How do White Americans evaluate the politics of belonging in the United States across different ethnoreligious identity categories? Research suggests Americans are more accepting of immigrants with higher levels of education, White-collar jobs, and English proficiency (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2019; Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Hainmueller, and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015). The literature describes these characteristics as signaling how much immigrants might contribute to the economy and how easily they can assimilate into American culture, each a constitutive part of belonging. Some of this work has also found that the country of origin of the immigrant influence these decisions, as well. For instance, certain groups, such as Asian and Latin Americans, are evaluated as foreigners even if they have lived in the country for generations (Chouhoud, Reference Chouhoud and Stockemer2022; Huynh et al. Reference Huynh, Devos and Smalarz2011; C. J. Kim Reference Kim1999; S. Y. Kim et al. Reference Kim, Wang, Deng, Alvarez and Li2011). In this case, country of origin is a salient identity characteristic that precludes the group from full inclusion. This exemplifies how certain racial groups may not be evaluated as belonging in the United States, even if they embody qualities such as English proficiency or high education merely due to their racial background. While country of origin is usually a marker of insider or outsider status as well as one’s race/ethnicity, recent research suggests that religion plays a role in how society perceives and assigns racial categories to others (d’Urso Reference d’Urso2022).Footnote 1 This means religion may also play a role in how people decide who belongs in the United States. Given that religion and race can be conflated, how do Americans navigate between these two identity characteristics when expressing who belongs in the United States?

In the case of Muslims and Middle Easterners and North Africans (MENA) individuals, religion and race are often conflated (Beydoun Reference Beydoun2013; Husain Reference Husain2019; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Peek Reference Peek2005). This complexifies our understanding of the formation of attitudes toward migrants (Allport Reference Allport1954; Arora Reference Arora2020; Hellwig, and Sinno Reference Hellwig and Sinno2017; Reny, and Barreto Reference Reny and Barreto2022), the racialization of different migrant groups (Romero Reference Romero2008; Sáenz, and Manges Douglas Reference Sáenz and Manges Douglas2015; Tesler Reference Tesler2018; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013), and perceptions of belonging in the United States (Chouhoud Reference Chouhoud and Stockemer2022; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Lajevardi and Sohlberg2022; Hobbs, and Lajevardi Reference Hobbs and Lajevardi2019; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020). For instance, White Americans are less likely to accept certain Muslims (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2019; Chouhoud Reference Chouhoud and Stockemer2022) and certain Middle Easterners (Hainmueller, and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015) into the United States. Given that MENA and Muslim identities are often described interchangeably, it is not clear what drives these existing findings: religion (i.e., presumed Muslimness of a given MENA immigrant) or race/ethniciy (i.e., presumed MENA identity of a given Muslim immigrant).

We compare two hypotheses to understand the relationship between religion and race (proxied through country of origin) on belonging. Our first hypothesis is that religion, specifically Muslim identity, has been racialized to the point where actual race/ethnicity will be an irrelevant identity characteristic for those who belong in the United States. That is, regardless of an individual’s race, a Muslim identity will be the most salient identity factor White Americans will use to evaluate who belongs. We contrast this approach to the idea that MENA-Muslim identity is understood intersectionally: while MENA and Muslim identities can overlap, one can be MENA and not Muslim or Muslim and not MENA. In practice, however, because individuals often use the terms MENA and Muslim interchangeably, the two identities may not be understood as distinct identity facets but instead conflated into one trait that transcends either category of Muslim or MENA. Thus, White Americans may discriminate more against an individual who fits the prototype of a MENA-Muslim immigrant.

We examine these questions while using a conjoint survey experiment that allows us to create more holistic profiles of migrants and specify religion and race (proxied via country of origin). The experimental design fielded through Bovitz, Inc., isolates the role of both country of origin and religion on who White Americans indicate belongs in the United States—both via green card and assimilation. With this measurement strategy, we investigate how the public conceptualizes Muslim migrants of different origins, in contrast to MENA individuals with other religions. We find White Americans singularly consider religion when determining who should be given a green card. However, they do consider religion and race when determining who will better assimilate into the United States.

The questions at the heart of this paper, then, examine the nature of MENA as an ethnoracial categorization: a demographic marker that incorporates elements of both race and ethnicity. MENA individuals come from a specific geographic area, can be Muslim, but are not exclusively, and may be of various races. While MENA and Muslim identities may overlap and often be conflated with each other among outsiders, one key effort in this paper is to recognize that research must understand the extent to which the public understands these overlapping identities. Thus, a major contribution of this effort is to consider how ethnoracial identities are understood by outsiders.

The results also have important policy implications. First, the results present further evidence for reconsidering a MENA categorization on the census, as MENA individuals are indeed viewed differently than White (the current legal classification in the United States), which is consistent with other research (d’Urso Reference d’Urso2022). While these definitions are important for how migrants are viewed, they are also important in determining how to present questions on the U.S. Census, and if the traditional question choices are the most appropriate (Jones Reference Jones2017). These findings join that of prior work (Beydoun Reference Beydoun2015a, Reference Beydoun2015b; Jonny Reference Jonny2020; Kayyali Reference Kayyali2013; Mathews et al. Reference Mathews, Phelan, Jones, Konya, Marks, Pratt, Coombs and Bentley2017; Strmic-Pawl et al. Reference Strmic-Pawl, Jackson and Garner2018) as evidence that including MENA as a separate category most accurately describes the experience of MENA individuals in the United States—regardless or religious background.

