I INTRODUCTION

Fresh water was a valuable resource in the Roman world, that came from sources both man-made (aqueducts) and naturally occurring (rivers, streams, lakes). Romans used fresh water for a variety of productive activities, such as irrigation and milling.Footnote 1 The Roman state also had interests in fresh water, both financial (e.g. tax revenue derived from agriculture) and ideological (e.g. imperial benefaction in hydraulic construction). Yet, it appears that fresh water was largely unregulated, because emperors issued little legislation on it until the late law codes.Footnote 2 Other types of evidence, however, are available for the early Empire, roughly from Augustus through the Severan jurists (27 b.c.–a.d. 235), including Frontinus' treatise on the aqueducts, municipal laws, and the writings of the Roman jurists in the Digest of Justinian. Even if there was no centralized administration of water, the evidence is sufficient to reconstruct the rights regime in fresh water as well as the policy and working principles that guided it.Footnote 3

Roman discussions of fresh water begin in Republican literature with the assumption that it should be free and open to all.Footnote 4 Cicero listed running water, aqua profluente, first among the common goods that all humans share (Off. 1.52). The phrase, aqua profluens, is neither a common nor an exclusive expression nor is it a legal term.Footnote 5 Aqua viva is similarly restricted, used for ‘spring’ primarily by surveyors when marking boundaries.Footnote 6 Romans recognized fresh water as a diverse resource, most simply defined in contrast with the sea (e.g. Varro, Rust. 3.17.3). More commonly they referred to it by the name of a particular water feature, e.g. amnis, lacus, flumen, rivus.Footnote 7 But fresh water could also have a man-made source, such as an aqueduct. The usage of rivus and lacus reflects the intersection of natural and man-made, as does the Romans' hydraulic infrastructure: aqueducts were fed by springs, springs were regularly improved, and rivers were often dammed to facilitate diversions.Footnote 8 Likewise both natural and man-made sources of fresh water were endowed with ideological meaning through military conquest and imperial government.Footnote 9 Despite the lack of a single term or definition, the Romans saw in fresh water a resource to be regulated and organized for the benefit of individuals and the state.

The earliest evidence for law on fresh water concerns its removal rather than supply. The actio aquae pluviae arcendae protected landowners from damaging run-off already in the Twelve Tables (c. 450 b.c.). The Twelve Tables also dealt with the supply of fresh water through the servitude for aquaeductus, a type of property right in water.Footnote 10 But there was much diversity in the legal treatment of fresh water. First, it could be governed by both property and personal (or contractual) rights. In this respect, aqueducts were distinguished from natural sources, since water from the aqueducts was typically governed by personal rights while water from natural sources was treated as property. But the distinction between personal and property rights was not systematized until the Severan era.Footnote 11 Within property law itself, the treatment of fresh water is even more complicated because it was assigned to different categories that were neither clearly defined nor mutually exclusive. Roman property categories began from the distinction between things subject to human law and those subject to divine law.Footnote 12 Within human law, property could be either private (res privata) or public (res publica) or no-one's property (res nullius).Footnote 13 Fresh water could and did fall under all these categories in Roman law. For example, a spring on land owned by an individual was considered private property whereas a stream on ager publicus was public property.Footnote 14

Property categories were important in defining rights to fresh water because they affected the legal remedies available to protect those rights. Sacred springs, for example, were for the most part governed by religious law because they were classified as sacred property, res divini iuris, in contrast to property subject to human law, res humani iuris.Footnote 15 For res humani iuris, there were separate remedies for public and private property. For example, disputes about fresh water sources were resolved through vindicatio only when private property was at stake. And decisions about when to apply the praetorian interdicts depended on property categories because some interdicts protected only public property, others only private property.Footnote 16 An interdict was a legal remedy implemented by the praetor that protected an individual's interest in property. Several interdicts applied to fresh water, and there is extensive juristic commentary on them. Yet there was no universal definition of public fresh water, although the jurists agreed about public rivers, that they had to flow year round.Footnote 17 While ‘public’ might seem to be a self-evident concept, Romans — especially the jurists — debated its meaning and scope.Footnote 18

In the legal sources, public water generally was characterized by the notion of shared use, an idea formulated by Ulpian as usus publicus. Footnote 19 The same notion informs the category of res communes, as defined by Marcian: ‘air, running water, the sea and with it the sea shore, these things are in fact common to all by a sort of natural right’, ‘et quidem naturali iure omnium communia sunt illa: aer, aqua profluens, et mare, et per hoc litora maris' (D. 1.8.2.1 Marcian. 3 Inst.). Marcian's expression recalls Cicero and his philosophical approach, and it also evokes public property which was also to be shared by all, although it is not clear whether Marcian meant to assimilate the categories.Footnote 20 For fresh water, shared use is most often associated with public rivers, which the jurists describe as open-access, to borrow a modern term.Footnote 21 Yet the jurists invoked shared interests in fresh water most often when they discussed regulating it (i.e. when it was not treated as something to be shared freely), for example, in applying the interdicts to restrict use of a public river. Throughout the period of Classical Roman law, public property had a dual nature — open-access and regulated — and perhaps for this reason public property generated a good deal of discussion among the jurists, most of it focused on defining the categories. The jurists' focus on categories may result from the importance of the interdicts in regulating fresh water or efforts to accommodate the ius civile to property regimes in the provinces before a.d. 212. Or it may reflect their academic debates about abstract legal notions or the effects of compilation. Scholars have mostly followed the jurists in examining the definitions of property categories and the views of individual jurists, without finding much systematization.Footnote 22

The focus on property categories generally and on public property in particular has proved inadequate to understanding the regime of water rights in Roman law. The problem is particularly clear in the treatment of public rivers. Since the category of res publicae is defined as free and open to all, public rivers should be open-access. Yet the jurists recognized regulation through the praetorian interdicts as well as imperial rescripts and senate decrees. While some primarily older scholarship attempted to resolve the inconsistency one way or another, the current consensus view endorses the disjunction.Footnote 23 This paper offers a broader rationale of rights in public water that transcends property categories, bridging legal and historical scholarship on water rights. Historians tend to discuss civic aqueducts as a feature of imperial administration, using inscriptions and Frontinus primarily.Footnote 24 Legal scholars focus on legal concepts treated in the imperial codes and the Digest of Justinian.Footnote 25 Some studies address both kinds of evidence, but none offers a co-ordinated examination of both public and private water rights.Footnote 26 This paper takes a new approach to property law that both moves beyond property categories and combines different types of evidence to uncover continuities in the treatment of various types of fresh water.

II A NEW APPROACH TO ROMAN WATER RIGHTS

The new approach here applied to Roman water rights treats rights as a ‘bundle’, a concept drawn from legal scholarship on property rights, specifically ownership. Roman economic and legal historians have recognized that property law was a critical tool in the Romans' exploitation of other natural resources, and that ownership in Roman law was not monolithic.Footnote 27 Ownership was described by Honoré in a well-known article as a ‘bundle of sticks’ or component rights, such as residual rights or a right to alienate.Footnote 28 More recently, scholarship on contemporary environmental law has adapted the bundle approach to environmental resources. This ‘environmental bundle’ typically includes rights of access, withdrawal, management, exclusion and alienation.Footnote 29 A person with a right of exclusion can bar others from entering into (access) or taking from (withdrawal) the resource. For example, on a river, a right of access might mean travel by boat on the water whereas withdrawal could involve diverting the water into a field for irrigation.Footnote 30 A right of management means the power to construct and maintain the physical infrastructure necessary for, for example, exercising rights of access and withdrawal. A right of alienation empowers its holder to transfer ownership of the resource to another person or group. The bundle approach can be used to evaluate not only ownership itself but also other types of property rights, notably rights of use which were (and are) a common way of structuring rights in environmental resources. Often a right-holder (who may or may not be an owner) controls some of the component rights or shares control of these component rights with other individuals who use the same resource, for example, access to a river or withdrawal of water from a spring. The configuration of component rights varies situationally, depending on use of the resource as well as the interests of the right-holders.

