The 2016 United States Presidential election was one of the most diverse to date: almost one in three eligible voters was non-White (Krogstad et al. Reference Krogstad, Hugo Lopez, Lopéz, Passel and Patten2016), although the future implications of this ongoing demographic change are tempered by non-White voters’ consistently low turnout rates. Mobilization is one of the most effective ways to significantly boost non-White participation rates, thereby increasing the potential for non-Whites to engage in political activities, and specifically to alter electoral outcomes (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993). Yet traditional political institutions, such as campaigns and political parties, tend to focus their limited resources on mobilizing likely voters, and to almost exclusively electoral activities (voting, registering, etc.). Non-Whites often are less well resourced, have intermittent voter turnout rates, and a high proportion of new voters, and so are often ignored by partisan institutions leveraging limited resources. Further, the increasingly abrasive political environment increases party incentive to promote nativist tendencies in lieu of courting new and minority voters as a way of attempting to “balance their current constituencies against possible future ones” (Erie Reference Erie1988; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2009).

While disparities are acknowledged, the mobilization literature lacks a cohesive framework for accounting for differences in partisan contact between Whites and non-Whites. Further, few studies examine the simultaneous role of civic and community institutions’ efforts to mobilize non-White communities. Instead most studies emphasize or address the mobilization of only one racial group (Michelson Reference Michelson2003a; Reference Michelson2003b; Ramirez Reference Ramirez2013), while studies that are not race specific are completed among mostly White participants and emphasize voting behavior (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Phillip Converse, Warren Miller and Donald Stokes1960; Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).Footnote 1 This paper endeavors to develop a framework that distinguishes between informal (nonpartisan) civic or community institutions and formal (partisan) political institutions, and acknowledges the distinct effect of contact on political participation beyond voting across racial groups.Footnote 2

Our analysis is premised on the racial disparity in traditional political organizations’ mobilization efforts that target primarily White voters who tend to participate at higher rates than racial minorities (File Reference File2013). We ask and offer a counterfactual: if racial minorities were contacted more, and contacted by organizations or people that look like them or are from their community, would they participate in political activities at rates comparable to Whites? To that end, we argue that three aspects of contact—intensity of contact, co-ethnic contactFootnote 3, and type of organizational contact—matter for non-White political participation in ways that differ from Whites. While intensity of contact should increase the participation of all racial groups, more intense outreach promises to have a larger positive impact on groups historically excluded in American politics. Co-ethnic contact should increase the participation of non-Whites, whose inclusion in traditional politics is contested resulting in distrust of the political system, as it taps into community connection rather than trust in the political system. Thus, outreach by someone of their own group may bridge the trust gap and result in positive effects on participation across a variety of political activities. Lastly, outreach efforts by civic or community institutions promise to have a larger impact on the participation of Asian Americans and LatinosFootnote 4 than those by political institutions. This is because a large component of both groups is either immigrant or immigrant-derived, and therefore needing additional outreach and education in order to be effectively brought in as participants in the American polity.

We draw on the Collaborative Multi-racial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) to evaluate the relationship between types of outreach efforts and participation outcomes (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Hancock, Manzano, Ramakrishnan, Ramirez, Sanchez and Wong2008). Because mobilization efforts by a range of organizations foster participation both in and out of the voting booth, we include non-voting activities in an analysis of participation outcomes alongside voting (Han Reference Han2016). We use descriptive statistics to illustrate racial distinctions in mobilization and participation, and then ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to predict the mobilizing power of increased community based contact on non-White political participation.

It is important to note that although we develop a causal account of the relationship between institutional contacts and political engagement, we employ a cross-sectional survey to test the implications derived from our framework. The analysis presented in this paper is therefore correlational in nature. However, we offer a comprehensive theory for understanding the relationship between mobilization and participation that places Whites in a comparative framework with Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans, and posit that culturally competent efforts targeted to the needs of non-White groups promise to bring them into the polity. We build on research identifying the under-mobilization of new voting groups as democratically problematic, and the theory and evidence suggest that efforts to incorporate these groups will yield participatory dividends. We therefore lay the necessary groundwork for, “scholars and pundits [who] pour over election results and lament ‘underperformance’ of minorities,” to move forward with a focus on the institutional factors that can enhance the equal participation of an increasingly diversifying electorate (Barreto Reference Barreto2018, 187).

RELEVANT LITERATURE

The conventional wisdom on political participation focuses on socioeconomic status and mobilization as the two mechanisms driving engagement. Education, wealth, and civic skills increase political engagement by facilitating resources like time, knowledge, and energy to participate (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Phillip Converse, Warren Miller and Donald Stokes1960; Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Wolfinger and Rosenstone Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980). Being asked to participate is equally important and can help overcome socioeconomic deficits, and the importance of resources and mobilization to participation extends to a wide variety of political practices beyond voting, like signing a petition, attending protests, donating to campaigns, and so forth (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Researchers identifying the importance of mobilization have focused on efforts by political institutions, especially parties and campaigns (Caldeira, and Patterson Reference Caldeira and Samuel C.1990; Wielhouwer and Lockerbie Reference Wielhouwer and Lockerbie1994). Parties and campaigns have routine, electoral incentive to mobilize voters, but this incentive also leads to institutional neglect of sub-groups of voters deemed unlikely to participate: the poor, the young, and people of color (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993). This paper focuses on the role of civic organizational contact of non-Whites as an avenue for overcoming neglect by political parties and campaigns despite the increased electoral presence of these groups.

