Introduction

In the United Kingdom (UK), around one in four adults is thought to be living with a mental illness (Mental Health Foundation, 2019). There is a significant employment gap between the general population and people with mental illnesses (OECD, 2012), and in 2014, 1.1 million people in the UK cited mental ill-health as the primary reason for their social security claim: higher than any other category of health condition (Moncrieff and Viola, Reference Moncrieff and Viola2016). The salience of mental illness as the primary reason for claims appears to be a trend that is increasing over time (OECD, 2012; Banks et al., Reference Banks, Blundell and Emmerson2015).

The main social security payments available in case of episodes of ill health for working age adults in the UK are Employment Support Allowance (ESA), Universal Credit (UC) and the extra-costs benefit Personal Independence Payment (PIP), the latter being designed to support individuals with any additional financial outlays in terms of care or mobility needs that arise as a result of their health condition (DWP, 2016). Eligibility for each benefit is currently determined by a functional assessment, either a PIP assessment or a Work Capability Assessment (WCA) for ESA and UC. Whilst the WCA and PIP assessments differ in their focus, the former aiming to assess ability to work and the PIP assessment designed to explore the need for additional financial support as a result of a health condition, the underlying assessment approach is similar (House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee, 2018). Functional assessments seek to determine eligibility by focusing primarily on the impact of the health condition on the person’s day to day functioning, rather than on the health condition itself (DWP, 2016).

Claimant satisfaction with functional assessments has been mixed (Gray, Reference Gray2014; Shefer et al., Reference Shefer, Henderson, Frost-Gaskin and Pacitti2016; Work and Pensions Committee, 2018) and concerns have been raised that mental health conditions in particular are not well-suited to this style of assessment. This is because mental illnesses are often episodic, not always well-understood and functioning can fluctuate unpredictably (Callanan, Reference Callanan2011; Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2016). This may be reflected in practice; claimants of Disability Living Allowance with a psychiatric condition are 2.4 (95% CI: 2.36, 2.44) times more likely to be turned down following a new functional eligibility reassessment when transitioning to PIP than claimants with some non-psychiatric conditions (Pybus et al., Reference Pybus, Pickett, Prady, Lloyd and Wilkinson2019).

Although there are potential concerns about how well functional assessments are meeting the needs of claimants with mental health conditions, academic research exploring experiences of eligibility assessments specifically from the perspective of this claimant group has so far been limited. Some respondents with mental health conditions have been included where the focus of research is on experiences of the welfare system and welfare reforms (see for example, Garthwaite, Reference Garthwaite2015; Patrick, Reference Patrick2017; Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Jones, McNeill, Scullion and Stewart2018) but this research does not focus specifically on eligibility assessments. With the exception of a report by the charity Money and Mental Health (2019) and a recent study on the impact of conditionality (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Scullion, Jones, McNeill and Stewart2019), each of which exclusively focus on claimants with mental health conditions, studies that do explore experiences of eligibility assessments often use broader samples of claimants with health conditions and disabilities, in which people with mental health conditions may or may not be included. This means, despite predictions that functional eligibility assessments may be problematic, the existing evidence is somewhat disparate.

A greater understanding of experiences of functional assessments for people with mental health conditions is urgently needed to ascertain the potential repercussions of Government plans to explore the possibility of introducing a single eligibility assessment for ESA, UC and PIP (Rudd, Reference Rudd2019). Given the potential impact in this scenario for the eligibility assessment outcome to influence income across a range of benefits, rather than just a single benefit, it is important that the process is equitable across the different health conditions of potential claimants. This article reports on findings from a series of interviews focusing on experiences of eligibility assessments for claimants with a range of different mental health conditions.

Methods

Exploring lived experiences is increasingly recognised as a key tool in social policy analysis, giving voice to marginalised individuals and having the potential to provide detailed knowledge of the impact of policies on those they affect (McIntosh and Wright, Reference McIntosh and Wright2019). To investigate the impact of functional eligibility assessments on social security claimants with mental health conditions, eighteen semi-structured interviews were completed between January and April 2017 with individuals experiencing mental illness who were claiming either ESA, UC and/or PIP in Leeds, a large city in the north of England. The topic guide covered experiences of the claims process and the relationship between mental illness, the claiming of health-related income benefits and stigma. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee at the University of York on 28th November 2016.