This paper analyses rights in fresh water in Roman law using the environmental bundle as a guide, with a few other sticks from Honoré’s bundle, especially the ban on harmful use. The ‘bundle’ approach has opened new perspectives on property categories (public, private, common) in contemporary scholarship on rights in the environment, in particular, Elinor Ostrom's work on Common Pool Resource (CPR) theory.Footnote 31 CPR theory explains why some configurations of rights in common resources successfully mediate competition over resources (public or private), while others lead to the proverbial ‘tragedy of the commons’. Rather than a discreet legal category, a ‘commons’ is a resource, public or private, that is open to shared use, difficult to regulate, and diminished by use.Footnote 32 Common resources are usually regulated in some way, and the key question is, how are rights in them configured? The conditions for successful management of resources are that the rights regime be designed and implemented by local communities; in such systems, conflict is rare and easily resolved.Footnote 33 ‘Local’ community means the people who use the water, and group size is less critical to the success of a water regime than a community's ability to negotiate economic and social inequalities.Footnote 34 Similarly in the Roman world, ‘local’ water communities may be as small as two neighbours or as large as an irrigation community or a city. CPR theory offers a useful frame for Roman water rights because the dual nature of Roman public property corresponds to the modern concept of a commons. Also, in Roman law on private water rights, the jurists implement the principles of CPR theory often implicitly, as I have argued previously.Footnote 35 In this broader analysis of water rights, CPR theory explains the articulation of rights and, more generally, helps to diagnose problems in the regulation of both natural sources and aqueducts.

The aim of this paper is modest: to develop a conceptual basis for analysing conflicts over water, especially public water from both aqueducts and natural sources. Because the discussion focuses on legal rules and concepts, it is technical and idealizing to some extent, and its scope allows only a sketch of potential disputes. Indeed, rights regimes that fulfill CPR theory in contemporary communities often seem too good to be true. The competitive nature of Roman society, especially among its ruling élite, might seem to preclude the success of CPR solutions. But in fact social competition co-exists with and even strengthens the normative force of community designed rights regimes.Footnote 36 The configuration of rights in public sources is more prone to conflict, yet even here the Romans demonstrated an awareness of CPR principles, although they were not always able to apply them to minimize conflict over water, notably in the case of Rome's aqueducts.

The following discussion examines the configurations of rights to fresh water in four legal contexts, starting with ownership and servitudes (both governing private property) and followed by rights in civic aqueducts and public natural sources (public property). Analysing the component rights in fresh water reveals the underlying principles and priorities that guided the Romans' decisions about regulating this valuable resource. The analysis relies on a wide range of evidence: legal and historical literature, inscriptions, surveyors' writings, and Frontinus' treatise on the aqueducts. Combining such disparate evidence can be effective with careful contextualizing. The jurists' writings are especially important, not only because they are the primary source for the regulation of fresh water but also because they span the time periods of the other sources, providing a backdrop for continuity and change during the period of Classical Roman law (c. 27 b.c.–a.d. 235). For most of this era, until Caracalla's universal grant of citizenship in a.d. 212, the Empire was governed under mixed legal regimes: Roman citizens used the ius civile as did those with Latin rights while others relied on local or customary law. Roman property law applied only to land (and water) in Italy owned by Roman citizens. In the provinces, private property rights were defined by local law, while Roman public law governed most water resources because they were classified as public property. In these varied legal contexts, the jurists adapted water rights to local conditions, using the ius civile as a point of reference.Footnote 37 This process accounts for both their success in configuring water rights and the lack of a unified policy. It also generates some ambiguity in the notion of ‘local’, which may connote regional specificity or face-to-face groups (either small private groups or civic administration) or, in some cases, both. At the end of the Classical era, the jurists laid the groundwork for the co-ordinated regulation of water that emerges in later law and the imperial codes.Footnote 38 In the present paper, the bundle analysis of rights in fresh water shows that abstract property categories (e.g. public, private) are less significant for defining water rights than the articulation of component rights. This observation both clarifies our interpretation of Roman legal writings on water rights and corroborates scholarship on property rights in contemporary environmental law.

Ownership

In all periods of Roman law, water on the surface, underground, or collected in cisterns belonged to the landowner if the land was subject to ius civile ownership (dominium).Footnote 39 This was local control in the narrowest sense. The landowner held all five component rights in the environmental bundle: access, withdrawal, management, exclusion and alienation. These broad powers are justified by his interest in securing a supply to cultivate his land, but they are not unlimited. Landowners used various legal mechanisms to enforce their water rights, including the interdict quod vi aut clam and the actio de dolo as well as contracts of sale.

The landowner's rights to exclude others and control withdrawal can be traced to the Republican era through Pomponius' commentary on the writings of Quintus Mucius (cos. 95 b.c.). The case concerns the interdict quod vi aut clam and whether it could be used to protect water rights. With the interdict quod vi aut clam, a plaintiff could recover damages and costs to restore private property damaged by force or stealth.Footnote 40 In this case, the water had its source in an underground spring on land owned by one person (‘I’) although it emerged on land owned by another person (‘you’). What happens when you have diverted the water in some way (‘eas venas incideris’) so that it no longer comes to my land?

Si in meo aqua erumpat, quae ex tuo fundo venas habeat, si eas venas incideris et ob id desierit ad me aqua pervenire, tu non videris vi fecisse, si nulla servitus mihi eo nomine debita fuerit, nec interdicto quod vi aut clam teneris. (D. 39.3.21 Pompon. 32 ad Q. Muc.)

If water rises on my land that has underground sources from your estate, if you cut off those underground sources and for this reason water stops coming to me, you do not seem to have acted with force, unless a servitude is owed to me on this account, and you may not be bound by the interdict quod vi aut clam.

Both jurists agree that ‘I’ may not use the interdict unless ‘I’ have a servitude or a right to use water from ‘your’ spring.Footnote 41 By denying the interdict, they affirm that the owner of the land (‘you’) also controls withdrawal and access to the water beneath it, just as he owns other things above and below the surface of his land.Footnote 42

The owner's control of water rights is directly connected with his interest in cultivation already in Republican commentaries on the actio aquae pluviae arcendae (AAPA). The AAPA protected rural land from damaging run-off only if it was caused by human intervention (not natural causes). Exceptions were made for activities aimed at cultivating the land (fundi colendi causa) but, as Mucius wrote, a landowner should improve his own land without making his neighbour's worse, ‘sic enim debere quem meliorem agrum suum facere, ne vicini deteriorem faciat’ (D. 39.3.1.4 Ulp. 53 ad Ed.). The principle applied to both keeping water out and to managing water on one's land, as Ulpian makes clear in a case about a spring. After the landowner dug around a spring on his land, it stopped flowing down to his neighbour's land. To recover the water, his neighbour tried to bring an action on fraud (actio de dolo), but was unable to do so because this action required intent to harm.Footnote 43 To demonstrate the lack of intent, Ulpian suggests cultivation as an alternative motive, qualifying it with an echo of Mucius' opinion: his digging could divert the spring as long as he aimed at improving his own land not at harming his neighbour, ‘si non animo vicino nocendi sed suum agrum meliorem faciendi id fecit’ (D. 39.3.1.12 Ulp. [Mucius] 53 ad Ed.; cf. D. 43.24.7.7 Ulp. 71 ad Ed.). Improving the spring was equivalent to trenching around trees: both counted as cultivation (D. 39.3.1.5 Ulp. [Mucius] 53 ad Ed.). In fact, any work or construction around the water supply could be interpreted as an expression of the owner's right to the water, as suggested by Labeo in a case about a well. A landowner could use the interdict quod vi aut clam against a neighbour who polluted his well:

Is qui in puteum vicini aliquid effuderit, ut hoc facto aquam corrumperet, ait Labeo interdicto quod vi aut clam eum teneri: portio enim agri videtur aqua viva, quemadmodum si quid operis in aqua fecisset. (D. 43.24.11 pr. Ulp. 71 ad Ed.)

A person who poured something into his neighbour's well in order to pollute the water may be held by the interdict quod vi aut clam, as Labeo says: for fresh water is a part of the land, just as if he had done work on the water.