With practical application to immigration policy, this research gives insight into how White Americans may react to policies that support including immigrants—regardless of their education, English fluency, or race—simply because they are Muslim. But in a broader sense, it elucidates the immense burdens Muslim Americans may face when trying to belong in and assimilate into the United States. This can have downstream consequences for how the functioning of a pluralistic democracy when groups who otherwise legally belong are not treated as such. We add nuance to the literature on immigration and belonging by showing that race or religion alone is not enough for understanding societal perceptions of who belongs. In fact, removing religion from consideration prevents us from understanding the marginalization of those who may be racially White but excluded from joining America due to Muslim identity. At the same time, focusing on Muslim identity, alone, precludes us from understanding how anti-Islamic attitudes toward those already in the United States are not uniformly distributed across Muslim racial identity groups.

How religion and race contribute to belonging

Social belonging revolves around who society at large accepts and believes belongs in a given country.Footnote 2 Deeply tied to an understanding of what belonging means are beliefs related to if and how well migrant communities will assimilate into a new country (Bonilla, and Mo Reference Bonilla and Mo2018). These attitudes tend to rest on assessments of cultural or religious assimilation, such as whether migrants will “threaten” national traditions (Brader et al. Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Fetzer Reference Fetzer2000; Kinder, and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2010; Knoll et al. Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011).Footnote 3 For Muslim and MENA individuals, understanding belonging in terms of cultural assimilation is of particular importance because a key element of belonging incorporates religion as a feature potentially preventing assimilation. This paper examines assessments of belonging but does so using two competing theories for the interplay between race and religion on social belonging in the United States. First, we examine literature suggesting Muslim identity, alone, is the most salient identity characteristic when considering who belongs in the United States. We compare this with the literature on intersectionality. MENA and Muslim identities are understood so interchangeably that it has transcended either category and is an identity in and of themselves. Thus, White Americans may only preclude MENA-Muslim immigrants from social belonging.

The salience of Muslim identity

Anti-Muslim attitudes and policies did not exclusively emerge out of 9/11, though much work has discussed changes in anti-Muslim attitudes post-9/11 (Bonilla et al. Reference Bonilla, Filindra and Lajevardi2022; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Naber Reference Naber2000). For instance, Kalkan et al. (Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009) find Americans view Muslims negatively because they are seen as a cultural outgroup. Although tolerance toward other religious and racial outgroups is positively correlated with positivity toward Muslims, perceptions of Muslims as cultural outsiders are negatively correlated with attitudes toward Muslims. Moreover, when comparing levels of xenophobia (i.e., fear, hatred, or prejudice against those from another country) versus Islamophobia (i.e., fear, hatred, or prejudice against Islam and Muslims), researchers find respondents have a stronger negative effect on Muslim foreigners than toward (non-Muslim) foreigners (Spruyt, and Elchardus Reference Spruyt and Elchardus2012).

Being perceived as cultural outsiders stems from the long-standing tropes of Orientalism (Said Reference Said1979). As Said argues, the Occident could only understand itself through the creation of the Orient. The Orient and by extension Muslims have been stereotyped as violent, misogynistic, intolerant, and fundamentalists (Esposito, and Kalin Reference Esposito and Kalin2011; Hobbs, and Lajevardi Reference Hobbs and Lajevardi2019; Khan, and Ecklund Reference Khan and Ecklund2012; Said Reference Said1979). Research suggests Orientalist tropes—present and prevalent long before 9/11—are key drivers in how Americans evaluate Muslims (Oskooii et al. Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2019). The aftermath of 9/11 merely made these tropes more salient and solidified in the mind of Americans (Dana et al. Reference Dana, Lajevardi, Oskooii and Walker2018). Although it may seem Orientalism is more suited as a framework for former colonial countries to understand their role in colonialism—thereby adjacent to the U.S. context—research has shown that Americans hold and employ Orientalist stereotypes when thinking about Muslims (Oskooii et al. Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2019). This means that not only was the influence of Orientalism far-reaching, but it has been long-lasting, as well. As a result, the American public has been shown to view Muslims as “culturally inferior, uncivilized, and out of touch with modern social and democratic norms” (Oskooii et al. Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2019, p. 3). These stereotypes are linked with the racialization of Muslims.

In addition to being perceived as cultural outsiders, another reason to suspect Muslim identity may be more salient for social belonging relative to race is because of the racialization of Islam. That is, Muslim identity, although one of religion, is often thought of as a racial category. Scholars have focused on the racialization of many identity groups, including the racialization of Muslims (Al-Saji Reference Al-Saji2014; Aziz Reference Aziz2022; Bayoumi Reference Bayoumi2006; Beydoun Reference Beydoun2013; Considine Reference Considine2017; Fourlas Reference Fourlas2015; Galonnier Reference Galonnier2015; Garner, and Selod Reference Garner and Selod2015; Jamal, and Sinno Reference Jamal and Sinno2009; Meer Reference Meer2013). The racialization of religion occurs when “religious beliefs and practices of the adherents are associated with cultural traits, which in turn are surrogates for biological traits” (Aziz Reference Aziz2022, p. 20). This means that Islam is no longer seen as a religious practice, protected under the First Amendment (Aziz Reference Aziz2022; Garner, and Selod Reference Garner and Selod2015; Gotanda Reference Gotanda2011, Reference Gotanda2017). Rather, religious identity is seen as an immutable trait.

