Introduction

Today’s society is recognised by how professional knowledge is interweaved with social life (Knorr-Cetina, Reference Knorr-Cetina1999: 6). The knowledge society also permeates governing, and a knowledge-or evidence-based policy is a common commitment in the western world (Cartwright et al., Reference Cartwright, Goldfinch and Howick2010). Liberal influence connected governing with knowledge produced by the positive sciences, and the activities of government to facts, theories, techniques, and knowledgeable persons (Hacking, Reference Hacking1981; Rose, Reference Rose1999). The division of knowledgeable persons by professions and epistemic culture created sectorial divisions in governments through the twentieth century, that was further segmented by the influence of neoliberal ideas and New Public management governing tools from the 1980’s (Christensen and Lægreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2004; Rose, Reference Rose1999). Sectorial division, and the parallel recognition of the complexity of many policy issues, has since the beginning of the 1990s caused a need to cooperate and coordinate across policy sectors to achieve integrated policy initiatives (Hajer and Wagenaar, Reference Hajer and Wagenaar2003). However, the combination of knowledge-based policies and the coordination of policies across sectorial units has been found to represent a challenge (Peters, Reference Peters2018). Epistemological outlooks create boundaries that inhibit how knowledge translates and travels (Smith and Joyce, Reference Smith and Joyce2012), caused by civil servants embeddedness in professions, but also by how measuring and evaluation of policy outcome are favoured techniques of modern governing. From a discursive perspective, the formation of policies is a competition over various understandings of socio-institutional reality (Fischer, Reference Fischer2003), materialising in problem definitions reflecting these understandings (Bacchi and Goodwin, Reference Bacchi and Goodwin2018; Rose, Reference Rose1999). This makes studies of discourse and knowledge central within policy studies. Examples include the Fischer and Gottweis (Reference Fischer and Gottweis2012) studies addressing policymaking as part of an argumentative turn in society, focusing on communicative practices in policymaking and how competing actors construct divergent policy narratives when approaching complex issues. Another example is Schmidt’s (Reference Schmidt2008; Reference Schmidt2017) discursive institutionalism that addresses the interactive processes of discourse by which actors in policymaking express ideas embedded in institutional contexts.

Homelessness is an example of a complex policy issue requiring initiatives that range across professional divisions and governmental organisations. Most countries in Europe, the US, and Australia have developed policies with the aim of reducing homelessness (see e.g. Minnery and Greenhalgh, Reference Minnery and Greenhalgh2007), and ten EU member states are identified as having developed national strategies aimed at delivering ‘integrated strategic responses’ to homelessness (Baptista and Marlier, Reference Baptista and Marlier2019, 54). How homelessness is interpreted differently according to institutional contexts has been explored and discussed in research since the category of homelessness was constructed in the 1980s. Discursive embeddedness of those in power to define has moved explanations of homelessness back and forth within an individual-structural dichotomy perceiving homelessness to be caused by either individual lack of skills to maintain a home or a social network, or structural conditions such as low income and a general lack of opportunities (Harvey, Reference Harvey1984; Schön and Rein, Reference Schön and Rein1994). A plethora of studies has applied this structural-individual dichotomy in discussing how policies differ in their conceptualization and approach to homelessness across national borders (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Dyb and Finnerty2016; Fitzpatrick and Stephens, Reference Fitzpatrick and Stephens2013) or across time (Bullen, Reference Bullen2015; Cronley, Reference Cronley2010; Pleace and Quilgars, Reference Pleace and Quilgars2003). However, as observed by Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Collins and Anderson2016, 250), studies of homelessness policies have given little attention to the actual places, spaces and networks through which problematisation in governing homelessness occurs. The policy study tradition addressing how knowledge and discourse represent epistemic barriers in coordination of policies seems not to have influenced homelessness research, and homelessness as a policy issue has rarely been the case of studies addressing the role of knowledge. This study is a contribution to filling this gap, and to bridge the literature on coordination of policies, the epistemic embeddedness of experts, and the social policy issue of homelessness, using a coordinated policy initiative aimed at homelessness in Norway as a case.

