INTRODUCTION

The necessity to develop and subsequently utilise caring and compassionate behaviour within the healthcare workforce is central to radiographers’ professional policy and practice 1 and in the United Kingdom (UK) is congruent with the core values of the National Health Service (NHS) Constitution. 2 Increases in patient complaints authenticated by Care Quality Commission reports of substandard care have raised concerns of malpractices, poor care and neglect. Compassion is a key recommendation of health legislation, 3 – 6 further amplified following a number of high-profile incidents in the UK where inadequate care and compassion reduced the quality of life of patients, with some instances resulting in death. 7 – 11 Numerous recommendations were formulated following these transgressions, the most pertinent being that the NHS needs to put the patient first, ensuring that they receive services from caring, compassionate and committed staff. 7

The NHS has been criticised for promoting a culture among its staff which is more focussed on doing the system’s business rather than the patients in its care. 7 Tackling this compassion deficit has been placed at the centre of government initiatives. 3 , 6 , 7 , 12 – 14 Despite reactive policy there continues to be a surfeit of failings which are all too often considered to be the inevitable.Reference Traynor 15 This continuance raises questions regarding the ability of NHS trusts, service delivery managers and individual employees to understand, interpret and implement policy recommendations regarding compassionate practice at a local level. Thus, subsequently hindering their ability to design and develop infrastructures that support the implementation of policy.

The policies themselves provide limited definition and explanation of compassion and its meaning, leading some to consider whether the complex construct of compassion is fully understoodReference Crawford, Gilbert, Gilbert, Gale and Harvey 16 , Reference Bleiker, Knapp, Hopkins and Johnston 17 and, if not, can it therefore be successfully promoted in practice.Reference Dewar 18 – Reference Dewar 21 Concepts, such as ‘compassion,’ are subjective, and are traditionally argued to be shaped and influenced by the environment and the objects in which they are situated.Reference Cronin, Ryan and Coughlan 22 Exploration and a contextual understanding was sought to refine the ambiguous, vague and often over-used term compassion in healthcare.

METHODS

Walker and Avant’s modelReference Walker and Avant 23 was used as the framework for this concept analysis. Their eight-step process (Table 1) was modified and simplified from Wilson’sReference Wilson 24 original model and provides a more pragmatic and procedural format than other models which often place more emphasis on the philosophical and conceptual approaches.Reference Carper 25 , Reference Chinn and Kramer 26 This pragmatic approach was favoured as the work focusses on healthcare within a physical environment and therefore requires understanding of the practical components of compassion. Analysis of the literature provides understanding of the defining attributes of the concept,Reference Walker and Avant 23 allowing for the synthesis of existing views, enabling it to be distinguished from other similar and associated concepts thus resolving gaps or inconsistencies in the knowledge base of the discipline.Reference Knafl and Deatrick 27

Table 1 Eight steps of Walker and Avant’s concept analysisReference Walker and Avant 23

Note:

a Borderline case not included within this article.

Data collection utilised a number of resources (Table 2).