Because of the racialization of Islam, Islamophobia has little to do with religious beliefs but with perceptions of those who are Muslims: “In a religious conflict, it is not who you are but what you believe that is important. Under a racist regime, there is no escape from who you are (or are perceived to be by the power elite)” (Bayoumi Reference Bayoumi2006, p. 275). Therefore, Muslim individuals’ racial background matters little when they are being evaluated; all that matters is that the individual is Muslim. Indeed, research on White American converts to Islam has found this to be true. White American Muslims are often assumed to be immigrants and often met with tropes associated with Muslims (Husain Reference Husain2019). This means that although there are many Muslims from all ethnoracial backgrounds, the process of racialization has made it difficult to disentangle religious beliefs, something that is (largelyFootnote 4 ) a choice and mutable, from an ethnoracial identity, which is immutable. Thus, we test whether Muslim identity is prioritized over other identity characteristics when determining who belongs.

H1: Muslim immigrants will be considered less likely to belong in the United States regardless of their race, holding all other features constant.

Are MENA and Muslim identities understood together?

In contrast to Muslim identity, being the most salient identity characteristic for belonging is the argument that MENA-Muslim identity could be understood intersectionally. Therefore, only those who fit into the MENA-Muslim category will be excluded, while other Muslim racial identities could viewed as belonging. As mentioned, Muslim identity is not a racial identity, yet it is regularly discussed in relation to MENA racial identity (Khan, and Ecklund, Reference Khan and Ecklund2012; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020; Nielsen, and Allen Reference Nielsen and Allen2002). For instance, when discussing “Muslims” it is often apparent the scope is specifically MENA-Muslims. This is argued to occur because individuals tend to view Muslims as monolithic (Khan, and Ecklund, Reference Khan and Ecklund2012; McCarus Reference McCarus1994; Nyang Reference Nyang1999). It is not, therefore, surprising that negative sentiments are present toward both Arabs/MENA individuals and Muslims (Kteily et al. Reference Kteily, Bruneau, Waytz and Cotterill2015). And this is by no means a new trend. For instance, polls conducted in 1991 and 1993 showed that Americans viewed Arabs as “religious fanatics” (Cainkar Reference Cainkar2009), indicating that Americans blur the lines between the racial category and religious affiliation. The blurred line between the racial and religious category is best understood through an intersectional framework.

The theory of intersectionality emphasizes the understanding of identity as being formed of multiple features, all of which occur simultaneously (Collins Reference Collins1991; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1990; Hancock Reference Hancock2016). That is, intersectionality theory is “interested in how the differential situatedness of different social agents affects the ways they affect and are affected by different social, economic and political projects” (Yuval-Davis Reference Yuval-Davis2006, p. 4). This means that people with particular combinations of features (e.g., gender and race or race and religion) may be subjected to unique lived experiences that cannot be captured by one identity or even the addition of two identities (Hancock Reference Hancock2007). Considering this framework—that White Americans commonly group MENA and Muslim as overlapping categories—means that Muslims from different racial backgrounds may be viewed differently. Thus, theories of intersectionality help explain the dynamics of power and discrimination along racial and religious lines; when evaluating who belongs are these identities evaluated together or as distinct considerations?

A Muslim religious identity then intersects with other features that are historically marginalized, “especially with respect to gender and religion (e.g., hijabi women), or race and religion (e.g., African American Muslims)” (Lajevardi (Reference Lajevardi2020, p. 11). Often “Muslim” is used to refer to anyone from the Middle Eastern or North Africa, regardless of their religion. At the same time, Muslim identity is often not thought of as, including East Asian-, Black-, or Latin Americans. As Hussain (Reference Husain2019) shows, Black and African American Muslims are often not thought of as being Muslim at all. One of her interviewees remarks: “No matter how I felt about my identity, Muslim or not, I’ve been treated like a black dude” (Husain Reference Husain2019, p. 594). This suggests that in the mind of Americans, Muslim identity feels inherently tied to the MENA race. Black-Muslims and MENA-Muslims do not have the same positionality or experiences merely because they are Muslim. Rather, the intersections of Muslim identity with MENA identity produce different life experiences for these different groups.

Recent empirical findings also lend credence to the idea that perhaps Americans understand Muslim identity incompletely, conflating it with a racial or geographic identity. Although MENA individuals are legally classified as White in the United States, White Americans do not firmly place MENA individuals into the category of Whiteness. D’Urso (Reference d’Urso2022) shows that White Americans use both country of origin and religious cues when operationalizing who is White. While these two traits additively constitute assignment as White, those who were MENA-Muslims were perceived to have darker skin pigmentation relative to those who are either Muslim and White, MENA and Christian, or both Christian and White. This suggests Muslim MENA identity could be understood best from a perspective of intersectionality, because the two identities together are perceived as a part of the cultural stereotype of darker-skinned individuals, than any one trait on its own.

One drawback of this study is, however, that there is no assessment of the consequence of this identity. That is, although White Americans may not use religion alone as a proxy to assign racial categories to others, do they still evaluate Muslims differentially based on ethnoracial background? Perhaps negative sentiment toward Muslims is directed toward the prototype of a MENA-Muslim, rather than any Muslim. Race and religion, together, may play a role in determining who belongings, in addition to religion; thus, only MENA-Muslims would be precluded from belonging.