The phrase portio agri expressly identifies the water as part of the land, and Labeo's rationale connects the landowner's work with ownership of the water.Footnote 44

In addition to controlling the environmental bundle, the landowner also had exclusive right to alienate water sources on his land because it promoted agriculture. This right is confirmed by the treatment of servitudes, as will be discussed shortly, and also in inscriptions. For example, L.Vennius Sabinus gave to the town of Tifernum Tiberini a source and its water, ‘fontem et conceptum aquae’ (CIL XI.5942 = ILS 5761). An even clearer example of the right of alienation occurs in a long inscription recording the purchase by Mummius Niger Valerius Vegetus of a spring along with the land on which it arose, ‘cum eo loco in quo is fons est emancipatus’ (CIL XI.3003 = ILS 5771 ll. 5–6).Footnote 45 While outright purchase of a water source could incur high costs, it also provided the greatest security of the water supply for agricultural use as well as opportunity for additional profit from selling the water in turn to other users.Footnote 46 The owner also had a right to profits from the water when he delivered it in exchange for a fee.

Ownership afforded the landowner control of the environmental bundle of rights in water rising on or under his land. The rights of exclusion, withdrawal and management were assigned to the owner because they were directly related to the agricultural purposes served by the water: withdrawal and management contribute to cultivation while fruits represent its economic success. His broad authority was, however, limited by a prohibition on harmful use through the application of the actio de dolo and also in the AAPA. The prohibition provided a legal standard for negotiating conflicts that arose as neighbouring landowners exercised their bundle of rights. The owner's control of water rights was predicated on his interest in cultivation but it might not impinge on his neighbour's interest in doing the same.

Servitudes (Private Property, Rights of Use)

A servitude was a right of use that governed fresh water on private property. Three servitudes governed water rights: aquaeductus (the right to channel water), haustus (the right to draw water), and adpulsus pecoris (the right to water animals). They were treated as a type of property and were subject to the same legal mechanisms that applied to ownership.Footnote 47 Servitudes gave the right-holder nearly the same control of component rights as ownership. Like the landowner, the right-holder had legal power over access, withdrawal, management, fruits and alienation, as well as residual rights because these rights advanced agricultural productivity and encouraged local control of water sources.

The component water rights in servitudes and in ownership were treated similarly at least in part because servitudes developed from ownership. In its original form aquaeductus combined ownership of a water source with a right to channel the water across land owned by another person.Footnote 48 By the second century b.c. there were two other water servitudes, haustus and adpulsus, and all three were treated as incorporeal rights of use rather than corporeal property.Footnote 49 The servitude was attached to the dominant estate, whose owner (the right-holder) had a right to use resources on the servient estate, an adjacent parcel owned by someone else.Footnote 50 A servitude had no term, a component right that was the same in ownership.Footnote 51 The lack of term looks to reliability but it may also be related to agricultural productivity and local control, since it makes the water supply predictable and thus facilitates planning.

Most component rights were treated similarly in servitudes and ownership. But the owner of the source controlled the initial creation of servitudes through his right of access. He could grant as many servitudes as the source could support or, as Neratius wrote, ‘si … aquae sufficiens est’.Footnote 52 Neratius does not define sufficiens, ‘enough’, but the qualification implies that the water was already in use and that the landowner considered the impact of the new servitude on pre-existing uses, in particular his own interests in the water supply. To a modern reader, ‘enough’ might suggest sustainability in a broad sense, but for the Romans it was probably defined more narrowly in terms of agriculture, as the primary use of water.

Once a servitude had been created, the right-holder controlled the right of access just like the owner of the source.Footnote 53 When more than two parties shared a source, they comprised the local community that controlled exclusion and withdrawal.Footnote 54 When a new servitude was created on a shared source, all parties should be consulted, in addition to the owners of the source, as Ulpian advised ‘eorum in quorum loco aqua oritur verum eorum etiam ad quos eius aquae usus pertinet, voluntas exquiritur’ (D. 39.3.8 Ulp. 53 ad Ed.). They all shared the right to exclusion because each risked the negative impact of an additional servitude on his right of withdrawal, ‘cum enim minuitur ius eorum’.Footnote 55 Ulpian ends with a general comment putting right-holders and owners on an equal footing: both have a right to decide, whether their legal authority derives from ownership or a right of use, ‘sive in corpore sive in iure loci’.Footnote 56 Equating ownership and servitudes might seem inconsistent, but it offers several advantages: conceptual simplicity, ease of application, and equity among those sharing the water. Ulpian's approach assumes a local, face-to-face community in which water users configure the rights regime rather than a centralized state system.

Local control was a typical approach to rights of withdrawal in servitudes. When there were multiple servitudes, all right-holders co-ordinated allocation of water, exercising their respective rights of withdrawal. For example, they could arrange a schedule and could be flexible in its implementation, swapping days or times.Footnote 57 When informal negotiation failed, right-holders could negotiate using a legal remedy modelled on the action to divide jointly owned property (a remedy applicable first to ownership).Footnote 58 While the recourse to local control may reflect path dependence, it could still have provided incentives and opportunities for water users to plan and implement the rights regime effectively.Footnote 59 Comparative studies of water systems show that right-holders are more likely to follow the rules when they have a rôle in making them.Footnote 60 In turn, more effective enforcement of rights of withdrawal could also promote agricultural productivity by ensuring a more reliable water supply for farming needs.

Water servitudes, like other rustic praedial servitudes, were defined by their rôle in supporting cultivation of the land, as articulated by the jurist Paul in a case about adpulsus (D. 8.3.4 Papin. 2 Resp.). The priority of agriculture is reflected in the classification of these servitudes as res mancipi (D. 8.3.1.1 Ulp. 2 Inst.; Gaius, Inst. 2.17). Res mancipi was a type of property defined by a list of things essential to agriculture: slaves, beasts of burden, land in Italy and the buildings on that land, and rustic praedial servitudes.Footnote 61 Rustic praedial servitudes were likewise defined in relation to cultivation of the land.Footnote 62 In addition, when the interdict for daily and summer water (De aqua cottidiana et aestiva) was used to protect rights of withdrawal, irrigation was the primary use of water, as emphasized by Ulpian (D. 43.20.1.11 Ulp. 70 ad Ed.). When Labeo applied the interdict to hot as well as cold water, his rationale cited irrigation practice in regions where hot water was used to water the fields, ‘quod in quibusdam locis et cum calidae sunt, irrigandis tamen agris necessariae sunt, ut Hierapoli’ (D. 43.20.1.13 Ulp. 70 ad Ed.).Footnote 63 Labeo's opinion endorsed local control of water rights in the sense of regional specificity, although irrigation communities, ancient and modern, are typically face-to-face groups that configure and enforce their own rights regime.Footnote 64

The right of management in servitudes was also designed to promote a reliable water supply and, in turn, agricultural productivity. The right-holder controlled the right of management (viz. building and repairing infrastructure) because he (and not the owner of the source) bore the related risks and benefits. On the one hand, he could lose his right of withdrawal by non-use, if problems with the infrastructure prevented his exercise of the right.Footnote 65 On the other hand, because servitudes had no term, the right-holder had an incentive to maintain and even improve the infrastructure, knowing that he could enjoy a return on his investment in the long term. In fact, the economic incentive is assumed in an early case about improvements that enhanced agricultural productivity, for example, laying a pipe in order to spread water more widely, ‘quae aquam latius exprimeret’ (D. 8.3.15 Pompon. 31 ad Q. Muc.). Wider diffusion would increase cultivation and, hopefully, its financial returns. Mucius limited the right-holder's control over the physical structures with a prohibition on harmful use that protected the owner's water supply, ‘dum ne domino praedii aquagium deterius faceret’.Footnote 66 Such protection was critical to the owner's economic interests because management involved access and physical changes to his property. The prohibition on harmful use may also be connected with the rule that servitudes could be attached only to adjacent land.Footnote 67 The rule on adjacent land may first have arisen to protect intervening land owned by third parties with no rôle in the negotiations over the servitude. In all these situations, the prohibition on harmful use formalized expectations about local control of water and its economic potential.

