Introduction

Incumbents in democratic polities have many incentives not to champion the retrenchment of large and popular social programs. Nevertheless, they often do and, in fact, even succeed in doing so. Why? Under what conditions do incumbents succeed in their attempts to impose welfare losses on large numbers of low-income voters? This paper demonstrates that policy design creates opportunities for incumbents to curtail electorally successful programs. We argue that concentration of authority in the executive offers room for blame avoidance and short-term retrenchment. By concentration of authority, we mean the executive’s power to make unilateral decisions about entitlements and benefits without having to seek approval in other arenas.

It is a matter of fact that both developed and underdeveloped welfare states face strong pressure for fiscal adjustment (Amable et al. Reference Amable, Gatti and Schumacher2006; Campello Reference Campello2015; Goldfajn et al. Reference Goldfajn, Martínez and Valdés2021; Ocampo Reference Ocampo2004; Pierson Reference Pierson and Pierson2001; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2017; Samuels Reference Samuels2003), even though central and peripheral economies are affected differently by the risk of capital outflows (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1978). As a result, incumbents in democratic polities must reconcile two key goals: good fiscal behavior must be visible, while policy retrenchment must be hidden. Under such conditions, proponents of cutbacks are expected to engage in blame-avoidance strategies to avoid electoral backlash (Hinterleitner and Sager Reference Hinterleitner, Sager, Careja, Emmenegger and Giger2020; Pierson Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996; Weaver Reference Weaver1986).

Jacob Hacker argued that the most pervasive mechanism for blame avoidance in the USA since the 1970s has been policy drift – the failure to revise policies when changes in the socioeconomic context undermine their operation or effectiveness (Béland et al. Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2016; Hacker Reference Hacker2004, Reference Hacker, Streeck and Thelen2005; Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015). However, such failure can result from different decision-making processes: policy stability can either be the result of incumbent action (executive-driven drift) or of the veto power of welfare opponents (opposition-driven drift). This paper claims that the concept of drift has been used to describe rather distinct political processes, creating an ambiguity that the literature should address to avoid labeling all outcomes of policy stability under a single broad umbrella. Our first goal is to contribute to the literature on policy drift by conceptually distinguishing executive-driven drift from opposition-driven drift and demonstrating the usefulness of this distinction.

Second, we provide empirical evidence that incumbents not only choose to retrench large and popular social policies – an unexpected strategy according to theories that emphasize the resilience of policies that directly deliver benefits to large numbers of voters (Pierson Reference Pierson1996) – but may also be successful when undertaking such initiatives. We argue that such success is explained by policy decision-making rules. Regardless of the type of program or its size (clientele or budget) and of the ideology of the incumbent, social policies that concentrate authority in the executive to set eligibility rules, benefit levels, and updates are more vulnerable to cutbacks (in absolute and/or relative terms). In other words, executive-driven drift is largely facilitated by concentration of authority because it makes blame avoidance easier. Our finding does not confirm Pierson’s (Reference Pierson1996) argument that concentration of authority increases accountability, thus creating incentives for incumbents not to retrench large and popular social programs to avoid blame. Instead, we show that concentration of authority can facilitate hidden retrenchment.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to explain why a given policy is designed to concentrate or disperse authority. Rather, we aim to demonstrate that, under conditions of concentration of authority, retrenchment by blame avoidance (Weaver Reference Weaver1988) is not only attractive but also more successful than overt changes to policies whose decision-making rules entail veto points in other arenas. As a result, some highly popular policies that benefit many low-income voters can be successfully retrenched while other less popular policies benefiting fewer low-income voters may be preserved if the decision-making rules of the former impose comparatively lower political costs on incumbents. Thus, we contribute to the literature on policy retrenchment by showing that concentration of authority provides incumbents with the means to conceal retrenchment. Our claim is that programs that grant more discretion to the executive to make decisions about entitlements and benefits facilitate less conspicuous cuts, that is, facilitate executive-driven drift.

We studied policy retrenchment initiatives in an emerging economy marked by a large prior expansion of social protection and by increasing pressure for fiscal adjustment. Brazil is a developing country under constant pressure to adopt austerity measures (Fraga Reference Fraga2004; Goldfajn et al. Reference Goldfajn, Martínez and Valdés2021; Ocampo Reference Ocampo2004). The transition to democracy in the 1980s triggered a massive increase in social spending, and both center-right and left-wing governments have enacted policies to promote the inclusion of impoverished “outsiders,” creating a large clientele dependent on public transfers (Arretche Reference Arretche2018; Holland and Schneider Reference Holland and Schneider2017). The tax burden rose to levels comparable to those of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries (Afonso and Castro Reference Afonso and Castro2016). By 2015, however, declining commodity prices, macroeconomic mismanagement, and the revelation of massive corruption schemes triggered an economic and political meltdown. The fiscal deficit exploded, and the contractionary measures started by leftist President Dilma Rousseff gained traction after her controversial impeachment. Vice President Michel Temer took power with the support of a right-wing coalition, and the election of candidate Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 shifted the presidency further to the right. Meanwhile, real GDP per capita fell by 8% between 2014 and 2016 as unemployment, poverty, and inequality rose (Barbosa Reference Barbosa2019; Barbosa et al. Reference Barbosa, Souza and Soares2020; Ciaschi et al. Reference Ciaschi, Costa, Rubião, Paffhausen and Sousa2020). In sum, Brazil showcases the rise and fall of expansionary social policy in a compressed timescale amid high levels of poverty and inequality.

We examine the evolution of the four largest federal transfer schemes in Brazil between 2010 and 2019 – the Bolsa Família program, unemployment insurance benefits, the Continuous Cash Benefit (BPC), and minimum wage pensions. Since these are all popular social policies that have been subjected to retrenchment efforts by incumbents, we were able to conduct a policy-focused analysis by examining the influence of fiscal impact, beneficiary power, decision rules, and incumbent partisanship (independent variables) on the outcome of retrenchment initiatives (dependent variable). Our intervening variable is the concentration of authority in the executive branch. Our research design controls for the role of the polity (a presidential federation), policy type (monetary transfers), and clientele profile (low-income and poorly organized recipients) – with no variation across cases. We also chose not to include the Covid-19 period because it generated exceptionally high domestic pressure to increase social expenditures.