The Electoral Incentive to Overlook People of Color

The demographic shifts of the American electorate are clear: a majority–minority U.S. population is on the horizon due to the dramatic and ongoing growth in Latino and Asian American populations (Frey Reference Frey2018). According to a recent Pew Hispanic Report, there was an estimated 27.3 million eligible Latino voters for the 2016 presidential election, representing a 40% increase since 2008 (Krogstad et al. Reference Krogstad, Hugo Lopez, Lopéz, Passel and Patten2016). Asian Americans made up approximately 5% of the U.S. population as of 2008 (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011) and are currently the fastest growing racial group (“The Rise of Asian Americans” 2013). Yet, Latino and Asian American voters are consistently overlooked by partisan mobilization efforts (Leighley and Vedlitz Reference Leighley and Arnold1999; Lien, Conway, and Wong Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2004; Lien et al. Reference Lien, Christian Collet and S. Karthick2001; Uhlaner, Cain, and Kiewiet Reference Uhlaner, Cain and Kiewiet1989; Wong Reference Wong2000; Reference Wong2006). This is because electoral calculations by political parties and campaigns create disincentives for non-White mobilization, historically premised on their relatively small size, or expectations of electoral capture (Frymer Reference Frymer2008).Footnote 5

Black Americans have achieved the most institutional inclusion, but risk electoral capture backlash. Latinos are verging upon electoral capture, a condition exacerbated by the fact that their votes are not yet considered essential to national electoral success. Asian Americans, the smallest of the three groups, have been historically the most split between parties, but in recent years anti-immigrant rhetoric may be pushing them firmly into the Democratic Party (Peters Reference Peters2016).Footnote 6 All three groups are therefore threatened by electoral capture, and their relative size makes them a low value target for institutional outreach.

As a result, non-Whites often compete for minimal attention from political institutions which, at best, results in the neglect of non-White groups. Yet at its worst, a preference for White voter mobilization historically resulted in a partisan incentive to actively vilify non-Whites (Barreto and Nuño Reference Barreto and Nuño2011; Gay Reference Gay2002; Michelson Reference Michelson2003a; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003a; Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b). These overtures can be both overtly and implicitly racist (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2014; Jacobson Reference Jacobson2008; Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2005; Wilson Reference Wilson2001). Such denigration erodes trust for partisan institutions among new voting and low-turnout populations, pushing them further to the political margins (Barreto and Nuño Reference Barreto and Nuño2011; Gay Reference Gay2002; Michelson Reference Michelson2003a; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003a; Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b). Neglect, moreover, reinforces already low levels of political efficacy documented by scholars elsewhere, leading non-Whites to increasingly subscribe to the belief that elected officials do not care about or respond to the needs of people like them (Barreto Reference Barreto2018; Nuño Reference Nuño2007).

More importantly, the presumption that non-Whites will continue to fail to participate is unfounded. Research has found that the act of registration, regardless of whether that act happens as a result of age, education, or naturalization, “appears to mark a decisive cut-point in the level of political interest” which then causes “low resource voters [to] act more like high resource voters” (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Gimpel and Dyck2006, 158). Further, voting itself predicts the likelihood of voting in the future, and voter mobilization and turnout is likewise associated with participation in other types of activities beyond voting (Finkel Reference Finkel1985; Green and Shachar Reference Green and Shachar2000; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2014). As such, political mobilization works to incorporate citizens into the polity, both inside and outside the voting booth (Barreto Reference Barreto2018; Ramirez et al. Reference Ramirez, Solano and Wilcox-Archuleta2018). Neglect in mobilizing communities of color to the ballot box thus contributes to a self-reinforcing cycle of neglect, which in turn results not only in low voter turnout, but also in decreased civic engagement and diminished political incorporation overall. Put simply, Ramirez et al. write, “the stakes go beyond a single election outcome; the story here is about the political incorporation (or the continued lack thereof) of some groups over others, to the detriment and erosion of American democracy” (Reference Ramirez, Solano and Wilcox-Archuleta2018, 158).

Within this context, then, we push to expand the mobilization literature beyond the effect of partisan contact, which is traditionally focused on White political engagement. Further, the tradition of neglect and vilification by traditional partisan institutions produces a distrust of those same institutions for non-White voters, making nonpartisan mobilization efforts more successful. This supposition is supported by research into Black participation, as well as other marginalized populations that have had to look to informal political institutions to gain entry to formal politics.

Incorporation in the Face of Partisan Neglect

Community based organizations facilitated the participation of the Black community by providing institutional linkages necessary for participation in the face of partisan institutional neglect. These alternative mobilization avenues emerged to increase pressure on political institutions to be more inclusive of Blacks, build civic and political capital through non-governmental institutions, and center the Black church and schools as important sites of political socialization (Barker and McCorry Reference Barker and McCorry1976; Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Nelson and Meranto Reference Nelson and Meranto1977; Walton Reference Walton1994; Walton and Orr Reference Walton and Orr2005). Further, these organizations helped develop a politicized racial identity, and increase political efficacy (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Shingles Reference Shingles1981; Walton Reference Walton1994). More recently, however, the importance of the Black church and racial identity to predicting Black behavior and attitudes has declined, while mobilization efforts by institutions like the Democratic Party have, in turn, become key motivators for their turnout (Philpot, Shaw and McGowen Reference Philpot, Shaw and McGowen2009). In other words, the power or necessity of community based organizations (CBOs) to Black participation has diminished as their inclusion in traditional partisan institutions has increased. This indicates a trajectory of Black political incorporation that began with community based organizations producing a higher turnout rate in the face of partisan neglect, and resulted in a marginal degree of representation for Blacks who now earn sustained attention from parties and campaigns. It is important to note that much of this success was rooted in mobilizing Black citizens to participate broadly, both in and out of the voting booth.