H2: Muslim immigrants from the Middle East or North Africa will be thought to belong in the United States less than Muslim immigrants from other parts of the world, holding all other features constant.

Design and method

Experiments using conjoint designs have become more prevalent within political science (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015; Hainmueller, and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Horiuchi et al. Reference Horiuchi, Markovich and Yamamoto2022). Similar to a full factorial design, conjoint experiments allow scholars to understand multidimensional preferences people have when making choices based on hypothetical profiles. A conjoint design allows for more attributes to be compared without having traditional issues of power in full factorial designs.Footnote 5 In this case, a conjoint design is an appropriate design, because we are interested in understanding the multidimensional preferences of immigrant belonging. The study and our hypotheses were preregistered.Footnote 6 With our design, we had sufficient power to detect effect sizes as small as 0.05% changes with 86% power and 95% confidence intervals (Lukac, and Stefanelli Reference Lukac and Stefanelli2020). Appendix 3 provides our power calculation.

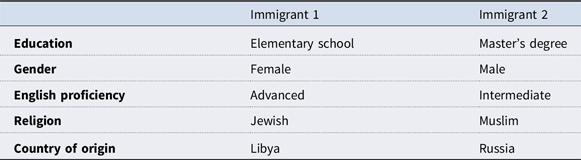

In this study, White respondents were given two immigrant profiles with several descriptive attributes. Each profile contained five attributes: education, gender, English proficiency, religion, and country of origin.Footnote 7 Table 1 lists the attributes on which each immigrant profile varies. Education, gender, and English proficiency are all attributes shown to affect attitudes toward migrantsFootnote 8 and are included to both ground the experiment in what might be considered relevant considerations and work as a check of internal validity, as well. Education (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Hainmueller, and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Scheve, and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001) as well as “American identity”—of which English proficiency is a key feature—are both relevant characteristics with well-known responses (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2010; Wong Reference Wong2010; Wright, and Citrin Reference Wright and Citrin2011). Thus, our expectation, consistent with prior literature, is that education attributes and English proficiency with the expectation that higher levels of education and increased English fluency will be viewed more positively.

Table 1. Attributes and levels

*Implied attribute based on country of origin, not explicitly asked.

The attributes that test our hypotheses are the religion and country of origin attributes. Elements for the religion category include the three Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. With the country-of-origin attribute, we create a proxy for race by signaling the region a migrant is from. We selected multiple countries of origin per region, as specific countries of origin have been shown to influence the acceptance of immigrants (Brader et al. Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Citrin et al. Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997). Bosnia and Russia are Eastern Europe, Lebanon, Iran, and Libya are the Middle East and North Africa, Sudan is Black, and India and Pakistan are South Asia.Footnote 9 The four regions also work to proxy race/ethnicity: Bosnian and Russians are Eastern European and White; Lebanese, Iranians, and Libyans are MENA; Sudanese are Black; and Indians and Pakistanis are South Asian. The treatment bundles race and country of origin as a proxy, but we argue this is the strongest approach for our study. First, White Americans use country of origin to assess race/ethnicity (d’Urso Reference d’Urso2022). Second, signaling race with an image, for example, presents additional challenges with the study of an ethnoracial categorization such as MENA and Muslim because cultural or religious garments signal more than simply stating the religion or race/ethnicity alone. For instance, the choice to wear a head covering by women is both regional and religious, and the design of the head covering differs by both region and culture (see Monkebayeva et al. Reference Monkebayeva, Baitenova and Mustafayevа2012). Third, White Americans appear to readily connect a country of origin with a racial background. Two supplementary studies presented in Appendix 1 demonstrate that White Americans assign racial categories via country of origin that is consistent with a country or origin proxy for race. That is, respondents grouped the eight countries of origin into the four abovementioned racial groups: White, MENA, Black, and South Asian. Finally, our country selection process balanced additional country information as much as possible.

While the country-of-origin proxy may signal more information because international relations between the United States and each country are not the same, we also held constant the envisioned country-of-origin for each respondent by describing a country of origin. We selected countries based on the known populations of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim immigrants of which most respondents should be aware. For each region, we also chose one country with a positive or neutral relationship with the United States, and another with a negative or contentious relationship with the United States. For example, although Bosnians and Russians are both considered racially White, the United States has a tense relationship with Russia, relative to Bosnia. The same is for Pakistan relative to India. As a result, we controlled for country of origin while also recognizing potential variation in evaluations that may be due to how well-liked or disliked individuals from a given country may be. After fielding, we also did not find evidence of within-region differences for country of origin as demonstrated in Appendix 5.

Table 2 provides an example of what respondents saw when given the immigrant profiles. Respondents were assigned a pair of immigrant profiles, with a full factorial design. After looking at both profiles, respondents were asked two questions which became our dependent variables. First, respondents were asked to select to which immigrant they thought the United States should give a green card. Although there are many types of visas, they are all temporary to varying degrees. Green cards, on the other hand, are more permanent and allow for a pathway to naturalization, and we believe this better captures our aim of understanding which characteristics White Americans value for belonging. Second, respondents were asked how likely the immigrant is to assimilate into U.S. culture. While the first DV is a forced choice, the second is a Likert scale asked for each immigrant profile shown. Respondents repeated this task four times so that they saw five-paired profiles with subsequent questions.