We found significant variation in the fate of the four policies subjected to retrenchment initiatives: two of them (BPC and minimum wage pensions) were not only largely untouched, but had their spending increased, while the other two (Bolsa Família and unemployment insurance benefits) were effectively curtailed. Our study provides strong support for our theoretical proposition: programs granting more discretion to the executive were retrenched, regardless of fiscal impact, size of the clientele, and partisanship of the incumbent. While the expansion of social spending creates large constituencies, it also raises concerns in emerging economies about fiscal sustainability and leads to credible risk of capital outflow on a scale unknown to central economies. In these cases, incumbents need to signal that they are moving toward austerity.

Table 1 summarizes the main features of our programs. Columns (A) and (B) report each program’s clientele size and budget. Column (C) describes their main constituencies. Middle-class workers may receive unemployment insurance benefits but are ineligible for the other three programs; also, unemployment claims by low-wage workers far outnumber those made by middle-class professionals (Teixeira and Balbinotto Neto Reference Teixeira and Balbinotto Neto2014). Column (D) ranks the level of discretion granted to the executive. Column (E) informs the mechanism that we argue explains the outcome displayed in column (F).

Table 1. Selected features of the largest federal transfer schemes

Source: authors’ elaboration.

Notes: columns (A) and (B) report averages over 2010–2019.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. “Policy drift revisited: executive-driven versus opposition-driven” develops the distinction between executive-driven and opposition-driven policy drift. “Theories and expected outcomes” reviews the main factors advanced in the literature to explain why some programs are more vulnerable to retrenchment than others, and places in context our hypothesis regarding the concentration of authority in the executive as a facilitator of policy drift. “Research design and case selection” explains the rationale for our research design. “The rise and decline of expansionary social policy in Brazil” provides an overview of the evolution of social spending in Brazil. “Programmatic retrenchment by executive-driven drift” and “Resilience in troubled times: minimum wage pensions and BPC” examine why Bolsa Família and unemployment insurance benefits were successfully retrenched while minimum wage pensions and the BPC proved more resilient.

Policy drift revisited: executive-driven versus opposition-driven

Drift is a hidden mechanism of policy retrenchment (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015, p. 198). The mainstream application of the concept defines it as policy stability in the face of increasing needs. Policy drift occurs when political agents are aware of these shifts in needs but fail to update existing rules despite the availability of alternatives that could remedy them, resulting in de facto retrenchment in either absolute terms or relative to needs (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010; Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015). The concept does not specify who the political actors might be, or the timescale involved, though research centered on the USA has stressed the role of organized interests and Republican legislators as leading veto actors (Béland et al. Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2016; Hacker Reference Hacker2004, Reference Hacker, Streeck and Thelen2005; Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015).

This current usage is too broad. The political conditions necessary for successful drift vary widely, whether policy stability (or downscaling) results from actions undertaken by the incumbent or from minority efforts to veto policy changes. Thus, it is conceptually possible and analytically helpful to distinguish between executive-driven and opposition-driven drift. The former results from the incumbent’s decision; the latter corresponds to successful efforts by organized minorities to block proposals to update or expand social protection. We argue that the former is facilitated by concentration of authority, while the latter is facilitated by its dispersion.

Health policy in the USA is a case in point. Hacker’s (Reference Hacker2004) analysis of the “formidable constellation of ideologically committed opponents and vested interests” that blocked policy change in the twentieth century depicts opposition-driven drift. In turn, the follow-up study by Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2016) on the implementation of the Affordable Care Act documents how executive-driven drift by Republican governors undermined coverage (see also Jacobs and Mettler Reference Jacobs and Mettler2018).

Opposition-driven drift can indeed occur when “political polarization is higher, institutional veto points are more numerous and more binding, and provisions for automatic revisions updating are weaker” (Galvin and Hacker Reference Galvin and Hacker2020, p. 4). Even if the incumbent wants to act, the likelihood of success is low because of asymmetries inherent in the rules of the game: the incumbent must garner support to overcome multiple institutional hurdles, while opponents can block change even when outnumbered. In such cases, the responsibility for policy stability rests with the opposition. Incumbents may be blamed for “not getting things done,” but they may legitimately try to deflect criticism. Electoral punishment may target the opposition, although informational constraints make this unlikely (Giger Reference Giger2012).

Executive-driven drift is a different process: policy stability or downscaling is the preference of incumbents. They do not seek to update policy, so their decisions cannot be vetoed by welfare opponents. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine the political motivations behind incumbents’ decisions to engage in policy drift, we argue that the discretion provided by policy-specific decision-making rules makes executive-driven drift more likely to succeed than attempts to obtain the consent of key actors across multiple political arenas to enact overt cutbacks.

Executive-driven drift is a blame avoidance rather than a credit-claiming strategy. Incumbents may gain popularity by curbing social programs when backed by large constituencies with pro-retrenchment preferences (Giger Reference Giger2012; Giger and Nelson Reference Giger and Nelson2013; Nelson Reference Nelson2016). These are cases of successful retrenchment supported by conservative voters. Instead, executive-driven drift occurs when the incumbent wants to cut spending but either cannot get majority support for overt reform of existing programs or fears electoral punishment. Thus, retrenchment by executive-driven drift happens when the incumbent deliberately fails to update policy parameters despite growing needs, that is, when the incumbent’s deliberate decision to maintain existing policy rules leads to policy retrenchment.

The potential for successful executive-driven drift varies across policies because it depends on the degree of executive discretion over key policy parameters. Open-ended entitlements, fully indexed programs, and policies tightly regulated by statutory prescriptions are more resilient, as legislative and judicial oversight constrain executive discretion. The same applies to well-designed automatic stabilizers. Conversely, executive-driven drift is more successful with policies that: (a) are not indexed, particularly if rules specify nominal values; (b) do not have statutory provisions anchoring them to credible indicators of social welfare; (c) have built-in expiration dates; (d) are not set up as open-ended entitlements; and (e) cannot be readily defended in court by their advocates. Under such rules, delegation of authority to the executive is broad. If the executive can unilaterally make decisions about entitlements and benefits, freezing or downscaling them in face of mounting needs can be a successful covert strategy.

The concept of executive-driven drift is useful for explaining why and how large and highly popular programs are successfully curtailed in a direction not predicted by arguments stressing the role of fiscal impact, beneficiary power, or incumbent partisanship. The next section details alternative theories and their expected outcomes.