Examples of the mobilizing capacity of nonpartisan community based organizations are not limited to Black Americans. Schools were a primary site of Chicano youth mobilization in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Haney-Lopez Reference Haney-Lopez2003). Anti-poverty organizations were instrumental to organizing the poor during the same time period, leading to important wins in the area of public housing and welfare rights (Ernst Reference Ernst2010; Juravich Reference Juravich2017; Reese and Newcombe Reference Reese and Newcombe2003). More recently, labor unions have played an important role in mobilizing immigrants, even though they are barred from voting as non-citizens (Terriquez Reference Terriquez2011; Varsanyi Reference Varsanyi2005). In short, nonpartisan organizations have consistently provided marginalized populations outside the mainstream of politics with alternative means of engaging in American politics and with elected representatives, historically and now.

Community based organizations likewise are often culturally competent in their tactics to mobilize marginalized populations, increasing the likelihood that they will do so successfully (Stevens and Bishin Reference Stevens and Bishin2011). This in part explains the success of co-ethnic contact, which serves as a signal that their interests may be better represented than before any representation had been achieved (Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003a; Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b). These views are supported by Zepeda-Millán's account of the power of informal organizing through activities like soccer leagues, which increased widespread participation in the 2006 immigrant's rights marches (Reference Zepeda-Millán2017). In other words, co-ethnicity, either via organizer, leader, or through ethnic centered organizations, engenders greater trust than do mainstream political actors and institutions (Barreto and Nuño Reference Barreto and Nuño2011; de la Garza, Abrajano, and Cortina Reference De la Garza, Abrajano and Cortina2008; Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2013; Michelson Reference Michelson2003b; Ramakrishnan Reference Ramakrishnan2005; Wong Reference Wong2006; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Junn2011). This trust functions to improve the belief in the importance of participating and in the value of collective action. Likewise, Ramirez et al. (Reference Ramirez, Solano and Wilcox-Archuleta2018) find that nonpartisan institutions are more likely to target immigrants and Spanish speaking Latinos, further expanding the reach of these nonpartisan organizations and also demonstrating their willingness to include all members of the Latino community. While the literature has focused on Latino participation, it suggests that nonpartisan organizations can also bring a level of cultural competency to the mobilization of other communities of color, which can explain the success of their mobilization efforts.

How Community Based Organizations Facilitate Participation

At first glance, it may appear that CBO strategies of engagement do not differ significantly from those of traditional partisan organizations, such as parties and campaigns (Leighley Reference Leighley2001). We argue that, beyond differences in the populations they target, CBOs significantly differ in their approach to voter incorporation. While parties work to mobilize individuals already possessing of the time, interest, and resources for a particular event, CBOs emphasize organization in addition to mobilization. This includes not only asking people to participate, but also showing them how, giving them support, and cultivating a sense of importance around their actions (Christens and Speer Reference Christens and Speer2011; Klofstad and Bishin Reference Klofstad and Bishin2013; LeRoux and Krawczyk Reference LeRoux and Krawczyk2014; Owens Reference Owens2014; Terriquez Reference Terriquez2011; Varsanyi Reference Varsanyi2005). For these reasons, the engagement that develops out of CBO contact builds the necessary framework for sustained civic engagement over time in populations that would otherwise be neglected and excluded from partisan mobilization efforts (Christens and Speer Reference Christens and Speer2011).

Such organization benefits both voters and CBOs. Individuals gain access to the political realm, and CBOs gain the support of political actors who are incentivized to participate out of a sense of allegiance to an organization that has helped them. Owens (Reference Owens2014) refers to this as “the strategic exchange of resources,” and his work demonstrates that CBOs are central to helping even those least likely to participate (ex-offenders) to overcome participation barriers (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014). Han identifies this strategic exchange as a double-barreled approach by CBOs especially adept at “getting people to do stuff” (Reference Han2014, 1), which is particularly significant for marginalized communities that are overlooked by partisan mobilization efforts.

Finally, not only are CBOs well positioned to fill the civic void left by parties and campaigns, but these organizations also respond to a different set of incentives than do partisan institutions. Political parties and campaigns are incentivized to mobilize as many people as possible to make donations and turnout to vote in order to win elections. Community based organizations, in contrast, are more concerned with forwarding a very narrow agenda. Motivating political actors to electoral participation and the lobbying elected officials is then a means to that goal, rather than an end in itself. Further, many CBOs are interested in building the human capital in the communities they serve for the express purpose of betterment of that community. For some CBOs, such as churches and schools, the task of organizing their membership, building leadership capacity and civic skills necessary to political participation is vital to the persistence of the institution itself.

In short, where other scholars assume that the sorts of strategies engaged by parties and campaigns do not differ in analytically important ways from those engaged by community based organizations (Leighley Reference Leighley2001), following Han (Reference Han2009; Reference Han2014), we assume the opposite. Indeed, organization undertaken by nonpartisan institutions is key to mobilizing participation among marginalized populations. Moreover, minorities and the poor may be targeted by community based organizations for the same reasons they are neglected by formal partisan institutions: because their narrow interests have been historically neglected within the political realm.

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

Our argument is premised on the understanding that the American political system defaults to a “likely voter” that is primarily White. This has necessitated alternate forms of political engagement for non-White communities that have not received the same level of attention from political actors and institutions. To that end, we theorize that the type and intensity of outreach efforts engaged in by nonpartisan institutions will have a stronger effect in mobilizing non-White populations. We develop three interlocking hypotheses derived from our theoretical framework regarding the differential impact of institutional contact on political participant among racial subgroups: that the intensity of contact, the ethnicity of the contacting individual or organization, and the type of institution impacts the effectiveness of outreach to non-White political participation.