Table 2 Resource categories used in concept analysis

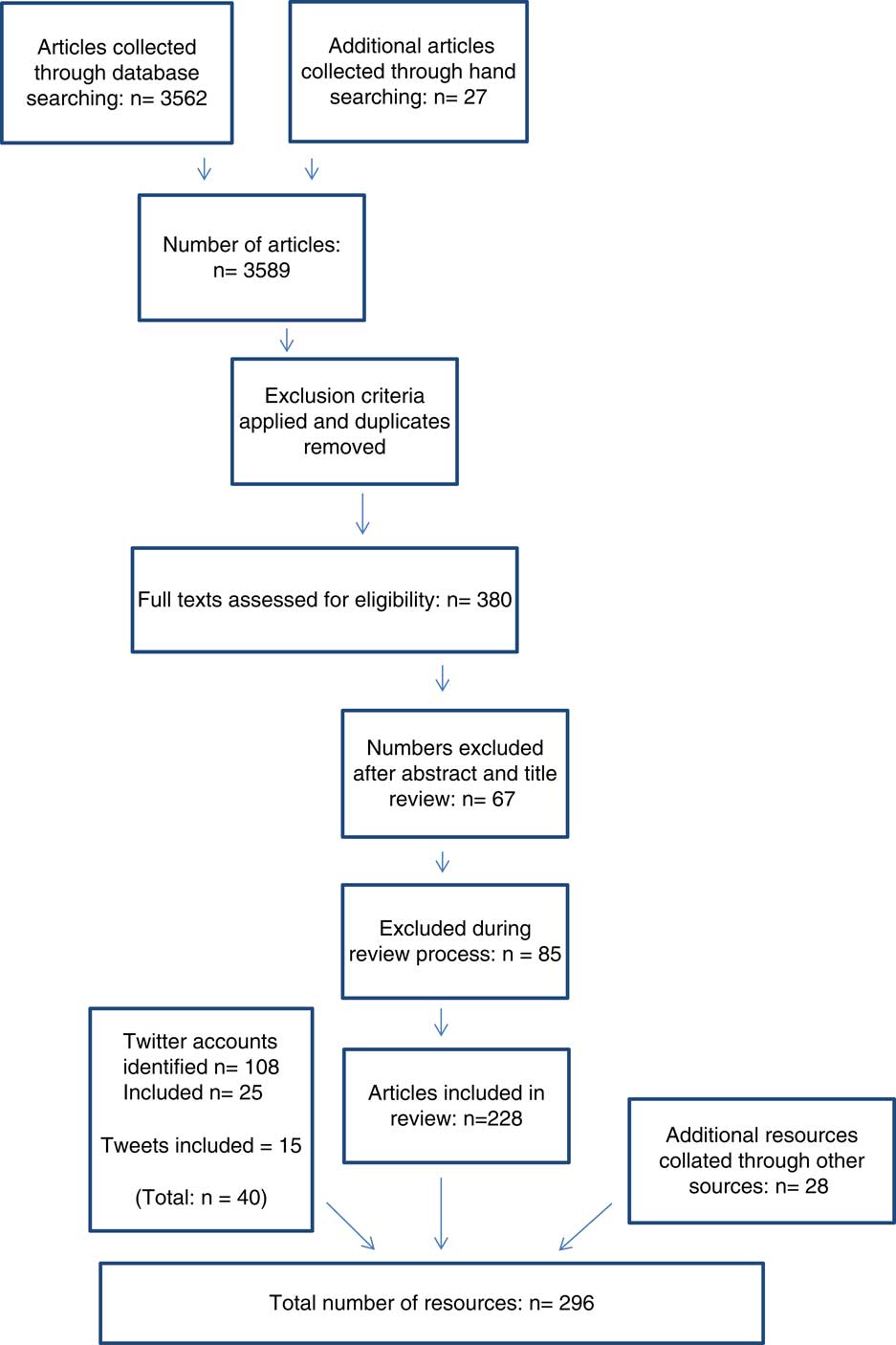

The databases were searched from October 2015 to June 2016 using a comprehensive search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to ensure only papers relevant to healthcare and with a focus on compassion were included (Appendix). The Twitter search used #compassion to capture current discussion over an 11-day period, providing a broader meaning to the term outside the published healthcare context by collating accounts and posts from individuals, newspapers, charities and organisations. Figure 1 displays the stages of the review process.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of review process.

Relevant results from each literature source category were strategically examined; key points were documented, collated and compared across the categories allowing for the development of key themes and generation of a thematic map. The author produced a Wordle (Figure 2) documenting keywords and phrases used in conjunction with the concept of compassion. This contributed to the development of behaviours and attributes associated with compassion, forming the basis of the antecedents. Saturation was reached once the literature sources generated no new themes.

Figure 2 Wordle denoting key terms from the literature associated with compassion.

FINDINGS

Step 1: concept

Compassion in healthcare.

Step 2: purpose of the analysis

To understand what compassion is and how it is displayed within a healthcare context by health professionals.