Participants were service users of organisations and charities with a remit of offering social support to people with mental health difficulties. This recruitment route was selected because it was likely to include individuals who were living in the community, experiencing a period of relative stability in their mental health and accessing social security in some form. In addition, as only a comparatively small number of individuals receive formal support for their mental health difficulties through psychiatric services – for example, only 4.5% of the UK population were in contact with secondary mental health services in 2017-18 (NHS Digital, 2018) – a clinical population may only include those with more severe mental health conditions, therefore limiting potential variation in experiences.

Recruitment and interviews were carried out by KP, a registered mental health nurse, as part of her doctoral research. Potential participants were identified by consulting with organisation staff; the desire to recruit individuals with a range of positive and negative experiences of the claims process was emphasised to ensure a broad representation of views. In the first instance, participant information sheets and posters were distributed at staff meetings for each of the organisations involved in the research.

Thirteen participants were recruited by staff members from their own caseloads. A further six participants were directly recruited by KP following an invitation to discuss the research at a community support group. In this instance, staff members were notified of interested individuals by the researcher and after the session had ended separately confirmed with the person their wish to participate in order to limit pressure from the presence of the researcher. One participant was recruited by word of mouth after their partner participated in the study. After registering an interest, each of the participants was provided with written information about the study and given forty-eight hours to consider their involvement. Contact was then made to ascertain whether the person wished to participate and to answer any questions. No individuals declined to participate at this point, but two individuals did not subsequently attend an interview, one due to a family bereavement and the other did not provide a reason, leaving a final sample of eighteen participants.

Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview and the right to withdraw from the study at any time was emphasised. Interviews were audio-recorded and took place at a combination of organisation premises (n=8) and, where enough information was known about the person to facilitate adequate risk assessment, at home addresses (n=8). One interview took place in a general hospital setting and another in a coffee shop, as these were the locations most convenient for the person. All interviewees were provided with a £10 cash incentive for participating. The incentive was agreed in advance with service managers in line with standard payments offered for service user participation in focus groups and service improvement activities of around one hour duration.

Data was transcribed verbatim by KP and analysed in Nvivo using a thematic analysis framework (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; QSR International Pty Ltd, 2015). Following initial familiarisation of the data, line by line coding of the transcripts was undertaken and themes were allowed to emerge inductively from the data (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). These were discussed and refined throughout the analysis stage. The themes presented in this article relate specifically to experiences of eligibility assessments and the claims process, other findings are reported elsewhere (forthcoming).

Findings

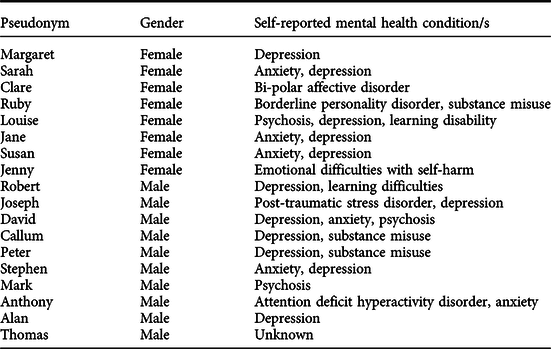

As no new themes appeared to be emerging from the data at around the fourteenth interview, recruitment continued only to achieve an adequate distribution of demographic characteristics. The final sample consisted of ten males and eight females, with an age range of 25 to 60, experiencing illnesses across the spectrum of common and severe mental illness.