Table 2. Example of immigrant profiles given during conjoint task

The respondent i chooses among immigrant profiles k in task j. This function is modeled as a vector containing the attributes of the immigrant profiles presented to the respondent for each task. Because each respondent provides us with j × k observations, we use respondent cluster robust standard errors. With two profiles over five iterations, each respondent provides 10 rows of observations. Each row represents one profile as well as the attributes that the respondent was exposed to for that profile.Footnote 10

Analyses of conjoint designs allow us to consider multidimensional preference. We are interested in the marginal means of attributes of immigrants on belonging. We report marginal means instead of the Average Marginal Component Effect (AMCE) because the marginal means are the “level of favorability toward profiles that have a particular feature level, ignoring all other features” (Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020, p. 209). For instance, in a force choice design, the marginal mean corresponds directly to the probability a given attribute level is selected. We have also included the AMCE figures of our main findings in Appendix 4 and tables of the AMCEs and robustness check in Appendix 8.

Data and findings

This study was conducted on Qualtrics and fielded to 600 White, non-Latinx respondents by a quota-based sample from Bovitz, Inc Forthright panel from August 12 2019 to August 24 2019.Footnote 11 Demographic characteristics of the sample are available in Appendix 2. Our findings support prior literature on evaluations of immigrants. More educated immigrants, with more English fluency, and are women, are more likely to be selected to belong in the United States. Moreover, we find support for hypothesis 1 and partial elucidation of how the intersectionality of race and religion influences belonging. That is, regardless of race (proxied by country of origin), White Americans are more likely to exclude immigrants from the United States who are Muslim. Respondents also tend to exclude based on religion beyond race: if an immigrant is both White and Muslim, White respondents are more likely to exclude them. However, we find that although White Americans believe all Muslims are less likely to assimilate into American culture, on average, Muslim MENA immigrants are rated the lowest.

As described above, we present the results using country of origin as a proxy for race. We feel comfortable using this proxy for two reasons. First, two manipulation checks that show respondents tend to infer the proxied races from these countries (discussed further in Appendix 1, Studies 1 and 2). Second, geopolitical information does not seem to affect the results. While our intent with the treatment was to balance U.S. relations within region, we also find no statistical difference between the two countries in each region. Analysis of the results by country can be found in Appendix 5.

Figure 1 displays the main effects of the experiment, with the features—grouped by attribute—displayed on the y-axis and the x-axis displaying the marginal means (tables of the marginal means are provided in Appendix 6). This figure shows the attributes associated with respondents selecting or avoiding a given immigrant profile for a green card. In this image, the features are centered around 0.5 because the question was a forced choice: selecting either Immigrant 1 or Immigrant 2 to receive a green card. Attributes that do not overlap with 0.5 indicates that the attribute was selected or avoided at a rate that statistically significantly differs from random. We can also compare within attributes to see which characteristics, or levels, were preferred.

Figure 1. Who Should be given a Green Card?

Note: Figure 1 contains the marginal means for each group. The bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Immigrants with higher education and English fluency who are female, Jewish, Christian, White, or South Asian are more likely to be selected. Less educated, men, with less fluency, and immigrants who are Muslim, Middle Eastern, or Black are less likely to be selected.

First, profiles with higher levels of English proficiency, higher levels of education, and women cause a more positive response among respondents. Further, each subsequent degree is preferred relative to the degree below it at statistically significant levels. These results are consistent with prior literature and gives us confidence in the external validity of the treatment. Relative to elementary education alone, those with master’s degrees were 38.1 percentage points more likely to be selected (p<0.01). Those with college (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.57, p<0.01) and high school (

$\bar x$

= 0.57, p<0.01) and high school (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.42, p<0.01) were also more likely to be selected relative to those with only elementary education (

$\bar x$

= 0.42, p<0.01) were also more likely to be selected relative to those with only elementary education (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.31. Relative to male immigrants, female immigrants were 6.5 percentage points (p<0.01) likely to be selected. Moreover, those who had fluent (

$\bar x$

= 0.31. Relative to male immigrants, female immigrants were 6.5 percentage points (p<0.01) likely to be selected. Moreover, those who had fluent (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.53, p<0.01) or advanced (

$\bar x$

= 0.53, p<0.01) or advanced (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.53, p<0.01) English fluency were more likely to be selected relative to those with only intermediate fluency (

$\bar x$

= 0.53, p<0.01) English fluency were more likely to be selected relative to those with only intermediate fluency (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.43). Consistency with prior experiments, these findings point to the strong internal validity of this study.

$\bar x$

= 0.43). Consistency with prior experiments, these findings point to the strong internal validity of this study.

Race and religion, the focal point of this study, are featured at the bottom of Figure 1. Relative to Christians, Muslims were selected 13.1 percentage points less often (p<0.01). Respondents are 54.95% likely to select profiles if the hypothetical immigrant is Christian; however, they are only 41.73% likely to select the profile of a hypothetical immigrant who is Muslim. The effect was the third largest after immigrants with master’s degrees and college degrees. There was no statistical difference between Jewish immigrants relative to Christian immigrants. The results from race show that relative to White immigrants, MENA immigrants were selected 4.0 percentage points less often (p<0.05). The effect size for MENA immigrants was the smallest. Black and South Asian immigrants were not selected at rates statistically distinguishable from White immigrants.