First, we address the simplicity of outreach—the most effective way to get individuals involved is to ask them to participate. We therefore argue that all racial groups will be responsive to political mobilization efforts and requests to participate. The testable implication derived from this proposition is that a greater number of requests to participate will be positively related to participation. We refer to this as the intensity of contact hypothesis, and we expect that it will hold across all racial groups. However, non-White communities have historically been neglected by, or actively excluded from, the mobilization efforts of parties and campaigns. As such, the size of the positive impact of intensity of contact on participation outcomes will be larger for non-Whites, who even when controlling their previous voting behavior or competitive status, are less likely than Whites to be contacted overall. This generates the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

More institutional contacts will lead to higher rates of participation for all racial subgroups.

Hypothesis 1a

The size of the effect of number of institutional contacts will be larger for non-Whites than Whites.

We next argue that intra-group mobilization through institutional co-ethnic contact has the potential to increase political participation among minorities. The at-times hostile political environmentFootnote 7 against Blacks, Latinos, Asian Americans, and immigrants in combination with the history of neglect makes distrust of political elites a rational response for non-White communities (Barreto and Nuño Reference Barreto and Nuño2011; Gay Reference Gay2002; Michelson Reference Michelson2003a). As such, the second testable implication of our theoretical framework is that institutional co-ethnic contact will be positively associated with political participation among non-Whites. Our understanding of co-ethnic contact is largely derived from research on Latinos, but we expect other racial subgroups will have a similar positive response due to their similar experiences of antagonism and ostracism from the established political regime. This leads to the following co-ethnic contact hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Institutional contacts from a co-ethnic will lead to higher rates of participation only for non-Whites.

The final theoretical proposition we consider is that mobilization efforts by civic and community institutions will be more important for Asian Americans and Latinos, who are currently neglected by mainstream political institutions, than for Blacks. Blacks enjoy some recognition from the Democratic Party as an important voting bloc, and thus are increasingly incorporated into party mobilization efforts (Philpot, Shaw, and McGowen Reference Philpot, Shaw and McGowen2009). We theorize that their newly incorporated status decreases the impact of nonpartisan outreach on Black participation levels. In contrast, we hypothesize that Asian Americans and Latinos will demonstrate higher rates of participation following contact by a nonpartisan (and therefore, more trusted) institution as compared with partisan contact. We refer to these as the institutional contact hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

Contact by nonpartisan (civic and community) institutions will increase participation among Latinos and Asian Americans.

Hypothesis 3a

Partisan and nonpartisan contact will have the same impact on Black participation rates.

We expect that successful mobilization will be reflected in a wide variety of activities inclusive of but not limited to voting. Community based organizations provide routine opportunities for engagement outside of elections, and mobilization by all kinds of institutions enhance and support the incorporation of citizens into the polity, which should be reflected outside the voting booth (Han Reference Han2016; Ramirez et al. Reference Ramirez, Solano and Wilcox-Archuleta2018; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2014). As such, our explicit expectation is that mobilization around elections has positive spillover effects for civic engagement, conceived of broadly.

DATA AND METHODS

We use the 2008 CMPS dataset with 4,563 valid respondents, all registered voters from the 2008 Presidential election. The benefit of the CMPS, as Wong (Reference Wong2015) and others note, is its robust sampling of Black Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos, in addition to Whites.Footnote 8 This makes it possible to compare patterns of self-reported behavior across all racial groups.Footnote 9 Further, the CMPS was available in English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, and Vietnamese, and respondents could choose their language of interview, facilitating both the response rate and ability of respondents who are not native English speakers to participate. This is particularly important when examining racial groups with large immigrant populations, such as Latinos and Asian Americans. Moreover, the CMPS is unique in the measures important to our analysis. The survey included several questions measuring whether one had been mobilized to participate as well as participation outcomes. To our knowledge, no other survey both includes the requisite measures to the questions under study and boasts a robust sample of the racial subgroups in question.Footnote 10 The 2008 CMPS therefore offers an important opportunity to assess the viability of our theory, and our analysis lays the necessary foundation for future experimental work on the topic at hand.

Our primary outcome variable is a nine (9) item political participation index. We chose to create this variable both to account for the various ways different racial groups participate as well as to effectively measure respondents’ degree of self-reported engagement. Five of the nine items measure traditional or formal modes of participation: whether the respondent voted in the 2008 general election, attended a political meeting or speech in support of a particular candidate or party, worked for a candidate or party, donated money to a candidate or party, or wrote a letter or email to an elected official. We additionally included four acts that are not campaign-specific but are still political: whether the respondent in the past year took part in a protest or demonstration, tried to convince family or friend to vote, read or posted a comment about politics on a blog or website, or used a social networking page or listserv to talk about politics.

We include a wide variety of political acts in our measure of participation for a number of reasons. Groups that are historically politically marginalized are more likely to participate informally, since such activities offer a lower barrier to entry; successful mobilization is likely to manifest in a broad spectrum of activities beyond voting; and the measure of voter turnout in the CMPS is self-reported and therefore threatened by social desirability bias, which research demonstrates does not likewise bias self-reports of other types of activities (Holbrook and Krosnick Reference Holbrook and Krosnick2010a; Reference Holbrook and Krosnick2010b; Persson and Solevid Reference Persson and Solevid2013; Zukin et al. Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Delli Carpini2006). A robust analysis of the impact of mobilization efforts on political engagement should therefore include participatory measures inclusive of but not limited to voting.

