Article contents

A strong version of Herbrand's theorem for introvert sentences

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 March 2014

Extract

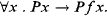

A version of Herbrand's theorem tells us that a universal sentence of a first-order language with at least one constant is satisfiable if and only if the conjunction of all its ground instances is. In general the set of such instances is infinite, and arbitrarily large finite subsets may have to be inspected in order to detect inconsistency. Essentially, the reason that every member of such an infinite set may potentially matter, can be traced back to sentences like

(1)

Loosely put, such sentences effectively sabotage any attempt to build a model from below in a finite number of steps, since new members of the Herbrand universe are constantly brought to attention. Since they cause an indefinite expansion of the relevant part of the Herbrand universe, such sentences could quite appropriately be called expanding.

When such sentences are banned, stronger versions of Herbrand's theorem can be stated. Define a clause (disjunction of literals) to be non-expanding if every non-ground term occurring in a positive literal also occurs (possibly as an embedded subterm) in a negative literal of the same clause. Written as a disjunction of literals, the matrix of (1) clearly fails this criterion. Moreover, say that a sentence is non-expanding if it is a universal sentence with a quantifier-free matrix that is a conjunction of non-expanding clauses. Such sentences do in a sense never reach out beyond themselves, and the relevant part of the Herbrand universe is therefore drastically reduced.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Association for Symbolic Logic 1998

References

REFERENCES

- 1

- Cited by