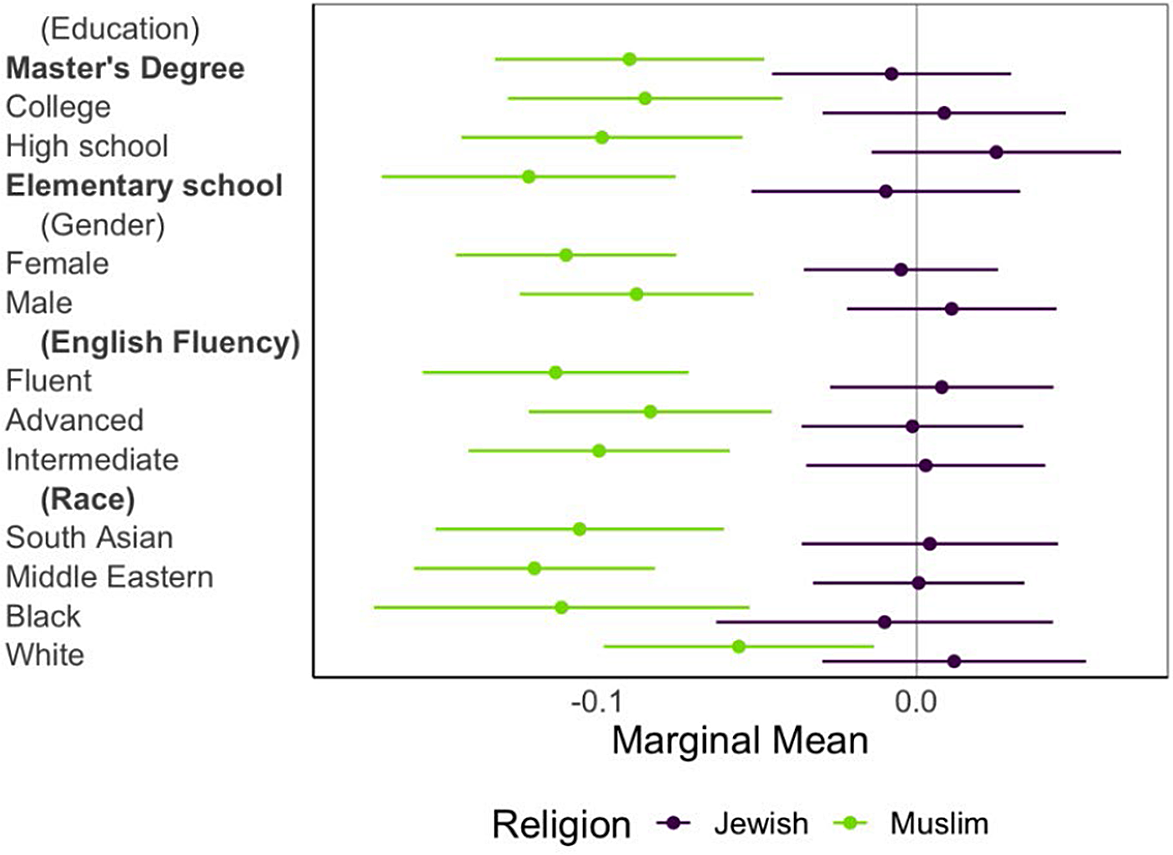

In Figure 2, we present the effect of immigrants’ attributes on the perceived likelihood they are thought to assimilate into American culture on a four-point scale. Again, female identity, higher levels of education, and increased English fluency all lead to higher assessments of cultural assimilation. Immigrants with more education are rated as more likely to assimilate into American culture relative to elementary school education. And each subsequent degree is preferred relative to the degree below it at statistically significant levels. Relative to elementary education alone, those with master’s degrees were rated as 7.0 percentage points more likely to assimilate (p<0.01). Those with college (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.72, p<0.01) and high school (

$\bar x$

= 0.72, p<0.01) and high school (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.70, p<0.01) were also rated as more likely to assimilate relative to those with only elementary education (

$\bar x$

= 0.70, p<0.01) were also rated as more likely to assimilate relative to those with only elementary education (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.66). Relative to male immigrants, female immigrants were rated 3.0 percentage points (p<0.01) more likely to assimilate. Moreover, those who had advanced (b = 0.025, p<0.01) English proficiency were rated as more likely to assimilate relative to those with intermediate English proficiency. Collectively, these results are consistent with prior results on the preferences of immigrants’ profiles.

$\bar x$

= 0.66). Relative to male immigrants, female immigrants were rated 3.0 percentage points (p<0.01) more likely to assimilate. Moreover, those who had advanced (b = 0.025, p<0.01) English proficiency were rated as more likely to assimilate relative to those with intermediate English proficiency. Collectively, these results are consistent with prior results on the preferences of immigrants’ profiles.

Figure 2. Who will Assimilate into American Culture?

Note: Figure 2 contains the marginal means for each group. The bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Immigrants with more education who are Christian or Jewish are more likely be evaluated as assimilating into American culture. High school educated or Muslim immigrants are less likely to be evaluated as assimilating into American culture.