As a country labelled a Scandinavian welfare state with wide social and economic safety nets (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), pursuing a leading role in welfare policies (Neumann and Haugevik, Reference Neumann and Haugevik2020), it is a goal of the government that no one should experience homelessness. Homelessness policies have, since 2001, been developed in coordination between the policy sectors responsible for housing, labour and social affairs, health and care, and criminal justiceFootnote 1 , the housing policy sector holding the main responsibility. The Housing for Welfare (HfW) strategy frames the policy initiatives addressing homelessness in the period 2014- 2020, and the paper is based on a study of expert civil servant practices within HfW. The four policy sectors involved are all shaped by a general discourse of governing, but they differ in how professional discourse structures their approach to social policy problems. How do they talk about homelessness? What terms and categories do they activate? What knowledge shapes their perceptions of homelessness as a policy problem and suggested solution? These research questions are explored through analyses of discourse and practice and discussed in light of theories considering the importance of problem definitions and epistemic embeddedness in achieving integrated policies. The findings indicate that all policy sectors seem to recognise their responsibility within a social welfare frame, but despite having cooperated for several years, embeddedness in sectorial discourse and epistemic culture causes diverging problem definitions, and thereby leads to diverging solutions.

The paper proceeds as follows. The first section provides theories considering the knowledge society and how experts and professions contribute to shaping discourse and epistemic cultures. This is followed by a brief overview of NPM and the following reforms, focusing on the principles they provide for orientation in policymaking. The case of study is then presented, followed by a methods section. The empirical findings are presented, and then discussed through the prism of the theoretical lenses, before the paper ends with a conclusion.

Horizontal specialization in a knowledge society

The professionalisation of government that enabled prominent positions in governing for expert figures like scientists and engineers (Haas, Reference Haas1992; Rose, Reference Rose1999) also linked policies with wider discourses of expert knowledge. Interpretation and definition of policy problems, commonly regarded as the first, and most important, stage of a policy circle, are thereby shaped by these wider discourses. How terms and categories are used in problem definitions is important; it provides language for communication that highlights specific issues at the expense of others, it connects a phenomenon-to theories about how a problem may be alleviated (the policy solution), locate responsibility and affect further knowledge production (Weiss, Reference Weiss1989). A problem definition also includes a construction of the target population, creating new social groups through the existence of policies addressing their situation (Schneider and Ingram, Reference Schneider and Ingram1997). Problem definitions become institutionalized, embedded in groups, organisations, and structures, often outlasting the initial conditions that shaped their emergence. They appear as “facts” and contexts to operate within, and they shape the language used for communication (Berman, Reference Berman2013; Smith, Reference Smith2013).

The concept of epistemic community (Haas, Reference Haas1992) captures how groups of professional civil servants share an epistemic embeddedness, shaping their understandings of a policy issue. Epistemic community is defined as “a network of professionals with recognised expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authority claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue area” (Haas, Reference Haas1992: 3). The professionals share a set of normative and principled beliefs providing a rationale for their social action, they share causal beliefs and notions of validity, and a set of practices associated with the problems their professional competence is directed at (Haas, Reference Haas1992). The concept of epistemic culture enables explorations of a broader complexity of what constitutes knowledge (Dijk, Reference Dijk2014). It is developed by studying scientists and moves beyond community by highlighting the practices of gaining knowledge that unites and divides epistemic cultures. Cultural divisions are entrenched in education, research organisations, and systems of classifications, making groups of specialists prone to cultural division by being separated from other experts by institutional boundaries (Knorr-Cetina, Reference Knorr-Cetina1999:2). The notion of an epistemic culture “brings into focus the content of different knowledge-oriented life-worlds, the different meanings of the empirical, specific constructions of the referent (the objects of knowledge), particular ontologies of instruments, specific models of epistemic subjects” (Knorr-Cetina, Reference Knorr-Cetina2007: 364).

Expert civil servants are embedded in epistemic community and culture through education, but also by how interaction between governmental agencies, policy analysts, and experts has increased with the development of a knowledge society. The civil servants turn to – or even participate in – scientific communities to resolve policy dilemmas, resulting in knowledge-based social systems surrounding institutionalized ideas where experts from both outside and inside government are included (Fischer, Reference Fischer2003: 33). The concepts of epistemic community and culture highlight how civil servants do knowledge-based policymaking, and what concepts unite or divide them in cooperation. Examples include what types of data are used in obtaining knowledge, what classifications are used in gathering data, and what epistemic strategies are used to validate and check the consistency of information. In the case studied here, the four involved policy sectors are in different ways connected to scientific environments providing knowledge for policymaking by recognised methods. Examples include how knowledge in the health policy sector is provided by the Norwegian Institute of Public health, responsible of “knowledge production and systematic reviews for the health sector and knowledge about the health status in the population, influencing factors and how it can be improved”Footnote 2 . The housing policy sector mainly obtains knowledge for policymaking through commissioning of research, such as the survey of homelessness performed every fourth year, or evaluation of policy initiatives.