Theories and expected outcomes

In this paper, we argue that the concentration of authority facilitates executive-driven policy drift, thereby greatly increasing the probability of success of retrenchment initiatives. However, there are several alternative approaches to explaining what makes some social programs more (or less) vulnerable to retrenchment. In this section, we review four major types of explanations and how their predicted outcomes relate to our findings. We also discuss how our hypotheses fit with prevailing theories.

Fiscal impact

Fiscal deficits and rising public debt are powerful drivers behind cutbacks (Amable et al. Reference Amable, Gatti and Schumacher2006; Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi Reference Korpi2003; Pierson Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996, Reference Pierson and Pierson2001; Weaver Reference Weaver1986, Reference Weaver1988). The need to reduce deficits can force unwilling governments to embrace austerity (Campello Reference Campello2015; Levy Reference Levy2001), or it might simply provide political cover for ideologically motivated politicians. By this reasoning, politicians would have strong incentives to pursue austerity by targeting the most expensive programs first. Trajectory matters too: programs with ballooning budgets should also be prime candidates for freezes and cutbacks. The logic holds even if retrenchment is ideologically driven; cutting small programs is hardly a significant step toward small government (Pierson Reference Pierson1994, p. 102).

We do not deny that fiscal deficits can indeed be a primary motivation for retrenchment, and in fact the pressure for fiscal austerity underpins the four retrenchment initiatives we selected. Yet, according to this argument, we would expect incumbents to devote all available political resources to reforming minimum wage pensions, which account for more than 60% of the combined spending on all four programs (Table 1) – a percentage that is on the rise due to population ageing. Meanwhile, the fiscal argument dictates that relatively inexpensive programs should be preserved because the fiscal payoff would not be worth the political cost.

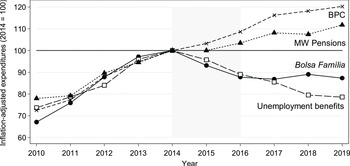

These predictions did not come true in Brazil. As we will show, Bolsa Família and unemployment insurance benefits were subjected to extensive retrenchment despite having much smaller annual budgets than the BPC and minimum wage pensions (Table 1 and Fig. 1). De-indexation of pensions and the BPC from the minimum wage has been openly discussed in the political arena as an effective solution to the fiscal deficit, and many social security reform proposals have included some version thereof. However, all attempts have failed to gain approval, and pension-related spending has continued to rise (Fig. 1). While the fiscal deficit can be a primary motivation for retrenchment initiatives, it is clearly not a sufficient condition for successful programmatic retrenchment.

Figure 1. Inflation-adjusted expenditures on federal transfers (2014 = 100).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Anuário Estatístico da Previdência Social, SAGI/Vis Data, and MTE, Programa de Disseminação de Estatísticas do Trabalho.

Note: Data points express inflation-adjusted expenditures relative to the benchmark year of 2014.

Recipients’ power resources

The standard assumption is that retrenchment is unpopular and that the threat of electoral punishment haunts the minds of politicians (Pierson Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson1996). Power resource theories predict that rational officeholders would then prefer to target policies with weaker constituencies. Thus, clientele size figures prominently in attempts to explain why some programs are more vulnerable than others. Korpi and Palme’s (Reference Korpi and Palme1998) “paradox of redistribution” asserts that narrowly targeted means-tested programs are less resilient and less effective at reducing inequality than more universalistic policies, and even critics who dispute the link between universalism and resilience concede that “the weakness of means-tested programs is already reflected in their size” (Pierson Reference Pierson1994, p. 6). Larger programs should be more resilient than targeted policies because of the number of recipients and the potential for electoral punishment they represent.

Political clout depends not only on size, but also on the ability of recipients to voice their concerns and engage in effective collective action. Programs targeting the poor are said to be more vulnerable to cuts because they benefit a small group with limited mobilization capacity and alienate the middle class (Bonoli Reference Bonoli, Armingeon and Bonoli2007; Hacker Reference Hacker2004; Korpi Reference Korpi2003; Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998; van Vliet and Wang Reference van Vliet and Wang2019). Low-income recipients also tend to have lower voter turnout, which translates into reduced capacity to inflict punishment by retrospective voting (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Rueda Reference Rueda2005).

Should the argument about clientele size fully explain outcomes, we would expect large, popular policies to be preserved because incumbents would prefer to avoid the blame of imposing losses on concentrated categories of beneficiaries. Or, alternatively, if they dared to do so, they would not be able to muster enough support in the parliamentary arena.

Our study does not confirm the first expectation, as incumbents do take initiatives to retrench policies that benefit millions of beneficiaries. The second prediction is closer to our results: it is indeed extremely difficult to muster a large number of voters to win approval for retrenchment initiatives when large constituencies are involved. However, this is only a partial confirmation, since the Bolsa Família program – once described as the most effective strategy for winning elections in Brazil (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007) – suffered significant cuts in real terms while the BPC, with a much smaller clientele, survived untouched. Some intervening factor is missing. Electoral stickiness (Pierson Reference Pierson and Pierson2001) does not fully explain the politics of retrenchment.

Incumbents’ partisanship

Retrenchment is not just about avoiding blame. Incumbents always have some room to advance their own ideological preferences. Party ideology may also lead incumbents to impose austerity on the opposition’s constituency rather than on their own supporters. Levy (Reference Levy1999, Reference Levy2001) argued that right-wing parties tend to push regressive reforms as far as they can, while left-wing parties try to turn “vice into virtue” by “targeting inequities in the welfare system that are simultaneously a source of inefficiency” (Levy Reference Levy1999, p. 265). According to this view, right-wing coalitions should pursue across-the-board retrenchment more aggressively (Amable et al. Reference Amable, Gatti and Schumacher2006), and programs favoring the disadvantaged should be at greater risk. Conversely, left-wing retrenchment targets regressive policies that are costly or inefficient and do not benefit left-wing “insiders” (Rueda, Reference Rueda2005).

In Brazil, the impeachment of leftist President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 shifted power to a right-wing coalition. Should the partisan argument fully explain retrenchment outcomes, we would expect the Bolsa Família program to be protected under Rousseff, given its importance to her own party’s electoral performance (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007). In addition, we would expect Rousseff not to curtail unemployment insurance benefits to formal wage workers, a constituency of left-wing parties. Finally, we would see more drastic retrenchment outcomes in all programs after 2016.