In addition to the environmental bundle of rights, a servitude also included the right to profit which was defined by agricultural productivity, as articulated in disputes between the right-holder and the owner of the water source. In such disputes the parties used a modified version of vindicatio, the legal mechanism for resolving disputed ownership. There were two forms of action: the actio confessoria for the right-holder, and the actio negatoria for the owner of the source. Both parties could claim monetary compensation based on the fructus, ‘returns’ or ‘profits’, from the servitude:

In confessoria actione, quae de servitute movetur, fructus etiam veniunt. sed videamus, qui esse fructus servitutis possunt: et est verius id demum fructuum nomine computandum, si quid sit quod intersit agentis servitute non prohiberi. sed et in negatoria actione, ut Labeo ait, fructus computantur, quanti interest petitoris non uti fundi sui itinere adversarium: et hanc sententiam et Pomponius probat. D. 8.5.4.2 Ulp.17 ad Ed.

Profit comes in the actio confessoria brought for a servitude. But let us consider what profit there could be from a servitude. It is also more reasonable that there should be calculation on the account of profits, if the plaintiff has any interest in not being prohibited from exercising his servitude. But profit is also calculated in the actio negatoria, as Labeo says, by the value of the plaintiff's interest in the defendant's not using his land. Pomponius also endorsed this view.

For the owner of the dominant estate, fructus meant the cost of not being able to exercise his rights. For the owner of the servient estate, fructus meant the value of his land not being burdened with a right of use. Both costs and profits were measured in monetary terms calculated in terms of agricultural productivity in a case about aquaeductus (D. 8.5.18 Iulian. 6 ex Minicio). When the owner of the water source sent his slaves to interfere with his neighbour's servitude, the right-holder brought a legal claim for compensation to cover losses resulting from the lack of water. The examples in the case — dried up meadow or trees — show that economic costs and profits come from cultivating the land.Footnote 68

Economic interests also account for the treatment of the right of alienation in servitudes. In ownership, the landowner could alienate water on his land because it was considered part of the land. In servitudes, the right-holder also had the right of alienation, even though the source was not part of his land, because servitudes were transferred tacitly with the land, unless other arrangements were made.Footnote 69 Similarly, the right-holder could give a servitude as a pledge as if he owned it (D. 8.1.17 Pompon. 1 Reg.). Assimilating servitudes to ownership rewards the right-holder for effective management because he could sell (or pledge) his land for a higher price with water rights attached.Footnote 70 The higher price recognizes the economic value of the water supply itself and its reliability as guaranteed by the servitude. The treatment of alienation shows that water rights were treated as an economic asset, related to not simply agricultural productivity but also a more abstract notion of economic interest and profit.

The right of alienation created economic opportunities for the right-holder, although its implementation does not appear to have been part of a co-ordinated policy. First, it replaced local control with a strict rule that prejudiced the interests of the owner of the source. Sale of land could create an occasion for local control in renegotiating servitudes, but only if the purchaser of the land took the initiative. The owner of the source had no legal power to change the arrangement. Second, the impact of the rule was greater when the dominant estate was sold in parcels because the servitude went with each parcel along with a proportional amount of water.Footnote 71 The owner of the source suffered a disadvantage both legally and economically: both his legal power as owner and his interest in the water were ignored. His loss could be minimal in a simple sale, but when land was divided, changes in cultivation or the multiplication of users could decrease his water supply. By contrast, the right-holder had both advantages: legal control of the resource and economic power to negotiate a better sale price for his land because of its water supply. The treatment of alienation does not adequately take into account the costs and benefits of water servitudes. Moreover it is inconsistent with the principle of local control and promoting agriculture that guides configuration of the other component rights in servitudes.

While the treatment of component rights in servitudes is not entirely systematic, the legal opinions consistently emphasize local control of resources and promotion of agricultural productivity. The right-holder co-ordinated rights of access, withdrawal, exclusion and management with the owner of the sources and, when necessary, with other right-holders. While this balancing of rights among the parties may reflect a legal principle it also had a significant practical impact of allowing those who used the water to define and enforce the rights to it. Law was a tool of landowners and local communities who had the best knowledge about private water sources and the economic interests that depended on them.

III CIVIC AQUEDUCTS

Civic aqueducts, whether in Rome or other cities of the Empire, were public property, and the state monopolized the component rights of access, exclusion, withdrawal, management and alienation.Footnote 72 Rights of access and withdrawal were assigned to private individuals by the state, as a mark of honour or in exchange for a fee. Such individual grants were different from servitudes because they were personal, not property rights, and the state retained control of exclusion and alienation.Footnote 73 The rights regime in civic aqueducts had a dual nature: water was both regulated and unregulated, that is, it flowed continuously to open-access fountains. The rights regime thus served conflicting priorities. Maximizing the water supply was a clear priority, connected with the health and safety of the city.Footnote 74 Civic aqueducts were also used to reinforce social and political hierarchies. The configuration of component rights in the water from the aqueducts reflects both the co-ordination and divergence of these priorities. The evidence for component rights comes largely from Frontinus' treatise but is corroborated by inscriptions and literary evidence.

Aqueducts in the Republic

Evidence for component rights in civic aqueducts begins with the right of management in the construction of the aqueducts by the censor Ap. Claudius Caecus in 312 b.c. and M’. Curius Dentatus in 272 b.c. The senate had some authority over management through its control of financing, although these two censors acted independently: Claudius reportedly spent public funds on the aqueduct without senate approval, and Curius financed construction ex manubiis.Footnote 75 In the second century b.c. elected magistrates had authority over the right of management as well as access, exclusion and withdrawal. In 184 b.c. the censors M. Porcius Cato and L. Valerius Flaccus cut off illegal withdrawals of water from the aqueducts, ‘aquam publicam omnem in privatum aedificium aut agrum fluentem ademerunt’ (Livy 39.44.4).Footnote 76 These historical accounts of rights in the aqueducts are corroborated by Republican statutes quoted by Frontinus and by the so-called lex Rivalicia.

The Republican statutes reported by Frontinus outline the state monopoly on the component rights in water from the city aqueducts.Footnote 77 The first of these laws concerns the censors' control of rights of access, withdrawal and exclusion, and assigns the same powers to aediles when no censors were in office.Footnote 78 These magistrates regulated grants to privati, that is, they were empowered to assign rights of withdrawal to private individuals. Although their legal power is framed in terms of sale, ‘ius dandae vendendaeve aquae’, the water was not alienated, i.e. there was no transfer of ownership; instead rights were arranged by contract in exchange for a fee for use.Footnote 79 The magistrates' right to assign private withdrawals was, however, limited, because these rights could be assigned only on overflow water, aqua caduca, and only to particular groups: baths and fullers (who paid a fee for use), and to leading men (whose right of withdrawal was a mark of honour).Footnote 80

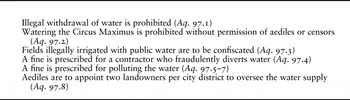

The right of withdrawal was the main focus of a Senatus Consultum of 116 b.c. which also addressed access and management (Aq. 97; summarized in Table 1).Footnote 81 The Senatus Consultum confirms the rôle of censors and aediles in controlling withdrawal inside and probably outside the city (Aq. 97.2–3). It prescribes a penalty for contractors to deter illegal withdrawals (Aq. 97.4). This penalty implies the right of management as well, since the censors contracted and approved repairs and maintenance. The prohibition on pollution regulates the right of access (Aq. 97.5–7). The magistrates exercised their rights indirectly through the neighbourhood deputies appointed in the last provision. These deputies were responsible for the open-access public basins, ‘in publico saliret’, and they may be identified with the montani and pagani who are mentioned in another Republican statute, the lex Rivalicia.Footnote 82

Table 1 Summary of the Provisions of the Senatus Consultum of 116 b.c. in Front., Aq. 97

The lex Rivalicia is known from a partial quotation in Festus' definition of sifus, ‘siphon’ (Festus 458L). This statute may have been a lex Sulpicia, proposed by and named for the consul of 50 b.c., the jurist Servius Sulpicius Rufus, if this is the correct restoration of the text.Footnote 83 Festus refers to it as lex Rivalicia, for its subject, rivi or water channels that carried their water in the city.Footnote 84 It assigns legal power, iurisdictio, over water use to montani and pagani:

‘Siphon’ — the word that is called σίφων in Greek — is used in public laws and it is written in the lex Rivalicia that Servius Sulpicius proposed to the people about the use of water: ‘montani and pagani’ shall … as long as this [law] among them … there will be power of granting judgement.

