce, had allowed a sudden “modernization” of the living conditions of farmers and the most backward areas of the country. It had allowed the “awakening of consciences” that could be observed in the behavior and attitude of returning emigrants characterized by “independence of character, a greater sense of their dignity and rights, little or slight awe of the ancient masters.” Emigration “has banished from souls the Middle Ages that lingered serious and tenacious there” (Coletti Reference Coletti1911, pp. 251–252).

In the Trattato di Sociologia Generale, Pareto, without citing Coletti, marginally discussed the question of whether emigration is a viaticum for civilization and concluded that “these characteristics [of civilization], at least in part, do not depend on reasoning, on the logic of men, on the knowledge of a certain morality, of a certain religion, etc.” but that they depended on the innate characteristics of the subjects and, from this point of view, it was still necessary to demonstrate the validity of the linkages between emigration and civilization in more scientific terms (Pareto Reference Pareto1916, p. 274).

The debate was over, but the distance between the contenders remained unchanged.

VI. THE EVOLUTION OF EMIGRATION POLICIES FROM THE LIBERAL AGE TO FASCISM

Ultimately, Italian economists during the Liberal Age were opposed to any form of limitation of emigration, which, instead, since 1888, the year of approval of the first law on this issue, had been periodically questioned by the liberal political class, who tried to mediate the various economic interests triggered from emigration. These concerned landowners, shipowners, shipping companies, and even the state, given the growing volume of emigrant remittances. Despite everything, the liberal cornerstone of freedom of migration had never been questioned during the Liberal Age.

Already in the interwar period, however, the political framework began to change and the nationalist alignment became more and more pressing in both the political and economic spheres.Footnote 13 This involved a radical change in the orientation towards emigration, which was considered one of the tools of foreign policy. In other words, Italian citizens, who worked abroad and had not renounced their citizenship, had to respond to the policies imposed by the state (Rosoli Reference Rosoli1999, pp. 59–60).

The rise of fascism did not initially change the nationalist approach aimed at maximizing the benefits deriving from international labor markets. At the same time, however, the nationalist rhetoric had to deal with the process of progressive closure to migration, especially by the United States, which, starting from 1917, with the approval of the Immigration Act, introduced a literacy test on the borders with the objective of limiting immigration from the countries of southern and eastern Europe. In 1924 the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act imposed national entry quotas on an annual basis that should not exceed 2% of each nationality present in the United States at the date of 1890. The reference date had been identified in order to “terminate the immigration of Catholics, Jews, and Orthodox Christians from southern and eastern Europe” (Leonard Reference Leonard2016, p. 141).

The demographic and migration policy of fascism, precisely in 1924, was presented by the leader of the fascist regime, Benito Mussolini, in a speech to the Senate. The policy aimed to solve the problem of Italian overpopulation through processes of internal and foreign colonization and controlled migration of the population. Another objective was to intensify bilateral agreements with the countries of greatest Italian emigration (Glass [1940] Reference Glass1967, pp. 449–450).

Starting in 1926, Mussolini’s reaction to the “closed door” policy by the United States fits into the broader picture of the transformation of the state in a fascist sense towards dictatorship. The issues of emigration were completely overcome by the pro-natalist demographic policy that was promoted, and a decisive process of limiting emigration and dismantling of the institutions created during the Liberal period to control migratory phenomena was triggered (Glass [1940] Reference Glass1967, pp. 221–224).

The research questions and surveys proposed by economists and the debate analyzed during the Liberal Age on the evaluation of the economic effects of emigration were swept away by the fascist regime.

VII. THE ENDURING CHARACTER OF THE PROBLEMS IN THE BRAIN DRAIN LITERATURE

What is relevant to us at this point of our analysis is to show that, in the vast literature that has developed especially since the 1960s on the subject of brain drain, there are some elements of continuity with the debate that took place in Italy at the turn of the century.

The expression “brain drain” was coined in the 1950s by the Royal Society of London, in reference to the outflow of scientists and technologists towards the US and Canada. However, we are still hard-pressed today to find a common definition in literature. Sometimes the definition is vague, sometimes, on the contrary, too narrow.Footnote 14 The literature on brain drain has developed impetuously since the 1950s with widespread contributions in different disciplinary approaches within the social sciences.Footnote 15 Our purpose is not to compare the Italian debate with all the literature on brain drain but to emphasize, first, the expansion and variability of traceable definitions of “brain drain” and, within that literature, to link the Liberal Age Italian debate with the line of analysis focused on cost-benefit analysis of emigration. In this specific area, the parallelism between these two seasons of investigation is particularly fruitful.