Step 3: uses of the concept

In all, 11 terms about the concept of compassion were identified within the literature; six of them were included to form this concept analysis, being considered by the authors to reflect accepted use of the concept within healthcare: compassion, compassionate, compassionate care, compassion satisfaction, compassionate practice and compassionate caring. The other five terms were excluded from this concept analysis. Compassion fatigue and self-compassion (inner compassion) are heavily discussed in relation to compassion and compassionate care, but their focus is on the self rather than towards another. The terms compassionate love, compassionate leave and compassionate use, although possessing a focus on another rather than the self, represent the love of a partner or spouse, a policy of authorised leave from work or the prescription of non-licensed drugs, respectively.

Step 4: defining attributes

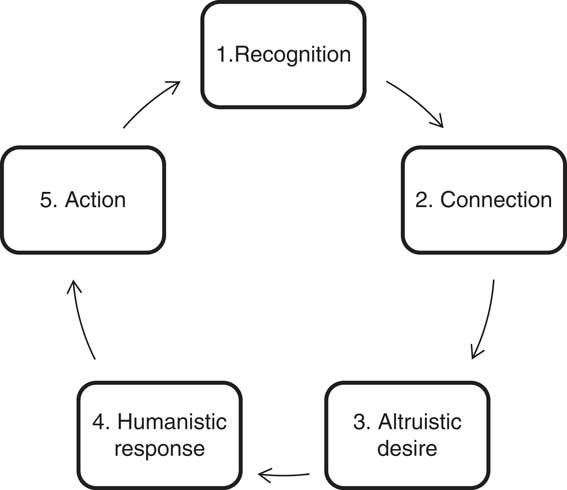

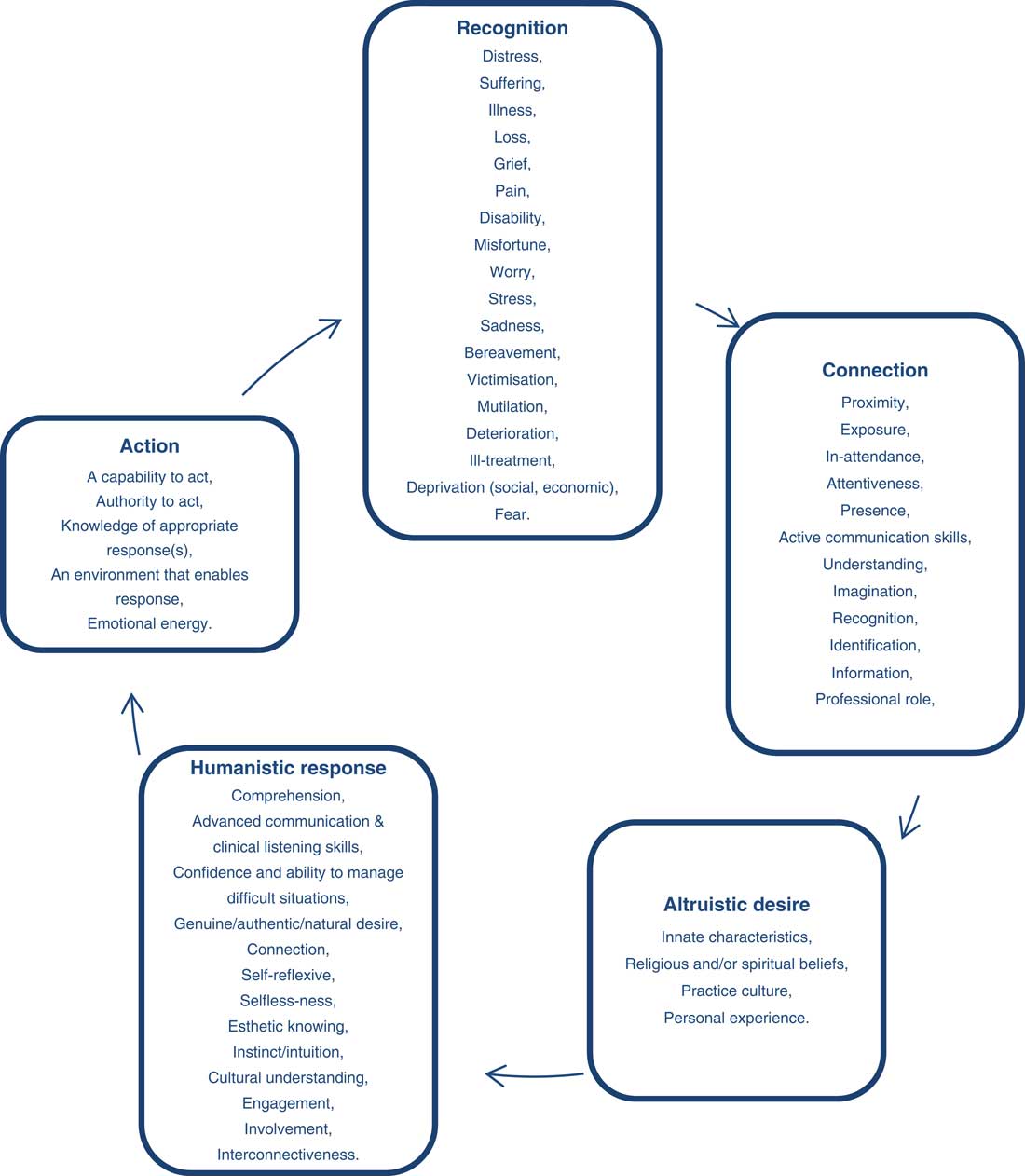

The literature examined identified compassion in healthcare as comprising of five defining attributes (Figure 3 and Table 3). Although these occur sequentially and each attribute needs to occur, the individual who is to display compassion may need to move between the attributes depending on the situation.

Figure 3 Five sequential attributes of compassion and compassionate response.

Table 3 Defining attributes of compassion

Step 5: model case

Kate was deteriorating; she had been diagnosed with advanced cancer and had been admitted to hospital, very ill with a serious infection.

Kate was distressed and felt very poorly. The nurse who was looking after her could see (1) how vulnerable and frightened Kate was, so he gently placed his hand on her arm, knelt down beside her bed (2) and said to Kate we’re going to look after you (3). Kate relayed her experiences to her friends and followers on Twitter, tweeting about a number of similar events over the course of her stay as an in-patient. She recalled her nurse ran her bath it was a hot, deep, bubbly bath, just the way she liked it (4, 5). On another evening she mentioned to the nurse that she had been struggling to sleep to which the nurse had replied don’t sit awake in the night, just buzz me and I’ll come and sit with you until you fall back to sleep (4, 5).

Step 6: additional cases

Related case