The mental health problems described in the sample were self-reported: however, participants typically stated that they had been provided with their diagnosis by a healthcare professional such as a general practitioner or psychiatrist. One participant was unable to provide a clinically recognisable diagnosis but stated that a healthcare professional had described her symptoms as ‘emotional difficulties with self-harm’. A further participant, whilst acknowledging he did experience difficulties with his mental health, declined to provide a specific diagnosis. The sample had a high level of co-morbidity with participants generally reporting more than one mental health diagnosis or difficulty. Table 1 provides details for each individual participant, alongside pseudonyms.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Claimant journeys

Out of eighteen individuals in the sample, eleven had been turned down for one or more health related income benefit, either ESA, PIP or UC. Of these eleven participants, four had appealed the decision and all had been successful in having their benefits reinstated, a further participant was in the process of appealing at time of interview. Seven participants reported that the process of accessing benefits had been acceptable, five of whom had attended their assessment with a healthcare worker or had written evidence from mental health services to support their claim.

It was not possible in the study to independently assess baseline level of functioning; however, there did not appear to be a link in this sample between a greater likelihood of success in receiving a financial award and the levels of functioning described by participants. Louise, for example, who at the time of her PIP assessment had recently left twenty-four hour supported accommodation, was receiving intensive community support and had a longstanding diagnosis of schizophrenia alongside a learning disability, was unsuccessful. Alan, however, who was in part time work and described himself as relatively able most of the time, succeeded in his claim. Regardless of the outcome of the eligibility assessment, the claims process was frequently difficult. Sixteen participants described experiencing stress and anxiety, whilst three reported suicidal thoughts.

Susan: It’s very daunting [attending an assessment] because obviously you hear on the news really horrific things of people being put back to work and you think, well, if they’re doing that to them they’re going to do that to me. So you’ve got those sort of fears.

This often related to preconceptions about the assessment and to the anticipation of a negative outcome. Multiple participants reported symptoms of distress directly related to attending a face to face appointment, such as becoming tearful, anxious or being unable to leave the house without the intervention of family members. As well as possibly exacerbating existing mental health difficulties, this may increase the potential for under-claiming as Alan describes:

Alan: For the assessment I was ill, I was sick during the interview…because it was so nerve-racking. I’ve heard so many bad things about, they call it ATOS or something and I thought “oh God almighty”. At one stage I was just going to abandon it and think well yeah it’d come in handy but I don’t need this extra money that bad to put myself through that.

Once at the face to face assessment, experiences in the sample were varied. For some, the assessment was a much more positive experience than their preconceptions had led them to believe, whilst others described feeling judged and disbelieved.

Sarah: I had them who assess you at a medical place? I don’t know what they’re called but yeah, she was really nice.

Jenny: There was a lady sat in front of the desk and two chairs at the side of me. She was eyeballing me like a hawk.it were really nerve-racking.

Assessing eligibility

Both the WCA and PIP written and face to face eligibility assessments provide space for discussing the impact of mental health conditions on functioning but one of the key themes we found was that most participants perceived their assessment as focusing overwhelmingly on physical health.

Jane: They gave me no points at all because I could turn a light switch on and off and I were well dressed and presented. I thought it were an absolute disgrace to be honest with you…So do they expect people to turn up in their pyjamas, is that what they expect? Then do they pass you straight away? It’s just because when I do go out, I always like to look nice and just because I made an effort, you get put down for it.

This meant that participants frequently viewed the questions they were asked as being irrelevant or as not offering the opportunity to give a full representation of how they were affected by their mental health condition.

Susan: You know “can you lift a cup, can you do this” I mean yeah, I can cook, I can clean, I can budget and all those sort of things. But what I can’t cope with is the emotional side of things, interactions with others, like going to appointments, anything where you have to be physically touched. And obviously that all stems from situations that I faced in my life and that I still face in my life.

Where mental health was discussed, there was variation as to the level of detail and how the topic was approached. As such, the phrase ‘box ticking’ was used by several participants to describe what was primarily felt to be a bureaucratic procedure with little relevance to individual need.

Stephen: But it’s all protocol isn’t it; it’s all written in front of them. They’re asking you set questions where it’s irrelevant to what is actually up with you.

During the interviews, multiple participants described past experiences of abuse, bereavement and difficult social circumstances that had contributed to them becoming unwell. In some instances, participants felt obligated to disclose these difficult or traumatic life events in their face to face assessment to provide proof of illness.