Governmental reforms and knowledge tools

The governmental reforms commonly referred to as New Public Management (NPM) were inspired by neo-liberal ideas of governing and developed in most European bureaucracies in the 80s (Rose, Reference Rose1999). NPM reforms were introduced to enhance efficiency in service delivery by emphasising management within individual organisations and top-down control, values originating in private sector principles of professional management: explicit standards, managing by results, and value for money (Kjær, Reference Kjær2004). Performance measurement is the most common tool (Boswell, Reference Boswell2018: 1): other examples are national guidelines, standardization (Danielsen et al., Reference Danielsen, Klausen and Stokstad2019), and evidence-based methods (Cartwright et al., Reference Cartwright, Goldfinch and Howick2010).

The central element of the NPM-tools is that they involve quantification. Knowledge in numbers entails a range of advantages in governing, and at the same time the use of numbers displays an effort to incorporate scientific evidence into policy decisions. Quantitative measures turn the qualitative, social world into information and enable control, evaluation and comparison of complex social phenomenon. Numerical pictures create clarity, making complex phenomena comprehensible through simplification and classification. Quantification thereby offers a shared language that transcends other forms of differences, accommodating for coordination of activity across cultural (Espeland and Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens2008: 402), social, geographical or political distances (Porter, Reference Porter1996). However, there are also significant pitfalls involved in quantification of social phenomena. Numbers do not merely inscribe a pre-existing reality, but rather constitute it. Numbers are linked to specific problematisations: if to problematize a social phenomenon-within governing requires it to be counted, then what is counted is what is problematized (Rose, Reference Rose1999). Classification of social phenomena transforms all differences into quantity, and thereby reduces the complexity of a social phenomenon-but the reduction mirrors the interpretations of those who make the reduction and the statistical categories again remake what it measures (Espeland and Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens2008).

The implementation of ideas and tools associated with NPM have caused a tendency for governments to de-emphasise horizontal management (Peters, Reference Peters2018). As a response, several coordination models have developed to accommodate for policy integration. Policies aimed at homelessness in Norway provide an example of a coordinated initiative in post-NPM reforms attempting to attend to numerous and sometimes conflicting ideas, considerations, demands, structures, and cultural elements at the same time (Christensen and Lægreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2011). Tosun and Lang (Reference Tosun and Lang2017) distinguish between governance centred approaches focusing on policy processes and implementation, and government-centred approaches focusing on coordination and the institutional and organisational dimensions. The case of study here resembles a government-centred approach, and a whole of government (WOG) model (Tosun and Lang, Reference Tosun and Lang2017), described as ‘public service agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues’ (Kickbusch, Reference Kickbusch2010: 12). WOG models depend on information sharing and knowledge management, and comprise the developments of inter-departments and inter-administration coordination. Commonly applied tools are inter-ministerial or inter-agency collaborative units in combination with measuring of performance (Tosun and Lang, Reference Tosun and Lang2017). However, several studies of coordinated government initiatives have found that the tools securing top-down control continue to play a central role in governance despite post-NPM reforms. The use of targets, and measures of to what degree these targets are reached, is a way of signalling order and control (Boswell, Reference Boswell2018), and are still perceived as important in meeting the expectations of appropriate modes of governing. Measuring of performance is especially valued when dealing with complex issues, despite how studies have shown measuring of results according to sectorial divisions negatively affects the coordination of policies by causing collective goals to be ignored (Øverbye, Reference Øverbye2013). How this also applies in the Norwegian case will be illuminated in the empirical section.

A coordinated effort to fight homelessness

Homelessness in Norway is defined as

[…] a person who does not own or rent a home, and is left with coincidental or temporary housing arrangements, who temporarily stay with close relatives, friends, or acquaintances, or is under the care of the correctional services or an institution, due for release within two months and without a home. People without arranged accommodation for the next night are also considered homeless (Housing for Welfare, 2014: 31).

This definition was made for the first survey of homelessness in 1996 (Ulfrstad, Reference Ulfrstad1997). The same survey has been performed every four years since 1996: the respondents are municipal employees, typically social workers, providing knowledge about persons they know to experience homelessness according to the definition. The survey categorises the data according to length of experienced homelessness, type of temporary accommodation, education and source of income. The respondents are asked to provide information about why homelessness has occurred, here the categories span from “has been evicted”, “loss of income” and “released from jail” to “the person has a mental illness” and “the person is addicted to drugs”. The survey of homelessness is important by how it provides language structuring practices of policy making, and the categories also illustrate how homelessness is recognized as a complex policy issue. The HfW-strategy recognizes this complexity, a central objective is to “gather and target the public effort with the aim of securing safe housing for all” (Oslo Economics, 2020: 4). From 2018, initiatives securing adequate housing for persons with dual diagnosis were given priority (Initiative plan HfW, 2018–2020). Despite these efforts, the last survey of homelessness counted 3, 325 homeless persons (Dyb and Zeiner, Reference Dyb and Zeiner2021).

