Introduction

The World Health Organization identifies smoking as the leading cause of preventable death internationally, with 4.9 million deaths per year (World Health Organization 2003). In 2012, the amount of healthcare expenditure due to smoking-attributable diseases totalled 5.7% of global health expenditure (Goodchild, Nargis, & Tursan d'Espaignet, Reference Goodchild, Nargis and Tursan d'Espaignet2016). Worldwide, more than one billion people smoke tobacco, or identify as smokers (World Health Organization 2017). While this number is decreasing year-by-year, smoking-related illness remains a large proponent of respiratory and cardiac disease. Tobacco control should be at the forefront of every future nationwide healthcare policy. To this end, a 2012 Cochrane review, by Rigotti et al., demonstrated the effectiveness of brief smoking cessation interventions, on patients, when given by a healthcare professional (Rigotti, Clair, Munafo, & Stead, Reference Rigotti, Clair, Munafo and Stead2012; Smith, Reilly, & Houston Miller, Reference Smith, Reilly, Houston Miller, DeBusk and Taylor2002). Hospitalised patients, in particular, are more receptive to intervention than the general population, especially those who have been admitted with tobacco-related disease (McBride, Emmons, & Lipkus, Reference McBride, Emmons and Lipkus2003). The inpatient hospital setting provides an optimal time for intervention, as healthcare workers are clearly able to identify patients who smoke tobacco (Raupach et al., Reference Raupach, Falk, Vangeli, Schiekirka, Rustler and Grassi2012). The inpatient setting provides other inherent incentives, such as increased patient motivation to quit, resources to manage withdrawal symptoms on-site and an ideal ability to facilitate follow-up with primary care for patients following smoking cessation interventions. Furthermore, it has its own unique features, separate to provider advice in other settings that are relevant to intervention, such as the short window of opportunity to intervene and oftentimes a lack of an established relationship with the patient. As such, the inpatient setting provides a unique opportunity to provide cessation support, to avoid readmission and to reduce related mortality (Lawson & Flocke, Reference Lawson and Flocke2009; Mohiuddin, Mooss, & Hunter, Reference Mohiuddin, Mooss, Hunter, Grollmes and Hilleman2007).

However, despite its proven effectiveness, various research studies have revealed low levels of cessation intervention being carried out by healthcare professionals in the inpatient setting (Berlin, Reference Berlin2008; Katz et al., Reference Katz, Weg, Fu, Prochazka, Grant and Buchanan2009; Svavarsdóttir & Hallgriḿsdóttir, Reference Svavarsdóttir and Hallgriḿsdóttir2008). While different studies attribute this lack of engagement with provision of cessation advice to a variety of factors, no study has yet systematically reviewed these barriers or placed these determinants within the context of behaviour change theory.

We therefore aimed to systematically review studies which explore the barriers to implementation of smoking cessation interventions in a hospital inpatient setting. To provide further insight into these barriers, we report how often such barriers are reported, and we group the findings according to the COM-B model of behaviour; reflecting ‘Capability’, ‘Motivation’ and ‘Opportunity’ (Michie, van Stralen, & West, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). This approach allows for more in-depth exploration of the barriers to provision of smoking cessation interventions for hospital inpatients.

Methods

Protocol and registration: The systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (Protocol number: 42016042499). No protocol was published.

Eligibility Criteria: No restrictions were placed on study type. Any published research articles that reported barriers to the provision of smoking cessation advice in hospital settings were included. The inclusion criteria were studies based in the hospital inpatient setting, which detailed barriers to smoking cessation interventions and which were in English. Studies not in English, based outside of the hospital setting or unavailable as a full-text document were excluded.

Information sources: On the 4th of January 2017, an initial search strategy was developed using the databases OVID MEDLINE, OVID PsycINFO and Cinahl; three online databases. Google Scholar was used to find articles citing the included studies.