Callum: [The assessor said] “If you don’t answer this question, then your money could be stopped” and it felt like I were being held to ransom. Things that I didn’t want to tell them they were making me tell them and it’s like, well I don’t want to tell you about these things it’s personal. You know and a lot of it is already down in my medical history, and I’ve had two medicals prior to this last one.

In an eligibility assessment setting, where the assessor was unknown to the claimant and where financial support was dependent on the disclosure of information, providing proof of illness in this way was distressing. Few individuals in the sample had access to a specialist mental health service to provide written evidence.

Jenny: I weren’t there for long, she walked out, got a second opinion, said “right, you can go”. I couldn’t hold a conversation because the questions she were asking me kept making a lump in my throat. I couldn’t speak ‘cos they were too upsetting…so I just broke down.

Participants spoke of the precariousness of relying on social security as a source of income, grounded in a perception that financial support could be withdrawn at any time on an arbitrary basis or by a redefining of eligibility. This perception began at the eligibility assessment stage but continued after financial support was in place.

Sarah: They can push me; am I going to sit here and say have I never contemplated suicide? I think if I wasn’t a person who was frightened to death of dying. There’s many out there who are killing themselves to this day because they’re having their benefits took from under their feet constantly, because they’re told that they’re alright and they can go out to work.

As invisible health conditions which were not felt to be fully recognised in the eligibility assessment process, mental illnesses were viewed as adding extra insecurity to being able to maintain receipt of social security payments.

Ruby: [discussing an acquaintance] He’d lost his leg and they failed him on his medical and told him he were fit to go to work. I’m sat there with mental health issues thinking, hang on a minute, there’s people losing their benefits all over with severe disabilities, do I deserve this money?

Alan: It makes me feel vulnerable that they’re going to change things and withdraw support for people. Very vulnerable and secondly, it just makes you feel stigmatised because people can’t see your disability. Obviously when I’m well, I’m able to walk around and do things but literally when I’m not well, I couldn’t even make a cup of tea, I might as well be paralysed.

Support

Where participants had approached organisations for support to assist with the completion of their paper application or to address queries associated with the face to face assessment, experiences were overwhelmingly positive. This included support from job centres, assessment providers and external organisations: for example, Citizens Advice.

Robert: I didn’t know how to fill a benefit form in or anything and they went through every single thing in detail which was really nice. They reassured me that because I’m not working now, I don’t have to pay for my rent, council tax and something else which I was a bit concerned about. They were really nice and helpful.

In our sample, five out of seven of those whose claim ended in payment either had a worker attending the face to face assessment with them or presented supporting evidence from a healthcare service. Advance written or telephone evidence had the benefit of ensuring a smoother and shorter face to face assessment for some of the participants who had access to it. This was helpful in mitigating against a perceived lack of knowledge about mental health on the part of the assessors.

Susan: [The assessment] was more on the medical side of things and they couldn’t see inside my head, so they didn’t understand but luckily the evidence is there on paper.

Workers acted as advocates and assisted with managing anxieties around the claims process. Jenny, for example, missed her first PIP assessment due to a serious self-harm attempt requiring hospital admission and her support workers intervened:

Jenny: Whatever they did, I didn’t have to go for a face to face assessment and I just got a phone call saying that I’d passed it.

Other participants discussed how support staff had telephoned ahead to make sure assessors were aware of the anxieties the person was experiencing, assisted with evidence gathering and even provided food parcels whilst they were awaiting the outcome of their claim. It was not clear from our findings as to the specific role played by workers during face to face assessments, but it is feasible that the addition of support placed less pressure on the individual to self-advocate in what was for many a novel and sometimes intimidating process. Where support was not in place, several participants missed appointments as a result of their mental health problems, leading to financial consequences.

Ruby: Unfortunately, they’d sent me a letter at some point during this time that I’m seriously not very well, my family were looking after the children and I were just constantly in my bedroom. I’d received a letter and at that point I couldn’t open the mail, I were just so low. Then I went to the bank and my money wasn’t there. They’d stopped my money because I hadn’t gone to a medical which I didn’t know I had because of the situation that I were in. They stopped all my money and I went all over Christmas, the full Christmas that year with nothing, no money.