An initial look at brain drain literature shows us that the topic has been examined in all lights. Simon Commander, Mari Kangasniemi, and L. Alan Winters (Reference Commander, Kangasniemi, Winters, Baldwin and Winters2004) describe three main streams of literature based on a chronological approach: (1) an early analysis, the gist of which was that skilled migration had a negative effect on those remaining behind in the country of origin, and that migration was damaging to countries of origin; the suggestion was that skilled migration be prevented or taxed, but there does not seem to be evidence of these policies ever being put into place; (2) a later approach with models focusing on the accumulation of human capital and the motivation for brain migration, with findings stating that the drain encouraged the creation of skills, and so with a rather positive view overall; (3) a third stream of literature connecting economic geography, offering an alternative view to migration, so indirectly to brain migration, where the phenomenon of agglomeration likely leads to a negative effect only in the smallest developing countries.

Although there is a chronological progression in much of brain drain literature, it is useful for our aims to adopt a thematic approach, which favors the comparison of the analysis of the scholarly debate on Italian emigration dealt with in the previous sections. Indeed, many of the topics are recurring and continue to be discussed in the literature on brain migration still today. Starting from the late 1960s, after the initial bout of brain drain literature, focusing for the most part on the flow of human capital from Great Britain to Canada and the USA (Johnson Reference Johnson1965; Grubel and Scott Reference Grubel and Scott1966; Brinley Reference Brinley1967); much of the focus is then placed on migration from underdeveloped/developing countries to developed ones (Johnson Reference Johnson1967; Aitken Reference Aitken1968).

Regarding our first topic, one of the greatest problems identified in brain drain research is the lack of or incompleteness of data. In his work in 1970, George B. Baldwin reiterates the problematic nature of the data, affirming that they are often vague or incomplete. He specifically mentions that there are three problems in particular: geographical differences in data collection (for example, in many European countries and developing countries, data are poor), the lack of qualitative data that could help find and define the real “drain” of key individuals (not based solely on educational level), and data missing regarding returnees (immigrants are often logged by occupation and country of origin but not considered when they return to their home country, which is of great importance given that, likely, they are returning home with added value) (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1970).

The problem of missing data continues throughout the literature. In 1997, John Salt pointed out that the highly skilled migrants are often “invisible,” probably due, at least in part, to the fact that they do not “create problems” and therefore there are relatively few data regarding both the numbers and the characteristics of the same (Salt Reference Salt1997).

More recently, various scholars have confirmed the gap in data and empirical evidence to support the numerous theories of migration, especially for specific related issues such as knowledge flow and return investments (Gibson and McKenzie Reference Gibson and McKenzie2011). Others claim that due to the constraints in data, many studies are not able to adequately identify the causal effects of skilled migration and that the quantity of data is greatly inferior to the data, for example, on international trade and capital flows (Docquier and Rapoport Reference Docquier and Rapoport2012) but no less important. As we have seen in the Italian debate, mutatis mutandis, Coletti also highlighted the problem of the “quality” of data in his criticism of the methodological approach adopted to measure the aggregate cost of emigration.

The second topic that is useful for our analysis refers to one of the main reasons for the missing data, which lies in the lack of a clear definition of what is meant by a “brain” and a “drain.” Few authors specifically define what they consider a “brain migrant.” Moreover, although some examine specific brain categories in their works, such as PhD students or specific groups of professions (Das and Sharma Reference Das and Sharma1974; Simon Reference Simon1976; Lien Reference Lien1993; Liu-Farrer Reference Liu-Farrer2009), many others simply talk about skilled or highly skilled migrants (Savona Reference Savona1972; Portes Reference Portes1976; Monterroso and Grossman Reference Monterroso and Grossman1986; Appleyard Reference Appleyard1989; Carrington and Detragiache Reference Carrington and Detragiache1998; Ansah Reference Ansah2002; de Haas Reference de Haas2010). Occasionally we find researchers who raise the question of how to define “skilled,” often reminding us that what is skilled in one context may not be considered so in another (Findlay and Gould Reference Findlay and William1989; Salt Reference Salt1997; Milio et al. Reference Milio, Lattanzi, Casadio, Crosta, Raviglione, Ricci and Scano2012; Fiore Reference Fiore, Ruberto and Sciorra2017). There is also a wider definition of brain drain that applies to the reduction of skills in a given geographical area due to migration from rural sectors toward urban areas; in this case the definition of “rural brain drain” emerges (Carr and Kefalas Reference Carr and Kefalas2010).