Iurisdictio usually refers to a magistrate's authority to issue judgement in a legal action, but here it is interpreted to mean rights of withdrawal and management.Footnote 85 The magistrates, montani and pagani, administered rights of access and withdrawal, possibly to collect the fee for use, as they are otherwise connected with the census and finance.Footnote 86

The treatment of component rights in the Republican statutes offers indirect evidence for their policy aims. For example, the prohibition on pollution in the SC of 116 b.c. promoted water quality.Footnote 87 Maximizing the city supply emerges as a clear priority in the treatment of rights of withdrawal. In the SC of 116 b.c., the penalties for contractors and the prohibition on illegal irrigation also aim to maximize supply to the city, and may reflect tension between urban and extra urbem supply.Footnote 88 The relative size of the penalty for illegal irrigation indexes the seriousness of the offence as measured by its impact on the supply of water to the city.Footnote 89 Even the rights of withdrawal assigned to baths and fullers might serve this policy.Footnote 90 The rights assigned to leading men, however, decrease the supply for other residents and instead reinforce social and political distinctions.Footnote 91 The regulation of withdrawal and its divisive impact seem to preclude a policy of local control for city aqueducts. Yet local control is institutionalized in Republican law and practice. The first Republican law affirms local control within the face-to-face society of the senate, since the élite controlled honorary rights of withdrawal by granting (or withholding) consensus, ‘concedentibus reliquis’.Footnote 92 Both the SC of 116 b.c. and the lex Rivalicia authorize institutional forms of local control. In the SC, aediles appoint neighbourhood deputies to administer water rights who must either reside or own property in the neighbourhood, ‘qui in unoquoque vico habitarent praediave haberent’ (Aq. 97.8). The alternative hints at the challenges posed by implementing the rights regime in the city aqueducts. Resident deputies, like those who shared private water sources, had a common interest in enforcing the system, while non-resident élites might exploit their influence to undermine the system. The montani and pagani in the lex Rivalicia probably played a similar rôle, that may also be connected with the rôle of pagani in a Spanish irrigation community, as documented in the Hadrianic lex rivi Hiberiensis. But the difference in context, rural versus urban, advises caution about assuming a similar rôle for the montani and pagani in Rome. Where the rural pagani were members of the irrigation community who used the water themselves, in Rome the montani and pagani were city officials administering water rights with no necessary personal stake. In other words, Roman city administration attempted to institutionalize the local control of water rights, but creating an administration undermined or at least redefined local control, replacing face-to-face negotiation with officials who might only abstractly represent the shared interests that informed effective water rights.

Aqueducts in the Empire

In the Empire, the state maintained a monopoly on water rights with similar priorities as in the Republic. The imperial rights regime was organized during the reign of Augustus (27 b.c.–a.d. 14), starting in 33 b.c. when Agrippa was aedile.Footnote 93 Like a Republican aedile, Agrippa controlled the rights of access, withdrawal and management. He systematized the right of withdrawal by organizing it into three categories: publica opera, lacus, grants to privati.Footnote 94 He also regularized the system of grants to privati and introduced a standard pipe for delivery in the city (the quinaria), which regulated withdrawal by providing a measurable standard.Footnote 95 Agrippa exercised the right of management by building three new aqueducts and repairing the older ones.Footnote 96

After Agrippa's death, Augustus consolidated control of water rights in the person of the emperor. He assumed the censors' right of management by personally seeing to the repair and expansion of the aqueducts, as he boasted in the Res Gestae (20).Footnote 97 He also inherited Agrippa's slave crew and made it public property (Front., Aq. 99.1). Augustus endorsed Republican regulation of withdrawal (for example, restrictions on watering the Circus Maximus, Front., Aq. 97.2) and authorized Agrippa's system for administering the right of withdrawal in grants to privati. Additionally, he created the position of curator aquarum to take the rôle of Republican magistrates and exercised the right of withdrawal through delivery to imperial property and grants to privati (Front., Aq. 99.3–4).

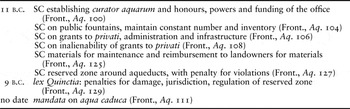

Augustus' reform of the water regime in the aqueducts was authorized by a series of senatus consulta in 11 b.c., the lex Quinctia in 9 b.c., and undated imperial mandata (listed in Table 2). The first SC established the new position of the curator aquarum whose control of the component rights is implemented through the other Augustan laws. The lex Quinctia authorized the curator aquarum to exercise rights of access, withdrawal and management as well as to enforce the law (Front., Aq. 129.5, 9, 11). Three of the SC — fountains, maintenance, reserved zone — confirm the state's control of management (Front., Aq. 104, 125, 127). The SC on fountains along with the one on grants to privati implement withdrawal and access (Front., Aq. 104, 108). A separate SC, prohibiting transfer of grants to privati, shows that the state also controlled alienation: as Frontinus explained, when a water grant expired, it reverted to the state for reassignment (Front., Aq. 108. 109.1). This overview of the senatus consulta demonstrates the state monopoly on component rights. Further analysis reveals the priorities that this water regime advanced.

Table 2 Augustan Statutes on the Aqueducts

Securing the water supply of the city was an overarching priority of the imperial system. The rights of access, withdrawal and management are co-ordinated in five of the seven statutes (Front., Aq. 104, 106, 125, 157, 129). The decrees about maintenance, the buffer zone and damage secure the supply to the city by protecting the physical fabric of the aqueducts (Aq. 125, 127, 129).Footnote 98 The decree on grants to privati also connects withdrawal and management because grants to privati were defined by the pipe size and restricted to specific locations, i.e. not from the rivus but from a castellum (Aq. 106.3). A complementary administrative procedure ensured that the physical specifications were implemented accurately and honestly (Front., Aq. 105). Finally, the SC on fountains tasked the curator with maintaining the operation and stock of fountains (Front., Aq. 104.2, cf. 78–86 for the number of fountains). The right of management is thus deployed to both secure and maximize access to water for residents of the city, as suggested by Frontinus' emphasis on the constantly flowing fountains.

Frontinus' praise of Nerva sends the same message. Nerva's crack down on fraud in grants to privati is comparable to constructing more fountains for public access, which he also did, ‘haec copia aquarum … quasi nova inventione fontium accrevit’ (Aq. 87.1, cf. 88.1). The increased supply implicitly augments grants to privati by making them more secure (Aq. 88.2). Even improved water quality is a by-product of increased supply (Aq. 88.3, 94.1). ‘Bigger is better’ works as rhetorical strategy both for Frontinus and for Nerva himself: more water and more hydraulic infrastructure enhanced the reputation of both men.Footnote 99 Moreover, Frontinus' rhetoric demonstrates that maximizing the supply depends on the state's monopoly of water rights.

While the evidence for component rights gleaned from Frontinus points to a primary policy of maximizing supply to the city, the rights regime also supported deliveries outside the city. In fact, these two priorities — city supply and deliveries outside the city — were linked, and not only in the problem of illegal taps. Frontinus' treatment of the Aqua Alsietina hints at co-ordinated policy. At first he confesses that he is baffled by Augustus' decision to build the Alsietina because it earned no good and its water was of poor quality and not accessible to the people (Aq. 11.1). Then he discovers a rationale: construction of the Alsietina helped to maximize and improve the city supply by leaving better quality water for consumption, expanding delivery across the Tiber, and increasing irrigation outside the city (Aq. 11.2). This rationale, however ex post facto, implies that imperial policy included promoting agriculture in and around the city.Footnote 100 Frontinus' data show that the aqueducts delivered about a third of their water outside the city.Footnote 101 Archaeological evidence confirms the pattern, although it cannot distinguish illegal taps, which would challenge the policy.Footnote 102 The state's co-ordination of management and withdrawal may have aimed to mitigate conflict between urban and extra urbem delivery, balancing the needs of agriculture and city residents. Yet the persistent problem of illegal taps shows that the rights regime was not entirely successful, probably because the urban/rural divide further undermined the notion of a local community around the city aqueducts. Two separate communities (rural and urban) shared water from the aqueducts, and neither one had unified control over the rights regime and its implementation.