Both Muslim (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.64, p<0.01) and MENA (

$\bar x$

= 0.64, p<0.01) and MENA (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.69, p<0.05) are statistically significantly less likely to be rated as assimilating to American culture relative to their respective baselines: Christian (

$\bar x$

= 0.69, p<0.05) are statistically significantly less likely to be rated as assimilating to American culture relative to their respective baselines: Christian (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.73) and White (

$\bar x$

= 0.73) and White (

![]() $\bar x$

= 0.72). Notably, whereas the largest substantive effect on green cards given was education, in this case, Muslim identity is the largest substantive effect on assimilation. This suggests that White Americans may view Muslims as cultural outsiders, consistent with Kalkan et al. (Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009). Even with smaller effect sizes, however, MENA immigrants are also not seen as cultural insiders, regardless of their religion.

$\bar x$

= 0.72). Notably, whereas the largest substantive effect on green cards given was education, in this case, Muslim identity is the largest substantive effect on assimilation. This suggests that White Americans may view Muslims as cultural outsiders, consistent with Kalkan et al. (Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009). Even with smaller effect sizes, however, MENA immigrants are also not seen as cultural insiders, regardless of their religion.

Thus, both MENA and Muslim identity matter; however, the effect size of Muslim identity is one of the largest, while the effect size for MENA immigrants was the smallest across our two dependent variables. To get a fuller understanding of our hypotheses, we interact religion and race. To find support for hypothesis 2, MENA-Muslims should be penalized relative to Muslims from any other background.

In hypothesis 2, we state that migrant profiles who fit a prototype of being a Muslim Middle Easterner or Muslim North African would be more likely to be excluded than those with other combinations of race and religion. To reject our null, we would need to find heterogeneity wherein only the MENA-Muslim would be penalized, but not the White, Black, or South Asian Muslim. Figure 3 and Figure 4, below, present these findings conditional on Christians. That is, each figure includes the Jewish and Muslim profiles relative to the Christian profile. We have also included these figures conditional upon race (relative to White) in Appendix 7. However, for ease of interpretation, we plot the means conditional upon religion, below.

Figure 3. Who Should be given a Green Card Conditional on Religion?

Note: Figure 3 contains the marginal means for each group conditional on religion. The bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Across every attribute, Muslims are less likely to be selected for green cards relative to Christians.

Figure 4. Who will Assimilate into American Culture Conditional on Religion?

Note: Figure 4 contains the marginal means for each group conditional on religion. The bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Across every attribute, Muslims are less likely to be evaluated as. Assimilating into American culture relative to Christians.

As seen in Figure 3, below, there is no heterogeneity based on the race of the Muslim immigrant on the likelihood of a green card given. If there was heterogeneity, we would expect to see differences between those who were Muslim by ethnoracial background; however, we see Muslims of all ethnoracial backgrounds are excluded at similar rates relative to the Christian immigrant baseline. Although Muslim immigrants are excluded relative to Christians across attributes, generally, Jewish individuals are not excluded at rates that differ relative to Christians. There are a few attributes that do differ, however. Female, college-educated, Jewish immigrants are excluded relative to Christian immigrants at a statistically significant level of p < 0.1. Moreover, Middle Eastern Jewish immigrants are also excluded relative to Middle Eastern Christians. This difference is also statistically significant at a p < 0.1 level. Although these significance levels are a bit above the convention of p < 0.05, it suggests there could be intersectional considerations between religion and racial categories for Jewish individuals.

Returning to hypothesis 1, however, Muslim immigrants were excluded at rates that were statistically significantly different relative to Christians across all attributes and levels. This provides support for hypothesis 1 over hypothesis 2; Muslim immigrants are excluded from green cards irrespective of race relative to Christians regardless of their race.

Next, we test whether we see whether the intersection of MENA-Muslim identity influences assimilation. In Figure 4, below, there is an effect of MENA-Muslim identity on assimilation. Black Muslims (

![]() $\bar x$

= −0.111, p<0.05), South Asian Muslims (

$\bar x$

= −0.111, p<0.05), South Asian Muslims (

![]() $\bar x$

= −0.106, p<0.05), and MENA-Muslims (

$\bar x$

= −0.106, p<0.05), and MENA-Muslims (

![]() $\bar x$

= −0.120, p<0.01) are rated as less likely to assimilate to U.S. culture relative to White Muslims (

$\bar x$

= −0.120, p<0.01) are rated as less likely to assimilate to U.S. culture relative to White Muslims (

![]() $\bar x$

= −0.056). After Elementary education only (

$\bar x$

= −0.056). After Elementary education only (

![]() $\bar x$

= −0.122), the largest relative substantive effect on the likelihood for respondents to say the immigrant in the profile shown would not be likely to assimilate into American culture are immigrants who are MENA and Muslim. Thus, there is some heterogeneity where White Muslims are rated as more likely to assimilate into American culture relative to Muslims from other racial backgrounds (this effect can also be seen in Appendix 4, Figure 10).

$\bar x$

= −0.122), the largest relative substantive effect on the likelihood for respondents to say the immigrant in the profile shown would not be likely to assimilate into American culture are immigrants who are MENA and Muslim. Thus, there is some heterogeneity where White Muslims are rated as more likely to assimilate into American culture relative to Muslims from other racial backgrounds (this effect can also be seen in Appendix 4, Figure 10).

Together, the findings in Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate consistent findings. The results from Figure 4 indicate that while there are no racial differences based on religious identifiers, respondents do differentiate between White Muslims and Black, MENA, and South Asian Muslims as less likely to assimilate into American culture. Thus, Muslims are evaluated as not being as likely to assimilate relative to Christians at levels that are highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). However, a closer examination shows an additional pattern within racial groups for the Muslim immigrants. White Muslims are evaluated as being more likely to assimilate relative to Middle Eastern Muslims. This suggests that within Muslim racial identities, respondents differentiate the extent of belonging in American society. Overall, however, the preference is for immigrants from another religion, regardless of race. Despite this distinction between White and MENA Muslims, the Muslim identifier alone is sufficient for individuals to be more likely for respondents to exclude them from American society.