The partisan argument does not hold. As discussed below, public spending on Bolsa Família transfers and unemployment insurance benefits reversed course during the Rousseff administration (Fig. 1). Retrenchment outcomes did not worsen after the 2016 impeachment; nor did they become more pervasive.

Policy design

The policy-focused approach underscores the importance of program design (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014). A fundamental insight is that formal revision of rules at critical junctures is not the only form of institutional transformation, as gradual change can also unfold through less visible mechanisms such as layering, conversion, and drift. The argument is that policy rules constrain the choices of welfare state advocates and their opponents as they struggle to reshape existing policies (Béland et al. Reference Béland, Rocco and Waddan2016; Galvin and Hacker Reference Galvin and Hacker2020; Hacker Reference Hacker2004, Reference Hacker, Streeck and Thelen2005; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014; Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Pierson, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2015; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010). Most studies have examined how policy features influence the choices of political actors, whereas research on criteria for ranking social programs according to their vulnerability to successful retrenchment – our central concern – is scarcer.

Our contribution is to refine the concept of drift to highlight how a crucial aspect of policy design – concentration of authority – plays a central role in explaining retrenchment outcomes. In doing so, we challenge the influential view that concentration of authority actually reduces the likelihood of retrenchment by increasing accountability (Pierson Reference Pierson1996). Our alternative hypothesis is that greater capacity to make unilateral policy decisions raises the likelihood of retrenchment outcomes by allowing incumbents to hide benefit reductions.

Research design and case selection

We are interested in the outcomes of incumbents’ retrenchment initiatives. Following our definition of executive-driven drift, we selected cases in which two conditions were present: (i) a context of rising needs and (ii) the decision of incumbents to retrench social policy. Conversely, examining opposition-driven drift would require (i) the executive’s decision to expand policies and (ii) its defeat by welfare opponents. A large body of literature, especially on veto points (Galvin and Hacker Reference Galvin and Hacker2020; Immergut Reference Immergut1990), has made important contributions to this topic. Our contribution is to focus on the mechanisms that affect the success of incumbents’ retrenchment efforts. We can say that executive-driven drift occurs when incumbents succeed in de facto downscaling policies by deliberately maintaining the same formal rules under changing circumstances ultimately compromising policy outcomes.

We tracked the evolution of the four largest federal transfer programs in Brazil between 2010 and 2019. All of them were subjected to the incumbents’ revealed preference for retrenchment, but in only two of them was the executive successful.

The explanatory factors we examine are fiscal impact, clientele size, incumbents’ partisanship, and the degree of discretion the incumbents have when making policy decisions. Our four executive-driven retrenchment initiatives display different combinations of attributes: (i) one case combining small clientele size and low discretion (BPC); (ii) a case combining large clientele size and low discretion (minimum wage pensions); (iii) a case combining large clientele size and high discretion (Bolsa Família); and (iv) a case combining small clientele size and moderate discretion (unemployment insurance benefits). Although they differ in relevant dimensions, we selected policies with different pairs of combinations of our explanatory factors. We also controlled for the role of the polity (a presidential federation), the type of policy (distributive cash transfers), and clientele profile (low-income and poorly organized recipients).

The rise and decline of expansionary social policy in Brazil

The “Citizen Constitution” of 1988 laid the foundations of a European-inspired welfare state by expanding entitlements in key social areas (Arretche Reference Arretche2018; Lobato Reference Lobato2009). The trend began under the center-right government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1994–2002) and accelerated under the center-left Workers’ Party administrations (Arretche Reference Arretche2018; Hunter Reference Hunter2014; Power Reference Power2010). Lula da Silva (2003–2010) and his successor, Dilma Rousseff (2011–2016), increased social spending as the commodity boom of the 2000s and the return of economic growth eased fiscal constraints (Campello Reference Campello2015; Gobetti and Orair Reference Gobetti and Orair2015). Neither attempted radical redistribution, and social spending was financed by increasing revenues from a regressive tax system (Fandiño and Kerstenetzky Reference Fandiño and Kerstenetzky2019; Gobetti and Orair Reference Gobetti and Orair2017), as in most of Latin America (Holland and Schneider Reference Holland and Schneider2017). Social spending by the federal government climbed from 11.2% of GDP in 1995 to 13.8% in 2005 and to 17% in 2014 (STN 2016a; Castro et al. Reference Castro, Ribeiro, Chaves and Duarte2012).

Brazil’s fortunes changed rapidly in the mid-2010s. The 2014–16 recession was the worst on record: GDP fell by 7%, inflation briefly spiked to double digits, and the federal primary balance plummeted. Unemployment soared from a record low of 6.2% in late 2013 to 13.7% in early 2017, and wage inequality surged (Barbosa Reference Barbosa2019; Ciaschi et al. Reference Ciaschi, Costa, Rubião, Paffhausen and Sousa2020). Poverty and unemployment rates rose during the recession: Brazil was the worst performing Latin American country in the mid-2010s (Ciaschi et al. Reference Ciaschi, Costa, Rubião, Paffhausen and Sousa2020) despite having four large and popular cash transfer programs for low-income recipients.

Faced with strong fiscal pressure, every president from Dilma Rousseff to Jair Bolsonaro took initiatives to curb public spending, yet outcomes differed from the predictions outlined in “Theories and expected outcomes”. Figure 1 shows divergence in social spending across programs by plotting inflation-adjusted expenditures relative to 2014. Before the recession, all programs grew in real terms, with Bolsa Família leading the way with a 50% increase in transfers between 2010 and 2014. The recession introduced a sharp bifurcation. Minimum wage pensions and BPC kept pace, but Bolsa Família and unemployment insurance benefits declined even as poverty and unemployment increased. Neither recovered. By 2019, federal spending on both had fallen back to 2011–12 levels, while real disbursements for minimum wage pensions and BPC grew almost 50% over the decade. The divergence becomes even more striking when one considers the increase in social risks brought on by the recession.