Search: Key words such as ‘physician role’, ‘counselling’, ‘intervention’, ‘smoking cessation’, ‘tobacco use cessation’, ‘barriers’ and ‘factors’ were used in the search strategy. Each of these search terms was entered into the search feature of OVID MEDLINE, OVID PsycINFO and Cinahl. For example, using OVID MEDLINE's search engine, ‘physician role’ OR ‘counselling’ OR ‘intervention’ was searched. Then ‘barriers’ OR ‘factors’ was searched. Last, ‘smoking cessation’ OR ‘tobacco use cessation’ was searched. To complete our search of this database, the limits from the three searches were entered into the search engine, using the qualifier ‘AND’. Following this, the results of this final search were transferred to Endnote, where they were compiled with the search results from the other two search engines. Any studies that featured the key terms and were available up to the 4th of January 2017 were included. The final search involved hand searching the references and citing articles of the included studies.

Study selection: Studies were identified and compiled in an Endnote library. Duplicates were removed. Next, any research articles which did not meet the eligibility criteria according to title were detected and removed. These included papers not in the English language or those based outside of the hospital setting. After this, each of the abstracts was evaluated for relevance to the research topic.

Data collection process: A full-text copy of each research study was located. Two authors independently reviewed the articles and extracted the information. Any disagreements were discussed.

Data items: Any item which was reported as a barrier was recorded.

Risk of bias, summary measures, synthesis and additional analyses were not applicable to the present review.