David, for example, described being caught in a seemingly endless cycle of attending WCAs and being found fit for work, then being unable to keep up with work search requirements or attend his appointments consistently due to his mental health, and receiving a sanction. After this, his mental health would deteriorate further, he would be signed off by his GP and begin a new claim for ESA. David reported this process had been ongoing for several years at the time of our assessment and, without any support in place, he felt it was likely to continue indefinitely.

In some cases, it was healthcare workers who advised participants of their eligibility. Alan, for example, had been made aware of DLA and PIP by his GP who then supported his applications. Callum was encouraged by his drug and alcohol service support worker to reapply for ESA because of a deterioration in his health whilst claiming JSA:

‘I were in and out of hospital, I’d cut my wrists, I were taking overdoses and it wasn’t until [support worker] said “no, this is wrong, you should be on the sick. You shouldn’t be having to go to the job centre and sign on”.’

The involvement of healthcare professionals in providing supporting evidence sometimes also created tension. Callum, for example, reported that he had not received support from his GP in relation to fit notes during his period of deteriorating health and this was a clear source of resentment. Thomas had been found ‘fit for work’ and, in disagreeing with this decision, felt that his doctor should be advocating on his behalf. He reported that this had led to repeated appointments to discuss the issue and was, at the time of interview, hoping to be able to obtain fit notes as an alternative course of action.

Discussion

Overall in this sample, experiences of accessing health-related income benefits were mixed. For some participants, the process of assessment through to receipt and maintenance of financial support ran smoothly. A key factor here appeared to be the input of professionals, who submitted additional evidence for claims and attended assessments to provide support. Eleven out of eighteen participants did, however, encounter difficulty during the process and most disagreed with the outcome of their eligibility assessment. Whilst it was not possible from the study to determine baseline level of functioning, that multiple decisions were later overturned on appeal suggests initial outcomes were not always accurate. Nationally, around two thirds of initial ESA ‘fit for work’ decisions are overturned on appeal, albeit small numbers of claimants proceed through to this final stage of challenging the initial outcome (DWP, 2019a).

Eligibility assessments are designed to act as a standalone method of determining financial entitlement. This means that even where no additional information about a person or their health condition is available, level of functioning can still be classified in the assessment itself using an objective, points-based scoring system. Theoretically, this should work well for people with mental illnesses, since only a comparatively small number are in regular contact with secondary mental health services and therefore have access to supporting evidence from a specialist healthcare professional. In reality, participants in our sample felt that their needs were often not appropriately assessed. Key issues included limited opportunity to discuss the impact of mental ill health on functioning and being asked to recount difficult or traumatic experiences. In addition, assessments were felt to focus almost entirely on physical health.

Regardless of whether the claims process was uneventful and the outcome viewed as favourable, eligibility assessments were consistently a source of stress for participants in the sample, in some cases leading to suicidal thoughts. These findings are supported by Barr et al. (Reference Barr, Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Stuckler, Loopstra, Reeves and Whitehead2015b) who attributed an excess of 590 suicides, 279,000 cases of self-reported mental health problems and 725,000 anti-depressant prescriptions to the re-assessment of benefit claims between 2010 and 2013. This does not include the more recent transition from Disability Living Allowance to Personal Independence Payments.

Ultimately, all participants in the sample did receive some form of financial support but the lived experience of social security was for most permeated by fear, insecurity and disempowerment; grounded in a perception that financial support could be withdrawn at any time on an arbitrary basis or by a redefining of eligibility that did not include mental health conditions. Not all claimants in the sample had a negative experience of the claims process, and respondents were especially positive about their experiences of accessing support, which assisted in reducing some of the pressures around navigating the system.