Many scholars, instead, claim the category should be further refined to include only “key” migrants, the best and the brightest or the outstanding—not necessarily based on their level of education. In fact, in his article in 1970, Baldwin states that these outstanding migrants would be difficult to replace, although there may be dozens of men with the same educational qualifications. He also emphasizes that much of the loss in focus on brain drain is concentrated around these migrants. This concept is carried on throughout the literature by other authors (Sukhatme Reference Sukhatme1992; Dumont and Lemaître Reference Dumont and Lemaître2005; Portes and Celaya Reference Portes and Celaya2013), who consider the key migrants to be of particular concern, not defining them simply as those with advanced degrees but rather as those who have something extra in terms of motivation, capacity, spirit of initiative, and so on. On this last point, it is interesting to note that development economists acknowledged the “selective” nature of emigration. William Arthur Lewis, for instance, highlighted that migrants, given the fact that they move in order to “better themselves,” have a psychological attitude that “sharpens their wit, bringing them into contact with a new environment, and sharpening their critical faculties” ([1955] Reference Lewis1956, pp. 363–364). John Kenneth Galbraith, with the same attitude, stated that in a context of generalized poverty, the more dynamic elements refuse to accommodate to the poverty trap and consider emigration as an escape avenue (Reference Galbraith1979, ch. 8). From this brief review of definitions of brain drain, it emerges that it is therefore also possible to consider the Italian debate for the purpose of deepening this concept, which, in its broadest version, also includes unskilled workers and agricultural workers who represented the majority group of Italian emigration between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The third issue when we examine brain migration is whether it is, indeed, negative or not. Here, as in the debate in the early 1900s, a common conclusion has not been reached and there is also a similar bifurcation regarding the effects of emigration, positive or negative, which is related to the micro or macro approach.

In the 1960s literature, the discussion evolved around the nationalistic approach, where a country’s aim was to maximize its military and economic power, and since the migration leads to a reduction in manpower and the output of the nation is lowered by the amount that the emigrant would eventually contribute, this emigration is seen as negative (Grubel and Scott Reference Grubel and Scott1966; Johnson Reference Johnson1965; Thomas Reference Thomas1967). On the contrary, the microeconomic approach states that, if the emigrant improves his situation and his departure does not lower the income of those who remain, then emigration should be encouraged (Grubel and Scott Reference Grubel and Scott1966). This bifurcation between the nation-state level of analysis and the individual one is another example of continuity in the comparison that we are proposing inasmuch as the results of these analyses are similar. While from the aggregate (macro) approach derives the necessity to measure the economic loss caused by emigration and possibly to set up appropriate policies to counter these effects, from the individual (micro) point of view emigration brings a general betterment of economic conditions, especially for the emigrants themselves.

In the 1970s, much of the literature was focused on ways to restrict educated migration from developing countries to limit damages in terms of the loss of qualified workforce (Blomqvist Reference Blomqvist1986). Some authors suggested that the developing countries, which lose due to the brain drain, need to work on keeping their specialized manpower (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1970). For example, in the case of students who study abroad and do not return, countries should keep in touch with these students and change their approaches to hiring in the home country (Sukhatme Reference Sukhatme1992). As can be seen from various works in the 1970s—many of which were presented at the Bellagio Conference on Brain Drain and Income Taxation—other authors affirm, instead, that in some cases external help is needed and stronger policies should be put into place. They proposed, for example, the taxing of the brain “drained” emigrants to compensate for their loss (Bhagwati and Dellalfar Reference Bhagwati and Dellalfar1972; Bhagwati and Rodriguez Reference Bhagwati and Rodriguez1975; Oldman and Pomp Reference Oldman and Pomp1975). Others, instead, discuss policies that subsidies be awarded for students who return (Kwok and Leland Reference Kwok and Leland1982). Nadeem U. Haque and Se-Jik Kim (Reference Haque and Kim1995) discuss the alternative scenarios of subsidies on education—specifically, higher education vs lower education.

In the contemporary case of Italy, authors emphasize the dichotomy between insiders and outsiders in the labor market. This opposition results from the protection of those who have a job but harms those who are looking for work, especially the youngest, who are offered mainly temporary and unprotected jobs, thereby favoring the emigration of the most qualified young people (Becker, Ichino, and Peri Reference Becker, Ichino and Peri2004). Another issue are Italian labor policies that are unable to keep talents at home and/or to attract foreign brains (Milio et al. Reference Milio, Lattanzi, Casadio, Crosta, Raviglione, Ricci and Scano2012).

We can say that the problems of defining and measuring the costs of emigration, and possibly setting up appropriate economic policies, are still today at the center of the debate.

VIII. ELEMENTS OF CONTINUITY

The debate that developed in Italy between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on the issue of the cost of production of men associated with emigration refers mainly to unskilled workers or workers with low levels of qualification (peasants and workers), which constituted the main demographic group from which emigration was generated in that period. It is worth remembering that in the post-unification period, the levels of illiteracy in the Italian regions were profoundly different and on average very high. At the aggregate level, the percentage of illiterates was still around 50% in 1910, and Italy, amongst western European countries, was the one with the highest illiteracy rates (Woodhouse Reference Woodhouse and Lyttelton2002, p. 216). It is therefore not from this point of view that it is possible to compare the debate of the early twentieth century with the vast literature on brain drain.