Corroborating evidence for policy on Rome's aqueducts comes from civic aqueducts in other cities of the Empire documented in inscriptions: the Tabula Contrebiensis (AE 1979, 377), the municipal law from the triumviral colony at Urso in Spain (CIL I2.5) and the decree from Venafrum in Italy that records the regulation of an aqueduct built for the city by Augustus (CIL X.4842).Footnote 103 The Tabula Contrebiensis (89 b.c.) is earlier than the other two laws and different in nature, concerning only the right of management because it negotiates the purchase of land for a civic aqueduct, using legal fictions to adapt Roman law to local law.Footnote 104 In Urso and Venafrum, the state monopolized the component rights in the water supply, but instead of Roman authorities, local magistrates (duoviri or aediles) controlled the rights of exclusion, access and management.Footnote 105 The system was probably modelled on Rome's. In the Urso law, attention to aqua caduca suggests a parallel with Rome's administration.Footnote 106 The Venafrum decree describes administration similar to what Frontinus reported for Rome: repairs and the reserved zone (ll. 1–29), penalties for damage and respect for property along the route (ll. 29–35), grants to privati and regulations on infrastructure (ll. 36–47), as well as legal procedure for resolving disputes (ll. 47–59).Footnote 107 Individual rights of withdrawal were arranged on the same bases as at Rome, as an honour or in exchange for a fee.Footnote 108 As at Rome, the rights of withdrawal and management were co-ordinated to enforce the state's control of the water supply.

At Urso and Venafrum supplying the city was the main priority but the state monopoly on component rights was attenuated to some degree by local control. In the Venafrum decree, the policy of maximizing supply to the city is expressed explicitly through the right of management in a prohibition on damage to the infrastructure:

neve cui eorum, per quo|rum agros ea aqua ducitur, eum aquae ductum corrumpere abducere aver|| tere facereve, quominus ea aqua in oppidum Venafranorum recte duci| fluere possit, liceat. (CIL X.4842.33–5)

Nor is it allowed for any of the people whose fields the aqueduct crosses, to break, withdraw, divert or do anything that makes it impossible for water to be channelled or to flow directly into the town of Venafrum.

The Urso law likewise prohibits interference with the infrastructure, but without mention of the city expressly, ‘quo minus ita/aqua ducatur’ (CIL I2.5, ch. 99). Similar language is used in the Tabula Contrebiensis to justify construction, ‘rivi faiciendi aquaive ducendae causa’ (l. 2). For Rome's aqueducts, neither the lex Quinctia nor the senatus consulta expressly connect management with supply to the city, although the connection is implicit in Frontinus' emphasis on repairs and maintenance. As for local control at Urso and Venafrum, the rules on management reflect the same rural/urban split in the local community, granting the city control over water in its rural territory. The language of the law, however, complicates the picture, revealing a layered approach to community. The phrase, ius potestasque, is used to designate legal authority over component rights in both laws and also in the lex Quinctia on Rome's aqueduct, but it refers to different rights and different right-holders. While the Urso law (ch. 99) and the lex Quinctia (Front., Aq. 129.5) grant this power to city officials, the Venafrum decree grants it to citizens, ‘earumque rerum omnium ita habendarum || colon(is) Ven[afra]nis ius potestatemque esse placet’ (CIL X.4842.29–30).Footnote 109 It is possible that the coloni are meant to stand in for the town's magistrates, but if not, the Venafrum decree creates a broader community that could even include coloni who owned rural land. Thus, treatment of management in the Venafrum decree involves a local community in which civic regulation works like private water rights, in contrast to the divided community at Rome (and probably Urso). But not all control was local, because the decree also refers disputes to the court of the praetor peregrinus at Rome.Footnote 110 This added level of administration interfered with the local community's control of component rights, likely imposing the status rift that characterized Rome's aqueduct administration.Footnote 111

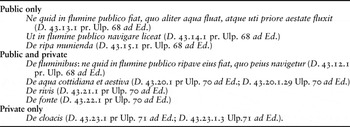

Table 3 Interdicts relating to Water Sources with References to their Wording and Scope

Similar layering of authority and community is evident in provincial administration, as reported in Pliny's letter about the construction of an aqueduct at Sinope. When Pliny reports that he has financed some assays to determine whether the ground can support the aqueduct, Trajan supports Pliny's plan but insists that the town foot the bill.Footnote 112 Exercising the right of management required financing, both at Sinope and for Rome's aqueducts (e.g. Front., Aq. 118). In provincial cities, the articulation of component rights may involve a broader notion of public that includes citizens as well as magistrates in a local community. How local the community depends on whether these citizens had rights comparable to those of the montani and pagani in Rome or to the pagani in the irrigation community on the Ebro, who were more like owners than civic officials. If the citizens of Venafrum were responsible for maintaining the stretch of aqueduct that passed along their property (as was usual for public roads), the line between public and private rights of management is further blurred.Footnote 113

Both in Rome and in provincial cities, the component rights in civic aqueducts were configured to secure the water supply of the city through a state monopoly. Civic officials (curator in Rome, magistrates elsewhere) were empowered to assign rights of access and withdrawal to private individuals but these were temporary arrangements, sometimes in exchange for a fee, as in a lease. These grants to privati could reinforce the social hierarchy or they could advance economic aims by supplying irrigation in and around the city, just as private water rights did. In addition, the rights regime in civic aqueducts also had a measure of local control, although this was more limited than for private water rights. More intersection with private water rights is found in the treatment of public natural sources.

IV PUBLIC RIVERS AND OTHER NATURAL SOURCES

As the section heading indicates, public natural water sources were varied — lakes, streams, springs, rivers. For the most part, their status followed that of the land where they were found.Footnote 114 Public rivers, however, were defined as perennial or flowing year round by the first-century a.d. jurist Cassius, and this definition became standard in Classical Roman law.Footnote 115 Public rivers dominate the evidence for the rights regime of public natural sources because of their place in both law and policy: rivers were important to the development of interdicts on water and also to the economic aims served by this rights regime. Yet all fresh water sources were usually grouped with rivers in the legal discussions, even though some policy issues relate only to rivers (e.g. boat traffic).Footnote 116 The interdicts are the main source for rights in public fresh water, and they are supplemented by inscriptions, literature and surveyors’ treatises. A list and description of the interdicts is presented as an appendix.

The earliest evidence for an interdict regulating fresh water is an inscription from northern Campania dating to the second half of the second century b.c. (CIL X.8236).Footnote 117 In the inscription, one Q. Folvius records his use of an interdict authorized by the urban praetor P. Atilius to protect his right to water:

Quintus Folvius, son of Quintus, grandson of Marcus claims a right to this water in the court of P(ublius) Atilius, son of Lucius, the urban praetor.

Both the verb indeixsit and the presence of the praetor point to an interdict as the relevant legal mechanism but not the specific interdict. Nothing in the text identifies the water sources as public or private, although the findspot, near the remains of a small aqueduct in a rural area, suggests private property.Footnote 118 Folvius used the interdict to claim a right of access and/or withdrawal and probably also to exclude others.