Methods

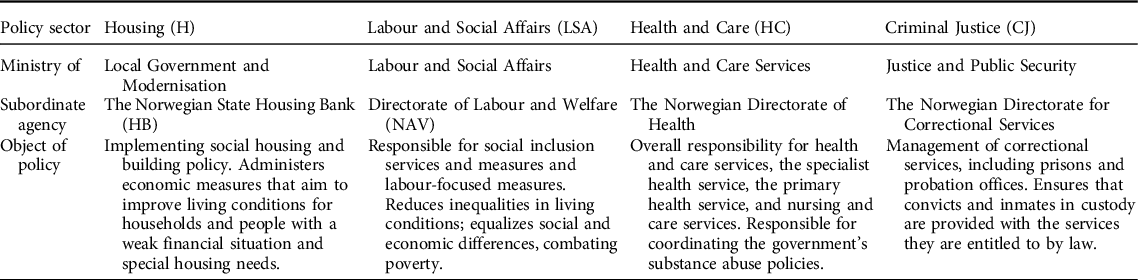

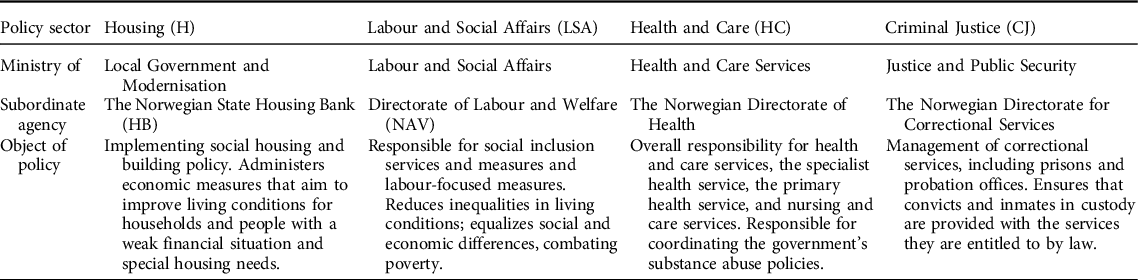

The study is based on data material obtained by qualitative methods. Throughout 2019, I observed meetings, performed interviews, and collected text material in arenas where policymaking addressing homelessness was discussed. Table 1 shows the policy sectors involved in the initiative and their object of policy. In the presentation of methods, empirical material, and discussion, the abbreviations from this table will be used.

TABLE 1. Policy sectors involved and object of policy

The talk material consists of:

-

Semi-structured group interviews within three policy sectors (HC, LSA, and CJ) at the sub-ministry level, performed in the informant’s workplace, lasting approximately 90 minutes. The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

-

Observations in 11 meetings discussing current and future policy programs aimed at homelessness, each lasting 1.5–2 hours. Five meetings had the attendance of civil servants representing the housing policy sector at the sub-ministry level. Six additional meetings included civil servants from HC, LSA, and CJ. In one of these six meetings, civil servants at the ministry level attended in addition to those representing the sub-ministry level. Six meetings were recorded on tape and later transcribed, and five were recorded in writing. I always introduced myself at the beginning of meetings, but the data material was obtained by passive observation, I did not participate in the interaction.

-

All participants gave their consent to participate in the study. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data granted ethical permissions for this study.

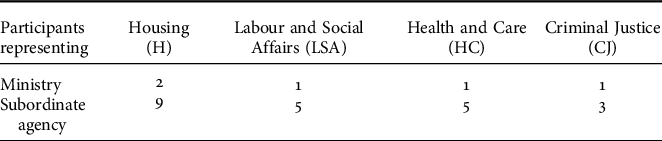

Twenty-seven civil servants are represented in the talk material. Of these 27, there are 12 civil servants who are recurring in different data sources, as they represent the most central agents in their policy sectors’ approach to homelessness. Table 2 shows numbers of participants by sector and units.

TABLE 2. Numbers of participants by sector and units

In the arenas where interactions were observed, the informants also very generously shared written material produced before or following the meeting. In addition, policy strategies, allocation letters, web pages, and research reports were part of the data material.