On the contrary, what we consider relevant for the purposes of this investigation is that throughout brain drain literature, we can find many of the same contrasts that can be found in the previous debate on emigration and the calculus of the value of men. In fact, the underlying sense of much of the debate is hinged on three key points:

-

(i) lack of appropriate data;

-

(ii) lack of an exact definition (in fact, many authors do not explicate the type of emigrants they are referring to when using the term “brain”); and

-

(iii) the discussion whether brain drain migration is truly negative and for whom.

In both historical periods it has proved very difficult for scholars to define what the sending country loses (in terms of income or wealth) as a result of emigration, and, consequently, it has been found to be impracticable on the whole to define the unit of measurement with which to establish the economic effects of emigration. In other words, an adequate unit of measurement of the emigration costs remains undetermined. The data analysis is not decisive for understanding whether the economic effects of emigration are in favor or to the detriment of the country of departure.

Although, as stated previously, the emigrants themselves were different, unskilled vs skilled, there are other interesting similarities that can be found when examining the evolution of the literature. In both periods the search for an answer to the question of whether or not emigration is beneficial, and to whom, depends greatly on the approach taken. If, for example, we consider Italy as a developing country in the first period, then especially Beneduce’s considerations are similar to many of the authors in the second period examined: emigration is, overall, positive for the countries of origin if we recognize the benefits it contributes—remittances, easing of pressure on home countries’ resources, and, in a certain sense, encouraging the “flow of man goods” (in the brain drain literature this can be seen as the flow of technology).

Also of particular importance in the comparison of the two periods here discussed is the strain of literature that considers the “brains” as something beyond their level of education. Indeed, in using this expanded definition, the migration of these “key” emigrants can be seen in all periods of migration and not only in the most recent one. The study of this type of emigrant proves difficult due to the fact that it appears to be more of a qualitative characteristic, rather than quantitative, and leaves the door open for further research opportunities.

Another common point is the great importance given to the lack of appropriate data to measure the costs of emigration. In both periods, there is a continuous emphasis placed on the need to measure these costs and find an appropriate model, and yet at the same time authors lament a gap in the information necessary to truly make the required calculations.

The literature on brain drain, as we have seen, has the added burden of the vagueness of the definition of the term, which is the hallmark of the entire literature, making it even more difficult to establish who loses and who gains and by just how much.

IX. CONCLUSIONS

The two aims of this paper were: 1) to backdate the roots of the brain drain research field within the literature on the economic effects of emigration, and 2) to highlight the elements of continuity in the struggle for defining a specific cost-benefit analysis referred to emigration, and of designing appropriate economic policies. In this concluding section we propose a possible explanation for the enduring character of the problem encountered during the centuries by economists on the calculus of the value of men.

Our belief is that, throughout this literature, a problem of composition between the micro and macro levels of analysis clearly emerges. The decision to migrate can be analyzed within a neoclassical theoretical context, with individual utility functions and cost-benefit analysis. For example, Coletti sets his analysis of the “psychology” of emigration in these terms. But the effects at the aggregate level do not correspond to the simple sum of individual choices because, as clearly emerges both in the debate of the Italian Liberal period and in the literature on the brain drain, it is necessary to consider other variables such as education costs, the effects generated on aggregate income due to the decrease in the resident population and/or the departure of skilled workers, and so on. Our conclusion is that both the calculation of the value of men regarding emigration and the most recent literature on brain drain reach no conclusive results because of this “fallacy of composition” between the micro and the macro levels of analysis. The issue of the fallacy of composition is as old as the economic reasoning inasmuch as the first recognition of this theoretical problem was proposed by Bernard de Mandeville (Reference Bernard de1714) in his Fable of the Bees, later recalled by John Maynard Keynes’s “paradox of thrift” (see King Reference King2012, pp. 9, 31–32, 41–42). In both cases, the social outcome of individual decisions does not produce an improvement from the aggregate point of view, or, alternatively, it is not possible to determine the behavior of the aggregate variables by inferring it from the behavior of the individual ones. Another interesting outcome, which applies to the economic analysis of emigration, is that when a theory or analytical reasoning produces a statement about an individual (i.e., emigration contributes to the betterment of personal economic conditions), the same statement is not applicable for a population or a nation because of the problem of composition recalled before. Our conclusion is that this methodological/interpretative problem emerges in both seasons of economic thought analyzed in this work.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The author declares no competing interests exist.