Results

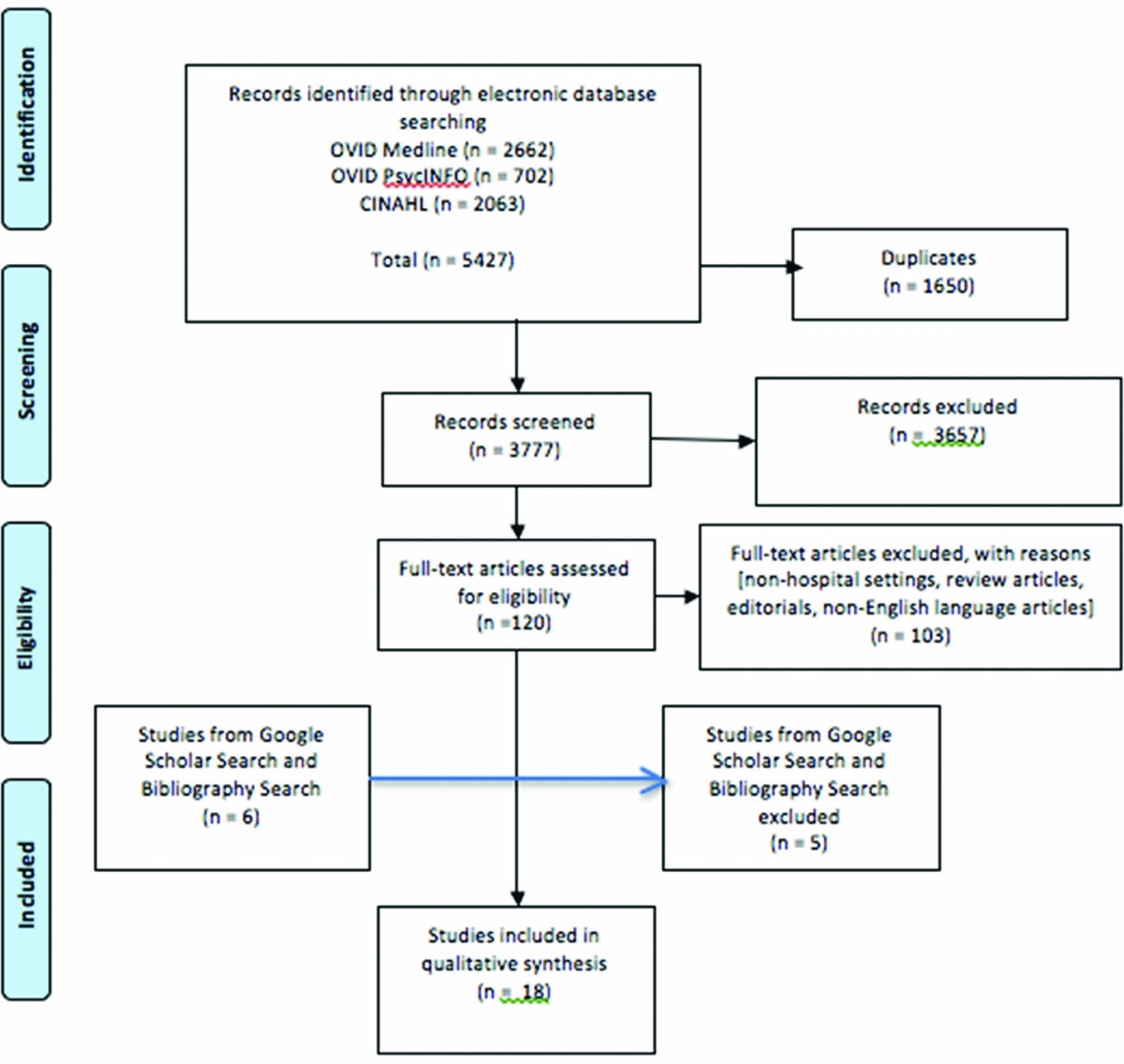

Figure 1 is the study flowchart. The review yielded 18 research papers for final inclusion.

Figure 1 Barriers to smoking cessation interventions systematic review – PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1 lists an overview of the 18 studies. The studies were carried out between 2001 and 2016 included hospitals in the US, Canada, England, Australia, Taiwan, Germany, Iceland, Scotland, China and the UAE. Eleven of the studies concerned nurses, while four studies specifically interviewed physicians. One study consisted of data from midwives and two studies assessed assorted healthcare professionals in the inpatient setting. Methodologies used ranged from self-completed questionnaires on healthcare worker practices to semi-structured interviews. Twelve studies were quantitative with six qualitative studies.

Table 1 Overview of studies

Table 2 details the 20 barriers found, under the headings of Capability, Opportunity and Motivation, including the number (%) of studies that identify each barrier.

Table 2 Smoking cessation intervention barriers, using the COM-B behaviour change model

The most common barrier were lack of time (78% of studies), lack of knowledge (regarding smoking cessation interventions; 56%), perceived lack of motivation to quit (44%) and lack of support (including from other colleagues, the hospital and the wider healthcare system; 44%). Barriers reported reflected all three dimensions of the COM-B model. Seven barriers were reported by less than 20% of the studies.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to collate the healthcare professional reported barriers to the provision of smoking cessation advice in inpatient settings. Twenty barriers to smoking cessation interventions were identified in the 18 studies that were found, which reflected each dimension of the COM-B Model. The most commonly cited barriers were lack of time, knowledge, support and a perceived lack of patient motivation to quit. The findings are discussed subsequently as per the COM-B model.

Capability

In the area of capability, most studies reported that clinicians lacked knowledge, skills and training to deliver smoking cessation advice. The most cited barrier was ‘Lack of knowledge’, cited in 56% of studies. The second most cited was a ‘Need for additional training’, cited in 39% of studies. Indeed, the finding that these attitudes were significantly less likely to provide cessation advice has repeatedly been shown in previous literature (Forman, Harris, Lorencatto, McEwen, & Duaso, Reference Forman, Harris, Lorencatto, McEwen and Duaso2017; Preechawong, Vathesathogkit, & Suwanratsamee, Reference Preechawong, Vathesathogkit and Suwanratsamee2011; Siddiqi, Dogar, & Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi, Dogar and Siddiqi2013). These findings highlight a clear need for enhancing clinicians’ self-efficacy to deliver such advice. Over a quarter of the publications reviewed acknowledge the problem of a ‘lack of skills’ on the part of clinical practitioners to effectively promote smoking cessation interventions. This failing in communicative techniques is also evidenced by prior research on the subject, most notably in a 2013 Cochrane review by Carson et al., which shows that physicians who are trained in cessation delivery are more likely to use these skills and that their patients are more likely to quit smoking successfully (Berland, Whyte, & Maxwell, Reference Berland, Whyte and Maxwell1995; Carson et al., Reference Carson, Verbiest, Crone, Brinn, Esterman and Assendelft2012).

Interestingly, two separate publications in this review, acknowledged the negative impact that hospital facilities themselves can have on intervention effectiveness, encapsulated by the ‘absence of smoke-free hospital campus’ in the inpatient setting. This concept is supported by previous research regarding patients’ smoking in a smoke-free hospital and this particular finding highlights the necessity of making the inpatient setting a tobacco-free zone (Rigotti et al., Reference Rigotti, Arnsten, McKool, Wood-Reid, Pasternak and Singer2000). Overall, these findings not only match the capability dimension of COM-B, they also provide important evidence that these are subsumed within the policy context of the Behaviour Change Wheel, and that interventions to address these barriers will be rooted within an overall hospital or health services policy.