The analyses of data were performed by approaching distinct dimensions in talk and text: argumentative, evaluative, and dramatizing statements about what causes homelessness and how it may be resolved, and what terms and categories reoccur in discourse. The data material was sorted manually according to these dimensions, starting with the talk material and followed by an exploration of the surrounding text material. After establishing central dimensions in talk that seemed to structure discourse, epistemic strategies and empirical procedures were identified. Both processes of analysis were implemented within and across policy sectors. The analytical approach was inspired by the sociology of knowledge approach to discourse (SKAD) (Keller, Reference Keller2011; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Hornidge and Schünemann2018) and Knorr Cetina’s (Reference Knorr-Cetina1999, Reference Knorr-Cetina2007) approach to epistemic culture.

As the aim of the analyses is to identify discourse, the systems of meaning production structuring the practice (Dunn and Neumann, Reference Dunn and Neumann2016) of the expert civil servants, the inclusion of published textual sources in the material for analyses was important. Governmental textual sources represent a materiality aspect of discourse, important in conveying the discourse of a policy sector. Quotes and excerpts from both talk and text are used in the empirical section as examples of what is interpreted as the general discourse or epistemic culture. Textual sources also provide possibilities to adjust for potential bias caused by an imbalance in the talk material, or my own embeddedness in discourse. Data obtained by observation in meeting entail a risk of capturing the practices of the most talkative civil servants and missing out on the quiet ones. My own situatedness (Neumann and Neumann, Reference Neumann and Neumann2018) is influenced by former experiences of being a participant in policymaking at ministerial and sub-ministerial levels, as well as an employee in a shelter attending to the needs of persons experiencing long-term homelessness. These experiences make me more familiar with some elements of the discourse than others, and I have attempted awareness to this potential bias all through the process of data collection and analyses.

Empirical section: Four ways to talk about homelessness

As shown in Table 1, the policy sectors cooperating in policymaking target different objects of policy. Their objects and aims connect them to epistemic communities and cultures, where categories and vocabulary are institutionalized and taken for granted. I now present the empirical material and display how the policy sectors talk and write about homelessness, focusing on what emerge from the analyses as the most relevant issues to address. In the following discussion these variations will be addressed.

The section is divided into four subsections according to policy sector. To clearly illustrate how epistemic embeddedness shape interpretations differently I have included how the policy sector perceives Housing First (HF) at the end of each section. Housing First is a so-called standardized model of providing housing and services based on the argument that RCT studies have proven it to be an effective model (Tsemberis, Reference Tsemberis2013).

Housing as a basic need and welfare pillar

When talking about persons lacking a home within H, homelessness is the term employed as a category and target group, used according to the definition referred page 7. The occurrence of homelessness is mainly described by reference to the most recent survey of homelessness (Dyb and Lid, Reference Dyb and Lid2017), and the categories correspond to those used in the survey. Below is an example from talk:

“We had a dramatic decline in 2016, no other country has had a similar development. We have a larger share staying in institutions, and it was not changed (with reference to the survey of 2012). We do not see the same decline in the share of persons staying in temporary housing; it increased slightly. The share sleeping rough has also increased, and we still have many staying with friends and acquaintances”.

The example illustrates a general feature of how all descriptions and discussions of homelessness were structured. The categories developed with the aim of counting homeless persons in the regular survey provide vocabulary and knowledge to talk about homelessness. The survey, and its system for measuring, is described by the civil servants as crucial in their development of policies. The possibility of measuring also affects who is considered the most potential target group for policies. In an intern H-meeting, one of the senior advisers argued that “It’s those who stay in temporary housing who should be the target group; this is the group possible to measure. That is difficult considering those who stay with family and friends”.

References to how other countries approached homelessness, and their population of homeless, were frequent, especially considering their access to statistics for measuring. This was explored and discussed using the same categories as those applied in the Norwegian context, here illustrated by an example from a presentation in a meeting:

“Norway has a greater proportion of long term homeless than Sweden and Denmark. Norway had many young people experiencing homelessness, but the numbers decreased from 2013-2016. Finland has managed to decrease the number of persons sleeping rough, in Norway we have seen an increase”.

The civil servants also refer to knowledge obtained in international conferences and by participation in international networks, considering housing models, but also alternative methods of measuring. The European typology of homelessness and housing exclusion (ETHOS) is a reoccurring reference in text and talk, a typology launched in 2005 “as a means of improving understanding and measurement of homelessness in Europe, and to provide a common language for transnational exchanges on homelessnessFootnote 3 .” A model imported from the international context is Housing First (HF), and attention to this model is significant. Examples include how the Housing Bank has developed a manual for the use of HF in Norway and how senior advisers engage in international HF Networks. The quote underneath, from the introduction to the manual, shows how the housing sector emphasises the right to housing as a fundamental principle of Housing FirstFootnote 4 :

Housing First turns around the idea that homeless people must “deserve” their own home, or must show that they are “ready for” or even “worthy” of a home by first going through treatment to, among other things, become drug-free. Housing First works according to the principle of housing as a basic need that must be met before one can embark on more complex processes such as rehabilitation and treatment.