‘Failing a substantial minority’

It is worth noting that evidence from claimants responding to the Work and Pensions Committee (2018), Ipsos Mori (2018) and the Claimant Service and Experience Survey (DWP, 2019b) suggests that more people are satisfied with their experiences of eligibility assessments and the claims process than are not, although these findings are not always disaggregated by health condition. Nevertheless, the claimants who do experience difficulties form a ‘substantial minority’ for whom improvements are needed (Work and Pensions Committee, 2018, p.5). Our research raises concerns about the appropriateness of a system designed to assess current functional abilities that has potential to increase stress and anxiety, requires support to be accessible and that may involve discussion of traumatic historical events. Whilst these factors could impact on all claimants, those with mental health conditions may be particularly affected because of the potential to exacerbate existing psychological difficulties and the low likelihood of having access to specialist supporting information. The potential for differential outcomes by health condition was recognised in the first independent review of the PIP assessment, conducted by Gray (Reference Gray2014). A key recommendation was the implementation of:

“…A rigorous evaluation strategy that will enable regular assessments of the fairness and consistency of award outcomes should be put in place, with priority given to the effectiveness of the assessment for people with a mental health condition or learning disability.” (p4)

In response to this recommendation, a longitudinal survey and interview study was commissioned by DWP to provide an in-depth view of claimant experiences (DWP, 2018a) but although this research forms a key tenet of the evaluation strategy, for statistical reasons the report does not separate responses by health condition (DWP, 2018b). It remains unclear, therefore, as to whether there are differences in levels of satisfaction with the PIP assessment process for people with mental health conditions.

Assessing functional ability

The focusing of assessments on physical rather than mental health was common not only to our research but also to the claimant experiences described in several other reports (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Jones, McNeill, Scullion and Stewart2018; Ipsos Mori, 2018; Money and Mental Health policy institute, 2019). Although the written and face to face WCA and PIP eligibility assessments are designed to assess both physical and mental health-related functionality, it is clear that this is not the experience of some claimants. This is of concern, not only because of the potential direct consequences of denying eligible claimants access to social security entitlements, but because it may also undermine confidence in the process itself, leading to under claiming. Certainly, some people with mental health conditions have seen their payments reduced following recent reforms (Mind, 2016; Full Fact, Reference Fact2017) and an attempt by the Government to remove eligibility for enhanced-rate PIP mobility payments, where the reason given by the claimant was related to psychological distress rather than physical difficulties, was dismissed in the high court as ‘blatantly discriminatory’ (Public Law Project, 2017).

There is a common misconception amongst claimants that assessments will focus on symptoms of illness and be conducted by healthcare professionals with experience of their particular health condition (Gray, Reference Gray2014; Ipsos Mori, 2018) but whilst assessors are registered professionals such as nurses, physiotherapists or occupational therapists, they are not necessarily specialised in the health condition under assessment. This is in keeping with a functional focus: for example, ATOS (2017) have previously noted that “Our role is not to diagnose or treat so specialist knowledge of, for example, mental health diagnosis and treatment is not necessary to be able to understand how an individual’s life is affected” (p23). It has been recommended that the functional basis of the assessment should be clearly communicated to claimants from the beginning (Gray, Reference Gray2014) and that the opportunity should be provided to see questions and be able to prepare responses in advance of the face to face assessment (Money and Mental Health, 2019). Recommendations to improve communications with claimants have been accepted by DWP (2017), which may help to reduce misconceptions and manage expectations about the eligibility assessment process. There are no plans currently to provide advance access to face to face assessment questions, but this could have the benefit of reducing some of the anxieties associated with the process.

Key to building trust in functional assessments, however, is the effective assessment of functioning as it relates to mental health conditions. A particularly contentious component of eligibility assessments is the use of ‘informal observation’ to make judgements about mental state and it has been recommended that the use of such tools should be made clear to claimants (Gray, Reference Gray2014). The assessment of ‘appearance and behaviour’ does feature in clinically recognised tools such as the Mental State Examination (MSE) (Huline-Dickens, Reference Huline-Dickens2013; Soltan and Girguis, Reference Soltan and Girguis2017) but the MSE is designed to provide a snapshot of current mental state in the context of a more in-depth holistic mental health assessment (Soltan and Girguis, Reference Soltan and Girguis2017). Our research suggested that being perceived by the assessor as well-dressed and able to make eye contact were taken as an indicator of being mentally well and the assessment score reduced accordingly. Relying on this type of measure does not take account of the fluctuating nature of some mental health conditions which only a more detailed assessment could reveal and is potentially unreliable given that, in the assessment set up, claimants may feel the need to present in a formal manner to be taken seriously.