Clive, a therapy radiographer for 20 years, was chatting with a 19-year-old patient called John who was about to start radical radiotherapy for testicular cancer. John was telling him that he’d already had the tumour and his left testicle removed and how he’d had to make the difficult decision as to whether to have his sperm frozen or not before he started radiotherapy. John told Clive that it has sparked him and his girlfriend to think about their futures together and decided to get married. He confessed he was worried and kept on stressing over whether the sperm banking process may not have worked and that he was worried how his fiancé would take the news if this was the case. Clive sat and listened to the young man’s fears, ensuring that he knew he was there for him to talk to (2). Clive fully understood how John was feeling (1), not only had he treated many patients like John over his professional career, but when he was 22 he had received the same diagnosis so knew what John must have been going through.

Contrary case

Frank was attending his weekly review with the specialist radiographer; he had a review every week as part of his radiotherapy treatment for prostate cancer. He’d been worried for some time about problems he was experiencing with his erection and had wanted to ask someone for a while but he had felt too embarrassed. His wife had told him that he must speak to someone at his next appointment as it was becoming a problem for them as a couple. Towards the end of his review the radiographer asked him if there was anything else she could help him with. Frank told her about the problems he and his wife were experiencing when they tried to have intercourse, to which she replied it’s just an effect of his diagnosis and the radiotherapy treatment. Frank expressed that he knew this but his original consultant had said there were some options and maybe some medication he could take. Reluctantly the radiographer nodded and replied this wasn’t her area and so would go and ask a colleague for some advice. The radiographer exited the room into the main waiting area; leaving Frank sat alone with the door open. Whilst Frank was waiting he could hear laughter, listening in he heard his specialist radiographer saying, (laughing)…I know tell me about it and it his age it…(laughter), yeh good point I’ll tell him to google it there be plenty of stuff on the Internet for that kind of thing…well yeh, I suppose whatever floats your boat (laughter).