Opportunity

Most studies identified that a lack of time, support or resources were barriers to smoking cessation interventions. The most cited barrier was ‘Lack of time’, cited in 78% of studies, which was also the most cited barrier overall. The second most cited was a ‘Lack of support’, cited in 44% of studies. This perceived absence of adequate intervention support from colleagues hospital administration or from primary care physicians, could be seen as a policy issue, to be addressed. Perceived lack of professional support contributing to an inability to deliver smoking cessation interventions has been identified in previous research and eight different papers here support this view (Lala, Csikar, Douglas, & Muarry, Reference Lala, Csikar, Douglas and Muarry2017). The issue of time constraints being a leading obstacle to smoking cessation interventions has been well explored in previous literature and is supported by our findings here (Brotons et al., Reference Brotons, Bjorkelund, Bulc, Ciurana, Godycki-Cwirko and Jurgova2005; Twardella & Brenner, Reference Twardella and Brenner2005). However, this review specifically highlights healthcare workers’ difficulty with not possessing a clear hospital-directed mandate to intervene in smoking cessation. A heavy or overwhelming workload has been previously described by similar research (Carson et al., Reference Carson, Verbiest, Crone, Brinn, Esterman and Assendelft2012). The managerial issue of sparse resources for smoking cessation interventions was identified in over a third of the publications reviewed. This widespread recognition was expected, given the number of previous publications that have referenced the issue (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Richter, Sorensen, Hoerger, Hicks and Engelgau2002; Kanodra et al., Reference Kanodra, Pope, Halbert, Silvestri, Rice and Tanner2016; Sarna et al., Reference Sarna, Bialous, Wells, Kotlerman, Wewers and Froelicher2009).

It could be argued that a ‘lack of support’, ‘lack of resources’ and ‘absence of mandate to intervene’ are barriers which are similar enough to be grouped as one heading, such as a ‘lack of structural support’, but given how frequently each barrier was specifically referenced throughout the studies in the review, it was decided to cite each barrier individually, to provide maximum clarity for healthcare professionals. Similarly, we decided that the barrier of a ‘heavy or overwhelming workload’ was conceptually different from a ‘lack of time’, as the three papers, which referenced this barrier, cited it as a separate issue from the large workload. This allows us to highlight both of these issues as unique factors which need to be ameliorated to provide the best possible care in the inpatient setting.

Motivation

In the COM-B model category of motivation, the most cited barrier was a clinician-expressed belief in a ‘Lack of patient motivation’, cited in 44% of studies. This had been identified by various publications as a substantial factor to poor provision of smoking cessation interventions and so, it is unsurprising that it was reported in the papers reviewed (Cabana et al., Reference Cabana, Rand, Powe, Wu, Wilson and Abboud1999; McLeod, Somasundaram, Howden-Chapman, & Dowell, Reference McLeod, Somasundaram, Howden-Chapman and Dowell2000; Mohiuddin et al., Reference Mohiuddin, Mooss, Hunter, Grollmes and Hilleman2007; Sarna et al., Reference Sarna, Bialous, Wells, Kotlerman, Wewers and Froelicher2009). This perception stands in sharp contrast to patient reports and behaviour; in numerous studies, a majority of patients (typically around 70%) want to quit and most are willing to make a quit attempt. Consistent with this, cessation interventions that use proactive recruitment at the population level typically enrol a large percentage of eligible smokers (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Van Ryn, Sherman, Burgess, Noorbaloochi and Clothier2014; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Ulbricht, Baumeister, Schumann, Ruge and Bischof2008; Tzelepis et al., Reference Tzelepis, Paul, Wiggers, Walsh, Knight and Duncan2011). The second most cited barrier was a ‘Lack of confidence’, cited in 38% of studies. This lack of clinical confidence in addressing patient's smoking practices is noteworthy as previous research had suggested that healthcare workers were largely confident and willing to raise the topic of smoking cessation with patients (Sarna, Wewers, Brown, Lillington, & Brecht, Reference Sarna, Wewers, Brown, Lillington and Brecht2001; Sarna et al., Reference Sarna, Bialous, Wells, Kotlerman, Wewers and Froelicher2009; Willaing & Ladelund, Reference Willaing and Ladelund2004). Our review indicates that a large portion of healthcare workers still view themselves as lacking confidence in addressing this issue. Personal discomfort on the part of clinicians when broaching the subject of tobacco cessation interventions has been previously identified (Pipe et al., Reference Pipe, Sorensen and Reid2009). One study identified the barrier of smoking being seen as ‘a coping mechanism for patients’ by healthcare workers, which has been similarly described in previous literature (Acquavita, Talks, & Fiser, Reference Acquavita, Talks and Fiser2017). Prior research has demonstrated that providing training to physicians and other healthcare workers substantially boosts their efficacy, which then translates into improved cessation intervention delivery (Carson et al., Reference Carson, Verbiest, Crone, Brinn, Esterman and Assendelft2012). It is possible that such attitudes could be addressed at an earlier stage, with students being trained to provide cessation counselling prior to qualification (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Ward, Mellon, Gunning, Stynes and Hickey2017). This attitude was seen as an altruistic act on the part of the healthcare professional and is interesting to note as it strays from the generally accepted view that all tobacco use, by inpatients, should be ended. These deficits could be ameliorated through implementation of targeted education and training programmes for healthcare providers.