Despite its lack of detailed context, the Folvius inscription effectively represents the state's use of interdicts to control component rights in natural sources and to assign them to private individuals.Footnote 119 The senate and subsequently the emperor shared this legal authority.Footnote 120 For the interdicts, the praetor's rôle was jurisdictional, not administrative, in that he did not supervise a system like the grants to privati in civic aqueducts. The praetor took action only in response to complaints from private individuals.Footnote 121 By giving a judgement in a legal dispute he created and affirmed an individual's right to use water. These rights were analogous to servitudes in Classical law, even though they could be created on both private and public water.Footnote 122 For private water, the interdict was a procedural alternative to the actio confessoria (used for servitudes). The interdict also protected individuals with an interest in water but no formal servitude, whether the water was public or private.Footnote 123 Public rivers were explicitly characterized as open access, by analogy with public roads and the seashore, and the right of withdrawal was available to everyone without a servitude.Footnote 124

The rights regime in public natural sources was thus characterized by the same duality between open access and regulation as civic aqueducts. This duality was resolved in post-Classical law when all public water was regulated through administrative grants.Footnote 125 Throughout the period of Classical Roman law, however, jurists perceived no contradiction in regulating an open-access resource such as public water, just like a modern commons.Footnote 126 Although there was no systematic approach, several issues guided the regulation of public rivers, including boat traffic, irrigation, local control, and the Roman state's interest in tax revenue from activities that depended on the water supply. Discussion of these issues tends to arise when there is conflict between different uses of water or between local control and the interests of the Roman state. Most of the evidence comes from the provinces, either due to accidents of survival or questions arising from the mixed rights regime or attention to the state's fiscal interest: taxes were collected primarily in the provinces. Typically, Roman law endorsed local configurations of water rights in natural sources, authorizing not only face-to-face local control but also local institutional control (similar to the civic aqueduct community at Venafrum). Policy issues, occasionally articulated, are more often implicit in the countours of the conflict.

Boat traffic is the first clearly articulated policy aim. Three interdicts specify boat traffic as a protected activity in their formulas (Ut in flumine, De ripa munienda, De fluminibus).Footnote 127 The protection of boat traffic implies a conflict with other activities, especially those depending on rights of withdrawal. Romans expected river water to be diverted for productive use, an assumption exploited by one of Plautus' clever slaves to justify theft with an analogy comparing money and river water: unless a river is diverted it runs useless to the sea: why not, he implies, take the money and put it to good use (Plaut., Truc. 561–7). The jurists also recognized that productive diversion merited protection. For example, Labeo extended the Ne quid in flumine publico to non-navigable rivers to protect productive activities.Footnote 128 But diversions caused conflict by lowering the water level, precisely the problem anticipated by Labeo's opinion that the praetor ought not to assign a right of withdrawal on navigable rivers (D. 39.3.10.2 Ulp. [Labeo] 53 ad Ed.). Ulpian generalized the rule for all rivers, authorizing the interdict only when diversions did not affect the flow of water.Footnote 129 He frames this limit as a ban on harmful use: any right of withdrawal must not cause foreseeable injury or inconvenience to the locals.Footnote 130 If it does, they will have recourse to the interdict to protect their interests. Conflict among those holding rights of withdrawal is also addressed in a rescript from the Antonine era concerning a conflict between irrigation and other unspecified uses of a public river (D. 8.3.17 Papir. 1 Const.). Apparently, when local control failed, the case came to the emperor, who was unable or unwilling to resolve the dispute. The rescript asserts a ban on harmful use, but does not rule on the dispute between the irrigators and other right-holders, returning the problem to local negotiation. ‘Local’ here probably means a community in the provinces, where the jurists adapted private law and the interdicts to configure rights in public rivers.Footnote 131 Irrigation in a provincial context suggests a motive for the Roman state to intervene, namely, tax revenue derived from irrigated farmland. Indeed, both the rescript and Ulpian's approach recognized that rights to withdrawal could serve irrigation and other productive aims, although these aims are not consistently protected. Instead tension between local control and state interest charaterizes the treatment of natural water sources in both literary and epigraphical evidence.

The tension between local control and the Roman state's interests appears in a late Republican conflict over the river Darias in northern Italy. When the Romans established a garrison at Eporedia around 100 b.c., they seized gold mines there from the Salassi and leased them to the publicani. The Romans were, however, unable to take control of the river Darias, which supplied water both to process gold and to irrigate downstream farmland. The Salassi held the mountain highlands and earned revenue by collecting tolls and selling the river water to the publicani.Footnote 132 They controlled rights of access and withdrawal, and implemented them to their own advantage. When they diverted the river into secondary canals for gold processing, they deprived farms in the plains of water for irrigation:

προσελάμβανε δὲ πλεῖστον εἰς τὴν μεταλλείαν αὐτοῖς ὁ Δουρίας ποταμός, εἰς τὰ χρυσοπλύσια, διόπερ ἐπὶ πολλοὺς τόπους σχίζοντες εἰς τὰς έξοχετείας τὸ ὕδωρ τὸ κοινὸν ῥεῖθρον ἐξεκένουν. τοὺτο δ᾽ἐκείνοις μὲν συνέϕερε πρὸς τὴν τοῦ χρυσοῦ θήραν, τοὺς δὲ γεωργοῦντας τὰ ὑπ᾽αὐτοῖς πεδία, τῆς άρδείας στερουμένους, ἐλύπει, τοῦ ποταμοῦ δυναμένου ποτίζειν τὴν χώραν διὰ τὸ ὑπερδέξιον ἔχειν τὸ ῥεῖθρον. ἐκ δὲ ταύτης τῆς αἰτίας πόλεμοι συνεχεῖς ἦσαν πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἀμϕοτέροις τοῖς ἔθνεσι. (Strabo 4.205 (4.6.7))

The river Darias gave the most advantage to them in mining for washing gold, and for this reason they diverted the water into sluices in many places emptying the main channel. While this helped them in the pursuit of gold, it harmed the farmers of fields below them because they were deprived of irrigation, although the river was able to irrigate the land because its course ran on higher ground. For this reaon there was constant hostility between the communities.

Their diversions lowered the water level in the main channel, just as anticipated in the interdicts. Strabo's description of the main channel, τὸ κοινὸν ῥεῖθρον, is suggestive of open access, characterizing the physical river with an idealizing image of shared water.Footnote 133 But instead of ideal sharing, the Salassi exploited their control of component rights to the disadvantage of the farmers, the publicani, and ultimately the Roman state which was interested in tax revenue from the gold. Recurrent conflict over the river Darias provided a ready pretext for repeated Roman military intervention which culminated in Augustus' foundation of a veteran colony, Augusta Praetoria, in 25 b.c.Footnote 134

The state's interest in the Darias is implied in Strabo's account, but the early imperial jurists Labeo and Sabinus made it explicit in a legal opinion about fishing rights in a lake. While fishing rights are not the same as withdrawal of water, they represent an analogous legal conflict over use of water. A publicanus had a contract with the state to fish a lake or lagoon; when he was prevented, he sought an interdict to protect his right. The jurists allowed him not the interdict itself but an analogous interdict. That is, the publicanus did not have the same standing as a right-holder (who could use the interdict) but his interests warranted the same protection, presumably because his circumstances were similar to those of right-holders; if Labeo and Sabinus gave a rationale, it was lost in compilation.Footnote 135 Ulpian, who cites their opinion, does give a rationale and he also extends the interdict's protection to contracts with municipia (not just with Rome itself): ‘ergo et si a municipibus conductum habeat, aequissimum erit ob vectigalis favorem interdicto eum tueri’ (D. 43.14.1.7 Ulp. 68 ad Ed.). The extension to municipia not only emphasizes the financial motive but also locates the case in the provinces where most natural sources of water were public property. While there is no rescript or constitution on this issue, Ulpian's rationale likely represents imperial policy, showing that local control was limited by Rome's revenue interest.Footnote 136 Nevertheless, local control seems to have been the usual approach to rights in natural sources in the provinces.