Step 7: antecedents and consequences

Figure 4 identifies antecedents for each of the five attributes of compassion identified in Figure 2.

Figure 4 Compassion’s defining attributes and their antecedents.

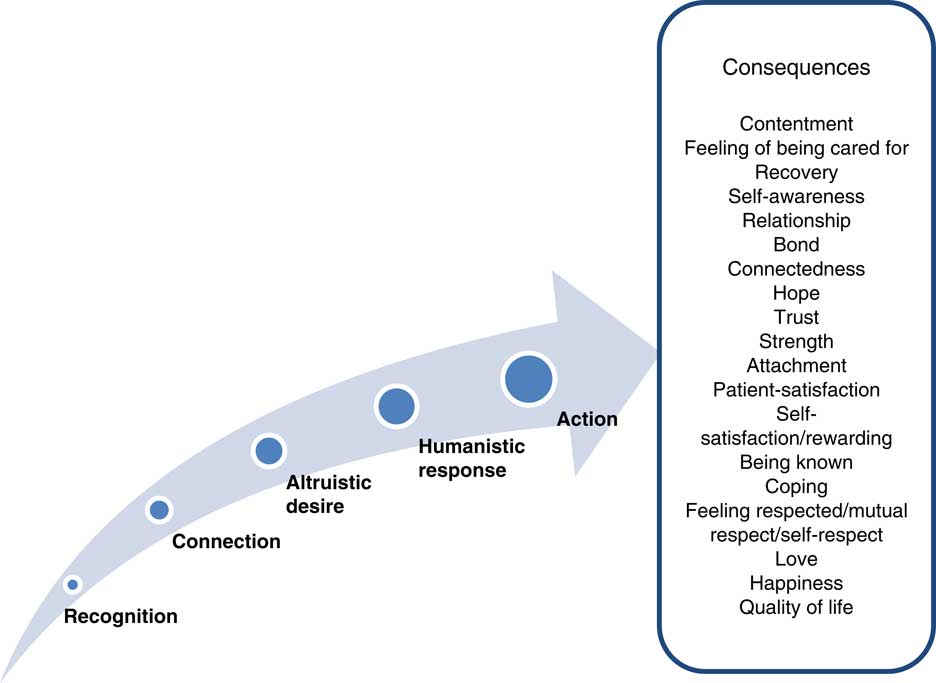

Figure 5 details the consequences which transpire when the five components (defining attributes) of compassion occur.

Figure 5 Consequences of the five components (defining attributes) of compassion.

Step 8: empirical referents

The concept analysis ascertains that the empirical referents of compassion can be structured into three categories: non-verbal, verbal and professional practice.

Non-verbal display

Compassionate behaviours included eye contact,Reference Saunders 28 engaged body language,Reference Marchuck 29 listening with full attentionReference Van Der Cingel 30 – Reference Penson, Seiden, Chabner and Lynch 32 and facial expressions which matched the subject of conversation.Reference Priddis, Schmied, Kettle, Sneddon and Dahlen 33 All of these were deemed to display commitment and devotion by the health professional to what was being said, the significance of the topic and therefore demonstrated they were vested in them.Reference Marcum 34 , Reference Bynum 35

Verbal display

Compassionate behaviours included being provided with clear, non-jargon, individual patient-tailored information, being given time and the opportunity to ask questions, not being spoken over, the professionals asking questions of them about their preferences and level of understanding.Reference Priddis, Schmied, Kettle, Sneddon and Dahlen 33 , Reference Bynum 35 – Reference Steele, Kaal, Thompson, Barrera, Compas, Davies, Fairclough, Foster, Jo Gilmer, Hogan, Vannatta and Gerhard 43 The tone of voice and the language used was of particular importance in a professional’s ability to portray compassion due to the effects of an imbalance of power between the health professional and the patient.Reference Penson, Seiden, Chabner and Lynch 32 , 44 Belittling, judgemental attitude, oversimplifying and not taking the patient seriously were all perceived as uncompassionate behaviours.Reference Smith, Ho, Langston, Mankani, Shivshanker and Perera 45 , Reference Santen and Hemphill 46