Simultaneousness in services

In LSA, ‘homeless’ is not used as a category in talk or text – the non-use of this category was even emphasised several times in talk. A broad conception of the target group as “service recipients” dominates talk and text, and some of these persons need services to secure their housing situation. However, this is recognised as a challenging task, as described by a civil servant: “The complexity in the situation of service recipients experiencing homelessness might also be the greatest challenge for the services and the way we govern services in Norway. The service providers struggle to position themself in relation to some of these persons”. Norwegian Social Services Act (2009) was a frequently used source of reference in LSA. After the group interview, a senior adviser forwarded me the objects clause of this juridical framework to illustrate this complexity in the policy objectives of LSA. “The purpose of the law is to improve the living conditions of the disadvantaged, contribute to social and economic security, including giving the individual the opportunity to live and work independently, and promote the transition to work, social inclusion and active participation in society” (Norwegian Social Services Act, 2009). It was not clear which one of the components should be addressed first in order to support the service recipient, as illustrated in this discussion among three participants in the interview:

A: “Work and securing income are the most important social housing instruments”

B: “Housing is also important. If you try to include someone in work and activity, and the housing conditions are not well, or they lack housing, it is a challenge to make it work”.

C: “Conversely, we often see that work and activity stabilize the situation. This makes parallel processes important”.

Statistics and standardized models were other main references. The informants were reluctant to comment on issues when they lacked a foundation in statistical sources or evaluations of implemented models. LSA gather statistical data according to the categories of service provision: care services, municipal housing and temporary housing, and social assistance. Temporary housing is a service providing roofs over the heads of rough sleepers, and it also represents a situation of homelessness according to the definition. Statistics provide aggregated numbers of how many stays in temporary housing a municipality supplies within a period. Knowledge obtained from standardized models, implemented and evaluated in Norway or in other contexts, was referred to in talk as well as text when addressing how to ensure simultaneousness and totality in service delivery. Housing First is a reoccurring reference also in LSA, praised in both talk and text by how using the model accommodates for knowledge transfer and learning from international research results. Model fidelity, enabling randomised control studies and measuring of results, are described as very important for knowledge development considering what works in the pursuit to remedy homelessness.

Care for gradual development

The term person or patient is used when addressing the problem of homelessness in HC, reflecting an emphasis on individual needs. A statement from a senior adviser representing HC in a cross sectorial meeting illustrates this: “It’s not the lack of housing units that is the problem; it’s rather the lack of suitable housing, where the services are adjusted to the need of the person living there. If the services are wrong, the housing unit may turn out wrong as well”. The focus on individual needs is also reflected in guidelines, such as the web-based National Knowledge-Based Professional Guidelines (2017), where it is described how: “Some patients have, for different reasons, difficulties in securing or establishing a stable and permanent housing situation, and many lack the competence and knowledge in turning it into a home. Not everyone is in a position where separate housing is the best alternative”. The guideline is repeatedly referred to in talk, and represents the national health authority’s perception of what can be categorized as adequate professional praxis and interpretations of the legal framework, developed to reduce unwanted variation and promote good quality in health and care services.

The term daily living skills is used in talk to capture the lack of competence and knowledge described in the guideline, but the term skills also points to the possibilities of development. Below is a quote from a senior adviser at the sub-ministry level describing how to approach a person who has an experience of long-term homelessness:

“You must ask what this person’s need is right now. And what needs will he or she have in the future? You will find that several do need assistance; they are unstable. It is important that we ask ourselves, how may we assist this person in the best possible way? Some will need assistance part of the time or need a transfer period to enhance daily living skills and adjust to individual living. If you accommodate the services to the user, then the daily living skills increase considerably. You know, to live independently is actually quite advanced”.

Other sources that appear as important in providing knowledge are the tool Users Plan Footnote 5 and evaluations of standardized models. Users Plan is a tool mapping each service recipient’s situation according to housing, economy, social network, and more, in addition to services received. The tool categorizes housing as a service, separating “housing service with personnel” and “housing service without personnel”. Knowledge from this tool is aggregated, and shapes the discourse within HC. Knowledge developed from evaluation of standardized models is perceived as leading to so-called evidence-based practice. Housing First is an example of a standardized model, encouraged by HC, supported by available grants for municipalities. In talk, Housing First is described as a tool to secure the individual approach. Below is a quote from the interview:

“Housing first is an approach to increase individuals’ daily living skills, period. One may comment on the ideology that one should live in scattered housing, but that is not the important thing. The most important thing is that you approach each individual and ask, how may your daily living skills increase? On your premises? How can you become the boss in your own project?”