We begin with the premise that racial groups have a different experience of and relationship to the political system. As such, we model each group separately. This allows us to identify which of our explanatory and control variables affect each group's rate of political participation. We then calculate the fixed effects of the variables of interest on participation outcomes, as well as the predicted levels of participation for each group from our race-specific OLS regression models.Footnote 11 We have three primary explanatory variables to test our hypotheses about racial minority political mobilization: intensity of contact, co-ethnic contact, and type of institutional contact. All three measures are developed from the CMPS questions asking whether respondents were asked to register or to vote, by whom (person or organization), the party of the contacting agent, and their ethnicity.Footnote 12

Given the disparity in political outreach between racial groups, we hypothesize that more frequent contact encouraging participation (or a greater intensity of contact) will have a stronger influence on Latino, Asian American, and Black voters as compared with Whites. To measure intensity, we count the number of different people or organizations that contacted the respondent.Footnote 13 Possible responses include a candidate running for office or their campaign, political party representative, an independent group not directly tied to the candidates, or a nonpartisan organization working in your community. Respondents could answer affirmatively to each response, making a total of four “types” of contact possible. This variable ranges from 0 (no contact) to 2 (for 2 or more types of contact).Footnote 14

We are also interested in the effect of the type of organizational contact on political participation rates. We hypothesize that contact by a nonpartisan civic or community institution will have a larger influence on Asian American and Latino participation than contact by a party or campaign due to an historical distrust of traditional partisan institutions. In contrast, we expect that there will be no difference between partisan and nonpartisan group contact on both Black and White participation rates given established pattern of outreach to both racial groups by both types of organizations. We created two variables from the same question used to measure intensity: “Who contacted you?” The variable “partisan contact” indicates a candidate running for office or a political party representative, and “nonpartisan contact” represents outreach by community or other nonpartisan organizations.

While the literature regarding co-ethnic mobilization mostly focuses on Latinos, we developed a “co-ethnic contact” hypothesis to test whether the effect of co-ethnic mobilization applies to all racial groups. Respondents who reported having been asked to register or to vote were also asked about the race of the person who contacted them. We created dichotomous variables for each of the racial categories (Latino, Asian American, Black, and White) to be applied in the relevant regression models, with the “0” term referring to contact from a person or organization of any race other than that of the respondent.

A significant portion of the literature addresses the differing impact of outreach and other traditional demographic features on immigrant political participation. To account for this, we created a dichotomous variable “Born in US” to delineate between immigrant and later generations. This variable is only used in regressions for Latino and Asian American respondents since upward of 95% of White and Black respondents are born in the USA.

All other socioeconomic control variables are included in our regressions: party, home ownership, income,Footnote 15 education, gender, and age. We also account for religion as a major component of community and cultural identity, along with the direct link between church and political mobilization particularly within the Black community. Recent work demonstrates that religion may continue to influence racial identity and political attitudes among racial subgroups (Wong Reference Wong2015), and high church attendance has been shown to correlate with high levels of political engagement, providing ample justification for inclusion of this variable (McDaniels Reference McDaniel2008; Putnam Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Wong Reference Wong2015). To that end we include a variable for church attendance; this is a six-point scale ranging from “never” (value = 1) up to “more than once a week” (value = 6). We also created a dichotomous “co-ethnic church” variable to account for the community aspect of religion, which may be amplified if one attends with a predominantly co-ethnic congregation.

Lastly, we include a dichotomous variable measuring whether respondents report having personally experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly on account of their race. A growing body of research demonstrates that perceived racial discrimination and resulting feelings of group threat are linked to increased political participation (Bowler, Nicholson, and Segura Reference Bowler, Nicholson and Segura2006; Pantoja, Ramirez, and Segura Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and Segura2001; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003a; Reference Pantoja and Segura2003b; Pedraza Reference Pedraza2014). Further, we premise our framework on the idea of institutional neglect, and discrimination may point to a way of identifying perceptions of neglect more broadly. Thus, perceptions of discrimination, which may increase political engagement, may also alter perceptions of institutional neglect and result in further increased participation. For the same reasons, we also include a dichotomous measure of racial linked fate.

Findings

Our paper is premised on the idea that White voters are consistently asked to participate at higher rates than other racial and ethnic groups, a fact that is reflected in the CMPS data (see Table 1). White respondents reported an average of .44 contacts as compared with Blacks (.41), Latinos (.31), and Asian Americans (.28). A χ2 test found that these differences are statistically significant.Footnote 16 There is one anomaly to the pattern of Whites being contacted most often: Black respondents reported being “mobilized”—asked to participate, vote, or engage—more frequently by nonpartisan institutions than did White respondents (13.3 and 11.6%, respectively). We conducted logistic regression to predict the effect of race on the likelihood of being contacted at all, and then contacted by partisan and nonpartisan institutions.

Table 1. Levels of institutional contact and political participation, among racial subgroups in the CMPS

We found that being Black produced no significant difference in likelihood of mobilization as compared with Whites. However, Latinos and Asian Americans are predicted to be contacted 6.4 and 6.7% less than Whites, respectively. Both findings are significant to the p < .01 level. The findings are similar for predicting partisan contact (3.0 and 6.0% less) and nonpartisan contact (4.2 and 3.8% less) for Latinos and Asian Americans as compared with Whites. The likelihood of Black mobilization by either partisan or nonpartisan institutions was not statistically different from that of White voters. Given the connection between mobilization and participation, it is unsurprising that Whites also report the highest levels of participation: White respondents have the highest mean score on the participation index (3.1) and are closely followed by Blacks (3.0, see Table 1).

We argue that communities of color would participate at higher rates if they were also mobilized at greater levels. Given the historical context of institutional neglect, we test whether greater intensity of contact (as measured by having been asked by multiple sources to register), mobilization via nonpartisan civic and community institutions, and co-ethnic mobilization will have a positive effect on non-White political participation.

Our first hypothesis rests on the theory that the simplest way to increase participation is by asking (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). We predict that a larger number of “asks” to participate will produce a higher rate of participation for all racial groups (Hypothesis 1). In the observed data, Whites participate at the highest rate of any group (3.1), followed by Blacks (3.0), Latinos (2.6), and Asian Americans (2.4), regardless of mobilization efforts. In our regression models, increased contact produces positive and significant coefficients for all racial groups, supporting our first hypothesis, and providing continued support for past research into the significance of mobilization efforts to all racial groups’ political participation.