Cutting across both verbal and non-verbal display was a display of warmth through touch, tone of voice and body language. Warmth made patients feel comfortable and gave the feeling of being ‘cared for’ even if the health professional was not actively involved in their treatment.Reference Horsburgh and Ross 38 , Reference Goetz, Keltner and Simon-Thomas 47 Also underlying throughout was a desire for the health professional to show respect to the patient.Reference Rohan and Bausch 48 Patients wanted to feel like their opinions, beliefs and preferences were not only known but valued by those responsible for their care.Reference Marchuck 29 , Reference Proctor 31 , Reference Thorne, Kuo, Armstrong, McPherson, Harris and Hislop 37 , Reference Santen and Hemphill 46 , Reference Goetz, Keltner and Simon-Thomas 47 , Reference Schapira, Lawrence, Blaszkowsky, Cashavelly, Kim, Riley, Wold, Ryan and Penson 49 Patients wanted interactions in all formats to be non-judgemental and be both understanding and accepting of the circumstances surrounding their needs.Reference Puchalski and Jafari 50

Professional practice

Compassionate behaviours included undertaking and completing any required standard tasks as part of the patient’s pathway and treatment,Reference Steele, Kaal, Thompson, Barrera, Compas, Davies, Fairclough, Foster, Jo Gilmer, Hogan, Vannatta and Gerhard 43 because ensuring that all process components have been completed before appointments prevents the patient facing additional distress of waiting, worrying about delays and being fearful of the consequences such delays could have on their prognosis. Patients want the health professionals to understand and appreciate the impact their current issue (diagnosis, bereavement, treatment, etc.) is having on the physical, emotional and social rudiments of their life.Reference Van Der Cingel 30 , Reference Proctor 31 , Reference Priddis, Schmied, Kettle, Sneddon and Dahlen 33 , Reference Mannix 51 , Reference Straughair 52

Furthermore, the practice of elementary tasks is deemed to be compassionate when delivered in such a way where a patient’s dignity is maintained and considered as paramount.Reference Proctor 31 , Reference Horsburgh and Ross 38

One of the five defining attributes of compassion was a personal connection between the two parties.Reference Thorne, Kuo, Armstrong, McPherson, Harris and Hislop 37 , 44 , Reference Price 53 , Reference Bolderston, Lewis and Chai 54 Often this is on the basis of shared experience, knowledge or understanding of the current situation. There are caveats however within this, as some level of professional boundary is required in order for health professionals to make balanced, informed decisions about the care they provide which are not based on previous emotive events, beliefs or feelings.Reference Schapira, Lawrence, Blaszkowsky, Cashavelly, Kim, Riley, Wold, Ryan and Penson 49

Limitations

Despite the implementation of a rigorous search and review strategy, consideration needs to be given to omission of possible resources which may have limited the rigour of the findings. However, a saturation of themes occurred across all of resource categories denoting that further resources would not have brought additional themes to the analysis.

Furthermore, it may be argued that the use of Twitter did not align with the original aim to review compassion within a healthcare context. Twitter however provided a broader meaning to the term outside the published healthcare context as the twitter hashtag collated accounts and posts from a wide range of individuals, newspapers, charities and organisations. Both Twitter and the dictionary definitions underpinned the review, clarified compassion outside of the healthcare environment by identifying patterns of useReference Cronin, Ryan and Coughlan 22 and as such provided a boundary for understanding the differences between the concepts of compassion when used in different environments.