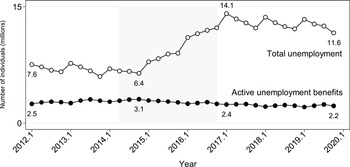

Table 2 breaks down the variation in total real program spending between 2014 and 2019 into two components: changes in the number of benefits and changes in the average real benefit value. Retrenchment mechanisms varied across programs. On the one hand, Bolsa Família transfers dropped by nearly 19% in real terms, a decline that is almost entirely explained by a decrease in average benefits. On the other hand, spending on unemployment insurance benefits fell by 29% due to reduced coverage, with average benefits even increasing slightly. Outlays on minimum wage pensions and the BPC grew by 15% and 28%, respectively, with both components making positive contributions, despite a more significant increase in the number of benefits.

Table 2. Decomposition of relative changes in real expenditures into changes in the number of benefits and changes in average real benefit values (% of total spending in 2014) – Brazil, 2014 vs. 2019

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The fiscal impact hypothesis does not explain this pattern. If retrenchment outcomes were driven by fiscal consolidation, minimum wage pensions would have been sacrificed. The deficit reduction potential of the other three programs was minimal by comparison. Nor was the size of those programs critical. If the number of beneficiaries actually had such an overwhelming influence on policy choices, the Bolsa Família program would have been spared along with minimum wage pensions. Instead, the BPC – a smaller but more expensive program – saw the largest increase in spending. Finally, the predictions of the partisanship argument also failed to materialize.

Under high inflation, President Dilma Rousseff managed to curb real public spending on policies that protected her own party’s constituency, and the rightward shift of the ruling coalition after her impeachment in 2016 did not lead to visible changes in either the pattern or the scale of programmatic retrenchment.

We argue that these results can be better understood by taking into account the degree of unilateral decision-making that each policy provided to the executive. From Rousseff onwards, incumbents were successful when they were able to adopt executive-driven drift as a strategy. In short, policy design played a key role in the fate of these policies. Incumbents failed to cut spending when they had to overcome veto points in other political and judicial arenas, yet succeeded when they had the authority to make unilateral decisions on programs.

Programmatic retrenchment by executive-driven drift

The Bolsa Família program

The Lula da Silva administration launched Bolsa Família in 2003 to consolidate a patchwork of targeted cash transfers created by former President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. The program provided monthly cash transfers to low-income families, especially those with children, who in turn had to comply with health and education conditionalities (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2014; Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Cotta, Barrientos, Compton and Hart2019).

The Bolsa Família program expanded coverage and quickly became Brazil’s flagship anti-poverty initiative. The new program won over experts and voters for its targeting accuracy and role in reducing poverty, and was praised for its technocratic management, decentralized implementation, and shunning of traditional clientelist practices (Barros et al. Reference Barros, Carvalho, Franco, Barros, Foguel and Ulyssea2007; Fenwick Reference Fenwick2009; Fried Reference Fried2012; Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007; Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2014; Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Cotta, Barrientos, Compton and Hart2019; Soares et al. Reference Soares, Osorio, Soares, Medeiros and Zepeda2009; Souza et al. Reference Souza, Osorio, Paiva and Soares2019).

Bolsa Família was the largest conditional cash transfer program in the world in absolute terms in the early 2010s (World Bank 2015, pp. 12–14). Between 2004 and 2014, the number of Bolsa Família recipients rose from 3.6 million to 14 million households, or 20%–25% of the population. Average monthly benefits were always meager, peaking at $89 per household in 2014 (in 2017 international dollars). As a result, the program’s budget never exceeded 0.5% of GDP, or about 2% of federal budget expenditures, as is typical of innovations in the “easy stage of redistribution” (Holland and Schneider Reference Holland and Schneider2017).

The mid-2010s were a turning point, as program expansion turned into retrenchment. Contractionary reforms were never openly discussed. Rather, the program was undermined by executive-driven drift beginning as early as 2015, when the Workers’ Party was still in power. Expenditures shrank in real terms (Fig. 1) and relative to social risks, as reflected in the increased demand to participate in the program – the waiting list peaked in May 2015 at nearly two million eligible families (Souza and Bruce Reference Souza and Bruce2022, p. 17).

From Rousseff to Bolsonaro, incumbents allowed inflation to erode eligibility thresholds and benefit values. Updates to program parameters were infrequent, insufficient to compensate for inflation, and timed to meet political needs. Rousseff increased benefits six months before the 2014 presidential election. Her successor, Michel Temer, authorized a readjustment in 2016 immediately after Rousseff’s impeachment and again just before the 2018 election. For the most part, benefits and eligibility thresholds remained frozen in nominal terms. Consequently, by early 2020 the real average monthly benefit was 15%–20% lower than at its peak in 2014. The decline in eligibility thresholds was even more pronounced. On the eve of the Covid-19 pandemic, both poverty lines used to target benefits were at their lowest levels ever, and the lower eligibility threshold was then 40%–45% below the international benchmark of $2.15 per day (in 2017 international dollars). These trends were not offset by an expansion in the number of beneficiaries. On the contrary, the national coverage target of 14 million households was not updated after 2012, despite rising poverty, while actual coverage dipped below this figure on more than one occasion.

Retrenchment occurred by force of executive-driven drift. The Bolsa Família legislation gave the executive discretion to regulate most aspects of the program through non-statutory decrees. The program was not an open-ended entitlement and lacked constitutional safeguards. Benefits were not automatically granted to families who met the eligibility criteria. The annual budget approved for the program was binding, and new benefits were issued only when recipient households (voluntarily or not) left the program, or when additional funds were appropriated. Otherwise, families were placed on a waiting list. Eligibility thresholds and benefits were not indexed to inflation, and adjustments were entirely at the incumbent’s discretion. Similarly, the executive had full authority over the national coverage target, which was not anchored to objective poverty indicators, while executive agencies were free to determine how often families had to recertify their registration information and how stringent means-testing verification procedures should be. Beneficiaries and applicants had no legal recourse to challenge administrative decisions, except in extremely rare cases.

Executive-driven drift proved more successful than overt downsizing. In 2017, the Temer administration enforced a draconian means-testing verification process and abruptly purged one million households from the Bolsa Família program; however, the rollback was short-lived due to media backlash. More recently, budget shortfalls halted the granting of benefits and made the number of beneficiaries drop by 1.1 million households in seven months. Again, media attention put the government in the spotlight, and coverage was restored to previous levels in early 2020.