Motivation for social inclusion

The person or inmate is the term categorising the person addressed by policies within CJ. In talk and text, the experience of homelessness is connected to criminal activity, specifically the use of drugs, described by one of the informants as: “This is the elephant in the room, the issue that is not discussed: homelessness is connected to criminal activity. If you do not end the criminal activity and use of drugs, it’s not sure that it’s easy to live in a regular housing unit”. Involvement in the black economy is one of several factors associated with criminal activity that is emphasised in talk and text. When a person performs most economic transactions within a black economy, economic planning is difficult, something which is needed to finance a stable housing situation. The required long-term planning associated with the white economy reduces the motivation to move from the black to the white economy. How the lack of motivation affects the process of securing a housing situation was clearly expressed in the interview: “What do we do with those who are not motivated? It is hard to contribute to establishing housing for someone who does not want it; they do not feel like it”.

Social connectedness was also emphasised as an element affecting the possibilities of exiting homelessness, by how housing enables the risk of loneliness inside the unit and conflicts with neighbours outside. This risk was described as a contribution to anxiety and reduced motivation to obtain housing. Based on this notion, the expert civil servants in CJ emphasise the need for a transfer period between imprisonment and freedom. Daily living skills is a central component, here exemplified in an excerpt from the conversation between two informants in the interview:

A: “Earlier we said housing, but we need a more staircase-like model. It is easier to move on from transfer housing. It is a feeling of distaste connected to entering a relationship of rental housing; it is smart to create a transfer situation”.

B: “And we do lack a system to test daily living skills, a system where there is a mid-way station, where you can stay for three months. During this time, you have to decide how to live and reside, and after the three months, we will find a suitable place”.

The ongoing National Strategy for Reduced Recidivism to Crime (National Strategy, 2017–2021) addresses the concept of a slip zone, referring to how the responsibility of securing the rights of citizens slips between governing units. This notion of a slip zone is also prominent in talk: it is described as causing a challenge in securing suitable services to inmates ready for release. Housing is listed as an essential component in securing an adequate living situation. A central source of data providing knowledge about the situation of the convicts is the Needs and resource mapping in the penal care (BRIK). An inmate’s former and future housing situation is mapped, and it is made known whether there is a need to initiate measures to keep a housing unit during a prison stay or obtain one during the sentence. BRIK is also referred to as a knowledge source, providing information about what elements the correctional services must address. Motivational interview (MI) is highlighted by the civil servants as an important method to achieve a successful release. In the web page describing the activities of the CJ-sector the recommendation of MI is made with a reference to summaries of research findings: “More than 200 RCT studies and several meta-analyses have shown that this method works” (Farbring, Reference Farbring2010). However, the Housing First model, central in the three other policy sectors, is not mentioned in either talk or text.

Discussion

The empirical section shows how the interpretations of experiences of homelessness differ between the policy sectors shaped by a wider epistemic community. They relate to diverging sources of empirical material in their arguments, obtained by different methods. In H, ‘homelessness’ is the central node of discourse, further structured by the knowledge obtained through the survey, in addition to international sources applying similar evaluating methods. LSA secures that services are provided to the citizen according to law. How they approach the problem of persons experiencing homelessness is structured by juridical framework, in addition to an idea of complexity approach and standardized models supported by knowledge obtained by RCT studies. The discourse in HC differs from both H and LSA, by being dominated by an emphasis on individual adjustment of health and care services. HC’s problem definition is centred around the health situation of persons experiencing homelessness, where gradual recovery is perceived as the solution, combined with a need to let the persons experiencing the situation define their needs. In addition to valuing the knowledge of each patient, HC refers to professional guidelines reflecting national and international research within the health and care discourse, and RCT studies that address the effect of services are part of this knowledge base. CJ emphasises the cultural embeddedness of those who experience homelessness, structuring explanations of homelessness as lack of motivation to confirm to mainstream culture. CJ mainly relies on data gathered within their own system and their experiences working with transfers from imprisonment to freedom. Both sources reflect the categories within their discourse.