Not viewing smoking cessation intervention as a priority has been previously reported (Rice, Hartmann-Boyce, & Stead, Reference Rice, Hartmann-Boyce and Stead2013) with over a quarter of publications in the present review acknowledging this barrier. This attitude requires examination at a training and educational level to ensure adequate provision is made to aid patients in quitting smoking. The potential barrier of insufficient healthcare worker motivation or interest, which was described by four different publications, also has precedence in previous research (Borrelli et al., Reference Borrelli, Hecht, Papandonatos, Emmons, Tatewosian and Abrams2001; Hall, Vogt, & Marteau, Reference Hall, Vogt and Marteau2005). This belief is heavily linked with the reported belief that healthcare workers require financial reward or career recognition to initiate smoking cessation interventions, which was also identified in four studies in our review, as a ‘lack of incentive’. This attitude runs contrary to the typically altruistic notion of healthcare workers, but it also has been cited in previous literature, especially in the outpatient setting (Brotons et al., Reference Brotons, Bjorkelund, Bulc, Ciurana, Godycki-Cwirko and Jurgova2005; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Van Ryn, Sherman, Burgess, Noorbaloochi and Clothier2014). Our review demonstrates that this perceived insubstantial incentive, for addressing smoking cessation, is equally present in the inpatient environment, albeit this may depend on the healthcare system in which professionals are employed.

Four publications reviewed cited, the scepticism healthcare workers may have regarding smoking cessation intervention effectiveness. This was seen as a tangible obstacle to delivery of interventions and is another attitudinal belief identified by our review, which is congruent with previous research on the subject (Tong, Strouse, Hall, Kovac, & Schroeder, Reference Tong, Strouse, Hall, Kovac and Schroeder2010). It is interesting to note that three of the reviewed studies detailed the negative impact a physician's own smoking history could have on the success of cessation intervention. While healthcare worker tobacco use has been reported before (Pipe, Sorensen, & Reid, Reference Pipe, Sorensen and Reid2009), it is interesting that this personal practice would impact on providing optimal care for patients. A previous research study, in Syria, showed that physicians who smoke were less likely to deliver cessation interventions, support non-smoking policies and believe that smoking was harmful (Asfar, Al-Ali, Ward, Vander Weg, & Maziak, Reference Asfar, Al-Ali, Ward, Vander Weg and Maziak2011). This suggests that to increase the effect this potential barrier has upon future interventions, healthcare workers should be mindful of not permitting their own personal tendencies and habits from negatively affecting patient care.

The one noted instance of ‘social pressure’ being seen as a barrier to a healthcare worker providing smoking cessation intervention is unusual. Although there is precedence for it in the literature, it may be specific to the demographic of male physicians in China, where these studies were carried out (Cheng, Ernster, & He, Reference Cheng, Ernster and He2000; Kohrman, Reference Kohrman2004). Future research should investigate whether this barrier is encountered in other regions.