Unemployment insurance benefits

Unemployment insurance benefits were enshrined in the 1988 Constitution as a social right of formal workers dismissed without just cause (Ramos Reference Ramos2021). Workers in the informal sector, who make up about 40%–45% of the labor force, remain largely ineligible for benefits. Even so, on average, unemployment recipients are hardly affluent – they are typically young, unskilled, low-wage urban workers with low job security (Teixeira and Balbinotto Neto Reference Teixeira and Balbinotto Neto2014).

Claimants must meet minimum job tenure requirements, and benefit duration ranges from three to five months, depending on job tenure. Benefits are weakly earnings-related, limited from below by the minimum wage and from above by a benefit cap that has not exceeded 200% of the minimum wage floor since 1995. Benefits are automatically updated in line with the minimum wage and inflation.

Unemployment benefits are the quintessential automatic stabilizer. In Brazil, however, high job turnover rates and the unemployment insurance program’s well-known formal sector bias produce counterintuitive results. Benefits and spending are procyclical because prolonged downturns increase long-term unemployment and shrink the formal labor market. Consequently, workers have a harder time meeting eligibility criteria. Conversely, economic growth leads to program expansion following job creation in the formal sector (Pires and Lima Jr Reference Pires and Lima2014; Santos Reference Santos2019). In addition, the federal government tends to raise the minimum wage more aggressively during expansions.

In the aftermath of the 2008–09 global financial crisis, President Lula advocated countercyclical measures and pushed for an extension of unemployment insurance benefits. Business and labor leaders acquiesced, and benefits were temporarily extended by two months for workers in the hardest-hit sectors. During the mid-2010s recession, no such measure was enacted: faced with greater budgetary pressure, incumbents stood pat as unemployment rose.

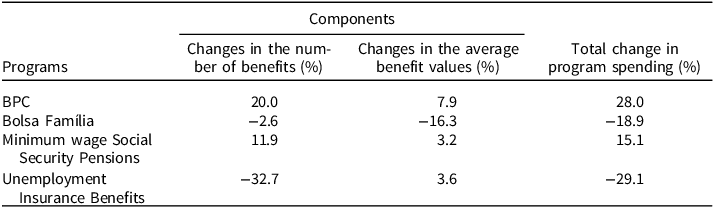

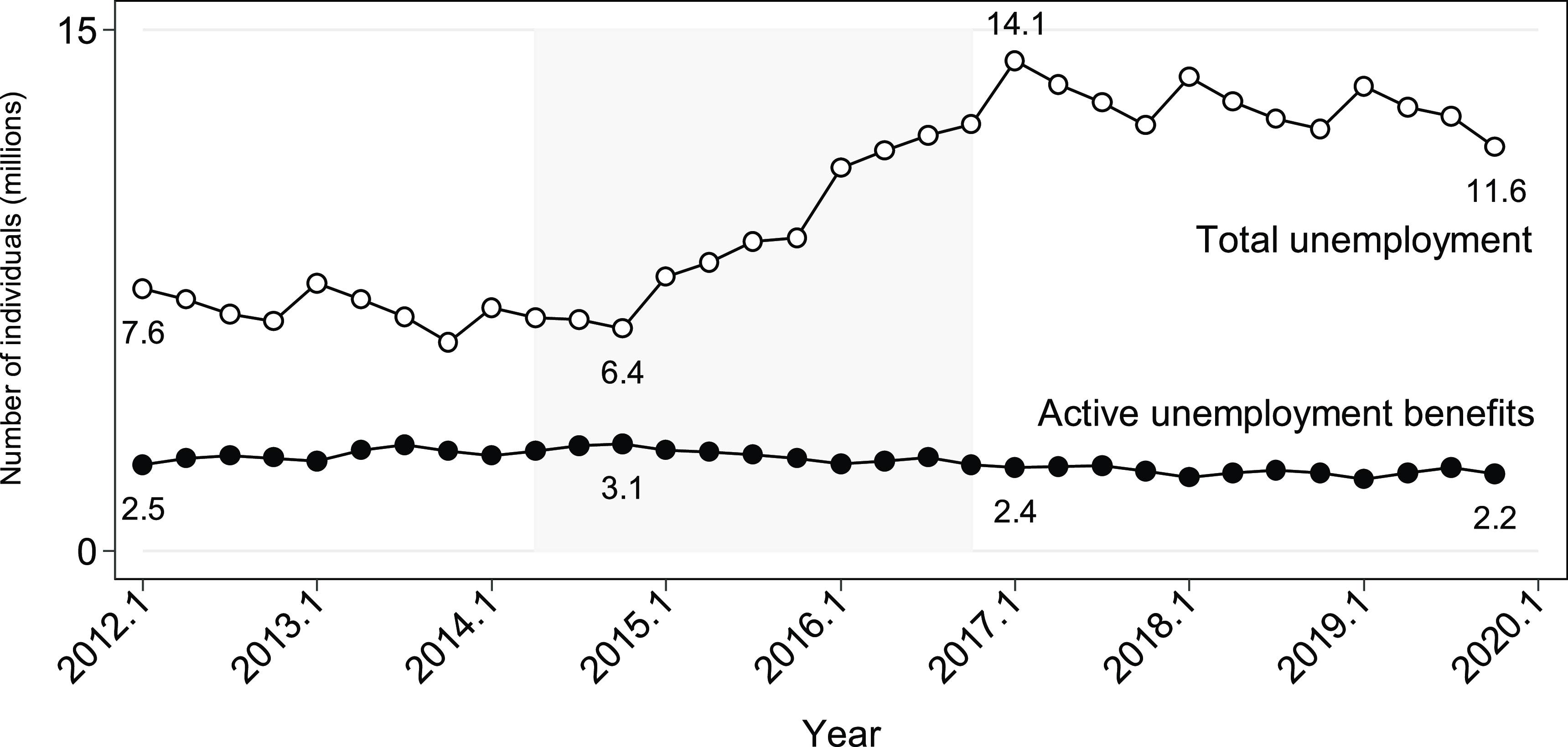

Figure 2 shows total unemployment data from quarterly surveys and the official number of active unemployment insurance benefits, a reasonable proxy for coverage. Unemployment insurance did not respond to the economic crisis. Retrenchment was not just a matter of stability in the face of rising social risks. The size of the program expanded during the good times (2012–14) and then contracted by more than 20% in the wake of the downturn (Pires and Lima Jr Reference Pires and Lima2014; Santos Reference Santos2019; STN 2016b). Since then, the number of beneficiaries has never recovered despite higher unemployment.