The Romans typically endorsed pre-existing property regimes in conquered territory. Augustus advocated for local control of colonial boundaries, although it is not known whether he mentioned water rights specifically because his speech is known only from a paraphrase in a surveyors' treatise.Footnote 137 These treatises also recommend preserving prior arrangements for fresh water resources as far as possible.Footnote 138 Inscriptions confirm the practice. First, the municipal law from Urso in Spain regulated natural sources: streams, springs, lakes, ponds, swamps and probably rivers.Footnote 139 It endorsed the pre-existing legal regime by granting the same rights of access and withdrawal to current owners and possessors as had been held before:Footnote 140

qui fluvi rivi fontes lacus aquae stagna paludes / sunt in agro, qui colon(is) h[ui]usc(e) colon(iae) divisus / erit, ad eos rivos fontes lacus aquasque sta/gna paludes itus actus aquae haustus iis item / esto, qui eum agrum habebunt possidebunt, uti / iis fuit, qui eum agrum habuerunt possederunt. / itemque iis, qui eum agrum habent possident ha/bebunt possidebunt, itineris aquarum lex ius/que esto.vacat (CIL I2.5 ch. 79, tab. a Col. II.39–40 and tab. b. Col. III.1–7)

Rights of approach and access to and a right of withdrawal from those streams, canals, springs, lakes, ponds, and lagoons that are in the territory which was allocated to colonists of this colony, shall belong to those who will have and hold this land, as they belong to those who used to have and hold it, and likewise the right and legal authority over channelling water shall belong to those who have and hold and will have and will hold this land.

The charter affirms the local configuration of water rights and assimilates them to Roman private law, using the language of servitudes, ‘itus actus (access), aquae haustus and itineris aquarum lex ius/que esto’. The status of the water is not indicated, but the law probably applied to both public and private sources, much as the praetorian interdicts did.Footnote 141 The legal logic may derive from the interdicts, which could be used by owners and non-owners alike to protect rights in both public and private water.Footnote 142

Two other inscriptions show the same pattern. First, the Hadrianic lex rivi Hiberiensis (lrH) established an irrigation community on a canal (the rivus Hiberiensi, lrH para. 1, I.1) fed by the river Ebro in north-eastern Spain.Footnote 143 The decree was enacted to resolve a dispute between upstream and downstream irrigators.Footnote 144 Second, an early third-century a.d. inscription documents an irrigation community near Lamasba in North Africa (CIL VIII.18587 = 4440 = ILS 5793). In both inscriptions, the Romans endorse local control of component rights in public water sources, formalizing and strengthening local arrangements with Roman law.Footnote 145 For example, they confirm rights of withdrawal to individuals who used the water.Footnote 146 In the lrH, the local community also controlled the right of management and exclusion, although ‘right’ may be something of a euphemism for management since the decree imposes a penalty for failure to perform maintenance.Footnote 147 Neither inscription explicitly identifies the water as public or private, but Roman private law seems to be the model in both places.Footnote 148 Circumstances of both inscriptions suggest that irrigation served land subject to taxation. At Lamasba, the Roman authorities played a smaller rôle than in the lrH which was sanctioned by the governor's legate who may also have been responsible for its skilful adaption of Roman law.Footnote 149 Further, the Ebro irrigation community was organized as a pagus, an adminstrative unit that was used to organize tax assessment, and the publicani had a rôle in enforcing the lrH that may reflect their interest in the system (paras 8 and 9, II.43–54, III.1–2). Thus the irrigation inscriptions document Rome's endorsement of local control but may also represent effective manipulation of local water rights to achieve Roman fiscal priorities.Footnote 150

Financial concerns also led the Roman authorities to intervene in local rights of management when the construction of new hydraulic infrastructure was at stake. In these cases, local means local governments that were more like large irrigation communities than the one-to-one neighbour relationships in servitudes. For example, when Pliny was governor of Pontus-Bithynia, he consulted with Trajan about the construction of a canal at Nicomedia. Pliny took a supervisory rôle, while local officials managed both financing and logistics for the project. Trajan's concerns were primarily fiscal: he urged curbing cost over-runs, while delegating both the right to manage the infrastructure and financial responsibility to the Nicomedians.Footnote 151 Hadrian's project at Lake Copias in Boeotia followed a similar pattern, with policy aims articulated in an inscription that demonstrated the emperor's ‘awareness of the project's agricultural benefits, expense, and (perhaps) potential ramifications, and his care to involve the Coroneans in the enterprise’.Footnote 152 In both projects, the right of management was exercised by local government with supervision by the emperor. Tensions over rights of management arose when local control threatened Rome's finances, as with rights of withdrawal. Imperial policy seems focused more on financial impact than on configuration of water rights.

Rights in natural public sources were articulated in relation to the varied legal regimes in Italy and the provinces. Where the ius civile applied, the praetor controlled rights of access, withdrawal and exclusion through the interdicts, and assigned these rights to the individuals who used the water. In the provinces, Roman law institutionalized local water regimes, assimilating them to servitudes, sometimes in face-to-face communities, sometimes through civic administartion. The right of management was implemented in the same way. The ban on harmful use was defined in terms of local practice as it was for private water rights, since those who used water from a public river were required to take each other's interests into account. Instead of monopolizing the component rights, Roman policy promoted local control while intervening to assert state authority when disputes arose or to promote its financial or ideological interests.

V CONCLUSION

This analysis of component rights reveals significant continuities in the treatment of water from both private and public sources that transcend property categories. The categories of public and private property were not consistently associated with distinct configurations of component rights. For the most part, jurists and lawmakers subordinated abstract legal concepts to the needs and interests of the people who relied on fresh water for economically productive uses, especially agriculture.

The rights regime of public natural sources intersects both private water rights and the administration of civic aqueducts (also public water). The most extensive overlap occurs between three legal contexts: ownership, servitudes and public natural sources. For all three, the rights of withdrawal, exclusion and management were exercised by the individuals who used the water, and local control was the working principle. In ownership and servitudes, the water users held these rights and exercised them directly. For public natural sources the state had a nominal monopoly on component rights but in practice assigned rights of access, withdrawal and exclusion to the individuals who used the water, sometimes in exchange for a fee. The right of alienability was also handled in the same way in these three types, probably because these water rights were attached to land and transferred with ownership of the land. In these three contexts, water rights were also limited by a prohibition on harmful use, despite the fairly broad rights of owners on the one hand and on the other the expectation that public natural sources would be open-access. For all types of water, the right of management was always co-ordinated with rights of access and withdrawal, probably because the Romans recognized that a legal right to water was useless without the infrastructure to exercise it. Or as the Classical jurist Venuleius wrote, ‘quando non refectis rivis omnis usus aquae auferretur et homines siti necarentur’ (D. 43.21.4 Venul. 1 Interdicts).

The similar treatment of all public sources (natural or aqueducts) lends a new unity to the category of public property. The rights regime created through praetorian interdicts resembles that of civic aqueducts in that both assumed a state monopoly on component rights as well as a dual system of regulation and open access. But the regulation of public natural sources was different from that of aqueducts because it overlapped with private water rights and was driven by private interests in water. Civic aqueducts were strictly regulated, and magistrates and emperors directly exercised component rights in their water. The state did assign rights of withdrawal and access to private individuals, but retained the rights of exclusion, management and alienability. For public natural sources, as previously described, the entire bundle of component rights was typically exercised by the individuals using the water while the state intervened only to resolve disputes or protect the state's interests, typically financial. The state's monopoly on civic aqueducts is probably to be explained by policy and ideology. Frontinus assumes that maximizing supply to the city justifies tight regulation, even though he also recognizes both the inadequacy of centralized administration and its ideological bias. Ideology offers a more persuasive explanation for strict regulation, because civic aqueducts were deeply embedded in social and political institutions. This is not to say that social and political factors did not influence private water or public natural sources. But for civic aqueducts the legal regime was an express tool for reinforcing the social hierarchy because individual rights of withdrawal were either conferred as an honour in recognition of status or involved a fee for use that linked access to economic power. Moreover, the right of management offered an avenue for élites and emperors to express their power by building and repairing aqueducts.

The continuities across different types of water rights arose from legal practice and imperial policy, when ‘policy’ is understood more as working principles than planning. Legal conservatism influenced the work of the jurists on water rights; that is, they re-used legal institutions, adapting them to new situations rather than creating new ones. The interdicts are the clearest evidence for such conservatism, as they first applied to public water and were later expanded to cover private water as well. The landowner's rights to water was also a model for other configurations of water rights, first for servitudes and then for rights of use in public water, which were treated like servitudes, as is most clearly illustrated by the treatment of water in the provinces.