However, we further argued that the size of the impact would be larger for non-Whites than for Whites (Hypothesis 1a), and again find support for this claim. While frequent contact increases White respondents’ average participation score by .15 (p < .05), it increases participation for Latinos by .22, Asian Americans by .48, and Blacks by .41. Differences for all non-White predictions are statistically significant at the .01 level. Importantly, these effects produce higher predicted rates of participation for both Asian American and Black voters as compared with Whites. While Latinos also experience positive effects from outreach, they are predicted to continue to have a lower level of participation than the other three racial groups (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The predicted mean score on our participation index with mobilization from two or more types of organizations. Lines represent confidence bands at p < .05.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that being asked to participate by a co-ethnic will positively impact participation for Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans. Although it is primarily Latino politics literature that demonstrates the impact of co-ethnic mobilization, we theorized that the underlying logic behind co-ethnic mobilization would extend to Blacks and Asian Americans as well, given patterns of distrust established by the White-dominated traditional political structure. However, our findings do not support this theory (Table 2). Instead, we find that the mobilizing effects of co-ethnic contact holds only among Latinos. This supports existing research, but also identifies the limitation in generalizing specific theories of ethnic political mobilization to other racial groups. In other words: not all non-White groups respond or participate in the same way to co-ethnic appeals. This may be due to the lack of national and ethnic cohesion amongst Asian American respondents. While most Latinos at least share a common language, Asians do not, making a generalized pan-ethnic “Asian American” appeal less effective. Co-ethnic appeals may be less successful for Blacks who, as discussed above, are already somewhat accepted and courted by traditional partisan institutions.

Table 2. The impact of intensity of contact and co-ethnic ask on political participation, among racial subgroups in the CMPS

Standard errors in parentheses; *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

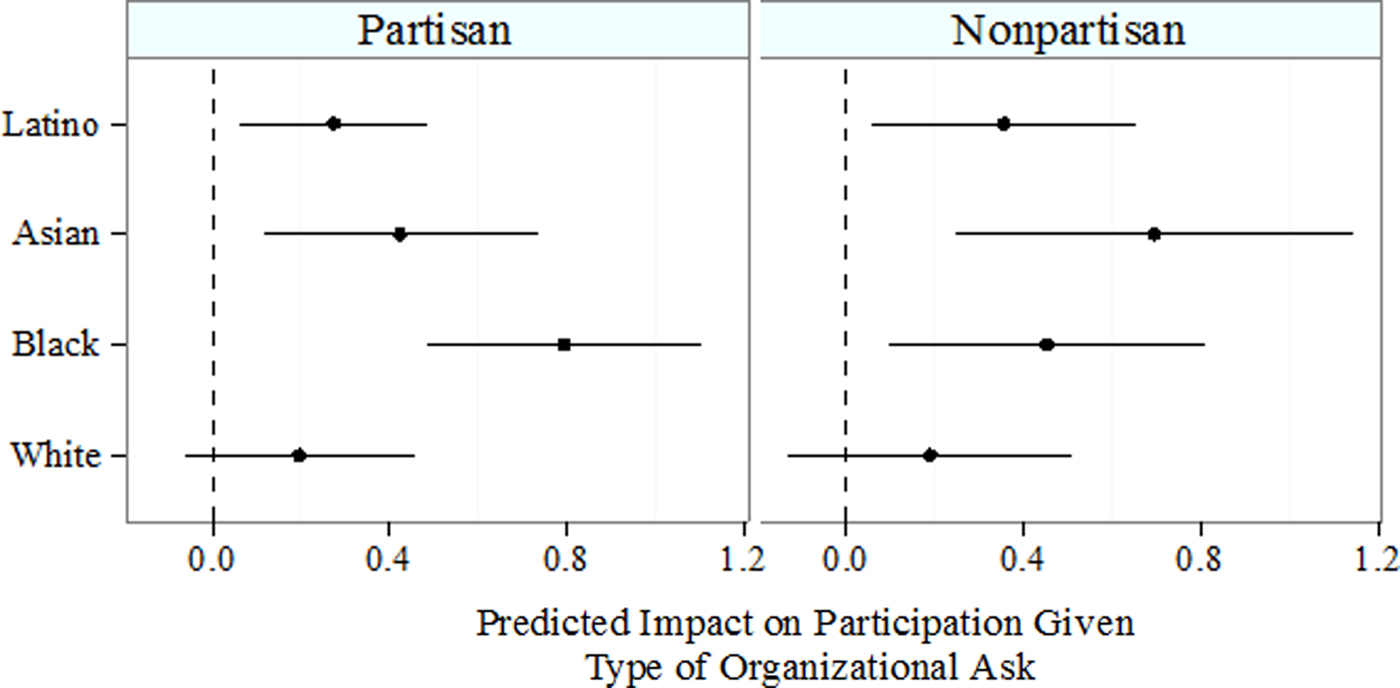

This leads to our third hypothesis, which addresses a key facet of on-going institutional neglect: the difference between outreach by partisan versus nonpartisan institutions on political participation. We argue that being contacted by a nonpartisan civic or community institution will have a positive impact on the participation of non-Whites, but with two qualifications. We theorize that the size of the impact will be greater than that of being contacted by a partisan institution among Asian Americans and Latinos (Hypothesis 3), while nonpartisan and partisan contacts will yield the same or similar results in participation rates for Black respondents (Hypothesis 3a). To test this, we estimated the effect of being contacted by a partisan versus a nonpartisan institution on each racial groups’ predicted rates of participation. Those who were never contacted serve as the comparison group. We omitted the variable “total number of contacts” from our regressions to avoid collinearity bias, since the variables are based on the same underlying questions asked by the survey (see Table 3).