Figure 2. Total unemployment and active unemployment benefits (millions).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on PNADC microdata and CAGED Estatístico series.

In contrast to Bolsa Família, average unemployment insurance benefits did not suffer losses due to inflation (Table 2). Executive discretion over unemployment insurance benefits is not as extensive as in the case of Bolsa Família, but it is still substantial. Brazilian presidents can enact reforms through administrative decrees that require simple majorities for approval in both houses of Congress, while presidents hold veto power over congressional decisions.

This process played out in December 2014, when President Dilma Rousseff signed an administrative decree (Provisional Measure 665/2014) imposing stricter job tenure requirements for first- and second-time claimants. Although concerns about public spending were already evident, the Workers’ Party administration argued that the new legislation was aimed at eliminating fraud and collusion between workers and employers. Rousseff’s proposal raised the minimum job tenure from six to 18 months for first-time claimants and to 12 months for second-time claimants. The minimum eligibility threshold for more recurrent claimants remained unchanged at six months. Congress significantly watered down the original proposal, and the bill signed into law in June 2015 increased the minimum tenure requirements for first- and second-time claimants to 12 and nine months, respectively (Cravo et al. Reference Cravo, O’Leary, Sierra and Veloso2020; Santos Reference Santos2019; STN 2016b). However, Rousseff vetoed part of the bill approved by Congress, which extended the benefit for formal rural workers, arguing that such extension had many legal problems that would compromise policy delivery.

The collapse of the labor market reversed a decade-long decline in informality and unemployment, while the favorable conditions that supposedly motivated the reform no longer prevailed. The labor force in the formal private sector contracted by 7% over 2014–16, as 3.5 million formal jobs disappeared. Net job creation over 2017–19 did not make up for the losses. By the end of 2019, formal private sector jobs employment was still 4% below its 2014 peak (SEPRT 2020). Unemployment insurance claims declined because millions of workers were excluded from the formal labor market, while many quit the labor force altogether (Barbosa et al. Reference Barbosa, Souza and Soares2020).

Ultimately, the decision-making rules favored an outcome closer to the incumbents’ revealed preferences. Starting in 2015, executive-driven drift curtailed the number of recipients and curbed social spending on unemployment benefits. In contrast to the 2008–09 financial crisis, benefits were not extended. No measures were taken to address the widely recognized procyclical bias in program design. Although Rousseff’s restrictive reforms required congressional approval, the need for simple majorities and the executive’s veto power over congressional bills provide room for unilateral decisions by incumbents. Neither Rousseff nor her successors rolled back the 2014–15 reforms after circumstances changed.

Resilience in troubled times: minimum wage pensions and BPC

Social security in Brazil was created in the 1920s and has undergone a long process of expansion and modernization over time, culminating in its inclusion among the social rights entrenched in the 1988 Constitution. The pension system for private sector workers is a mandatory, pay-as-you-go scheme financed by payroll taxes, employee contributions, and other sources, including contributions from the Treasury to offset shortfalls. Because of the limited size of the formal labor market, many groups of workers are heavily subsidized, notably rural workers engaged in subsistence farming or in other small-scale agricultural or extractive activities.

The 1988 Constitution established the federal statutory minimum wage as the benefit floor for Social Security pensions and delegated to the executive branch the power to set the level of the benefit cap. At a minimum, nominal benefits must be updated annually to compensate for inflation. In practice, indexing Social Security benefits to the minimum wage aligned the interests of a formidable coalition of workers and retirees, and incumbents did not miss the opportunity to claim credit. The inflation-adjusted minimum wage has more than doubled since 1995, far outpacing productivity growth (Brito et al. Reference Brito, Foguel and Kerstenetzky2017; Cechin and Cechin Reference Cechin, Cechin, Tafner and Giambiagi2007; Varsano and Mora Reference Varsano, Mora, Tafner and Giambiagi2007). This trend accelerated under the Workers’ Party. In 2007, Lula negotiated with labor unions a formula that pegged minimum wage hikes to inflation and past GDP growth rates. This formula was signed into law in 2011 under Rousseff and reauthorized in 2015, before Bolsonaro allowed it to expire in 2019. Notably, indexation to the federal minimum wage has narrowed pension differentials, as higher benefits are only adjusted for inflation: in the early 2000s, the benefit cap for private sector workers was nine times the benefit floor (the legal minimum wage); by 2019, the ratio had fallen to roughly six times.

Minimum wage benefits account for nearly two-thirds of old-age and survivors’ pensions, whereas 40% of minimum wage benefits correspond to the aforementioned “rural pensions,” which are almost indistinguishable from social assistance transfers, since special retirement rules effectively exempt subsistence agricultural workers from social security contributions (Cechin and Cechin Reference Cechin, Cechin, Tafner and Giambiagi2007; Maranhão and Vieira Filho Reference Maranhão and Vieira Filho2018). Among urban workers, minimum wage pensions are mostly paid to unskilled, low-wage individuals who meet age requirements (Costanzi and Ansiliero Reference Costanzi and Ansiliero2016). In all cases, a rapidly rising minimum wage implies that current benefits are typically much higher than past earnings for minimum wage pensioners.

The BPC is a constitutionally guaranteed, noncontributory entitlement that is also indexed to the minimum wage. It provides unconditional transfers to poor elderly and disabled persons who do not receive other Social Security benefits, thus serving as a safety net for those who do not qualify for regular pension and disability benefits (Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Britto and Soares2007).

Outlays on pensions and BPC have risen sharply since the mid-1990s. Demographic changes, the rising minimum wage, and undemanding eligibility criteria have fueled this steady expansion, resulting in large shortfalls that need to be covered by Treasury funds. Rapid population ageing raises doubts about fiscal sustainability and alarms financial markets (Cechin and Cechin Reference Cechin, Cechin, Tafner and Giambiagi2007; Costanzi et al. Reference Costanzi, Amaral, Dias, Ansiliero, Afonso, Sidone, de Negri, Araújo and Bacelette2018; Varsano and Mora Reference Varsano, Mora, Tafner and Giambiagi2007).