Conclusion

Research on Islamophobia and Muslim identity in the United States and around the world has increasingly become an area of interest in research on race and ethnic politics in the United States (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Lo and Platas2019; Beydoun Reference Beydoun2013; Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2017, Reference Lajevardi2020; Lajevardi, and Oskooii Reference Lajevardi and Oskooii2018; Oskooii et al. Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2019). However, the American public and even the media often conflate Middle Easterners and North Africans with Muslims, and vice versa. We ask, given that Islam is a religious, rather than an ethnoracial category, does the White American public understand the nuances between these two categories?

We explore the relationship between Muslim identity on belonging. Although there are multiple dimensions from which we can study belonging, we focus on societal belonging. That is, who does society at large believe belongs in the United States? Here, we evaluate the role of religion and present two competing frameworks, which we empirically test using a conjoint experiment. We find that Muslim identity is more salient relative to racial identity considerations when White Americans evaluate who belongs in the United States. Muslims are evaluated as a monolithic group and the race of any given Muslim individual is irrelevant.

Although Muslim and MENA identities are often conflated with each other—that is, Muslim MENA identity is not merely an addition of racial and religious characteristics, but an identity with different experiences than Muslims who may also be Black, White, or Asian. But we find that White Americans do not discriminate against Muslim MENA individuals differently than White, Black, or South Asian Muslims.

These findings have a number of practical implications. First, research has shown that religion and country of origin together can alter perceptions of others’ ethnoracial identity (d’Urso Reference d’Urso2022). Although religion may alter perceptions along with country of origin, religion plays a singular role in how individuals are evaluated by society. Muslim Americans are a diverse ethnoracial group that experiences monolithic discrimination. And recent research shows that is how Muslims experience personal belonging in the United States. While Muslims feel “at home” in America, they are not welcomed by society at large (Chouhoud Reference Chouhoud and Stockemer2022). Thus, researchers on Muslims and Islamophobia should be careful to think through the implications of any findings if they are treating Muslims as a proxy for MENA individuals alone. Here, we find that discrimination toward Muslim inclusion reaches beyond the prototype of Muslim MENA individuals, meaning Islamophobia may be a framework that extends to more individuals, such as converts or “model minorities” who are Muslim than otherwise thought.

Second, the evidence here provides additional rationale to other research demonstrating that MENA should be categorized separately from White in the U.S. Census. Although there are certainly exclusionary attitudes toward Muslims across all races, there are also unique attitudes toward MENA individuals in our experimental treatments. Although other studies provide evidence that the category should be separated because of different social conditions that may go unnoticed (e.g., Jonny Reference Jonny2020; Strmic-Pawl et al. Reference Strmic-Pawl, Jackson and Garner2018), this follows others (e.g., Beydoun Reference Beydoun2015a; Kayyali Reference Kayyali2013) in demonstrating that the experience of MENA individuals in the United States—regardless or religious background— is distinct from that of others considered to be White Americans.

There are a number of ways this work can and should be expanded in the future. For example, there is work showing the disconnect between personal belonging of Muslims in the United States and how accepted they are by American society (Chouhoud Reference Chouhoud and Stockemer2022). Future work can include whether this experience is moderated by race. This study indicates White Americans believe White Muslims will be better at assimilating into American culture. Is this how White Muslims feel? Moreover, White Americans believing White Muslims are more likely to assimilate does not mean they will be more accepting of White Muslims relative to Muslims from other races.

Another area for expansion is to have respondents from different ethnoracial backgrounds—not merely White Americans. We selected White Americans because MENA individuals are legally classified in the United States and our questions about inclusion considered the racial hierarchy.Footnote 12 We see in the case of green cards; race did not matter when also presented with religious information. However, we see MENA-Muslims were the least likely to be rated as able to assimilate and White Muslims the most. And, since norms of racial equality differ by audience race (Bonilla et al. Reference Bonilla, Filindra and Lajevardi2022), future research should investigate if race is a more salient factor for non-White Americans.

Last, we focus specifically on the case of MENA-Muslim identity in the United States. The relationship between the racialization of Muslims and MENA individuals in the United States is not necessarily applicable to the experiences of Muslims and MENA individuals in different country contexts. For example, in the UK, the conflation may be between South Asians and Muslims (e.g., Abbas Reference Abbas2004); in France, it may be for Afro-Muslims (e.g., Adida et al. Reference Adida, Laitin and Marie-Anne2016). Future research might investigate the roles of religion and race and the intersectionality of the two in other country contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.7

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank James Druckman, Alvin B. Tillery Jr., J. Seawright, S. R. Gubitz, Kumar Ramanathan, Matthew D. Nelsen, Margaret Brower, and Youssef Chouhoud for comments on early drafts. We also thank S. R. Gubitz for insights on coding the survey. Finally, we thank Georgia Caras and Michelle Sheinker for their excellent research assistance.

Funding Declaration

The data collection effort was funded through the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy at Northwestern University.

Ethical Statement

The study was approved by the NU Institutional Review Board (#) and was deemed exempt.