Most participants in our sample reported difficult life events that had precipitated their mental health condition and were in some cases ongoing. Face to face assessments are not expressly designed to ask about past or sensitive topic areas but, where there is a lack of supporting information available, disclosures of this type may be perceived as necessary by claimants in order to provide an appropriate level of detail. This has the potential to cause distress both during and after the assessment. Similar concerns have been raised about the appropriateness of questions relating to risk of suicide (Work and Pensions Committee, 2018).

Of those surveyed by Ipsos Mori (2018) who received a financial award, 82% felt the questions asked of them were relevant and appropriate, compared to 42% of those who were not awarded PIP. Potentially then, disagreement with the assessment outcome may influence responses. It is, however, equally feasible that a person is less likely to be awarded PIP if the questions asked during their assessment are irrelevant or inappropriate.

It is not clear as to whether there is appropriate aftercare provision in place for claimants following their assessment and only one of our participants referred to their assessment being stopped because they were distressed, despite several reporting that they were visibly upset at the time. Ensuring that claimants are made explicitly aware that the disclosure of sensitive information relating to their health condition is voluntary and that non-disclosure will not disadvantage the claim is key.

Assessor variation

Whilst standardised in principle, assessments are carried out by individuals and it is possible that this may account for some of the differences in claimant experiences. Certainly our findings were mixed: some participants found their assessor to be empathetic and supportive, whilst others felt there was an underlying assumption their claim was fraudulent and accordingly felt negatively judged. Similar variation was also found in focus groups conducted during the first Gray review (Reference Gray2014).

In their survey of PIP claimants, Ipsos Mori (2018) reported that 69% of respondents felt the questions they were asked during their assessment enabled them to fully explain how their health condition impacted on functioning, whilst 89% felt they had been treated with dignity and respect by their assessor. In contrast, of respondents surveyed by the charity Money and Mental Health (2019), only 23% felt they had opportunity to explain how their health condition affected them during the assessment, 18% felt the assessor understood the impact of their mental health problems on functioning and 40% felt that they were listened to carefully during their assessment. While there are differences in the samples, Money and Mental Health (2019) surveyed claimants undergoing eligibility assessments for a range of benefits all of whom reported having a mental health condition, whilst Ipsos Mori (2018) spoke with a broader sample of PIP claimants; it is plausible that the large differences in satisfaction between the samples are driven by the more negative experiences of claimants with mental health problems.

The variation in experiences of assessors is in itself problematic, particularly in a context where aftercare or support may not be as readily accessible as in other mental health assessment settings. Gray (Reference Gray2014) notes that:

“The face-to-face assessment has been designed for consistent application by any health professional, wherever they are in the country. Different health professionals will have different personal styles but this should not result in any material difference in the quality of the assessment.” (p63)

Variation in assessment styles is to some extent inevitable but this is of concern where the outcome is a poorer assessment that does not accurately and sensitively approach the topic of mental health. In one survey, for example, 85% of claimants with a mental health condition reported that their mental health had deteriorated following a face to face eligibility assessment (Money and Mental Health, 2019). The use of video recording for PIP assessments is currently being trialled by DWP (Rudd, Reference Rudd2019) and this may assist with improving the quality of interviews, alongside providing evidence where there is a disagreement between claimant and assessor on the correct assessment outcome. It should also be noted that whilst assessors provide information about the claimant, it is ‘decision makers’ within DWP who ultimately decide whether or not the person is eligible for a financial award. Clarity around the training and support offered to decision makers within DWP would also be welcomed.