Table 3. The partisan and nonpartisan contact on political participation, among racial subgroups in the CMPS

Standard errors in parentheses; *p < .10, **p < .05, *** p < .01.

We find that nonpartisan institutional contact positively and significantly affects Latino, Asian American, and Black participation rates, but not that of Whites. As predicted, among Asian Americans and Latinos the size of the impact of nonpartisan institutional contact is larger than is the size of the impact of partisan institutional contact, in support of Hypothesis 3. Figure 2 displays the marginal effects by the type of contact among racial subgroups. The difference is particularly marked for Asian Americans, who are most neglected by partisan institutions. Being contacted by a nonpartisan group increases the expected value of participation among Asian Americans by about .75 items on our participation scale. In contrast, nonpartisan contact increases Latino participation by about .45 items. Clearly, where partisan outreach fails, nonpartisan institutions can and do pick up the slack in Asian American and Latino political mobilization.

Figure 2. The impact of being asked by a partisan organization to register to vote, compared with the impact of being asked by a nonpartisan organization among racial subgroups. Lines represent confidence bands at p < .05.

We further theorized that partisan and nonpartisan contact would have a similar effect on the participation rate of Blacks given their relatively secure (if often ignored) placement within partisan politics and the Democratic Party. The results indicate that being contacted by a political party or campaign has a larger overall effect than does being contacted by a community group. Being asked by a partisan institution increases the expected value of Black participation by about .81 items on the index, compared with an increase of only .4 that comes from being asked by a nonpartisan institution. This supports prior research emphasizing the importance of Democratic Party outreach to Black participation levels, while the impact of churches and racial identity have declined (Philpot, Shaw, and McGowen Reference Philpot, Shaw and McGowen2009). Regardless, we were not anticipating finding a weaker effect for nonpartisan outreach, particularly given the strong role that CBOs historically played in Black incorporation and mobilization. Thus, though Blacks have secured a larger slice of partisan institutional attention previously reserved only for Whites, the simultaneous decline in CBO outreach shifts much more responsibilities for mobilization onto partisan institutions. This runs the risk of regressing Black political incorporation given the ongoing nature of electoral capture (Frymer Reference Frymer2011).

Formal versus Informal Modes of Participation

We deliberately created our nine-item index of political participation to include both formal and informal modes of political participation in order to account for the varying patterns of participation exercised by each racial group. We did not want to preference acts, such as voting, over other costlier acts, such as attending a protest. Our scale is therefore indifferent to which kinds of acts respondents take part, and instead assesses their self-reported political engagement overall. However, it is worthwhile to identify if mobilization has a distinct impact on different activities since some participatory acts—such as contacting an elected official—may have larger political implications than others—such as writing on a blog. To complete this analysis, we ran separate regressions for each participation act by race, using the same predictor variables as in the models presented above.Footnote 17

We found little similarity between racial groups and their response to mobilization when examining the individual acts. Asian American response to both partisan and nonpartisan outreach is entirely isolated to traditional acts: attending a political speech, volunteering for a campaign, donating money, and writing letters.Footnote 18

In contrast, partisan outreach produces a positive coefficient for Black respondents in predicting all of our participation measures with the exception of writing letters and voting. Nonpartisan outreach is significant and positive only in predicting Black attendance of political speeches, volunteering, and their belonging to a political listserv. This further illustrates our above finding that partisan outreach has a stronger relationship to Black political participation than nonpartisan contact.

Whites, as we already saw, are virtually unaffected by any kind of contact, as they are likely to participate at higher rate overall. Partisan mobilization efforts were only significant in increasing the probability of White voters writing letters to elected officials, while nonpartisan mobilization positively indicate they will vote or follow a listserv.

Institutional contact had the most varied influence on Latino respondents. Partisan contact corresponded with increased Latino likelihood of following a listserv, volunteering, donating money, and writing letters. Nonpartisan contact corresponded to an increased likelihood of encouraging others to vote, attending a speech or rally, volunteering, or writing letters. Co-ethnic contact also had a narrow effect on Latino participation, predicting a significant increase in Latino likelihood of attending a protest or a political speech, only.

The most striking finding of these analyses is that the institutional type of contact—co-ethnic, partisan, or nonpartisan—did not influence outcomes on reported voter turnout, one of the nine activities measured. While we push for greater acknowledgment of the numerous ways individuals make their political preferences known, the fact remains that power comes through voting as a coherent bloc. This is the crux of Black participation literature—that through the continued and ongoing efforts of nonpartisan organizations, Blacks increased voter turnout levels that led to both some level of descriptive representation and increased attention from traditional partisan organizations. Latino and Asian American communities have significantly lower rates of voter turnout, and subsequently lower rates of representation.

This can have a cumulative and negative impact on their ability to garner accountability from elected officials. This is a trend that we theorized could be reversed through community based mobilization efforts, following the historical pattern evident in the Black community, but for which our analysis finds limited support. Nevertheless, we are hesitant to make too much of these findings. Our measure of having voted is self-reported, which research demonstrates is threatened by social desirability bias. Further, this is only one of the many activities we predict through institutional contact, all of which push respondents toward more participatory, if not voting oriented, actions. While a better assessment of the impact of mobilization efforts on voter turnout would draw on validated vote records, this paper focuses on the existing effect of institutional contacts on participation more broadly. Social desirability does not likewise threaten self-reports of other types of activities like those examined in the current paper, and we remain confident in the findings presented here.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We set out to determine the effect of increased mobilization efforts, co-ethnic contact, and nonpartisan mobilization on non-White political participation. We ground our hypotheses in the acknowledgment of on-going preferential treatment given to White voters by traditional partisan institutions. Within that context, nonpartisan institutions, including civic and community organizations, provide more representative and responsive outreach for non-Whites groups. While there is speculation that nonpartisan organizations are seen as more trustworthy than partisan organizations, with their history of ignoring and vilifying minority populations, the true power held by nonpartisan organizations rests with the fact that they fill an important civic void left by partisan institutions as it pertains to non-White political mobilization. As a result, we expected that self-reported nonpartisan mobilization would have a greater influence on non-White participation than self-reported outreach by political parties and campaigns.