Previous concept analyses have focussed on different uses of the topic which do not denote the practice or presentation of compassion within healthcare, for example compassion fatigueReference Coetzee and Klopper 55 and self-compassion.Reference Reyes 56 Where compassion has been the focus of the analysis, defining attributes have failed to be identified.Reference Schantz 57 Classification of these not only enables the concept to be distinguished from other similar concepts,Reference Walker and Avant 23 but by inclusion provides a model to identify if each of the five attributes of compassion is being displayed. Furthermore, this work has provided defining attributes, antecedents and consequences which are derived from and relevant to healthcare practice giving real world contextual meaning to the findings. Understanding and defining compassion is not just of relevance or only applicable to UK practice, the findings of this concept analysis did not focus purely on one specific discipline as reported in other cases.Reference Menage, Bailey, Lees and Coad 58 Therefore, findings will be transferable to all health professions where treatment and patient-centred care is an essential requirement of the role.

CONCLUSION

Employment of a concept analysis has distinguished compassion in healthcare from other contexts and identifies it as composed of five attributes: Recognition, Connection, Altruistic desire, Humanistic response and Action. Associated meanings and behaviours have been outlined aiding an understanding of compassion. The findings however identify the complexity of the term and subjective nature in which it is displayed and in turn perceived.

The literature utilised within this process has identified that there is no one agreed definition of compassion. Those which have been developed have been given an assigned meaning based on previous literature and dictionary definitions as opposed to being developed within an appropriate healthcare context. Further research needs to be conducted based upon these findings to develop a healthcare explicit definition of compassion within healthcare which will enhance understanding, thus facilitating active engagement and implementation into practice.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

APPENDIX: SEARCH STRATEGY

An initial scoping search identified a number of fundamental papers whose keywords have been used to develop search terms in conjunction with database-specific indexed control vocabulary (including MeSH terms).

A building block approach as advocated by Booth (2008) provided a foundation to the search with the numerous facets connected or eliminated by the use of Boolean operators.

Truncations were used to widen the search, for example, compassion* retrieved compassion and compassionate. Similarly, wildcards allowed for variances in spelling of common words, for example behavio#r or behavio?r.

Key terms

compassion*, ‘compassion* car*’.

‘Professional behav*’, ‘practitioner-patient relation*’, ‘nurse-patient relation*’, ‘patient car*’, ‘person-centred car*’, ‘professional-patient relation*’, ‘relational practice’, ‘staff-client relation*’, ‘relationship-centred car*’, ‘professional issues’, ‘patient-centred car*’.

AND

healthcare, ‘health profession*’, medic*, ‘clinical medic*’, ‘Medical car*’, ‘nurs* practice’, ‘allied health profession*’, ‘multidisciplinary team’, hospital*, ‘professional carer*’, ‘health service*’, ‘healthcare organisation’, ‘health person*’.

AND

Behav*, behavio#r, attribute*, trait*, relation*, attitude*.

Inclusion criteria

Resources which

-

∙ were written in English

-

∙ published between 1995 and 2015

-

∙ reviewed compassion and its concepts within healthcare

-

∙ discussed and/or examined compassionate behaviour in healthcare.

NB: Evidence-based material was not exclusively searched as the concept of compassion is fluid and open to individual interpretation. The literature review therefore wanted to capture this discussion and as such included non-research-based material including discussion papers, commentaries, letters to editors, book chapters, etc. These provided background and rationale for the project in addition to helping to understand what is meant by compassion in healthcare.

Exclusion criteria

Resources which

-

∙ reviewed compassion outside of healthcare practice

-

∙ addressed self-compassion

-

∙ investigated/reported approaches to reduce compassion fatigue

-

∙ solely addressed the management of patients receiving end of life/palliative medicine

-

∙ related to professional practice issues outside of compassion, for example, medical errors which are not due to poor compassionate care

-

∙ addressed other behaviours, for example, medical skill levels which are not attributable to compassion.

Google and Google Scholar were used as method of searching grey literature and as a supplementary tool in conjunction with reference searching from seminal papers, respectively.

Reference

Booth A. Using evidence in practice. Unpacking your literature search toolbox: on search styles and tactics. Health Info Libr J 2008; 25: 313–317.