The role of support

Support included assistance with the completion of paper forms and attending the face to face assessment. Family, friends and professionals all contributed in this way and, in our sample, most of those who received support were awarded payments. Similarly, Ipsos Mori (2018) found that those who had taken someone with them to their face to face assessment were more likely to be awarded PIP than those who had not (70% compared to 62%). Claimants in both our study and other reports (Gray, Reference Gray2014; Ipsos Mori, 2018) who contacted DWP or their Assessment Provider were largely positive about the support they received in relation to assistance with completing the paper application and in arranging the practical aspects of face to face assessments.

Although arguably some people with long term health conditions will always require support to navigate the social security system, an assessment process in which claimants who access support have a greater chance of success is arguably not working entirely effectively or equitably. Not all claimants will have access to support from family or health professionals to provide written evidence or to attend the face to face assessment and so further evidence is needed to assess whether there is a definitive difference in outcomes for claimants who did and did not receive support during the assessment process.

In our study, at least part of the role of those supporting claimants appeared to consist of mitigating against some of the negative mental health effects caused by the eligibility assessment itself. Our findings also demonstrate that involving healthcare professionals in the eligibility assessment process has the potential to impact on therapeutic relationships: where, for example, there is tension or disagreement in relation to eligibility assessments and their outcomes. In addition to the distress caused by the assessment process itself, this raises questions as to whether the current process is placing unnecessary demand on healthcare and other statutory services.

Limitations

Our study was undertaken in one city in England; therefore it is possible that the findings relate to issues associated with a particular assessment centre. This is not the case for the other evidence discussed here, however, which comes from claimants across the UK. Instead, our research arguably contributes to identifying that there may be ‘shared typical’ experiences which are suggestive of being associated with the underlying policy context, rather than with specific individuals or assessment settings (McIntosh and Wright, Reference McIntosh and Wright2019).

The participants in our research self-reported their mental health condition and it was not feasible to obtain an independent assessment following the criteria for the WCA or PIP assessment, so it is not possible to determine whether assessment outcomes were an accurate reflection of level of functioning. In addition, the sample consisted of individuals accessing community support organisations and so findings may be different for those who are not engaged in this type of service.

Aside from the study undertaken by Pybus et al. (Reference Pybus, Pickett, Prady, Lloyd and Wilkinson2019) there is limited research more broadly as to whether there are actual differences in claim outcomes for people with mental health conditions and, if so, the magnitude of the difference between the experiences of people with mental health conditions and other claimant groups. Certainly, charities and support organisations have raised concerns about the appropriateness of assessment questions for claimants with other health conditions and disabilities and about the distress caused by the claims process (Work and Pensions Committee, 2018).

Conclusions

In the time since our research was carried out, DWP have accepted a number of recommendations from the Gray review (Reference Gray2017) relating to PIP assessments. These include clearer communication with claimants; greater checks on consistency across assessments; the use of Mental Health Champions by assessment providers and updated guidance on the assessment of fluctuating health conditions (DWP, 2017). Yet, whilst improvements are in progress, the evidence discussed here suggests that, even if successfully implemented, these do not go far enough.

Where an individual has undergone a full and holistic assessment by a psychiatrist, community mental health professional or social care professional in the preceding six months, the obligation to attend a face to face assessment should be removed. If this information is not available, then any claimant with a primary mental health condition should have access to a functional assessment completed by a mental health professional. Regular auditing of face to face assessments that focus on whether mental health has been discussed holistically and in addition to the completion of an MSE is also key to ensuring a thorough assessment of difficulties.

Mental health support should be offered proactively and as standard to all claimants undergoing a face to face eligibility assessment, including the provision of appropriate aftercare. To monitor and improve the service, evaluations should analyse claimant experiences by different health conditions. With plans to introduce a single assessment covering multiple income benefits, it is more important than ever that the process works effectively for all claimants. Given the potential for harm described here, it would be prudent to consider removing the requirement for claimants with health conditions and disabilities to attend face to face assessments altogether.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number: 1652530). The funders had no influence over data collection, analysis, interpretation of results or the writing of this paper. All views represented here are those of the authors.

Declaration of interest

None.