Finally, three studies expressed the belief that healthcare workers ‘negative past intervention experience’ could impact the success of smoking cessation interventions. This viewpoint has been identified by previous research on the subject (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Van Ryn, Sherman, Burgess, Noorbaloochi and Clothier2014). The fact that such a small portion of our studies reviewed identified this (17%) suggests that it is perhaps not as pressing a failing as some of the more common barriers which are categorised under the banner of motivation. Nevertheless, to achieve the optimum outcomes for smoking cessation interventions, each of the 20 barriers identified by this review must be considered as potential areas for improvement, in the inpatient setting.

An interesting point to note is viewing these various studies in the context of self-efficacy to deliver cessation interventions. Several of the barriers identified in the study detail a failing in healthcare professional efficacy, such as ‘lack of confidence’, ‘lack of healthcare worker interest or motivation’ and ‘lack of incentive’. Negative past experiences likely reflect poor efficacy, due to awareness of one's lack of expertise and/or lack of success in getting patients to quit, which makes the physician reluctant to intervene in the future. For healthcare workers to provide the optimum care for patients, it is crucial that each identifies the personal efficacy areas, in which they can improve, to correctly deliver clear and effective intervention advice.

Implications and limitations

These results are not only useful to practicing healthcare workers, but also for healthcare managers and educators, as they clearly set out the areas of inpatient care that could be addressed through extra training in providing smoking cessation interventions. In contrast to previous research which investigated perceived barriers among physicians (Berlin, Reference Berlin2008) or nurses (Berland et al., Reference Berland, Whyte and Maxwell1995; Svavarsdóttir & Hallgriḿsdóttir, Reference Svavarsdóttir and Hallgriḿsdóttir2008; Twardella & Brenner, Reference Twardella and Brenner2005), this systematic review identifies barriers synonymous with all healthcare workers in the inpatient setting, including doctors, nursing staff, caregivers, midwives and counsellors. However, the limitation inherent in the study design is that by focusing specifically upon the inpatient setting, it is not possible to assess the barriers to providing smoking cessation services in the primary care setting or in community outreach programmes. Notably, similar barriers have been reported in primary care (Vogt et al., Reference Vogt, Hall and Marteau2005). Like all systematic literature reviews, this research is also limited by the quality of the data reviewed. Another limitation is that through utilising the COM-B model, there may be certain barriers that were outside of the scope of this paper. One study, by Goldstein et al., details particular efforts in smoking control in the hospital setting (implementing smoke-free policies in multiple hospitals and identifying smoking cessation programmes available to healthcare employees, but its findings are outside of the framework of the COM-B model and, as such, are unsuitable for inclusion in our results (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Westbrook, Howell and Fischer1992). A further limitation is that the current analysis does not provide any weighting to the studies, or indeed, to study quality. Future work could address these limitations. A strength of the study is the reporting of barriers within a behaviour change framework that will guide future interventions. Implementation of smoking cessation interventions into inpatient settings, accounting for barriers as reported here, should be a priority.

Conclusion

This review highlights the impediments, attitudes and beliefs that can act as barriers to the provision of smoking cessation in the hospital inpatient setting. These perceived barriers range from administrative issues of resource allocation, to clinical practitioners’ ingrained beliefs, to aspects of social and professional discomfort. To address and ameliorate these barriers to the provision of smoking cessation interventions, changes need to be multidisciplinary and across the spectrum of hospital departments. For example, the time constraints that healthcare workers described in the review could be best solved at the managerial level, while patient resistance to treatment is easier to address in the clinical ward setting. Of the variety of options for improving hospital management of tobacco cessation, one suggested solution is the implementation of ‘opt-out’ programmes, which have been explored in several recent research papers (Faseru et al., Reference Faseru, Ellerbeck, Catley, Gajewski, Scheuermann and Shireman2017). This practice involves healthcare professionals providing smoking cessation treatment to every tobacco-smoking patient, regardless of their desire to quit. This practice of offering smoking cessation resources to every applicable inpatient may help to alleviate the burden on the cessation barriers identified in this review and further research studies could investigate this option, while targeting the noted barriers. This systematic review serves to emphasise the need for further education and training of healthcare professionals, in the inpatient setting, to maximise the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions and to minimise the occurrence of tobacco-related disease.

Financial Support

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Research Summer School programme, based in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Conflicts of Interest

There were no conflicts of interest arising from this systematic review.

Ethical Standards

The creation of this systematic review was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set by PROSPERO. (Protocol number: 42016042499).