We first theorized that increased contact overall, and by nonpartisan organizations specifically, would have a larger impact on non-White participation. We found this to be true. While increased outreach also positively affected the rate of White political participation (increasing the predicted participation average by .14) the effect was stronger for Latinos (.21), Asian Americans (.48), and Blacks (.41). Our second hypothesis predicted that co-ethnic mobilization would have a stronger positive effect for non-Whites. While the literature on co-ethnic mobilization has almost exclusively examined Latino respondents, and we also explored its potential influence on Asian Americans and Black voters. We found that co-ethnic mobilization was only effective among Latino respondents. We suspect that the nature of Latino identity and community organizations surrounding the saliency of this particular identity might be driving the strong effect of civic and community institutional outreach (Beltran Reference Beltran2010; Mora Reference Mora2014). In particular, co-ethnic outreach in Latino communities may be facilitated by more cultural competency than for Asian Americans, or an underlying group consciousness similar to Black linked fate. Nonetheless, our findings support existing theories regarding the importance of co-ethnic contact for Latinos, though they do not support an extension of co-ethnic mobilization theory to other racial groups.

Lastly, we argued that nonpartisan organizations would be more effective in mobilizing Latino and Asian American potential voters, whereas partisan organizations would be just as, if not more, effective than nonpartisan organizations in mobilizing Blacks. Our findings supported both sub-hypotheses. Self-reported nonpartisan contact had a greater impact on Latino and Asian American participation levels (.36 and .69, respectively) than self-reported partisan contact (.28 and .42, respectively). In contrast, partisan contact had a significantly higher impact on Black participation levels (.79) than did nonpartisan contact (.45). Importantly, we found that neither partisan nor nonpartisan contact had any effect on White participation levels, illustrating that persistent organizational outreach is important and consequential for racially differential participation. Put simply, “the problem…is not a political deficiency of people of color, but rather a political deficiency of current campaign outreach efforts” (Barreto Reference Barreto2018, 186–87).

We deliberately constructed a political participation scale that included both traditional forms of participation (e.g. voting), as well as informal modes (such as attending a protest) to avoid excluding less traditional political acts. Yet, we also recognize that it is important to identify which acts are increased through mobilization efforts since some activities—such as donating to a campaign or voting—have more direct political implications. To that end we re-ran each of our models predicting the impact of intensity, co-ethnic contact, and partisan versus nonpartisan contact on each of the individual participation variables that make up our index. We found few consistent patterns across racial groups. We did find that no form of contact or mobilization was associated with increased voter turnout. This finding runs counter to our expectations based in the Black participation literature, where a long history of nonpartisan community mobilizing produced higher rates of voter turnout, representation, and attention from traditional partisan organizations.

It is possible that the success of Black political standing was the result of a long period of mobilization and a deep understanding regarding the necessity of participation due to the experiences with slavery, segregation, and Jim Crow. Perhaps because other communities of color do not have the same motivation for participation, lacking extreme histories of ongoing political oppression. Another possible explanation is the lack of cohesion within Latino and Asian American communities that deal with immigration patterns from a multitude of countries that may or may not share language, religion, or other important traditions to tie them together, which would complicate the efforts of nonpartisan mobilization campaigns. It may be that the findings on voting are an artifact of methodology. The measure of voter turnout used here is self-reported. While we are confident in our overall findings, in order to assess the differential impact of mobilization efforts by formal institutions relative to informal, community based ones on voter turnout, scholars should draw on administrative records of vote history. This is an avenue for future research.

We have offered a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between mobilization efforts undertaken by partisan and nonpartisan institutions and participatory outcomes among Whites, Blacks, Latinos and Asian Americans. We derived testable implications from our theoretical propositions and leveraged the CMPS to evaluate our hypotheses. However, while the findings offered here are supportive of our theory of racialized institutional contact overall, they are correlational in nature. As such, future research should subject our theory to more rigorous causal analysis in the form of field experiments. Such research would greatly add to the work of previous scholars who used experiments to tease out why certain types of mobilizations succeed or fail to activate hard-to-reach and low-propensity voters. One consistent conclusion is that ethnic targeted mobilization efforts (and some specified, from nonpartisan institutions) do elevate turnout of unlikely voters (Abrajano and Panagapolous Reference Abrajano and Panagopoulos2011; Garcia-Bedolla and Michelson Reference Garcia-Bedolla and Michelson2012; Reference Garcia-Bedolla and Michelson2014; Ramirez Reference Ramirez2005; Reference Ramirez2007; Wong Reference Wong2005). Future work will build on these findings, honing in on the impact of nonpartisan mobilization on voter registration and turnout.

We contribute to the participation literature by parsing out the importance of mobilization for communities of color: while being asked matters, who does the asking—from an institutional perspective—has a differential impact across racial subgroups. We demonstrate that it is not only important to ask, but that the ones asking must also provide a representative or at least responsive dynamic to non-White communities. Such considerations become more salient as an increasingly diverse polity challenges the homogeneity of the American electorate, but only if that diverse electorate participates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jaime Dominguez, Luis Fraga, Ricardo Ramirez, and our other anonymous reviewers for the helpful feedback on this version of the paper. We also thank the audience from the annual American Political Science Association meeting at Philadelphia, PA 2016. We alone are responsible for the content.