Economic growth dampened concerns until the looming recession of 2014–2016 revived calls for pension reform (Costanzi et al. Reference Costanzi, Amaral, Dias, Ansiliero, Afonso, Sidone, de Negri, Araújo and Bacelette2018). Economic and political elites worried about budget rigidities and fiscal deficits as open-ended entitlements and other mandatory spending increasingly crowded out other expenditures. Public spending on the pension system (including civil servants) reached 13% of GDP in 2016 – more than health and education expenditures combined (Souza et al. Reference Souza, Vaz and Paiva2021).

Incumbents faced a dilemma. Social Security pensions were an obvious target, but their legal status blocked hidden mechanisms for retrenchment, with executive-driven drift rendered unfeasible, as incumbents lacked the authority to freeze concessions and/or benefit levels. Both the BPC and minimum wage pensions are fully “automatic” entitlements (Weaver Reference Weaver1988), and constitutional safeguards allow claimants to go to court to overturn administrative decisions.

Overt reform was the only way to go. In 2016, the Temer administration introduced a radical reform proposal that, if enacted, would slash benefits in both public and private sector pension systems. Minimum wage pensions and the BPC would suffer the most severe cuts. The reform package aimed to (i) convert rural pensions into regular contributory benefits; (ii) increase the minimum contribution period required to claim benefits by ten years; (iii) raise the legal age of eligibility for BPC benefits from 65 to 70 years; and (iv) repeal the indexation of survivors’ pensions and the BPC to the minimum wage (Costanzi et al. Reference Costanzi, Amaral, Dias, Ansiliero, Afonso, Sidone, de Negri, Araújo and Bacelette2018; Souza et al. Reference Souza, Vaz and Paiva2021).

Temer’s attempt at radical retrenchment failed. Because the reform required a constitutional amendment, it had to be approved by a roll call vote of a three-fifths supermajority in both legislative chambers. The backlash was immediate, and the designated legislative committee quickly moved to exclude the most popular and controversial provisions. It was still not enough, and the reform bill languished in Congress after new corruption allegations tarnished the president and his closest associates.

Another attempt was made in 2019 after the inauguration of President Jair Bolsonaro. Again, the goal seemed to be radical retrenchment. Media reports even floated the possibility of switching to a fully funded defined contribution system based on individual accounts, building on the cases of Chile, Peru, and Colombia. In the end, radical reform did not materialize. Bolsonaro submitted a pension bill that was close to Temer’s reform watered-down version and was approved in late 2019.

Ultimately, minimum wage pensions and the BPC escaped attempts at retrenchment. None of the original goals of the reform were achieved. There were no changes to rural pensions, the minimum contribution period, the legal age of eligibility for the BPC, or the indexation of benefits to the minimum wage. Instead, the main provisions trimmed benefits for more affluent workers and set a legal retirement age to suppress early retirement, which again mostly affected middle-class workers.

Congress refused to impose losses on the poor. As shown in Fig. 1, public spending on both programs did not deviate from the trend. Social Security coverage has not faltered either. In 2019, half of the elderly population received a minimum wage pension or the BPC, while 38% received higher pension benefits.

Conclusion

The literature on the “new politics” of social protection has underestimated the role of concentration of authority. Concentration of authority was critical to the expansion of welfare policy and remains key to certain strategies of policy retrenchment. Executive-driven drift is one such strategy. Under pressure to signal good fiscal behavior, incumbents succeed by targeting policies whose decision-making rules give them discretion to make unilateral decisions about entitlement and benefits, regardless of the programs’ fiscal impact or clientele power, and irrespective of whether they fit the incumbents’ ideological preferences.

Policy design dictates the opportunities for retrenchment. Our study showed the mechanism behind successful executive-driven drift: the greater the discretion of the executive, the more room there is for officeholders to quietly curb spending, especially when economic conditions are rapidly deteriorating, and accountability is blurred. Policy design is thus hugely consequential. When facing severe budgetary stress, incumbents can demonstrate commitment to market discipline by quietly freezing existing programs. The concentration of authority allows incumbents to avoid veto points and yields immediate and hidden results. Expediency trumps potential concerns over accountability, which are minimized anyway when policy rules do not require overt revision. In this context, executive-driven drift promotes retrenchment by freezing or downscaling expenditures in the face of mounting social risks.

What are the implications of our findings? First, the policy-focused literature on welfare retrenchment can be enriched by bringing back the role of the concentration of authority and by specifying the conditions under which it leads to successful retrenchment strategies.

Second, the conceptual distinction between executive-driven and opposition-driven drift can be very useful for distinguishing different phenomena currently studied under the same umbrella. Executive-driven drift is a covert strategy used by incumbents to undermine policies, while opposition-driven drift occurs when incumbents are defeated in their efforts to update policies.

Third, our results contribute to a better understanding of the conditions that make some policies more vulnerable to retrenchment. Thus, policymakers interested in protecting programs from future cuts should pay more attention to decision-making rules. More research is needed to refine current theories so that we can fully specify ex ante policies that will be primarily targeted by incumbents.

Fourth, we believe that executive-driven drift is more likely to be an appealing strategy in democracies in peripheral economies, as these are more vulnerable to the risk posed by capital outflows than central economies, although not exclusively. Therefore, our findings may be useful for those studying and formulating public policy in countries that share these characteristics.

We believe that the conceptual distinction we propose can be very helpful for the study of policy drift. However, the issue of endogeneity should also be addressed in the future: is policy design an exogenous source of vulnerability for a given program or is it driven by the vulnerability of the program? To disentangle problems related to reverse causation, future research could focus on identifying the most vulnerable programs in a given context and investigating how they were originally formulated and how program design evolved over time.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper has benefited greatly from the collaboration of Heloisa Fimiani and Rogerio Barbosa, who made important contributions to streamline the argument. The authors would also like to thank comments and suggestions by Adrian Gurza Lavalle, Ana Paula Soares Carvalho, Brodwin Fischer, Candelaria Garay, Daniel Béland, Eduardo Marques, Gabriella Lotta, Jonathan Philips, Luciana de Souza Leão, Matheus Mazzilli Pereira, Renata Bichir, Ursula Peres, Vera Schattan Coelho and Victor Araújo Silva as well as to the organizers of the 8th Red para el Estudio de la Economía Política de América Latina Conference (held in July 2022) and of the Research Commitee 19 of the International Sociological Association (held in August 2021). Funding support from São Paulo state agency for Funding Research by means of the grant 2013/07616-7 and from National Council for Scientific and Technological Development through the grant 308202/2021-0 made this study possible.