However, some elements of epistemic culture also enable policy integration. Measuring by numbers is a favoured technique of NPM (Rose et al., Reference Rose, Barry and Osborne2013), turning complex social phenomena into numerical pictures makes them comprehensible, and accommodates for cooperation across cultural distances by providing a common language (Espeland and Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens1998, Reference Espeland and Stevens2008). There are several examples of this in the empirical material. The survey of homelessness that structures the discourse of the housing sector categorise according to issues such as mental illness and drug abuse, and thereby represents a bridge to the H- and CJ-policy sector. The number of persons staying in “temporary housing” is also measured in the survey, and the same term is applied in the legal framework structuring the discourse of LSH.

However, as described in the theoretical section, quantification of social phenomena is also prone to significant pitfalls. Quantification involves a transformation of all differences into quantity by reducing the complexity of social phenomena, and what is counted reflects the problem definitions of those making the reduction (Espeland and Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens2008). This means that what seem like objective categories, accommodating for cooperation across epistemic communities, obscure how discourse fills the terms differently with content. The empirical material shows examples of how even simple terms and categories contain different meaning, and how models used for standardization are understood differently. The term housing is an interesting, and in this case very relevant, example. In the housing policy sector, housing seems to mean separate housing units, regulated by juridical housing contracts, and it is seen as the most important element in a person’s life. LSA seems to partly share this idea, but at the same time housing is seen to be equated with work and activity. Within HC, the category of housing seems to be part of a broader category of services that are provided to the individual according to needs. Within CJ, housing is part of the white economy and a normal lifestyle that the inmate is not always motivated to obtain. This means that when these policy sectors agree on the importance of housing, the word contains different meanings according to discursive embeddedness. The differences in the use of housing also illustrate that even if the idea of the responsibility of the welfare state is similar, the attention to the individual citizen agency varies. The use of “daily living skills” provides a concrete example. HC and CJ activate this term when evaluating the problem of those experiencing homelessness, pointing to the individual competence in managing daily life as expected by the mainstream surroundings. HC and CJ also suggest a “staircase model” of housing as a solution, providing the individual with the opportunity to enhance daily living skills gradually with support. These terms are not used in H and LSA discourse; immediate settlement in permanent housing units is perceived as the appropriate solution, supported by the needed services. The policy sectors’ approaches to Housing First reflect these diverging discourses considering the role of housing, services, and the individual. As shown in the empirical section, H emphasises how the model ensures that a permanent housing situation is secured “first”. LSA understands Housing First as a way to secure simultaneous services, and HC sees it as a model that secures the individual’s need for appropriate care. In CJ, Housing First is not a theme either in talk or text.

Whether these discursive differences at the national level cause consequences influencing the lives of homeless persons are not studied in this project. However, regardless of how Housing First is communicated as a standardized model, evaluations of HF-projects in Norway find substantial variance in what each of the projects are offering to the homeless population (Skog Hansen, Reference Skog Hansen2017; Snertingdal, Reference Snertingdal2014). The differences relate to how the projects are developed within the municipal units responsible for either health care or social housing (Skog Hansen, Reference Skog Hansen2017), indicating that the diversity in discourse at the national level is reflected at the local level, and causes consequences experienced by citizens.

Conclusion

This study provides insight in how knowledge and discourse shape interpretations of a social problem, and how this represents a barrier in an integrated policy initiative to end homelessness in Norway. There is no simple structural-individual divide, as often identified in homelessness policy research (e.g. Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Dyb and Finnerty2016; Pleace, Reference Pleace2000), but rather differences in discursive structuring of the phenomena in question, leading to various problematisations and thereby also solutions. As found in other studies (Espeland and Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens1998; Øverbye, Reference Øverbye2013), the clarity and precision brought about by management tools securing top-down control also secures knowledge development within sectorial discourse, inhibiting a common perception across sectorial borders. In the case of study, several central categories and standardized tools are employed across the sectorial boundaries, but even in these issues epistemic embeddedness causes different interpretations, as even the term housing seems to contain dissimilar meanings. In this study, I have not encountered discussions of content or interpretations of categories in the empirical material; the differences appear as silent epistemic barriers, shaping what knowledge further fuels the discourse. The use of these terms thereby contributes to obscure the differences, rather than integrate the policy initiatives. The findings of this study underline the importance of studying discourse in knowledge societies; it is through terms and categories applied in practice that knowledge is constructed and obtained.

The implications of these findings are of relevance in integrated policy initiatives addressing homelessness, and there are identified ten such initiatives within the EU (Baptista and Marlier, Reference Baptista and Marlier2019), but also considering coordination of policies in general. Quantitative categories and standardized models are deliberately used to accommodate for cooperation across policy sector, but if they contain different meaning, the goal of integrated approaches is not obtained.

Competing interests

The author declares none